Abstract

Veterinarians often experience burnout and show high suicide rates worldwide, yet today, we lack a scale to assess their work stressors. This study presents the development and validation of the Veterinary Stressors Questionnaire (Vet-SQ), which assesses work stressors in veterinary practice. After 40 interviews with French veterinarians, thirty-two items were selected to describe stressful veterinary situations. French veterinarians then completed an online questionnaire. First data collection stage sampled 3,244 respondents, and the second one, 15 months later, sampled 674. Both questionnaires also contained scales assessing burnout, somatic complaints, sleep problems, suicidal ideations. The Vet-SQ was tested for psychometric properties including longitudinal criterion validity. Eight factors were revealed by the exploratory and confirmatory factorial analyses: workload and work-family conflict, negligence and abuse of some clients towards animals, facing pain and distress, financial worries, conflicts between colleagues, fear of making mistakes, fear of danger and fragmented work. Internal consistency of all the factors was satisfactory (0.70 < α < 0.84). Correlation patterns between all stress factors, burnout variables, somatic complaints, sleep problems, and suicidal ideations supported the criterion-related validity of the scale at both measurements : the Vet-SQ showed satisfactory properties, making it a likely effective tool to assess veterinarians‘ work stressors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Veterinarians play an important social role for animal owners and they are perceived favorably by the public1. However, this role can be impacted by a high risk of poor mental health, which has been observed among this professional group. Indeed, research into the psychological well-being of veterinarians suggests that they are exposed to several psychologically related occupational hazards such as stress, burnout and suicide. In their review of the literature on work-related stress that may affect mental health of veterinarians and including 28 studies from nine countries, Pohl et al.2 stated that “the risks of burnout, anxiety and depressive disorders are higher in this occupational group than in the general population and other occupational groups” (p. 1). Regarding suicide, all the available studies report a high prevalence among veterinarians. For instance, in the USA, deaths by suicide are significantly higher among veterinarians than among general population3,4. According to other studies, veterinarians are twice as likely to commit suicide as other health professionals and three to four times more likely than the general population5,6. Studies in the United Kingdom also showed lower rates of well-being at work for veterinarians compared to other professions7and the proportional rate of suicide mortality was significantly higher compared to doctors8. In Australia, veterinarians showed double proportion of highly distressed respondents that the general population9and suicides rates among veterinarians rose to four times the age-standardized suicide rates of general population10,11.

Identifying the work-related stressors perceived by veterinarians is essential insofar as occupational stressors may be associated with burnout, suicidal ideations and suicide2,12. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to develop and test an instrument assessing the stressors experienced by veterinarians, the Veterinary Stressors Questionnaire (Vet-SQ).

Existing scales

First, we conducted a systematic search of the ScienceDirect, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar databases using the keywords “veterinarians”, “health”, “stress”, “stressors”, and “scale”. This search yielded four scales, although each contains limitations. These scales are presented below.

The veterinary job demands and resources questionnaire

Mastenbroek et al. used the Job Demands-Resources model theoretical framework13 to construct the Veterinary Job Demands and Resources Questionnaire (Vet-DRQ), a scale to assess psychological work environment and personal resources related to work-related wellbeing among veterinarians14.

They conducted semi-structured group interviews with 13 recently graduated veterinarians, allocated to three different groups. As a group, participants were asked to make a list of the most psychologically or physically demanding aspects of their work, and another list of their personal resources and resources of their work. The response categories were listed, and this longlist was then narrowed by 13 participants and by 10 non-participants who had to choose the five most important job demands, job resources and personal resources. This shortlist was then incorporated into a questionnaire completed by 727 veterinarians. Exploratory factor analysis showed seven factors that reflect work demands: Task ambiguity, Workload, Physical demands, Job insecurity, Working circumstances, Work-home interference, and Role conflicts, which align with work psychology literature. By contrast, as specific veterinary stressors have been replaced by the authors by general work stressors in the final form of the questionnaire, factors like fear of mistake, or euthanasia, are absent from the questionnaire. The chosen methodology abstracts the specificity of the stressors met by veterinarians and therefore fails to capture the very nature of their professional stressors, which could lead to misunderstandings and misrepresentations of veterinary professionals’ experiences. Additionally, this scale lacks criterion‑related validity. It also focuses on young professionals, while the authors exclusively targeted veterinarians with less than 10 years of professional experience, resulting in an average age of 32 years (SD = 4.4) for their sample. It therefore excluded a significant part of this professional group since the average age of the French veterinary population is 43 years, with 56% of veterinarians being over 39 years of age, and 84% being above 29 years15.

The burden transfer inventory

Spitznagel et al. developed a scale to determine whether client behaviors contribute to veterinarian stress16. Firstly, the authors conducted a literature review, and surveyed 19 veterinarians to identify stressors, and generate a pool of stressful client interactions. Secondly, this list was tested and enhanced by several small groups of veterinarians. Thirdly, 1,151 veterinarians completed a questionnaire including 33 client-interaction items, along with assessment of stress perception using the Perceived Stress Scale17 and burnout using the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory18. Statistical analysis identified five subscales: daily hassles, non-adherent-inconsiderate, affect, confrontation, and excess communication. However, the authors fail to provide information regarding their analysis, or indices like KMO or Bartlett’s tests to assess the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Additionally, they combined 4 subscales items into 2 new subscales “to improve reliability” (p. 136) but provided no further explanation. In addition, this scale is restricted to stressful client behaviors, while our aim is to include all professional stressors met by veterinarians.

The work stressors among veterinarians in Norway

Dalum et al. investigated the individual and work-related factors associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors among veterinarians in Norway19. To measure work-related factors, they used the Cooper’s Job Stress Questionnaire20 modified by Tyssen21. They also made minor modifications to several items to assure a closer fit to veterinarians’ work conditions, and they added specific items. A principal component analysis identified three job stress factors: emotional demands, (e.g., “Daily contact with dying and critically ill animals”) work/life balance (e.g., “Work affects family life”) and fear of complaints/criticism (e.g., “Worries about complaints from animal owners/customers”). These three categories do not encompass the wide range of stressors met by veterinarians, as the impact of fear of mistakes22or workload23 on veterinarians’ health has been well-documented, among other stressors.

The veterinarian stressors inventory

Among French veterinarians, Andela24 developed the Veterinarian Stressors Inventory (VSI). Interviews (N = 25) were first conducted to collect veterinarian everyday work stressors. A total of 39 items were then selected and included into a questionnaire to assess veterinarians’ stress factors, and explore association with burnout, somatic complaints, and suicidal ideation. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on the questionnaire answers revealed eight stress factors: Work-family conflicts, Tensions with colleagues, Workload, Responsibilities, Financial issues, Emotional demands, Conflicts with clients, and Feeling of danger. The factors correlated significantly with burnout and somatic complaints. Seven out of the eight factors were associated with suicidal ideations. This scale is methodologically sound, while the research design was well-defined, and the statistical methods were appropriate. However, the number of participants is relatively small (N = 490) and the sample included only 10.5% of self-employed and self-employed coworkers while they represent 58.6% of this professional group15. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design of the research (in which data was collected at a single point in time) cannot permit to test predictability of the factors.

With the desire to address the shortcomings of the existing tools, we decided to develop a new scale, paying particular attention to the representativeness of the sample, and the identification of stress factors specific to veterinary practice. We also sought to enhance the validity of the scale by testing its associations with current and future health variables. The aim was to assess specific veterinarian work stressors and to look for associations with burnout and with suicidal ideations, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally.

The present study introduces this tool.

The present study: methods

Study design

First, semi structured individual interviews were conducted with a sample of 40 veterinarians from various practices from December 2019 to June 2020 with the aim of collecting indications of their perceived professional stressors. Participants included 25 veterinarians in private practices and 15 veterinary employees from 27 different French departments (Table 1 provides the sociodemographic information of the interviewees). 22 women and 18 men were interviewed, with an average age of 42.5 years (range 30 to 65 years, SD = 8.9). The interviews were recorded. They lasted 55 min to 2h40 min each (average time: 1h40). An exploratory thematic content analysis was conducted on the interview transcriptions to identify an exhaustive list of items describing work stressors veterinarians encounter in their day-to-day lives. It did confirm most of the themes that had previously been identified by the VSI24. Interestingly, new stress factors also emerged, like experiencing presenteeism, exposure to animal suffering, or challenges related to euthanasia. A list of items was finally selected and discussed with 3 veterinary experts. All of them were practicing veterinarians; two were members of the Social Commission of the Conseil National de l’Ordre (National Order of Veterinarians), and one served on the Vétos-Entraide association board. They contributed to its refinement (comprehension to the target population and unambiguity). The list was then tested for clarity by a sample of 17 veterinary practitioners who were not involved in the study.

The final work stressors scale comprised 32 items (See Table 2), 28 of which were shared with the VSI, with 4 new items added. A Likert scale was used to assess from zero (“never”) to five (“very often”) the frequency with which the participants encountered the situations described by each item.

Sample and settings

All French registered veterinarians were invited by email through the registration board of the Conseil National de l’Ordre to respond to an online questionnaire. A total of 3,244 French veterinarians completed the first questionnaire (17.5% of the working veterinarian population). Women comprised 68.5% of the sample, while men were 31.5%. The average age was 41.5-year-old (range 22 to 77 years, SD = 11.2). The average experience of the respondents was 18 years (range 1 to 51 years, SD = 11.6). The sample included veterinarians with different status: 52% of respondents worked on private practice, while 48% were employees. Veterinarian practice patterns were diverse, as 68% of respondents were companion-animal veterinarians, 21% were mixed practice practitioners (small animals and rural practice), 8% were food-animal veterinarians, and 9% were equine practitioners. This distribution of respondents aligns with that found in the European veterinary census25. A follow-up questionnaire was sent to respondents 15 months later. From these, we obtained 674 responses to the second survey.

Measures

The first questionnaire included questions about demographics, such as age, gender, type of exercise, and the 32 items of the Veterinary Stressors Questionnaire (Vet-SQ). The questionnaire also contained measurements of suicidal ideations, burnout, somatic complaints and sleep problems, in order to investigate the relationship between psychosocial risks, work stress, and their consequences on veterinarians’ health. So that responses could be compared over time, both initial and follow-up questionnaires provided a pairing code, and assessment of suicidal ideations, burnout, somatic complaints and sleep problems of the veterinarians.

(The full questionnaire is available in the OpenScience Framework repository, https://osf.io/efr2p/?view_only=e8ca7ccdc3504b2c933ebcc065e26bd6).

Suicidal ideations

Suicidal ideations were assessed with the three-items scale26 adapted in French by Chabrol and Choquet27. The participants were asked to assess the suicidal ideations they had within the last few weeks if applicable, by the following items: “l felt life was not worth living”, “I felt like hurting myself, " and “I felt like killing myself”. Suicidal ideations score was made by summing the three items scores, ranging from zero (“rarely or none of the time”) to three (“most or all of the time”). Internal consistency was satisfactory for both datasets (αT1 = 0.83 and αT2 = 0.85).

Burnout

Burnout was measured with the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey, which is originally divided into three subscales28 Emotional exhaustion (EE) subscale (five items) evaluates the core symptom of burnout, a higher score of emotional exhaustion indicates high feelings of being emotionally exhausted by one’s work (e.g. “I feel emotionally drained from my work”). Cynicism (Cy) subscale (five items) refers to a detached or negative attitude toward work and people (e.g. “have become less enthusiastic about my work“). Professional efficacy (PE) subscale (six items) assesses lack of confidence about one’s work. Research on burnout theorization showed that PE can be considered as a personal variable close to self-efficacy, rather than a component of burnout29. We therefore chose to focus only on EE and Cy subscales.

Participants were asked to rate from 0 (“never”) to six (“every day”) how often they experienced the described situations. Internal consistency analysis was satisfactory for each subscale at both data collection stages (EE αT1 = 0.94; Cy αT1 = 0.80 and EE αT2 = 0.93; Cy αT2 = 0.82).

Somatic complaints

Somatic complaints were measured with the Psychosomatic Index of the Symptoms Checklist-9030. This scale is composed of a list of 12 body symptoms including headaches, fainting or dizziness sensations, muscle aches, weakness of body parts, arms or legs heaviness.

Veterinarians assessed their somatic complaints rating how they were perturbed by each somatic complaint from one (“not at all”) to four (“very much”). Internal consistency analysis was satisfactory (αT1 = 0.81 and αT2 = 0.81).

Sleep problems

Sleep problems were assessed by the four-items Jenkins Sleep Problems Scale31which evaluates poor sleep quality with items exploring trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, waking up several times a night, and waking up after a usual amount of sleep and still feeling tired and worn out. Participants were asked to rate their sleep problem frequency during the past month from zero (“not at all”) to five (“22 to 31 days”). Internal consistency analysis was satisfactory (αT1 = 0.81 and αT2 = 0.78).

Statistical analyses

The psychometric properties of the work stressors scale were first investigated using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Because there was no reason to assume that the factors were completely independent, and as the distribution of data was normal, we used maximum likelihood method to sort the factors.

To assess the criterion-related validity, we then tested the direct relationships between veterinarian job-stress factors, burnout, somatic complaints, sleep problems and suicidal ideations, with bivariate correlations at the first stage of the data collection (T1) and at the second stage of the data collection (T2).

Results

Construct validity

Exploratory factor analyses

We investigated the psychometric properties of the work stressors scale using both Exploratory and Confirmatory Factorial Analyses (EFA and CFA). Data screening showed that the assumptions of normality were not severely violated (for all factors, -0.81 < Skewness < 0.09 and − 0.75 < Kurtosis < 0.63) Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (0.906) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, χ² (595) = 13 343.12, p < .001 indicated that the correlation matrix was factorable. We divided our sample into two equal datasets to test the factor structure of the scale. A first EFA was conducted on half of the sample (Half dataset, N = 1,622). An eight-factor solution was obtained, accounting for 62.58% of variance, with items loading factors from 0.30 to 0.94. The results of the EFA are set in Table 3.

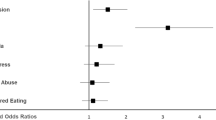

The first factor accounted for 27.50% of total variance and included seven items referring to workload (e.g., “I arrive at the clinic early and I finish my working days late”) and to negative work-home interactions. The second factor accounted for 9.03% of total variance and included five items related to witnessing negligence or abuse from the clients towards their animals, such as “I sometimes see owners who fail in their responsibilities towards their animals”. The third factor accounted for 6.06% of total variance and included five items exploring the facing of pain and distress, with items like “I am affected by animal suffering”. Factor four accounted for 5.08% of variance and was composed of three items referring to the financial worries of respondents (e.g., “I am concerned about the costs of the organization”). Factor five accounted for 4.94% of variance and was composed of three items exploring the conflicts between colleagues, with items like “I have to manage tensions with my colleagues”. Factor six accounted for 3.97% of total variance and included three items referring to fear of making mistakes, such as “I dread making a bad clinical decision”. Factor seven accounted for 3.03% of total variance, and was composed of three factors exploring the fear of being hurt (e.g., “Sometimes I feel in danger during night duties”). Factor eight accounted for 2.99% of total variance, and included three items related to the fragmented work, such as “I am regularly interrupted during my work”.

Confirmatory factor analysis

In accordance with the EFA results, an eight-factor model was tested with Confirmatory Factor Analysis with the second half of the dataset (N = 1,662). The fit indices of the model were satisfactory: χ2 (436) = 4683.4 ; χ2/df = 10.7, RMSEA = 0.05, TLI = 0.89 and CFI = 0.90. The standardized coefficients for CFA were reported on Table 4.

Reliability

The internal consistency of the eight factors of the scale was satisfactory, as all Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.70 to 0.84.

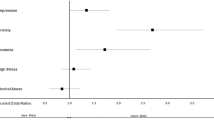

Criterion-related validity

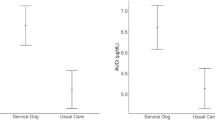

The correlations obtained between the 8 factors of the Vet-SQ and burnout, somatic complaints, sleep problems, and suicidal ideations at the two stages of the data collection (T1 and T2, 15 months later) are presented in Table 5 (N = 660). High scorers on the Vet-SQ were more likely to report experiencing emotional exhaustion, as every correlation remained significant (all p < .001), all r between r = .25 and r = .64, at the first data collection stage, and all r between r = .22 and r = .48, at the second data collection stage. Correlations between the 8 factors of the Vet-SQ and cynicism at T1 and T2 also appeared to be all significant (all p < .001), with all r were between r = .20 and r = .33 at T1, and all r between r = .21 and r = .32 at T2. Work stress assessed by the Vet-SQ and burnout are therefore linked.

Each of the eight factors of the Vet-SQ also correlated positively to somatic complaints (all p < .001), all r between r = .22 and r = .43 at the first data collection stage and all r between r = .25 and r = .39, 15 months later. The eight factors of the scale also correlated positively to sleep problems, (all p < .001) all r between r = .18 and r = .36 at T1 and all r between r = .17 and r = .30 at T2.

The eight factors of the Vet-SQ also correlated positively with suicidal ideations (all p < .001) all r between r = .20 and r = .35 at the first data collection stage and all r between r = .14 and r = .26 after follow-up, giving validity for criterion aspects of the Vet-SQ (Table 5).

Discussion

This study aimed to develop the Vet-SQ, a tool assessing the work stress factors among veterinarians. Presented results provide preliminary evidence of reliability and validity for its eight factors. EFA and CFA of the items showed a similar structure. The number of respondents (N = 3,244) was satisfactory. Analysis showed satisfactory criterion validity, with significant correlations (all p < .001) between work stress factors and burnout, suicidal ideations, somatic complaints and sleep problems initially, and 15 months later (n = 674).

The first factor, Workload and work-life balance reflects somewhat complementary aspects of workload: time amplitude (“I arrive early at the clinic and I finish my working days late”) and amount of work. This factor also includes the issue of work-life balance (e.g., having working hours that impinge on one’s private life). Workload and work-life balance appeared as separated factors in the previous scales of Mastenbroek et al.,14 and Andela24. Note that these stressors are common to a large variety of professions32among which are health care professionals, such as GPs33nurses34physiotherapists35. Workload and arduous working hours, dictated by the profession, tend to limit socialisation with people outside of work, and can thereby contribute to anxiety and depressive disorders for veterinarians36. Weekend and night shifts can also have consequences on private life and family, which impairs the work-home balance.

The second factor refers to the exposition of negligence and abuse of some clients toward their animals. Items such as “witnessing mistreatment by some owners of their animals”, assess to what extent veterinarians may be exposed to unnecessary animal suffering, due to negligence, or animal abuse by clients. Crane’s work demonstrates that suspected pet abuse was a morally significant issue encountered by veterinarians37. Similarly, the item “some clients ask for euthanasia too easily” refers to cases where euthanasia can be requested for client convenience rather than medical reasons, which is ethically complicated for veterinarians38,39. Ethical suffering can also come from being denied the opportunity to care for animals. Negative interactions with clients are directly associated to veterinarian burnout40. The dual loyalty of veterinarians, who must care for animals and also satisfy the owners, can be of major concern in their everyday work39.

The third factor refers to pain and distress encountered by veterinarians, and the diverse emotional demands they have to cope with. It features the exposure to animal end of life and suffering, (“I am affected by animal suffering”) whether due to diseases, age, or iatrogenic pain. Shocking work experience, like suffering and death exposure, which can induce vicarious trauma, has been associated with increasing acquired capability to engage suicidal behaviors among physicians41 and veterinarians42leading to increased suicidal risk43. Emotional demands of veterinarians also imply the psychological difficulty of performing euthanasia (“I am confronted with euthanasia which puts me in difficulty”), even for medical reasons. The complex links between euthanasia and prevalence of suicide risk among veterinarians have been well studied, and contextual factors during euthanasia appear to play a role in its potential protective effects44 or negative impact on suicide risk45,46. Frequency of euthanasia is associated with depression44 and frequency of substance use, excessive drinking, and smoking47. Veterinarians also have to deal with clients’ grief management, and their need for comfort, and empathy, which is particularly challenging when coping with their personal difficulties and emotions48.

The fourth factor refers to financial concerns. Financial concerns have negative effects on mental health5and are linked with sleeping troubles, especially difficulties falling asleep49. Here, it refers to the high costs of care, particularly in maintaining a quality service. Indeed, veterinarians must balance generating enough revenue to ensure good service quality and sustainability of their workplace, with providing affordable bills to clients to be able to care for their animals. Most veterinarians also feel that their salary does not commensurate their efforts at work, as the income are usually estimated unsatisfactory50. Financial worries are associated with lower well-being at work among veterinarians51among a British sample, 39% of doctors who had died by suicide had experienced significant financial problems in the year of the suicide52.

The fifth factor refers to conflicts with colleagues, especially the potential tensions existing in the workplace (“conflicts between some members of the clinic”). Conflicts can arise from different ways of performing work tasks. The financial competition between different veterinary practices also leads to a failed confraternity, deplored by many veterinarians36. Managing tensions with colleagues can be difficult for veterinarians, who are often insufficiently trained in human resources53. Lack of support from colleagues and supervisors is associated with depression54. Conflictual relationship with peers is often cited as a common work-related stress factor among veterinarians5,55,56.

The sixth factor refers to the fear of making mistakes. It is a major concern, especially among young veterinarians56,57. Making a professional mistake is known to provide major psychological impact on young veterinarians’ well-being, leading to lack of confidence, feelings of distress or guilt58. Client complaints are also known to have detrimental effects on psychological distress59. Lack of collegiality and fear of being judged by coworkers may discourage veterinarians of all ages to seek for help in case of doubts at work. Caring for animals entails responsibilities over their lives and health, as well as maintaining a trustful relationship with owners. The fear of making a wrong clinical decision is therefore a major source of professional distress55.

The seventh factor refers to the feeling of being hurt, for example regarding animal-related hazards when veterinarians are providing care (“worry about being injured during interventions”). Veterinarians sometimes have to restrain animals to examine and administer treatment, and the animals can develop defensive and aggressive behaviors, which leads to increased risks of bites and scratches60. In rural medicine, large animals (cattle, horses) can cause serious injury as well. Veterinarians are also exposed to sharp injuries, needles, and wound infections61. The use of various hazardous drug (anesthetics, cytotoxic agents, hormones etc.) also implies a work exposure that can be stressful62. Veterinarians may also face aggressive behaviors from the clients. Working alone, pregnancy, weekend and night shifts, can worsen the feeling of being unsafe at work.

The eighth factor refers to the feeling of being constantly interrupted while working, which leads to a fragmented work (“regularly interrupted during my work”). Interruptions during work are linked to a higher risk of healthcare errors63. To compensate for interruptions, workers usually try to increase their work speed, which involves time pressure, frustration and major effort64. Veterinarians also feel permanently solicited, and they have to deal with animal emergencies. As a result, the pace of their work is irregular and unpredictable, leading to greater stress and increased cognitive load.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to develop a new tool for assessing veterinarian work stress. The scale was built from 40 qualitative veterinarian interviews, in order to understand accurately the specificities of their work-related stress factors. The psychometric properties of the scale were satisfactory. Qualitative analyses sorted the stress factors and revealed their contribution to work stress in veterinarian’s everyday practices. Workload and work-home conflict ranked first place. Being witness to negligence or abuse of some clients towards their animals was the second most stressful factor. Facing pain and distress, and coping with the emotional demands of the practice, appeared to be the third factor. Then, financial concerns, issues with coworkers, fear of making professional mistakes, feeling of being in danger at work, and finally fragmented work, arose. All stressors were linked with burnout, and with past weeks suicidal ideations, which are usually high rates for veterinarians. The stress factors identified also correlate with somatic complaints and sleep problems, and the correlations remained significant 15 months later, which suggests that the stressors assessed play a significant role in understanding the processes at play in veterinary occupational health. This scale, built from a sample that is both sufficiently large and particularly representative of the broader French veterinary population, therefore appears to be a valuable tool for measuring stress factors specific to veterinary practice. Using a relevant stressor scale is a way to understand better their work stressor particularities, but also to elaborate appropriate prevention to enhance veterinarian health at work. Results of the present study therefore contribute to the literature by providing an appropriate tool for both research and professional health prevention.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the OpenScience Framework repository, as well as the questionnaire https://osf.io/efr2p/?view_only=e8ca7ccdc3504b2c933ebcc065e26bd6.

9. References

Kedrowicz, A. A. & Royal, K. D. A comparison of public perceptions of physicians and veterinarians in the united States. Vet. Sci. 7, 50 (2020).

Pohl, R., Botscharow, J., Böckelmann, I. & Thielmann, B. Stress and strain among veterinarians: a scoping review. Ir. Vet. J. 75, 15 (2022).

Miller, J. M. & Beaumont, J. J. Suicide, cancer, and other causes of death among California veterinarians, 1960-1992. Am. J. Ind. Med. 27, 37–49 (1995).

Nett, R. J. et al. Risk factors for suicide, attitudes toward mental illness, and practice-related stressors among US veterinarians. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 247, 945–955 (2015).

Bartram, D. J., Yadegarfar, G. & Baldwin, D. S. Psychosocial working conditions and work-related stressors among UK veterinary surgeons. Occup. Med. 59, 334–341 (2009).

Platt, B., Hawton, K., Simkin, S. & Mellanby, R. J. Systematic review of the prevalence of suicide in veterinary surgeons. Occup. Med. 60, 436–446 (2010).

Johnson, S. et al. The experience of work-related stress across occupations. J. Manag Psychol. 20, 178–187 (2005).

Mellanby, R. Incidence of suicide in the veterinary profession in England and Wales. Vet. Rec. 157, 415 (2005).

Fairnie, H. M. Occupational Injury, Disease and Stress in the Veterinary Profession (Curtin University, 2005).

Jones-Fairnie, H., Ferroni, P., Silburn, S. & Lawrence, D. Suicide in Australian veterinarians. Aust Vet. J. 86, 114–116 (2008).

Milner, A., Niven, H., Page, K. & LaMontagne, A. Suicide in veterinarians and veterinary nurses in australia: 2001–2012. Aust Vet. J. 93, 308–310 (2015).

Milner, A., Witt, K., LaMontagne, A. D. & Niedhammer, I. Authors’ reply: ‘response to: psychosocial job stressors and suicidality: a meta-analysis and systematic review by milner < i > et al’. Occup. Environ. Med. 75, 318–318 (2018).

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F. & Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499 (2001).

Mastenbroek, N. J. J. M. et al. Measuring potential predictors of burnout and engagement among young veterinary professionals; construction of a customised questionnaire (the Vet-DRQ). Vet. Rec. 174, 168–168 (2014).

Conseil National de l’Ordre des Vétérinaires. Atlas Démographique de la Profession Vétérinaire. (2023). https://www.veterinaire.fr/system/files/files/2023-12/ATLAS-NATIONAL-2023%20V07122024.pdf

Spitznagel, M. B., Ben-Porath, Y. S., Rishniw, M., Kogan, L. R. & Carlson, M. D. Development and validation of a burden transfer inventory for predicting veterinarian stress related to client behavior. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 254, 133–144 (2019).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A. Global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 385 (1983).

Kristensen, T. S., Borritz, M., Villadsen, E. & Christensen, K. B. The Copenhagen burnout inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress. 19, 192–207 (2005).

Dalum, H. S., Tyssen, R. & Hem, E. Prevalence and individual and work-related factors associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviours among veterinarians in norway: a cross-sectional, nationwide survey-based study (the NORVET study). BMJ Open. 12, e055827 (2022).

Cooper, C. L., Rout, U. & Faragher, B. Mental health, job satisfaction, and job stress among general practitioners. Manag. Occup. Organ. Stress Res 298, 366–370 (1989).

Tyssen, R., Vaglum, P. & Grùnvold, N. T. The impact of job stress and working conditions on mental health problems among junior house of®cers. A nationwide Norwegian prospective cohort study. (2000). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00540.x

Gibson, J., White, K., Mossop, L., Oxtoby, C. & Brennan, M. We’re gonna end up scared to do anything’: A qualitative exploration of how client complaints are experienced by UK veterinary practitioners. Vet. Rec. 191, e1737 (2022).

Thielmann, B., Pohl, R., Böckelmann, I. & Overcommitment, W. R. Behavior, and Cognitive and Emotional Irritation in Veterinarians: A Comparison of Different Veterinary Working Fields. Healthcare 12, 1514 (2024).

Andela, M. Burnout, somatic complaints, and suicidal ideations among veterinarians: development and validation of the veterinarians stressors inventory. J. Vet. Behav. 37, 48–55 (2020).

Federation of Veterinarians of Europe. Survey of the veterinary profession in Europe 2023. 171 (2023). https://fve.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/FVE-Survey-2023_updated-v3.pdf

Garrison, C. Z., Addy, C. L., Jackson, K. L., McKeown, R. E. & Waller, J. L. The CES-D as a screen for depression and other psychiatric disorders in adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 30, 636–641 (1991).

Chabrol, H. & Choquet, M. Relationship between depressive symptoms, hopelessness and suicidal ideation among 1547 high school students. L’encephale 35, 443–447 (2009).

Schaufeli, W., Leiter, M., Maslach, C. & Jackson, SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory–General Survey. In The MaslachBurnout Inventory–Test Manual (eds. Schaufeli, W., Leiter, M., Maslach, C. & Jackson, SE) 19–26 (ConsultingPsychologists Press., 1996).

Maslach, C., Leiter, M. & Schaufeli, W. Measuring burnout. In: Cooper CL, Cartwright S (eds) The Oxford handbook of organizational well-being. Oxf. Univ. Press Oxf. pp 86–108 (2008).

Derogatis, L. R. & Savitz, K. L. The SCL-90-R, Brief Symptom Inventory, and Matching Clinical Rating Scales. In The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (Ed. M. E. Maruish), (2nd ed., pp. 679–724). (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 1999).

Jenkins, C. D., Stanton, B. A., Niemcryk, S. J. & Rose, R. M. A scale for the Estimation of sleep problems in clinical research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 41, 313–321 (1988).

Siegrist, J. et al. The measurement of effort–reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc. Sci. Med. 58, 1483–1499 (2004).

Karuna, C., Palmer, V., Scott, A. & Gunn, J. Prevalence of burnout among gps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 72, e316–e324 (2022).

Chen, C. & Meier, S. T. Burnout and depression in nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 124, 104099 (2021).

Burri, S. D. et al. Risk factors associated with physical therapist burnout: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 116, 9–24 (2022).

Malvoso, V. Le suicide Dans La profession vétérinaire: étude, gestion et prévention. Bull. Académie Vét Fr. 168, 142–147 (2015).

Crane, M., Phillips, J. & Karin, E. Trait perfectionism strengthens the negative effects of moral stressors occurring in veterinary practice. Aust Vet. J. 93, 354–360 (2015).

Kipperman, B., Morris, P. & Rollin, B. Ethical dilemmas encountered by small animal veterinarians: characterisation, responses, consequences and beliefs regarding euthanasia. Vet. Rec. 182, 548–548 (2018).

Rollin, B. E. Euthanasia, moral stress, and chronic illness in veterinary medicine. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 41, 651–659 (2011).

Rhodes, R. L., Noguchi, K. & Agler, L. M. L. Female veterinarians’ experiences with human clients: the link to burnout and depression. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 15, 572–589 (2022).

Fink-Miller, E. L. Provocative work experiences predict the acquired capability for suicide in physicians. Psychiatry Res. 229, 143–147 (2015).

Fink-Miller, E. L. & Nestler, L. M. Suicide in physicians and veterinarians: risk factors and theories. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 22, 23–26 (2018).

Van Orden, K. A. et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 117, 575 (2010).

Tran, L., Crane, M. F. & Phillips, J. K. The distinct role of performing euthanasia on depression and suicide in veterinarians. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 19, 123 (2014).

Bartram, D. J. & Baldwin, D. S. Veterinary surgeons and suicide: a structured review of possible influences on increased risk. Vet. Rec. 166, 388–397 (2010).

Witte, T. K., Correia, C. J. & Angarano, D. Experience with euthanasia is associated with fearlessness about death in veterinary students. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 43, 125–138 (2013).

Reeve, C. L., Rogelberg, S. G., Spitzmüller, C. & DiGiacomo, N. The Caring-Killing paradox: Euthanasia‐Related strain among Animal‐Shelter workers 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 35, 119–143 (2005).

Morris, P. Managing pet owners’ guilt and grief in veterinary euthanasia encounters. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 41, 337–365 (2012).

Torrès, O. & Thurik, R. Small business owners and health. Small Bus. Econ. 53, 311–321 (2019).

Cake, M. A., Bell, M. A., Bickley, N. & Bartram, D. J. The life of meaning: a model of the positive contributions to well-being from veterinary work. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 42, 184–193 (2015).

Wallace, J. E. Meaningful work and well-being: a study of the positive side of veterinary work. Vet. Rec. 185, 571–571 (2019).

Hawton, K., Malmberg, A. & Simkin, S. Suicide in doctors: A psychological autopsy study. J. Psychosom. Res. 57, 1–4 (2004).

Moses, L., Malowney, M. J. & Wesley Boyd, J. Ethical conflict and moral distress in veterinary practice: A survey of North American veterinarians. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 32, 2115–2122 (2018).

Waldenström, K. et al. Externally assessed psychosocial work characteristics and diagnoses of anxiety and depression. Occup. Environ. Med. 65, 90 (2008).

VandeGriek, O. H. et al. Development of a taxonomy of practice-related stressors experienced by veterinarians in the united States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 252, 227–233 (2018).

Stoewen, D. L. Suicide in veterinary medicine: let’s talk about it. Can. Vet. J. 56, 89 (2015).

Gardner, D. & Hini, D. Work-related stress in the veterinary profession in new Zealand. N Z. Vet. J. 54, 119–124 (2006).

Mellanby, R. & Herrtage, M. Survey of mistakes made by recent veterinary graduates. Vet. Rec. 155, 761–765 (2004).

Bryce, A. R. et al. Effect of client complaints on small animal veterinary internists. J. Small Anim. Pract. 60, 167–172 (2019).

Johnson, L. & Fritschi, L. Frequency of workplace incidents and injuries in veterinarians, veterinary nurses and veterinary students and measures to control these. Aust Vet. J. 102, 431–439 (2024).

Jeyaretnam, J., Jones, H. & Phillips, M. Disease and injury among veterinarians. Aust Vet. J. 78, 625–629 (2000).

Gibbins, J. D. & MacMahon, K. Workplace safety and health for the veterinary health care team. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 45, 409–426 (2015).

Monteiro, C., Avelar, A. F. M. & Pedreira, M. D. L. G. Interruptions of nurses’ activities and patient safety: an integrative literature review. Rev. Lat Am. Enfermagem. 23, 169–179 (2015).

Mark, G., Gudith, D. & Klocke, U. The cost of interrupted work: more speed and stress. In Proceedings of the SIGCHIconference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (eds. Mark, G., Gudith, D. & Klocke, U.) 107–110 (2008).

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Ordre National des Vétérinaires, (National Order of Veterinarians) and by Vétos-Entraide. The authors would like to express their thanks to the members of the board of the Order, in particular Corinne Bisbarre, head of the social commission, and Jacques Guérin, the president, and to Vétos-Entraide, in particular Joëlle Thiesset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M, M.A and D.T contributed to the study conception and design. A.M and D.T wrote the main manuscript text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was provided, and APA ethical standards were followed in the conduct of the study. All procedures complied with latest version of the Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mudry, A., Truchot, D. & Andela, M. Development and longitudinal validation of the Veterinary Stressors Questionnaire. Sci Rep 15, 21846 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05965-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05965-3