Abstract

Excretion of sodium and water through the skin as sweat represents a regulatory mechanism of electrolyte- and fluid balance. Since patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) exhibit increased skin sodium content, we investigated the feasibility of sweat testing as a novel experimental tool to provide a more complete assessment of fluid- and sodium status. In this cross-sectional feasibility study, we applied pilocarpine iontophoresis to induce sweat testing in 58 patients across various stages of CKD including kidney transplant recipients and a healthy control cohort (n = 6) to investigate possible effects of CKD and transplantation status on sweat weight and sodium concentration. Due to non-linear relationships, we modeled our data using polynomial regression. Decline of kidney function showed a significant association with lower sweat weight: adj R2 = 0.2278, F(2, 61) = 10.29, p = 0.0001. Sweat sodium concentrations were increased in moderate CKD, however, this effect was lost in end-stage kidney disease with and without requirement of hemodialysis: adj R2 = 0.3701, F(4, 59) = 10.26, p = 2.261e-06. Diagnostic sweat analysis represents an innovative, non-invasive option for a more thorough investigation of sodium- and fluid homeostasis in CKD. Lower sweat weight and higher sweat sodium concentrations represent a unique feature of CKD patients with potential therapeutic implications.

Trial registration: This study is registered at ClinTrials.gov with the study number NCT06354842.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The skin functions as a barrier between the human body and its surroundings, constantly adapting to temperature changes, contributing to thermoregulation through its ability to produce sweat, which can result in substantial loss of sodium and fluid under conditions of intense exercise or hyperthermia1,2. Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have a high cardiovascular risk and it has previously been reported that they accumulate more sodium in their skin compared to healthy persons3,4,5. Therefore, it has been discussed that decreased renal excretion of sodium and water in CKD patients contributes to arterial hypertension and promotes the formation of peripheral and pulmonary edemas6,7,8,9,10. Interestingly, accumulating evidence indicates a model of sodium- and urea-driven water conservation in the skin and the kidney that jointly affect the extracellular volume and systemic blood pressure11,12. These novel concepts and studies highlight the role of the skin barrier, in the pathogenesis of hypertension13. Indeed, skin sodium deposits have been shown to correlate with left-ventricular mass independent of fluid status and blood pressure in CKD patients4,14. The formation of skin- and muscle sodium deposits seem to be associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes; therefore, more comprehensive methods of investigating skin sodium and fluid regulation in humans are required to find out more about the regulatory principles behind this phenomenon15.

While previous reports have investigated the relationship between sodium intake, serum sodium concentration, urinary sodium levels and muscular and dermal sodium content, only few studies have assessed the dysregulated sodium- and fluid balance and its effects on sweat weight and composition in CKD2,16. We hypothesized that there are differences in sweat sodium concentration and sweat weight in patients with different CKD stages and after kidney transplantation. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the feasibility of measuring sweat weight and sodium concentrations in patients with different stages of CKD. To this end, we applied sweat testing via pilocarpine iontophoresis to patients with varying stages of CKD as well as kidney transplant recipients to investigate the feasibility and validity of this method. Sweat testing via pilocarpine iontophoresis is an established method in clinical routine for the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis with unknown potential for wider clinical application17. We conducted the current study to evaluate if pilocarpine iontophoresis is feasible in patients with different CKD stages and after kidney transplantation regarding the detectability of differences in sweat sodium concentration and sweat weight.

Results

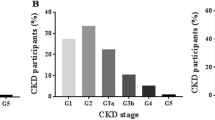

Descriptive statistics and mean values for sweat weight and sweat sodium concentrations for each CKD stage as well as the whole cohort are provided in Table 1. A summary of relevant co-morbidities and medications of the participating subjects is provided in Table 2. As described in the Methods section, patients with varying stages of kidney disease and varying transplantation status (Tx) as well as a group of healthy control individuals (Control) were subjected to standardized sweat testing. Our results show the feasibility of pilocarpine iontophoresis-based sweat collection in detecting differences in sweat weight and sweat sodium concentration in patients with different stages of CKD and after kidney transplantation. Additional criteria also indicate feasibility like a sweat collection time of 25 min, a dropout rate of 0% and no significant side effects.

Sweat weight

A second-degree polynomial model was chosen for final reporting as it resulted in the highest robustness and best overall fit while avoiding the problem of overfitting and is thus reported here (Fig. 1). Transplantation status did not significantly contribute to the model and was thus omitted as an independent variable in the final model. Sweat weight progressively declined with CKD stage with a steeper slope from CKD IIIb onwards. Interestingly, a gender specific difference was observed. Male CKD patients displayed a higher sweat weight compared to females (Fig. 2). Sweat weight did not correlate significantly with creatinine-based eGFR (Supplemental Fig. 3).

A second degree polynomial model consisting of CKD stage as a numerical linear vector significantly predicts sweat weight: adj R2 = 0.2278, F(2, 61) = 10.29, p = 0.000141. Sweat weight (corresponding to sweat weight per surface area after standardized stimulation) decreases with CKD stage, with a steeper slope in ESKD. Model term: Sweat weight (g) = 0.17333-0.43217*(CKD stage)-0.11351*(CKD stage)2.

Sweat sodium concentration

Similar to sweat weight, a second-degree polynomial model resulted in the most robust prediction of sweat sodium. Transplantation status contributed significantly to the model. Sweat sodium concentrations increased with CKD stage until reaching a turning point at CKD stage IIIb, at which point a further increase in CKD stage was associated with regressing sweat sodium concentrations (Fig. 3). Kidney graft recipient status was significantly associated with higher sweat sodium concentrations.

A second degree polynomial model consisting of transplantation status and CKD stage as a numerical linear vector significantly predicts sweat sodium concentration: adj R2 = 0.3701, F(4, 59) = 10.26, p = 2.261e-06. Sweat sodium concentration is increased in moderate CKD and regresses to values comparable to healthy controls in ESKD. Model term: Sweat sodium concentration (mmol/L) = 30.846–13.953*(CKD stage)-65.431*(CKD stage)2 + 79.095*(Tx).

Serum sodium concentrations did not significantly correlate with sweat sodium concentration (Supplemental Fig. 1). Furthermore, sweat sodium concentration did not correlate significantly with creatinine-based eGFR (Supplemental Fig. 4). Additionally, there was no significant difference in sweat sodium concentration between patients receiving RAAS inhibition (RAASi) and patients without RAASi (Supplemental Fig. 5).

Discussion

We report on a clinical trial investigating the feasibility of sweat testing via pilocarpine iontophoresis as a novel tool for more in-depth analysis of fluid- and sodium homeostasis in patients affected with CKD.

Primarily and in accordance with our hypothesis, the amount of excreted sweat exhibited a decline with CKD stage which accelerated in CKD IV with a clear drop towards end-stage kidney disease on hemodialysis (ESKD/HD) supporting the theory of a water conserving principle in these patients. Previous research showed that a high salt load leads to lower local sweat weight, which adds to the theory of sodium retention and tissue accumulation in patients with CKD associating with water retention16. These findings strengthen the above-described hypothesis that a decline in kidney function affects the physiologic skin barrier at different levels.

Additionally, we found an increase in sweat sodium concentrations with progression of CKD and in kidney transplant recipients, compared to ESKD/HD patients and healthy controls displaying similar sodium concentrations. Interestingly, probably due to the restrictions of creatinine-based eGFR in subjects with early-stage CKD or no CKD, both polynomial and linear regression models between sweat weight / sweat sodium concentration and eGFR did not reach statistical significance after exclusion of ESKD/HD patients, in which creatinine-based calculation cannot be meaningfully interpreted (Supplemental Figs. 3, 4). As there are few previous reports investigating the relationship between kidney function and sweat composition, it is difficult to draw physiological and clinical conclusions18. However, it has been previously reported that ESKD/HD patients exhibit an accumulation of sodium deposits in their skin, with deleterious effects on their cardiovascular clinical outcomes19. We speculate that the increase in sweat sodium concentration in CKD may represent a defect in the skin barrier resulting simultaneously in the observed lower sweat weight in these patients. According to our hypothesis these effects might be a compensatory mechanism of the body to conserve water. However, this clearly needs further investigation in future studies.

In line with this hypothesis, preclinical data have shown that severe kidney disease leads to a strong tendency towards generalized water- and sodium retention to prevent water loss, which could provide an additional explanation for our findings11. In ESKD/HD patients this regulatory principle might be affected by the typically three hemodialysis sessions per week with sodium-containing dialysate combined with removal of free body water, with the resulting sodium retention representing an unsolved problem of extracorporeal kidney replacement therapy20. Interestingly, perspiration therapy had been discussed as a therapeutic regimen of interest in the 1960s as it can address several disadvantages associated with hemodialysis: clearance of free fluid through the skin thereby limiting inter-dialytic weight gain, enforced excretion of sodium and potassium (potentially resulting in measurable improvements in systemic electrolyte balance) as well as increased removal of uremic toxins21,22,23,24,25. While perspiration therapy does not currently play a role in modern nephrology, recently scientific interest has regained traction with calls for further research into the effectiveness of this method in ESKD during recent years23,26. Notably, sweating has recently also been identified as a potential therapeutic avenue in congestive heart failure27. A study has recently demonstrated the feasibility of urea monitoring in ESKD/HD patients in saliva and sweat, further highlighting the potential of this field of research28.

To date, sweat weight and sweat electrolyte concentrations have been rarely researched in CKD patients. In this study we measured sweat weight and electrolyte concentrations with a standardized method in subjects with various stages of impaired kidney function and transplant recipients, while most previous studies measured sweat in athletes and healthy individuals2. We identified a single previous report on sweat weight and sodium levels in advanced CKD, which is in line with our results18.

Consequently, sweat testing via pilocarpine iontophoresis may represent a promising analyzing tool towards a more complete assessment of fluid- and sodium analysis in patients with CKD but also with other chronic diseases. Preliminary analysis (data not shown) indicates high potential of this analysis method in patients with systemic diseases (e.g., systemic sclerosis). Our findings support the theory for the existence of a disturbed skin barrier in CKD and other systemic diseases resulting in increased skin sodium retention (as observed in 23Na-MRI studies) in CKD patients combined with an impaired sweat excretion through the skin. Due to the exploratory design of our study these findings will require further studies in larger patient collectives. Combined with techniques like 23Na-MRI, sweat testing via pilocarpine iontophoresis might allow future research to better understand basic regulatory mechanisms of sodium and fluid homeostasis in patients with CKD at high cardiovascular risk and help to pave the way for novel therapeutic approaches19.

Limitations result mostly from the exploratory nature of our study, which therefore will require further independent validation in larger and age-matched patient cohorts. Analysis of induced sweat can be severely impacted by methodological errors in adults, which is why standardized testing and analysis protocols are needed29,30. Additionally, our feasibility study was not powered to detect changes induced by CKD stage and transplantation status reported here and these conclusions will require additional validation.

Another limiting point is that correlations based on eGFR cannot be meaningfully done in ESKD/HD patients and would have required more sensitive and invasive methods than serum-creatinine based eGFR in healthy individuals and very early CKD stages, so we have calculated our analysis against CKD stages. This assumes a linear progression of CKD through the KDIGO stages18, which does not accurately represent reality but may yet allow for useful analysis. In the present study, 16 participants received diuretic medication that might have led to lower sweat sodium concentrations and have impacted the results. However, a supporting analysis of the effects of diuretic treatment on sweat sodium concentrations and sweat weight with CKD stage-matched controls from our sample did not demonstrate a statistically significant effect in this population (Supplemental Fig. 2). Measured sweat weight was overall significantly higher in men (Fig. 3), which is in line with existing literature, we accounted for it by largely balancing sex distribution within our study population (Table 2) and thus sex differences are unlikely to have affected our analysis in an impactful way2,18.

We have demonstrated the feasibility of pilocarpine sweat testing in patients with CKD and we have also detected a lower sweat weight and increased sweat sodium concentrations in these patients. This specific method could help to address open research questions regarding fluid- and sodium homeostasis in CKD patients. The analysis of sweat weight and electrolytes could serve as an additional diagnostic and potentially prognostic method for patients affected with CKD and other patient cohorts at high cardiovascular risk. Research into sweat testing in CKD has recently gained traction with sweat biomarkers for CKD and passive sweat collection systems becoming available31,32. Further studies will be required to investigate the true potential of this method in CKD and other systemic diseases, to elucidate the pathophysiology and implications of reduced sweat weight.

We hope that the results of this study could pave the way for further research in this area in CKD patients to reduce the high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in this peculiar patient cohort.

Methods

Study design

In this cross-sectional feasibility study, sweat sodium concentrations and standardized sweat weight was measured via pilocarpine iontophoresis in 58 CKD patients of varying stages including ESKD/HD patients and kidney transplant recipients as well as in 6 healthy controls. Further study related assessments included laboratory parameters (serum creatinine, serum sodium concentrations), anthropometric parameters (age, weight, height, BMI) as well as non-invasive blood pressure measurements and a thorough medical history including daily medications. To improve clarity of the manuscript, we calculated eGFR but only provided CKD stages as eGFR from serum creatinine cannot be meaningfully interpreted in ESKD/HD patients and does not reliably reflect true creatinine clearance with satisfactory accuracy in normal or mildly impaired kidney function33. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria (No. 1889/2017) and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted according to good clinical practice guidelines of the Medical University of Vienna.

Study population

Suitable subjects were identified during routine visits at the outpatient clinic of the Division of Nephrology and Dialysis at the General Hospital of Vienna or during their routine dialysis session and were screened for eligibility and approached for informed consent. The healthy control group was recruited after careful anamnesis among co-workers at the General Hospital of Vienna.

The participants were assigned a randomly generated unique code to provide pseudo-anonymity of the acquired samples after obtaining written, informed consent.

General inclusion criteria were a completed 18th year of life and the ability and willingness to provide informed consent. General exclusion criteria were signs of acute infection, clinical signs of kidney graft rejection or pregnancy. Exclusion criteria for the healthy controls were pregnancy or the presence of chronic metabolic, renal, cardiovascular (coronary heart disease, peripheral artery disease, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack or aortic aneurysm), or rheumatologic conditions, hypertension, chronic or recent intake (8 weeks prior to testing) of psychiatric or antihypertensive medication.

Sweat sampling and analysis

The eccrine sweat glands on the inner forearm were stimulated via pilocarpine iontophoresis using electro-stimulation in accordance with instructions provided by the manufacturer (‘Stimulette Lx, Schuhfried Medizintechnik’, Vienna, Austria). The method is described in detail elsewhere34. Briefly, two electrodes were placed on the forearm, of which the anode was covered with a fabric soaked in pilocarpine solution and the cathode was covered with a fabric soaked in a 0.9% sodium chloride solution for better conductivity. Afterwards, we applied 3 mA direct current through the electrodes for the duration of five minutes under a room temperature of 22 °C and humidity of 60%. All patients were recommended to restrict their dietary sodium intake to 2 g per day according to the KDIGO 2020 and 2024 guidelines33,35. Patients and healthy subjects were instructed to keep five minutes in a resting sitting position before pilocarpine iontophoresis was initiated. During the stimulation, the pilocarpine followed the direct current and induced sweat secretion in the eccrine sweat glands of the skin.

After stimulation, the surface was cleaned again to prevent any contamination. Afterwards, a filter paper was applied to the previously stimulated area and covered with a clear foil. This filter paper collected the sweat for 20 min. The collected sweat was then weighed, diluted and frozen until further processing. Sodium concentrations in sweat were determined by flame photometry at the routine diagnostics laboratory of the Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine at the General Hospital of Vienna.

To normalize the individual sweat weights and thereby standardize the testing, the amount of the weight of the collected sweat was measured on a precision scale and was used as an indicator for the sweat weight.

In female subjects and patients there were no adjustments of sweat collection timepoint in relation to the menstrual cycle, since it is known that anovulatory cycles, premature menopause and menstrual disorders are associated with female patients with CKD or ESKD36.

Statistical analysis

The results of the study were analyzed using R version 4.3.2 (R foundation, Vienna, Austria) and R Studio version 2023.06.0 + 421 (Posit PBC, Boston, MA, USA) with the library packages ggpubr, car, caret and tidyverse. Additionally, GraphPad Prism version 10.2.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc, California, USA) was used for supplementary statistical analyses.

Model construction and cross-validation

We hypothesized that CKD stage and transplantation status predict sweat weight (measured as sweat weight excreted during standardized testing) and sweat sodium concentration. Subjects were classified into CKD stages after the presence of acute renal failure was excluded in accordance with current KDIGO guidelines33. To determine the patient’s CKD stage, creatinine-based eGFR equation (MDRD formula) was used. Serum creatinine was determined during the last routine venipuncture prior to sweat collection. In a first step, we plotted CKD stage as a linear numerical vector ranging from healthy controls (represented in the model as the value 1) to ESKD/HD (represented in the model as the value 8) against sweat weight- and sweat sodium concentration for initial visual inspection. As this did not convincingly suggest the presence of a linear relationship, we proceeded to construct polynomial regression models with varying degrees of polynomial. To this end, we divided our data into a training- and testing dataset and applied k-fold cross validation. Finally, the most robust model was fitted onto the whole dataset and reported. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics are provided as mean ± SD unless stated otherwise.

Data availability

All raw and processed data can be accessed upon request after contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESKD/HD:

-

End stage kidney disease on hemodialysis

- 23Na+ MRI:

-

Sodium magnetic resonance imaging

- RAASi:

-

Renin angiotensin aldosterone inhibition

- Tx:

-

Transplantation

- mA:

-

Milliampere

References

Shiohara, T., Sato, Y., Komatsu, Y., Ushigome, Y. & Mizukawa, Y. Sweat as an efficient natural moisturizer. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 51, 30–41 (2016).

Baker, L. B. Physiology of sweat gland function: The roles of sweating and sweat composition in human health. Temperature (Austin) 6, 211–259 (2019).

Dahlmann, A. et al. Magnetic resonance-determined sodium removal from tissue stores in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 87, 434–441 (2015).

Schneider, M. P. et al. Skin sodium concentration correlates with left ventricular hypertrophy in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 1867–1876 (2017).

Borrelli, S. et al. Sodium intake and chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4744 (2020).

Bobkova, I., Chebotareva, N., Kozlovskaya, L. & Shilov, E. Edema in renal diseases – current view on pathogenesis. Nephrol. Point Care https://doi.org/10.5301/pocj.5000204 (2016).

Shin, J. & Lee, C. H. The roles of sodium and volume overload on hypertension in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 40, 542–554 (2021).

Yu, A. S. L. et al. Brenner & Rector’s the Kidney 11th edn. (Elsevier, 2020).

Hostetter, T. H. et al. Cardiorenal hemodynamics and sodium excretion in rats with myocardial infarction. Am. J. Physiol. 245(1), H98-103 (1983).

Paller, M. S. & Schrier, R. W. Pathogenesis of sodium and water retention in edematous disorders. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2(2), 241–54 (1982).

Kovarik, J. J. et al. Adaptive physiological water conservation explains hypertension and muscle catabolism in experimental chronic renal failure. Acta Physiol. (Oxford) 232, e13629 (2021).

Wild, J. et al. Aestivation motifs explain hypertension and muscle mass loss in mice with psoriatic skin barrier defect. Acta Physiol. (Oxford) 232, e13628 (2021).

Just, A. Hypertension due to loss of water. Acta Physiol. 232, e13658 (2021).

Dini, F. L. et al. Left ventricular mass and thickness: Why does it matter?. Heart Fail. Clin. 15, 159–166 (2019).

Kopp, C. et al. 23Na magnetic resonance imaging-determined tissue sodium in healthy subjects and hypertensive patients. Hypertension 61, 635–640 (2013).

Braconnier, P. et al. Short-term changes in dietary sodium intake influence sweat sodium concentration and muscle sodium content in healthy individuals. J. Hypertens. 38, 159–166 (2020).

Farrell, P. M. et al. Diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: Consensus guidelines from the cystic fibrosis foundation. J. Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.064 (2017).

Yosipovitch, G. et al. Sweat electrolytes in patients with advanced renal failure. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 124, 808–12 (1994).

Salerno, F. R. et al. Outcomes and predictors of skin sodium concentration in dialysis patients. Clin. Kidney J. 15, 1129–1136 (2022).

Lew, S. Q. et al. The role of intra- and interdialytic sodium balance and restriction in dialysis therapies. Front. Med. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1268319 (2023).

Keller, R. W., Bailey, J. L., Wang, Y., Klein, J. D. & Sands, J. M. Urea transporters and sweat response to uremia. Physiol. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1481/phy2.12825 (2016).

Al-Tamer, Y. Y. & Hadi, E. A. Sweat urea, uric acid and creatinine concentrations in uraemic patients. Urol. Res. 25, 337–40 (1997).

Keller, R. W. Jr., Kopple, J. D. & Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Perspiration interventions for conservative management of kidney disease and uremia. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 29, 57–63 (2020).

Pruijm, M. et al. Stimulated sweating as a therapy to reduce interdialytic weight gain and improve potassium balance in chronic hemodialysis patients: a pilot study. Hemodial. Int. 17(2), 240–248 (2013).

Lacher, J. W. & Schrier, R. W. Sweating treatment for chronic renal failure. Nephron 21(5), 255–259 (1978).

Hanafusa, N., Lodebo, B. T., Shah, A. & Kopple, J. D. Is there a role for diaphoresis therapy for advanced chronic kidney disease patients. J. Renal Nutr. 27, 295–302 (2017).

Aronson, D. et al. Enhancing sweat rate using a novel device for the treatment of congestion in heart failure. Circul. Heart Fail. 16, e009787 (2023).

Adelaars, S. et al. The correlation of urea and creatinine concentrations in sweat and saliva with plasma during hemodialysis: an observational cohort study. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-1285 (2024).

Baker, L. B. Sweating rate and sweat sodium concentration in athletes: A review of methodology and intra/interindividual variability. Sports Med. 47, 111–128 (2017).

Willems, P., Weekx, S., Meskal, A. & Schouwers, S. Biological variation of chloride and sodium in sweat obtained by pilocarpine iontophoresis in adults: How sure are you about sweat test results?. Lung 195, 241–246 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Passive sweat collection and colorimetric analysis of biomarkers relevant to kidney disorders using a soft microfluidic system. Lab Chip. 19, 1545–1555 (2019).

Shankar, V. et al. Identification of end-stage renal disease metabolic signatures from human perspiration. Nat. Sci. 3, e20220048 (2023).

Stevens, P. E. et al. KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 105(4S), 117–314 (2024).

LeGrys, V. A. et al. Sweat Testing: Sample Collection and Quantitative Chloride Analysis; Approved Guideline - Third Edition. CLSI document C34-A3. (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2009).

De Boer, I. H. et al. KDIGO 2020 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 98(4S), 1–115 (2020).

Ahmed, S. B. & Ramesh, S. Sex hormones in women with kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 31(11), 1787–1795 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The idea for the study was conceived by J.J.K. The original collection of data and samples was done by T.S., F.L. and C.C.K. Analyses were performed by B.M., S.G. and K.G.S. Statistical analysis was performed by O.H. The draft manuscript was written by T.S., J.H., M.D.S and J.J.K. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shoumariyeh, T., Logar, F., Helk, O. et al. Decline of kidney function is associated with lower sweat weight in patients with chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep 15, 22518 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05855-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05855-8