Abstract

This study aimed to determine whether β-lactamase-like protein (Lactamase-β, LACTB) influences apoptosis in gastric cancer cells by modulating mitochondrial autophagy through the PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) or Parkin pathway. Firstly, the expression level of LACTB in gastric cancer tissues was detected by immunohistochemistry, and the survival data of patients were used to explore the relationship between LACTB expression level and patient prognosis. Secondly, LACTB overexpression (+ LACTB) and knockdown (sh-LACTB) AGS gastric cancer cell lines were constructed; flow cytometry and other experiments were used to detect the effect of LACTB on AGS cell apoptosis; Western Blot was used to detect the expression of PINK1/Parkin mitochondrial autophagy pathway-related proteins and lysosome-related proteins in + LACTB and sh-LACTB gastric cancer cells; kits and electron microscopy were used to detect changes in the number of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and autophagosomes. Finally, Western blot was used to detect the expression of apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 associated x protein (Bax) and B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) in + LACTB and sh-LACTB gastric cancer cells treated with mitochondrial autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA). Immunohistochemistry analysis revealed that LACTB expression in gastric cancer tissues was higher than in adjacent non-cancerous tissues, for patients with tumor diameters exceeding 4.5 cm, high LACTB expression was associated with a poor prognosis (P < 0.05). LACTB overexpression reduced apoptosis in gastric cancer cells. It downregulated the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, while LACTB knockdown promoted apoptosis, upregulated Bax, the expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bax, and downregulated the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. In LACTB overexpressing cell lines, protein sequestosome 1 (P62) protein levels were elevated, lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2) expression was decreased, Reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels remained significantly stable, and autophagosome counts were reduced. Conversely, LACTB knockdown cells, PINK1, Parkin, protein light chain 3II/I (LC3II/I), LAMP2, cathepsin B (CTSB), continuous traumatic stress disorder (CTSD), and other related proteins, downregulated P62 expression, increased ROS accumulation, and higher number of autophagosomes. In LV-LACTB and sh-LACTB gastric cancer cells treated with the mitochondrial autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA), apoptotic protein Bax is downregulated, and anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 is upregulated. In summary, the LACTB protein may regulate the apoptosis in gastric cancer cells by modulating mitochondrial autophagy through the PINK1/Parkin pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer is a common malignancy of the digestive tract and a significant health threat to human health. Recent global statistics found that gastric cancer ranks fifth in incidence and fourth in mortality among human malignancies1,2. In China, gastric cancer incidence is particularly high. Due to its often asymptomatic onset and lack of specific early symptoms, most cases are diagnosed at intermediate or advanced stages3,4,5. Lousy living habits and Helicobacter pylori infection are all high-risk factors for gastric cancer, and its incidence is becoming younger6,7. For early-stage gastric cancer, surgery is the primary treatment option8; for intermediate and advanced stages, treatment typically combines surgery with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, though overall outcomes remain suboptimal9,10. Therefore, an in-depth exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying gastric cancer development and progression is significant for improving diagnosis and treatment.

β-lactamase-like protein (LACTB) is a mammalian mitochondrial membrane-associated protein derived from bacterial penicillin-binding protein and β-lactamases. It regulates mitochondrial lipid metabolism by synthesizing peptidoglycan, subsequently influencing cell differentiation11,12. Early studies found downregulated of LACTB in tumor tissues such as hepatocellular carcinoma13, breast cancer14, colorectal cancer15, glioma16, lung cancer17, and melanoma18 while it is overexpressed in nasopharyngeal carcinoma19 and pancreatic cancer20, where it is linked to a patient with poor prognosis. Our previous research found that LACTB is highly expressed in gastric cancer cells, and overexpression of LACTB can promote cell invasion and migration21. However, the detailed mechanism by which LACTB influences gastric cancer progression remains unclear.

Mitochondrial autophagy is essential for removing damaged or surplus mitochondria, helping to maintain cellular homeostasis22. Classical mitochondrial autophagy pathways include the PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin ubiquitination pathway and the mitochondrial receptors BINP3/NIX and FUNDC1 pathways, activated by mitochondrial depolarization, hypoxia, or metabolic stress23. Among these, the PINK1/Parkin pathway is the most extensively studied mitochondrial autophagy pathway. Autophagy and apoptosis are critical, interconnected processes regulating cell survival, with their interplay varying across biological contexts. The binding of autophagy-related molecules to apoptotic molecules has been indicated to promote apoptosis24. Previous studies have demonstrated that LACTB induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells by activating endogenous caspase-independent pathways25. Consequently, we hypothesized that LACTB might regulate apoptosis in gastric cancer cells by activating the PINK1/Parkin mitochondrial autophagy pathway, thereby impacting tumor progression.

Materials and methods

Specimen collection

We collected 183 gastric cancer tissue specimens from the gastrointestinal surgery department at the affiliated hospital of Guizhou Medical University from January 2014 to December 2018. All patients underwent radical gastric cancer surgery, and diagnoses were confirmed through pathological examination. Patient’s relevant clinical information and follow-up information were collected simultaneously, and the follow-up time interval ranged from 0 to 95 months. All tissue specimens collected for this study complied with the ethical standards established by the ethics committee(Approval Letter No.: 2021 Ethics No. 030, Human Trials Ethics Committee of Guizhou Medical University).

Bioinformatics analysis

Using the oncomine database( http://www.oncomine.org )to analyze the expression of LACTB messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) in gastric cancer. Log in to the oncomine database, enter “LACTB” in the search bar, then enter gastric and select the statistical chart of the ChoGastric Statistics study.

Design of specific primers for LACTB gene

Through the NCBI database, it was determined that LACTB (GeneID: 114294) consists of 7 exons and 3 standard mRNAs annotated as NM sequences: transcript 1 (V1, NM_032857.5), transcript 2 (V2, NM_171846 0.4), and transcript 3 (V3, NM_001288585.2), as well as 2 non-coding mRNAs annotated as XR sequences: XR1 (XR_931745.2) and XR2 (XR_429442.2). Specific primers were designed based on gene characteristics to detect the expression level of LACTB mRNA, as shown in Table 1.

Cell culture

Human gastric cancer cell lines AGS, human gastric carcinoma cell line (HGC-27), human gastric cancer cell line-28 (MKN-28), and MKN-45 were all purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences cell bank. All cells were cultured in a complete medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) at 5% CO2 and 37 ℃. Subculture is performed every 2–3 days. Cells in the logarithmic growth phase were collected for experiments.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed and dehydrated for antigen retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide, followed by blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA). After removing the excess blocking solution, the primary antibody (LACTB, Abcam) was used, and sections were slowly incubated at 4 ℃ in a humidified chamber. The sections were washed thrice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) for 5 min each time. After brief drying, the slices were slightly shaken to dry, and the secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-labeled) of the species corresponding to the primary antibody was added to the circle to cover the tissue and incubated at room temperature for 50 min each. Wash again with PBS (pH 7.4) 3 times for 5 min each time. Finally, the slices are slightly shaken and dried, freshly prepared Diaminobenzidine (DAB) color-developing solution is dripped into the circle, and the color-developing time is controlled under the microscope. Positive staining appeared brownish yellow, and sections were washed with tap water to halt development. Hematoxylin was used for nuclear staining for 3 min, followed by bluing in running water. Sections were then dehydrated, sealed, and observed under a light microscope for result interpretation.

Analysis of immunohistochemical results

Following a previous method27, more than five high-power fields of view were randomly selected for each section, with 200 cells counted per field, totaling 1000 cells per section, and the average was three times. Two experienced pathologists independently determined the sections. The criterion for determining staining results was the staining intensity score multiplied by the positive cell rate score. (1) Dyeing intensity: tan (3 points), brown yellow (2 points), light yellow (1 point), negative (0 point). (2) Positive cell rate: ≤ 10% (score 0), 11–25% (score 1), 26–50% (score 2), 51–75% (score 3), > 75% (score 4). (3) Final classification criterion: the product of staining intensity and the positive rate of stained areas. LACTB takes the median value of five in all cases as the cut-off value, and scores ≥ 5 are considered high expression, and < 5 are considered low expression.

Real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR reaction

RNA was extracted from gastric cancer cell lines using the UNIQ-10 column Trizol total RNA extraction kit (Sangon Biotech, B511321-0100) by the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, RR047A). TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Takara, RR820A) was employed for RT-qPCR analysis, with HPRT serving as an internal reference gene for determining the relative expression level of LACTB. The data were analyzed via the 2-ΔΔCt method to evaluate the relative expression of the target gene.

Western blotting

Typically, 80 µL of phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)-containing lysis buffer was added to each well of the 6-well plate, then place the 6-well plate on ice for 30 min, and finally extract the total protein. Protein concentrations were then measured using the bicinchoninic acid kit (Solarbio). The total protein mass loaded in each well was 30 µg and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Specific primary antibodies were used to detect target proteins. Images were acquired using a Borough blot exposure instrument, and the integrated optical density of the protein bands was detected by Image J analysis software. Samples were simultaneously detected for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase protein bands as internal control. Related primary antibodies included Bax, Bcl-2, PINK1,Parkin, LC3A/B, LAMP1, LAMP2, CTSB, CTSD (CST), SQSTM1/p62, LACTB (Abcam).

Construction of LACTB over-expressed stable strain by over-expressing lentivirus vector

The LACTB gene transcript variant 1 (NM_032857.5) was ligated to the vector Ubi-MCS-SV40-EGFP-IRES-puromycin (numbered GV367, Gene Kai). AGS cells were infected with lentivirus and overexpressed LACTB to generate the AGS empty cell line (Vector1) and the AGS overexpressing stable line (+ LACTB). Finally, puromycin at a concentration of 2 µg/mL was used to remove uninfected cells and to acquire 100% infection efficiency cells.

Construction of LACTB knockdown stable strain by RNA interference (RNAi) lentiviral vector

The small interfering RNA sequence (LACTB – RNAi – 67213-1: GAGCAGGAGAATGAAGCC AAA) of LACTB transcript variant 1 (NM_032857.5) was inserted into the vector of hU6 – MCS – CBh – gcGFP – IRES - puromycin (No. gv493, Gene Kai), and the AGS cell line was infected to generate the LACTB knockdown AGS cell strain (sh-LACTB). The AGS empty vector stable strain (Vector 2) was simultaneously constructed. Finally, puromycin at a concentration of 2 µg/mL was used to remove uninfected cells and to acquire 100% infection efficiency cells.

Apoptosis detected by flow cytometry

Cells in the logarithmic growth phase had their medium removed, washed twice with cold PBS, and resuspended in 1 binding buffer at a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/mL. A 100 µL cell suspension (1 × 105 cells) was transferred to a 5-mL culture tube. Subsequently, 5 µL of fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC) Annexin V and 5 µL of Propidium Iodide (PI) were added, and the cells were gently vortexed and incubated in the dark at room temperature (25 ℃) for 15 min. Finally, 400 µL of 1 binding buffer was added to each tube, and flow cytometry was performed within 1 h.

Reactive oxygen species detection

Cells were harvested when the cell density reached 50%~60% in a 6-well plate culture. After removing the medium, the cells were washed twice with a serum-free medium. Subsequently, 500 µL of dihydroethidium (DHE) probe diluted in serum-free culture medium to a working concentration of 10 µM was added. The concentration and volume of the DHE probe were adjusted according to the actual experimental situation. Cells were incubated at 37 ℃ for 10–90 min, with gentle mixing every 5 min to ensure complete contact with the probe and the sample. After removing the supernatant, cells were washed twice with a serum-free medium, and fluorescence was detected using a fluorescence microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy

Cells in the logarithmic growth phase were collected, and the medium was removed. Electron microscope fixative solution was added, and cells were fixed at 4 ℃ for 2–4 h, wrapped with 1% agarose, and rinsed with 0.1 mol/L PBS buffer (pH 7.4) three times for 15 min each time. The samples were then fixed in 1% osmium acid of 0.1 mol/L PBS buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature (20 ℃). Acetone: 812 embedding agents = 1:1 and soaked for 2–4 h, followed by acetone: 812 embedding agents = 2:1 permeated overnight. Pure 812 embedding agents were used for 5–8 h; the pure 812 embedding agent was placed into the embedding plate, the sample was placed into the embedding plate, and then kept in the oven at 37 ℃ overnight and polymerized at 60 ℃ for 48 h. The ultra-thin section (60–80 nm) was prepared, and sections were double stained with uranium and lead (2% uranium acetate saturated alcohol solution, lead citrate, each staining for 15 min). Sections were air-dried overnight at room temperature and examined under a transmission electron microscope and images were taken to observe the number of autophagosomes in the cells.

Statistical methods

Data analysis was conducted using a Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (version 25.0) and GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0.1). For data conforming to a normal distribution, an independent samples t-test was used; otherwise, results are presented as the median (interquartile range) [M (P25-P75)]. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for inter-group comparisons, and the Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for multi-group comparisons. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of LACTB in gastric carcinoma tissue and its effect on patient survival

Bioinformatics analysis indicated that the mRNA expression level of LACTB in gastric carcinoma tissue was significantly higher than that in normal controls (P < 0.05, Fig. 1A). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that LACTB protein was mainly localized in the cytoplasm. Using paracancerous tissues as the control group, the expression level of LACTB in gastric cancer tissues was higher than that in paracancerous tissues (P < 0.001, Figs. 1B-C). By analyzing the relationship between LACTB expression level and basic clinical data of patients, it was found that age, gender, TNM stage, and other factors did not affect the expression of LACTB protein(Table 2). However, the survival analysis of 61 patients with tumor diameters greater than 4.5 cm revealed that the survival time of patients in the high-LACTB expression group was lower than that in the low-LACTB expression group (P < 0.05, Fig. 1D).

Expression of LACTB in gastric cancer. (A) ChoGastric Statistics study to detect the expression level of LACTB in gastric cancer; (B) Immunohistochemistry to detect the expression of LACTB in para-cancer and cancer tissues(×400); (C) Quantitative analysis of immunohistochemical results; (D) Effect of LACTB expression on survival of patients with tumor diameters greater than 4.5 cm; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Construction of LACTB overexpressing and LACTB knockdown stable transformants

Using the gastric mucosa cell line GES-1 as a control, LACTB mRNA was found to be highly expressed in gastric cancer cell lines AGS (1.30 ± 0.08), MKN-28 (1.46 ± 0.10), and MKN-45 (1.39 ± 0.12) with varying degrees of differentiation (P < 0.05, Fig. 2A). It was poorly expressed in undifferentiated gastric cancer cell line HGC-27 (0.49 ± 0.06) (P < 0.05, Fig. 2A). AGS were infected with an LACTB-overexpressing lentivirus to create a stable AGS overexpressing strain (+ LACTB) alongside a control AGS empty cell strain (Vector1). Compared with Vector1, LACTB mRNA and protein expression in + LACTB was 2.2 times that of Vector1 (P < 0.05, Figs. 2B–D). RNAi lentiviral vectors were used to reduce LACTB expression level in AGS cells, with the LACTB-RNAi (67213-1) knockdown effect being the most significant. Consequently, an AGS empty vector stable strain (Vector 2) and an AGS knockdown stable strain (sh-LACTB) were established. In sh-LACTB cells, LACTB mRNA expression was 28% of Vector 2, while protein expression was 52% (P < 0.05, Figs. 2B–D). These results confirm that the stable AGS cell lines with LACTB overexpression and knockdown were successfully constructed.

mRNA and protein expression levels of LACTB stably transformed strains. (A) Expression level of LACTB mRNA in gastric cancer cell lines; (B) mRNA expression level of LACTB stably transfected lines; (C-D) Protein expression level of LACTB stably transfected lines; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

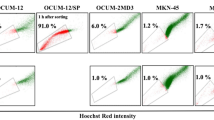

Knockdown of LACTB promotes apoptosis of gastric cancer cells

Stable transfected cell lines and control cells were collected. Annexin V-APC and 7-AAD staining were analyzed by flow cytometry to investigate the effect of LACTB on gastric cancer cell apoptosis. Based on quadrant gating, Q2-4 represented early apoptotic cells, Q2-2 represented late apoptotic cells, and the sum of Q2-4 and Q2-2 is total apoptotic cells. Statistical analysis indicated that in comparison to Vector1 LACTB, overexpression led to a decrease in the proportion of apoptotic cells (P < 0.05, Figs. 3A-B). However, the apoptosis rate increased after knocking down LACTB (P < 0.05, Figs. 3A-B). Western-Blot results further revealed that compared with Vector1, LACTB was overexpressed. The expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bax was downregulated (P < 0.05, Figs. 3C-D), and there was a non-significant difference in the expression of Bcl-2. However, after knocking down LACTB expression, the pro-apoptotic protein Bax was upregulated, and the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was downregulated (P < 0.05, Figs. 3C-D). These results suggest that knocking down the expression level of LACTB can promote apoptosis of gastric cancer cells.

Effect of LACTB on PINK1/Parkin autophagy pathway in gastric cancer cells

Western blotting analysis indicates that compared with Vector1, the expression level of P62 protein in + LACTB cell lines increased, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05, Fig. 4A and E). However, there were statistically non-significant differences in PINK1, Parkin protein expression, and LC3II/LC3I ratio (Fig. 4). However, after knocking down LACTB, the expression levels of PINK1 and Parkin, the characteristic proteins of the autophagy pathway, and the ratio of LC3II/LC3I increased (P < 0.05, Fig. 4), and the expression level of P62 decreased (P < 0.05, Fig. 4E). Additionally, there was a statistically non-significant change in reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the + LACTB cell line, while many ROS were produced in the knockdown LACTB cell line (Fig. 5). The above results suggest that knocking down LACTB can upregulate mitochondrial autophagy levels.

The impact of LACTB on the number of autophagosomes in AGS cells was detected by transmission electron microscopy. Autophagosomes are vacuolar bilayer membrane-like structures containing cytoplasmic components. The results indicated that overexpressing LACTB reduced the number of autophagosomes in AGS cells compared to Vector1 (Fig. 6A-D); knocking down LACTB increased the number of autophagosomes in AGS cells (Fig. 6E-H). Moreover, it is suggested that knocking down LACTB activates autophagy. The above results indicate that the knockdown of LACTB activates mitochondrial autophagy through the PINK1/Parkin pathway.

Effect of LACTB on lysosomal-related proteins in gastric cancer cells AGS

Western blotting results indicated that compared to Vector1, lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2) expression was significantly reduced in AGS cells that overexpressed LACTB (P < 0.05, Fig. 7), but there was no statistical difference in the expression levels of LAMP1, cathepsin B (CTSB), and continuous traumatic stress disorder (CTSD; Fig. 7). After knocking down LACTB, the expression levels of LAMP2, CTSB, and CTSD increased significantly, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05, Fig. 7).

Effect of autophagy inhibitor 3MA on apoptosis of AGS cells

The autophagy level of gastric cancer cells was inhibited by a 5 Mm concentration of 3-MA for 24 h. Western blotting analysis indicated that after adding the autophagy inhibitor 3MA, there was no statistical difference in the expression of apoptotic proteins Bax and Bcl-2 in + LACTB cells (Fig. 8). In contrast, the expression of apoptotic protein Bax was inhibited, and the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 increased in sh-LACTB cells (Fig. 8). Previous experiments suggested that inhibition of LACTB can upregulate the level of mitochondrial autophagy in gastric cancer cells, thereby promoting apoptosis in gastric cancer cells, while the addition of 3-MA restores the effect of LACTB on apoptosis. The results suggest that LACTB regulates apoptosis in gastric cancer cells through autophagy.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of gastric cancer is a complex process involving numerous factors27,28. Despite advancements in medical technology leading to progress in surgical treatment, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy for gastric cancer, overall mortality rates have not significantly declined. Consequently, exploring the pathogenesis of gastric cancer is particularly essential for improving treatment options.

Recent studies have found that LACTB is closely linked to the onset and progression of various tumors13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. This study confirmed that LACTB is highly expressed in gastric cancer tissue, and in patients with tumors greater than 4.5 cm in diameter, high levels of LACTB were associated with poorer prognosis. This may suggest that when tumors are large enough, high levels of LACTB may have an impact on survival. Knocking down LACTB promoted apoptosis in gastric cancer cells, while overexpression of LACTB inhibited it. Interestingly, LACTB induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells by activating endogenous caspase-independent pathways25, while in colon cancer cells, miR-1276 suppresses autophagy by downregulating LACTB, thereby inhibiting apoptosis29. Upregulating LACTB expression can also synergize with docetaxel to enhance apoptosis in lung cancer cells17. Accordingly, LACTB appears to have varied effects on apoptosis across different tumors.

This study found that knocking down LACTB increased the expression of PINK1 and Parkin, decreased P62 expression, enhanced the conversion of LC3I to LC3II, and increased ROS levels and autophagosome formation in gastric cancer cells. Therefore, decreasing the expression level of LACTB may up-regulate mitochondrial autophagy in gastric cancer cells. Conversely, overexpressing of LACTB produced the opposite results, indicating non-significant changes, possibly because LACTB expression in the gastric cancer cell line has reached a specific saturation point. Overexpression of LACTB has little effect on the biological function of gastric cancer cells. Further analysis confirmed that upon LACTB knocking down, expression levels of lysosomal-associated proteins such as LAMP2, CTSB, and CTSD were upregulated; upon LACTB overexpression, these changes were reversed or non-significant. These results suggest that LACTB may influence mitochondrial autophagy in gastric cancer cells through the PINK1/Parkin pathway. Autophagy plays a dual role in tumors; in early tumorigenesis, it inhibits tumor growth, while in advanced stages, it can supply nutrients to tumor cells, aiding their development30,31. However, in the advanced stages of tumor development, autophagy provides nutrients to tumor cells and promotes their growth32,33. Like non-selective autophagy, mitochondrial autophagy is complex and exhibits a “two-faced” nature22. The PINK1/Parkin pathway is a classic regulatory pathway for mitochondrial autophagy. In normal mitochondria, PINK1 enters the mitochondria through mitochondrial targeting sequences and is subsequently degraded. When mitochondria are damaged, PINK1 accumulates in the outer membrane of the mitochondria, recruiting Parkin protein, which triggers a series of cascade reactions that prompt autophagosomes to wrap the damaged mitochondria and complete degradation23. When the mitochondrial membrane potential is disrupted, PINK1 activation alters Parkin’s conformation, promoting its accumulation on the mitochondrial surface and initiating its E3 ubiquitin ligases, especially Parkin. PINK1-dependent acidification changes the Parkin conformation, promoting its accumulation on the mitochondrial surface, and triggers its E3 ligase activity through ubiquitination and phosphorylation of PINK1 and Parkin proteins on the outer mitochondrial membrane, which mediates the occurrence of mitochondrial autophagy34,35,36. First, as a mitochondrial protein, LACTB may bind to PINK1 or Parkin, changing their conformation or stability, thereby affecting the occurrence of mitochondrial autophagy; second, LACTB may indirectly affect the PINK1/Parkin pathway by regulating mitochondrial metabolic states. At the same time, LACTB may also affect the oxidative phosphorylation function of mitochondria and produce excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS)37. Excessive ROS will damage mitochondrial DNA, proteins, and lipids, prompting cells to initiate mitochondrial autophagy to clear damaged mitochondria. To maintain the stability of the intracellular environment. Lysosomes, critical endpoints in autophagy, play a significant role in forming autophagy lysosomes. LAMP1 and LAMP2 are essential for autophagy maturation; loss of these proteins impairs autophagosome maturation, thereby inhibiting autophagy38. Therefore, the results suggest that LACTB may regulate the level of mitochondrial autophagy in gastric cancer cells through the PINK1/Parkin pathway and affect the apoptosis of gastric cancer cells, which may promote the occurrence and development of gastric cancer through this pathway in conjunction with other mechanisms.

In this study, gastric cancer cell lines were treated with the autophagy inhibitor 3-MA. The results indicated a non-significant change in Bax and Bcl-2 expression proteins in gastric cancer cells that overexpressed LACTB. In contrast, the expression of Bax was suppressed and the expression of Bcl-2 increased in gastric cancer cells that knocked down LACTB. The results indicate that 3-MA can reduce LACTB-induced apoptosis in gastric cancer cells. Autophagy and apoptosis can be mutually antagonistic or reinforcing; moderate autophagy supports cell survival by providing energy and inhibiting apoptosis, whereas excessive autophagy is present, and autophagy promotes the transformation of cells toward apoptosis39,40. Apoptosis can be achieved through endogenous and exogenous pathways41, with the endogenous pathway involving mitochondria proteins with pro-apoptosis functions42. For instance, silybin induces apoptosis in MCF7 breast cancer cells by regulating autophagy, reducing mitochondrial membrane potential, and increasing ROS levels43. Ketoconazole induces apoptosis in liver cancer cells by downregulating COX-2 and activating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitochondrial autophagy, thus inhibiting liver cancer cell growth44. Likewise, 8-paradol activates PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitochondrial autophagy and induces apoptosis in gastric cancer cells45. Additionally, LACTB promotes radioresistance in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by activating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitochondrial autophagy in these cells46. Consequently, we concluded that the LACTB knockdown in gastric cancer cells may promote apoptosis by activating the PINK1/Parkin mitochondrial autophagy pathway.

In summary, LACTB may modulate the tumor cell apoptosis by regulating the PINK1/Parkin mitochondrial autophagy pathway in gastric cancer, a finding with significant clinical implications. For patients with single gastric cancer, further experiments can be carried out to explore drugs that inhibit LACTB expression and verify whether it is possible to combine them with autophagy activators for preoperative adjuvant treatment of patients with gastric cancer. Provide a better opportunity for surgery for patients with gastric cancer, or create surgical conditions for patients who cannot undergo surgical treatment. This pathway could serve as a potential entry point for targeted treatment of patients with gastric cancer, warranting further in-depth investigation in future research.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings in this study are available within the manuscript. Any further details will be available upon request. Please contact Dr. Yang Fang, 18798082303@163.com.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74 https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 229-74263. (2024).

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: an overview. Int. J. Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33588 149,778–789. (2021).

Cao, W. et al. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in china: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 134, 783–791. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000001474( (2021).

Xia, C. et al. Cancer screening in china: a steep road from evidence to implementation. Lancet Public. Health. 8, e996–e1005. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00186-X (2023).

Sexton, R. E., Hallak, A., Diab, M. N. & Azmi, A. S. M. Gastric cancer: a comprehensive review of current and future treatment strategies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 39, 1179–1203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-020-09925-3 (2020).

Smyth, E. C., Nilsson, M., Grabsch, H. I., van Grieken, N. C. & Lordick, F. Gastric cancer Lancet 396, 635–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31288-5 (2020).

López, M. J. et al. Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 181, 103841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103841 (2023).

Bollschweiler, E., Berlth, F., Baltin, C., Mönig, S. & Hölscher, A. H. Treatment of early gastric cancer in the Western world. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 5672–5678. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5672 (2014).

Das, M. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy: survival benefit in gastric cancer. Lancet Oncol. 18, 307. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30321-2 (2017).

Tan, Z. Recent advances in the surgical treatment of advanced gastric cancer: A review. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 3537–3541. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.916475 (2019).

Peitsaro, N. et al. Evolution of a family of metazoan active-site-serine enzymes from penicillin-binding proteins: a novel facet of the bacterial legacy. BMC Evol. Biol. 8, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-8-26 (2008).

Keckesova et al. LACTB is a tumour suppressor that modulates lipid metabolism and cell state. Nature 543, 681–686. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21408 (2017).

Xue, C. et al. Low expression of LACTB promotes tumor progression and predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Transl Res. 10, 4152–4162 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Upregulation of miR-374a promotes tumor metastasis and progression by downregulating LACTB and predicts unfavorable prognosis in breast cancer. Cancer Med. 7, 3351–3362. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1576 (2018).

Zeng, K. et al. LACTB, a novel epigenetic silenced tumor suppressor, inhibits colorectal cancer progression by attenuating MDM2-mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation. Oncogene 37, 5534–5551. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-021-01795-5 (2018).

Li, H. T., Dong, D. Y., Liu, Q., Xu, Y. Q. & Chen, L. Overexpression of LACTB, a mitochondrial protein that inhibits proliferation and invasion in glioma cells. Oncol. Res. 27, 423–429. https://doi.org/10.3727/096504017X15030178624579 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. LACTB suppresses carcinogenesis in lung cancer and regulates the EMT pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 23, 247–258. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2022.11172 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Targeted nanotherapeutics using LACTB gene therapy against melanoma. Int. J. Nanomed. 16, 7697–7709. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S331519 (2021).

Peng, L. X. et al. LACTB promotes metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via activation of ERBB3/EGFR-ERK signaling resulting in unfavorable patient survival. Cancer Lett. 498, 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2020.10.051 (2021).

Xie, J. et al. LACTB mRNA expression is increased in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and high expression indicates a poor prognosis. PLoS One. 16, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245908 (2021).

Nie, W. et al. A potential therapeutic approach for gastric cancer: Inhibition of LACTB transcript 1. Aging (Albany NY). 15, 15213–15227.https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.205345 (2023).

Picca, A., Faitg, J., Auwerx, J., Ferrucci, L. & D’Amico, D. Mitophagy in human health, ageing and disease. Nat. Metab. 5, 2047–2061. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-023-00930-8 (2023).

Lazarou, M. et al. The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature 524, 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14893 (2015).

Liu, S. et al. Regulator of cell death. Cell. Death Dis. 14, 648–665. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-023-06154-8(2023).

Gonzalez-Morena, J. M. et al. LACTB induces cancer cell death through the activation of the intrinsic caspase-independent pathway in breast cancer. Apoptosis 28, 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10495-022-01775-4 (2023).

Jaffer, S., Orta, L., Sunkara, S., Sabo, E. & Burstein, D. E. Immunohistochemical detection of antiapoptotic protein X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis in mammary carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 38, 864–870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2006.11.016 (2007).

Ma, Y. et al. Current development of molecular classifications of gastric cancer based on omics (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 65, 89. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.( (2024).

Christodoulidis, G., Koumarelas, K. E., Kouliou, M. N., Thodou, E. & Samara, M. Gastric Cancer in the era of epigenetics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 3381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25063381 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. MicroRNA-1276 promotes Colon cancer cell proliferation by negatively regulating LACTB. Cancer Manag Res. 12, 12185–12195. https://doi.org/0.2147/CMAR.S278566 (2020).

Debnath, J., Gammoh, N. & Ryan, K. M. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 560–575. https://doi.org/0.1038/s41580-023-00585-z (2023).

Barnard, R. A. et al. Autophagy Inhibition delays early but not Late-Stage metastatic disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 358, 282–293. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.116.233908 (2016).

Dikic, I. & Elazar, Z. Mechanism and medical implications of mammalian autophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-018-0003-4 (2018).

Fitzwalter, B. E. et al. Autophagy inhibition mediates apoptosis sensitization in cancer therapy by relieving FOXO3a turnover. Dev Cell. 44, 555–565. (2018).

Harper, J. W., Ordureau, A. & Heo, J. M. Building and decoding ubiquitin chains for mitophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 93–108. (2017).

Sarraf, S. A. et al. Landscape of the PARKIN-dependent ubiquitylome in response to mitochondrial depolarization. Nature 496, 372–376. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12043 (2013).

Chen, Y. & Dorn, G. W. PINK1-phosphorylated Mitofusin 2 is a parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science 340, 471–475. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1231031 (2013).

Xiao, Y. Y. et al. Metformin-induced AMPK activation promotes cisplatin resistance through PINK1/Parkin dependent mitophagy in gastric cancer. Front. Oncol. 12, 956190. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.956190 (2022).

Tanaka, Y. et al. Accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and cardiomyopathy in LAMP-2-deficient mice. Nature 406, 902–906. https://doi.org/0.1038/35022595 (2000).

Prerna, K. & Dubey, V. K. Beclin1-mediated interplay between autophagy and apoptosis: new Understanding. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 204, 258–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.02.005(2022).

Deng, H. et al. Itraconazole inhibits the Hedgehog signaling pathway thereby inducing autophagy-mediated apoptosis of colon cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 11, 539–554. https;//doi.org/0.1038/s41419-020-02742-0 (2020).

Chaudhry, G. E., Akim, A. M., Sung, Y. Y. & Muhammad, T. S. T. Cancer and apoptosis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2543, 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2553-8_16( (2022).

Braicu, C. et al. Natural compounds modulate the crosstalk between apoptosis- and autophagy-regulated signaling pathways: controlling the uncontrolled expansion of tumor cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 80, 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.05.015(2022).

Jiang, K. et al. Silibinin, a natural flavonoid, induces autophagy via ROS-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction and loss of ATP involving BNIP3 in human MCF7 breast cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 33, 2711–2718. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2015.3915 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Ketoconazole exacerbates mitophagy to induce apoptosis by downregulating cyclooxygenase-2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 70, 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.022 (2019).

Wang, R. et al. 8-paradol from ginger exacerbates PINK1/Parkin mediated mitophagy to induce apoptosis in human gastric adenocarcinoma. Pharmacol. Res. 187, 106610–106625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106610 (2023).

Chen, Q. et al. LACTB2 renders radioresistance by activating PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 518, 127–139. https://doi.org/0.1016/j.canlet.07.019, (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the supports from Guizhou Medical University.

Funding

This study was supported by the Doctoral Startup Fund of Guizhou Medical University (No. [2021]043) ,Doctoral Startup Fund of the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University (No. gyfybsky-2021-66) and Guizhou Provincial Basic Research Program(Natural Science) (Qiankehe foundation zk[2024] general 196).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FY designed the study. WN, LH, ZY, QW, SH, and XG performed data analysis. WN and LH drafted the manuscript. FY revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University. And informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). All tissue specimens collected for this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations established by the ethics committee(Approval Letter No.: 2021 Ethics No. 030, Human Trials Ethics Committee of Guizhou Medical University.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nie, W., Hu, L., Yan, Z. et al. Study on the regulation of gastric cancer cell apoptosis by LACTB through mitochondrial autophagy pathway. Sci Rep 15, 23273 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06047-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06047-0