Abstract

As population aging accelerates in China, community care services have become increasingly important for supporting the well-being of older adults. However, research examining gender-specific associations between community care services and quality of life (QoL) remains limited. This study aimed to investigate the gender-specific associations between the perceived availability of community care services and QoL among older adults, using data from the eighth wave (2017–2018) of the China Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS). Multivariable linear regression models stratified by gender were employed to examine the associations between eight types of community care services and self-reported QoL, adjusting for potential confounders. A total of 8657 participants aged 65 years and older were included in the final analysis. The results indicated significant gender differences: among older men, the perceived availability of personal care services was positively associated with better QoL scores (β = 0.132, P = 0.010), whereas among older women, the perceived availability of healthcare education services was positively associated with better QoL scores (β = 0.053, P = 0.020). These findings suggest that gender-specific patterns exist in the associations between community care services and QoL, underscoring the need to tailor community care strategies to the distinct needs of older men and women. Overall, this study provides empirical evidence supporting the importance of community care services in promoting the well-being of the aging population in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As populations age around the world, the number of adults over 60 years old has grown rapidly, from 810 million in 2012 to 1 billion in 20191. The World Health Organization (WHO) expects the aging trend to accelerate, with the number of older adults increasing to 1.4 billion by the 2030s2. China has the largest older adult population in the world3, with more than 200 million older adults in 2021 (14.2% of the total population)4, projected to increase to 400 million by 2050 (26.9% of the total population)5. This demographic shift not only increases the volume of care needed but also diversifies the types of care services required, reflecting the increasingly complex physical, psychological, and social needs of the aging population6. Physically, many older adults face a growing burden of chronic diseases, functional decline, and mobility limitations7, creating demand for health education, preventive healthcare, rehabilitation, and personal daily care services6,7. Psychologically, older adults are more vulnerable to depression, cognitive impairment, and emotional distress, underscoring the need for psychological consulting and mental health support8. Socially, the gradual weakening of traditional family-based support systems has contributed to an increasing need for supportive services that help older adults maintain daily functioning and social participation9,10. As intergenerational caregiving resources become less readily available, there is a growing demand for community-based initiatives such as home visit services, daily shopping assistance, social and recreational activities, and programs that promote neighboring relationships, aiming to strengthen social ties and support independent living11. Thus, developing comprehensive and accessible community care services has become a critical strategy to support the well-being of older adults.

Beginning in 2016, China launched the Home and Community Care Services Reform Pilot, aiming to develop a comprehensive, accessible, and diversified community care system12. The reform pilot focused on expanding community-based quality care services for older adults13, encompassing medical services, life management support, psychological consulting, cultural and recreational activities, regulatory guidance14. Specific initiatives included home visit services, health education programs, personal daily care services, daily shopping assistance, psychological counseling, social and recreational activities, and programs to strengthen neighboring relationships14. Since its initiation, the pilot program has undergone five rounds of expansion and by 2023 had extended to 203 localities across all provinces and municipalities in China15. As the availability and accessibility of community-based services have improved, older adults have increasingly accessed and utilized these services16,17. According to the Basic Data Bulletin of the Fifth Sample Survey on the Living Conditions of Older Adults in China, released in October 2024, more than 60% of older adults reported being satisfied with community-based health and older adult care services18. This high level of satisfaction indicates that community care services are playing an increasingly important role in promoting healthy and active aging.

Although community-based services have expanded nationwide and pilot programs have been widely implemented, community care in China remains at an early stage of institutional development19. Although the reform pilot expanded community care services nationwide, variations remain in the actual scope, quality, and comprehensiveness of service delivery across regions17. This is primarily because community care initiatives are still undergoing regional adjustments, and a unified, standardized framework has yet to be established11,17. In contrast, countries such as Japan and South Korea have developed mature community care systems characterized by clearly defined service standards, integrated medical and social support, and consistent quality management20. In China, the absence of nationally standardized definitions and protocols has resulted in substantial regional variations in service scope and quality11,17. Economically developed cities such as Shanghai and Beijing offer a diverse range of community-based services21, while less affluent regions, including some western provinces, often provide only basic home visit services and daily living assistance, constrained by fiscal and administrative resources22. These regional disparities in service provision highlight the need to further characterize and evaluate the types and functions of community care services available to older adults.

Research has shown that access to community care services affects the health of older adults. Among older adults in China, the incidence of depression has increased23, life satisfaction is declining24, and suicide is occurring more frequently25, leading to a decline in QoL. Studies have reported that access to community care services can reduce the risk of loneliness26 and depression27, increase life satisfaction28,29, and improve mental health30 and self-reported health28,30,31. However, other studies have reported less favorable findings, indicating that inadequate or poorly coordinated community care services can exacerbate psychological distress, contribute to unmet healthcare needs, and impair overall well-being11,32. In light of these mixed results, conducting empirical analyses during China’s ongoing pilot phase is essential to provide an evidence base for the future standardization and refinement of community-based care services. In addition, given that QoL has become a central objective of healthy aging initiatives worldwide33, it has likewise been firmly established as a critical goal within China’s strategies for promoting successful aging34. Unlike disease-specific or function-specific health outcomes, QoL represents a comprehensive, multidimensional construct that reflects older adults’ physical, psychological, and social well-being35. As such, QoL provides an integrative assessment of how community care services influence overall well-being beyond isolated clinical or functional measures. Understanding the associations between different types of community care services and older adults’ QoL is of critical policy relevance. Empirical research clarifying how specific services relate to self-perceived QoL can help policymakers prioritize and refine community care strategies to better support the well-being of the aging population.

Moreover, gender differences in aging trajectories further complicate the landscape of care needs among older adults. Research consistently shows that older men and women differ significantly across multiple dimensions, including physical health, psychological well-being, social support networks, and service preferences36,37. Physiologically, women tend to live longer than men but experience a greater burden of disability, chronic pain, and functional limitations in later life38, whereas men often have higher mortality rates from cardiovascular and metabolic diseases but shorter overall life expectancy39. Psychologically, older women are more prone to depression, anxiety, and feelings of loneliness40, while older men, despite reporting fewer emotional symptoms, face higher risks of social isolation and under-diagnosed mental health issues41. In terms of social and economic resources, older women generally have broader social networks but fewer financial assets, partly due to historical disparities in labor market participation and pension entitlements11,42. In contrast, older men often maintain greater economic independence but may lack robust social support systems after retirement or widowhood43. These differences translate into distinct patterns of caregiving expectations and service utilization: women are more likely to prioritize emotional support, health education, and social engagement services, whereas men tend to emphasize instrumental assistance, physical rehabilitation, and disease management44. Ignoring these gender-specific needs risks designing community care programs that inadequately address the heterogeneous realities of the aging population.

Overall, previous research has provided valuable insights into the general effects of community care services; however, relatively few studies have differentiated between specific service types. Moreover, existing research has documented significant gender differences across physical health, psychological well-being, social resources, and service preferences among older adults, highlighting the importance of incorporating gender-specific analyses. Thus, this study investigates the associations between eight types of community care services—personal care services, home visit services, psychological consulting services, daily shopping assistance, social and recreational activities, legal aid services, healthcare education services, and neighborhood-relation support—and self-reported QoL among older adults in China, with stratified analyses by gender. These service components were selected because they collectively address the multifaceted needs of older adults, including physical assistance (e.g., personal care, home visits), psychological support (e.g., psychological consulting, social and recreational activities), and social participation and protection (e.g., daily shopping assistance, legal aid services, neighborhood-relation support). This classification also aligns with the core service domains emphasized in China’s Home and Community Care Services Reform Pilot, reflecting national priorities in building a comprehensive and responsive community care system. By examining specific service types and exploring gender-specific patterns, this study aims to generate detailed empirical evidence to inform the targeted refinement and standardization of community care strategies, supporting evidence-based policy development for healthy aging in a rapidly aging society.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study utilized cross-sectional data from the eighth wave (2017–2018) of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) to examine the associations between community care services and QoL among older adults, with analyses stratified by gender. The CLHLS has been conducted every three years since 1998 by the Centre for Healthy Ageing and Development Studies at Peking University. The survey takes a random sample of individuals aged 65 years and older, as well as their children, from several counties/cities in 22 of the 31 provinces and Chenmai County in Hainan Province, China45. This sample represents approximately half the Chinese population. The CLHLS data are particularly valuable for this study as this is the only survey on older adult community care in China. This study was conducted after receiving a KUIRB-2023-0151-01 exemption from the Korea University Institutional Review Board. Notably, this study relied solely on pre-existing data and documents, without collecting any new information from research participants.

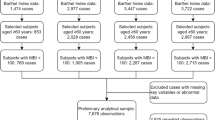

Initially, the participant cohort was composed of 15,737 individuals from the 2018 CLHLS database. After excluding those with incomplete data on QoL, community care services, and other covariates, the analytical cohort was narrowed down to 8,657 individuals, and the sample selection process is detailed in Fig. 1. This final study group included 3,550 older men and 5,107 older women.

Assessment of self-reported QoL

The dependent variable in this study is the self-reported QoL among older adults, representing a subjective state of well-being specific to each individual. QoL was measured using the question, “How do you rate your life at the moment?” from the CLHLS dataset, where lower values indicate better perceived QoL. In the analysis, this self-reported QoL measure was treated as a continuous variable, where lower scores reflected a more favorable self-perception of quality of life, allowing for a detailed examination of its relationship with various factors under study.

Assessment of perceived availability of community care services

Community care was measured using the question, “What kind of social services are available in your community?” In the CLHLS survey, these items reflect the perceived availability of services, not actual utilization. Community care was divided into eight areas: (1) home visit services, (2) health education, (3) personal daily care services, (4) daily shopping, (5) psychological consulting, (6) social and recreational activities, (7) health education, and (8) neighboring relationships. For each type of community care, we defined (1) “yes” as available and (2) “no” as unavailable.

Control variables

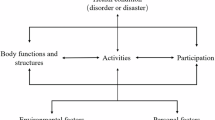

The control variables were based on Andersen’s46 expanded behavioral model of health service use. Accordingly, three types of factors were classified: predisposing, enabling, and need.

Predisposing factors included demographic factors, such as age, education, and marital status. “Current age” determined the age of the respondent. “How many years did you attend school”? was asked to determine the years of schooling. “Current marital status” defined the current presence or absence of a spouse, with (1) “married and living with spouse” and (2) “married but not living with spouse” indicating the presence of a spouse, and (3) “divorced,” (4) “widowed,” and (5) “never married” indicating the absence of a spouse.

The enabling factors include the number of children, residence, residence status, self-perceived economic status, and public old-age pension status. “How many children, including those who have died, do or did you have?” was used to determine the number of children. “Current residence area of interviewee” was used to determine the respondent’s residence, wherein (1) “city” and (2) “town” were defined as urban and (3) “rural” as rural. Residential status was divided into “living with family” and “living alone.” Self-perceived economic status was divided into three groups: (1) “good,” (2) “average,” and (3) “poor.” Public old-age insurance was divided into “yes” and “no.”

The need factors include self-perceived health status and ADL limitations. “How do you feel about your health on a typical day?” was asked to determine self-perceived health, which was categorized on a five-point scale: (1) “very good,” (2) “good,” (3) “average,” (4) “poor,” and (5) “very poor.” The presence of an ADL limitation was determined based on six domains: bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence, and eating. Respondents who reported difficulty in any one of these six activities were categorized as having an ADL limitation (“yes”), while those reporting no difficulty in all six activities were categorized as having no ADL limitation (“no”).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 and R software version 4.4.1. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a significance threshold set at 0.05. The following analysis methods were applied: initially, we compared the sample characteristics between men and women using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Subsequently, we employed multivariable linear regression models, stratified by gender, to investigate the relationship between community care services and QoL among older men and older women. Gender stratification was pre-specified based on theoretical and empirical evidence suggesting significant differences in health status, psychosocial factors, and service utilization patterns between older men and women. The results were reported as beta coefficients (β) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to assess potential gender differences in this relationship.

We developed four models to control for confounding factors. In all models, the eight types of community care services were included concurrently as independent variables to estimate their independent associations with QoL. In these models, community care services were treated as the independent variable. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 adjusted for predisposing factors, including age, education, and marital status. Model 3 further adjusted for enabling factors, such as the number of children, residence, residence status, self-perceived economic status, and public old-age pension status. Model 4 (the fully adjusted model) additionally accounted for need factors, including self-perceived health status and ADL limitations. We calculated variance inflation factor (VIF) values among all variables included in the regression models to assess potential multicollinearity. A VIF value below 5 is generally considered acceptable, indicating no significant multicollinearity and supporting the stability and interpretability of the models. The VIF values for the eight community care service items were all below 2 in both the male and female models, suggesting minimal multicollinearity among the primary exposure variables.

Results

Sample characteristics of the participants

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the participants. The average QoL of the 8,657 participants was 2.13 ± 0.794. As seen in Table 1, the women surveyed had an average age that was older than the men surveyed. Older women tended to have more children and choose to live with family more often. They also had fewer years of education, poorer subjective economic and health status, less pension insurance, and greater barriers to ADLs. There were no significant gender differences in QoL, the perceived availability of community care services, or place of residence.

Association between perceived availability of community care services and QoL among older men

Table 2 presents the associations between the perceived availability of community care services and QoL among older men, based on multivariable linear regression models. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values for all covariates ranged from 1.026 to 1.761, indicating no serious multicollinearity. Focusing on the fully adjusted Model 4, the perceived availability of personal care services was significantly associated with better QoL scores (β = 0.132, 95% CI 0.031–0.232; see Fig. 2). Additionally, residential status, self-perceived economic status, self-perceived health status, and absence of ADL limitations were positively associated with better QoL, while older age was associated with worse QoL among older men.

Association between perceived availability of community care services and QoL among older women

Table 3 presents the associations between the perceived availability of community care services and QoL among older women. The VIF values for all covariates ranged from 1.039 to 1.938, indicating no serious multicollinearity. In the fully adjusted Model 4, the perceived availability of healthcare education services was significantly associated with better QoL scores (β = 0.053, 95% CI 0.008–0.098; see Fig. 3). Moreover, residential status, self-perceived economic status, self-perceived health status, and receipt of public old-age insurance were positively associated with better QoL, whereas a higher number of years of education was associated with worse QoL among older women.

Discussion

The demand for older adult care in China is increasing due to population aging and shrinking family sizes. To develop effective older adult care policies, it is necessary to examine how community care services are associated with QoL, both by service type and by gender. Therefore, this study investigated the associations between the perceived availability of community care services and the QoL of Chinese adults aged 65 years or older, with analyses stratified by gender. In this study, gender-stratified analyses were pre-specified based on substantial theoretical and empirical evidence. This approach allowed us to explore independent association patterns within each gender group, providing a more nuanced understanding of the linkages between the perceived availability of community care services and QoL. Our findings suggest that community care services associated with QoL differ between older men and older women, highlighting the importance of developing policies that recognize gender-specific needs and challenges among older adults.

The results showed that, among older men, the perceived availability of personal care services was associated with better QoL scores. This association may reflect traditional gender roles and the specific nature of aging experiences among older men in China. Gender roles in China have historically evolved along the life course: men were typically positioned as heads of households and primary economic providers, while women assumed responsibilities related to caregiving and domestic work. After retirement, older men often encounter a reduction in social roles and participation, which has been linked to lower levels of well-being47. In this context, the availability of personal care services—such as assistance with laundry and daily activities—may help older men maintain independence and daily functioning, which could be associated with better perceived QoL compared to women47. Supporting this interpretation, Xia19 reported that personal care services had the lowest provision rate (9.3%) among the eight community care items examined. Although China has expanded community-based elder support and nursing facility capacity, the supply of personal care services remains relatively limited48. Given these observations, understanding the service needs of older men and expanding the availability of personal care services may be important for supporting their daily living needs and enhancing perceived well-being.

Although only the perceived availability of personal care services was significantly associated with better QoL scores among men, several other services—including home visit services, psychological consulting, health education, and neighboring relationships—also showed positive but non-significant associations. These results suggest that various forms of community care may be relevant to men’s QoL, though their effectiveness might be limited by factors such as inconsistent implementation, variability in service quality, or cultural norms that reduce engagement—particularly with emotionally oriented services. In contrast, daily shopping assistance, social and recreational activities, and health education were negatively associated with QoL, potentially reflecting a mismatch between service content and men’s preferences, or a tendency for men with poorer health or limited social integration to be more aware of or reliant on these services.

Among older women, the perceived availability of healthcare education services was associated with better QoL scores. This association may reflect educational disparities observed among older cohorts in China. Prior research has suggested that higher levels of educational attainment are associated with better QoL in later life49,50. Moon51 reported that older women with higher education levels tended to report better QoL compared to those with limited formal education. In this study, descriptive analyses indicated that women had, on average, fewer years of education than men. This lower educational attainment may contribute to reduced health literacy among older women, making them more likely to benefit from healthcare education services that improve their understanding and management of health information. Limited education has been associated with barriers to accessing preventive care, lower engagement in health promotion, and difficulties in navigating complex health systems—challenges that are particularly salient for older women52. For example, Zhang et al.29 found that older adults with lower education levels expressed significantly greater demand for health education programs. International experiences further support this link. In South Korea, long-term care insurance programs have incorporated home-based health counseling and tailored educational interventions to enhance outreach to vulnerable older adults with low health literacy52. These insights underscore the value of integrating targeted healthcare education services within community care models, particularly for older women in China who may face structural and informational disadvantages. Tailored interventions can help bridge health knowledge gaps, promote self-care, and support gender-responsive healthy aging policies.

In addition to the significant association between healthcare education services and better QoL scores among women, other services—such as home visit services, psychological consulting, social and recreational activities, and neighboring relationships—also showed positive but non-significant associations with QoL. These services may support emotional resilience and community engagement, which are particularly valuable for older women, who often have broader social networks but limited financial or caregiving resources53. Their effects, however, may not have been statistically detectable due to regional inconsistencies, variability in delivery quality, or differences in perceived usefulness. By contrast, the perceived availability of personal daily care services, daily shopping assistance, and neighboring relationships was negatively associated with QoL scores. One possible explanation is reverse association, whereby women in poorer health or with greater functional limitations are more likely to be aware of or depend on such services, thus linking their availability with lower self-rated QoL. Moreover, cultural norms in China may lead some women to prefer receiving intimate care from family members rather than external caregivers, especially for tasks involving physical contact54. Prior research has suggested that discomfort with non-familial personal assistance may reduce the perceived acceptability or emotional benefit of such services11. These findings underscore the importance of context-sensitive service design for older women, particularly for services involving bodily care such as personal daily care. They highlight the need to evaluate service effectiveness not only in terms of perceived availability but also by taking into account the unique health conditions, cultural expectations, and caregiving preferences commonly observed among older women in China.

These findings suggest important directions for community care policy, particularly when interpreted in light of international experiences and gender-specific needs. Countries such as the United Kingdom, Japan, and South Korea have developed relatively mature community care systems that offer valuable lessons for China. In the UK, community care is integrated into the national health and social welfare system, with services tailored to individual needs through local coordination mechanisms55. Japan’s long-term care insurance (LTCI) framework provides community-based support with standardized assessment tools and service eligibility criteria, ensuring equitable access across regions20. South Korea has adopted an integrated model linking LTCI with primary care and community-level education, which allows for both health and social needs to be addressed in a coordinated manner56. However, China’s community care system remains in an early stage of institutional development, current pilot programs do not yet systematically incorporate gender as a structural consideration in service planning or delivery. To strengthen and scale up community care in China, several policy directions are recommended.

First, policies should incorporate gender-specific considerations. Given the documented differences in how older men and women engage with and benefit from specific types of services—as shown in this study—it is critical that China’s policy framework evolve to reflect gender-differentiated care needs. For instance, older men may benefit from increased availability of personal care services that support their declining physical independence, while older women may benefit from expanded access to healthcare education services that address lower health literacy and support self-care. Recognizing and responding to gendered patterns of need and service engagement can enhance service relevance and uptake. Learning from international models, China could consider embedding gender-sensitive assessments into service planning tools and developing differentiated service packages by gender. Second, services involving bodily care or instrumental assistance—such as personal daily care or daily shopping support—should be delivered in ways that respect cultural preferences, emotional comfort, and caregiving norms, particularly for women who may feel less comfortable receiving intimate care from unfamiliar sources. Options such as female caregivers, family-inclusive service models, and culturally sensitive training may help address this. Third, a tiered policy framework may offer a balanced approach by setting national-level minimum standards for service types, quality, and access, while allowing local governments to adapt implementation based on regional demographics and infrastructure. This model mirrors the decentralized systems in Japan and South Korea, where central authorities define service principles, but municipalities manage delivery to reflect local needs56. Given China’s pronounced regional disparities, such an approach could enhance flexibility, ensure basic equity, and support more effective and context-sensitive development of community care services. Finally, embedding routine needs assessment, satisfaction tracking, and gender-disaggregated service evaluations into future community care reform efforts could help refine service allocation and delivery strategies. Aligning China’s pilot reforms with evidence-based, gender-responsive practices may enhance the system’s capacity to support healthy aging across diverse population groups.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, because the study employed cross-sectional observational data from the eighth wave of the CLHLS, causal relationships between community care services and older adults’ QoL could not be established. The observed associations reflect correlations rather than causal effects. Second, the independent variables measuring community care services were based on respondents’ self-reported perceived availability rather than actual utilization. This distinction may introduce potential biases, such as over- or underestimation of real exposure to community services, which should be considered when interpreting the findings. Third, although the CLHLS provides rich data, the study relied on a limited set of available variables. Some potentially important factors—such as the size and quality of social networks, objective health assessments, and detailed measures of service utilization—were not included, which may restrict a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms linking community care and QoL.

Future research should explore longitudinal data to better understand causal mechanisms underlying the associations between community care and health outcomes, and to evaluate the long-term impact of service access. Moreover, integrating objective service utilization data alongside perceived availability could improve the accuracy of assessments. Special attention should be paid to evaluating how community care interventions affect different subgroups—particularly across gender, rural–urban settings, and socioeconomic strata—to inform the development of more targeted and inclusive policies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of considering gender differences in the context of community care services for older adults in China. The findings suggest that tailoring community care programs to the differing needs of older men and older women may be relevant, as the associations between specific service types and quality of life vary by gender. Our analysis showed that the perceived availability of personal care services was associated with better QoL scores among older men, while healthcare education services were more strongly associated with better QoL among older women. These gender-specific patterns point to the value of informing community care policy design with sensitivity to gender differences. By acknowledging these variations, policymakers may be better equipped to support the well-being of adults aged 65 and over through more targeted service provision. This study contributes to the growing literature by exploring the associations between perceived community care service availability and QoL, and offers useful considerations for future research and policy development in the context of population aging in China.

Data availability

The research data supporting the results of this manuscript are publicly available through the National Archive of Computerized Data on Aging (NACDA) at the University of Michigan. The CLHLS datasets can be accessed at the following URL: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACDA/studies/36179. Researchers interested in using these data must submit a data use agreement to the CLHLS team as part of the access process.

Change history

31 July 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14141-6

Abbreviations

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- CLHLS:

-

Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

References

United Nations Population Fund. Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and a Challenge. (United Nations Population Fund, 2021).

Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report. World Health Organization. 2021. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017900

Gong, J. et al. Nowcasting and forecasting the care needs of the older population in China: Analysis of data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Lancet Public Health 7(12), e1005–e1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00203-1 (2022).

National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023. Accessed 27 Jul 2023. http://www.stats.gov.cn/en/PressRelease/202302/t20230227_1918979.html

Fang, E. F. et al. A research agenda for aging in China in the 21st century. Ageing Res. Rev. 24(B), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.08.003 (2015).

Huang, H. Q. et al. The smart senior care demand in China in the context of active ageing: a qualitative study with multiple perspectives. Front. Public Health 13, 1505180. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1505180 (2025).

Ishida, M., Kane, S., Ludwick, T., Fan, V. & Mahal, A. Trends in functional limitations among middle-aged and older adults in the Asia-Pacific: Survey evidence from 778,507 observations across six countries. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 54, 101267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101267 (2025).

Reynolds, C. F. 3rd., Jeste, D. V., Sachdev, P. S. & Blazer, D. G. Mental health care for older adults: Recent advances and new directions in clinical practice and research. World Psychiatry 21(3), 336–363. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20996 (2022).

Chu, L. W. & Chi, I. Nursing homes in China. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 9(4), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2008.01.008 (2008).

Feng, Z. et al. Long-term care system for older adults in China: Policy landscape, challenges, and future prospects. Lancet 396(10259), 1362–1372. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32136-X (2020).

Kim, S. et al. Unmet community care needs among older adults in China: An observational study on influencing factors. BMC Geriatr. 24, 719. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05318-1 (2024).

Su, Q., Wang, H. & Fan, L. The impact of home and community care services pilot program on healthy aging: A difference-in-difference with propensity score matching analysis from China. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 110, 104970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2023.104970 (2023).

Chen, Y., Hicks, A. & While, A. E. Loneliness and social support of older people in China: A systematic literature review. Health Soc. Care Community 22(2), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12051 (2014).

Zhou, J. & Walker, A. The need for community care among older people in China. Ageing Soc. 36(6), 1312–1332. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15000343 (2016).

China MoCAotPsRo. Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China 3Q2022. “Civil statistics 2022.” Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.mca.gov.cn/article/sj/tjjb/2022/202203qgsj.html

Yang, L., Wang, L. & Dai, X. Rural-urban and gender differences in the association between community care services and elderly individuals’ mental health: A case from Shaanxi Province, China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06113-z (2021).

Fei, C. & Lin, C. Improving the elderly-care service system: Community care support and health of the elderly. J. Finance Econ. 49, 49–63 (2023).

The Basic Data Bulletin of the Fifth Sample Survey on the Living Conditions of Older Adults in China. China Research Center on Aging. 2024. Accessed April 28, 2025. http://www.crca.cn/images/20241017wdsjgb.pdf

Xia, C. Community-based elderly care services in China: An analysis based on the 2018 wave of the CLHLS Survey. China Popul. Dev. Stud. 3, 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-020-00050-w (2020).

Choi, S. Policy analysis of the community care environment in elderly care: Through comparative analysis of Japan and South Korea. Bull. Inst. Sociol. Soc. Work Meiji Gakuin Univ. 54, 105–138 (2024).

Chen, L. & Ye, M. The development of community eldercare in Shanghai. In Community Eldercare Ecology in China, pp. 55–83 (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4960-1_3

B. Li, Population ageing and community-based old age care supply in China. In Housing and Ageing Policies in Chinese and Global Contexts, C. T. Shum and C. C. L. Kwong, Eds., Quality of Life in Asia, vol. 15, pp. 79–95 (Singapore: Springer, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5382-0_5

Zhang, C. et al. Changes in the demand for socialized elderly care services in Chinese communities and their influencing factors—Based on the longitudinal analysis of CLHLS 2005–2018. World Surv. Res. 5, 3–11 (2022).

Yunong, H. Family relations and life satisfaction of older people: A comparative study between two different hukous in China. Ageing Soc. 32(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X11000067 (2012).

Chen, Y., Hicks, A. & While, A. E. Quality of life of older people in China: A systematic review. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 23(1), 88–100 (2013).

Rodríguez-Romero, R., Herranz-Rodríguez, C., Kostov, B., Gené-Badia, J. & Sisó-Almirall, A. Intervention to reduce perceived loneliness in community-dwelling older people. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 35(2), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12852 (2021).

Hirani, S. P. et al. The effect of telecare on the quality of life and psychological well-being of elderly recipients of social care over a 12-month period: The Whole Systems Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. Age Ageing 43(3), 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft185 (2014).

Yang, L., Wang, L., Di, X. & Dai, X. Utilisation of community care services and self-rated health among elderly population in China: A survey-based analysis with propensity score matching method. BMC Public Health 21, 1936. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11989-x (2021).

Zhang, Z., Mao, Y., Shui, Y., Deng, R. & Hu, Y. Do community home-based elderly care services improve life satisfaction of Chinese older adults? An empirical analysis based on the 2018 CLHLS dataset. Int. J. Environ Res. Public Health 19(23), 15462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315462 (2022).

Van Leeuwen, K. M. et al. What can local authorities do to improve the social care-related quality of life of older adults living at home? Evidence from the adult social care survey. Health Place 29, 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.06.004 (2014).

Chiang, Y. H. & Hsu, H. C. Health outcomes associated with participating in community care centres for older people in Taiwan. Health Soc. Care Commun. 27(2), 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12651 (2019).

Muramatsu, N., Yin, H. & Hedeker, D. Functional declines, social support, and mental health in the elderly: Does living in a state supportive of home and community-based services make a difference?. Soc. Sci. Med. 70(7), 1050–1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.005 (2010).

Chockalingam, A., Singh, A. & Kathirvel, S. Healthy aging and quality of life of the elderly. In Principles and application of evidence-based public health practice, pp. 187–211 (Academic Press, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-95356-6.00007-0

Xu, X., Zhao, Y., Zhou, J. & Xia, S. Quality-of-life evaluation among the oldest-old in China under the ‘active aging framework’. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(8), 4572. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084572 (2022).

Veenhoven, R. Quality of life (QOL), an overview. In Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research, (F. Maggino, Ed.), pp. 5668–5671 (Cham: Springer, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17299-1_2353

Ko, H. et al. Gender differences in health status, quality of life, and community service needs of older adults living alone. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 83, 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.05.009 (2019).

Takayama, A. et al. Association between paid work and health-related quality of life among community-dwelling older adults: The Sukagawa study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 42(5), 1056–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648231152157 (2023).

Woo, S. et al. Gender differences in caregiver attitudes and unmet needs for activities of daily living (ADL) assistance among older adults with disabilities. BMC Geriatr. 23, 671. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04383-2 (2023).

Zhao, E. & Crimmins, E. M. Mortality and morbidity in ageing men: Biology, lifestyle and environment. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 23(6), 1285–1304 (2022).

Freak-Poli, R. et al. Social isolation, social support and loneliness as independent concepts, and their relationship with health-related quality of life among older women. Aging Ment. Health 26(7), 1335–1344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1940097 (2022).

Shi, P. et al. A hypothesis of gender differences in self-reporting symptom of depression: Implications to solve under-diagnosis and under-treatment of depression in males. Front. Psychiatry 12, 589687. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.589687 (2021).

Lu, X. & Dandapani, K. Design of employee pension benefits model and China’s pension gender gap. Glob. Finance J. 56, 100828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2023.100828 (2023).

Freak-Poli, R., Kung, C. S., Ryan, J. & Shields, M. A. Social isolation, social support, and loneliness profiles before and after spousal death and the buffering role of financial resources. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 77(5), 956–971. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbac039 (2022).

Ong, C. H., Pham, B. L., Levasseur, M., Tan, G. R. & Seah, B. Sex and gender differences in social participation among community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 12, 1335692. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1335692 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Individual-level factors attributable to urban-rural disparity in mortality among older adults in China. BMC Public Health 20, 1472. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09574-9 (2020).

Andersen, R. M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter?. J. Health Soc. Behav. 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137284 (1995).

Joo, K. H. Activity level and quality of life of socially engaged elderly—Focusing on gender and age differences. Soc. Welf. Res. 42, 5–39 (2011).

China National Committee on Ageing. Research on the Fourth Sample Survey of the Living Conditions of Urban and Rural Elderly in China. (Hualing Press, 2018).

Han, M. A. et al. Health-related quality of life assessment by the EuroQol-5D in some rural adults. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 41, 173–180. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.2008.41.3.173 (2008).

Lee, D. H. Effects of health status on quality of life in the elderly. J. Korean Gerontol. Soc. 30, 93–108 (2010).

Moon, S. The relationship between socioeconomic status, health status, and health behaviors and health-related quality of life in the elderly: Focusing on gender differences. J. Digit. Convergence 15, 259–271 (2017).

Kim, N. & Ha, I. Rural community care policy challenges. (Korea Rural Economic Research Institute, 2020).

McLaughlin, D., Adams, J., Vagenas, D. & Dobson, A. Factors which enhance or inhibit social support: A mixed-methods analysis of social networks in older women. Ageing Soc. 31(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X10000668 (2011).

Zhang, Y. Cinderella men: Husband-and son-caregivers for elders with dementia in Shanghai. Anthropol. Aging 42(2), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.5195/aa.2021.356 (2021).

Kim, Y. Y. & Yoon, H. Y. Community care overseas cases, implications and concepts. Crit. Soc. Pol. 60, 135–168 (2018).

Mun, H. et al. Patient-centered integrated model of home health care services in South Korea (PICS-K). Int. J. Integr. Care 23(2), 6. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.6576 (2023).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CY, KSY, and WSL equally contributed to study conceptualization, analysis plan, and data interpretation. CY and WSL performed the statistical analyses. CY and KSY wrote the first manuscript draft. CMK and WSL critically revised the manuscript. All the authors have agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted after receiving an exemption from the Korea University Institutional Review Board (KUIRB-2023-0151-01).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the name of the author Suyeon Kim, which was incorrectly given as Suyein Kim.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, Y., Kim, S., Woo, S. et al. Gender differences in the association between community care and quality of life among older adults in China. Sci Rep 15, 24588 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06040-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06040-7