Abstract

Wind turbines are often situated in remote areas under harsh environmental conditions, where external noise and electromagnetic interference can corrupt the data, negatively impacting downstream tasks such as predictive alerts and diagnostics. Consequently, this paper proposes a comprehensive data processing workflow, encompassing both anomaly detection and data interpolation, to preprocess data for wind farms effectively. Firstly, an outlier detection method based on fuzzy voting theory is proposed, utilizing multiple anomaly detectors to ensure accurate detection of outliers within voluminous datasets. Secondly, a multi-segment data interpolation method based on segmented recognition is introduced. This method captures statistical features of the dataset to establish dynamic thresholds for identifying the upper limits of missing segments. For middle gaps, interpolation is performed using forward-backward LOESS, while large gaps are filled using thermal card filling based on similar trend recognition. This approach not only enhances the quality of data interpolation but also optimally balances the training time cost. Finally, the proposed method was validated using real-world wind field data. The results of the analysis demonstrate that compared to LSTM and other interpolation methods, the multi-segment interpolation approach achieved significant improvements in performance metrics, with MAE, MSRE, and RSE reduced by 24%, 7.1%, and 8.2%, respectively, indicating a notable enhancement in data quality. After completing the full data processing workflow, the wind field data showed a substantial improvement in model performance: the test set F1 score of the DLinear model increased by 3.8–19.1%, and Accuracy improved by 2.3–13.3% compared to the unprocessed data. These results highlight the enhanced precision and stability of the early warning model, along with faster convergence speeds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wind power generation, recognized for its clean and renewable energy characteristics, has emerged as a focal point in the global energy sector’s rapid development in recent years. According to a report released by the International Renewable Energy Agency in March 2024, the global capacity for renewable energy installations increased by 510 GW in 2023, with wind energy growing at a rate of 13%, second only to solar energy. The total installed capacity of wind energy reached 1017 GW, and it is expected to continue growing in the future. As the scale of wind power generation continues to expand, the status monitoring and fault prediction of wind turbines have become crucial for ensuring the stability and cost-effectiveness of power systems and wind farms.

Currently, the monitoring and fault prediction of wind turbines primarily employ data-driven approaches, supported by data from Condition Monitoring Systems and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems. These methods involve training models to make predictions based on the collected data1. However, the stability and accuracy of these models heavily depend on continuous and high-quality wind turbine data. In reality, as wind turbines are often located in remote areas and work in harsh environments, sensor failures, external noise, and electromagnetic interference can lead to data corruption or loss during collection, transmission, and storage. This significantly impacts the quality of training data and the analysis and prediction capabilities of the models. Therefore, it is essential to conduct anomaly detection, remove outliers, and perform data imputation to ensure data quality.

Research on anomaly detection in wind turbine data can generally be categorized into two main approaches: statistical-based and machine learning-based methods. Statistical methods include standard deviation, Euclidean distance, and the 3\(\upsigma\) rule, among others. These methods determine whether data deviates from the normal range by assuming that the dataset follows a specific distribution or probability model. This assumption allows for the identification of outliers based on how much a data point strays from the expected parameters of the distribution. Bawanah et al.2 proposed a traffic anomaly detection algorithm based on an improved z-score method, which utilizes occupancy rates. The algorithm identifies anomalies by analyzing road conditions through the detection of significant variations in subsequences within historical occupancy data. The advantages of these statistical-based methods are their simplicity and high speed of execution. However, they typically only consider a few data points around the current sample for analysis. Consequently, when applied to complex and variable data structures such as wind turbine data, traditional statistical methods often fail to capture sufficient information, resulting in inadequate detection accuracy. This limitation highlights the need for more sophisticated techniques capable of handling the intricacies of wind turbine data effectively. Machine learning-based approaches for anomaly detection primarily include methods based on density, distance, clustering, tree-based algorithms, and the currently most researched area, deep learning3. Xiang et al.4 proposed a model called DOIForest, which integrates isolation forest and genetic algorithms. By incorporating two types of mutations and solution strategies, the model optimizes the parameters of the isolation forest, thereby enhancing detection accuracy. De et al.5 introduced a method employing ARIMA and artificial neural networks to predict natural gas consumption. They suggested that significant deviations from the predictions indicate anomalies in gas consumption. Compared to traditional statistical methods, the aforementioned machine learning models generally demonstrate improved accuracy. However, these models require the prior specification of thresholds, which can lead to performance instability when applied to diverse and complex datasets. In recent years, with the advancement of deep neural networks and the rapid development of GPU computing, deep learning techniques have effectively addressed this issue. These techniques can automatically select features and integrate the relationships between them, forming a black-box model6. Common deep learning-based anomaly detection methods include those based on CNN, RNN, GAN, GNN and Transformers7,8,9. These approaches are particularly effective in modeling the intrinsic temporal characteristics of time series data. Munir et al.10 proposed an unsupervised time series anomaly detection method based on a CNN architecture. This method effectively captures the complex linear relationships within time series data and demonstrates strong robustness. Lin et al.11 proposed a hybrid VAE-LSTM model that combines the representation learning capabilities of VAE with the temporal modeling strengths of LSTM networks. This approach captures long-term dependencies within sequences and enables the detection of anomalies across multiple temporal scales. In terms of integrating anomaly detection methods, Wang et al.12 proposed an Autoencoder-based Non-Stationary Pattern Selection Kernel (AE-NPSK), which integrates kernel methods and neural networks by selecting critical edge and internal data from the training set as centers for hidden layer radial basis functions and adaptively adjusting kernel width during training, forming a scalable, reconfigurable, and performance-consistent model structure effectively applied to industrial process monitoring. Deep learning models do not need to design specific thresholds based on different datasets, thereby enhancing generalization capability. However, their complexity may lead to excessively long training times.

Research on data interpolation can also be categorized into two main approaches: statistical and regression-based methods and machine learning-based methods. By extracting statistical features from the dataset and incorporating regression concepts, it is possible to predict and impute missing data. Zhang et al.13 reconstructed complete time series data by integrating the delayed correlation between wind field outputs with a bidirectional weighted ratio approach based on Autoregressive Moving Average (ARMA) models. Sweta et al.14 proposed a method for imputing missing values by utilizing correlation coefficients between variables. The approach selects the variables most strongly correlated with the missing data by calculating the correlation coefficients between the target variable and other variables. The missing values are then predicted using the values of the correlated variables and a linear regression equation. While this method performs well for variables with clear linear relationships, it shows limitations when applied to data with weak or nonlinear correlations. With the development of machine learning technology, using models with strong predictive capabilities for data imputation has become a popular research direction. Bai et al.15 proposed a missing value imputation algorithm based on the MissForest approach. Sánche et al.16 combined regression models and interpolation methods to repair missing wind field data, improving imputation accuracy and robustness. Meanwhile, the effectiveness of regression models may be limited for weakly correlated data. Similarly, in the rapidly evolving field of deep learning within machine learning, Li et al.17 employed LSTM integrated into RNN to impute missing wind turbine power data, enhancing training stability and accuracy. Ju et al.18 proposed an abnormal data recovery framework based on a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) neural network and temporal correlation, optimizing model accuracy through bidirectional prediction, with experiments demonstrating high accuracy and practicality in structural health monitoring. Xin et al.19 introduced a signal recovery method combining Successive Variational Mode Decomposition (SVMD) and TCN–MHA–BiGRU to address continuous missing data in bridge health monitoring systems, exhibiting remarkable capabilities in time-frequency feature extraction and time-series characteristic capture. Deng et al.20 developed an optimized GRU neural network framework with refined input-output configurations and bidirectional prediction, effectively recovering anomalies such as outliers, drift, and missing data in monitoring ancient architectural structures. Hu et al.21 proposed a multiple imputation framework combining GPR and LSTM, which can adapt to complex missing data scenarios. And its high computational complexity may lead to significant resource consumption. In the realm of multi-segment imputation methods, Demirtas et al.22 proposed the MICE (Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations) approach, which iteratively estimates missing values across multiple rounds to enhance data completeness.

This paper addresses the issue of missing SCADA data by proposing a multi-segment interpolation method. Unlike most existing single imputation methods in the literature that are constrained by the complex and variable operating conditions of wind turbines, this method ensures computational efficiency while selectively applying interpolation techniques tailored to the characteristics of missing wind turbine data. To handle the problem of abnormal data in SCADA systems, a detection mechanism based on fuzzy voting theory is designed, which leverages the collaborative operation of multiple anomaly detection models to effectively enhance detection accuracy and generalization ability.

The primary objective of this study is to provide high-quality data support for fault prediction and diagnosis of wind turbines, focusing on common data anomalies such as outliers and missing values. Existing studies typically employ either anomaly detection or data interpolation alone, but relying solely on anomaly detection may compromise data continuity after outlier removal, while depending only on interpolation risks degraded data quality due to residual anomalies. To address these limitations, this paper proposes an integrated workflow, as shown in Fig. 1, that combines anomaly detection and interpolation methods. The process begins with anomaly detection to eliminate outliers, thereby enhancing data usability, followed by targeted interpolation to address both the gaps resulting from outlier removal and the original missing data. This strategy not only improves data quality but also ensures data continuity, ultimately providing effective support for fault prediction and diagnosis tasks.

Data anomaly detection

To effectively identify diverse types of anomalies in datasets, conventional detection methods that rely solely on a single algorithm may fall short. For example, the Isolation Forest algorithm is suitable for detecting global outliers, while the Local Outlier Factor (LOF) is more effective for identifying local outliers. In the harsh operational environments and complex conditions of wind turbines, combined with the challenges of storing large volumes of data, loss and corruption of data during collection, transmission, and storage are inevitable. These factors lead to various types of data anomalies, such as outliers, constant data, stacked data and jumping data.

To more effectively detect the aforementioned types of anomalies, it is advisable to employ a combination of multiple algorithms. However, using a mere sequential approach to detection might encounter two main issues: firstly, the robustness of an algorithm may be significantly compromised when it performs poorly under certain data distributions or noisy environments; secondly, the difficulty in determining the execution order of serial algorithms may lead to the erroneous exclusion of data that is actually normal. Particularly, erroneous removal of data points in the early stages of detection can alter the original distribution of data in subsequent algorithms, triggering a cascade effect that leads to an excessive number of data points being classified as outliers.

Therefore, to enhance the accuracy, stability, and generalization capability of anomaly detection, this paper proposes an integrated anomaly detection method based on fuzzy voting theory. The method is specifically designed to address the complex and variable data loss scenarios that may occur during the collection and storage of wind turbine data, enabling more accurate identification of anomalies.

Define anomaly detectors and affiliation functions

In the process of anomaly detection, this paper employs various detectors to deal with anomalous patterns in the data. For each detector, we utilize a affiliation function to normalize the results of different detection methods to a range of 0 to 1, representing the degree of anomaly of data points.

Outlier detector

Outlier detectors aim to identify points that deviate significantly from the data distribution. This paper employs the Isolation Forest algorithm for this type of anomaly detection. The algorithm begins by randomly drawing subsamples from the dataset. For each subsample, an Isolation Tree is constructed. During the tree construction process, a feature is randomly selected and split at a random value of that feature, until each data point is isolated individually. Subsequently, the average path length for each data point across all isolation trees is calculated23. Finally, the anomaly score is calculated based on the path length; the shorter the path length, the higher the anomaly score. The Sigmoid function is employed as the affiliation function, allowing the anomaly scores from the Isolation Forest to be converted into a smooth membership score. The Sigmoid function is given in equation (1).

where Vo represents the voting score from the outlier detector, and SC is the anomaly score of the data point from the Isolation Forest.

Constant detector

In wind field data, sensor sticking or failure can result in the storage of anomalously unchanging data points over extended periods. This paper addresses such anomalies by calculating the standard deviation within a sliding window of the data. Given a time series data set \(\{x_{1},x_{2},\ldots ,x_{n}\}\) and a window size w ,the ith sliding window is defined as \(\{x_{i},x_{i+1},\ldots ,x_{i+w-1}\}\), where \(1\le i\le n-w+1\). The standard deviation for each sliding window, \(\sigma _{i}\) ,is calculated according to Eq. (2), where \(\mu _{i}\) is the mean of the ith window as shown in Eq. (3). The affiliation function is presented in Eq. (4).

where Th is set as the maximum allowable threshold for constant segments, this paper established at 1e-6. \(V_{C}\) represents the voting score of the constant segment detector.

Stacking detector

The Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) can effectively estimate the dense regions of a data distribution. It assumes that the data are composed of k Gaussian distributions, each with its own mean and covariance matrix. Then the overall probability density function P(x) of the data is given in Eq. (5), where \(\textrm{N}(\textrm{x}|\mu _i,\Sigma _i)\) represents the probability density function of the i-th Gaussian distribution, as calculated in Eq. (6).

where \(w_{i}\) is the mixing weight of the ith Gaussian component, \(\Sigma {i}\) is the covariance matrix of the ith Gaussian component.

where d is the dimension of the data. The affiliation function of the constant segment detector is given in Eq. (7).

where \(V_{P}\) is the voting score of the data stacking detector.

Jump detector

The jump detection problem is modeled as a segmentation optimization problem using the PELT algorithm. The core concept involves dividing the time series data into K segments, each characterized by uniform properties. Significant changes in statistical characteristics are observed at the change-points between segments24.

Dynamic programming recursively optimizes the objective function \(J(\tau _k)\) as shown in Eq. (8), where \(L(S_{K})\) is a function that evaluates the consistency loss of the Kth data segment based on the Radial Basis Function (RBF). The RBF is a nonlinear kernel function as in Eq. (9) When a sudden increase in the loss value \(L(S_{K})\) occurs, the PELT algorithm identifies this point as a potential change-point.

where \(L(S_{K})\) is the subset of data in segment K, \(\beta\) is a regularization parameter to control the number of segments K and prevent overfitting, \(\overline{x}_{k}\) is the intra-segment mean. The Sigmoid function is also chosen for the affiliation function of the data jump detector and its voting score \(V_{J}\) is shown in Eq. (10).

Fuzzy voting

After obtaining the voting outputs from various anomaly detectors, this study integrates the voting results of different detection methods using a fuzzy classifier to produce the final voting result \(V_{J}\). A threshold is then set to determine whether each data point is anomalous. Unlike traditional methods that rely on definite binary outcomes and standard weighted voting for classification, the fuzzy classifier is capable of handling uncertainties. This capability is particularly crucial for managing the complex and variable data from wind turbines. The final fuzzy voting score S is shown in Eq. (11).

where \(i=O,C,P,J\) and \(\omega (i)\) is the fuzzy voting weight. These weights were determined by combining statistical characteristics of wind turbine data with engineering experience. We first analyzed the data characteristics to preliminarily evaluate each detector’s performance for corresponding anomaly types. Based on this analysis, we then adjusted the weights of individual detectors by incorporating practical engineering experience.

Data interpolation

This study proposes a novel data interpolation strategy that combines machine learning techniques with traditional statistical models. By segmenting and imputing wind field data after filtering out anomalies, the proposed method effectively preserves the trends and characteristics of the time-series data while maintaining computational efficiency. Notably, it demonstrates superior interpolation performance in handling the complex and variable missing data scenarios often encountered in wind turbine datasets. Specific programmatic processes:

-

Read the statistical features of the target dataset and set the upper limit of the threshold for each missing segment.

-

All missing segments are categorized into three types: tiny-segment, mid-segment, and large-segment.

-

Different interpolation methods are applied based on the type of missing segments. Linear interpolation is used for tiny-segment; a forward-backward interpolation method based on LOESS (Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing) is used for mid-segment; and a thermal card interpolation method based on similar trend identification is used for large-segment.

Determining the upper limit of the missing segment threshold

Statistical characteristics of the target dataset were analyzed to determine the upper threshold limits for tiny-segment and mid-segment, as shown in Table 1.

For the upper threshold limit of tiny-segment, typically indicative of transient anomalies or noise, this study establishes a direct limit of three. This ensures rapid and accurate identification and resolution of these missing segments.

The primary function of the upper threshold limit for mid-segment is to determine whether to use either a forward-backward interpolation method based on LOESS or a thermal card interpolation method based on similar trend identification. Given that different datasets may exhibit significant variations in missing patterns and proportions, a fixed threshold might not be adaptable to all situations, potentially leading to poor performance in some datasets. Consequently, based on the aforementioned statistical characteristics, this study establishes a dynamic upper threshold limit for moderate missing segments (hereafter referred to as ’the threshold’), which adheres to the following logic:

-

Determine the base threshold by considering the distribution of missing segment proportions across six quartiles: 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 90%. The base threshold is then established by calculating the average of these values.

-

Adjust the threshold based on Percentage of missing P: if P exceeds 20%, the threshold is set by multiplying the base threshold by a correction factor of 1.6; for P between 10% and 20%, the correction factor is 1.4; and for P less than 10%, the correction factor is 1.2.

-

Adjust the threshold based on data skewness , as defined by the skewness formula presented in Equation (12): For absolute \(S_{k}\) greater than 0.95, indicative of extreme skewness, a correction factor of 2.0 is applied for positive skew and 0.5 for negative skew. For absolute \(S_{k}\) between 0.8 and 0.9, considered high skewness, the factors are 1.7 for positive skew and 0.6 for negative skew. For \(S_{k}\) between 0.5 and 0.8, identified as significant skewness, the factors are 1.4 for positive skew and 0.7 for negative skew. For \(S_{k}\) between 0.2 and 0.5, indicating slight skewness, the factors are 1.2 for positive skew and 0.8 for negative skew. For absolute \(L(S_{k})\) less than or equal to 0.2, deemed ’nearly symmetric distribution’, the factor is set at 1.

-

Adjust the threshold based on the proportion of tiny missing segments \(P_{t}\): If Pt exceeds 80%, a correction factor of 1.7 is applied. For Pt between 70% and 80%, the factor is set at 1.4. No adjustment is made for \(P_{t}\) less than 70%.

-

The threshold value obtained by multiplying all the above correction coefficients is limited to the range [4,60], and if it is out of this range, the value closest to the interval is taken.

where \(P_{75}\) and \(P_{25}\) are the 75% and 25% quartiles respectively.

The missing proportion reflects the overall extent of missing values in a dataset and directly influences the choice of interpolation strategies. And the distribution characteristics such as skewness and the proportion of short missing segments measure the asymmetry of data distribution and indicate the tendency of the data to contain extreme values. For instance, by considering skewness, a skewness value of 0.5 (positive skew) indicates a longer tail on the right side of the distribution. This can lead to some longer missing segments. In such cases, it is advisable to increase the threshold to accommodate these longer missing segments, thereby allowing the threshold calculation to adapt to the asymmetry of the data distribution.

The threshold range limit is set at the end to cope with the situation under extreme data. For instance, if there are more than 60 missing data points, this corresponds to over 10 hours of missing data. Experimental evidence indicates that mid-segment interpolation methods begin to distort significantly under these conditions. Therefore, it is advisable to employ large-segment interpolation methods to manage such extensive data gaps effectively.

In conclusion, the combined approach of dynamically adjusting thresholds in conjunction with fixed thresholds can adaptively modify thresholds based on characteristics such as the proportion of missing data and skewness of missingness. This methodology effectively enhances the accuracy and robustness of data interpolation by tailoring the threshold settings to the specific attributes of the dataset.

Mid-segment vacancy interpolation based on forward-backward LOESS

For cases with extended data gaps, the imputed target values often span two distinct characteristics. Traditional imputation models, which typically rely on data from only one side, are prone to distortion25. In this paper, two interpolations, forward and backward, are performed and combined using a local regression fitting model This approach allows the imputation model to ”bridge” the two data segments while simultaneously approximating their respective characteristics, enabling more accurate prediction and imputation.

The target dataset is initially zero-filled and then used to train SARIMA and Prophet (as a backup) models. SARIMA demonstrates strong performance in forecasting and imputing univariate time-series data with trends and seasonality. It is particularly sensitive to periodic features, which align well with the seasonal variations commonly observed in wind turbine data26. On the other hand, the Prophet model, developed by Facebook, is a time-series forecasting tool that emphasizes ease of use and robustness to irregular data, making it a suitable backup model for data imputation27.

Based on the available data at the beginning and end of the missing segments, the trained interpolation models (SARIMA or Prophet) are used to predict the missing values. These models capture the trends, seasonality, and periodicity of the data, providing forward and backward imputed values for the missing segments.

LOESS (Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing) is a non-parametric regression method that estimates the values of unknown points by fitting local data points with weights. The principal concept of LOESS is to perform a weighted regression fit using data points around the target point, assigning higher weights to points closer to the target and lower weights to those farther away. This approach effectively combines both forward and backward interpolation values to enhance model performance.

In this study, LOESS utilizes a form of linear regression as shown in Eq. (13), assessing the fit error through the objective function \(J(\theta )\) of the weighted least squares method, detailed in Eq. (14). This process involves searching for the optimal weighting coefficients that best fit the target point \(x_{0}\). The true value \(y_{i}\) is approximated by the average of forward and backward interpolation values. Additionally, weights are incorporated into the loss function to emphasize data points near the target point. The weight function, which determines each data point’s contribution to the target point, employs a Gaussian kernel, as specified in Eq. (15).

where \(\widehat{y}_{i}\) is the final interpolated value, \(y_{i}^{f}\) is the forward interpolated value, and \(y_{i}^{b}\) is the backward interpolated value, \(\theta _{1}\) and \(\theta _{1}\) is the weighting factor.

where \(x_{0}\) is the target point sampling point location, \(x_{i}\) is the remaining sampling point location, and \(w_i(x_0)\) is a weight function indicating the importance of the data point \((x_{i},y_{i})\) to the predicted point \(x_{0}\).

where \(\tau\) is a bandwidth parameter that controls the rate of weight decay.

Thermal card filling based on similar trend identification

Due to the vast area covered by wind farms, data from different turbines within the same farm may vary significantly under different weather conditions or operational states28. And directly using data from adjacent turbines at the same time may not adequately match the trend of the missing segments. Therefore, this study opts to search for historical data segments from the reference data of adjacent turbines that closely resemble the trend of the missing segment.

The study begins by utilizing a contextual window to extract data immediately before and after the missing segment, from which the slope, mean, and standard deviation are calculated as trend features. Subsequently, the day’s entire reference data for the missing data segment is traversed, employing a sliding window to extract segments of the same length as the missing segment. For each reference segment, its surrounding trend features are computed, and segments with an error within 20% are preserved as candidate interpolation segments. Segments containing missing values in their trend data are excluded. Finally, the collected candidate segments are evaluated for feature similarity to determine the optimal interpolation segment as follows.

Assuming there are M reference segments, each extracting N features, all the features from these segments are combined into an \(M{\times }N\) times matrix R, as shown in Eq. (16). The feature vector t for the context of the missing segment is N-dimensional, as indicated in Eq. (17). The feature weight vector is denoted as \(\omega\), presented in Equation (18), and constructed into a diagonal matrix W as specified in Eq. (19).

Calculate the mean \(\mu _{j}\) and standard deviation \(\sigma _{i}\) for the j-th feature of the reference data. Normalize each element of the reference feature matrix R to \(R_{i.i}^{\prime }\), as shown in Eq. (20), to obtain the normalized reference matrix \({\bf{R}}^{\prime }\), where \(1\le i\le M\),\(1\le j\le N\). Similarly, normalize the target feature vector t to \({\bf{t}}^{\prime }\), as indicated in Eq. (21).

Ultimately, the optimal segment is determined by measuring the similarity between the target data and each reference segment using the weighted Euclidean distance, dist(i), as defined in Eq. (22).

Experiments

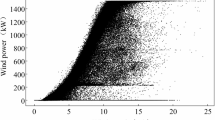

This study validates the practical application effectiveness based on the full-year 2023 SCADA system data obtained from 29 wind turbines at a wind farm in Northeast China. The wind farm comprises two turbine models (W3.X-155 II and W3.X-146 II) with rated power ranging from 3000 to 3450 kW, which demonstrate certain representativeness among wind turbine types. The SCADA system collected data at 10-minute intervals, monitoring 421 operational parameters including rotational speed, temperature, and current, with the operational data covering seasonal variations throughout the entire year.

Taking the gearbox oil temperature data column from 13,824 data points of Turbine 1 in the first quarter of 2023 as an example, the raw data is shown in Fig. 2a. The detection and removal of anomalies using the Isolation Forest algorithm are demonstrated in Fig.2b. It can be observed that the algorithm’s detection of anomalies between sampling points 11,000 and 13,000, which are subject to seasonal variations, is significantly influenced by the seasonal differences in preceding data. This results in an evidently unreasonable detection, exhibiting a ”one-size-fits-all” effect. In addition, the constant abnormal data segment in the magnified portion of Fig.2b was not identified as anomalous. To validate the anomaly detection method based on the fuzzy voting mechanism, a comparison was conducted with sequential detection methods under the same parameters. The resulting anomaly removal effect is shown in Fig.2c, while the effect of the proposed method in this study is illustrated in Fig.2d. Comparing the first three subfigures in Fig.2, it is evident that the proposed method effectively detects a large number of outliers, abrupt change points, and constant segments without causing a chain reaction that leads to the removal of excessive normal data.

To further validate the contributions of each detector, we conducted ablation experiments by sequentially removing each of the four detectors. The results, as shown in Fig. 3, indicate that the overall detection performance significantly declined after the removal of any single detector. Specifically, removing the jump and stacking detectors resulted in a substantial number of false deletions, while eliminating the constant segment detector led to a ”one-size-fits-all” effect similar to that of a single detection algorithm. Conversely, removing the outlier detector caused delays in the timely removal of certain anomalies. Consequently, it can be inferred that the outlier detector contributes significantly to this dataset. Moreover, the consistent performance degradation upon removing any detector demonstrates that each plays an indispensable role in the fuzzy voting mechanism, effectively enhancing the final detection accuracy.

Since it is challenging to definitively determine whether certain data points are true anomalies, the effectiveness of the anomaly detection method cannot be directly quantified using traditional evaluation metrics. Therefore, this study first validates and quantifies the practical application performance of the data supplementation process.

The dataset from the wind farm was analyzed to identify the longest continuous segment of data for a single wind turbine, resulting in a total of 1,069 sampling points for Turbine 1 in 2023. To simulate data loss, random deletion was applied to this dataset. Based on the statistical analysis of the data missing rates for the 29 turbines in 2023, the overall missing rate was approximately 15% to 25%. For this simulation, 200 data points were randomly removed, and the proposed interpolation method was applied to address the missing data in practice.

To determine the upper threshold for missing data segments, the statistical characteristics of the dataset are shown in Table 2. Based on calculations using fixed and dynamic thresholds, the thresholds were determined to be 3 and 15, respectively. Subsequently, multi-segment interpolation was performed. Specifically, linear interpolation was used to fill 100 data points, mid-segment interpolation was used to fill 63 data points, and large-segment was used to fill 37 data points. The final multi-segment interpolation results are shown in Fig. 4b, while the original data distribution is presented in Fig. 4a. In this study, the proposed interpolation approach was compared with various interpolation methods, including the GMM based on statistical principles, KNN and SVR based on machine learning, and LSTM based on deep learning. The interpolation results of the missing data for each method are shown in Fig. 4c–f, with the missing data points highlighted in dark red against the original trend background. It can be observed that the proposed multi-segment interpolation method efficiently handled small missing segments through rapid interpolation, while mid-segment and large-segment were addressed using corresponding effective methods differentiated by dynamic thresholds. Notably, the large-segment interpolation method based on similar trend identification effectively located relevant segments by leveraging the characteristics of the two disconnected sections, achieving superior results.

This study quantifies the effectiveness of the proposed multi-segment imputation using a set of error assessment metrics, including MAE, MSE, RMSE, MAPE, MSRE, and RSE. These conventional metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of the magnitude of errors. For datasets intended for use in deep learning models, this paper introduces additional metrics to further quantify the imputation effectiveness based on overall trend accuracy. These include Trend Deviation Correlation (TDC), Sliding Window Cross-Correlation (SWCC), Relative Trend Preservation Index (RTPI), Event Preservation Level (LEVP), and Variance Fit Score (VFS), which evaluate the preservation of the overall data trend post-imputation. The specific formulas are provided in Eq. (23). It should be noted that the range of the SWCC is between \([-1, 1]\). To align it with the scale of the other metrics, we adjust it using the transformation (SWCC+1)/2. This normalization converts all metrics to the [0, 1] interval, where values closer to 1 indicate better trend preservation.

where the sign function determines the sign of the difference, the corr function represents the calculation of the Pearson correlation coefficient, and the slope function calculates the slope obtained through least squares fitting. extremay denotes local extreme points, the len function is used to count the number of these extreme points, and crossings is a function for calculating the number of times the actual and predicted values cross a certain threshold.

Figure 5a reveals that the multi-segment interpolation method enhances performance by an average of over 20% across all traditional metrics. For instance, the MAE of the model discussed in this paper decreased by 24% to 79.4% compared to the four benchmark models, demonstrating significant suppression of large error spikes. The MSRE decreased by 7.1% to 113.4%, and the RSE by 8.2% to 100.7%. These reductions highlight the superiority of our method in overall error control. According to Fig. 5b, the multi-segment interpolation also outperforms the other four models across all trend-based metrics. For example, the TDC exceeds the other six models by 1.2% to 9.7%. Models such as decision tree regression exhibited greater volatility, indicating a deficiency in the stability essential for interpolation methods. Thus, our interpolation approach demonstrates substantial advantages in multi-dimensional error control and stability compared to the benchmark methods.

The efficiency comparison between the proposed method and the baseline methods is shown in Fig. 6. Although some baseline methods exhibit comparable or slightly faster performance in terms of interpolation time, the proposed method demonstrates superior performance in controlling multi-dimensional errors and ensuring stability. This highlights its ability to strike a balance between computational efficiency and data interpolation quality. Furthermore, the proposed method does not rely on high-performance cloud computing, making it highly suitable for deployment on edge devices. We have directly tested it on systems equipped only with CPUs, and the results indicate that the proposed method maintains excellent feasibility and scalability even in resource-constrained environments.

On one hand, the small data volume in this case study imposes certain limitations on the method described in this paper, particularly for the large-segment interpolation based on similar trend identification, where the advantages are not significantly evident. On the other hand, due to current limitations, it is not feasible to directly quantify the accuracy of the initial anomaly detection segment. Therefore, the overall effectiveness of the data processing workflow is validated using the performance of a fault warning model built for downstream tasks.

To enhance credibility, this study processed the first-quarter data of 29 wind turbines through a complete data flow process, subsequently dividing the dataset into training, validation, and testing sets in an 8:1:1 ratio. The data was then input into a DLinear deep learning model to compare the predictive performance changes on the test set before and after the data processing29. As illustrated in Fig. 7, for turbines 1, 2, and 3, the absolute error loss decreased rapidly with an increase in iterations post-processing. The F1 score improved by 3.8–19.1%, and the accuracy increased by 2.3–13.3% compared to before processing. These results indicate that the warning model, post-complete data processing, is more stable, converges faster, and exhibits significantly enhanced fitting capabilities.

Summary

This article presents a comprehensive data processing framework designed to address anomalies and missing data issues in wind turbine datasets. The framework incorporates an outlier detection method based on fuzzy voting theory and a multi-segment data interpolation approach using segmented recognition.

-

Anomaly detection method based on fuzzy voting theory features four detectors, effectively pinpointing anomalies within large datasets. This method overcomes the limitations of single-method detection, such as over-generalization and missed outliers, and prevents the excessive data exclusion often seen in serial detection approaches.

-

The multi-segment data interpolation method based on segmented recognition first establishes dynamic threshold limits for missing segments based on data statistical characteristics, enhancing generalization across various types and amounts of missing data. The mid-segment interpolation, improved by LOESS, addresses the limitations of traditional models reliant on a single data source, particularly for segments with data discontinuities, thereby ensuring high-quality interpolation. For thermal card filling based on similar trend recognition, the method involves referencing wind turbine data from adjacent time periods and selecting optimal data for extensive filling, effectively minimizing distortion in large-segment interpolation and significantly enhancing data completion quality.

This study effectively addresses various anomalies and missing data within wind turbine datasets, significantly enhancing data quality and generalization capability. This solidifies the foundation for constructing subsequent wind turbine predictive models and implementing forecasting functions.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from CGN New Energy Investment but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of CGN New Energy Investment.

References

Badihi, H., Zhang, Y., Jiang, B., Pillay, P. & Rakheja, S. A comprehensive review on signal-based and model-based condition monitoring of wind turbines: Fault diagnosis and lifetime prognosis. Proc. IEEE 110, 754–806 (2022).

Bawaneh, M. & Simon, V. Anomaly detection in smart city traffic based on time series analysis. In 2019 International Conference on Software, Telecommunications and Computer Networks (SoftCOM). 1–6 (IEEE, 2019).

Xie, L. et al. Review of anomaly detection methods for time series. J. Civ. Aviat. Univ. China 42, 1–12, 18 (2024) (in Chinese).

Xiang, H. et al. Deep optimal isolation forest with genetic algorithm for anomaly detection. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM). 678–687 (IEEE, 2023).

De Nadai, M. & Van Someren, M. Short-term anomaly detection in gas consumption through Arima and artificial neural network forecast. In 2015 IEEE Workshop on Environmental, Energy, and Structural Monitoring Systems (EESMS) Proceedings. 250–255 (IEEE, 2015).

Chuan, S. Imputation of Missing Data from Wind Farms Using Spatio-temporal Correlation and Feature Correlation. Ph.D. thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (2022) (in Chinese).

Li, Z., Liu, F., Yang, W., Peng, S. & Zhou, J. A survey of convolutional neural networks: Analysis, applications, and prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 33, 6999–7019 (2021).

Zamanzadeh Darban, Z., Webb, G. I., Pan, S., Aggarwal, C. & Salehi, M. Deep learning for time series anomaly detection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 57, 1–42 (2024).

Li, G. & Jung, J. J. Deep learning for anomaly detection in multivariate time series: Approaches, applications, and challenges. Inf. Fusion 91, 93–102 (2023).

Munir, M., Siddiqui, S. A., Dengel, A. & Ahmed, S. Deepant: A deep learning approach for unsupervised anomaly detection in time series. IEEE Access 7, 1991–2005 (2018).

Lin, S. et al. Anomaly detection for time series using VAE-LSTM hybrid model. In ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). 4322–4326 (IEEE, 2020).

Wang, K. et al. Anomaly detection using large-scale multimode industrial data: An integration method of nonstationary kernel and autoencoder. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 131, 107839 (2024).

Zhang, D., Li, W., Liu, Y. & Liu, C. A method for reconstructing anomalous active power operation data in wind farms. Power Syst. Autom. 38, 14–18 (2014) ((in Chinese)).

Manna, S. & Pati, S. K. Missing value imputation using correlation coefficient. In Computational Intelligence in Pattern Recognition: Proceedings of CIPR 2020. 551–558 (Springer, 2020).

Bai, H. et al. Missing value imputation for medical big data based on missing forest. J. Jilin Univ. Inf. Sci. Ed. 40, 5 (2022) ((in Chinese)).

Sánchez, C. N., Enriquez-Zarate, J., Velázquez, R., Graff, M. & Sassi, S. Analysis of wind missing data for wind farms in isthmus of tehuantepec. In 2018 IEEE International Autumn Meeting on Power, Electronics and Computing (ROPEC). 1–6 (IEEE, 2018).

Li, T. et al. Fill missing data for wind farms using long short-term memory based recurrent neural network. In 2019 IEEE 3rd International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC). 705–709 (IEEE, 2019).

Ju, H., Deng, Y., Zhai, W. & Li, A. Recovery of abnormal data for bridge structural health monitoring based on deep learning and temporal correlation. Sens. Mater. 34, 4491 (2022).

Xin, J. et al. Recovery method of continuous missing data in the bridge monitoring system using SVMD-assisted TCN-MHA-BIGRU. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2025, 8833186 (2025).

Deng, Y., Ju, H., Li, Y., Hu, Y. & Li, A. Abnormal data recovery of structural health monitoring for ancient city wall using deep learning neural network. Int. J. Architect. Heritage 18, 389–407 (2024).

Hu, Y., Yang, Z. & Hou, W. Multiple receding imputation of time series based on similar conditions screening. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 35, 2837–2846 (2021).

Demirtas, H. Flexible imputation of missing data. J. Stat. Softw. 85, 1–5 (2018).

Wang, R., Nie, F., Wang, Z., He, F. & Li, X. Multiple features and isolation forest-based fast anomaly detector for hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 58, 6664–6676 (2020).

Liu, Z., Lu, W., Wu, J., Yang, S. & Li, G. A pelt-KCN algorithm for FMCW radar interference suppression based on signal reconstruction. IEEE Access 8, 45108–45118 (2020).

Fu, C., Quintana, M., Nagy, Z. & Miller, C. Filling time-series gaps using image techniques: Multidimensional context autoencoder approach for building energy data imputation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 236, 121545 (2024).

Moustafa, S. S. & Khodairy, S. S. Comparison of different predictive models and their effectiveness in sunspot number prediction. Phys. Scr. 98, 045022 (2023).

Al-Ghuwairi, A.-R. et al. Intrusion detection in cloud computing based on time series anomalies utilizing machine learning. J. Cloud Comput. 12, 127 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Li, Y. & Zhang, G. Short-term wind power forecasting approach based on seq2seq model using nwp data. Energy 213, 118371 (2020).

Zeng, A., Chen, M., Zhang, L. & Xu, Q. Are transformers effective for time series forecasting?. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 37, 11121–11128 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and Q.H. conceived the idea, Q.H. conducted the numerical study of the work, all authors took part in analysing the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, Y., Han, Q. & Xue, S. Data anomaly repair method based on fuzzy voting and multi-segment interpolation. Sci Rep 15, 20505 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05951-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05951-9