Abstract

Compound microbial agents are an important means to optimize soil quality and maintain soil microbial activity. When supplemented with microbial agents, straw returned to a field shows improved degradation efficiency and hence better nutrient release. However, due to the low temperature in the northern winter climate and the complex chemical composition of corn straw, the resultant low decomposition efficiency of straw returning to the field hinders the application of this process. In this study, the low-temperature-degradation microbial agent M44 of corn straw was used as the test material, and the effects of adding the pro-rot microbial agent on straw decomposition, nutrient release, enzyme activity, and the regulation of soil microorganisms were analyzed through an indoor pot straw degradation test. After 16 weeks of degradation under indoor pot conditions, the application of the microbial agent M44 promoted the shedding of the waxy layer on the surface of the straw, the average degradation efficiency of the straw increased by 8.9%, and the average nutrient-release rate of the straw carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium increased by 6.7%, 12.8%, 7.4%, and 9.6%, respectively. The average enzyme activities of soil β-glucosidase (BG), β-xylosidase (BX), laccase (EC), acetyl glucosaminidase (NAG), and leucine aminopeptidase (LAP) increased by9.82, 4.13, 9.46, 2.73, and 5.55 [nmol/(g·h)], respectively, which promoted the degradation of methoxyl carbon and alkoxy carbon, increased the relative content of alkyl carbon, anomeric carbon, aromatic carbon, and carbonyl carbon, and decreased the O-alkyl C/alkyl C value by 2.52; the composition and structure of soil bacterial and fungal communities were significantly changed, and Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Microbacterium, Penicillium, and Gibberella were significantly enriched, which increased the overall microbial activity through the production of degrading enzymes such as cellulase, thereby promoting the rapid degradation of straw. The present results thus provide theoretical support for the efficient decomposition of corn stalks in cold and arid regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Crop straw, which is rich in lignocellulose and contains a large amount of organic matter and nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium, and other nutrients, is a renewable biomass resource1. Returning straw to the field is considered an effective measure to improve soil fertility and increase soil biological activity2,3. However, due to the lignocellulosic composition of straw and cold and dry climatic conditions in some areas, the returned straw does not degrade completely to release the nutrients contained in its natural state4 for use as a fertilizer source for crops in the current season, thereby affecting the sowing quality and becoming unfavorable for the growth of the next crop in rotation5. Especially in the cold and arid regions in the north, the synergistic effect of low temperature and drought in the fall and winter seasons significantly slows down the process of straw degradation, and this bottleneck seriously restricts the ecological benefits of straw return to the field and generates environmental risks.

Microbial-driven processes are the primary force behind lignocellulose degradation and nutrient transformation. Although cellulose-degrading microorganisms are prevalent in agricultural soils, studies have shown that their degradation efficiency varies depending on location and environmental conditions6,7. Previous research has demonstrated that efficient lignocellulose degradation requires the synergistic action of multiple microorganisms, as no single strain is capable of synthesizing all the enzymatic systems necessary to break down cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Moreover, a single bacterial or fungal strain often struggles to independently degrade all straw components, particularly under harsh conditions where its metabolic capacity is limited and its sensitivity to environmental stress is heightened8,9. In contrast, microbial communities can degrade complex substrates synergistically through cooperative metabolism and functional complementarity10,11,12. Recent studies by Jiménez et al.13 and Carlos et al.14 have shown that microbial consortia exhibit superior efficiency and adaptability in lignocellulose degradation.

Studies have shown that natural synthetic flora are an excellent choice for straw degradation due to their stability, synergistic effects, and broad adaptability15. In contrast, single strains have limited functionality, and artificially complex bacteria often lack stability and synergistic effects. Natural synthetic flora, derived from natural environments, exhibit strong resistance to stress, minimal antagonism with indigenous microorganisms, and high efficiency in lignocellulose degradation. Through acclimatization, target microorganisms can be selectively enriched, enhancing their pollutant degradation capabilities and improving the stability of the community structure16. This, in turn, boosts their practicality and persistence in agricultural production.

As a new type of microbial product, a microbial agent has been widely used in recent straw-returning practices. There are several types of functional microorganisms in decay-promoting agents with high metabolic and proliferative abilities and strong environmental adaptability17. Straw returning when combined with microbial agents can improve the utilization efficiency of straw18,19, improve soil enzyme activity20, increase fertilizer and crop yield21,22, and balance the soil microflora23. Wang et al.24 studied different straw-returning methods in combination with a microbial agent and found that the straw-degradation efficiency of returning shallow rotary straw when combined with a microbial agent was better than that of returning no-tillage and subsoiling straw when combined with a microbial agent. Yang et al.25 showed that the combination of returning straw with a decomposing agent and whole-film double-ridge tillage accelerated the straw decomposition and nutrient-release process. However, some studies have demonstrated that the application of microbial agents in the alpine regions did not significantly increase the straw decomposition rate and soil nutrients26,27. Existing microbial agents often exhibit limited efficacy in straw degradation under unfavorable environmental conditions. Therefore, it is essential to investigate functional microbial communities capable of efficiently degrading straw under field conditions, particularly in cold and arid regions.

Building on this, the present study focuses on the natural synthetic flora M44, which was enriched and screened from soil under low-temperature conditions. By evaluating its straw degradation efficiency in simulated cold and arid environments, the study aims to elucidate the mechanisms of microbial interactions. The goal is to provide new insights into the application of local microbial communities for sustainable straw management and soil improvement in extreme environmental conditions.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

The experiment was set up as follows: T1 - sterilized soil + microbial agent, T2 - nonsterilized soil + microbial agent, and T3-nonsterilized soil + no microbial agent. The microbial agent dosage was 0.1 g. The sterilized soil was sterilized by gamma radiation. Each treatment was set up in 35 POTS, and each culture bottle was filled with an appropriate amount of soil. Nylon mesh bags with 4 g of straw segment were washed, dried (at 60℃) to a constant weight, cut to a length of 3–5 cm, and placed in the middle of the soil. Each treatment was combined with ammonium phosphate and urea with the soil water content maintained at 20.0% and incubated in the dark at 15℃; this process was repeated 7 times for each treatment.

Experimental materials

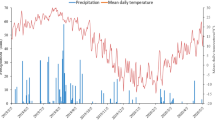

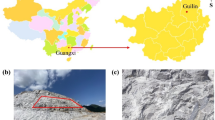

The microbial agent M4428,29 was mainly composed of dominant bacteria such as Pseudomonas, Brevundimonas, and Flavobacterium(It was stored in the microbial strain resource bank of Maize Center, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, numbered IMAU-MCGFM44). The preparation process was as detailed elsewhere16, and the number of viable bacteria was 1 × 109 CFU. The soil and straw tested in the culture bottle were taken from the 5–20 cm soil collected from the experimental field and harvested corn straw (Xianyu 696) sourced from China’s Modern Agriculture Expo Park in Chile, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University. The soil type was sandy loam, and the basic fertility characteristics are shown in Table S1. The lignocellulosic content in the corn stalks is shown in Table S2.

Straw and soil sample collection

The straw samples were removed destructively at week 1 (W1), week 2 (W2), week 4 (W4), week 8 (W8), and week 16 (W16) to determine the relevant indexes of straw degradation, while the soil on the surface of the straw and the background soil around the nylon mesh bag were collected to determine the relevant indexes of microorganisms and soil enzyme activities.

Degradation ratio and nutrient content of the straw

The straw-degradation rate (DSR) was determined by using the weight-difference subtraction method. The degraded straw was dried and crushed, sieved through the 1-mm mesh, and tested for the content of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin as per the method of cellulose analyzer (Model ANKOM220, U.S.A.), followed by the calculation of the change in the degradation rate of lignocellulose. The content of soluble polysaccharides in the straw was determined by using the anthrone colorimetric method. Briefly, a small amount of dry straw sample was coated on a double-sided conductive adhesive. After gold spraying, images were obtained by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at 10-kV acceleration voltage and 400X magnification. The organic carbon content was determined by using the potassium dichromate volumetric method with external heating, the total nitrogen content by H2SO4-H2O2 cooking and distillation method, the total phosphorus content by vanadium-molybdenum-yellow colorimetry, and the total potassium content by the flame photometric method, and the nutrient-release rates were also calculated.

Organic carbon structure of the straw

The chemical structure of the organic carbonization in the straw residues was determined based on CPMAS solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (13 C-NMR) technology using a superconducting high-resolution NMR spectrometer (Bruker Ascend) with a rotating speed of 12 kHz and a preorganic carbonization frequency of 13 C of 500 MHz. The chemical shift distribution of the straw NMR ranged from 0 to 220. As per a previous study30, the NMR map can be divided into six main resonance regions: 0–44 ppm (Alkyl C, Alkyl Carbon), 44–68 ppm (O-CH3/NCH C, Methoxy Carbon), 68–94 ppm (O-Alkyl C, Alkoxy Carbon), 94–113 ppm (O-C-O anomeric C, Anomeric Carbon), 113–162 ppm (Aromatic C, Aromatic Carbon), and 162–220 ppm (Carbonyl C, Carbonyl Carbon).

Soil enzyme activity and microbial diversity

The enzyme activities of β-glucosidase (BG), β-xylosidase (BX), laccase (EC), acetyl glucosidase (NAG), and leucine aminopeptidase (LAP) were determined using a fluorescent microplate enzyme-labeled kit. Microbial biomass carbon (MBC) was determined by fumigation-extraction-volumetric analysis31, while microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN) was determined by fumigation-extraction-Kjelberg nitrogen determination31. The Illumina MiSeq sequencing platform was used to detect the soil microbial community structure and diversity.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 26.0 statistical software was used to conduct the variance analysis of the data, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed based on the Binary_hamming distance, and data analysis of the straw carbon functional groups was performed by MestReNova software. Plot and equation fitting were performed with SigmaPlot 12.5 and Origin 2021, respectively. To reduce the network complexity and improve the calculation accuracy, bacteria and fungi (P < 0.05, r > 0.06, Spearman-related) were screened, and the above screening results were imported into Gephi.0.10, after which bacterial and fungal networks were constructed in soil treated without and with microbial agents.

Results and analysis

Degradation rate of the straw and lignocellulosic components

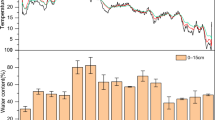

The degradation rate of each of the treatments increased with the continuous culture time showing a “fast-slow” trend during the culture cycle. The fitting of the relationship between the DSR and the degradation time of corn straw was found to be in line with the logarithmic equation (Fig. 1a), indicating that the treatment with the microbial agents (T1, T2) was significantly higher than that without the microbial agent (T3) (P < 0.05). The change of corn straw residue rate with time accords with the double exponential Eqs.32,33 y = CR exp (-KRt) + CS exp (-KSt), where CR is the decomposed component in the fast decomposition stage with decay rate KR (weeks), CS is the decomposed component in the slow decomposition stage with decay rate KS (weeks). T1 = 100.96e− 2.19x + 78.80e − 0.02x, R2 = 0.9992; T2 = 96.38e-2.04x + 78.67e− 0.02x, R2 = 0.9866; T3 = 82.44e− 2.19x + 80.30e− 0.02x, R2 = 0.9990. When compared with the T3 treatment, the fast decay constants of the T1 and T2 treatments were significantly increased by 18.52 and 13.94, respectively. The slow decay constant displayed no significant difference among the T1, T2, and T3 treatments (Fig. 1b).

During the period of rapid straw decomposition in weeks 1st to 2nd, the degradation rates of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin treated by T1 and T2 were significantly higher than those of T3 treatment (P < 0.05) by 7.5%, 2.7%, 15.4%, 11.5%, and 4.8%, 5.0%, respectively (Fig. S1). At the 4th to 16th week, the degradation rates of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin treated by T1 and T2 were significantly higher than those by T3 treatment (P < 0.05), specifically by 6.3%, 5.5%, 9.8%, 12.8%, and 7.1%, 4.5%, respectively. The soluble sugar content of the straw showed the opposite trend; the T1 and T2 treatments showed significantly lower outputs compared to the T3 treatment (P < 0.05), and the straw soluble sugar content of the microbial agents (T1, T2) applied treatments was close to zero at week 16.

At the initial stage of degradation (W1–2), a large number of colonies were attached to the surface of the straw treated with microbial agents M44 (T1 and T2), and the surface structure changed from dense to sparse, with large uneven cracks appearing on the surface, while the waxy layer of the surface structure of the stalks treated with T3 was relatively smooth, regular, flat, and dense (Fig. S2). In the middle and later stages of degradation (W4–16), straw treated with microbial agents M44 (T1 and T2) exhibited uneven pores, exposed fiber structure, and microorganisms embedded in the straw for degradation, while a small number of small pores appeared on the straw surface under the T3 treatment. The overall structure of the straw under the T2 treatment was severely disrupted among the different treatment regimens, and the effect on straw degradation was especially evident.

Nutrient-release rate of the straw

The nutrient-release rates of the straw under each treatment increased with the cultivation time (Fig. 2). During the straw rapid decomposition period (W1–2) and the slow decomposition period of the straw (W4–16), the release rates of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium under the T1 and T2 treatments were significantly higher than those under the T3 treatment (P < 0.05), by 3.5%, 2.2%, 11.6%, 14.3%, 5.2%, 10.5%, 8.9%, 8.7% and 7.9%, 9.7%, 9.5%, 11.8%, 3.4%, 6.5%, 10.6%, 10.5%, respectively. In general, the release efficiency of the straw nutrient elements in W1–2 weeks was higher than that in W4–16, and the nonsterilized soil + combined microbial agent (T2) treatment showed the best results(Fig. 2).

The NMR spectrum

The straw NMR-absorption peaks were identified as detailed elsewhere30. The straw alkoxy carbon (O-alkyl C) and carbonyl carbon (Carbonyl C) were the easily degradable components, while the alkyl carbon (Alkyl C) was difficult to degrade. The relative contents of the easily degradable components O-CH3/NCH Cand O-alkyl C decreased continuously under different treatments, while the degradation efficiency of the straw under the microbial agents M44 (T1, T2) treatment was significantly higher than that under the non-microbial agent (T3) treatment. The results indicated that the addition of agent M44 mainly decomposed cellulose, hemicellulose, and other easily decomposed carbon in straw at the early stage of decomposition. Alkyl C, O-C-O anomeric C, aromatic carbon, and carbonyl C are on the rise, and the latter mainly degrade lignin, tannin, and other difficult-to-decompose carbon (Fig. S3a-c). O-alkyl C/alkyl C was used to indicate the degree of rot of the straw, as shown in Table 1, with no significant difference among the O-alkyl C/alkyl C values between the T1 and T2 treatments (P > 0.05), which was significantly lower than that for the T3 treatment.

The correlation analysis between the DSR and the functional groups (Fig. S4) indicated a significant negative correlation between the DSR and the straw alkyl carbon and methoxy carbon content. In other words, the lower the DSR, the greater the proportion of alkyl carbon and methoxy carbon content. Among them, the correlation coefficients between the proportions of the relative contents of alkyl carbon and methoxy carbon and the DSR were larger under the T2 treatment, suggesting that it was more sensitive to the distribution of the alkyl carbon and methoxy carbon contents under the fungus application (T2) treatment.

The soil enzyme activity

As shown in Fig. 3, soil BG, BX, and NAG activities gradually increased with the process of straw degradation, reaching the peak value in the 8th week, while the LAP activity showed a continuous upward trend, and the enzymatic activity of T1 and T2 treatments was significantly higher than that of T3 treatment. At the early stage of decomposition (W1–2), the EC activity for T1 treatment was significantly higher than that for T2 and T3 treatments, and, from weeks 4–8, the activity was significantly higher for T2 treatment than for T1 and T3 treatments. The comprehensive index of soil enzyme activity showed that the microbial agents (T1, T2) treatment was significantly higher than that of the non-microbial agent (T3) treatment (P < 0.05), which was 4.28 and 10.18-higher, respectively.

Soil microbiota carbon and nitrogen

The soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen content under each treatment exhibited a single-peak curve over the cultivation period (Table S3). At the W8 stage, the soil microbiomass carbon and nitrogen contents were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the microbial agent treatments (T1 and T2) compared to the non- microbial agent treatment (T3). Specifically, soil microbiomass carbon content increased by 509.13 and 231.01 mg·kg⁻¹, while soil microbiomass nitrogen content increased by 114.41 and 27.39 mg·kg⁻¹, respectively. These results indicate that the application of the microbial agent M44 significantly enhanced soil microbiomass carbon and nitrogen content, which favors microbial reproduction and provides essential nutrients for straw degradation. Consequently, this improvement promotes microbial efficiency in degrading straw.

Analysis of the soil microbial alpha diversity and community structure

Significant differences were noted in the Chao index, Ace index, Shannon index, and Simpson index of soil bacteria and fungi under different treatments (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4, Fig. S5). The Chao, Ace, and Shannon indices of the T3 treatment were significantly higher than those of the T1 and T2 treatments (P < 0.05). The Simpson index of the T3 treatment was significantly lower than that of the T1 and T2 treatment (P < 0.05), which were lower by 0.19, 0.11, 0.16, and 0.32, respectively. The Chao and Ace indices under the T2 treatment were significantly higher than those under the T1 treatment, indicating that the application of the microbial agent M44 significantly changed the diversity and richness of the soil bacterial and fungal communities. Based on the composition of the amplicon sequence variant (ASV) of soil bacteria and fungi treated with different treatments, PCoA analysis was performed using the Binary_hamming distance matrix (Fig. 4cf), and the species composition and structure of different degradation stages were significantly clustered under treatments with microbial agents (T1, T2). The absence of microbial agent (T3) was relatively discrete, and the application of the microbial agent was the main driving factor of soil β diversity.

Based on the classification level of bacteria and fungi (Fig. S6a-l), the dominant soil microbial under different treatments were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Ascomycotam, and Basidiomycota. The application of microbial agent M44 can change the composition of the soil indigenous flora, and although T1 and T2 treatments significantly reduce the soil microbial richness and diversity (Fig. 4), the difference analysis results of T2 with microbial agent M44 and T3 without non-microbial agent M44 treatment showed that, during the degradation time, T2 treatment significantly enriched Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Enterococcus, Achromobacter, Massilia, Microbacterium, Penicillium, Caphalotrichum, and Gibberella (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5a-j).

Soil bacterial and fungal network analysis and Zi-Pi module analysis

To further explore the response of indigenous microorganisms to the application of microbial agents under different treatments, a symbiotic network analysis of the soil flora was conducted in this study (Fig. 6). The network connectivity was 18.9% and 16.7% higher in the T3 treatment compared to that in the T1 and T2 treatments, respectively. Modular analysis indicated that the main dominant genera in Modules 1 and 2 were Streptomyces, Microvirga, Enterococcus, Penicillium, Alternaria, and Pseudogymnoascus in the T1 treatment and Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Microbacterium, Penicillium, Gibberella, and Cephalotrichum in the T2 treatment. Streptomyces, Pedobacter, Bacillus, Cladosporium, Alternaria, and Gibberella were the main dominant genera in the T3 treatment. In conclusion, the application of the microbial agent M44 in the treatment could regulate the soil microbial community and the soil microbial synergistic relationship, which significantly increased the abundance of Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Microbacterium, Penicillium, and Gibberella in the soil (Fig. 6 and Fig. S7).

According to Zi (intra-module connectivity) and Pi (inter-module connectivity), most ASVs within these cooccurring networks could be classified as peripherals (Fig. 7). The key bacterial dominant species between the different treatments were defined as 1 Modulehubs and 6 Connectors, wherein Proteobacteria was the main module hub and ASV135 of Proteobacteria was Pantoea. The connectors of bacteria included Actinobacteriota, Adhaeribacter, and Proteobacteria. The fungal bacterial dominant species connectors include Basidiomycota and Ascomycota. Meanwhile, no network hubs were detected in bacteria and fungi in different treatments. These results proved that different application treatments mainly induced changes in the core flora of Proteobacteria (Pantoea), Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, and Ascomycota.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) of the soil microbial network modules and indicators related to straw degradation

To quantify the causal relationship between the soil microbial network modularity and environmental factors, SEM was used, which showed that the application of the microbial agent M44 (T2 treatment) could significantly increase the negative correlation effects of the soil bacterial network Module 1 on β-glucosidase, LAP, laccase, and β-glucosidase on the nitrogen-release rate and phosphorus-release rate, with a positive correlation effect of laccase on the nitrogen-release rate (Fig. 8). Moreover, the explained DSR was higher than that of the T3 treatment, which was 0.054, indicating that the application of the microbial agent M44 could increase the explained rate of the maize stover-related indexes on the explanation rate of the stover-degradation rate (Fig. 8b). This suggests that the application of the microbial agent M44 could improve the soil microbial activity by altering microbial interactions, reducing competition, or promoting cooperative relationships between certain bacterial groups, which, in turn, could improve the efficiency of straw degradation (Fig. 8, Fig. S8).

Structural equation modeling (SEM) of soil bacterial network modules and indicators related to straw degradation. (1) The arrows indicate the standardized path coefficients (SPCs); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (2) Red color represents positive correlation, blue color represents negative correlation, solid lines represent significance, black dashed lines represent non-significance, and the thickness of the lines indicates the size of the path coefficients. (3) DSR: Straw-degradation rate; Module 1: Soil bacterial network module 1; Module 2: Soil bacterial network module 2; BG: β-glucosidase; LAP: Leucine aminopeptidase; EC: Laccase; C: Straw carbon-release rate; N: Straw nitrogen-release rate; P: Straw phosphorus-release rate.

Correlational analysis between the DSR and environmental factors

Correlational analysis between soil microbial diversity and environmental factors (Fig. 9) revealed that DCR, DBCR, C, P, LAP, Anomeric-C, Aromatic-C, and MBC were highly significantly and positively correlated with the microbial agent (T2) treatment and that C, BG, BX, LAP, Alkyl-C, and Methoxyl-C were positively correlated with the fungal community composition. Moreover, DSR, DCR, DBCR, DLR, C, P, BX, LAP, Allkyl-C, Anomeric-C, and Carbonyl-C were highly significantly and positively correlated with the bacterial community composition in the no-microbial agent (T3) treatment, and DCR, DBCR, DLR, P, BX, LAP, NAG, O-allkyl-C, Anomeric-C, and Carbonyl-C were highly significantly and positively correlated with the fungal community composition. In conclusion, it was shown that soil MBC, straw alkyl carbon (Alkyl-C), methoxyl carbon (Methoxyl-C), and fast-acting nitrogen and phosphorus were the main factors driving changes in the microbial communities. Thus, the application of microbial agents not only directly affected the composition of microbial communities but also indirectly enhanced microbial interactions and functional efficiency by modifying the soil environment.

Correlational analysis of soil bacteria, fungi, and straw degradation-related indexes. DSR: Straw-degradation rate; DCR: Cellulose-degradation ratio; DHR: Hemicellulose-degradation ratio; DLR: Lignin-degradation ratio; LAP: Leucine aminopeptidase; BX: β-xylosidase; BG: β-glucosidase; NAG: Acetylglucosaminidase; EC: Laccase.

Discussion and conclusion

Decomposition and nutrient release of returning straw are the keys to soil fertility. Straw return to the field provides a sufficient carbon source for soil microorganisms, promotes the growth and reproduction of microorganisms, and improves soil biological activity. The degradation of straw and the transformation of organic matter are mainly controlled by microorganisms. Straw microbial degradation is a new way to effectively promote the crop straw decomposition process, and the stability of the microbial flora is an important prerequisite to ensure its effectiveness.

In this study, we demonstrated that the microbial agent M44 significantly increased the maize straw degradation rate under low-temperature conditions, showing a 12.2% higher degradation rate compared to the control group. This indicates that microbial agent M44 possesses high adaptability and degradation capacity in cold environments. The major functional bacteria in the microbial agent M44, such as Pseudomonas and Microbacterium, secrete enzymes involved in cellulose degradation, thereby significantly promoting cellulose hydrolysis34,35,36. High-throughput sequencing results revealed that the application of the microbial agent M44 enriched core microbial communities with lignocellulose degradation capabilities and accelerated the decomposition of easily degradable carbon components, in line with previous studies37. In this study, microbial co-occurrence networks and Zi-Pi analysis identified Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, and Penicillium as core species in the degradation modules, collectively forming an efficient synergistic degradation system. The abundance of these core species was significantly correlated with key enzyme activities and straw degradation indicators, confirming the positive effect of optimized network structures on degradation efficiency. Furthermore, the application of the microbial agent M44 significantly increased soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN) content, thereby enhancing the soil carbon pool38. It also accelerated straw decomposition through a multi-layered mechanism, including microscopic structural damage, enhanced enzymatic activity, and community reconstruction. Although the application of the microbial agent M44 reduced soil microbial diversity and richness, it enriched dominant degrading microbial groups such as Proteobacteria and Enterococcus. Under microbial agent-driven conditions, certain microbes exhibited selective advantages, consistent with previous research findings39.

In this experiment, under indoor sealed conditions, the microbial agent M44 significantly enhanced straw degradation efficiency by regulating the soil microbial community structure and optimizing microbial interactions. SEM analysis revealed that the microbial agent M44 promoted negative correlations between microbial network module 1 and enzymes involved in nitrogen and phosphorus release, while also enhancing microbial synergy. Network analysis further showed that the microbial agent M44 improved the connectivity of the microbial community by increasing the abundance of beneficial genera such as Pseudomonas and Stenotrophomonas. Correlation analysis indicated that the microbial agent M44 indirectly promoted microbial activity and straw degradation by altering the soil environment, including the availability of nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic carbon. In conclusion, the microbial agent M44 significantly enhanced straw degradation efficiency under indoor sealed conditions by modulating microbial community composition, strengthening synergistic effects, and optimizing the soil environment.

Unlike previous studies, which have primarily focused on temperate and humid environments, this study is the first to validate the degradation effect of microbial consortia under cold and arid conditions. The results demonstrate that, even under such restrictive conditions, the microbial agent M44 significantly promotes the degradation of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, overcoming the degradation bottleneck of straw in cold and arid regions, with promising application prospects. However, it is important to note that this experiment was conducted under controlled indoor conditions, which did not account for the complex environmental factors present in field conditions. Therefore, future field trials are necessary to evaluate the environmental adaptability, sustained degradation capacity, and potential impact on crop growth.

In summary, the microbial agent M44 promotes straw degradation by regulating microbial community structure, enhancing enzymatic activity, and reshaping the abundance and interactions of key genera in modules 1 and 2 (such as Streptomyces, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, and Gibberella). This process leads to the decomposition of easily degradable components (O-alkyl C, Carbonyl C) and the accumulation of more resistant components, contributing to the establishment of a more stable and efficient degradation system40. The study highlights the potential application of the microbial agent M44 in regulating the straw decomposition process in restrictive environments, such as cold and arid conditions. This research provides theoretical support and practical pathways for rapid straw return and sustainable soil management in cold and arid regions, demonstrating the potential of microbial community activity to drive straw decomposition under unfavorable environmental conditions.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s). The microbial raw sequence data were deposited in the NCBI and are available under accession numbers PRJNA 1205916.

References

Çağrı, A., Orhan, I. & Bahar, I. Crop-based composting of lignocellulosic digestates: focus on bacterial and fungal diversity. Bioresour. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121549 (2019). 288,121549.

Jin, J. X., Li, Y. & Cai, H. G. Response of soil organic carbon to straw return in farmland soil in china: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manage. 359, 121051–121051. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2024.121051.( (2024).

Yang, H. S. et al. Long-term ditch-buried straw return alters soil water potential, temperature, and microbial communities in a rice-wheat rotation system. Soil Tillage. Res. 163, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2016.05.003 (2016).

Qin, X. Y., Huang, W. Y. & Li, Q. L. Lignocellulose biodegradation to humic substances in cow manure-straw composting: characterization of dissolved organic matter and microbial community succession. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.137758 (2024).

Zhang, H. P. et al. Combining conservation tillage with nitrogen fertilization promotes maize straw decomposition by regulating soil microbial community and enzyme activities. Pedosphere 34, 4:783–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PEDSPH.2023.05.005 (2024).

López-Mondéjar, R., Zühlke, D., Becher, D., Riedel, K. & Baldrian, P. Cellulose and hemicellulose decomposition by forest soil bacteria proceeds by the action of structurally variable enzymatic systems. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25279.( (2016). 6,1:25279.

Bao, Y. Y. et al. Important ecophysiological roles of non-dominant Actinobacteria in plant residue decomposition, especially in less fertile soils. Microbiome https://doi.org/10.1186/S40168-021-01032-X (2021).

Kausar, H., Ismail, M. R., Saud, H. M., Othman, R. & Habib, S. Use of lignocellulolytic microbial consortium and pH amendment on composting efficacy of rice straw. Compost Sci. Utilization. 21 (3–4), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/1065657x.2013.842131.( (2013).

Cle´mence, F., Enora, F., Camille, T. & Anne, S. Scalable and exhaustive screening of metabolic functions carried out by microbial consortia. Bioinformatics 34 (17), i934. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty588 (2018).

Qiao, C. et al. Key extracellular enzymes triggered high-efficiency composting associated with bacterial community succession. Bioresour. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121576 (2019).

Kondo, M. Foraging adaptation and the relationship between food-web complexity and stability. Science 299 (5611), 1388–1391. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1079154 (2003).

Jiang, G. F. et al. Construction of a composite fungal system for degrading corn Stover and evaluation of its degradation effect. J. Plant. Nutr. Fertilizer. 27 (02), 284–292. https://doi.org/10.11674/zwyf.20363.( (2021).

Jiménez, D. J., Chaves-Moreno, D. & Elsas, J. D. V. Unveiling the metabolic potential of two soil-derived microbial consortia selected on wheat straw. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13845 (2015).

Maruthamuthu, M., Jiménez, D. J., Stevens, P. A. & Elsas, J. D. V. A multi-substrate approach for functional metagenomics-based screening for (hemi)cellulases in two wheat straw-degrading microbial consortia unveils novel thermoalkaliphilic enzymes. BMC Genom. 17, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-2404-0 (2016).

Wang, B. Study on the mechanism of composite microbial agents accelerating the degradation of lignocellulose in quasi-aerobic landfills (Master’s thesis). Southwest Jiaotong University. (2022). https://doi.org/10.27414/d.cnki.gxnju.2022.003516.(

Zhang, X. Screening of low-temperature degradation composite bacterial lineages of corn Stover in cold and arid areas and the degradation mechanism and application effect of M44. Inner Mongolia Agricultural Univ. https://doi.org/10.27229/d.cnki.gnmnu.2022.000058 (2022).

Gaind, S. & Nain, L. Chemical and biological properties of wheat soil in response to paddy straw in crop oration and its biodegradation by fungal inoculants(microbial agent). Biodegradation 18 (4), 495–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-006-9082-6 (2007).

Li, M. H. et al. High performance bacteria anchored by nanoclay to boost straw degradation. Materials 12 (7), 1148–1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12071148 (2019).

Mian, Y. M., Li, R., Hou, X. Q., Li, P. F. & Wang, X. N. Effects of straw return with rotting agent on sandy soil properties and growth of drip-irrigated corn. J. Nuclear Agric. 34 (10), 2343–2351. https://doi.org/10.11869/j.issn.100-8551.2020.10.2343.( (2020).

Wen, Y. T. et al. Enhancing rice ecological production: synergistic effects of wheat-straw decomposition and microbial agents on soil health and yield. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1368184–1368184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1368184 (2024).

Fan, Z. W. et al. Study on the application effect of rotting fungicides on corn Stover under different methods of field return. Corn. Sci. 29 (02), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.13597/j.cnki.maize.science.20210217.( (2021).

Thilagar, G., Bagyaraj, D. J. & Rao, M. S. Selected microbial consortia developed for chilly reduces application of chemical fertilizers by 50% under field conditions. Sci. Hort. 198, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2015.11.021 (2016).

Yang, H. S. et al. Response of soil bacterial diversity of different textures to corn Stover return with rotting agent. Soil. Bull. 50 (06), 1352–1360. https://doi.org/10.19336/j.cnki.trtb.2019.06.13.( (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Effects of different returning method combined with decomposer on decomposition of organic components of straw and soil fertility. Scientifc Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-021-95015-5 (2021). 11,15495.

Yang, E. K., He, B. L., Zhang, L. G., Zhang, G. P. & Gao, Y. P. An approach to improve soil quality: a case study of straw incorporation with a decomposer under full film-mulched ridge-furrow tillage on the semiarid loess plateau, China. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 20, 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-019-00106-y.( (2020).

Yang, X. R. et al. Integrating and analyzing the effects of straw rotting agent application on straw decomposition and crop yield in Chinese farmland. Chin. Agricultural Sci. 53 (07), 1359–1367. https://doi.org/10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2020.07.006.( (2020).

Li, C. J., Sun, T. & Zhang, X. Y. Effects of straw rotting agent on degradation rate of corn Stover and soil physicochemical properties in cold land. North. China J. Agric. 30(S1),507–510. https://doi.org/10.7668/hbnxb.2015.S1.091.(2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Community succession and functional prediction of microbial consortium with straw degradation during subculture at low temperature. Scientific Reports. 12,20163. (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Community succession and straw degradation characteristics using a microbial decomposer at low temperature. PLoS ONE. 17 (7), e0270162. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270162 (2022).

Han, Y. Research on decay characteristics of corn Stover and its soil modification effect in black soil area. Chin. Acad. Agricultural Sci. https://doi.org/10.27630/d.cnki.gznky.2019.000054.( (2019).

Chen, S. T., Zhang, T. T. & Wang, J. Warming But Not Straw Application Increased Microbial Biomass Carbon and Microbial Biomass Carbon/Nitrogen: Importance of Soil Moisture. Water Air Soil Pollut. 232(2)53. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11270-021-05029-Y. (2021).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Microbial keystone taxa drive succession of plant residue chemistry. ISME J. 17 (5), 748–757. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41396-023-01384-2 (2023).

Strukelj, M., Brais, S., Mazerolle, M. J., Paré, D. & Drapeau, P. Decomposition patterns of foliar litter and Deadwood in managed and unmanaged stands: A 13-Year experiment in boreal mixedwoods. Ecosystems 21 (1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-017-0135-y (2018).

Long, M. et al. Temperature matters more than fertilization for straw decomposition in the soil of greenhouse vegetable field. Agronomy 14 (2), 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/AGRONOMY14020233.( (2024).

Pei, Y. N. et al. Effects of straw return with rot-promoting fungicides on soil aggregates and their nutrients. J. Appl. Ecol. 34 (12), 3357–3363. https://doi.org/10.13287/J.1001-9332.202312.018.( (2023).

Wang, X. Y. From residue to resource: A physicochemical and Microbiological analysis of soil microbial communities through film Mulch-Enhanced rice straw return strategies. Agronomy 14 (5), 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/AGRONOMY14051001.( (2024).

Rifai, S. W., Markewitz, D. & Borders, B. E. Twenty years of intensive fertilization and competing vegetation suppression in loblolly pine plantations: impacts on soil C, N, and microbial biomass. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42 (5), 713–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.01.004 (2010).

Houssoukpèvi, A. I. et al. Differences in soil biological activity and soil organic matter status only in the topsoil of ferralsols under five land uses (Allada, Benin). Geoderma Reg. 39, e00865–e00865. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GEODRS.2024.E00865 (2024).

Nie, Y. M. et al. [Effect of High-volume straw returning and applying Bacillus on bacterial community and fertility of desertification soil]. Huan Jing Ke xue = huanjing Kexue. 44(9)5176–5185 (2023). https://doi.org/10.13227/J.HJKX.202210252

Wang, J. H. et al. Synergistic analysis of lignin degrading bacterial consortium and its application in rice straw fiber film. Sci. Total Environ. 927, 172386–172386. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2024.172386.( (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the following projects: National Key Research and Development Program (2023YFD1501500); National Natural Science Foundation of China (32260532); Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation of China (2024MS03052); Youth Science and Technology Talent Support Program of Colleges and Universities in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (NJYT25021);Research Project of Carbon Peak Carbon Neutralization in Universities of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (STZX202304); Basic Research Funds for Universities directly under the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (BR22-11-07);Key Laboratory of Crop Cultivation and Genetic Improvement, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (2023KYPT0023);National Technical System for Maize Industry (CARS-02-74).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WLJ wrote the first and revised drafts. WLJ and ZWS performed the primary data analysis. QGE conceived project idea, and design, provided suggestions for revising the paper. LRZ, JHR recorded and measured the test data. YXF, GJL, HSP made suggestions for revising the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Zhao, W., Liu, R. et al. Study on the effect of microbial agent M44 on straw decay promoting in cold soils. Sci Rep 15, 22539 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05817-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05817-0