Abstract

As the Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB) continues its rapid economic expansion, the mismatch between the supply and demand of industrial water resources has become increasingly pronounced. While existing research has largely overlooked the decoupling dynamics between industrial water consumption and economic expansion in this region, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of its decoupling relationship, the stability, and the underlying driving forces. Drawing on data from 11 provinces and municipalities in the YREB spanning the 11th to 13th Five-Year Plan (FYP) periods, this study employs the Tapio decoupling model and the logarithmic mean divisia index (LMDI) model as its primary analytical tools. Through comparative analysis, the results reveal that the YREB’s overall decoupling status evolved from weak decoupling in the 11th FYP period to strong decoupling in the 12th and 13th periods, though marked regional disparities persist. Notably, all provinces exhibited some degree of decoupling reversal, primarily during plan transitions, the mid-term of the 12th FYP, or around 2019. This underscores the non-linear and dynamic nature of the decoupling process. In terms of driving factors, during the 11th and 12th FYP periods, the technological effect was the dominant force curbing industrial water consumption, while the output effect was the main contributor to its increase. The interplay between these opposing forces led to fluctuations in the total water consumption effect. However, by the 13th FYP period, structural effect emerged as a significant new restraining force. This study contributes empirical evidence and policy-oriented insights to improve sustainable industrial water management in major river basin economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water resources are one of the irreplaceable natural resources for economic and social development, and guaranteeing water resources plays a crucial role in supporting human survival and progress1. In 1993, to raise public awareness about water conservation, the United Nations designated March 22nd as World Water Day during its 47th International Conference2. In 1998, to scientifically assess the global freshwater situation, the United Nations Water Programme decided to publish the World Water Development Report every three years, later changing it to an annual publication. This information highlights the growing global concern over water resource utilization and protection. As the world’s largest developing country, China’s urban expansion, industrialisation and rapid economic development have paid a hefty price in terms of resources and the environment3. At the same time, water environment problems have become more and more serious, including water shortage, water wastage, pollution of water sources, and increased risks to water security4. To achieve the coordinated development of regional economy and water resources at an early date, the Chinese government has undertaken numerous initiatives to control and manage water environment problems. For instance, to systematically promote the protection and management of water resources, the government introduced the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Water Pollution in 2015. Moreover, to comprehensively promote water conservation in the whole society, the Regulations on Water Conservation and Water Use and other related measures were also enacted in 2024. Scientifically balancing the relationship between economic expansion and water resources consumption has emerged as a key strategy for China’s economic transition.

The YREB, spanning 11 provinces and municipalities in China, serves as a crucial industrial hub and ecological barrier, holding significant strategic importance5,6. By 2021, the regional GDP of the YREB achieved CNY 53.02 trillion, boosting its contribution rate to national economic growth from 47.7 to 50.5%. The YREB has emerged as a new impetus for China’s economic expansion as well as a critical sector for environmental preservation6. With its favorable geographical position, the YREB also hosts a concentration of industries such as equipment manufacturing, raw material processing, and automobile production, and has achieved notable progress in industrial development7. However, this rapid industrialization has led to significant water-related environmental problems, including excessive water consumption and pollution, which pose serious threats to regional water ecological security8. To effectively improve the relationship between industrial development and the water environment and to explore sustainable industrial development pathways, the Chinese government has issued several policy documents, including the “State Council on Relying on the Golden Waterway to Promote the Development of the YREB” and the “Guidelines on Strengthening the Green Development of Industry in the YREB.” Nevertheless, the water resource challenges in the YREB present a dual-edged predicament. On one hand, ensuring a steady and reliable supply of industrial water is essential for bolstering economic advancement. On the other hand, the excessive depletion of water resources has become a significant obstacle to the region’s sustainable progress.

To alleviate this dilemma in a prudent manner, there is a need to dissociate the relationship between resource consumption and the amount of economic expansion, aiming to achieve a “decoupling” of the two. The term “decoupling” originates from physics and was first proposed in the 1960s, referring to the weakening or divergence in the relationship between two physical variables. In 2002, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) extended this concept to environmental economics, defining decoupling as the divergence between economic expansion and resource consumption. The OECD also introduced a decoupling indicator system, which effectively identifies stages of conflict between environmental pressures and economic development9,10. Subsequently, Tapio (2005)11 further refined the OECD’s decoupling indicator system by proposing the decoupling elasticity coefficient and classifying eight specific decoupling states, which is widely recognized by scholars globally. Currently, decoupling theory has been gradually applied to fields such as resource utilization, carbon emissions, and other environmental-economic domains, becoming a research focus12,13. For example, utilizing the Tapio model, Yang et al. (2023) and Duan et al. (2021) explored carbon emission decoupling in Chengdu and water resource decoupling in the Chaohu Lake watershed, respectively13,14.

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have explored the decoupling relationship between water resources and economic expansion. Existing research primarily focuses on two aspects: the status of decoupling and its driving factors. Regarding decoupling status, Zhou and Lai (2025) examined the relationship between agricultural water ecological efficiency and economic expansion in Chongqing from 2015 to 202115. Zhang et al. (2023) conducted a year-by-year analysis of the relationship between green agricultural water resource utilization and agricultural economic expansion from 2008 to 201516. At the regional level, Yang et al. (2025)17Li et al. (2023)18Yang et al. (2022)19, and Jian et al. (2025)20 investigated various aspects of the decoupling between water resource utilization and economic expansion in the Yellow River Basin. Similarly, Wu et al. (2021) assessed the decoupling dynamics between water use and economic development in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region21while Yao et al. (2024) investigated long-term annual trends in the decoupling of tertiary-sector water use and economic expansion across Chinese provinces22. Further research has examined more specific areas, such as the decoupling of the grey water footprint, industrial wastewater, and agricultural grey water footprint23,24,25. In terms of influencing factors, Qian (2022) identified an inverted N-shaped relationship between industrial agglomeration and the decoupling of industrial wastewater26. Qin et al. (2023) argued that the decoupling between socioeconomic development and the lake water environment is largely attributable to the evolution of development paradigms and the reinforcement of water environmental governance12. Li et al. (2023) emphasized that technological advancement plays the most significant role in promoting water resource decoupling in Xinjiang27. Dong et al. (2023) found that changes in water-use intensity and industrial structure have a greater impact on decoupling in the Yellow River Basin28. Moreover, Montoya et al. (2023) highlighted the prominent role of population effects as a driving force of the consumption-related water footprint in Brazil29.

Although existing research has yielded substantial findings on the decoupling relationship between water resources and economic expansion, significant gaps in the critical area of industrial water use decoupling. First, compared to the extensive studies on total water consumption, agricultural water use, and water pollution, systematic research on the decoupling relationship between industrial water use and economic expansion is notably limited. Given that industrial water use is a key component of industrial production, its role in water conservation and efficiency improvement is fundamental to achieving a green and low-carbon transformation. Second, due to the scarcity of research on industrial water use decoupling, the existing literature lacks sufficient exploration of its driving mechanisms, thus failing to fully capture the complex, multifaceted factors at play. Furthermore, at the regional level, studies have frequently focused on areas such as the Yellow River Basin, but research on the decoupling of industrial water use in the YREB—a key national industrial corridor—remains limited. As a result, regional heterogeneity has not been sufficiently explored. Finally, many of the current research centers on annual data series or specific event-based analyses, lacking a perspective that integrates decoupling with the FYP, a critical framework for national macroeconomic regulation. This oversight makes it challenging to fully capture the relationship between policy interventions and the dynamic evolution of industrial water use decoupling.

Against this backdrop, this paper examines the decoupling relationship and its driving factors between industrial water consumption and economic expansion the YREB, through a comparative analysis of different FYP periods. The contributions of this research are threefold: First, it broadens the scope of decoupling studies, as industrial water use plays an important role in supporting economic activities, yet systematic research on industrial water decoupling remains relatively scarce. By focusing on this issue, the paper contributes to advancing the theories of sustainable industrial development and resource management. Second, it reveals the “reversal” phenomenon within the decoupling process. Using the YREB as a case, the study reveals that decoupling is not always linear or unidirectional; instead, it progresses in stages but is subject to setbacks. This finding challenges the tendency to treat decoupling as a straightforward trend, and it enriches the scientific understanding of its nonlinear and dynamic characteristics. Third, it highlights the increasing importance of structural effects in driving industrial water savings. The findings indicate that over time, compared to the offsetting influences of technological progress and output growth, industrial structural adjustments have played an increasingly prominent role in curbing the growth of industrial water use. This underscores the strategic importance of structural transformation in advancing water resource management. Finally, it provides practical insights for global water resource strategic planning and the ongoing “water peak” process. As global water scarcity intensifies, an increasing number of countries are exploring pathways to achieve a “water peak,” seeking to control total water usage and mitigate reversals during economic growth. Using the YREB—a highly industrialized region facing severe water resource pressures—as a case study, this paper provides valuable insights for other countries undergoing rapid industrialization and facing similar water challenges. It highlights the importance of integrating technological advancement, industrial restructuring, and policy cycles, offering practical guidance for developing more adaptive and forward-looking water resource strategies globally.

Research design

Research area

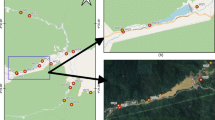

The YREB encompasses 11 provinces and municipalities, spanning the upstream (Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan ), midstream (Jiangxi, Hubei, and Hunan), and downstream (Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui), collectively accommodating over 40% of the nation’s population within approximately 20% of China’s land area30. Spanning East, Central, and West China, the YREB represents a quintessential synergistic development zone, characterized by strong overall competitiveness, significant developmental potential, and remarkable innovative vitality, thereby playing a strategic role in China’s economic landscape31. Moreover, the YREB serves as a pivotal ecological barrier for China, fostering rich biodiversity and hosting several national-level ecological and water conservation zones (refer to Fig. 1).

Figure 1 was produced by the authors using ArcMap 10.7 software (https://www.esri.com), with official administrative boundary data of China (Map Review No. GS (2024) 0650; https://www.tianditu.gov.cn/). The basemap remains unaltered, and the coordinate reference system is Beijing_1954_3_Degree_GK_CM_108E.

Methodologies

Tapio decoupling model

Tapio decoupling elasticity index can express the relationship between two indicators conveniently and directly with specific numerical values, so it has been widely used in the study of decoupling issues in various fields such as energy consumption, carbon emissions, and economic expansion32,33,34. In view of this, this study devises a decoupling indicator that specifically focuses on industrial water consumption and value added in the secondary sector, employing the Tapio model as its foundation35.

In the Eq. (1), the variables are defined as follows: IWU represents industrial water use (in 108cubic meters); INS represents the value added in the secondary sector (in 108 CNY); and TEI represents the Tapio decoupling elasticity index; IWU0 and INS0 represent industrial water use and secondary value added in the base year, respectively, while IWUt and INSt represents the value in the observation year; t represents the period; The symbol \(\Delta\) indicates the difference between the observation year and the base year.

Decoupling is categorized into eight distinct status according to Tapio (2005): Recessive decoupling (RD), Weak decoupling (WD), Strong decoupling (SD), Expansive coupling (EC), Recessive coupling (RC), Expansive negative decoupling (END), Weak negative decoupling (WND), Strong negative decoupling (SND). The ideal state, SD, signifies economic expansion alongside reduced environmental pressures. This indicates a separation between economic expansion and resource consumption, leading to increased resource use efficiency. Conversely, SND represents the least desirable scenario characterized by negative economic expansion and continued growth in resource consumption (refer to Fig. 2).

Drawing on Qi and Chen (2012)36, this study calculates the decoupling stability index for each FYP term to assess the YREB’s decoupling stability.

In Eq. (2), S represents the decoupling stability indicator, n is the number of years, this paper mainly studies the change of 5 years, so n = 5. TEI is the decoupling index in year t. This indicator’s value signifies the stability of the decoupling state and operates inversely: the lower its value, the milder the movement in decoupling state, while a higher value indicates greater variability and instability in the decoupling condition.

LMDI model

The LMDI method boasts several advantages, including the absence of residuals, complete decomposition, ease of operation, and broad applicability, making it a popular choice among factor decomposition techniques. In 1997, Japanese scholar Yoichi Kaya linked carbon emissions with economic, energy, population factor, proposing the Kaya identity37. This identity was employed to assess the influence of each driver on carbon emissions, marking a significant advancement in LMDI model research. Subsequently, scholars have expanded the Kaya-LMDI identity and applied it to water footprint evolution and human well-being level evolution research filed38,39. In 2001, the LMDI-I additive model and LMDI-II multiplicative model were formally introduced40,41,42. The additive decomposition model, known for its intuitiveness, and comprehensive explanation, has gained widespread adoption in resources research43. Drawing from the methodologies outlined by Chen et al. (2019)44 and Xu et al. (2022)45this paper employs the LMDI-I model and Kaya identity to decompose industrial water use.

In Eq. (3), IWU resents industrial water use (in 108 cubic meters), IND denotes industrial value added (in 108 CNY), GDP signifies gross regional product (in 108 CNY), and POP represents resident population (in 104 people).

In Eq. (4), we define T as the technology effect, I as the structural effect, E as the output effect and P as the population effect. We then rewrite Eq. (3) as follows:

As time changes from 0 to t, the industrial water use \(\Delta IWU\) can be segmented into four distinct changes:

The specific formula for each change amount is as follows:

In Eq. (7), \(\Delta T\), \(\Delta I\), \(\Delta E\), and \(\Delta P\) represent the contributions of technology effects, structural effects, output effects, and population effects to the changes in industrial water consumption over the research period, respectively. i denotes provinces and municipalities in the YREB.

Data sources

This study utilizes data from 2005 to 2022 within the YREB as the research sample, and specifically selects resident population (POP), gross regional product (GDP), value added of industrial (IND), value added of secondary industries (INS) and industrial water use (IWU) as the research indicators. All original data used in this study are sourced from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (https://data.stats.gov.cn). Given that the reported industrial water use figures for Jiangxi Province in 2016 and 2017 are identical, this study refers to the Jiangxi Water Resources Bulletin to extend the decimal precision of the data, ensuring distinguishability between the two years and meeting the requirements of the LMDI model. Production value data have been recalculated at constant 2005 prices. Descriptive statistics of the data are shown in Table 1.

Results

Comparison of the industrial water consumption

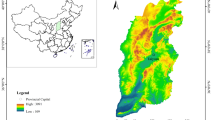

Using total industrial water consumption data from the three FYP periods and the natural breakpoint method in ArcGIS software, we categorized the overall industrial water consumption in the YREB into four classes, ranging from low to high (refer to Fig. 3).

Figure 3 was produced by the authors using ArcMap 10.7 software (https://www.esri.com), with official administrative boundary data of China (Map Review No. GS (2024) 0650; https://www.tianditu.gov.cn/). The basemap remains unaltered and was clipped using provincial boundaries. The coordinate reference system is Beijing_1954_3_Degree_GK_CM_108E.

From a holistic viewpoint, industrial water usage in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River surpasses that in the upper reaches. Jiangsu, Shanghai, Anhui, Hubei, and Hunan consistently rank among the top two categories in terms of usage. From a temporal perspective, a spatial comparison of the three periods shows that the industrial water use levels in Anhui and Jiangxi have increased, while Hubei and Sichuan have decreased, but the category rankings of most other provinces and municipalities remain relatively stable. These findings highlight the significant regional and temporal differences in industrial water use among provinces and municipalities.

Comparison of the decoupling index

Using the decoupling model, we calculated the decoupling status and the decoupling stability index for the 11 provinces and municipalities within the YREB across three consecutive FYP periods (refer to Table 2).

As shown in column (1) of Table 2, the overall industrial water consumption and economic expansion within the YREB exhibited a status of WD, indicating a parallel increase. Only Jiangsu and Zhejiang achieved SD, accounting for 18% of the YREB, while 72% remained in the WD status. This underscores the region’s reliance on water resources for economic expansion during the 11th period. Overall, this suggests that, in general, during the 11th FYP period, the economic development of the YREB depended to a certain extent on water resources, and there is a need for improved coordination between economic expansion and the utilization of natural resources. From a regional perspective, Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, located in the eastern coastal area downstream of the Yangtze River, as one of the most economically developed and technologically advanced regions in China, have already achieved a SD status. Contrastingly, provinces and municipalities in the central and western regions along the middle and upper reaches of the Yangtze River are still in a state of WD. This indicates that these regions still face significant challenges in terms of resource supply and that coordinated development across the eastern, central, and western regions remains essential.

As shown in column (2) of Table 2, the overall decoupling status of the YREB was SD, indicating an inverse trend between industrial water use and economic expansion. Specifically, Shanghai, Hubei, Hunan, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan transitioned to an SD status, resulting in a significant increase in the overall SD rate of the YREB to 73% during the 12th FYP period. However, Anhui and Jiangxi provinces still maintain WD status. Notably, Jiangsu province has transitioned from an SD status to a WD status. Furthermore, in conjunction with the decoupling stability index from columns (4) and (5) of Table 2, Jiangsu province has a stability index of 1.628 during the 11th FYP period, indicating poor stability and the potential for changes in decoupling status. This serves as a reminder to other provinces that have achieved an ideal decoupling status that without continued measures to maintain decoupling stability, the established economic and environment equilibrium could be disrupted.

As shown in column (3) of Table 2, industrial water consumption and economic expansion in the YREB were in a state of SD, that was, economic expansion was accompanied by a decrease in industrial water usage. With the transition of Jiangsu, Anhui, and Jiangxi provinces from a WD state to a SD state during the 13th, the overall decoupling state of the YREB has attained a full SD status. This means that the entire YREB attained the most optimum decoupling state during the 13th FYP period, achieving both economic expansion and resource conservation. This might be connected to the 2015 proclamation of the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Water Pollution, which prioritizes stringent control of the Yangtze River Delta region’s water ecological environment. Jiangsu, Anhui and Jiangxi are all Yangtze River Delta regions, and the change in their decoupling status may be related to this.

In Table 2, as depicted in column (4)-(6), from a comprehensive standpoint, the decoupling stability index of the YREB remained consistently below 1 throughout the three periods of the FYP, signifying a relatively stable decoupling status. Specifically, the decoupling stability index during the 12th FYP period stood at 0.199, representing the most stable phase in terms of overall decoupling status. Conversely, the Thirteenth FYP period exhibited the most unstable decoupling status, with a decoupling stability index reaching 0.806. These findings serve as a reminder to the entire YREB that although an ideal decoupling status has been achieved overall, measures need to be taken to consolidate the achievements and prevent potential reversals in the future.

In addition, we also calculated the year-to-year variation of the decoupling status (refer to Table 3).

From a temporal perspective, the decoupling relationship in the YREB exhibited distinct temporal characteristics. During the 11th FYP period, the decoupling status in various provinces and municipalities was relatively unstable, characterized by a mixed of END EC SD WD statuses. As time progressed, during the 12th FYP period, the decoupling status tended to stabilize, primarily characterized by SD and WD, particularly noticeable in the downstream areas of the Yangtze River and some parts of the midstream area where the trend toward SD was more pronounced. In the 13th FYP period, SD became the predominant decoupling status, with a significant increase observed in the downstream areas, indicating further optimization of the relationship between industrial water consumption and economic expansion. This also validates the gradual transition of development concepts among various provinces and municipalities in the YREB, shifting from prioritizing the development of productive forces with resource conservation as secondary to emphasizing the balanced development of productivity and environmental conservation.

From a regional perspective, notable disparities in decoupling statuses were observed across various geographic zones within the YREB. Across three consecutive three FYP periods, the downstream area primarily exhibited four types of decoupling states: SD, WD, END, and EC. It is noteworthy that by the end of the 13th FYP period, the entire downstream area had achieved a SD status, indicating a favorable balance between industrial development and water resource conservation in the region. In contrast, the midstream area mainly displayed four types of decoupling status: SD, WD, END, and RD. The midstream area exhibited a higher prevalence of WD status over the years, with decoupling statuses distributed unevenly. Even towards the end of the 13th FYP period, the entire area had not achieved the SD status, indicating ongoing challenges in exploring the decoupling path between industrial water consumption and economic expansion. The upstream area primarily exhibited four types of decoupling status: SD, WD, END, and EC. Notably, by the end of the 13th FYP period, all four provinces in the upstream area had achieved the SD status. This to some extent indicates that the upstream economic zone of the Yangtze River, in its commitment to preserving the verdant landscapes and unpolluted waters of the entire YREB, upholds principles of sustainable development, endeavors to mitigate industrial pollution, and safeguards the purity of the Yangtze River from its origins.

From the comparison between provinces and municipalities, significant disparities existed in the decoupling statuses. Zhejiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, and Chongqing consistently demonstrated relatively stable decoupling statuses throughout various FYP periods. They transitioned from END in the early stages of the 11th FYP period to gradually shifting towards WD and SD statuses, signifying a positive trend in decoupling and effective adjustments between water resources and industrial development. In contrast, Shanghai and Jiangsu experienced more considerable variations in decoupling statuses, exhibiting not only SD and WD but also END and EC statuses. This suggests ongoing adjustments in the relationship between industrial water consumption and economic expansion, warranting further exploration towards decoupling pathways. Moreover, Hubei, Hunan, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou primarily exhibited WD and SD statuses. However, during the 12th and 13th FYP periods, several provinces within the YREB exhibited signs of decoupling regression, marked by a resurgence of END and RD statuses. This phenomenon, known as decoupling reversal, reflects a temporary deterioration in previously attained decoupling progress, underscoring the fragile and dynamic nature of sustainable water-resource management.

Comparison of the drivers

In this section, we utilized the LMDI model to dissect industrial water consumption in the YREB, examining it across four dimensions: technological effect, structural effect, output effect, and population effect. The aim was to identify the key drivers influencing the decoupling dynamics between industrial water consumption and economic expansion in the YREB.

Firstly, we compared the average values of each effect during three FYP periods (refer to Fig. 4). The total effect of industrial water consumption in the YREB displayed a declining trajectory. Throughout the 11th FYP period, the dominant force driving industrial water consumption was the output effect, while the technological effect as the primary restraining factor. With the contributory value of driving factors surpassing that of the inhibiting factors, the total effect in the YREB remained positive. Notably, Jiangsu Province exhibited pronounced effects in both output and technology. Furthermore, regions such as Hubei and Anhui, representing high total effects, significantly bolstered the overall elevated levels of industrial water consumption in the YREB. This suggests that the region was amidst a phase of notable economic expansion.

During the 12th FYP period, the total effect on industrial water consumption in the YREB shifted from positive to negative. This transformation was chiefly driven by a substantial surge in the technological effect observed in regions such as Anhui, Hubei, and Hunan. This period underscored an intensified focus on water-saving technologies within the YREB’s industrial landscape. Notably, Jiangsu exhibited a distinct trend in decomposition effects compared to other provinces, marked by a sharp upturn in output effect leading to a shift from negative to positive total effect, indicative of a period of robust industrial expansion.

In the 13th FYP period, the negative trajectory of the total effect of industrial water consumption in the YREB became more pronounced. While technological effect and output effect retained their dominance, their contribution values dwindled. Conversely, the structural effect, acting as a constraining factor, witnessed a significant surge in its contribution value, notably observed in regions typified by Anhui, Jiangxi, Hubei, and Hunan. This suggests that as industrial water-saving technologies mature, their efficacy in water conservation has reached a saturation point, leading to a diminished impact of technological efficiency on reducing industrial water usage. Moreover, with the deepening of the green development concept, the YREB is transitioning from extensive development to intensive protection. During this phase, industrial restructuring is underway, bolstered by various policy measures aimed at ecological preservation and water resource conservation in the YREB. Consequently, the output effect weakened, while the structural effect became increasingly influential.

Analyzing the decomposition effects of each aspect, we observed that output effect and technological effect were the predominant factors influencing industrial water consumption throughout each FYP period, albeit with differing directional impacts. While output effect facilitated the increase in industrial water consumption, it also impeded the decoupling of industrial water consumption and economic expansion. Conversely, technological effect, acting as a factor restraining industrial water consumption, facilitated the decoupling. Structural effect, serving as a constraining factor, has consistently reinforced its role in decoupling. Population effect, as a promoting factor, exerted minimal influence on industrial water consumption in each period and had negligible impact on overall decoupling. Integrating this analysis with the overall decoupling status of the YREB (refer to Table 3), during the 11th FYP period, the failure to achieve SD status was primarily attributed to the high output effect. In the 12th FYP period, the optimization of the overall decoupling status was ascribed to the bolstering of technological effect. By the 13th FYP period, the YREB attained the most desirable SD status, closely correlated with the reinforcement of structural effect.

To delve deeper into the disparities among provinces and municipalities, we conducted a cluster analysis encompassing 11 units. Hierarchical clustering, which groups observations based on their pairwise distances, is widely favored for its simplicity, computational efficiency, and applicability to both continuous and categorical variables. Hence, we adopted this method for our investigation. Following data standardization, we employed Stata 17 software to perform hierarchical clustering using the cumulative contribution values of technological effect, structural effect, output effect, and population effect spanning from 2006 to 2020 as clustering variables, leading to the identification of four sub-regional groups. Moreover, we also calculated the average cumulative contribution values of each effect for the sub-regions within the YREB (refer to Fig. 5).

Before embarking on the comparison, it’s imperative to elucidate that the direction of cumulative contribution values for output effect and population effect, acting as factors propelling the growth of industrial water consumption, is positive, with higher values indicating a more pronounced outward deviation on the graph. Conversely, for technological effect and structural effect, serving as inhibitors to the growth of industrial water consumption, the direction of cumulative contribution values is negative, with higher values indicating a deeper inward deviation on the graph.

Region 1 encompasses five provinces and municipalities: Guizhou, Yunnan, Chongqing, Jiangxi, and Sichuan. The cumulative contribution values of technological effect, structural effect, output effect, and population effect in these areas were all below the average level of the YREB. Consequently, we categorize this region as the “low-low-low-low” type. Despite achieving an ideal SD status by the end of the 13th FYP (refer to Table 3), the pronounced deficiencies in the two dominant factors inhibiting industrial water consumption, namely technological effect and structural effect, underscore the necessity for continued cultivation of water-saving technologies in the manufacturing industry, enhancement of industrial water resource utilization, and optimization of industrial layout to fortify decoupling achievements.

Region 2 comprises three provinces and municipalities: Hubei, Hunan, and Anhui. The cumulative contribution values of technological effect and output effect in these areas surpassed the average level of the YREB, while the cumulative contribution values of structural effect and population effect remained relatively low. Therefore, these areas are classified as “high-low-high-low” type. Given the mutual offset between high technological effect and high output effect in this region, the total effect of industrial water usage is primarily determined by the structural effect. The stronger the structural effect, the more ideal the decoupling status in this region. Hence, this region should continue relocating traditional industries and vigorously developing emerging sectors to optimize its industrial structure.

Region 3 encompasses Shanghai and Zhejiang, where the cumulative contribution values of structural effect and population effect were high, while those of technological effect and output effect were low, defining them as “low-high-low-high” type. This region attained SD status as early as the conclusion of the 12th FYP and has since maintained stability (refer to Table 3), closely tied to its stable economic output, technological support, and structural effect. Both Shanghai and Zhejiang are economically developed regions in China, relying on universities and research institutes to provide a steady stream of funding, technology, and talent support. The concurrent development of economy and technology results in cumulative contribution values of output effect and technological effect, tending to offset each other, thereby establishing a pattern in which the structural effect serves as the primary determinant of industrial water consumption. Even with the influence of population migration, the high structural effect in this region maintains a negative total effect over the years.

Region 4 exclusively includes Jiangsu Province, where the cumulative contribution values of all effects were significantly higher than the average level of the entire YREB, defining it as “high-high-high-high” type. As the only province with high cumulative contribution values in all decomposition effects, the total effect of industrial water consumption was influenced by each factor. Consequently, the decoupling status was also affected by a mixture of factors, leading to significant fluctuations, consistent with the results in Table 3. When the cumulative contribution values of technological effect and structural effect, which inhibit the growth of industrial water consumption, are substantial, this region is in an ideal decoupling state. Conversely, when the cumulative contribution values of output effect and structural effect, which promote industrial water consumption, are substantial, the decoupling efforts in this region will regress. This cyclical fluctuation is likely to persist.

Discussion

From a longitudinal perspective on the decoupling relationship between industrial water consumption and economic expansion across the YREB, the decoupling process has not advanced in a linear manner, but has instead experienced periodic fluctuations and adjustments. Xu and Liu (2023)46 and Zhang et al. (2020)47 found that the overall decoupling states of water resources in the YREB have changed from weak to strong with a positive trajectory. Compared with them, this article analyzes the decoupling status in different periods and regions in more detail. Our analysis reveals that most provinces within the region have encountered instances of “decoupling reversal” in decoupling states of industrial water consumption, where previously achieved decoupling statuses underwent temporary reversals, often regressing from the ideal SD state to less desirable states such as WD or END48. Further examination of the timing and spatial distribution of these reversal episodes identifies three main periods of concern:

First, decoupling reversal tends to occur during transitions between FYPs, specifically in 2010–2011 (transition from the 11th to 12th FYP), 2015–2016 (12th to 13th), and 2020–2021 (13th to 14th). During these intervals, nearly all provinces in the YREB experienced varying degrees of decoupling reversal. This can be attributed to policy reorientation and administrative restructuring typical of plan transitions, often accompanied by increased macroeconomic volatility, adjustments in statistical methods, and shifts in governance priorities. As a result, water-saving policies may lose continuity and enforcement intensity, introducing regulatory uncertainty and weakening previous decoupling gains.

Second, around 2019, provinces such as Jiangxi, Hubei, and Guizhou exhibited reversal trends primarily due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic disrupted industrial supply chains and demand structures, reducing water-use efficiency per unit of economic output. These effects were compounded by localized production shutdowns and the resumption of certain infrastructure projects, intensifying volatility and pressure in industrial water management.

Third, a notable reversal occurred during the mid-stage of the 12th FYP (2012–2013), affecting Shanghai, Jiangsu, Anhui, Jiangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan. Analysis of underlying drivers indicates that although technological effects continued to strengthen and played a significant role in curbing industrial water use, the economic output effect increased substantially in many regions. This led to a situation where economic expansion offset the benefits of technological progress, a phenomenon that could be described as “economic output masking water-saving gains”. For example, while Shanghai achieved a notable reduction in total industrial water consumption—driven by technological advancement—the concurrent growth in output exerted upward pressure. Similarly, Jiangsu experienced a sharp rise in output effect, which consequently led to an overall increase in industrial water use. In Anhui and Jiangxi, the contribution of output effect was also significant within the YREB. Moreover, despite improvements in technological effects in Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan, these advancements were insufficiently responsive to mitigate the increasing pressure driven by economic output growth.

From the perspective of the evolution of industrial water consumption driving factors, technological effects were the primary force behind the decline in total effects during both the 11th and 12th FYP periods. In contrast, economic effects acted as the main driver of total effects, which aligns with the findings of previous studies25,49. However, during the 13th FYP period, the contribution of structural effects increased significantly, acting as a new impetus for industrial water conservation. As illustrated in Fig. 4, technological and economic effects counteracted each other, a pattern especially evident in the 11th and 12th Plan periods. Across the YREB and its constituent provinces, the interplay between dominant technological and output effects has resulted in considerable fluctuations in total industrial water consumption effects. In the 13th Plan period, this mutual offsetting became more prominent, while structural effects showed a marked strengthening trend. Consequently, most provinces—except for a few such as Shanghai and Guizhou—experienced a notable decline in total industrial water use effects, leading to a clear downward trend for the entire region. These results suggest that industrial restructuring is emerging as an equally important driver alongside technological advancement in sustaining the decoupling process—an important insight that distinguishes this study from previous research focused primarily on the technological pathway25,27.

Overall, the observed “decoupling reversal” highlights specific stages of vulnerability in the decoupling process, while the driving factor analysis reveals the core pathways and their temporal shifts for industrial water savings in different regions. Based on these findings, this study makes the following recommendations. First, the YREB as a whole should strengthen cross-regional coordination and structural regulation mechanisms to enhance the stability and long-term sustainability of the decoupling process. A dynamic monitoring and emergency response mechanism should also be established, with particular attention to critical periods such as FYP transitions and phases of significant economic volatility, in order to identify and respond to potential reversal risks in a timely manner. Second, according to the results of the clustering analysis, the middle reaches (Hubei, Hunan, Anhui) and upper reaches (Chongqing, Guizhou, Yunnan, Sichuan) of the Belt exhibit structural effects that fall below the regional average. This indicates a relatively weak contribution of industrial structure to water conservation in these areas. Therefore, it is recommended that these regions implement differentiated industrial adjustment policies, including stricter access thresholds for water-intensive industries, promotion of green transitions in traditional sectors such as he heavy chemical industry, construction materials, and textiles, and accelerated development of low-water-use, high value-added industries such as water-efficient manufacturing, new materials, and biopharmaceuticals to enhance overall industrial water-use efficiency.

Naturally, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the analysis focuses on the YREB and does not extend to other key economic zones such as the Pearl River Delta or the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, which may exhibit different decoupling characteristics due to varying industrial structures and water policies. Second, the industrial sector is treated as a homogeneous entity, without disaggregation into specific sub-sectors. This limits the ability to identify sector-specific drivers of water-use decoupling. Third, due to data availability constraints, the analysis ends in 2022, which precludes assessment of the initial impact of China’s 2024 Water Conservation Regulations.

Conclusion and prospects

Using the method of comparative analysis, this paper studies the decoupling status of industrial water consumption and economic expansion in the YREB during the 11th, 12th and 13th FYP periods, and analyses the pivotal factors influencing their decoupling relationship. The findings are as follows:

Throughout the three consecutive FYP periods, the decoupling status in the YREB exhibits a clear chronological pattern. During the 11th FYP period, the YREB displayed a mix of END, EC, SD, and WD statuses. Progressing into the 12th FYP period, decoupling tended towards stabilization, with SD and WD prevailing. By the 13th FYP period, SD emerged as the predominant status, although the overall stability of decoupling during this period was weaker compared to the previous two phases. Nonetheless, significant spatial heterogeneity persisted. Provinces like Zhejiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, and Chongqing consistently demonstrated stable and positive decoupling throughout each FYP period. Conversely, Shanghai and Jiangsu exhibited more fluctuating decoupling statuses, encompassing END, EC, SD, and WD. Notably, this study finds that various provinces and municipalities within the YREB experienced some degrees of decoupling reversal, during the transitions between FYPs, the mid-term of the 12th FYP, or around 2019. These findings highlight the non-linear and dynamic nature of the decoupling process, emphasizing the importance of continuously reinforcing water-saving measures to prevent reversals.

Throughout the three consecutive FYP periods, the total impact of industrial water consumption in the YREB has exhibited a declining trajectory, with the technology effect consistently serving as the primary factor restraining the escalation of industrial water usage, while the output effect acts as the enabling factor. During the 11th FYP period, the contribution of the output-promoting effect exceeded that of the inhibitory technological effect, resulting in a positive total effect in the YREB, indicating a period of substantial economic expansion. In the 12th FYP period, the total effect in the YREB shifted from positive to negative, with the technology effect, as the primary inhibiting factor, experiencing a notable increase, reflecting the region’s heightened focus on industrial water-saving technologies during this period. In the 13th FYP period, the negative trend of the total effect in the YREB became more pronounced, accompanied by a decrease in contribution values for both the technology effect and the output effect. Meanwhile, the contribution value of the structural effect, as an inhibitory factor, witnessed a sharp rise, suggesting significant industrial structural adjustments within the YREB during this period, yielding notable effects. Cluster analysis further reveals pronounced spatial heterogeneity. The upstream areas (Chongqing, Guizhou, Yunnan, Sichuan) consistently underperformed across all decomposed effects relative to the YREB average. In the midstream region (Hubei, Hunan, Anhui), the cumulative contributions of both structural and demographic effects remained comparatively low. In contrast, Shanghai and Zhejiang recorded relatively modest cumulative values for technological and output effects. Jiangsu stands out due to its significantly higher cumulative contributions across all decomposed effects relative to the YREB average, underscoring its dominant position in regional industrial water-use dynamics.

Building upon the current work, future research could be expanded in several ways. First, comparative studies across multiple economic regions within China—or even across countries—could offer broader insights into how regional variations shape decoupling trajectories. Second, future studies could disaggregate the industrial sector to examine water-use decoupling patterns in high-consumption industries such as metallurgy, chemical production, and textiles, allowing for more targeted policy recommendations. Finally, with the recent enactment of China’s Water Conservation Regulations, future research could employ a policy evaluation framework to assess their effectiveness on industrial water-use decoupling.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author, [Xiujuan Gong: gxj990303@163.com], upon reasonable request.

References

Chen, H., Yang, X., Bian, D. & Xiang, W. A novel composite cloud model-based three-stage evaluation for the spatial equilibrium of water resources in China. J. Clean. Prod. 456, 142356 (2024).

Shi, X. The safety of drinking water in China: Current status and future prospects. China CDC Wkly 2, 210–215 (2020).

Tan, J., Su, X. & Wang, R. The impact of natural resource dependence and green finance on green economic growth in the context of COP26. Resour. Policy 81, 103351 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Enhanced evapotranspiration induced by vegetation restoration may pose water resource risks under climate change in the Yellow River Basin. Ecol. Ind. 162, 112060 (2024).

Liu, L. et al. A comparative study of green growth efficiency in Yangtze River Economic Belt and Yellow River Basin between 2010 and 2020. Ecol. Ind. 150, 110214 (2023).

Zhao, J. & Zhao, Y. Synergy/trade-offs and differential optimization of production, living, and ecological functions in the Yangtze River economic Belt, China. Ecol. Indicat. 147, 109925 (2023).

Wang, Y., Duan, X., Wang, L. & Zou, H. Spatial temporal patterns and driving factors of industrial pollution and structures in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Chemosphere 303, 134996 (2022).

Lei, Y., Huang, L. & Zhang, H. Research on the dynamic evolution and the driving factors of industrial water consumption efficiency in China. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 26, 159–170 (2017).

Development (OECD), Indicators to measure decoupling of environmental pressure from economic growth. (OECD Paris, 2002).

Dong, F. et al. Causal chain of haze decoupling efforts and its action mechanism: Evidence from 30 provinces in China. J. Clean. Prod. 245, 118889 (2020).

Tapio, P. Towards a theory of decoupling: Degrees of decoupling in the EU and the case of road traffic in Finland between 1970 and 2001. Transp. Policy 12, 137–151 (2005).

Qin, X., Hu, X. & Xia, W. Investigating the dynamic decoupling relationship between regional social economy and lake water environment: The application of DPSIR-Extended Tapio decoupling model. J. Environ. Manage 345, 118926 (2023).

Yang, F., Shi, L. & Gao, L. Probing CO2 emission in Chengdu based on STRIPAT model and Tapio decoupling. Sustain. Cities Soc. 89, 104309 (2023).

Duan, T., Feng, J., Zhou, Y., Chang, X. & Li, Y. Systematic evaluation of management measure effects on the water environment based on the DPSIR-Tapio decoupling model: A case study in the Chaohu Lake watershed, China. Sci. Total Environ. 801, 149528 (2021).

Zhou, X. & Lai, P. Measurement, decoupling relationship and driving factorsanalysis of agricultural water eco-efficiency in Chongqing municipality based on three-dimensional ecological footprint model. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. https://doi.org/10.19741/j.issn.1673-4831.2024.0570 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Guo, T. & Zhang, Z. Research on the decoupling relationship between agricultural green water resources utilization and agricultural economic growth. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Region. Plann. 44, 103–113 (2023).

Yang, Y., Wang, Y. & Xu, Q. Driving factors and decoupling effect of water resources utilization in the Yellow River Basin. Arid Land Geography 48, 20–30 (2025).

Li, R. et al. Decoupling and decomposition of driving factors of water resources utilization and economic growth in the Yellow River Basin. Geographical Sci. 43, 110–118 (2023).

Yang, Y., Wang, Y. & Xu, Q. Decoupling analysis of water utilization and economic development in the Yellow River Basin: Based on quantity and quality of water resources. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 33, 1–10 (2022).

Jian, S., Cheng, X., Wang, T. & Dou, S. The driving factors of water use and its decoupling relationship with economic development—A multi-sectoral perspective in the nine provinces of the Yellow River Basin. J. Hydrol. Region. Stud. 59, 102338 (2025).

Wu, D., Li, A. & Zhang, C. Evaluation on the decoupling between the economic development and water resources utilization in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region under dual control action. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 31, 150–160 (2021).

Yao, Y., Li, H., Li, W., Zhao, Y. & Wang, L. Development of water use of the tertiary industry based on Tapio decoupling and LMDI. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 35, 71–81 (2024).

He, W., Kong, Y. & Shen, J. A two-dimensional decoupling analysis of grey water footprint and economic growth in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. J. Hohai Univ. (Philosophy and Social Sciences) 24(68–74), 111 (2022).

Xu, R. & Liu, W. Relationship between agricultural grey water footprint and economic growth in the yellow river basin: Based on decoupling and rebound effects. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Region. Plann. 44, 79–91 (2023).

Zhang, H., Chen, Z. & Zhang, C. Decoupling efforts of environmental pressure of lndustrial wastewater and economic growth in Yangtze River Economic Belt. Areal Res. Dev. 38, 13–18 (2019).

Qian, M. How can industrial wastewater be decoupled from Industria agglomeration? Evidence from 276 prefectural-level cities in China. Front. Sci. Technol. Eng. Manag. 41, 69–75 (2022).

Li, D., Zuo, Q., Jiang, L. & Wu, Q. An integrated analysis framework for water resources sustainability considering fairness and decoupling based on the water resources ecological footprint model: A case study of Xinjiang, China. J. Clean. Product. 383, 135466 (2023).

Dong, R., Zhou, X., Zhang, Y. & Wang, N. Water consumption decoupling and influencing factors in the yellow river basin based on the triple attributes of water resources. Yellow River 45, 83–87 (2023).

Montoya, M. A., Allegretti, G., Bertussi, L. A. S. & Talamini, E. Domestic and foreign decoupling of economic growth and water consumption and its driving factors in the Brazilian economy. Ecol. Econ. 206, 107737 (2023).

Zhao, Z., Zhang, L. & Deng, C. Changes in net anthropogenic nitrogen and phosphorus inputs in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China (1999–2018). Ecol. Ind. 145, 109674 (2022).

Yang, T., Zhou, K. & Ding, T. Air pollution impacts on public health: Evidence from 110 cities in Yangtze River Economic Belt of China. Sci. Total Environ. 851, 158125 (2022).

Hu, M., Li, R., You, W., Liu, Y. & Lee, C.-C. Spatiotemporal evolution of decoupling and driving forces of CO2 emissions on economic growth along the Belt and Road. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 123272 (2020).

Li, R., Li, L. & Wang, Q. The impact of energy efficiency on carbon emissions: Evidence from the transportation sector in Chinese 30 provinces. Sustain. Cities Soc. 82, 103880 (2022).

Rajabi Kouyakhi, N. CO2 emissions in the Middle East: Decoupling and decomposition analysis of carbon emissions, and projection of its future trajectory. Sci. Total Environ. 845, 157182 (2022).

Zhang, H., Xu, T. & Zhang, C. Decoupling of industrial water use and economic development in the Yangtze River Delta region. Resour. Ind. 24, 115–125 (2022).

Qi, J. & Chen, B. Decoupling analysis for urban industrial sectors: A case study of Chongqing. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 22, 102–106 (2012).

Kaya, Y. & Yokobori, K. et al. Environment, energy, and economy: Strategies for sustainability. (United Nations University Press Tokyo, 1997).

Fu, T., Xu, C., Yang, L., Hou, S. & Xia, Q. Measurement and driving factors of grey water footprint efficiency in Yangtze River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 802, 149587 (2022).

Zhong, C., Ma, X. & Zheng, G. Regional differences and driving effects of China’s provincial common prosperity level. Econ. Geography 43, 12–20 (2023).

Ang, B. W. LMDI decomposition approach: A guide for implementation. Energy Policy 86, 233–238 (2015).

Ang, B. W. & Liu, F. L. A new energy decomposition method: Perfect in decomposition and consistent in aggregation. Energy 26, 537–548 (2001).

Jiang, P. et al. Research on spatial and temporal differences of carbon emissions and influencing factors in eight economic regions of China based on LMDI model. Sci. Rep. 13, 7965 (2023).

Zhao, X., Zhang, X. & Shao, S. Decoupling CO2 emissions and industrial growth in China over 1993–2013: The role of investment. Energy Econ. 60, 275–292 (2016).

Chen, K., Guo, Y., Liu, X., Jin, G. & Zhang, Z. Spatial-temporal pattern evolution of wastewater discharge in Yangtze River Economic Zone from 2002 to 2015. Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C 110, 125–132 (2019).

Xu, C., Liu, Y. & Fu, T. Spatial-temporal evolution and driving factors of grey water footprint efficiency in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Sci. Total Environ. 844, 156930 (2022).

Xu, B., Yang, X., Yuan, N. & Li, Y. Decoupling relationship between agricultural water consumption and agricultural economic development of Changjiang River economic belt. Yangtze River 1–9 (2023).

Zhang, H., Chen, C. & Zhang, C. Driving effect of decoupling between economic growth and water consumption in Yangtze River Economic Belt comparative analysis based on “Eleventh Five-Year Plan” and “Twelfth Five-Year Plan” periods. J. Econ. Water Resour. 38(30–35), 82 (2020).

Zhang, H., Huang, Y., Wang, R., Zhang, J. & Peng, J. Decoupling and spatiotemporal change of carbon emissions at the county level in China. Resour. Sci. 44, 744–755 (2022).

Ma, H., Jiang, M. & Hou, Y. Study on decoupling effect of urbanization of the Yangtze River Economic Belt to industrial water use: Based on the comparative analysis of the data of the period of “11th Five Year Plan” and “12th Five Year Plan”. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 27, 1683–1692 (2018).

Funding

This work was supported by the Strategic Research and Consulting Project of the Chinese Academy of Engineering (Project Numbers: 2024-XZ-71 & 2024-HZ-05), and supported by Postgraduate Innovation Fund Project by Southwest University of Science and Technology (Project Numbers: 24ycx2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Methodology & Software & Formal analysis & Data curation & Writing, X. G.; Writing & Review & Editing, S. L.; Visualization & Review, L. L.; Review & Editing W. Y. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, X., Liu, S., Ye, W. et al. Decoupling of industrial water consumption and economic expansion in the Yangtze River Economic Belt: a comparative analysis across three Five-Year plans. Sci Rep 15, 21186 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06042-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06042-5