Abstract

After highly invasive cardiac surgery, critically ill patients require night-time nursing care for life support. Even in patients administered dexmedetomidine for sedation, nursing care potentially disrupts sleep and affects circadian rhythms. However, the impact of night-time nursing care on sleep in intensive care unit (ICU) patients have not been objectively evaluated, and the effects of sedatives have not been objectively confirmed. The current study investigated how night-time nursing care affected sleep in patients who had undergone cardiac surgery, by analyzing dynamic changes in electroencephalogram (EEG) data. Two groups were investigated: a dexmedetomidine group and a non-dexmedetomidine group. The decision whether to administer dexmedetomidine was based on clinical judgment. EEG data were extracted for 30 s intervals before and after performing care for 150 s. Power spectrum density (PSD) was analysed using a linear mixed-effects model. In both groups, PSD (alpha and beta bands) was significantly higher after care than before care. Intermittent sleep occurred during nursing care even in patients under dexmedetomidine sedation. Thus, regardless of whether sedatives are used nighttime nursing care causes sleep interruptions, and centralizing nursing and routine care is crucial to ensure good sleep.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep comprises a 90–120-min cycle of transition from non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is repeated 3–5 times. The role of sleep includes recovery from fatigue and stress, energy preservation, neurological pathway constitution, and functional adjustment of body temperature. Sleep disruption reduce to immunity1 and increases glucose intolerance, and sympathetic hyperactivity2. Therefore, sleep plays an important role in life support. Critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) typically undergo invasive treatments, such as surgery, which elevate the levels of inflammatory cytokines that control biological defense reactions, such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and tumour necrosis factor3. These inflammatory cytokines exhibit sleep-inducing behaviors and induce NREM sleep4. The level of cytokines correlates with the invasiveness of treatment, and patients who undergo highly invasive procedures, such as cardiac surgery, exhibit increased cytokine levels5. Therefore, ensuring that critically ill patients receive quality sleep is crucial for their recovery. In 2018, the Society of Critical Care Medicine published clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult ICU patients (the PADIS guidelines), which emphasize the importance of promoting sleep care6.

However, several critically ill patients who require intensive care experience sleep disruption, which is characterized by sleep fragmentation, increased light sleep, and decreased slow-wave sleep7,8. Mechanically ventilated patients experience reduced total sleep time, abnormal sleep architecture, and increased sleep fragmentation owing to sleep interruption caused by asynchronization with mechanical ventilation and spontaneous respiration9. Adjunctive sedative agents, such as propofol and benzodiazepines, reduce the time spent in REM and slow-wave sleep (SWS) by modulating the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor10,11. In non-intubated critically ill patients, sleep quality is reduced by discomfort, pain, and anxiety12,13. Sleep can be disrupted by environmental factors, such as noise and light in the ICU14,15. Additionally, many critically ill patients, especially those who undergo cardiac surgery, require intensive management including nursing care, such as the measurement of vital signs, blood sampling, and position changes at night to support life and enable timely detection of abnormalities16. However, medical professionals mostly determine the time of care without considering the patients’ sleep conditions.

Dexmedetomidine, an α2-adrenergic receptor agonist, is frequently used for sedation in critically ill, non-intubated patients17. The dexmedetomidine-induced sleep-like state increases stage N2 sleep and sleep efficiency, decreases stage N1 sleep, and prolongs total sleep time18,19. However, in patients who received dexmedetomidine, the wake time after sleep onset was longer than that in patients who received other sedatives, such as propofol20. Thus, although dexmedetomidine offers some benefits for sleep promotion, its sedative effects may still be disrupted by night-time nursing care. Previous studies of the relationship between nursing care and sleep have primarily relied on subjective questionnaires21,22,23, which lack objective physiological data. Though previous studies using electroencephalography (EEG) have evaluated sleep quality, including sleep stages and total sleep time, the impact of night-time nursing care on the sleep of patients in the ICU remains unclear.

This study aimed to investigate how night-time nursing care affects sleep in patients who have undergone cardiac surgery based on an analysis of dynamic EEG changes. Accordingly, we explored two groups: patients experiencing a sleep-like state-induced by dexmedetomidine administration and naturally sleeping patients without dexmedetomidine.

Methods

Study design and setting

This is prospective, observational study. This study was conducted in an 8-bed ICU at Shizuoka Municipal Hospital, Japan. The ICU is an open-space room with beds separated by curtains. Nursing staff usually measure vital signs to assess the patients’ condition every 2h and perform other nursing care simultaneously as much as possible. At night, the lighting in the ICU is typically dimmed to a level that allows nursing staff to provide care. Additionally, nursing staff provide to minimize noise and avoid bright lighting as much as possible to prevent sleep disruptions.

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Osaka University Hospital (21217-3) and the Ethics Review Committee of Shizuoka Municipal Hospital (21–89). All patients were given oral explanations and provided written informed consent in advance regarding the purpose, method, safety considerations, and risks of the experiment when they visited the ICU because of their preoperative orientation. This study was conducted in accordance with relevant named guidelines and regulations.

Patient recruitment

This study enrolled ICU-admitted patients who underwent elective cardiac surgery under general anesthesia between April 1, 2022, and June 31, 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients aged ≥ 20 years; (2) patients who underwent open chest surgery, such as cardiac or aortic surgery; (3) patients who had the tracheal tube removed in the ICU after surgery; and (4) patients who understood Japanese and could provide informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) unscheduled ICU admission; (2) hemodynamically unstable state with Forrester classification IV; (3) history of cerebrovascular disease, dementia, sleep disorder, psychiatric disorder, or abuse of alcohol and drug abuse; (4) occurrence of delirium after ICU admission; and (5) use of adaptive servo-ventilation and drugs for sleep disorders before cardiac surgery. First, in the preoperative phase, we collected data on patient characteristics and surgical information and selected patients who met the inclusion criteria (1–4) and did not meet the exclusion criteria (1, 3 and 5). Subsequently, the patients who underwent surgery and were extubated in the ICU were included as study participants if they did not meet the exclusion criteria (2) and (4).

Patients received dexmedetomidine based on their condition, such as difficulty in sleeping, according to the physician’s instruction in usual practice. The assignment of whether to receive dexmedetomidine was not made as part of the research but rather followed clinical judgment. Accordingly, the dexmedetomidine and non-dexmedetomidine groups were formed based on these natural classifications. The dexmedetomidine group included patients who were administered the drug between 21:00 and 06:00. As an institutional protocol, the dose of dexmedetomidine is adjusted to achieve a Richmond agitation sedation scale of -1 or -2. In cases of hemodynamic instability (decreased blood pressure and heart rate), the dose of dexmedetomidine was reduced. Patients did not receive propofol, which induces respiratory inhibition, because this study focused on patients whose tracheal tubes have been removed, as well as benzodiazepines, which may cause delirium. Moreover, nursing staff evaluated the pain level using a visual analogue scale, and patients were administered intramuscular pentazocine as needed when they experienced pain.

Measurement methods

The patients’ sleep data were recorded using ZA-X (Proassist Co., Osaka, Japan), a portable recording system that can measure EEG from Fp1, electrooculogram (EOG), and electromyogram (EMG) data by attaching electrodes to the skin of the superior and opposite inferior eyelids, chin muscles, and mastoid areas. Patients were immediately removed from EEG monitoring and excluded from the study if they complained of discomfort or developed skin trouble from the electrodes. This device records a sampling frequency of 128 Hz and is composed of a receiver (dimensions: 76 mm × 135 mm) and a transmitter (dimensions: 36 mm × 65 mm). The concordance of this device with polysomnography (PSG) has been reported to be 85.5%24, and it is used in the sleep science and medical fields.

Data collection

EEG data were collected between 21:00 and 07:00 on the day the tracheal tube was removed because patients who underwent cardiac surgery were generally discharged from the ICU the day after tracheal tube removal. This timeframe coincides with the secretion of melatonin, which regulates the sleep–wake cycle, starting at approximately 21:00 and returning to baseline by 07:00 in the pineal gland25,26.

Clinicodemographic data were collected from patients’ electronic medical records. The demographic data included age, sex, body mass index, and procedures. Clinical data included the duration of surgery, in/out balance during surgery, dexmedetomidine dose, vasopressors, and pentazocine. Regarding the nursing care provided, the nursing staff recorded variables and times by reading programmed QR code between 21:00 and 07:00. Care frequently performed in the ICU, either day or night, was set as the collecting data. Data on the nursing care performed included vital signs, neurological assessment, line/tube check, mechanical instrument check such as S-G catheter, infusion pump and syringe pomp, and flotrac system monitor™, X-ray, hygiene care, medication, oral administration, clothing changes, blood drawing via A-line, position changes in bed, respiration care, catheter removal, and communication with medical staff. Furthermore, we classified the procedures performed into two groups: care that involved touching the patients, such as vital signs and neurological assessment, and care that did not involve touching the patients, such as blood sampling, line/tube checks, and mechanical instrument checks. Care was calculated as the number of interventions per patient, mean time between interventions, and time and type of interventions performed. Interventions performed within a 5-min interval were considered one intervention27.

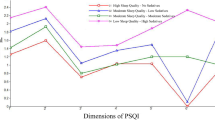

Data analysis

Data from simple EEG were obtained using a bandpass filter ranging from 0.5 to 40.0 Hz to remove the noise signals. These data were extracted 30 s before performing the interventions, and immediately after performing the interventions 150 s after performing care. Furthermore, the extracted data were divided into groups at 30-s intervals, and data obtained 30 s before performing care were considered the baseline, whereas those obtained after performing care were classified as A1–A5 (Fig. 1). If the obtained data were difficult to analyze owing an unstable wave caused by noise such as body motion, the data were excluded from the analysis. Nursing care that does not involve touching the patient was also included in this study because the noise caused by standing at the patient’s bedside can affect sleep. Many patients in the ICU show little or no changes in EEG patterns throughout the sleep cycle28, and evaluating sleep quality using EEG makes it difficult to clarify the impact of night-time care on sleep. Therefore, a frequency analysis was conducted using autoregressive modelling to calculate the power spectrum density (PSD), which was the primary outcome29. The PSD was then divided into the following specific frequency bands: δ (0.5–4.0 Hz); θ (4.0–8.0 Hz); α (8.0–13.0 Hz); and β (13.0–30.0 Hz)30. The delta band, which has a low frequency, represents the SWS appearing during deep sleep. The theta band increases in light sleep (N1 and N2) compared to that in the wake stage and decreases with deeper sleep; this frequency band cannot be observed in the wake stage. The alpha band is high in the relaxed eyes-closed awake state, N1, and REM sleep and gradually weakens as sleep deepens. Furthermore, the beta band increases during the wake stage and decreases during deep sleep, such as in N331,32. The calculated power spectra for specific frequency bands were normalized owing to the large individual differences in the PSDs. Furthermore, a wavelet transform was performed to observe temporal changes in the data over time. EEG analysis was performed using MATLAB 9.5 (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated based on the normalized alpha PSD, assuming a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. We determined the effect size as 0.45 and performed a two-sided t-test with a type I error rate (α) of 5% and a statistical power (β) of 80%. The required sample size was estimated to be 109 nursing care interventions per group. To account for potential dropouts, we decided to enroll 250 nursing care. Given the assumption that each patient would receive an average of ten nursing care services, including clustered care, and considering a 35% dropout rate, the estimated number of patients required was 75. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations or as numbers of individuals (percentages). Demographic and clinical data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data to compare the dexmedetomidine and non-dexmedetomidine groups. Furthermore, for statistical analysis of the PSD, we used a linear mixed-effects model (LMEM) with the normalized PSD as the objective variable for each frequency band, and the coefficient and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were estimated. Sex, age, time, and use of dexmedetomidine were included as fixed effects. Furthermore, the interaction terms included the observation point 30 s before and immediately after performing care for 150 s, which was divided into 30-s intervals, and whether dexmedetomidine was used. In the subgroup analysis, we performed LMEM in four groups that assigned touch or non-touch patient care and dexmedetomidine or non-dexmedetomidine groups, which were defined as dex (−)/touch (−), dex (−)/touch (+), dex (+)/touch (−), and dex (+)/touch (+). The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 18.1 (Stata Corp LLC, Texas, USA).

Results

Of the 76 patients screened for eligibility, 43 were included in this study, whereas 33 were excluded for the following reasons: (1) accurate EEG data were not obtained due to technical issues, (2) delirium, and (3) patient refusal (Fig. 2). Table 1 shows the participants’ characteristics: The mean age in this cohort was 68.26 ± 12.65 years, there were 27 (67.44%) male participants, and the mean duration of surgery was 270.93 ± 78.43 min. The patients underwent EEG measurements on the night of the postoperative day or the night of the following day; the mean extubating time was 637.14 ± 810.17 min after cardiac surgery. Twenty-four patients were administered dexmedetomidine overnight.

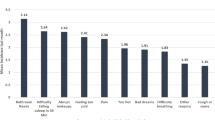

Nursing staffs recorded a total of 560 nursing care events for 43 patients, and the number of interventions was 13.02 ± 0.93 per patient during the night. The number of care clusters within a 5-min period was 217, and the mean time between interventions was 55.1 min. The number of interventions analyzed after the excluding interventions in which noise was obvious or the start or end time from the EEG was unidentifiable was 270, of which 147 and 123 were in the dexmedetomidine and non-dexmedetomidine groups, respectively. Several interventions were administered at 11 p.m. (n = 19, 15.2%), followed by those administered at 5 a.m. (n = 16, 13.0%) and 2 a.m. (n = 14, 11.2%) in patients who did not receive dexmedetomidine. In contrast, among those who received dexmedetomidine, a high percentage of interventions were performed at 10 p.m. (n = 20, 13.7%), followed by 11 p.m. (n = 20, 13.7%) and 5 a.m. (n = 17, 11.5%) (Fig. 3a). Figure 3b shows the percentage of nursing care provided.

Figure 4 presents the EEG activity in the non-dexmedetomidine (Fig. 4a) and dexmedetomidine (Fig. 4b) groups 30 s before nursing care (baseline; Fig. 4e and g) and immediately after, until 150 s following nursing care (A5; Fig. 4f and h). Wavelet analysis revealed that the delta waveband exhibited an increased PSD at baseline in both groups. In the dexmedetomidine group, the alpha wave band increased after nursing care was provided, whereas, in the non-dexmedetomidine group, both the delta and alpha bands exhibited a high density (Fig. 4c and d).

Example of EEG data and wavelet transform analysis. (a) EEG data obtained from the non-dexmedetomidine group; (b). EEG data obtained from the dexmedetomidine group; (c) and (d). scalograms of the wavelet transform by analyzing (a) and (b); (e) and (g). the expanded traces for periods before nursing care indicated by the downward arrow; (f) and (h) the expanded traces for periods immediately after nursing care indicated by the downward arrow.

Tables 2 and 3 present the coefficients and 95% CIs for the fixed effects and interaction terms, respectively, at specific EEG frequencies. Delta waves in the dexmedetomidine group did not differ significantly from those in the non-dexmedetomidine group. Regarding the interaction term, in the dexmedetomidine and non-dexmedetomidine groups, the delta wave at baseline did not significantly differ from that at A1–A5. The theta band intensity at A1 was significantly higher than that at baseline in the dexmedetomidine group (coefficient, 0.249; 95% CI, 0.058–0.440; p = 0.011). In the non-dexmedetomidine group, the theta band from A1 to A4 did not significantly differ from baseline. Regarding the alpha band, statistically significant differences were observed between baseline and A1 in the dexmedetomidine group (coefficient, 0.367; 95% CI, 0.138–0.596; p = 0.002) and between baseline and A1–A3 in the non-dexmedetomidine group (coefficient = 0.592, 95% CI = 0.400–0.780, p < 0.001; coefficient = 0.372, 95% CI = 0.193–0.552, p < 0.001; coefficient = 0.190, 95% CI = 0.011–0.370, p = 0.037). A significant difference in the beta band intensity was observed between baseline and A1 in the dexmedetomidine group (coefficient, 0.271; 95% CI, 0.040–0.502; p < 0.021). Furthermore, a significant difference in the beta band was observed between the baseline and A1 and A2 in the non-dexmedetomidine group (coefficient = 0.382, 95% CI = 0.192–0.572, p < 0.001; coefficient = 0.181, 95% CI = 0.001–0.362, p = 0.049). Subgroup analysis showed that the number of nursing care instances was 50 in the dex (−)/touching (−) group, 37 in the dex (−)/touching (+) group, 73 in the dex (+)/touching (−) group, and 110 in the dex (+)/touching (+) group. The delta band was not significantly different between the baseline and A1–A5 in any group. In contrast, the theta band significantly differed from the baseline in both the dex (−)/touching (−) and dex (+)/touching (+) groups. The alpha band was significantly increased from the baseline in the dex (−)/touching (+) and dex (+)/touching (+) groups. Additionally, the beta band was significantly increased from the baseline in the dex (−)/touching (+), dex (+)/touching (−), and dex (+)/touching (+) groups (Supplemental Table S1 online).

Discussion

This study investigated how night-time nursing care affects sleep in patients who underwent cardiac surgery by quantitatively analyzing the dynamic changes in EEG. To explore this, we investigated two groups: patients who experienced a sleep-like state induced by dexmedetomidine administration and those who slept naturally without dexmedetomidine sedation. An average of 13.02 nursing care events per patient were performed each night, with a mean 55.02 min interval between interventions. According to the LMEM results, the PSDs of alpha and beta bands were significantly higher after nursing care than before nursing care in both the dexmedetomidine and non-dexmedetomidine group. It was suggested that the patients admitted to the ICU who underwent cardiac surgery, even with dexmedetomidine sedation, experienced disrupted sleep owing to night-time nursing care, and caused arousal or shallow sleep.

Dexmedetomidine is an elective α2-adrenergic receptor agonist that activates GABAergic neurons in the ventral lateral preoptic area (VLPO) by combining with α2 receptors and inhibiting the release of noradrenaline from the locus coeruleus (LC)33,34. Similar to natural sleep, the activation of GABAergic neurons inhibits the release of neurotransmitters such as orexin, histamine, and acetylcholine from the brainstem and hypothalamus35. The EEG characteristics resemble those of N2 sleep, which has delta and spindle oscillations36,37. Noradrenergic neurons located in the LC project to the lateral hypothalamus, VLPO, and cerebral cortex38 and, thereby, promote and maintain the awake state by activating orexinergic neurons, further inhibiting GABAergic neurons and releasing them into the cerebral cortex. LC neurons are activated by all sensory stimuli, including visual, auditory, and somatosensory stimuli39, and increase the release of noradrenaline40. Consequently, sedation induced by dexmedetomidine is more arousing than that induced by other sedatives, such as propofol41. In patients who received dexmedetomidine, the wake time after sleep onset was longer than that in patients who received propofol20. Critically ill patients admitted to the ICU experience a sleep architecture that is characterized by a reduction in SWS and REM sleep and an increase in light sleep, such as N1 and N2 sleep42. The thermal stimulus threshold causing arousal during N2 sleep is lower than that during SWS43, and the somatosensory responsiveness peaks during light sleep44. In this study, alpha- and beta-band PSDs were higher after nursing care than before, which indicated that the acoustic and somatosensory stimulation caused by nursing care in ICU patients during light sleep may have activated noradrenergic neurons and various wake–sleep mechanisms that resulted in arousal. These results suggest that patients receiving dexmedetomidine can be easily aroused by nursing care. This study identified crucial knowledge regarding nursing care for patients under sedation.

The sleep architecture comprises a 90–120-min cycle, which includes NREM and REM sleep. NREM sleep is divided into N1, N2, and N3 stages, collectively known as SWS30. Although sleep gradually deepens over time and reaches the N3 sleep stage after approximately 30 min, the sleep stage remains depthless due to sleep disruption and microarousal caused by repeated nursing care. Therefore, the interval between nursing care sessions must be at least 90 min to maintain sleep in ICU patients27. However, critically ill patients, particularly those who have undergone cardiovascular surgery, require several interventions to administer whole-body management and detect abnormalities early. Furthermore, the more severe the patient’s condition, the higher the frequency of nursing care45. Tamburri et al. reported that only 6% of patients had periods of sleep between interventions ≥ 2 h16. In this study, 560 nursing care procedure were performed at night for 43 patients (13.02 nursing care per patient), and the mean time between nursing care was 55.02 min. The most common types of nursing care were vital sign assessments, blood sampling, and line-and-tube checks. The increase in night-time nursing care shortens the intervals between nursing care session and frequently induces arousal, which may adversely affect the sleep cycle and quality. Inadequate sleep is a risk factor in postoperative delirium. Accordingly, centralizing nursing care by scheduling care plans that consider routine care is important to ensure adequate sleep in ICU patients. This study demonstrated the relationship between night-time nursing care and sleep in patients in the ICU by quantitatively evaluating physiological data, such as EEG, instead of a previous subjective evaluation. These findings are crucial for enhancing sleep care in ICU patients in clinical settings.

Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. The data collection period exceeded 2 years. Nurses are responsible for caring for all patients in the ICU, and not just the study participants. Therefore, we needed to ensure that the study did not negatively impact other patients. Under circumstances where patient safety could not be guaranteed, data collection was not possible. This was one of the reasons for the prolonged study period. This study was conducted at a single institution, which may be confer bias regarding the participant selection, surgery, and nursing care. Multicenter studies of patients admitted to the ICU are required to overcome these limitations. We analyzed data recorded in only 30 s before performing interventions and up to 150 s immediately after care; however, we did not evaluate sleep quality, such as sleep stage, because the research focus was on the impact of night-time nursing care that causes light sleep and arousal. Therefore, the relationship between night-time nursing care and sleep quality should be explored in future studies. Furthermore, in this study, a single-channel EEG device, rather than PSG, was used to measure the sleep of patients in the ICU. This device could only record a single EEG channel from the frontal cortex, although the presence of electrodes did not interfere with sleep. However, measuring sleep using more EEG channels is necessary because changes in the alpha band are observed in the occipital lobe. The sample size was very small because accurate EEG data could not be obtained owing to technical issues. Consequently, although this study investigated the types and timing of nursing care, we were unable to discuss the effects of individual nursing care on EEG. The relationship between type of nursing care and sleep needs to be explored in future studies. Finally, subjective questionnaires were not used because we focused on biomedical signals to objectively assess sleep. Therefore, both subjective and objective sleep assessments should be considered.

In conclusion, this study revealed the effects of nursing care provided at night on the sleep of non-intubated patients in the ICU through dynamic EEG changes. Alpha- and beta-band PSDs increased after nursing care compared to those before nursing care in the non-dexmedetomidine and dexmedetomidine groups. These findings suggest that ICU patients experience interrupted sleep during night-time nursing care. The most common types of care activities included vital sign assessments, blood sampling, and line-and-tube checks. Furthermore, the average sleep duration between nursing care sessions was shorter than 90 min of the sleep cycle, consisting of NREM to REM sleep. Accordingly, centralizing nursing care by scheduling care plans that consider the need for routine care, even when patients in the ICU are sedated with dexmedetomidine, is important to ensure adequate sleep.

Data availability

The data are not publicly available due to restrictions, such as containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. However, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalography

- EMG:

-

Electromyography

- EOG:

-

Electrooculography

- GABA:

-

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- LC:

-

Locus coeruleus

- LMEM:

-

Linear mixed-effect model

- NREM:

-

Nonrapid eye movement

- PSD:

-

Power spectrum density

- PSG:

-

Polysomnography

- REM:

-

Rapid eye movement

- SWS:

-

Slow-wave sleep

- VLPO:

-

Ventral lateral preoptic area

References

Ganz, F. D. Sleep and immune function. Crit. Care Nurse 32, e19-25 (2012).

Spiegel, K., Leproult, R. & Van Cauter, E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet 354, 1435–1439 (1999).

Ingiosi, A. M., Opp, M. R. & Krueger, J. M. Sleep and immune function: glial contributions and consequences of aging. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 23, 806–811 (2013).

Jewett, K. A. & Krueger, J. M. Humoral sleep regulation; interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor. Vitam. Horm. 89, 241–257 (2012).

Kuswardhani, R. A. T. & Sugi, Y. S. Factors related to the severity of delirium in the elderly patients with infection. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 3, 2333721417739188 (2017).

Devlin, J. W. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 46, e825–e873 (2018).

Shaikh, H. et al. Effect of atypical sleep EEG patterns on weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest 165, 1111–1119 (2024).

Eskioglou, E. et al. Electroencephalography of mechanically ventilated patients at high risk of delirium. Acta Neurol. Scand. 144, 296–302 (2021).

Rittayamai, N. et al. Positive and negative effects of mechanical ventilation on sleep in the ICU: A review with clinical recommendations. Intensive Care Med. 42, 531–541 (2016).

Moody, O. A. et al. The neural circuits underlying general anesthesia and sleep. Anesth. Analg. 132, 1254–1264 (2021).

Silverstein, B. H. et al. Effect of prolonged sedation with dexmedetomidine, midazolam, propofol, and sevoflurane on sleep homeostasis in rats. Br. J. Anaesth. 132, 1248–1259 (2024).

Stewart, J. A., Green, C., Stewart, J. & Tiruvoipati, R. Factors influencing quality of sleep among non-mechanically ventilated patients in the Intensive Care Unit. Aust. Crit. Care 30, 85–90 (2017).

Jodaki, K. et al. Effect of rosa damascene aromatherapy on anxiety and sleep quality in cardiac patients: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther. Clin. Pract. 42, 101299 (2021).

Navarro-Garcia, M. A. et al. Quality of sleep in patients undergoing cardiac surgery during the postoperative period in intensive care. Enferm. Intensiva 28, 114–124 (2017).

Mermer, E. & Arslan, S. The effect of audiobooks on sleep quality and vital signs in intensive care patients. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 80, 103552 (2024).

Casida, J. M., Davis, J. E., Zalewski, A. & Yang, J. J. Night-time care routine interaction and sleep disruption in adult cardiac surgery. J. Clin. Nurs. 27, e1377–e1384 (2018).

Yang, B., Gao, L. & Tong, Z. Sedation and analgesia strategies for non-invasive mechanical ventilation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung 63, 42–50 (2024).

Romagnoli, S. et al. Sleep duration and architecture in non-intubated intensive care unit patients: an observational study. Sleep Med. 70, 79–87 (2020).

Wu, X. H. et al. Low-dose dexmedetomidine improves sleep quality pattern in elderly patients after noncardiac surgery in the intensive care unit: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology 125, 979–991 (2016).

Guldenmund, P. et al. Brain functional connectivity differentiates dexmedetomidine from propofol and natural sleep. Br. J. Anaesth. 119, 674–684 (2017).

Bihari, S. et al. Factors affecting sleep quality of patients in intensive care unit. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 8, 301–307 (2012).

Cicek, H. et al. Sleep quality of patients hospitalized in the coronary intensive care unit and the affecting factors. Int. J. Caring Sci. 7, 324–332 (2014).

Ahn, Y. H., Lee, H. Y., Lee, S. M. & Lee, J. Factors influencing sleep quality in the intensive care unit: A descriptive pilot study in Korea. Acute Crit. Care 38, 278–285 (2023).

Nonoue, S. et al. Inter-scorer reliability of sleep assessment using EEG and EOG recording system in comparison to polysomnography. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 15, 39–48 (2017).

Brzezinski, A. Melatonin in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 186–195 (1997).

Pevet, P. & Challet, E. Melatonin: Both master clock output and internal time-giver in the circadian clocks network. J. Physiol. Paris 105, 170–182 (2011).

Ritmala-Castren, M., Virtanen, I., Leivo, S., Kaukonen, K. M. & Leino-Kilpi, H. Sleep and nursing care activities in an intensive care unit. Nurs. Health Sci. 17, 354–361 (2015).

Wilcox, M. E. et al. Sleep on the ward in intensive care unit survivors: a case series of polysomnography. Intern. Med. J. 48, 795–802 (2018).

Beck, J., Loretz, E. & Rasch, B. Stress dynamically reduces sleep depth: temporal proximity to the stressor is crucial. Cereb. Cortex 33, 96–113 (2022).

Berry, R. B. et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 8, 597–619 (2012).

Lombardi, F. et al. Beyond pulsed inhibition: Alpha oscillations modulate attenuation and amplification of neural activity in the awake resting state. Cell Rep. 42, 113162 (2023).

Hussain, I. et al. Quantitative evaluation of EEG-biomarkers for prediction of sleep stages. Sensors (Basel) 22, 3079 (2022).

Yu, X., Franks, N. P. & Wisden, W. Sleep and sedative states induced by targeting the histamine and noradrenergic systems. Front. Neural Circ. 12, 4 (2018).

Fan, S. et al. The α(2) adrenoceptor agonist and sedative/anaesthetic dexmedetomidine excites diverse neuronal types in the ventrolateral preoptic area of male mice. ASN Neuro 15, 17590914231191016 (2023).

Brown, E. N., Lydic, R. & Schiff, N. D. General anesthesia, sleep, and coma. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 2638–2650 (2010).

Akeju, O. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of dexmedetomidine-induced electroencephalogram oscillations. PLoS ONE 11, e0163431 (2016).

Huupponen, E. et al. Electroencephalogram spindle activity during dexmedetomidine sedation and physiological sleep. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 52, 289–294 (2008).

Schwarz, L. A. et al. Viral-genetic tracing of the input-output organization of a central noradrenaline circuit. Nature 524, 88–92 (2015).

Ge, D., Han, C., Liu, C. & Meng, Z. Neural oscillations in the somatosensory and motor cortex distinguish dexmedetomidine-induced anesthesia and sleep in rats. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 31, e70262 (2025).

Suzuki, T., Nagasaka, K., Otsuki, T., Otsuru, N. & Onishi, H. Tonic electrical stimulation of the locus coeruleus enhances cortical sensory-evoked responses via noradrenaline α1 and β receptors. Eur. J. Neurosci. 61, e70020 (2025).

Ter Bruggen, F., Ceuppens, C., Leliveld, L., Stronks, D. L. & Huygen, F. Dexmedetomidine vs propofol as sedation for implantation of neurostimulators: A single-center single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 63, 1321–1329 (2019).

Vacas, S. et al. The feasibility and utility of continuous sleep monitoring in critically Ill patients using a portable electroencephalography monitor. Anesth. Analg. 123, 206–212 (2016).

Bentley, A. J., Newton, S. & Zio, C. D. Sensitivity of sleep stages to painful thermal stimuli. J. Sleep Res. 12, 143–147 (2003).

Leung, C. G. & Mason, P. Physiological properties of raphe magnus neurons during sleep and waking. J. Neurophysiol. 81, 584–595 (1999).

Giusti, G. D., Tuteri, D. & Giontella, M. Nursing interactions with intensive care unit patients affected by sleep deprivation: An observational study. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 35, 154–159 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank the nursing staff in the ICU of Shizuoka Municipality Hospital for support of the study. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP22K10813.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YM, YO, and TU conceived and designed the study, and performed the analysis and interpretation. HN, MN, RA, and AI acquired the data. YM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsuura, Y., Ohno, Y., Natori, H. et al. Electroencephalography-based evaluation of the impact of night-time nursing care on sleep during intensive care unit administration after cardiac surgery. Sci Rep 15, 22913 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06088-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06088-5