Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) combined with conventional cytotoxic agents have become the new standard of care for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (SCLC). The platinum-based agents in these regimens are highly emetogenic, necessitating prophylactic antiemetic steroids. This study evaluated the impact of prophylactic antiemetic steroid use on survival outcomes and efficacy in patients with SCLC undergoing combination therapy. Using data from the National Health Insurance Service of Korea database, patients treated with atezolizumab, etoposide, and carboplatin between 2020 and 2022 were categorized by antiemetic steroid dosage. Primary outcomes included overall survival (OS) and time to next treatment (TTNT), assessed using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. After propensity score matching, 2,116 patients were categorized into low-dose (0–12 mg), moderate-dose (13–24 mg), and high-dose (25–36 mg) groups. Median OS was 10.2 months (interquartile range [IQR] 5.2–18.5), and median TTNT was 8.6 months (IQR 4.8–15.5), with no significant differences among groups. Subgroup analysis revealed increased mortality associated with higher antiemetic steroid doses in patients concurrently receiving non-antiemetic steroids. Although antiemetic steroids did not significantly impact survival outcomes overall, reducing their dosage in patients already on steroid therapy for other indications is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for approximately 10–15% of all lung cancer cases, and is characterized by rapid growth, high responsiveness to chemotherapy, and unfavorable long-term prognosis1. For more than 20 years, the first-line treatment for extensive-stage SCLC has been chemotherapy alone, typically involving etoposide and platinum-based agents. The introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in the past decade has shown that immunotherapies could potentially yield beneficial outcomes in patients diagnosed with SCLC because a high tumor mutation burden is expected to trigger a strong T-cell response2. ICI monotherapy has yielded limited―but persistent―efficacy in patients with refractory SCLC3,4. However, combining ICI with the standard cytotoxic chemotherapy has significantly improved clinical outcomes. Following the IMPOWER 133 study5, the Food and Drug Administration approved a combination of atezolizumab, etoposide, and carboplatin for first-line treatment of extensive-stage SCLC in 2019. Since then, the combination of durvalumab, etoposide, and platinum has demonstrated clinical efficacy6, establishing ICIs combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy as the new standard of care for extensive-stage SCLC7.

ICIs are a new class of anticancer agents that kill tumor cells by inhibiting the immune evasion mechanisms of T cells, including programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), PD ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4). Consequently, concurrent use of medications that affect immune function, such as antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), immunosuppressants, and steroids, may alter the efficacy of ICIs and reduce the odds of survival8,9,10.

Steroids, in particular, are used to control various symptoms in patients with cancer. Although numerous studies have shown that steroids can reduce the efficacy of ICIs, the use of antiemetic steroids is essential when combining ICIs with highly emetogenic cytotoxic chemotherapy. Clinical trials and international guidelines have reported inconsistencies regarding the use of antiemetic steroids in this context11,12. Moreover, there is a lack of clear clinical evidence supporting their use. In this study, we analyzed the effect of antiemetic steroids administered as first-line therapy with atezolizumab, etoposide, and carboplatin on survival in patients diagnosed with extensive-stage SCLC in a real-world setting.

Results

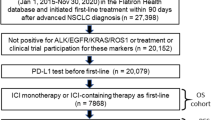

In this study, a total of 2,868 patients with extensive-stage SCLC who received atezolizumab, etoposide, and carboplatin between August 1, 2020, and June 30, 2022, were included. Patients were categorized into three groups based on the total dose of antiemetic dexamethasone administered per first chemotherapy cycle: low-dose (0–12 mg), moderate-dose (13–24 mg), and high-dose (25–36 mg). Among the 2,868 patients, 1,563 were assigned to the low-dose group, 681 to the moderate-dose group, and 624 to the high-dose group (Fig. 1). After 2:1:1 propensity score matching, data from 2,116 patients were included in the study, with no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics among the 3 groups (Table 1). The mean (± SD) dose of antiemetic dexamethasone was 3.8 (± 3.9) mg in the low-dose group, 18.4 (± 4.5) mg in the moderate-dose group, and 32.4 (± 3.6) mg in the high-dose group.

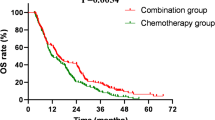

In the overall population, the median treatment duration with atezolizumab was 4.6 months (interquartile range [IQR] 2.8–6.1), the median overall survival (OS) was 10.2 months (IQR 5.2–18.5), and the median time to next treatment (TTNT) was 8.6 months (IQR 4.8–15.5). The results by antiemetic steroid dosage were as follows: in the low-dose group, the median OS was 10.4 months (IQR 5.2–18.5), with the median TTNT of 8.6 months (IQR 4.7–15.2). For the moderate-dose group, the median OS was 10.0 months (IQR 5.6–18.1) with the median TTNT of 8.7 months (IQR 5.1–15.3). In the high-dose group, the median OS was 10.1 months (IQR 5.2–19.1) with the median TTNT of 9.1 months (IQR 4.7–16.8). There were no statistically significant differences in OS and TTNT among the 3 groups based on antiemetic steroid dosage (Fig. 2).

Multivariable analysis revealed that older age groups (65–79 and ≥ 80 years), history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) or pneumonitis, and concomitant use of opioids, antibiotics, and PPIs/potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs) were statistically significantly associated with inferior OS and TTNT. However, there were no statistically significant differences in the OS and TTNT hazard ratios (HRs) according to the dosage of antiemetic steroids (Table 2).

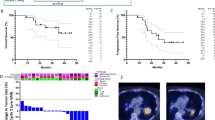

Subgroup analysis according to age and sex confirmed that the dosage of antiemetic steroids had no effect on OS or TTNT. In patients who received non-antiemetic steroids with a dexamethasone equivalent dose of ≥ 10 mg, the HR of OS was significantly higher in the antiemetic high-dose steroid group at 1.24 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.53). However, no significant differences in the HR for TTNT were observed between the moderate- and high-dose groups (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Despite their immunosuppressive properties, antiemetic steroids are often used in combination with ICIs and highly emetogenic chemotherapy in clinical settings. This study used information from a large claims database to examine the influence of antiemetic steroids on the survival of patients with SCLC undergoing combination ICIs and chemotherapy. The use of this antiemetic steroid did not significantly affect patient survival or treatment failure. However, in an additional examination of patients who used corticosteroids ≥ 10 mg (in dexamethasone equivalents) for non-antiemetic purposes within 3 weeks after initiating ICIs, we found that the risk of mortality was significantly increased by 24% among those who were administered a total of 25–36 mg of antiemetic dexamethasone during the initial chemotherapy cycle.

The study participants were administered an average dosage of 14.6 mg of antiemetic dexamethasone. This study found that more than one-half of patients (1,563 of 2,868) were taking ≤ 12 mg antiemetic steroids, which is below the recommended level. Among the chemotherapy regimens administered to the patients in this study, carboplatin was categorized as a moderate- or high-risk emetogenic agent, depending on the specific guidelines and dosage used13,14. The moderate emetogenic risk associated with carboplatin, as indicated in some recommendations, may explain this, along with the clinician’s adjustment of steroid dosage to accommodate the concurrent use of ICIs.

The use of supportive or baseline steroids in patients receiving ICIs can adversely affect survival10,15. The effects of administering antiemetic steroids remain unclear. The most recent guidelines indicate that there is insufficient clinical evidence to rule out the use of antiemetic steroids when administering ICIs along with chemotherapy11. However, a preclinical investigation in the context of chemoimmunotherapy found that administering dexamethasone at sufficiently high dosages to promote lymphodepletion had a negative impact on treatment response16.

Our investigation revealed that the use of antiemetic steroids did not have any significant effect on the OS of patients with SCLC undergoing immunochemotherapy. Previous studies investigating patients with breast cancer and non-small cell lung cancer―although limited in size and conducted retrospectively-have similarly shown that the use of preventive steroids along with ICIs and chemotherapy is not associated with any survival disadvantages1718. This could possibly be explained by the combined impact of chemotherapy and ICIs counteracting the influence of steroids. Cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents also affect the host immune system and enhance the immunological state of the tumor microenvironment. Combining these medications with immunotherapy can induce a therapeutic response in cancers that have not previously responded to ICIs alone19. Preclinical research in a chemoimmunotherapy environment has shown that the adverse effects of steroids are minimized when chemotherapy is combined with ICIs, resulting in greater efficacy16. Moreover, SCLC is characterized by a notably high chemotherapeutic response rate; however, only a small percentage of patients experience a sustained effect from a combination of ICIs2. This may have reduced the effect of antiemetic steroids on the therapeutic efficacy of ICIs. Furthermore, a limited number of patients in this study did not receive steroids, thereby precluding a definitive assessment of the steroid effect.

A subgroup analysis revealed a significant increase in the likelihood of mortality among individuals who used high-dose antiemetic steroids and consumed > 10 mg of steroids for non-antiemetic reasons. The immunosuppressive mode of action of steroids is well-known, and excessive doses of steroids may have detrimental effects on survival. Therefore, reducing the superfluous administration of steroids is crucial. This study suggests that if steroids are required for non-antiemetic purposes, it is advisable to limit the antiemetic steroid dosage to ≤ 24 mg, particularly in patients undergoing combination ICI and chemotherapy. Additionally, recent research has cast doubt on the effectiveness of steroids in preventing nausea. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend tailoring the use of antiemetic steroids to each patient or selecting an antiemetic regimen that excludes steroids14. In a retrospective analysis, no statistically significant differences were observed in the occurrence of nausea and vomiting when olanzapine was substituted with steroids in patients undergoing immunochemotherapy20.

In this study, multivariable analysis demonstrated a strong correlation between age, IPF, opioids, antibiotics, and PPIs, and the risk for mortality. This study specifically involved real-world evidence from populations that have often been excluded from previous clinical trials. Patients with a history of IPF or pneumonitis had increased mortality rates, consistent with other investigations21,22. Cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disease, and HBV infection are exclusion criteria because they may influence the worsening or recurrence of pre-existing disorders rather than the efficacy of ICIs23,24,25. Thus, no association with mortality was observed in this study. Moreover, the effects of the concurrent medications were comparable to those reported in other studies9,26,27.

This is the first study to investigate the effects of antiemetic steroids in patients with SCLC undergoing immunochemotherapy. Using extensive claims data enabled broad applicability, and the incorporation of additional concurrent medications is of substantial importance. Nevertheless, this study had some limitations. First, it was not possible to clearly determine the purpose and timing of steroid prescriptions due to limited information in the claims data. Steroids used for antiemetic purposes were classified based only on the date of anticancer medicine prescription. Second, inadequacies in claims data may lead to an overestimation of comorbidities and concomitant medication use rates. Third, the shorter follow-up period of the TTNT may have led to inadequate time for observing the results, thus preventing the detection of a meaningful effect. Therefore, in the subgroup analysis, the effect of higher doses of antiemetic steroids on OS was statistically significant; however, the effect on TTNT was not significant. Fourth, due to the inherent limitations of claims data, detailed information on radiotherapy regimens could not be obtained. Although the administration of radiotherapy following chemoimmunotherapy may have influenced survival outcomes, this factor could not be considered in our analysis and should be acknowledged as a limitation of the study.

In conclusion, results of this study demonstrated that, in patients with SCLC receiving immunochemotherapy, the use of antiemetic steroids did not adversely affect survival. However, in patients receiving steroids for other purposes, a higher dose of antiemetic steroids was associated with lower survival, suggesting the need to reduce antiemetic dose. Nevertheless, additional prospective studies are required to validate these findings.

Methods

Data source

The present study used a customized claims dataset provided by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), which included all patients diagnosed with lung cancer (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD-10] codes: C33 and C34) between 2020 and 2022. This database contains demographic information including age, sex, insurance type, diagnosis code, medical services, and prescribed medication information for 98% of the population of Korea. The date of death in the NHIS is linked to the Statistics Korea records. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University College of Medicine and Seoul National University Hospital (No. E-2301-074-1395). The Institutional Review Board waived the requirement for informed consent from participants as de-identified data were used in this study. All procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Patient selection

This study included adult patients ≥ 18 years of age who received atezolizumab, etoposide, and carboplatin concurrently between August 1, 2020 and June 30, 2022. This combination therapy has been reimbursed in Korea since August 1, 2020, for the first-line treatment of extensive-stage SCLC. Since reimbursement for this regimen in Korea requires a confirmed diagnosis of extensive-stage SCLC, patients who received this combination therapy were considered to have extensive-stage disease. Patients who were prescribed other chemotherapies within 6 months before the first dose of atezolizumab and those for whom hospital stay exceeded 21 days at the time of the first dose of atezolizumab, were excluded.

Antiemetic steroids were classified as dexamethasone, prescribed within 3 days after the start of chemotherapy at a maximum dose of 36 mg, because the exact reason for the prescription could not be determined due to limitations of the claims data. In addition, it is noteworthy that, while steroids may be administered to prevent nausea and vomiting during the first 4 cycles, the use of steroids, particularly at the start of ICI treatment, may interfere with effectiveness28,29. As such, patients were classified into low-dose (0–12 mg), moderate-dose (13–24 mg), and high-dose (25–36 mg) groups based on the antiemetic steroid dose administered in the first cycle, in accordance with the clinical guidelines, which recommend a maximum dexamethasone dose of 12 mg per day and up to 36 mg per chemotherapy cycle for antiemetic prophylaxis14. When an injection formulation of dexamethasone was prescribed and the exact dosage could not be determined from the claims data, 1 ampule containing 5 mg was assumed to be administered at 4 mg, based on the guidelines and common practice.

Patients were matched in a 2:1:1 ratio among the three groups using a propensity score calculated based on sex, age, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), hospital type, central nervous system (CNS) metastasis, history of radiation therapy, comorbid diseases, and exclusion criteria in the IMPOWER 133 study5. Comorbid diseases included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, rheumatic disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease and renal disease. Exclusion criteria included a history of autoimmune disease, IPF or pneumonitis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, solid organ transplantation, or cardiovascular disease (Supplementary Table 1). The abovementioned comorbidities and exclusion criteria were identified via diagnostic codes within 6 months before the first dose of atezolizumab.

Concomitant medications included steroids for other purposes, opioids, antibiotics, PPIs, P-CABs and immunosuppressants administered within 21 days of the first dose of atezolizumab (Supplementary Table 2).

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were OS and TTNT. OS was defined as the time from the first dose of atezolizumab to the date of death, and TTNT was defined as the time from the first dose of atezolizumab to the start of the next chemotherapy regimen15. For patients who did not receive the next chemotherapy regimen, TTNT was defined as the time to death or the time to the last recorded visit before December 31, 2022. The observation period for OS data was extended from the first dose of atezolizumab to the date of death or August 30, 2023, whichever occurred first. The observation period for TTNT data was extended from the first dose of atezolizumab to the date of the event or December 31, 2022. The primary outcomes across subgroups based on age, sex, and steroid dosage used for purposes other than antiemetic use were also compared. Steroid use for non-antiemetic purposes were calculated in daily dexamethasone equivalent doses (Supplementary Table 3), and the non-antiemetic steroid dosage was further categorized into 2 groups for analysis: < 10 mg; and ≥ 10 mg.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics were analyzed using the chi-squared test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). HRs for OS and TTNT were calculated using a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. These ratios were adjusted for demographic factors, such as sex, age, smoking status, BMI, hospital type, CNS metastasis, history of radiation therapy, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, comorbid diseases, exclusion criteria in the IMPOWER 133 study, and concomitant medications. The HRs are expressed with corresponding 95% CI. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate median OS. All data processing and statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R Studio 1.4.1717 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Data availability

The datasets for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chae, Y. K. et al. Recent advances and future strategies for immune-checkpoint inhibition in small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer. 18, 132–140 (2017).

Rudin, C. M., Brambilla, E., Faivre-Finn, C. & Sage, J. Small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7, 3 (2021).

Ready, N. et al. Third-line nivolumab monotherapy in recurrent SCLC: checkmate 032. J. Thorac. Oncol. 14, 237–244 (2019).

Chung, H. C. et al. Pembrolizumab after two or more lines of previous therapy in patients with recurrent or metastatic SCLC: results from the KEYNOTE-028 and KEYNOTE-158 studies. J. Thorac. Oncol. 15, 618–627 (2020).

Horn, L. et al. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 2220–2229 (2018).

Goldman, J. W. et al. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide alone in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): updated results from a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 22, 51–65 (2021).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2024). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sclc.pdf (accessed 30 Sep).

Wilson, B. E., Routy, B., Nagrial, A. & Chin, V. T. The effect of antibiotics on clinical outcomes in immune-checkpoint blockade: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 69, 343–354 (2020).

Lopes, S. et al. Do proton pump inhibitors alter the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients? A meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 14, 1070076 (2023).

Petrelli, F. et al. Association of steroids use with survival in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers. 12, 546 (2020).

Hesketh, P. J. et al. Antiemetics: ASCO guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 2782–2797 (2020).

Park, S. M., Kim, Y. J. & Lee, J. Y. Inconsistency in steroid use as antiemetics in clinical trial protocols involving immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with chemotherapy. Cancer Med. 13, e7142 (2024).

Herrstedt, J. et al. 2023 MASCC and ESMO guideline update for the prevention of chemotherapy-and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. ESMO Open. 102195 (2024).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2024). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf. Accessed September 30.

Drakaki, A. et al. Association of baseline systemic corticosteroid use with overall survival and time to next treatment in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in real-world US oncology practice for advanced non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, or urothelial carcinoma. OncoImmunology. 9, 1824645 (2020).

Aston, W. J. et al. Dexamethasone differentially depletes tumour and peripheral blood lymphocytes and can impact the efficacy of chemotherapy/checkpoint Blockade combination treatment. OncoImmunology. 8, e1641390 (2019).

Johnson, K. C. C. et al. The Immunomodulatory effects of dexamethasone on neoadjuvant chemotherapy for Triple-Negative breast Cancer. Oncol. Ther. 11, 361–374 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Impact of prophylactic dexamethasone on the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors plus platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced Non-Squamous Non-Small-Cell lung cancer. Int. Immunopharmacol. 125, 111138 (2023).

Heinhuis, K. M. et al. Enhancing antitumor response by combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy in solid tumors. Ann. Oncol. 30, 219–235 (2019).

Tieri, J. et al. Tolerability and efficacy of chemoimmunotherapy when administered with a corticosteroid-free anti-emetic regimen. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 29, 1661–1666 (2023).

Yamaguchi, T. et al. Pre-existing pulmonary fibrosis is a risk factor for anti-PD-1-related pneumonitis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective analysis. Lung Cancer. 125, 212–217 (2018).

Dobre, I. A. et al. Outcomes of patients with interstitial lung disease receiving programmed cell death 1 inhibitors: A retrospective case series. Clin. Lung Cancer. 22, e738–e44 (2021).

Laenens, D. et al. Incidence of cardiovascular events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 3430–3438 (2022).

Tison, A. et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitor use in patients with cancer and pre-existing autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 18, 641–656 (2022).

Ding, Z. N. et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibition: systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149, 1993–2008 (2023).

Mao, Z. et al. Effect of concomitant use of analgesics on prognosis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 13 (2022).

Tsikala-Vafea, M., Belani, N., Vieira, K., Khan, H. & Farmakiotis, D. Use of antibiotics is associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 106, 142–154 (2021).

Maslov, D. V. et al. Timing of steroid initiation and response rates to immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer. 9, e002261 (2021).

Fucà, G. et al. Modulation of peripheral blood immune cells by early use of steroids and its association with clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. ESMO Open. 4, e000457 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.P: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, validation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. J.J.: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—Original Draft Preparation. Y.J.K.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing—review and editing. J.-Y.L.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, S.M., Jeong, J., Kim, Y.J. et al. Impact of antiemetic steroid use on survival in small cell lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors and chemotherapy. Sci Rep 15, 22108 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05899-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05899-w