Abstract

The effect of oil shale expansion and the addition of FeCl3 on its pyrolysis behavior was studied by hydrothermal pyrolysis experiments of cylindrical oil shale at 350 °C. The expansion of oil shale promotes the development of pores and fractures, which leads to the drastic pyrolysis of kerogen and the discharge of pyrolysis products. Besides, when the radial swelling increment of the oil shale is 33% of the free expansion, the pyrolysis reaction is basically guaranteed. When the radial expansion increment of the oil shale is greater than 33% of the free expansion amount, FeCl3 can effectively improve the yield of expelled oil by promoting the fracture of polycyclic structure and C-O bond in the kerogen, accelerating the migration of bitumen and urging the water to participate in the reaction. In addition, when the radial swelling increment of oil shale increases, the content of small molecule compounds in the expelled oil is reduced. These findings demonstrated that hydraulic fracturing of oil shale reservoirs and adding FeCl3 can effectively guarantee the success and economy of in-situ oil shale mining.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The strong demand for energy in modern industry and the increasing consumption of traditional fossil fuels have forced the world to invest in alternative energy research1,2. Oil shale, with its enormous reserves, has drawn extensive attention from researchers and is considered to be a prospective alternative energy sources for petroleum3,4. Kerogen is distributed in the inorganic mineral skeleton and can be converted to oil and gas5,6. At present, oil shale is developed and utilized mainly by surface retorting7,8. However, in-situ conversion is more economical and environmentally friendly, and has the potential to become a transformative technology to change the world’s energy landscape. Therefore, how to realize the underground in-situ heating-pyrolyzing of oil shale has become a continuous research hotspot. The heating methods mainly include: conduction heating, convection heating, radiation heating, and combustion heating. Currently, a variety of oil shale in-situ conversion technology methods have been developed, but in general, these technologies are still in the research and development stage9,10. The convection heating technology has the characteristics of fast heating speed, high product recovery yield, and environmental friendliness, and is suitable for oil shale with deep burial and low oil content11. The overall idea of convection heating is to drill a single well or multiple wells into the oil shale layer from the ground, perform hydraulic fracturing on the oil shale layer to form products output channels, and introduce a high-temperature heat carrier to heat the oil shale layer, so that kerogen pyrolysis produces oil and gas and carries them the ground.

Subcritical water is an ideal heat transfer, mass transfer, and reaction medium, its high pressure has a fracturing effect on oil shale layers, it can crack oil shale at about 300 °C, and has a good displacement effect on the pyrolysis products12,13. Therefore, subcritical water is recommended by many researchers for oil shale mining14,15.

Subcritical water is widely used for the pyrolysis of heavy oil, coal, biomass, and organic contaminant16,17,18. Similarly, the effects of various subcritical water conditions on oil shale pyrolysis behavior and product distribution have also been well studied19,20,21. The main control factors for oil shale pyrolysis in subcritical water are the pyrolysis temperature and time. In general, the higher the temperature, the longer the time, and the higher the shale oil yield. However, too high a temperature and too long a time will lead to intensification of the secondary pyrolysis reaction of shale oil and reduce the yield of shale oil. Compared with anhydrous pyrolysis, the temperature required for oil shale pyrolysis in subcritical water is lower, however, the time required is longer22. In addition, the oil shale pyrolysis reaction is also affected by the oil shale-water mass ratio, oil shale particle size, pressure, and other factors23,24.

Theoretically, the increase of oil shale particle size leads to the extension of heat and mass transfer channels, which is not conducive to oil shale pyrolysis. However, the experimental results show that oil shale under the condition of free expansion, the increase of its particle size only leads to a slightly lower oil yield in the early stage of pyrolysis. With the extension of the pyrolysis time, the effect of oil shale particle size on shale oil yield is negligible. This is due to the high pressure of subcritical water will cause bulk oil shale to expand and crack into fragments25. This has led to subsequent studies no longer paying attention to the effect of oil shale size on its pyrolysis behavior. However, when oil shale is heated in-situ, the expansion and fracture of oil shale are hindered by the existence of overlying strata, and the development of pores and fractures in oil shale is poor. In the pilot test project of oil shale in-situ conversion in Jilin Province, Jilin University found that when the oil shale layer after fracturing is heated for the first time, due to the expansion of oil shale, the fractures between the mining well and the production well are closed, and the heat carrier is difficult to inject underground. This means that it is necessary to study the pyrolysis behavior of bulk oil shale under restrained conditions for guiding the conversion of underground oil shale. At present, the research on the effect of oil shale expansion on its hydrothermal pyrolysis is still in the blank stage.

Our previous work shows that when cylindrical oil shale is subjected to hydrothermal pyrolysis under rigid restraint conditions, the time required is multiplied and the development of pores and fractures is also poor26. However, in the process of oil shale in-situ conversion, due to the differences in geological conditions and hydraulic fracturing effects, the swelling increment of oil shale varies. Therefore, it is of great significance to reveal the influence of oil shale swelling increment on its hydrothermal pyrolysis behavior and product characteristics. Meanwhile, considering that the pyrolysis rate of oil shale is greatly reduced under restraint conditions, efficient, cheap, and environmentally friendly FeCl3 is selected to promote the hydrothermal pyrolysis reaction.

In this work, cylindrical Huadian oil shale cores were employed to subcritical water pyrolysis experiments to explore the effects of core swelling increment and FeCl3 on their pyrolysis behavior. The mechanism was revealed by pyrolysis products’ yields and compositions. It is hoped that this study can provide some guidance value for oil shale in-situ conversion.

Materials and methods

Materials

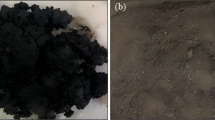

The oil shale samples were collected from the Dachengzi mine located in Huadian City, Jilin Province of China. The basic properties of the oil shale samples are listed in Table 1. Before extraction experiments, the bulk oil shale samples were cut into regular cylinders with a diameter of 25 mm and a height of 30 mm. The mass of each cylindrical oil shale sample was approximately 20.5 g, and the bedding was perpendicular to the bottom of the cylinder. The radial swelling increment of cylindrical oil shale was controlled to be 0, 1.5, 3, and 9 mm (free expansion) by customized stainless-steel fixtures. The cylindrical oil shale sample and the stainless-steel fixture are shown in Fig. 1. Commercially available FeCl3·4 H2O was dissolved in deionized water to prepare a solution of 0.08 mol/L. The reason for choosing this concentration is that our previous research results have proved that 0.08 mol/L FeCl3 is the optimal concentration for the catalytic effect of hydrothermal pyrolysis of oil shale under free expansion conditions27.

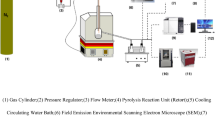

Pyrolysis experiment

A 0.5 L stainless steel autoclave was used for the oil shale hydrothermal pyrolysis experiment. Two cylindrical oil shale (fixed with stainless-steel fixtures, respectively) and 250 ml of deionized water or 0.08 mol/L of FeCl3 aqueous solution were used in each experiment. After the reactor was sealed, injected 3 MPa of N2 for several times to displace the air in the headspace of the reactor. According to our existing research results, the final heating temperature was set to 350 °C (the pressure is approximately 16.3 MPa), and the holding time was 20 h. The pyrolysis products were collected in sequence after the autoclave was cooled to room temperature.

Treatment of pyrolysis products

The expelled oil was separated into four components by column chromatography. Firstly, 0.100 g of the expelled oil was dissolved in 50 ml of n-hexane and then filtered. The residue was asphaltene, and the filtrate was injected into the chromatography column loaded with alumina and silica gel. Then, the saturated hydrocarbon, aromatic hydrocarbon, and resin were eluted with n-hexane, n-hexane/dichloromethane (volume ratio 1:2), and benzene/methanol (volume ratio 1:1), respectively. Finally, the four components were dried to a constant weight. Expelled oil was dissolved by toluene, and the toluene soluble matter was obtained for GC–MS analysis. For each dissolution, the amount of expelled oil and toluene was 0.80 g and 60 ml, respectively, and the temperature and time was 90 °C and 12 h, respectively. Bitumen was extracted from the oil shale residue using dichloromethane in a Soxhlet apparatus. For each extraction, the amount of oil shale residue and dichloromethane was 8.000 g and 110 ml, respectively, and the temperature and time was 55 °C and 12 h, respectively. The mass of oil shale residue decrement is the mass of bitumen28.

The calculation formula of product yield is as follows:

where mo is the weight of the original oil shale (g); moil is the weight of expelled oil(g); mres is the weight of oil shale residue(g); mres1 is the weight of oil shale residue before Soxhlet extraction (approximately 8.000 g); mres2 is the weight of oil shale residue after Soxhlet extraction(g).

Composition analysis of pyrolysis products

The compositions of bitumen and expelled oil were obtained using an Agilent 7890A-5975N gas chromatograph mass spectrometer (GC–MS). Gas composition was analyzed by an Agilent 7890B gas chromatography (GC). The instrument parameters were described previously14,29.

Results and discussion

Product yield of hydrothermal pyrolysis experiment

As shown in Fig. 2, with the increase of the radial swelling increment, the yield of expelled oil increases gradually, and the yield of bitumen decreases gradually, while the sum of the two increases. This indicates that the increase of oil shale expansion could not only promote kerogen pyrolysis, but also facilitate bitumen discharge, thus greatly improving the production of expelled oil. The internal pores and fractures develop smoothly with the expansion of the oil shale, which promotes heat and mass transfer30. For the non-catalytic pyrolysis experiment, when the radial swelling increment of the oil shale is 0 cm, the yield of expelled oil is only 5.3 ± 0.26%, this is much lower than the oil yield of oil shale under free expansion conditions in similar studies25,27; when the radial swelling increment of the oil shale is 0.30 cm (33% of the free expansion), the yield of expelled oil is approach to that in free expansion state. This implies that when the radial swelling increment of oil shale is 0.30 cm, the heat and mass transfer requirements can be satisfied basically. This shows that it is defective to predict the oil yield by the experimental results of oil shale under the condition of free expansion when carrying out the in-situ mining project of oil shale. The expandable amount of oil shale should be reasonably calculated according to the hydraulic fracturing data, and then the pyrolysis rate and oil yield of oil shale can be more accurately predicted.

When the radial swelling increment of oil shale is less than 0.15 cm, the addition of FeCl3 has little effect on the yield of expelled oil, but enhances the yield of bitumen. This is because the radial swelling increment of oil shale is small, only a small amount of subcritical water can penetrate the oil shale, that is, only a small amount of Fe3+ can enter the oil shale with subcritical water. This part of Fe3+ effectively promotes the decomposition of kerogen to produce bitumen, while the generated bitumen is trapped in the oil shale matrix because the fissure has not yet been effectively expanded. When the radial swelling increment of oil shale is 0.30 cm, adding FeCl3 increases the yield of expelled oil by 48.30%; when the radial swelling increment of oil shale is 0.90 cm, adding FeCl3 increases the yield of expelled oil by 65.59%. Similarly, this indicates that only when the radial swelling increment of oil shale is ≥ 0.30 cm (33% of the free expansion), the catalytic activities of FeCl3 can manifest significantly. In addition, it could also be seen that FeCl3 has a significant catalytic effect on the hydrothermal pyrolysis of oil shale. After adding FeCl3, the expelled oil yield reaches 91.4% of Fischer assay analysis (16.85 wt%) in only 20 h. When no catalyst is added, it took 70 h to obtain a similar expelled oil yield.

The above discussion indicates that hydraulic fracturing of oil shale reservoir to produce additional fractures before in-situ mining is necessary. Besides, adding FeCl3 could greatly enhance the efficiency of shale oil production, thereby improving the feasibility and economy of in-situ mining project.

Expelled oil composition

The SARA-analysis of expelled oil is exhibited in Fig. 3. The standard deviation of the relative percentage of the four components is between 0.40% and 0.88%. The relative content of the micromolecular compounds (Sa and Ar) gradually decrease with the radial swelling increment of oil shale, while the relative content of the macromolecular compounds (Re and As) gradually increases. When the expansion of oil shale is limited, the pores and fractures develop hardly, which makes it difficult for the macromolecular compounds (Re and As) to migrate out27, Hu also found that asphaltene is difficult to discharge due to its high viscosity31. Turakhanov et al. considered that the secondary pyrolysis in a short time is not enough to crack these macromolecular compounds into small molecules, and prolonging the pyrolysis time can improve the quality of the product32. The secondary pyrolysis of macromolecular compounds requires sufficient heat to destroy chemical bonds, and the active free H in subcritical water can also quickly combine with the unstable groups produced by the secondary pyrolysis to avoid their mutual polymerization. On the contrary, when the radial swelling increment of oil shale increases, macromolecular compounds can be discharged smoothly, and the content of macromolecular compounds in expelled oil will increase. Most of the Fe3+ is adsorbed by clay minerals after entering the oil shale matrix, so it has little catalytic effect on expelled oil.

The relative contents of the various substances in expelled oil are calculated based on their peak areas in GC–MS chromatograms, and the results are shown in Fig. 4. With radial swelling increases, the relative content of n-alkanes increases, while the content of oxygenated compounds (n-alkane-2-ones and n-alkanoic acids) decreases. As the expansion of oil shale increases, the degree of kerogen pyrolysis increases, and the oxygen-containing groups in kerogen mainly break off in the early stage33,34. This is because the bond energy of the C–O bond is small, and it is first broken under the action of subcritical water, and can greatly destroy the stability of the kerogen structure. In addition, decarbonylation and decarboxylation reactions also lead to the conversion of oxygenated compounds into n-alkanes. After adding FeCl3, n-alkanes content increases more obviously, which also indicates that FeCl3 promotes the cracking of kerogen and oxygenated compounds. It can be observed that the relative content of aromatics increases after adding FeCl3. In general, the aromatic groups in kerogen are relatively stable and difficult to crack in subcritical water, while FeCl3 promotes the cracking of these multi-aromatic ring structures to a certain extent. This is because Fe3+ has a strong electron-withdrawing ability, which can effectively promote the breakage of heteroatom bonds and the bridge bonds in aromatic groups (electron pair offset), and the free radicals produced by the breakage can be combined with H in water. This reflects the synergistic mechanism of subcritical water and Fe3+. n-Alkenes are not stable in subcritical water and react with water to form n-alkanes and ketones, so n-alkenes are almost not detected in expelled oil 35. It is worth mentioning that the oil obtained from oil shale under non-sub critical water conditions contains a large number of n-alkenes, which also indicates that water will participate in the conversion reaction of n-alkenes29,36.

The n-alkanes are divided into three parts based on their carbon atoms number: C10-C19, C20-C27, and C28-C35. It can be seen from Fig. 5 that with or without FeCl3, with the rise of the radial swelling increment, the relative percentage of C10-C19 n-alkanes shows an overall decreasing trend, while the relative percentage of C20-C27 and C28-C35 n-alkanes shows an overall increasing trend. This is because when the expansion of oil shale is small, the small molecule n-alkanes are more easily discharged. When the expansion of oil shale increases, macromolecular n-alkanes can also be more convenient to release, this has increased the content of macromolecular n-alkanes in expelled oil. The increase of porosity can promote the migration of products, which is consistent with Wang’s research results 37. The C–C bond is relatively stable, and its destruction depends more on the long-term hydrothermal environment, while the contribution of FeCl3 is smaller.

Bitumen composition

The dominating component of the bitumen is n-alkanes, in addition to a few n-alkane-2-ones, cycloalkanes, and isoprenoids. The number of carbon atoms of n-alkanes is also marked. The number of carbon atoms of n-alkanes in residual bitumen is distributed between C15 and C34, and low molecular weight n-alkanes are less compared to expelled oil. With the expansion of oil shale increases, the relative content of n-alkanes increases slightly. This is similar to the n-alkanes content variation in expelled oil.

ΣnC21−/ΣnC22+ represents the ratio of n-alkanes with carbon atoms less than or equal to 21 to n-alkanes with carbon atoms greater than or equal to 2238. Figure 6 shows the variation of ΣnC21−/ΣnC22+ index of bitumen. With the enhancement of the radial swelling increment, ΣnC21−/ΣnC22+ index gradually decreases. This is because when the expansion of oil shale was small, the thermal cracking of kerogen in block oil shale is not sufficient, and branched alkanes fall off to produce small molecular n-alkanes. As the expansion of oil shale, the long-chain alkane groups in kerogen gradually crack, resulting in more macromolecular n-alkanes.

Gas composition

The composition and relative content of gaseous products obtained from oil shale pyrolysis experiments under different expansion conditions are shown in Table 2. After adding FeCl3, the relative contents of CO2, H2S, and ∑C1-C5 gradually increase with the swelling increment of oil shale, while the relative content of H2 dramatically decreases. CO2, as the most abundant gas, originates mainly from the pyrolysis of carboxyl groups in kerogen and the decomposition of carbonate minerals, and FeCl3 has high catalytic activity for both reactions. H2S will react with Fe3+ to form pyrrhotite (Fe1−xS) during its escape process39. When the expansion of oil shale increases, the H2S that escapes quickly is difficult to fully react. In addition, both kerogen pyrolysis and bitumen products’ secondary cracking generate organic gas40,41,42, which also leads to an enhancement in the content of ∑C1–C5. When the radial swelling increment is small, the content of H2 is extremely high, which indicates that Fe3+ can effectively promote the production of H2 from water. Meanwhile, H2 also participates in the pyrolysis reaction of kerogen. When the expansion increases, the kerogen pyrolysis intensifies, resulting in the quick consumption of H2. When FeCl3 is not added, the relative contents of CO2 and ∑C1–C5 have no obvious trend, but fluctuate within a certain range. This is because as the expansion of oil shale increases, the pyrolysis reaction of organic matter and carbonate minerals intensifies synchronously.

Conclusion

Hydrothermal pyrolysis of cylindrical Huadian oil shale with different radial swelling increments is carried at 350 °C in the presence/absence of FeCl3. Oil shale expansion could promote the development of pores and fractures, which facilitates kerogen pyrolysis and bitumen discharge. Meanwhile, when the radial swelling increment is 33% of the free expansion, the requirements for heat and mass transfer can be satisfied basically. Besides, FeCl3 exhibits a significant catalytic effect on oil shale pyrolysis, Fe3+ can effectively promote the breakage of heteroatom bonds and the bridge bonds between aromatic rings in kerogen to produce free radicals, which are quickly stabilized by active H in subcritical water. When the radial swelling increment of oil shale increases, the relative content of the micromolecular compounds in expelled oil decreases, and C10–C19 n-alkanes content also shows an overall decreasing trend. These because macromolecular compounds can be smoothly discharged when the expansion of oil shale increases. What’s more, as the increase of the radial swelling increment, ΣnC21−/ΣnC22+ index gradually decreases. Fe3+ will react with H2S to form pyrrhotite (Fe1−xS), and can effectively promote the production of H2 from water. Meanwhile, H2 is consumed while participating in kerogen pyrolysis. The research demonstrates that FeCl3 has a wonderful promotion on the hydrothermal pyrolysis of oil shale and has the potential for efficient and economical oil shale in-situ mining. Meanwhile, hydraulic fracturing of oil shale reservoirs to create more fractures is also necessary to realize the success of in-situ mining.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Chen, B. et al. Studies of fast co-pyrolysis of oil shale and wood in a bubbling fluidized bed. Energy Convers. Manage. 205, 112356 (2020).

Yang, Q., Qian, Y., Zhou, H. & Yang, S. Conceptual design and techno-economic evaluation of efficient oil shale refinery processes ingratiated with oil and gas products upgradation. Energy Convers. Manage. 126, 898–908 (2016).

Khraisha, Y. H. Thermal analysis of shale oil using thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry. Energy Convers. Manage. 43, 229–239 (2002).

Jiang, H. et al. Effect of hydrothermal pretreatment on product distribution and characteristics of oil produced by the pyrolysis of Huadian oil shale. Energy Convers. Manage. 143, 505–512 (2017).

Khraisha, Y. H., Irqsousi, N. A. & Shabib, I. M. Spectroscopic and chromatographic analysis of oil from an oil shale flash pyrolysis unit. Energy Convers. Manage. 44(1), 125–134 (2003).

Yan, J., Jiang, X., Han, X. & Liu, J. A TG–FTIR investigation to the catalytic effect of mineral matrix in oil shale on the pyrolysis and combustion of kerogen. Fuel 104, 307–317 (2013).

Han, X., Kulaots, I., Jiang, X. & Suuberg, E. M. Review of oil shale semicoke and its combustion utilization. Fuel 126, 143–161 (2014).

Wang, Q., Ma, Y., Li, S., Hou, J. & Shi, J. Exergetic life cycle assessment of Fushun-type shale oil production process. Energy Convers. Manage. 164, 508–517 (2018).

Ar, B. Converting oil shale to liquid fuels: Energy inputs and greenhouse gas emissions of the shell in situ conversion process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 7489–7495 (2008).

Kang, Z., Zhao, Y. & Yang, D. Review of oil shale in-situ conversion technology. Appl. Energy 269, 115121 (2020).

Meng, F. et al. Experimental investigation on the pyrolysis process and product distribution characteristics of organic-rich shale via supercritical water. Fuel 333, 126338 (2023).

Aljariri Alhesan, J. S. et al. Long time, low temperature pyrolysis of El-Lajjun oil shale. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 130, 135–141 (2018).

Kruusement, K., Luik, H., Waldner, M., Vogel, F. & Luik, L. Gasification and liquefaction of solid fuels by hydrothermal conversion methods. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 108, 265–273 (2014).

Sun, Y. et al. Subcritical water extraction of huadian oil shale at 300 °C. Energy Fuels 33, 2106–2114 (2019).

Saeed, S. A. et al. Hydrothermal conversion of oil shale: Synthetic oil generation and micro-scale pore structure change. Fuel 312, 122786 (2022).

Toor, S. S., Rosendahl, L. & Rudolf, A. Hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass: A review of subcritical water technologies. Energy 36, 2328–2342 (2011).

Wang, L. & Weller, C. L. Recent advances in extraction of nutraceuticals from plants. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 17, 300–312 (2006).

Johnson, M. D., Huang, W., Dang, Z. & Weber, W. J. A distributed reactivity model for sorption by soils and sediments. 12. Effects of subcritical water extraction and alterations of soil organic matter on sorption equilibria. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33, 1657–1663 (1999).

Fei, Y. et al. Evaluation of several methods of extraction of oil from a Jordanian oil shale. Fuel 92, 281–287 (2012).

Hu, H., Zhang, J., Guo, S. & Chen, G. Extraction of Huadian oil shale with water in sub-and supercritical states. Fuel 78(6), 645–651 (1999).

Lewan, M. & Winters, J. M. JH, generation of oil-like pyrolyzates from organic-rich shales. Science 203, 897–899 (1979).

Yanik, J. et al. Characterization of the oil fractions of shale oil obtained by pyrolysis and supercritical water extraction. Fuel 74, 46–50 (1995).

Wang, Z. et al. Subcritical water extraction of Huadian oil shale under isothermal condition and pyrolysate analysis. Energy Fuels 28, 2305–2313 (2014).

El Harfi, C. B. K. et al. Supercritical fluid extraction of Moroccan (Timahdit) oil shale with water. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 50, 163–174 (1999).

Deng, S. et al. Sub-critical water extraction of bitumen from Huadian oil shale lumps. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 98, 151–158 (2012).

Sun, Y. et al. Pore evolution of oil shale during sub-critical water extraction. Energies 11, 842 (2018).

Kang, S. et al. The enhancement on oil shale extraction of FeCl3 catalyst in subcritical water. Energy 238, 121763 (2022).

Abdi-Khanghah, M., Wu, K. C., Soleimani, A., Hazra, B. & Ostadhassan, M. Experimental investigation, non-isothermal kinetic study and optimization of oil shale pyrolysis using two-step reaction network: Maximization of shale oil and shale gas production. Fuel 371, 131828 (2024).

Zhang, X., Guo, W., Pan, J., Zhu, C. & Deng, S. In-situ pyrolysis of oil shale in pressured semi-closed system: Insights into products characteristics and pyrolysis mechanism. Energy 286, 129608 (2024).

Pan, Y., Jia, Y., Zheng, J., Yang, S. & Bttina, H. Research progress of fracture development during in-situ cracking of oil shale. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 174, 106110 (2023).

Hu, X. et al. Study on the pyrolysis behavior and product characteristics of Balikun oil shale with different water pressures in sub-and supercritical states. Fuel 369, 131701 (2024).

Turakhanov, A. et al. Cyclic subcritical water injection into Bazhenov oil shale: Geochemical and petrophysical properties evolution due to hydrothermal exposure. Energies 14, 4570 (2021).

Chen, B., Han, X., Li, Q. & Jiang, X. Study of the thermal conversions of organic carbon of Huadian oil shale during pyrolysis. Energy Convers. Manage. 127, 284–292 (2016).

Kang, S. et al. Highly efficient catalytic pyrolysis of oil shale by CaCl2 in subcritical water. Energy 274, 127343 (2023).

Roald, B. R. T. S. & Leif, N. The role of alkenes produced during hydrous pyrolysis of a shale. Org. Geochem. 31, 1189–1208 (2000).

Wang, L. et al. Enhancing oil shale pyrolysis using metal-doped carbon quantum dot catalysts: A comprehensive behavioral, kinetic, and mechanistic analysis. Fuel 381, 133464 (2025).

Wang, L., Yang, D. & Kang, Z. Evolution of permeability and mesostructure of oil shale exposed to high-temperature water vapor. Fuel 290, 119786 (2021).

Gao, C., Zhang, Y., Wang, X., Lin, J. & Li, Y. Geochemical characteristics and geological significance of the anaerobic biodegradation products of crude oil. Energy Fuels 33, 8588–8595 (2019).

Spigolon, A. L. D., Lewan, M. D., de Barros Penteado, H. L., Coutinho, L. F. C. & Mendonça Filho, J. G. Evaluation of the petroleum composition and quality with increasing thermal maturity as simulated by hydrous pyrolysis: A case study using a Brazilian source rock with Type I kerogen. Org. Geochem. 83–84, 27–53 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Oil shale pyrolysis in a moving bed with internals enhanced by rapid preheating in a heated drop tube. Energy Convers. Manag. 224, 113358 (2020).

Pan, S. et al. Investigation of behavior of sulfur in oil fractions during oil shale pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 33, 10622–10637 (2019).

Askarova, A. et al. Thermal enhanced oil recovery in deep heavy oil carbonates: Experimental and numerical study on a hot water injection performance. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 194, 107456 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42202345), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province of China (No. 20242BAB20141), the Natural Science Foundation of Shangdong Province of China (No. ZR2024QD212), and the “Open Competition Mechanism to Select the Best Candidates” Projects of Ganzhou.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yihan Wang: Formal analysis, Writing-original draft. Shijie Kang: Methodology, Writing-review & editing. Lulu Jiao: Formal analysis, Data curation. Yalu Han*: Conceptualization. Zhao Liu: Formal analysis. Chengcai Jin: Formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Kang, S., Jiao, L. et al. Catalytic hydrothermal pyrolysis behaviors of oil shale under restrained conditions. Sci Rep 15, 21276 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05840-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05840-1