Abstract

Soil respiration (RS) comprises terrestrial ecosystems’ second-largest carbon flux. Yet, methodological errors in RS partitioning and uncertainties in seasonal responses of RS make it difficult to predict future RS. Here, we tested the assumption of RS partitioning (similar microbial respiration between planted and root-free soils), and explored two components of RS, autotrophic and heterotrophic respiration (RA, RH, respectively), in a temperate grassland under monsoon continental climate. Microbial respiration in soils from planted plots was 3.88 times higher than that from root-free plots during lab incubation. In field, RH:RS ratio was relatively low during non-monsoon, but increased during monsoon. The RH was more sensitive to temperature than RS, indicating a greater Q10 of RH than that of estimated RA. The annual RH:RS excluding the monsoon period was comparable to those reported in the global Soil Respiration Database (SRDB) and other Korean literature. This study highlights that the assumption of RS partitioning can be violated, that RH exhibits a greater sensitivity to changes in temperature and soil water content than RA, and that annual RH:RS may be similar across the globe when extreme precipitation (e.g., monsoon) is excluded.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil respiration (RS) is the CO2 release from soil to the atmosphere via autotrophic respiration (RA, roots and mycorrhizal fungi) and heterotrophic respiration (RH, saprotrophic microbes)1,2. On a global scale, RS releases approximately 110 Pg C to the atmosphere annually3,4, representing the second largest carbon (C) flux in terrestrial ecosystems5. Despite the substantial magnitude of RS the seasonal variability of RS makes it difficult to accurately predict RS6,7,8. This is because we still have limited knowledge about how RS will respond to changes in soil temperature and water content, a common condition especially in a monsoon climate, and how the partitioning of RS into RA and RH will change with seasons9,10. Given that 19.4% of Earth’s surface exhibits monsoon climates and that extreme temperature and precipitation regimes are expected to increase under future climate scenarios11,12, it is necessary to explore RA, RH, and RS with changes in temperature and water content to improve the accuracy of future climate projections.

Soil temperature and water content can differentially influence RA, RH, and RS2,13. While increasing temperature enhances the rates of biochemical reactions, temperature sensitivity (Q10; the change in the reaction rate with a 10 °C increase in temperature) can vary with the types of reactions. For example, Q10 of RH is reported from 1.43 to 5.4814,15, while that of RS is between 1.07 and 6.6016. Different biochemical reactions involved in RA and RH can lead to the differences in the Q10. RA is influenced by plant phenology and the photosynthate allocation to roots17,18. In contrast, RH is influenced by substrate availability, microbial physiological responses, microbial C demand, and community composition19.

Soil water content can also influence RH and RS by altering substrate availability and microbial physiological responses20,21,22. At relatively low soil water content, microbial metabolic activity can be restricted due to reduced diffusion of organic C (OC)23. When precipitation falls, relatively high soil water content can induce CO2 pulses from soils, via OC dissolution and diffusion, promotion of the release of cellular metabolites, and stimulation of microbial activity24,25. As such, shifts in OC availability and microbial physiological responses upon changes in soil water content should be accounted for when exploring RS in regions with huge fluctuations in rainfall over seasons. Specifically, Korea’s climate is classified as a monsoon continental climate, with heavy rainfall occurring in summer. The summer monsoon can lead to rapid increases in soil water content and trigger the CO2 pulses from soils, known as the “birch effect”26,27,28. So far, only few studies have explored how the partitioning of RS into RA and RH will change with rapid changes in soil water content29,30. For example, RA responds to heavy rainfall more slowly than RH29, partly because a suite of conditions, such as CO2 level and light intensity, can also influence RA as well as water availability31.

Root exclusion is commonly used to partition RS into RA and RH32,33. This approach either uses bare plots (bare soil method) or cuts live roots around plots (trenching method), to prevent roots from respiring newly produced photosynthates33,34. Neither the bare soil nor trenching method determines RA directly. Instead, both methods estimate RA by subtracting RH from RS35. The assumption behind this calculation is that microbial respiration from the root-free plots is the same as microbial respiration from the intact, planted plots36. However, this assumption has rarely been explicitly tested, raising concerns about the accuracy of RA and RH estimation. The presence and activity of roots often stimulate microbial respiration and growth in the rhizosphere37. If this holds true, microbial respiration from the root-free plots should be lower than that from planted plots, therefore decreasing the accuracy of RA estimation.

Here, we explore how seasonal temperature and water content variations influence RH and RS in a grassland under a monsoon continental climate, a relatively less studied ecosystem and climate, to obtain a more detailed RS assessment. Also, we compared our RH:RS ratio to those from the global Soil Respiration Database (SRDB)38 and domestic forest data (published in Korean, so not included in the SRDB) to evaluate the generalizability of our results and to better constrain regional soil C dynamics. Finally, we tested the assumption of root exclusion methods that microbial respiration is similar between root-free and planted plots. We hypothesized that (1) microbial respiration will be higher in planted plots than in root-free plots, (2) RH will respond to seasonal variations in temperature and water content to a greater degree than RA, and (3) the average RH:RS ratio in this study will differ from those reported worldwide in the SRDB.

Results

Initial soil physicochemical and microbial properties

Before the field measurement of RS and RH, we characterized initial soil physicochemical and biological properties in the M. × giganteus and M. × giganteus-free soils. Soil physicochemical characteristics were similar between the M. × giganteus and M. × giganteus-free soils, except for sand and silt contents (Table 1). The K2SO4-extractable OC tended to be greater in the M. × giganteus soils compared to the M. × giganteus-free soils (p = 0.114).

The M. × giganteus soils harbored more root biomass and microbial biomass C compared to M. × giganteus-free soils (Table 1). Microbial respiration assessed in the laboratory was 287.50% higher in the M. × giganteus soils compared to the M. × giganteus-free soils (p < 0.001, Fig. 1). Microbial respiration was significantly correlated with microbial biomass C and K2SO4-extractable OC (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.71, p < 0.001 for microbial biomass C; r = 0.74, p = 0.04 for K2SO4-extractable OC).

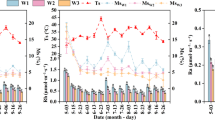

Seasonal soil temperature, water content, RH, and RS

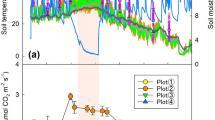

We assessed soil temperature, soil volumetric water content, RH and RS between May and December in 2023. Soil temperature was similar between the M. × giganteus and M. × giganteus-free plots over the whole study period (Fig. 2a). The summer monsoon occurred from June 25th to July 26th, when soils received 50% of the annual precipitation (179.80% of the 30-year average monsoon period rainfall)39. Soil water content was significantly higher in the M. × giganteus plots than the M. × giganteus-free plots during the summer monsoon (p = 0.001), but was similar in other periods (Fig. 2b). Both RH and RS exhibited significant seasonal variability (p < 0.001 for both), with the monthly average RH:RS ratio ranging from 0.35 to 1.12 (Table 2). While RH was lower than RS during the non-monsoon period, RH exceeded RS during the monsoon period when soil water content was relatively low in the M. × giganteus-free plots (Fig. 3 and Fig. 2b).

Seasonal variations of (a) soil temperature and (b) soil volumetric water content at a depth of 6 cm, and precipitation in M. × giganteus and M. × giganteus-free plots from April 2023 to December 2023. The shaded area represents the monsoon period from June 25th to July 26th, 2023. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (n = 4).

To clarify the seasonal variability of RH and RS, we performed a nonlinear model analysis with CO₂ flux as a dependent variable, and temperature and water content as explanatory variables (Table 3). During the non-monsoon period, both soil temperature and water content significantly influenced RH and RS (Table 3, Fig. 4a and 4b). In contrast, we did not find significant effects of temperature and water content on RH and RS during the monsoon period (Table 3, Fig. 4c and 4d). When we plotted CO₂ flux as a function of soil temperature, RS and RH were relatively well explained by soil temperature (R2 = 0.81 and 0.54, respectively), with Q10 values of 2.29 and 2.67 for RS and RH (Fig. 5).

Response surface showing the relationships between soil temperature (°C) and soil volumetric water content (m3 m−3) with: (a) soil respiration (RS) during non-monsoon period, (b) heterotrophic respiration (RH) during non-monsoon period, (c) RS during monsoon period, and (d) RH during monsoon period. Observed values (black dots) represent measured soil CO2 flux, and modeled values (colored surfaces) are predictions derived from fitted to the observations.

The relationships between soil CO2 flux and soil temperature (T, °C) in the M. × giganteus and M. × giganteus-free plots using observed whole data over the non-monsoon period. The red and blue dashed lines indicate the exponential curves of RH (heterotrophic respiration) and RS (soil respiration) with soil temperature, respectively.

Comparison of RH:RS ratio

We compared our RH:RS ratio to those reported in Korean literature and the SRDB-V5 (Fig. 6 and Table 4). The average RH:RS ratio during the non-monsoon in this study was comparable to the average RH:RS ratio from only one grassland study in Korea (Table 4) and from other ecosystems worldwide (SRDB-V5 data, Fig. 6). In contrast, the average RH:RS ratio during the entire period including the monsoon was higher than the RH:RS ratio reported in the SRDB-V5 (Fig. 6).

The ratio of heterotrophic respiration to soil respiration across ecosystem types. Data are drawn from a global Soil Respiration Database (SRDB) and our study site. Linear regression lines were fitted to each ecosystem type, with forest in solid green (y = 0.51x + 47.19, R2 = 0.62), grassland in solid blue (y = 0.47x + 60.98, R2 = 0.71), agriculture in solid purple (y = 0.42x + 78.78, R2 = 0.37), this study during the non-monsoon period in solid pink (y = 0.79x – 267.13, R2 = 0.68), and this study during the entire period in dashed pink (y = 1.04x – 333.83, R2 = 0.71).

Discussion

Laboratory measurement of microbial respiration in the M. × giganteus soils and M. × giganteus-free soils

Consistent with our first hypothesis, microbial respiration was higher in the M. × giganteus soils compared to the M. × giganteus-free soils (Fig. 1). Greater microbial biomass C and respiration in the M. × giganteus soils (Fig. 1 and Table 1) suggest that roots have stimulated soil microbial activities. Living roots release approximately 5–21% of the total C fixed through photosynthesis via root exudates40,41. This release of easily available OC likely contributes to the enhanced microbial activities in M. × giganteus soils. Indeed, we observed relatively higher concentration of K2SO4-extractable OC in the M. × giganteus soils (Table 1). Dissolved organic carbon (DOC), a primary C substrate for microorganisms42,43, is positively correlated with microbial respiration (RH)43. In line with these studies, we observed a significant positive correlation between K2SO4-extractable OC and microbial respiration (p = 0.04). Thus, our results imply that microbial communities in the M. × giganteus soil had greater access to easily available OC than those in the M. × giganteus-free soils, and that the presence of M. × giganteus roots likely stimulates microbial activity via root exudates.

Our findings that microbial respiration differed between plots with or without M. × giganteus have implications for the interpretation of RH and RA in RS partitioning. Traditionally, root exclusion methods assume that microbial respiration from planted and root-free soils is identical33. Yet, some studies reported that the assumption can be violated if the decomposition of dead fine roots in trenched soils causes an overestimation in RH32,34. While our finding is similar to these studies in that microbial respiration differs between planted and root-free soils, we demonstrate that RH is likely to be underestimated, not overestimated, in the bare soil method. This is because the bare soil method did not involve cutting live roots. Some dead roots found in these plots were likely debris from long-deceased plants that had previously occupied the M. × giganteus-free plots, and therefore cannot promote microbial respiration (no overestimation of RH). Previous studies report that RS partitioning method can influence the estimation of RH and RA, potentially introducing biases in CO₂ flux calculations34,44. This along with our results highlights the need to interpret results within the context of methodological choices in RS partitioning, to improve the accuracy of soil CO₂ flux estimation and better predict ecosystem C dynamics.

We acknowledge that we measured microbial respiration once in the laboratory in mid-June, and that we do not know how much microbial respiration would vary with seasons. However, the peak season of plant growth is from July to August, during which rapidly growing plants release more root exudation and thus more DOC45,46. Given that our sampling was conducted in mid-June when root exudates might have been less abundant compared to the peak of plant growth, soils sampled during this period may have lower microbial respiration than those sampled in July and August. This suggests that microbial respiration may be underestimated to a greater extent than we proposed.

Field RH and RS over seasons

Our results supported the second hypothesis that RH is more sensitive to seasonal variations in temperature and water content than RA. Relatively high Q10 of RH and the RH:RS ratio (Fig. 5 and Table 2) indicate greater responses of RH than RA to seasons. The greater seasonal response of RH than RA can be explained in two ways. First, respiratory substrates differ between RA and RH. In the M. × giganteus-free plots, labile C inputs (i.e., fresh litter, root exudates) are absent, prompting microbes to respire relatively old and complex C compounds. In contrast, roots respire fresh carbohydrates derived from photosynthesis47,48. The Arrhenius equation dictates that complex compounds require greater activation energy for the reaction to proceed, resulting in higher Q10 values49,50,51. As such, RH derived from relatively old and complex C compounds can exhibit a greater Q10 than RA.

Second, while temperature and water are the two most important factors for heterotrophic respiration, other environmental factors such as radiation intensity and nutrient availability can also affect autotrophic respiration. High temperature and water availability during the summer monsoon greatly enhanced heterotrophic respiration (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Yet, autotrophic respiration may have suffered from a lack of radiation and associated reductions in photosynthesis31,52,53. In fact, a more rapid increase in RH with rising temperature compared to RA has been observed in other studies when water is not limiting29,53,54.

Interestingly, during the monsoon period, the RH was higher than RS (Fig. 3) and soil water content was lower in the M. × giganteus-free plots compared to the M. × giganteus plots (Fig. 2b). These observations deviate from the common expectation: higher RS than RH and greater soil water content in root-free soils due to no plant water uptake32. We ascribe our observations to the litter accumulation and saturation of soil pores. In the M. × giganteus plots, the dead shoots from previous years have accumulated on soil surface, likely decreasing evaporation from soil to the atmosphere. Also, we frequently observed the formation of puddles in the M. × giganteus plots during the monsoon. This was because the accumulated litterfalls and overshooting rhizomes promoted microtopography conducive to waterlogging. In contrast, heavy rainfall during the monsoon may have directly infiltrated soil in the M. × giganteus-free plots, facilitating the diffusion of soluble C and the release of intracellular osmolytes55. This influx of readily available substrates likely stimulated microbial activity, fueling the observed pulse of RH in M. × giganteus-free plots. Combined, litter accumulation and waterlogging seemed to inhibit O2 diffusion and RS, while rapid rainfall infiltration facilitated substrate availability and enhanced RH, ultimately causing RH to exceed RS during the monsoon.

Comparisons of RS and RH among ecosystems

Our third hypothesis that the RH:RS ratio will differ between our data and the SRDB was partly supported. During monsoon, the RH:RS ratio in this study was greater than the world RH:RS ratio (Fig. 6). Yet, during non-monsoon, the RH:RS ratios were similar among literatures. For example, the annual mean RH:RS was 0.59 in forests, 0.57 in grasslands, and 0.62 in agriculture ratio in the SRDB, which were similar to the RH:RS ratio from Korean literature (Table 4). Similar RH:RS ratio across ecosystems and between Korea and world data imply that it may be feasible to use global RH:RS ratio to fill the ecosystem gap with little data. Furthermore, the global similarity of RH:RS ratio when extreme precipitation is excluded highlights the importance of considering rainfall variability of monsoon climate in soil C dynamics. These findings indicate that extreme monsoon rainfall significantly influences the RH:RS ratio, and that neglecting this variability may lead to biases in soil C dynamics modeling in monsoon regions. Therefore, integrating extreme rainfall variability into predictive models is essential for accurately quantifying soil CO2 fluxes and better capturing the spatial and temporal patterns of the RH:RS ratio.

Conclusions

We demonstrate significant variability in RS, RH, and the RH:RS ratio across seasons under continental monsoon climate. Our results highlight that RH is more sensitive to changes in temperature and soil water content than RA. Also, our observation of lower microbial respiration in root-free soils emphasizes the need to carefully consider RS partitioning methods for accurately estimating and predicting CO2 flux from plants and soil in terrestrial ecosystems. Furthermore, relatively similar RH:RS ratios during non-monsoon across ecosystems suggest the possibility of employing world data to estimate RH from less-studied ecosystems or regions. Notably, the significant increase in RH:RS during the monsoon highlights the strong influence of extreme rainfall events on soil respiration dynamics. Further studies are required to gain a deeper mechanistic understanding of the long-term or cumulative effects of extreme summer monsoon rainfall and temperature in a monsoon continental climate across various ecosystems. Additionally, to improve the accuracy of C flux estimations, predictive models should account for biases in RH and RA arising from different partitioning methods and consider extreme rainfall variability. Incorporating these factors will enable more precise C flux predictions and facilitate a more consistent observation of global RH:RS ratio trends.

Materials and methods

Site description

This study was conducted at the Experimental Farm of Seoul National University, Suwon, Korea (37°16′ 12.598" N, 126° 59′ 24.529" E). The region experiences a monsoon continental climate, with four distinct seasons including hot and humid summers and cold winters. The 10-year mean annual temperature is 13.04 °C, with the minimum daily mean temperature of −6.7 °C in January and a maximum of 31.2 °C in August. The mean annual precipitation is 1,320 mm, falling primarily between June and July during the summer monsoon period (https://data.kma.go.kr/cmmn/main.do).

In 2011, twenty Miscanthus × giganteus plots were established to study plant-soil C interactions and use M. × giganteus as biofuel production. We selected M. × giganteus due to its extensive rhizome and root biomasses, which drive belowground C cycling56. The M. × giganteus plots are part of a long-term Nitrogen (N) addition with 0, 30, 60, 120, and 240 kg N ha−1 year−1 (total 20 plots = 5 N treatments × 4 replicates, 2 m × 4 m each). Each plot was housed in a 1.64 m deep lysimeter and separated from one another. Among the M. × giganteus plots, we only used the control plots (0 kg N ha−1 year−1) for this study.

The bare soil method was used to partition RS into RA and RH. We leveraged the M. × giganteus plots in a separate lysimeter to measure RS and considered M. × giganteus-free soils outside the lysimeter as bare, root-excluded plots (hereafter M. × giganteus-free plots, n = 4) to measure RH. We regularly removed any plants growing in the M. × giganteus-free plots by pulling them out to minimize root respiration.

Soil sampling and initial physicochemical properties

In June 2023, we collected surface soils (0–10 cm depth) from the M. × giganteus plots and M. × giganteus-free plots using a Gas-powered core sampler (AMS Inc., USA) with a PVC tube liner (inner diameter: 3.81 cm) and a soil auger (0–6 cm depth), respectively. A total of 8 soil cores (2 treatments * 4 replicates) were promptly stored in a cooler at 4 °C, passed through a 2 mm sieve, and transferred to the laboratory at Seoul National University. We collected roots larger than 2 mm from each soil core, oven-dried at 55 °C for 2 days, and recorded the weights. Soil pH was determined on 1:5 (w/v) soil:water slurry (S220, Mettler Toledo, Switzerland). Gravimetric water content was assessed by drying 5 g soils at 105 °C for 48 h. We assessed water holding capacity by saturating 10 g of soil with 25 mL of deionized water and draining it for 4 h using a filter funnel (Qualitative filter papers no.1, Whatman™, UK). Total C and N were measured on sieved, 105 °C dried, finely-ground soils at the National Instrumentation Center for Environmental Management (NICEM), Seoul National University. K2SO4-extractable OC was quantified by mixing a 5 g soil sample with 25 mL of 0.5 M K2SO4 and shaking the mixture at 200 rpm for 4 h. Subsequently, the slurries were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min (MF-600 plus, Hanil, Korea), and then filtered using 0.45 μm pore-size vacuum filtration (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). The total amount of OC in the K2SO4 extracts was then analyzed using a total OC analyzer (TOC-L, SHIMADZU, Japan) at the NICEM. Bulk density was calculated as the dry weight of soil divided by its total soil sample volume after correcting rock volume and weight. We determined particle size distribution using the hydrometer method.

Lab measurement of microbial respiration and substrate-induced respiration (SIR)

To quantify this important thing that links to our hypothesis (microbial respiration would be higher in root-containing plots than in root-free plots), we used sieved soils to assess microbial respiration and microbial biomass C in soils with or without plant roots in the laboratory. Following Min et al.57, we placed 10 g of fresh soil in 400 mL jars and pre-incubated them at 22 °C overnight (8 jars = 2 treatments * 4 replicates). The jars were sealed with a lid equipped with a non-dispersive infrared CO2 sensor (K30-FS 10,000 ppm sensor, CO2 meter). We measured CO2 concentration every 30 s for 15 min, calculated the slope of the CO2 flux, and repeated this for 2 h (thus 6 times of measurements of CO2 flux). The microbial respiration rate was expressed as μg C-CO2 g−1 dry soil h−1.

Once microbial respiration rate was assessed, we added 400 mg of powdered yeast extract (Yeast Extract, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) to the jars as a C and nutrient source and adjusted water content to 60% of water holding capacity. The CO2 concentration in the jar was recorded every 30 s for 15 min, and this measurement was repeated 8 times (substrate-induced respiration, SIR). We then calculated the average SIR in μg C-CO2 g−1 dry soil h-1 and converted it to microbial biomass C following Anderson and Domsch58.

The average microbial biomass C over the entire measurement period served as an index of the SIR-responsive microbial biomass C pool.

Field measurement of RS and RH, and the Q 10 of RS and RH

We also assessed field respiration from the M. × giganteus plots and the M. × giganteus-free plots (hereafter, RS and RH, respectively). In the field, PVC collars (outside diameter: 11.4 cm, height: 7.5 cm) were randomly inserted into the M. × giganteus plots and the M. × giganteus-free plots (n = 4, each) at a depth of 3 cm in early May 2023. All collars were fixed in the same position in the plots during the entire experiment. To eliminate the influence of above-ground plant respiration, small living plants inside the collars were clipped, and the litter within the collar was removed before the measurements of CO2 fluxes. Soil CO2 fluxes were measured once or twice every month from May to December in 2023 using the EGM-5 infrared gas analyzer (PP systems, USA) connected to the SRC-2 soil respiration chamber. The CO2 fluxes in the field data were derived from the slope of the linear increase in the CO2 concentration over the sampling time, calculated as follows:

, where \(dC\) is the variation in CO2 concentration (ppm), \(dT\) is the process execution time (s), \(P\) is the air pressure (atm), \(V\) is the chamber volume (L), \(A\) is the area of soil enclosed by the chamber, \(R\) is the ideal gas constant (0.082 L atm mol−1 K−1), and \(T\) is the soil temperature (K). Soil temperature and soil volumetric water content were measured at a depth of 0–6 cm using Stevens Hydra Probe (PP systems, USA) concomitantly with the probe inserted adjacent to the collar during the soil CO2 flux measurements. The RH:RS ratio was calculated for each measurement day and averaged every month.

To quantify the relationships between soil CO2 flux and the interaction of soil temperature and soil water content, nonlinear models were fitted using the following equation59.

, where \(F{\text{CO}}_{2}\) measured soil CO2 fluxes (μg C cm⁻2 h⁻1), \(W\) is soil water content (m3 m−3), \(T\) is the soil temperature (°C), and \({\gamma }_{1}\), \({\gamma }_{2}\), and \({\gamma }_{3}\) are the fitted model coefficients.

An exponential model was used to examine the responses of soil CO2 fluxes to soil temperature1:

, where \(FC{O}_{2}\) measured soil CO2 fluxes (g C m−2 yr−1), \(T\) the soil temperature (°C), the coefficient α is the soil CO2 flux at a reference temperature of 0 °C, and β is the sensitivity of soil CO2 flux to soil temperature. The β value was used to calculate the Q10 value. Note that we calculated Q10 for the non-monsoon period only, as the temperature range during the monsoon period was not wide enough to calculate Q10.

World and Korea literature search

We retrieved RS and RH data from the 5.0 version of the SRDB (SRDB-V5) (downloaded on 30 October 2023 from https://daac.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/dsviewer.pl?ds_id=1827). This comprehensive database collects a broad spectrum of field-measured soil respiration data from 1961 to 2017, incorporating over 2,266 published studies and 10,366 individual records. For soil respiration analysis, we used data that met specific criteria (i) inclusion of both annual RS and RH, (ii) RH:RS ratios between 0 to 1, (iii) no manipulations such as fertilization or CO2 enrichment, and (iv) data from forests, grasslands, and agricultural study sites only. The number of data for each ecosystem was as follows: forests (total n = 514; including deciduous forest, n = 202 and evergreen forest, n = 312), grasslands (n = 70), and agricultural lands (n = 48).

Also, we compiled RS and RH data from Korean literature using the keywords “soil respiration”, “heterotrophic respiration”, “autotrophic respiration” and “trenching” in the Korean Citation Index, Google Scholar, and Research Information Sharing Service (Supplementary 1). 256 data points were extracted from 9 articles using Web Plot Digitizer (https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/). These data were compiled with specific criteria similar to SRDB, covering forests (n = 255), grassland (n = 1), and agriculture (n = 0).

Statistical analyses

We conducted the Shapiro–Wilk test to check if data are normally distributed. The initial biological and physicochemical properties in the M. × giganteus and M. × giganteus-free soil samples were compared by using independent sample t-tests. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare root biomass between the M. × giganteus and M. × giganteus-free soils. We used Spearman correlation to determine the relationship between microbial biomass C and soil CO2 flux, and Pearson correlation for microbial biomass C and K2SO4-extractable OC. Additionally, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the SRDB and Korean data, and to examine the differences in the RS and RH across different ecosystems. Two-way ANOVA was used to assess the effects of root exclusion and time on microbial respiration, soil CO2 flux, soil temperature, and soil water content. All statistical analyses were performed using R 4.3.1, with statistical significance set at p = 0.0560.

Data availability

The data in this study are available upon request. Please contact Hyunjin Kim (hj991209@snu.ac.kr) for more information.

References

Lloyd, J. & Taylor, J. A. On the temperature dependence of soil respiration. Funct. Ecol. 8, 315–323 (1994).

Li, Y., Xu, M. & Zou, X. Heterotrophic soil respiration in relation to environmental factors and microbial biomass in two wet tropical forests. Plant Soil 281, 193–201 (2006).

IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C.

Nissan, A. et al. Global warming accelerates soil heterotrophic respiration. Nat. Commun. 14(1), 3452 (2023).

Schlesinger, W. H. & Andrews, J. A. Soil respiration and the global carbon cycle. Biogeochemistry 48, 7–20 (2000).

Boone, R. D., Nadelhoffer, K. J., Canary, J. D. & Kaye, J. P. Roots exert a strong influence on the temperature sensitivityof soil respiration. Nature 396(6711), 570–572 (1998).

Yiqi, L. & Zhou, X. Soil respiration and the environment (Elsevier, 2010).

Zhang, Q., Lei, H. M. & Yang, D. W. Seasonal variations in soil respiration, heterotrophic respiration and autotrophic respiration of a wheat and maize rotation cropland in the North China plain. Agric. For. Meteorol. 180, 34–43 (2013).

Rodtassana, C. et al. Different responses of soil respiration to environmental factors across forest stages in a Southeast Asian forest. Ecol. Evol. 11(21), 15430–15443 (2021).

Lee, E. H., Lim, J. H. & Lee, J. S. A review on soil respiration measurement and its application in Korea. Korean J. Agri. Forest Meteorol. 12(4), 264–276 (2010).

Sadhwani, K. & Eldho, T. I. Assessing the effect of future climate change on drought characteristics and propagation from meteorological to hydrological droughts—a comparison of three indices. Water Resour. Manage 38(2), 441–462 (2024).

Donat, M. G., Lowry, A. L., Alexander, L. V. & O’GormanMacher, P. A. More extreme precipitation in the world’s dry and wet regions. Nat. Climate Change 6, 508–514 (2016).

Kirschbaum, M. U. Will changes in soil organic carbon act as a positive or negative feedback on global warming?. Biogeochemistry 48, 21–51 (2000).

Ma, M. et al. Soil respiration of four forests along elevation gradient in northern subtropical China. Ecol. Evol. 9(22), 12846–12857 (2019).

Zhou, T., Shi, P., Hui, D., & Luo, Y. Global pattern of temperature sensitivity of soil heterotrophic respiration (Q10) and its implications for carbon‐climate feedback. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 114(G2) (2009).

Li, J., Pei, J., Pendall, E., Fang, C. & Nie, M. Spatial heterogeneity of temperature sensitivity of soil respiration: A global analysis of field observations. Soil Biol. Biochem. 141, 107675 (2020).

Högberg, P. et al. Large-scale forest girdling shows that current photosynthesis drives soil respiration. Nature 411(6839), 789–792 (2001).

Warembourg, F. R. & Estelrich, H. D. Plant phenology and soil fertility effects on below-ground carbon allocation for an annual (Bromus madritensis) and a perennial (Bromus erectus) grass species. Soil Biol. Biochem. 33(10), 1291–1303 (2001).

Cahoon, S. M. et al. Limited variation in proportional contributions of auto-and heterotrophic soil respiration, despite large differences in vegetation structure and function in the Low Arctic. Biogeochemistry 127, 339–351 (2016).

Rey, A. N. A. et al. Annual variation in soil respiration and its components in a coppice oak forest in Central Italy. Glob. Change Biol. 8(9), 851–866 (2002).

Riveros-Iregui, D. A. et al. Diurnal hysteresis between soil CO2 and soil temperature is controlled by soil water content. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL030938 (2007).

Yu, J. C., Chiang, P. N., Lai, Y. J., Tsai, M. J. & Wang, Y. N. High rainfall inhibited soil respiration in an Asian monsoon forest in Taiwan. Forests 12(2), 239 (2021).

Curiel Yuste, J. et al. Microbial soil respiration and its dependency on carbon inputs, soil temperature and moisture. Glob. Change Biol. 13(9), 2018–2035 (2007).

Linn, D. M. & Doran, J. W. Effect of water-filled pore space on carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide production in tilled and nontilled soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 48(6), 1267–1272 (1984).

Singh, S., Mayes, M. A., Kivlin, S. N. & Jagadamma, S. How the Birch effect differs in mechanisms and magnitudes due to soil texture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 179, 108973 (2023).

Chae, N. Annual variation of soil respiration and precipitation in a temperate forest (Quercus serrata and Carpinus laxiflora) under East Asian monsoon climate. J. Plant Biol. 54, 101–111 (2011).

Kwon, H., Kim, J., & Hong, J. Influence of the Asian Monsoon on net ecosystem carbon exchange in two major plant functional types in Korea. Biogeosciences Discussions, 6(6) (2009).

Birch, H. F. The effect of soil drying on humus decomposition and nitrogen availability. Plant Soil 10, 9–31 (1958).

Chen, S., Lin, G., Huang, J. & Jenerette, G. D. Dependence of carbon sequestration on the differential responses of ecosystem photosynthesis and respiration to rain pulses in a semiarid steppe. Glob. Change Biol. 15(10), 2450–2461 (2009).

Metz, E. M. et al. Soil respiration–driven CO2 pulses dominate Australia’s flux variability. Science 379(6639), 1332–1335 (2023).

Joshi-Saha, A. & Reddy, K. S. The pulse of pulses under climate change: From physiology to phenology. In Climate Change and Crop Production 143–162 (CRC Press, 2018).

Díaz-Pinés, E. et al. Root trenching: a useful tool to estimate autotrophic soil respiration? A case study in an Austrian mountain forest. Eur. J. Forest Res. 129(1), 101–109 (2010).

Epron, D. (2009). 8 r Separating autotrophic and heterotrophic components of soil respiration: lessons learned from trenching and related root-exclusion experiments.

Subke, J. A., Inglima, I. & Cotrufo, M. F. Trends and methodological impacts in soil CO2 efflux partitioning: A meta analytical review. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 921–943 (2006).

Song, H., Yan, T., Wang, J. & Sun, Z. Precipitation variability drives the reduction of total soil respiration and heterotrophic respiration in response to nitrogen addition in a temperate forest plantation. Biol. Fertil. Soils 56, 273–279 (2020).

Christensen, B. T., Lærke, P. E., Jørgensen, U., Kandel, T. P. & Thomsen, I. K. Storage of Miscanthus-derived carbon in rhizomes, roots, and soil. Can. J. Soil Sci. 96(4), 354–360 (2016).

Kuzyakov, Y. & Blagodatskaya, E. Microbial hotspots and hot moments in soil: concept & review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 83, 184–199 (2015).

Jian, J., R. Vargas, K.J. Anderson-Teixeira, E. Stell, V. Herrmann, M. Horn, N. Kholod, J. Manzon, R. Marchesi, D. Paredes, and B.P. Bond-Lamberty. A Global Database of Soil Respiration Data, Version 5.0. ORNL DAAC, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, USA. (2021). https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1827

Korea Meteorological Administration. (2024). KMA data portal. Korea Meteorological Administration. https://data.kma.go.kr/cmmn/main.do.

el Zahar Haichar, F., Santaella, C., Heulin, T. & Achouak, W. Root exudates mediated interactions belowground. Soil Biol. Biochem. 77, 69–80 (2014).

Beeckman, T. & Eshel, A. (eds) Plant roots: the hidden half (CRC Press, 2024).

Marschner, B. & Bredow, A. Temperature effects on release and ecologically relevant properties of dissolved organic carbon in sterilised and biologically active soil samples. Soil Biol. Biochem. 34(4), 459–466 (2002).

Wei, H. et al. Are variations in heterotrophic soil respiration related to changes in substrate availability and microbial biomass carbon in the subtropical forests?. Sci. Rep. 5(1), 18370 (2015).

Savage, K. E., Davidson, E. A., Abramoff, R. Z., Finzi, A. C. & Giasson, M. A. Partitioning soil respiration: quantifying the artifacts of the trenching method. Biogeochemistry 140, 53–63 (2018).

Sun, L., Ataka, M., Kominami, Y. & Yoshimura, K. Relationship between fine-root exudation and respiration of two Quercus species in a Japanese temperate forest. Tree Physiol. 37(8), 1011–1020 (2017).

Shen, X., Yang, F., Xiao, C. & Zhou, Y. Increased contribution of root exudates to soil carbon input during grassland degradation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 146, 107817 (2020).

Moinet, G. Y. et al. The temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter decomposition is constrained by microbial access to substrates. Soil Biol. Biochem. 116, 333–339 (2018).

Collalti, A. et al. Plant respiration: Controlled by photosynthesis or biomass?. Glob. Change Biol. 26(3), 1739–1753 (2020).

Arrhenius, S. Über die Reaktionsgeschwindigkeit bei der Inversion von Rohrzucker durch Säuren. Z. Phys. Chem. 4(1), 226–248 (1889).

Su, J. et al. Low carbon availability in paleosols nonlinearly attenuates temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter decomposition. Glob. Change Biol. 28(13), 4180–4193 (2022).

Davidson, E. A. & Janssens, I. A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440(7081), 165–173 (2006).

Tang, X. et al. Global patterns of soil autotrophic respiration and its relation to climate, soil and vegetation characteristics. Geoderma 369, 114339 (2020).

Yan, Y. et al. Heterotrophic respiration and its proportion to total soil respiration decrease with warming but increase with clipping. CATENA 215, 106321 (2022).

Zhao, Z. & Shi, F. Influence of temperature and moisture on autotrophic and heterotrophic respiration in a semi-arid highland elm sparse forest. Eurasian Soil Sci. 55(10), 1384–1394 (2022).

Manzoni, S., Schimel, J. P. & Porporato, A. Responses of soil microbial communities to water stress: results from a meta-analysis. Ecology 93(4), 930–938 (2012).

Briones, M. J. et al. Species selection determines carbon allocation and turnover in Miscanthus crops: Implications for biomass production and C sequestration. Sci. Total Environ. 887, 164003 (2023).

Min, K. et al. Active microbial biomass decreases, but microbial growth potential remains similar across soil depth profiles under deeply-vs. shallow-rooted plants. Soil Biol. Biochem. 162, 108401 (2021).

Anderson, J. P. & Domsch, K. H. A physiological method for the quantitative measurement of microbial biomass in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 10(3), 215–221 (1978).

Quan, Q. et al. Water scaling of ecosystem carbon cycle feedback to climate warming. Sci. Adv. 5(8), 1131 (2019).

R Core Team (2024). _R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. <https://www.R-project.org/>.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Technology Development Project for Creation and Management of Ecosystem based Carbon Sinks (RS-2023-00218237) through KEITI, Ministry of Environment, Korea, the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (RS-2024-00336378, RS-2024-00405420), and the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, and Forestry (RS-2024-00398300). We appreciate Prof. Do-Soon Kim and Dr. Jaehyoung You at Seoul National University for allowing us to collect soil samples and perform fieldwork at their long-term experimental field site. We are also grateful to Prof. Sharon Billings for insightful reviews and to Hyungju Kim for the help with the fieldwork.

Funding

Ministry of Environment, RS-2023-00218237, National Research Foundation of Korea, RS-2024-00336378, National Research Foundation, RS-2024-00405420, Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, and Forestry, RS-2024-00398300.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HK and KM designed the experiment. HK, SK, and SW performed the experiment and analyzed data. HK wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and gave final approval for the submission of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Kim, S., Woo, S. et al. Soil heterotrophic and autotrophic respiration respond differently to seasonal variations in temperature and water content under monsoon continental climate. Sci Rep 15, 20554 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06082-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06082-x