Abstract

Microalgae attract considerable interest as a source of lipids, carbohydrates, proteins, and high-value compounds, which may be utilized in many sectors, including biofuels, bioplastics, animal feed, and nutraceuticals. There is a great need to improve the cost and efficiency of microalgal processing to advance the feasibility of its large-scale implementation. In this study, we proposed the use of carrot pomace waste to support the heterotrophic cultivation of Auxenochlorella protothecoides using a carrier material to promote attached biomass growth. Various materials were compared for microalgal attached growth, and cotton string was chosen for yielding the highest biomass attachment. String-attached biomass could be harvested easily by straining, and the procedure for direct lipid extraction of attached biomass was optimized, yielding a maximum lipid content of 23.2% DCW. Carrot pomace waste was utilized with a one-time addition of 5 g/L glucose and without mineral supplementation, resulting in a total biomass of 13.2 g/L, of which 98.5% was attached to the string. String-attached biomass had high (49.2%) solid content, making it potentially ready to use. The combination of attached cultivation, heterotrophic conditions, and waste utilization presents a novel microalgal processing scenario with the potential to improve efficiency, reduce costs, and advance overall feasibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microalgae cultivation is studied extensively due to its broad potential across various applications. When cultivated under appropriate conditions, microalgae strains can accumulate a large amount of lipids, carbohydrates, or proteins. Depending on the fatty acid content, microalgal lipids can be an appropriate feedstock for producing biodiesel through transesterification, or for the extraction of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which have health benefits1,2,3. Microalgal carbohydrates can be utilized as a fermentation substrate for generating bioethanol or biohydrogen3,4,5,6,7,8. The high protein content of microalgal biomass makes it a good candidate for animal feed9,10,11. Microalgae can also be utilized for bioplastics production by way of their starch, cellulose, or protein content or through their production of polyhydroxyalkanoates12,13. Furthermore, many strains of microalgae also produce high-value compounds, such as pigments14,15,16, vitamins17,18,19 and antioxidants20,21,22, which can be used in the nutraceutical and cosmetic industries23,24,25,26.

Microalgae are most commonly known for their ability to photosynthesize, converting inorganic carbon (CO2) to microalgal biomass. Alternatively, the ability of several microalgal strains to use organic carbon such as glucose, fructose, or acetate is also well documented27,28. The utilization of inorganic carbon is defined as photoautotrophic, while the use of organic carbon without light is referred to as heterotrophic metabolism. Compared to photoautotrophic conditions, heterotrophic cultivation offers many processing advantages. Photoautotrophic cultivation leads to a phenomenon known as self-shading, where an increase in culture density increases turbidity and decreases light penetration; therefore, the culture eventually limits its own growth29,30. Accordingly, photoautotrophic cultures are generally either implemented in large, shallow, open raceway ponds or photobioreactors. In open systems, there is low areal productivity and high contamination risk, while in closed systems, the capital expenditure and maintenance costs are high31,32,33. In both cases, the availability of CO2 is a growth-limiting factor, and the supply of concentrated CO2 is an added processing cost28,34. In contrast, heterotrophic microalgal culture does not require any light; consequently, standard fermenter equipment can be used. Furthermore, many studies comparing the performance of microalgae in photoautotrophic vs. heterotrophic culture conditions have reported higher biomass and lipid productivity values in the latter condition35,36,37.

One major factor affecting the feasibility of large-scale heterotrophic microalgal cultivation is the cost of the organic carbon38. It is possible to reduce production costs by utilizing wastes or wastewaters as a source of carbon and/or nutrients. Many such cases are reported in the literature39,40,41,42. One study demonstrated that food waste, including rice, meat, and vegetables, could be hydrolyzed and used as a carbon source for the heterotrophic cultivation of the species Chlorella pyrenoidosa and Schizochytrium mangrovei39. As a result, 10–20 g of microalgae biomass was produced using 100 g of dry food waste using stirred and aerated 2 L bioreactors. Guldhe et al.42 (2017) showed the use of aquaculture wastewater for heterotrophic cultivation of Chlorella sorokiniana. They observed dual benefit: (1) a reduction of COD, phosphates, nitrates, and ammonium in the wastewater, potentially enabling its reuse; and (2) a biomass productivity of 498.14 mgL−1d−1, with the potential to be utilized for its carbohydrate, lipid, or protein content in the fields of biofuels or animal feed. The use of “dark fermentation” effluent from hydrogen production was evaluated as a growth medium for the heterotrophic cultivation of microalga C. sorokiniana40. The effluent contained mainly butyrate and acetate, the latter of which was rapidly consumed by the microalga, producing a maximal biomass of 0.33 g/L, demonstrating that waste carbon from the hydrogen production process could be converted to microalgal biomass. Similarly, our previous study established that carrot pomace could be acid-hydrolyzed and used to supplement the heterotrophic culture of A. protothecoides41. Growth medium consisting solely of carrot pomace hydrolysate, referred to as carrot medium (CM), was successfully used to culture A. protothecoides. Additionally, minimal addition of glucose was explored strategically to shift the carbon: nitrogen ratio from 31 to 36 (mol: mol), and this resulted in a higher biomass and lipid output. With CM alone, a maximum biomass and lipid output of 12.9 and 4.9 g/L, respectively, was achieved. With the addition of 5 g/L glucose to the CM, 14.3 g/L biomass and 5.9 g/L lipids were produced. As illustrated, much research has established the possibility of using wastes and wastewaters to improve the prospects of heterotrophic microalgae cultivation.

Attached cultivation is another area of interest concerning microalgal processing due to its potential to improve processing efficiency and cost. Harvesting biomass in suspended cultivation systems requires processing of large volumes of water and is often chemical- or energy-intensive; this can be avoided in attached cultivation systems43,44. Patrinou et al.45 (2020) demonstrated the performance of a bacterial-microalgal consortium in the treatment of poultry waste using photobioreactors tested under suspended and attached-growth conditions45. Higher nutrient removal results were determined for the attached-growth conditions compared to suspended culture, and biomass productivity up to 335.3 mg L−1d−1 was achieved with a maximum lipid content of 19.6%. Gross et al.46 (2013) developed a rotating algal biofilm reactor designed to promote the attached growth of C. vulgaris46. They showed that the attached biomass could be easily manually harvested and had water content similar to that of centrifuged biomass, indicating a simplification and cost savings for harvesting.

The materials that can be used for attached microbial growth should be biocompatible, economical, reusable, and, ideally, should have a large surface area to volume ratio promoting microbial attachment. Mousavian et al.47 (2023) tested jute, cotton, yarn, and nylon as carrier materials for microalgal growth and noted jute and cotton to have higher biomass productivity compared to suspended cultivation47. Shen et al.48 (2016) also demonstrated the successful utilization of cotton rope in an attached microalgal reactor48 – cotton makes for an economical and environmentally friendly material choice. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) hollow fibers were used by Can et al.49 (2021) to support attached growth of a microbial consortium; the material was preferred due to its flexibility, durability, and biocompatibility49. Foam and sponge materials have also been shown to support microalgal attached growth and are known to be economical and reusable50,51,52. Sand grains are well known in marine environments to support attached growth of archaea, bacteria, and microalgae and are also studied in bioreactors53,54,55,56. Sand is resilient and can offer a large surface-to-volume ratio depending on the grain size57. Moving bed biofilm reactors (MBBR) are primarily used for wastewater treatment, where carrier materials are provided in the reactor to support microbial growth and, consequently, the removal of organic load58. MBBR carriers are often constructed of plastic and designed with appropriate geometry and grooves to have a large surface-volume ratio, serving as an economical material for supporting attached biomass growth59. Attached growth is a promising strategy that allows for effective and economical harvesting of biomass60. In this study, we ventured to combine the mentioned conditions – heterotrophic cultivation, attached growth, and waste utilization – to improve the overall feasibility of microalgal biomass and lipid production. Cotton string, PDMS hollow fibers, sponge, reticulated sponge, sand, and plastic biocarriers were tested as materials for attached cultivation of A. protothecoides under heterotrophic conditions. Then, the optimal material was tested for direct lipid extraction of attached biomass and was also evaluated utilizing growth medium formulated using carrot pomace waste.

Results

Biomass attachment on various materials

The amount of biomass attachment achieved with the different materials during the cultivation experiment was compared. Of the 6 materials tested, sand was eliminated from consideration due to the limited attached growth and the difficulties in handling and transferring the material. With an average of 280.7 ± 0.6 mg increase in dry weight, cotton string had significantly higher biomass attachment than all other materials (t-test p value = 0.022 for comparison with sponge, the next highest, Fig. 1a). Accordingly, the suspended biomass of the cultures with added string was significantly lower than the control – 4.2 ± 0.0 vs. 10.5 ± 0.3 g/L (t-test p value = 0.012, Fig. 1b). This outcome was expected; a portion of the biomass was accumulated in attached form, resulting in a reduction in suspended biomass. In contrast, the biocarrier, reticulated sponge (RS) and hollow fiber (HF) groups exhibited low levels of attached biomass, while their suspended biomass values were comparable to that of the control, with no significant difference (ANOVA p value = 0.434). Based on these results, cotton string appeared to be the optimal material for attached microbial growth. Additionally, string has the added advantages of being environmentally friendly, of minimal cost, potentially reusable, and easy to handle and dimension.

(a) Attached and (b) suspended biomass growth of A. protothecoides after 10 days of heterotrophic cultivation with the addition of various materials. RS: reticulated sponge, HF: hollow fiber. *Significantly greater than all other materials (t-test p value = 0.022 for comparison with sponge). **Significantly lower than the control (t-test p value = 0.012).

Direct lipid extraction of attached biomass

Five variations of the lipid extraction procedure were tested in an effort to maximize the lipids that could be recovered from the string-attached biomass samples. Use of the ultrasonic bath alone appears to be the least effective; the lipid content recovered with one and two extraction cycles using the ultrasonic bath (procedures C & D) resulted in only 6.7 ± 0.4 and 9.2 ± 1.2% lipids, respectively. The highest lipid content, 23.2 ± 1.1%, was recovered with procedure A, which involved magnetic stirring of the string and solvent in a 50 °C water bath for 5 h. This outcome was comparable to that achieved by procedures B (19.5 ± 3.3%) and E (22.5 ± 1.3%), with no significant difference (ANOVA p value = 0.519). Therefore, the method of agitation – shaking the bottles versus magnetic stirring – did not appear to influence the outcome, and the use of an ultrasonic bath as a pre-treatment step was found to offer no advantage. Procedures A, B and E were deemed equally effective for direct lipid extraction of string-attached biomass samples.

In addition to testing the string samples, suspended biomass collected from the cultures was also subjected to lipid extraction using the previously described procedure. The lipid content achieved with the extraction of the suspended samples was 38.6 ± 1.3%, which was significantly higher than the lipids recovered with Procedure A, 23.2 ± 1.1% (t-test p value = 0.007). This may be attributed to the attached cells exhibiting different lipid accumulation behavior compared to those in suspension. Since the string absorbs a substantial amount of the carrot medium, it is possible that the cells attached to its surface have greater access to nutrients. Consequently, it may take longer for these attached cells to experience nutrient depletion and to initiate lipid accumulation.

Determining the optimum amount of string for attached growth in carrot medium

The reducing sugar content of the CM was 31 g/L as glucose and based on the total Kjeldahl nitrogen, the C: N ratio (mole per mole) was calculated as 31. The amount of string added to the growth medium was varied to determine whether an optimal quantity could enhance biomass attachment. The amount of biomass that was accumulated in attached and suspended forms for the various conditions was compared (Fig. 2). A slight increase in attached biomass was observed under the 6 g condition compared to the 3 g condition (t-test p value = 0.038). However, there was a steep increase in attached biomass when 12 g of string was used (t-test p value = 0.018 when compared to 6 g). The percentage of attached biomass relative to total biomass increases with the amount of string. The highest ratio of attached biomass, 87.0 ± 2.5%, was achieved under the 12-g string condition, which was significantly higher than the other conditions (t-test p value = 0.016 when compared to 6 g). The total amount of biomass accumulated under the 12-g condition was 1.785 ± 0.039 g, which was significantly higher than that achieved under the 3- and 6-g conditions: 1.266 ± 0.014 and 1.288 ± 0.030 g, respectively (t-test p value = 0.006 for comparison with 6 g). This would indicate that the presence of more string in the carrot medium promoted the culture’s growth in the case of adding 12 g per 100 mL. Note that a higher amount of string (> 12 g/100 mL) was not tested since the string takes up significant volume and eventually exceeds the fluid level.

Biomass accumulated after 10 days heterotrophic cultivation of A. protothecoides using carrot medium with string added for attached biomass growth. Both attached (solid) and suspended (striped) fractions are shown. Either 12, 6 or 3 g of string were added for 100 mL of culture, as labeled. The percentages indicate the fraction of attached: total biomass. *Significantly greater total biomass than the other conditions (t-test p value = 0.006 for comparison with 6 g).

The string samples were extracted directly for lipids. The amount of organic solvent used was proportional to the amount of string-attached biomass in order to provide equivalent extraction conditions. The average amount of lipids extracted was 297 ± 86 mg for the 12-g and 149 ± 9 mg for the 3- and 6-g string groups. When the string samples were extracted for a second round, an additional 12–14% lipids were recovered, with no statistical differences. The relatively low level of lipid recovery from the second round of extraction supports the adequacy of the lipid extraction procedure. Overall, the data show the advantage of using 12 g of string per 100 mL of carrot medium. A higher total amount and attached fraction (87.0%) of biomass was accumulated, which did not need to be harvested with traditional methods used for suspended biomass. Instead, merely straining the string was sufficient to collect the biomass, and after drying, this string-attached biomass could be extracted directly for lipids without any need for separating the biomass from the string.

A general evaluation of cotton string as a material for biomass attachment is that it is easy to handle, economical, and an environmentally friendly choice. Although long-term use means that the string would be periodically renewed, as a waste, it is biodegradable. Our tests indicate that cotton string can withstand multiple cycles of autoclaving and lipid extraction without apparent structural damage. These considerations make it a suitable material for supporting attached growth.

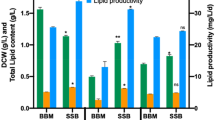

Comparison of growth in carrot medium with and without string

Suspended growth of the cultures in growth medium CM5, with and without string addition, was compared. The control cultures without string (no-string condition) exhibited biomass accumulation as expected, whereas the cultures with added string (string condition) showed minimal suspended growth throughout the experiment (Fig. 3a). This difference could also be observed with the appearance of suspended samples after centrifugation (Fig. 3b). There was hardly any cell pellet collected during the experiment for the string-condition when 5 mL samples were taken.

The attached biomass harvested on day 7 was estimated by deducting the weight of the string used. Accordingly, the average amount of dry string-attached biomass per 100 mL of culture was 1.299 ± 0.003 g, while the dry suspended biomass in these cultures was only 0.020 ± 0.002 g. This indicates that 98.5 ± 0.1% of the total biomass accumulated under the string condition was attached to the string and, consequently, was easily harvested when the string was strained. The total biomass of the cultures (suspended plus attached) under the string condition can be estimated as 13.19 ± 0.01 g/L based on the initial culture volume (100 mL). This was comparable to the biomass achieved under the no-string condition (13.92 ± 0.10 g/L, t-test p value = 0.082). In accordance with a 7-day cultivation period, biomass productivity was estimated to be 1884 and 1989 mgL−1d−1 for the string and no-string conditions, respectively.

Based on wet and dry weights (Eq. 2), the solid content of string-attached biomass samples was 49.2 ± 0.9%, w/w, indicating that the wet biomass attached to the string consisted of 49.2% dry biomass and 50.8% moisture. In contrast, the centrifuged suspended biomass samples from the no-string condition had a significantly lower solid content of 19.6 ± 0.5%, w/w (t-test p value = 0.002). Overall, the prospect of cultivating A. protothecoides in string-attached form offers several advantages, including easy manual harvesting, high biomass recovery (98.5%), and the potential for direct utilization or extraction of the wet, string-attached biomass without the need for a drying step.

Discussion

Our attached growth experiments with A. protothecoides revealed cotton string as the material on which the highest biomass was collected. After testing a number of materials including jute, acrylic and polyester, Christenson and Sims61 also found cotton rope to support the greatest attached growth of mixed culture containing algae and bacteria. They found that after 22 days of cultivation, cotton rope supported 56 g m−2 attached biomass, which was statistically greater than all other materials they tested. Similarly, Lin-Lan et al.62 (2018) showed successful attached growth of Scenedesmus (LX1) on the surface of carriers made using cotton strings. Using a photobioreactor, they demonstrated 0.6–2.7 g m−2 d−1 attached microalgal biomass productivity. Besides being shown to support microalgal attached growth, cotton is also known to be easy to handle, durable, biodegradable, and economical46. A material’s texture and roughness are known to impact biofilm formation63. Cotton string is an effective substrate for attached microalgal growth, likely due to its fibrous structure. The natural twisting of the cotton fibers forms longitudinal grooves along the surface, which increase the available surface area and contribute to surface roughness. Such features can shelter cells from shear forces and improve microbial adhesion strength, yielding robust biofilm formation64.

Patrinou et al.45 (2020) evaluated the use of glass rods supported by a metal grid for attached growth of filamentous cyanobacteria, consisting primarily (ca. 95%) of Leptolyngbya sp., for poultry litter waste treatment and simultaneous lipid accumulation45. The attached biomass was harvested by scraping the rods and had a maximum of 19.6% lipids. Another study comparing different materials showed geotextile as the most preferable for the attached growth of Scenedesmus sp. LX1 and using diluted swine wastewater as the growth medium, they reported a maximum of 29.90% lipid content65. These results are comparable to the maximum lipid content achieved from the string-attached microalgal biomass in our experiments, which was 23.2%. A primary advantage of our experimental setup is that the attached biomass did not need to be “harvested” from the string and could be extracted directly in attached form. The string was noted to be physically intact after lipid extraction and autoclaving, indicating its potential to be reused for another cycle of cultivation.

Another valuable benefit of attached biomass is the high solid content, making it potentially ready to use. Christenson and Sims61 (2012) cultivated their biomass on cotton ropes wound around large spools that were partially submerged and rotated in tertiary wastewater61. With the aid of their automated spool harvester system, they collected biomass with a 12–16% solid content. Alternatively, Johnson and Wen52 (2010) demonstrated the use of polystyrene foam for attached growth in dairy manure wastewater. After manual scraping/harvesting of attached biomass, they reported a water content of 93.75% - indicating a solid content of ca. 6.25%. In contrast, our experiments yielded string-attached biomass with a solid content of 49.2%, w/w, which is significantly higher than the solid content of the suspended biomass collected via centrifugation (19.6%, w/w). The high solid content of the string-attached biomass suggests that it could potentially be used or extracted directly, without the need for drying - thereby eliminating a time- and cost-intensive processing step.

The foremost benefit associated with the attached growth of biomass is the potential to simplify and reduce the cost of harvesting. This harvesting efficiency is strongly dependent on the fraction of biomass attachment. Lin-Lan et al.62 (2018) demonstrated the use of “pom-poms” formed of mohair, linen, or cotton strings for attached cultivation of Scenedesmus LX162. They determined that 10–30% of their total biomass was in the attached phase. In contrast, Lee et al.60 (2014) used nylon mesh with domestic wastewater effluent and compared attached vs. suspended growth in separate raceway ponds. In the pond with mesh material added for attachment, they reported approximately 0 g/m2 suspended biomass after 6 days of cultivation, indicating 100% attached biomass growth. This system achieved greater biomass productivity compared to the authors’ suspended cultivation setup. Our findings are comparable to those of the latter study. We observed 98.5% of the biomass in attached form, with only 1.5% remaining in suspended form after 7 days of cultivation. Another advantage of our experimental setup is that it demonstrates the combination of attached growth with waste utilization, implemented under heterotrophic conditions. Consequently, the biomass productivity achieved under the string condition (1884 mgL−1 d−1) is significantly higher than that reported in photoautotrophic attached growth systems42,45,66.

All the studies mentioned thus far aim to utilize attached growth as a strategy to reduce culture turbidity and overcome the self-shading growth limitation inherent in photoautotrophic microalgal cultures. In contrast, we established the use of attached microalgal cultivation under heterotrophic (no light) conditions. In this way, we showed that the advantages of attached growth can be compounded with those of heterotrophic cultivation, with the potential for scale-up in MBBR-type reactors. Furthermore, the added use of carrot pomace waste to support microalgal growth with only a minimal addition of glucose (5 g/L) indicates a great cost advantage to our proposed process. Overall, the combination of heterotrophic cultivation using organic waste as a carbon and nutrient source, along with string – a cost-effective, biodegradable material – for attached biomass growth offers several advantages. These include the absence of a light requirement, minimal glucose addition, no need for mineral or vitamin supplementation, and simple harvesting of primarily attached biomass with high solid content, which could be readily utilized for its lipid, protein, or carbohydrate content.

Conclusions

The cultivation of the microalga A. protothecoides was successfully demonstrated under heterotrophic (no light) conditions using carrot pomace waste as a carbon and nutrient source, with string added as a support material for attached biomass growth. A total biomass of 13.2 g/L was achieved under the string-added condition, with 98.5% of the biomass collected in attached form, which could be easily harvested by straining the string samples. The string-attached biomass exhibited a solid content of 49.2%, making it potentially ready for use without the need for drying. Furthermore, lipid extraction of the string-attached biomass could be implemented directly, eliminating the need to scrape or remove biomass from the string surface. The combined use of organic waste to support heterotrophic microalgal cultivation in an attached form offers numerous potential benefits, including reduced cultivation and harvesting costs, simpler equipment requirements, and streamlined processing.

Materials and methods

Strain, inoculum, and growth conditions

A. protothecoides (211-10a) was obtained from the Culture Collection of Algae (SAG). The stock culture was maintained on 1.5% agar PM1 medium at room temperature and was subcultured every 2–4 weeks. Synthetic growth medium, PM1, was prepared according to our previous study41. Briefly, PM1 included the following ingredients per liter: 0.7 g KH2PO4, 0.3 g K2HPO4, 0.147 g MgSO4, 25-mg CaCl2∙2H2O, 3-mg FeCl3∙6H2O, 0.1 g glycine, 4 g yeast extract, 0.01-mg vitamin B1, and 1 mL A5 trace mineral solution. All chemicals were either Sigma, Merck, or Isolab brand and of a minimum of 95% purity.

In all experiments, the growth medium was initially inoculated with 5% (v/v) seed culture. Fresh culture on agar medium was used to start the seed (inoculum) cultures, which were cultivated using PM1 plus 10 g/L glucose. The seed cultures were cultivated for 4–5 days prior to use, reaching a biomass content of approximately 4–5 g/L at the time of inoculation. The term “biomass” is used to refer to dry cell weight (DCW). All cultures, including seed cultures, were incubated in the absence of light to ensure heterotrophic metabolism, in an orbital shaking incubator set to 28 °C and 150 rpm, unless noted otherwise67,68. All cultures were cultivated in borosilicate glass bottles, which were sealed with sponge stoppers to allow for air transfer. The bottles were either 100 or 250 mL in volume, with 40% of the volume occupied by the cultures. All experimental conditions were tested with two biological replicates.

Carrot medium preparation

Carrot pomace obtained from the juice producer, GE-TA Tarım (Adana, Turkey), was processed according to Çakır et al.41. Briefly, acid hydrolysis was carried out using 1.1% H2SO4, and a handheld blender was used to facilitate homogenization. The mixture was incubated at 90 °C for 1 h, then cooled, strained with a cheesecloth, neutralized to a pH of 6.5, and autoclaved. Afterwards, the final pH was adjusted to 8.5 using sterile 4 M NaOH solution. The concentration of carrot pomace used was 500 g/L. The described broth was hereafter referred to as carrot medium (CM) and was used for determining the optimum string amount. The total reducing sugar content and total Kjeldahl nitrogen of the CM were determined using DNS69 and standard methods70, respectively. Based on the findings of our previous study, the addition of 5 g/L glucose to the CM was found to promote biomass and lipid production. The 5 g/L glucose was added to the CM prior to autoclaving, and this broth was referred to as CM5 – this was used in the comparison of growth with and without string.

Lipid extraction

The lipid extraction procedure was implemented as described by Çakır et al.41, unless noted otherwise. Briefly, samples were extracted in glass test tubes with chloroform: methanol (1:1). Magnetic stirring was applied at 300 rpm in a water bath set to 50 °C for 5 h. Phase separation was facilitated with the addition of 0.73% aqueous NaCl solution and by centrifugation at 453 g (UNIVERSAL 320 R, Hettich). The chloroform phases containing the extracted lipids were further clarified with an additional centrifugation step, and then transferred to beakers, where the chloroform was volatilized, and the remaining lipids were weighed. The lipids recovered can be compared to the DCW of the sample from which they were extracted to determine lipid content (Eq. 1).

Attached biomass growth on various materials

The purpose of this experiment was to test the tendency of A. protothecoides biomass to grow in attached form on the surface of various materials (Fig. 4). The materials tested for biomass attachment were:

-

Cotton string, about 1 mm in diameter,

-

Polydimethylsiloxane non-porous hollow fibers, 0.3/0.5 mm (ID/OD) (OxyMem Ltd.),

-

Polyurethane sponge,

-

Reticulated polyether sponge with 20 parts per inch holes (Ürosan),

-

Sand with 0.3–0.7 mm diameter grain size, and

-

Polyethylene biocarriers (Bioaqua MBBR, Aquaflex).

String, polyurethane sponge, and sand are commonly available materials that were acquired from local markets. All materials were submerged in water to determine their amount equivalent to 5 mL in volume. Accordingly, a 5 mL equivalent of each material was added per culture. The materials were rinsed with deionized water, oven-dried (100 °C), cooled, and weighed before being placed in 100 mL bottles intended for culturing and were autoclaved together. Synthetic growth medium PM1, containing 30 g/L initial glucose, was prepared and autoclaved. Thirty-eight mL sterile medium and 2 mL seed culture were added aseptically to each bottle. Additionally, control cultures were cultivated with no added materials.

Cultures were cultivated for 10 days in an incubator set to 120 rpm. At the end of the cultivation period all cultures were sampled to determine their biomass content. In the case where materials were tested, the cultures were filtered with a filter set, and light suction was applied. Additionally, the materials were pressed lightly to ensure that any remaining suspended culture would be displaced. The material samples were then transferred to pre-weighed beakers and freeze-dried until constant weight – about 2 days. The final beaker weights and the material samples’ initial weights were used to determine the net attached biomass amount in each case. In addition, the suspended phase of the cultures was sampled, and absorbance at 540 nm (OD540) was measured on a UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Spectroquant® Prove 300, Merck). Samples were diluted such that absorbance values were between 0 and 1; the linearity of measurement in this absorbance range was verified. Actual absorbance values were calculated by accounting for dilution factors. Suspended biomass content was determined based on OD540 measurements using a previously established linear biomass-OD540 correlation, y = 0.144x + 0.746, where y is biomass content in g/L and x is OD540 (R2 = 0.976, valid within the range of 0.2–11.7 g/L).

Direct lipid extraction of attached biomass

The intended purpose of attached microalgal biomass growth was to simplify culture harvesting. With that, the expectation was that the biomass could be extracted for lipids directly in attached form without having to separate the biomass from the string. Accordingly, variations of the lipid extraction procedure were tested to determine how the direct extraction of string-attached biomass could be improved. A. protothecoides was cultivated heterotrophically with synthetic growth medium PM1 containing 30 g/L glucose and string for attachment. Each culture contained four pieces of string, ca. 5 m in length, each weighing 1.172 ± 0.001 g. All strings were placed in methanol in an ultrasonic bath for 15 min to remove any residues that could potentially impact lipid extraction results downstream. They were then rinsed with deionized water and oven-dried before weighing. The cultures were cultivated in 250 mL bottles for 9 days. The string samples were collected with a filter set, strained, and freeze-dried until constant weight, as described. The remaining suspended cultures were measured volumetrically and they were centrifuged, rinsed with deionized water, centrifuged again, and freeze-dried in pre-weighed test tubes. Net dry weights were used to determine the suspended and attached biomass growth of the cultures.

Ten mL of chloroform: methanol (1:1) was added to each string-attached biomass sample, and five variations of the lipid extraction procedure were implemented, as summarized in Table 1. All procedures concluded with phase separation and evaporation of the chloroform phase to determine final lipid weight, as previously described. It should be noted that procedures A and B both retained the samples in a water bath set to 50 °C for 5 h, the only difference being that procedure A had a magnetic stir bar stirring the string-solvent mixture, and in procedure B the bottles containing the mixtures were shaken. In both cases, the purpose of the motion was to increase contact between the string and solvent and to improve the solvent’s diffusion into the cells. The ultrasonic cleaner bath (SK3310HP, Kudos) was operating at a frequency of 53 kHz and ca. 35 °C. Procedure D involved two complete rounds of extraction, meaning that phases were separated – methanol-water phases were discarded, chloroform phases were transferred, and fresh solvent was added to the string samples for the second round of extraction. Finally, procedure E tested the use of procedure C as a pre-treatment for procedure A; phase separation was only conducted at the end of both procedures.

Determining the optimum amount of string for attached growth in Carrot medium

The purpose of this 10-day cultivation experiment was to test the addition of various amounts of string for attached culture growth, to determine what amount would be most appropriate (see schematic in Fig. 5 for experimental protocol). Carrot medium (CM) was prepared with 500 g/L carrot pomace, as previously described. Each condition was tested in 250 mL bottles. The control had no string added, while the others had either 3, 6 or 12 g of string added. The string samples were placed in the culture bottles along with the CM prior to autoclaving so that all components were sterile. The cultures were cultivated for 10 days in an incubator set to 25 °C. At the end of the cultivation term, suspended culture samples were transferred to pre-weighed test tubes, which were centrifuged. The cell pellets were rinsed with deionized water, centrifuged again, and freeze-dried to determine final weights. At the time of harvesting, the volume of suspended culture that remained for each was measured volumetrically and noted. This data was used to determine the amount of biomass that had accumulated in suspended form for each culture. The string samples were collected with a filter set, strained, and freeze-dried until constant weight, as described.

The string-attached biomass samples were extracted for lipids using chloroform: methanol, 1:1. Being the most practical to implement due to the greater amount of string used in this experiment (up to 12 g/100 mL), Procedure B was implemented. That is, string-attached biomass samples were extracted at 50 °C for 5 h in a shaker. The amount of solvent added to the string samples was proportioned based on the amount of attached biomass to provide equal conditions between the groups. Accordingly, the 12, 6, and 3 g string samples were extracted with 100, 54, and 43 mL of solvent, respectively. They were all extracted in 100 mL bottles with tightly sealed caps to avoid solvent evaporation. At the end of the heat treatment, the NaCl solution was added, and the mixtures were thoroughly stirred to ensure contact between all phases. The strings were then left submerged in the solvent-water mixtures overnight, and phases were separated the following day. String samples were thoroughly strained to remove the liquid fractions, which were subsequently centrifuged to achieve phase separation. The chloroform phases were passed through a cotton filter to ensure the removal of any potential solid residues, then transferred to beakers for drying and final weighing of the extracted lipids.

Comparison of growth in carrot medium with and without string

The purpose of this 7-day experiment was to compare the biomass production of A. protothecoides cells cultured heterotrophically in the presence and absence of string. Carrot medium plus 5 g/L glucose (CM5) was used as the growth medium, as previously described. Cultures were cultivated in 250 mL bottles. Strings were washed with deionized water and oven dried before taking final weights. Each piece of string weighed 0.999 ± 0.001 g and was bundled to prevent entanglement during handling and cultivation. Based on previous testing, ca. 12 g of string was added per 100 mL of culture for the attached-growth condition. No string was added to the control cultures. Suspended culture samples were taken, and centrifuged in pre-weighed test tubes to determine biomass content. After 7 days, the remainder of the cultures were harvested, and the strings were thoroughly strained using a 60-mL syringe, which was a practical and effective alternative method for straining. String samples were weighed on the day of harvesting, in “wet” form. Afterwards, the samples were freeze-dried until constant weight, denoted as “dry.” The “wet” and “dry” weight values were used to determine the solid content of the samples (Eq. 2).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using a student’s t-test with unequal variance and one-way ANOVA by assuming normal distribution of data. A p value threshold of 0.05 was used to determine significance. Microsoft Excel was used to conduct the analyses.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kumar, B. R., Deviram, G., Mathimani, T., Duc, P. A. & Pugazhendhi, A. Microalgae as rich source of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 17, 583–588 (2019).

Maltsev, Y. & Maltseva, K. Fatty acids of microalgae: diversity and applications. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 20, 515–547 (2021).

Stansell, G. R., Gray, V. M. & Sym, S. D. Microalgal fatty acid composition: implications for biodiesel quality. J. Appl. Phycol. 24, 791–801 (2012).

Ho, S. H. et al. Bioethanol production using carbohydrate-rich microalgae biomass as feedstock. Bioresour Technol. 135, 191–198 (2013).

Lakatos, G. E. et al. Bioethanol production from microalgae polysaccharides. Folia Microbiol. (Praha). 64, 627–644 (2019).

Lam, M. K. & Lee, K. T. Bioethanol production from microalgae. Handbook Mar. Microalgae 197–208 (2015).

Nagarajan, D., Chang, J. S. & Lee, D. J. Pretreatment of microalgal biomass for efficient biohydrogen production–Recent insights and future perspectives. Bioresour Technol. 302, 122871 (2020).

Chen, C. Y. et al. Microalgae-based carbohydrates for biofuel production. Biochem. Eng. J. 78, 1–10 (2013).

Dineshbabu, G., Goswami, G., Kumar, R., Sinha, A. & Das, D. Microalgae–nutritious, sustainable aqua-and animal feed source. J. Funct. Foods. 62, 103545 (2019).

Nagarajan, D., Varjani, S., Lee, D. J. & Chang, J. S. Sustainable aquaculture and animal feed from microalgae–nutritive value and techno-functional components. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 150, 111549 (2021).

Yaakob, Z., Ali, E., Zainal, A., Mohamad, M. & Takriff, M. S. An overview: biomolecules from microalgae for animal feed and aquaculture. J. Biol. Research-Thessaloniki. 21, 1–10 (2014).

Madadi, R., Maljaee, H., Serafim, L. S. & Ventura, S. P. M. Microalgae as contributors to produce biopolymers. Mar. Drugs. 19, 466 (2021).

Zeller, M. A., Hunt, R., Jones, A. & Sharma, S. Bioplastics and their thermoplastic blends from Spirulina and Chlorella microalgae. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 130, 3263–3275 (2013).

Sun, H. et al. Microalgae-derived pigments for the food industry. Mar. Drugs. 21, 82 (2023).

Ambati, R. R. et al. Industrial potential of carotenoid pigments from microalgae: current trends and future prospects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59, 1880–1902 (2019).

Pagels, F., Salvaterra, D., Amaro, H. M. & Guedes, A. C. Pigments from microalgae. in Handbook of microalgae-based processes and products 465–492 Elsevier, (2020).

Del Mondo, A., Smerilli, A., Sané, E., Sansone, C. & Brunet, C. Challenging microalgal vitamins for human health. Microb. Cell. Fact. 19, 1–23 (2020).

Fabregas, J. & Herrero, C. Vitamin content of four marine microalgae. Potential use as source of vitamins in nutrition. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 5, 259–263 (1990).

Koyande, A. K. et al. Microalgae: A potential alternative to health supplementation for humans. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 8, 16–24 (2019).

Chew, K. W. et al. Microalgae biorefinery: high value products perspectives. Bioresour Technol. 229, 53–62 (2017).

Coulombier, N., Jauffrais, T. & Lebouvier, N. Antioxidant compounds from microalgae: A review. Mar. Drugs. 19, 549 (2021).

Sansone, C. & Brunet, C. Promises and challenges of microalgal antioxidant production. Antioxidants 8, 199 (2019).

Vieira, M. V., Pastrana, L. M. & Fuciños, P. Microalgae encapsulation systems for food, pharmaceutical and cosmetics applications. Mar. Drugs. 18, 644 (2020).

Mourelle, M. L., Gómez, C. P. & Legido, J. L. The potential use of marine microalgae and cyanobacteria in cosmetics and thalassotherapy. Cosmetics 4, 46 (2017).

Puchkova, T., Khapchaeva, S., Zotov, V., Lukyanov, A. & Solovchenko, A. Marine and freshwater microalgae as a sustainable source of cosmeceuticals. Mar. Biol. J. 6, 67–81 (2021).

Castro, V., Oliveira, R. & Dias, A. C. P. Microalgae and cyanobacteria as sources of bioactive compounds for cosmetic applications: A systematic review. Algal Res. 76, 103287 (2023).

Morales-Sánchez, D., Martinez-Rodriguez, O. A., Kyndt, J. & Martinez, A. Heterotrophic growth of microalgae: metabolic aspects. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31, 1–9 (2015).

Abreu, A. P., Morais, R. C., Teixeira, J. A. & Nunes, J. A comparison between microalgal autotrophic growth and metabolite accumulation with heterotrophic, mixotrophic and photoheterotrophic cultivation modes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 159, 112247 (2022).

Saccardo, A., Bezzo, F. & Sforza, E. Microalgae growth in ultra-thin steady-state continuous photobioreactors: assessing self-shading effects. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 977429 (2022).

Jeong, D. & Jang, A. Mitigation of self-shading effect in embedded optical fiber in Chlorella sorokiniana immobilized Polyvinyl alcohol gel beads. Chemosphere 283, 131195 (2021).

Lam, T. P., Lee, T. M., Chen, C. Y. & Chang, J. S. Strategies to control biological contaminants during microalgal cultivation in open ponds. Bioresour Technol. 252, 180–187 (2018).

McBride, R. C. et al. Contamination management in low cost open algae ponds for biofuels production. Ind. Biotechnol. 10, 221–227 (2014).

Marsullo, M. et al. Dynamic modeling of the microalgae cultivation phase for energy production in open raceway ponds and flat panel photobioreactors. Front. Energy Res. 3, 41 (2015).

Seth, J. R. & Wangikar, P. P. Challenges and opportunities for microalgae-mediated CO2 capture and biorefinery. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 112, 1281–1296 (2015).

Barros, A. et al. Heterotrophy as a tool to overcome the long and costly autotrophic scale-up process for large scale production of microalgae. Sci. Rep. 9, 13935 (2019).

Liang, Y., Sarkany, N. & Cui, Y. Biomass and lipid productivities of Chlorella vulgaris under autotrophic, heterotrophic and mixotrophic growth conditions. Biotechnol. Lett. 31, 1043–1049 (2009).

Nicodemou, A., Kallis, M., Agapiou, A., Markidou, A. & Koutinas, M. The effect of trophic modes on biomass and lipid production of five microalgal strains. Water (Basel). 14, 240 (2022).

Silva, T. L., da, Moniz, P., Silva, C. & Reis, A. The role of heterotrophic microalgae in waste conversion to biofuels and bioproducts. Processes 9, 1090 (2021).

Pleissner, D., Lam, W. C., Sun, Z. & Lin, C. S. K. Food waste as nutrient source in heterotrophic microalgae cultivation. Bioresour Technol. 137, 139–146 (2013).

Turon, V., Trably, E., Fayet, A., Fouilland, E. & Steyer, J. P. Raw dark fermentation effluent to support heterotrophic microalgae growth: microalgae successfully outcompete bacteria for acetate. Algal Res. 12, 119–125 (2015).

Çakır, Z. B., Yılmaz, H., Ertan, F., Tanrıseven, A. & Özkan, M. Carrot pomace alone supports heterotrophic growth and lipid production of auxenochlorella protothecoides. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 7315–7327 (2024).

Guldhe, A., Ansari, F. A., Singh, P. & Bux, F. Heterotrophic cultivation of microalgae using aquaculture wastewater: a biorefinery concept for biomass production and nutrient remediation. Ecol. Eng. 99, 47–53 (2017).

Rosli, S. S. et al. Insight review of attached microalgae growth focusing on support material packed in photobioreactor for sustainable biodiesel production and wastewater bioremediation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 134, 110306 (2020).

Wang, J. H. et al. Microalgal attachment and attached systems for biomass production and wastewater treatment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 92, 331–342 (2018).

Patrinou, V. et al. Biotreatment of poultry waste coupled with biodiesel production using suspended and attached growth microalgal-based systems. Sustainability 12, 5024 (2020).

Gross, M., Henry, W., Michael, C. & Wen, Z. Development of a rotating algal biofilm growth system for attached microalgae growth with in situ biomass harvest. Bioresour Technol. 150, 195–201 (2013).

Mousavian, Z. et al. Improving biomass and carbohydrate production of microalgae in the rotating cultivation system on natural carriers. AMB Express. 13, 39 (2023).

Shen, Y., Zhu, W., Chen, C., Nie, Y. & Lin, X. Biofilm formation in attached microalgal reactors. Bioprocess. Biosyst Eng. 39, 1281–1288 (2016).

Can, F., Syron, E. & Ergenekon, P. Effect of gas flow conditions for the treatment of nitric oxide pollutant gas in a Hollow fiber membrane biofilm reactor. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 104600 (2021).

Deantes-Espinosa, V. M. et al. Attached cultivation of Scenedesmus sp. LX1 on selected solids and the effect of surface properties on attachment. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 13, 1–9 (2019).

Singh, G. & Patidar, S. K. Development and applications of attached growth system for microalgae biomass production. Bioenergy Res. 14, 709–722 (2021).

Johnson, M. B. & Wen, Z. Development of an attached microalgal growth system for biofuel production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 525–534 (2010).

Probandt, D., Eickhorst, T., Ellrott, A., Amann, R. & Knittel, K. Microbial life on a sand grain: from bulk sediment to single grains. ISME J. 12, 623–633 (2018).

Nam, T. K., Timmons, M. B., Montemagno, C. D. & Tsukuda, S. M. Biofilm characteristics as affected by sand size and location in fluidized bed vessels. Aquac Eng. 22, 213–224 (2000).

Meadows, P. S. & Anderson, J. G. Micro-organisms attached to marine sand grains. J. Mar. Biol. Association United Kingd. 48, 161–175 (1968).

Ye, S., Sleep, B. E. & Chien, C. The impact of methanogenesis on flow and transport in coarse sand. J. Contam. Hydrol. 103, 48–57 (2009).

Rodgers, M. & Zhan, X. M. Moving-medium biofilm reactors. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2, 213–224 (2003).

Barwal, A. & Chaudhary, R. To study the performance of biocarriers in moving bed biofilm reactor (MBBR) technology and kinetics of biofilm for retrofitting the existing aerobic treatment systems: a review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 13, 285–299 (2014).

Deena, S. R. et al. Efficiency of various biofilm carriers and microbial interactions with substrate in moving bed-biofilm reactor for environmental wastewater treatment. Bioresour Technol. 359, 127421 (2022).

Lee, S. H. et al. Higher biomass productivity of microalgae in an attached growth system, using wastewater. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24, 1566–1573 (2014).

Christenson, L. B. & Sims, R. C. Rotating algal biofilm reactor and spool harvester for wastewater treatment with biofuels by-products. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 109, 1674–1684 (2012).

Lin-Lan, Z., Jing-Han, W. & Hong-Ying, H. Differences between attached and suspended microalgal cells in SsPBR from the perspective of physiological properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol B. 181, 164–169 (2018).

Shen, Y., Zhang, H., Xu, X. & Lin, X. Biofilm formation and lipid accumulation of attached culture of Botryococcus braunii. Bioprocess. Biosyst Eng. 38, 481–488 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. Role of surface roughness in the algal short-term cell adhesion and long-term biofilm cultivation under dynamic flow condition. Algal Res. 46, 101787 (2020).

Zhao, G. et al. Attached cultivation of microalgae on rational carriers for swine wastewater treatment and biomass harvesting. Bioresour Technol. 351, 127014 (2022).

Mohd-Sahib, A. A. et al. Lipid for biodiesel production from attached growth Chlorella vulgaris biomass cultivating in fluidized bed bioreactor packed with polyurethane foam material. Bioresour Technol. 239, 127–136 (2017).

Espinosa-Gonzalez, I., Parashar, A. & Bressler, D. C. Heterotrophic growth and lipid accumulation of Chlorella protothecoides in Whey permeate, a dairy by-product stream, for biofuel production. Bioresour Technol. 155, 170–176 (2014).

Xiong, W., Li, X., Xiang, J. & Wu, Q. High-density fermentation of microalga Chlorella protothecoides in bioreactor for microbio-diesel production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 78, 29–36 (2008).

Miller, G. L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 31, 426–428 (1959).

Federation, W. E. & Association, A. P. H. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. American Public Health Association (APHA): Washington, DC, USA (2005).

Acknowledgements

Carrot pomace was kindly provided by GE-TA Tarım, Adana, Turkey.

Funding

The first author was financially supported by the 100/2000 PhD scholarship program of the Council of Higher Education (YÖK) of Turkey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.B.Ç. was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and writing the original draft of the manuscript. M.Ö. was responsible for acquiring materials and chemicals, providing resources, supervising progress and editing the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Çakır, Z.B., Özkan, M. Implementing heterotrophic attached growth of Auxenochlorella protothecoides using carrot pomace waste for improved microalgal biomass processing efficiency. Sci Rep 15, 21995 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05956-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05956-4