Abstract

The zero-inflated negative binomial regression (ZINBR) model is used for modeling count data that exhibit both overdispersion and zero-inflated counts. However, a persistent challenge in the efficient estimation of parameters within ZINBR models is the issue of multicollinearity, where high correlations between predictor variables can compromise the stability and reliability of the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE). We propose a new two-parameter hybrid estimator, designed for the ZINBR model, to address this problem. This estimator aims to mitigate the effects of multicollinearity by incorporating a combination of existing biased estimators. To test the effectiveness of the proposed estimator, we conduct a comprehensive theoretical comparison with conventional biased estimators, including the Ridge and Liu, the Kibria-Lukman, and the modified Ridge estimators. An extended Monte Carlo simulation study complements the theoretical results, evaluating the estimator’s performance under various multicollinearity conditions. The simulation results, evaluated by metrics such as mean squared error (MSE) and mean absolute error (MAE), show that the proposed hybrid estimator consistently outperforms conventional methods, especially in high multicollinearity. Furthermore, we apply it to two real-world datasets. The experimental application demonstrates the superior performance of the estimator in producing stable and accurate parameter estimates. The simulation study and experimental application results strongly suggest that the new two-parameter hybrid estimator offers significant progress in parameter estimation in ZINBR models, especially in complex scenarios due to multicollinearity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Poisson and negative binomial regression models are commonly employed in analyzing count data to elucidate the relationship between the response variable and explanatory variables. The Poisson model, however, assumes that the variance of the count data equals the mean, which often proves inadequate for real-world scenarios where overdispersion is present-i.e. when the variance exceeds the mean. The negative binomial regression model extends the Poisson framework by allowing the variance to be a function of the mean, thereby providing greater flexibility in accommodating overdispersion1.

Count data often exhibit an excess of zeros that exceeds what would be predicted by either Poisson or negative binomial models. Such excess zeros are often significant, as they may indicate underlying processes or special status that simple count models fail to address. The ZINBR model is utilized to capture these characteristics. Greene2 introduced the ZINBR model, which integrates a negative binomial distribution with a zero-inflation component, providing a comprehensive approach to address overdispersion and the prevalence of excess zeros in the data. The ZINBR model excels in providing an advanced understanding of count data when traditional models are inadequate.

In econometric modeling, particularly for the ZINBR model where explanatory variables are often correlated3, multicollinearity is a frequent challenge. In instances of multicollinearity, the covariance matrix of the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) may exhibit instability, resulting in inflated variances and standard errors of the regression coefficients. This inflation may diminish the coefficient’s statistical significance, expand confidence intervals, and increase the likelihood of Type II errors. Traditional methods to address multicollinearity include acquiring more data, modifying the model definition, or removing strongly correlated variables. However, removing variables may lead to an under fitted model, resulting in the loss of critical information about the underlying relationships among the variables4,5.

Biased estimation methods are commonly employed to address the challenges of multicollinearity. Among these, the ridge regression estimator6,7 is one of the most effective techniques for mitigating the impact of correlated predictor variables. The selection of an optimal ridge parameter is critical for the performance of this method, with various studies offering insights into effective parameter selection, such as those by Kibria8, Khalaf and Shukur9, and Muniz and Kibria10, García García et al.11, Abonazel et al.12.

Despite its advantages, ridge regression is limited by its complex non-linear dependence on the ridge parameter. To overcome this limitation, Liu13 introduced a biased estimator combining ridge regression’s benefits and the Stein estimator. Furthermore, various other estimators have been introduced in the literature, including Özkale Kaciranlar estimator14, the Liu type estimator15, new probit regression model estimator16, Modified Liu estimator17, enlarging of the sample18, Dawoud et al.19, Modified ridge-type estimator20, new Tobit Ridge-type estimator21, Kibria Lukman estimator22, Dawoud Kibria estimator23, new hybrid estimator24, and others. For the ZINBR model, Al-Taweel and Algamal3 introduced an almost unbiased ridge estimator, Akram et al.25 defined Stein estimator, Zandi et al.26 described improved shrinkage estimators, Dawoud and Eledum27 developed stochastic restricted biased estimator, Akram et al.28 presented Kibria-Lukman estimator, Zandi ety al.29 introduced Liu-type estimator, and Akram et al.30 defined modified ridge-type estimator.

Recently, Shewa and Ugwuowo24 developed an innovative hybrid estimator to address multicollinearity in linear regression models (LRMs) by combining the modified ridge-type estimator with the Kibria-Lukman estimator. This novel approach incorporates two shrinkage parameters, \(k\) and \(d\), to effectively mitigate multicollinearity issues, harnessing the advantages of both estimators. Despite its potential, applications of this hybrid estimator in generalized linear models (GLMs) remain sparse, with only a single study reported in the literature. Notably, Alrweili31 examined the Kibria-Lukman hybrid estimator in the context of Poisson regression. This paper aims to extend this approach by introducing a new hybrid Kibria-Lukman estimator specifically for the zero-inflated negative binomial regression (ZINBR) model. The proposed method is designed to improve parameter estimation a midst correlated predictors. Comprehensive theoretical comparisons are conducted using both matrix mean squared error (MMSE) and scalar mean squared error (MSE) criteria. Additionally, the performance of the proposed estimator is assessed through a Monte Carlo simulation study under diverse parametric conditions. The paper concludes with an empirical application demonstrating the superiority of the hybrid Kibria-Lukman estimator for the ZINBR model.

The structure of the remainder of the article is as follows: Section 2 explores the model of interest and presents a theoretical comparison of the proposed estimators, including a discussion on newly proposed estimators. Section 3 outlines the methodology and results of the Monte Carlo simulation study. Section 4 provides an empirical analysis using real-world data to illustrate the application of the proposed estimators. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary of key findings and final remarks.

Zero-inflated negative binomial regression model

The ZINBR model is designed to handle count data characterized by both an excess of zeros and over-dispersion. In this model, the response variable \(Y_i\) (for \(i = 1, \ldots , n\)) is distributed according to a Zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) distribution, which integrates two components: with probability \(\vartheta _i\), \(Y_i\) equals zero; with probability \(1 - \vartheta _i\), \(Y_i\) follows a Negative Binomial (NB) distribution with mean \(\mu _i\) and dispersion parameter \(\nu > 0\). The probability mass function of the ZINB distribution is expressed as:

where \(\Gamma (.)\) denotes the gamma function, \(0< \vartheta _i< 1\), \(\mu _i > 0\), and \(\nu > 0\). The model uses a log link function for the count component and a logit link function for the zero-inflation component:

where \(x_i = (1, x_{i1}, \ldots , x_{i(p-1)})^T\) and \(z_i = (1, z_{i1}, \ldots , z_{i(q-1)})^T\) are the vectors of predictors for the count and zero-inflation components, respectively. The parameter vector \(\beta = (\beta _0, \beta _1, \ldots , \beta _{p-1})^T\) corresponds to the count component and is of dimension \(p \times 1\), while the parameter vector \(\gamma = (\gamma _0, \gamma _1, \ldots , \gamma _{q-1})^T\) corresponds to the zero-inflation component and is of dimension \(q \times 1\).

The mean and variance of \(Y_i\) given \(x_i\) are:

As \(\nu \rightarrow 0\), the ZINB model simplifies to the Zero-Inflated Poisson (ZIP) model. The log-likelihood function for a sample \(y = (y_1, y_2, \ldots , y_n)\) is:

where \(I(.)\) denotes the indicator function that equals 1 if \(y_i = 0\) and 0 otherwise. Similarly, \(I(y_i > 0) = 1 - I(y_i = 0).\)

The partial derivatives of the log-likelihood function with respect to \(\beta _j\) and \(\gamma _t\) are:

where these derivatives are nonlinear in \(\beta _j\) and \(\gamma _t\). Consequently, MLEs are obtained using numerical optimization techniques such as Expectation-Maximization (EM) and Newton-Raphson methods. After convergence, the MLE for \(\beta\) is given by:

where \(D = X^T \hat{W} {X}\), \(\hat{W} = \text {diag}(\text {var}(\hat{\mu }))\), and \(\hat{\mu }_i = \exp (x_i^T \hat{\beta })\). The MMSE and MSE are computed as:

where \(\nu ^2 = \frac{1}{n - p} \sum _{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{\mu }_i)^2\) and \(\Psi = \text {diag}(\psi _1, \psi _2, \ldots , \psi _p)\), with \(\psi _j\) representing the eigenvalues of \(D\) ordered such that \(\psi _1> \psi _2> \ldots> \psi _p > 0\). The matrix \(Q\) is the orthogonal matrix composed of the eigenvectors of \(D\).

Zero-inflated negative binomial ridge estimator

Multicollinearity is a significant issue in coefficient estimation, potentially resulting in unreliable estimates. When multicollinearity is present, the MLE may be ineffective, leading to inflated variances and standard errors. To mitigate these problems, Yüzbaşi and Asar32 developed the zero-inflated negative binomial ridge regression estimator (ZINBRRE) as follows:

where \(k\) represents the ridge parameter and \(I_p\) is the \(p \times p\) identity matrix. When \(k = 0\), the ZINBRRE \((\hat{\beta }_{\text {k}})\) reduces to the ZINBMLE \((\hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}} )\). Conversely, for \(k > 0\), \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {k}}\) is typically smaller in magnitude compared to \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}}\).

The bias vector, variance-covariance matrix for \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {k}}\) are specified as follows:

Yüzbaşi and Asar32 defined MMSE and MSE for ZINBRRE \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {k}}\) as follows:

The MSE of the \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {k}}\) is derived by taking the trace of Eq.(13), expressed as:

where \(\text {tr}(.)\) denotes the trace of the matrix and the matrix \(\Psi _k\) is defined as \(\text {diag}(\psi _1 + k, \psi _2 + k, \ldots , \psi _p + k)\).

Zero-inflated negative binomial Liu estimator

Building on Liu’s13 methodology, Akram et al.28 introduced the Liu estimator for the zero-inflated negative binomial regression model as an alternative to the ridge estimator. This method, known as the zero-inflated negative binomial Liu estimator (ZINBLE), addresses multicollinearity using a shrinkage technique. This technique enhances the stability and reliability of parameter estimates and is defined by:

where \(d\) represent Liu parameter. If \(d=1\) then \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {d}}= \hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}}\).

The bias vector, variance-covariance matrix for \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {d}}\) are given by:

Based on the previous equation the MMSE and MSE for \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {d}}\) are obtained as:

The MSE of the \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {d}}\) is given by taking the trace of Eq. (18) as:

Zero-inflated negative binomial Kibria-Lukman estimator

Akrama et al.28 introduced the zero-inflated negative binomial Kibria-Lukman estimator (ZINBKLE) as a specialized method to tackle multicollinearity in zero-inflated negative binomial regression models. Building on the work of Kibria and Lukman22, this estimator depends on one parameter \(K\) and offers an alternative to traditional estimators that depend on a single parameter and are given by

where \(K\) represent the Kibria-Lukman parameter. When \(K = 0\), the ZINBKLE \((\hat{\beta }_{\text {K}} )\) reduces to the ZINBMLE \(( \hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}} )\).

The bias vector and variance-covariance matrix of \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {K}}\) are as follows:

Using Eqs. (21), (22) Akrama et al.28 defined the MMSE and MSE for the ZINBKLE \((\hat{\beta }_{\text {K}} )\) as:

where the matrix \(\Psi _{-K} = \text {diag}(\psi _1 -K, \psi _2 - K, \ldots , \psi _p - K)\) and \(\Psi _{K} = \text {diag}(\psi _1 +K, \psi _2 + K, \ldots , \psi _p + K)\). The MSE of \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {K}}\) is given by taking the trace of Eq.(23) as follows:

Zero-inflated negative binomial modified ridge-type estimator

Akram et al.30 introduced a zero-inflated negative binomial modified ridge-type estimator (ZINBMRTE) with two parameters \((k_m, d_m)\) to address multicollinearity in the ZINBR model, defined as follows:

where \(k_m\text { and } d_m\) are the modified ridge-type parameters. If \(d_m=0\) then \(\hat{\beta }_{k_m, d_m}=\hat{\beta }_{\text {k}}\) and if \(k_m, d_m=0\) then \(\hat{\beta }_{k_m, d_m}=\hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}}\).

The bias vector and the variance-covariance matrix of ZINBMRTE \(\hat{\beta }_{k_m, d_m}\) are as follows:

Using Eqs. (26), (27) Akrama et al.30 defined the MMSE and MSE for the ZINBMRTE (\(\hat{\beta }_{k_m, d_m}\)) as:

where matrix \(\Psi _m = \text {diag}(\psi _1 + k_m(1+d_m), \psi _2 + k_m(1+d_m), \ldots , \psi _p + k_m(1+d_m))\) . The MSE of the \(\hat{\beta }_{k_m, d_m}\) is obtained by taking the trace of Eq. (28) and given by:

Proposed estimator

Building upon the work of Shewa and Ugwuowo24, Alrweili31 introduced a hybrid estimator for Poisson regression models. This method effectively combines the advantages of the Kibria-Lukman estimator with those of a modified ridge-type estimator (MRTE). The central innovation lies in replacing the (\(\hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}}\)) used in the Kibria-Lukman framework with the (\(\hat{\beta }_{\text {MRTE}}\)). Expanding on this concept, the paper proposes a hybrid Kibria-Lukman estimator for the ZINBR model, known as the zero-inflated negative binomial hybrid Kibria-Lukman estimator (ZINBHKLE). The formulation of ZINBHKLE is presented as follows:

where \(k_*\) and \(d_*\) are the hybrid Kibria Lukman parameters, and \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}\) returns to \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}}\) if \(k_{*}=0,d_*=0\).

The bias vector and the variance-covariance matrix of the ZINBHKLE \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}\) are defined as:

The MMSE and MSE of \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}\) are obtained using Eqs. (31), (32) as follows:

The MSE of \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}\) are obtained by take the trace of \(\text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*})\) as follows:

Theoretical comparison of estimators using MMSE and MSE

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed estimator, we conduct a comparison of the MMSE and MSE for the ZINBHKLE against other estimators, including ZINBMLE, ZINBRRE, ZINBLE, ZINBKLE, and ZINBMRTE, within the context of the ZINBR model. This comparison is grounded in theoretical results, providing a rigorous assessment of the proposed estimator performance.

Lemma 1

Given that \(B\) is a positive definite matrix, \(s\) is a positive constant, and \(\delta\) is a vector of nonzero constants, the inequality \(sB - \delta \delta ^T > 0\) holds if and only if \(\delta ^T B \delta < s\).33.

Theorem 1

Under ZINBR model, \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}\) outperforms \(\hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}}\) iff the following condition is satisfied: \(\text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}}) - \text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}) > 0\), where \(k_{*} > 0\), \(0<d_{*} < 1\) .

Proof

Using Eqs. (8) and (33), the difference between the MMSE of ZINBMLE and ZINBHKLE is given by

Eq. (35) can be expressed using the MSE as:

The matrix \((\Psi ^{-1}-\Psi _{k}^{-1} \Psi _{-k}\Psi ^{-1}_m\Psi ^{-1}_m\Psi _{-k}\Psi _{k}^{-1})\) is pd if \(({\psi }_j+k_{*})^2(\psi _j+k_{*}(1+d_{*}))^2-\psi _j^2({\psi }_j-k_{*})^2 > 0\), which is equivalent to \(({\psi }_j+k_{*})^2(\psi _j+k_{*}(1+d_{*}))^2 >\psi _j^2({\psi }_j-k_{*})^2\) being non-negative. Therefore, if \(k_{*} > 0\) and \(0<d_{*} < 1\), the proof is completed by Lemma 1. \(\square\)

Theorem 2

Under ZINBR model, \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}\) outperforms \(\hat{\beta }_{k}\) iff the following condition is satisfied: \(\text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{k}) - \text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}) > 0\), where \(k_{*},~k > 0\), and \(0<d_{*} < 1\).

Proof

Using Eqs. (13) and (33), the difference between the MMSE of ZINBRRE and ZINBHKLE is given by

Eq. (37) can be expressed using the MSE as:

The matrix \((\Psi _k^{-1}\Psi \Psi _k^{-1}-\Psi _{k}^{-1} \Psi _{-k}\Psi ^{-1}_m\Psi ^{-1}_m\Psi _{-k}\Psi _{k}^{-1})\) is pd if \(({\psi }_j+k_{*})^2(\psi _j+k_{*}(1+d_{*}))^2-(\psi _j+k)^2({\psi }_j-k_{*})^2 > 0\), which is equivalent to \(({\psi }_j+k_{*})^2(\psi _j+k_{*}(1+d_{*}))^2>(\psi _j+k)^2({\psi }_j-k_{*})^2\) being non-negative. Therefore, if \(k_{*},~k > 0\), and \(0<d_{*} < 1\), the proof is completed by Lemma 1. \(\square\)

Theorem 3

Under ZINBR model, \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}\) outperforms \(\hat{\beta }_{d}\) iff the following condition is satisfied: \(\text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{d}) - \text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}) > 0\), where \(k_{*} > 0\), \(0<d < 1\), and \(0<d_{*} < 1\).

Proof

Using Eqs. (18) and (33), the difference between the MMSE of ZINBLE and ZINBHKLE is given by

Eq. (39) can be expressed using the MSE as

The matrix \((\Psi +I_p)^{-1}(\Psi +dI_p) \Psi ^{-1} (\Psi +dI_p)(\Psi +I_p)^{-1}-\Psi _{k}^{-1} \Psi _{-k}\Psi ^{-1}_m\Psi ^{-1}_m\Psi _{-k}\Psi _{k}^{-1})\) is pd if \({(\psi }_j+d)^2({\psi }_j+k_{*})^2(\psi _j+k_{*}(1+d_{*}))^2-\psi _j^2(\psi _j+1)^2({\psi }_j-k_{*})^2 > 0\), which is equivalent to \({(\psi }_j+d)^2({\psi }_j+k_{*})^2(\psi _j+k_{*}(1+d_{*}))^2>\psi _j^2(\psi _j+1)^2({\psi }_j-k_{*})^2\) being non-negative. Therefore, if \(k_{*} > 0\), \(0<d_{*} < 1\) and \(0>d>1\) , the proof is completed by Lemma 1. \(\square\)

Theorem 4

Under ZINBR model, \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}\) outperforms \(\hat{\beta }_{K}\) iff the following condition is satisfied: \(\text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{K}) - \text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}) > 0\), where \(k_{*},K > 0\) and \(0<d_{*} < 1\).

Proof

Using Eqs. (23) and (33), the difference between the MMSE of ZINBKLE and ZINBHKLE is given by

Eq. (41) can be expressed using the MSE as:

The matrix \((\Psi _k^{-1} \Psi _{-k} \Psi ^{-1} \Psi _{-k}\Psi _k^{-1}-\Psi _{k}^{-1} \Psi _{-k}\Psi ^{-1}_m\Psi ^{-1}_m\Psi _{-k}\Psi _{k}^{-1})\) is pd if \({(\psi }_j-K)^2({\psi }_j+k_{*})^2(\psi _j+k_{*}(1+d_{*}))^2-\psi _j^2(\psi _j+K)^2({\psi }_j-k_{*})^2 > 0\), which is equivalent to \({(\psi }_j-K)^2({\psi }_j+k_{*})^2(\psi _j+k_{*}(1+d_{*}))^2>\psi _j^2(\psi _j+K)^2({\psi }_j-k_{*})^2\) being non-negative. Therefore, if \(k_{*} > 0\), \(0<d_{*} < 1\), and \(K > 0\) the proof is completed by Lemma 1. \(\square\)

Theorem 5

Under ZINBR model, \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}\) outperforms \(\hat{\beta }_{k_m,d_m}\) iff the following condition is satisfied: \(\text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{k_m,d_m}) - \text {MMSE}(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}) > 0\), where \(k_{*},k_m > 0\), \(0<d_m < 1\), and \(0<d_{*} < 1\).

Proof

Using Eqs. (28) and (33), the difference between the MMSE of ZINBMRTE and ZINBHKLE is given by

Eq. (43) can be expressed using the MSE as:

The matrix \((\Psi _m^{-1} \Psi \Psi _m^{-1}-\Psi _{k}^{-1} \Psi _{-k}\Psi ^{-1}_m\Psi ^{-1}_m\Psi _{-k}\Psi _{k}^{-1})\) is pd if \(({\psi }_j+k_{*})^2(\psi _j+k_{*}(1+d_{*}))^2-(\psi _j+k_m(d_m+1))^2({\psi }_j-k_{*})^2 > 0\), which is equivalent to \(({\psi }_j+k_{*})^2(\psi _j+k_{*}(1+d_{*}))^2>(\psi _j+k_m(d_m+1))^2({\psi }_j-k_{*})^2\) being non-negative. Therefore, if \(k_{*},k_m > 0\), \(0<d_{*} < 1\), and \(0>d_m>1\), the proof is completed by Lemma 1. \(\square\)

Determining the values of the estimator parameters

Following the approach of AlTaweel & Algamal3 and Yüzbaşi & Asar32, the ZINBRRE parameter values are defined as:

Following the work of Akram et al.28, we determine the ZINBLE and ZINBKLE parameters as:

According to Akram et al.30 and Lukman et al.34, the ZINBMRTE parameters are given by:

For the ZINBHKLE parameter, set \(\hat{d}_* = \hat{d}_m\) and calculate:

The proposed parameters are:

Monte carlo simulation

This section outlines a Monte Carlo simulation study aimed at comparing the proposed estimator (ZINBHKLE) with existing estimators, specifically the ZINBMLE, ZINBRRE, ZINBLE, ZINBKLE, and ZINBMRTE. The comparison is performed under various scenarios, including different levels of multicollinearity, numbers of explanatory variables, and sample sizes. Simulations are carried out using R software and the “pscl” package.

Simulation layout

The following details the experiment’s layout:

-

1.

In the simulation study, the regression coefficients \(\beta _0=1\) and \(\beta _1, \beta _2, ..., \beta _{p-1}\) are constrained to satisfy the following normalization condition35:

$$\sum _{h=1}^{p-1} \beta _h^2 = 1.$$ -

2.

The explanatory variables are generated to incorporate correlation among them using the following formula36,37:

$$x_{ij} = \sqrt{1 - \rho ^2} \, z_{ij} + \rho \, z_{ij}, \quad i=1,\ldots ,n, \, j=1,\ldots ,p,$$where \(x_{ij}\) denotes the j-th explanatory variable for the i-th observation, \(z_{ij}\) are independent standard normal pseudo-random numbers, and \(\rho\) represents the correlation parameter between variables.

This approach ensures that the generated explanatory variables \(x_{i1}, x_{i2}, \ldots , x_{ip}\) exhibit the desired level of correlation. Different values of \(\rho ^2\) (e.g. 0.75, 0.80, 0.85, 0.90, 0.95, and 0.99) are used in various simulation scenarios.

-

3.

The study examines four different sample sizes (\(n = 30, 75, 150, 200, 300, 400, 500\)) and three different numbers of regressors (\(p = 4, 7, 10\)).

-

4.

The response variable is generated from a ZINB distribution with an overdispersion parameter \(\nu = 0.5\). This is achieved using the ‘rzinb‘ function from the ‘extraDistr‘ package in R.

-

5.

Fit the ZINB model to the data using the ‘zeroinfl‘ function from the ‘pscl‘ package in R with the ‘dist = “negbin”‘ option. This allows for modeling the zero-inflation and count components of the response variable.

-

6.

The performance of the estimators is assessed using two metrics: MSE and MAE. The simulation study is replicated 5000 times to ensure robust results. The metrics are computed as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {MSE}(\hat{\beta })= & \frac{1}{5000} \sum _{l=1}^{5000} \left( \hat{\beta }^{(l)} - \beta \right) ^T \left( \hat{\beta }^{(l)} - \beta \right), \\ \text {MAE}(\hat{\beta })= & \frac{1}{5000} \sum _{l=1}^{5000} \left| \hat{\beta }^{(l)} - \beta \right|. \end{aligned}$$where \(\hat{\beta }^{(l)}\) denotes the estimated coefficient vector in the \(l\)-th replication, and \(\beta\) represents the true coefficient vector.

Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 show a Monte Carlo simulation study comparing the performance of the proposed ZINBHKLE estimator with several existing estimators (ZINBMLE, ZINBRRE, ZINBLE, ZINBKLE, and ZINBMRTE). The study offered a detailed understanding of how these estimators behave under different conditions of explanatory variables and sample sizes.

The MSE and MAE results reveal significant insights into the performance of various estimators under different sample sizes (n), multicollinearity levels (\(\rho ^2\)), and numbers of regressors (p).

Performance of Estimators:

-

1.

The simulation results show that both MSE and MAE get smaller as the sample size gets bigger for all the estimators. This makes sense because with more data, the estimates become more accurate and stable.

-

2.

When \(\rho ^2\) (a measure of multicollinearity) increases, the MSE also increases for all estimators. This means that as the relationship between the explanatory variables gets stronger, it becomes harder to estimate the model accurately. This problem is especially noticeable with the MLE estimator.

-

3.

We tested models with 4 to 10 variables to see how increasing the number of variables affects multicollinearity. As expected, both MSE and MAE increased, showing that it becomes harder to estimate the model accurately when more correlated variables are added.

-

4.

MSE consistently decreases as sample size increases, especially under mild multicollinearity (\(\rho ^2 \le\) 0.85). Under severe multicollinearity (\(\rho ^2\ge\) 0.90), large samples help, but estimators like MLE still perform poorly without regularization. MLE MSE at \(\rho ^2\) = 0.75 drops from 0.44308 (n = 30) to 0.02244 (n = 500). At \(\rho ^2\) = 0.99, MLE MSE remains high (471.44 at n = 30, 1.23 at n = 500).

-

5.

Traditional estimators (like MLE) break down when \(\rho ^2 \ge\) 0.90. For \(\rho ^2\) = 0.75 or lower, the performance difference among estimators becomes marginal.

-

6.

ZINBMLE (\(\hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}}\)): This estimator tends to have higher MSE and MAE when the number of variables and multicollinearity increase. It performs worse in these cases, making it less reliable under high correlation.

-

7.

ZINBRRE (\(\hat{\beta }_{k}\)): This estimator usually has lower MSE and MAE than ZINBMLE, making it a more reliable option when multicollinearity is present.

-

8.

ZINBKLE (\(\hat{\beta }_{K}\)): This one often gives better results than ZINBMLE, ZINBLE, and ZINBRRE. It keeps MSE and MAE low even when the number of variables and multicollinearity are high, especially when using the \(\hat{K}_1\) version.

-

9.

ZINBMRTE (\(\hat{\beta }_{k_m,d_m}\)): This estimator performs very well across different values of p and \(\rho ^2\), often with lower MSE and MAE than ZINBKLE. It’s a good choice for handling multicollinearity.

-

10.

ZINBHKLE (\(\hat{\beta }_{k_*,d_*}\)): This estimator gives the best results in all scenarios, with the lowest MSE and MAE. It shows strong performance and is the most effective in dealing with multicollinearity among all the estimators tested.

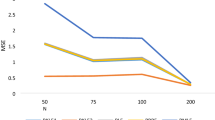

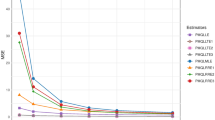

Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 illustrate the performance of various estimators in terms of MSE and MAE. Figures 2 and 4 show that ZINBHKLE consistently has the lowest MSE and MAE across different levels of multicollinearity, while MSE and MAE of all estimators increase significantly with higher \(\rho ^2\). Figures 1 and 3 demonstrate that MSE and MAE decrease with larger sample sizes, with ZINBHKLE maintaining the lowest MSE and MAE. Overall, ZINBHKLE outperforms other estimators in handling both multicollinearity and varying sample sizes.

In summary, the MLE is highly sensitive to multicollinearity, leading to increased MSE and MAE values. In contrast, the ZINBHKLE estimator, especially when incorporating various shrinkage parameters, consistently outperforms all other estimators. Therefore, we recommend the ZINBHKLE estimator for its robust and reliable performance, particularly in scenarios characterized by high but imperfect multicollinearity.

Applications

Demand for health care data

In this section, we evaluate the performance of ZINB estimators using the docvisits dataset, originally introduced by Riphahn et al.38 and later employed by Koç and Koç39. This dataset, focusing on German male individuals in 1994, is particularly well-suited for count data analysis as it includes the number of doctor visits as the response variable. With 14 explanatory variables and a sample size of \(n = 1812\), the dataset provides valuable insights into healthcare demand. It is publicly accessible through the zic package in R language.

The dataset comprises various socioeconomic and health-related factors that influence healthcare demand, particularly the number of doctor visits (response variable, \(y\)). Key explanatory variables include age (\(x_1\)), age squared (agesq, \(x_2\)), and health satisfaction (health, \(x_3\)), measured on a scale from 0 to 10. It also includes binary variables such as handicap status (\(x_4\)), marital status (married, \(x_5\)), employment status (employed, \(x_6\)), and public health insurance coverage (public, \(x_7\)). Additional variables include degree of handicap (hdegree, \(x_8\)), years of schooling (schooling, \(x_9\)), household income (hhincome, \(x_{10}\)), and indicators for self-employment (self, \(x_{11}\)), civil servant status (civil, \(x_{12}\)), blue-collar employment (bluec, \(x_{13}\)), and add-on health insurance (addon, \(x_{14}\)). Together, these variables provide a comprehensive overview of the factors influencing healthcare demand, making the dataset ideal for count data analysis.

The data, sourced from Koç and Koç39, was initially analyzed using a negative binomial regression model. The mean (2.95) is much lower than the variance (27.287), indicating overdispersion. However, we found a significant excess of zeros in the data-746 out of 1812 observations, or about 41.2%, are zeros as described in Fig. 5. This is much higher than expected for typical count data. Because of this high number of zeros, traditional count models like Poisson or negative binomial regression may not be suitable. Instead, a ZINBR model is better for handling the excess zeros and providing more accurate results.

Koç and Koç39 tested multicollinearity in this dataset using the correlation matrix, as illustrated in Fig.6, and the condition number is defined as the square root of the ratio of the largest to the smallest singular value of the matrix \(D\) and is equal to 3335.615. Their analysis revealed severe multicollinearity within the data, indicating that some explanatory variables are highly correlated with each other.

The MSEs for the estimators ZINBMLE, ZINBRRE, ZINBLE, ZINBKLE, ZINBMRTE, and ZINBHKLE are calculated according to Eqs. (9), (14), (19), (24), (29), and (34), respectively. Table 7 presents a comprehensive summary of the estimated coefficients and MSEs for various biased estimators applied to healthcare demand data, revealing significant performance disparities. The analysis shows that several biased estimators outperform the ZINBMLE, which serves as the benchmark with an MSE of 2.6271. In particular, the estimator \(\hat{\beta }_d\) demonstrates superior accuracy with a notably lower MSE of 1.7274. Furthermore, the ZINBHKLE estimator, especially with all parameters \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*}\), achieves even lower MSE values, reaching as low as 0.1979, indicating substantial potential for further enhancement with optimized parameter settings. Overall, the ZINBHKLE (\(\hat{k_*}_1\)) estimator exhibits the most favorable performance in terms of MSE, reflecting its optimal accuracy. Hence, researchers should employ the ZINBHKLE (\(\hat{k_*}_1\)) estimator when addressing issues of high but imperfect multicollinearity.

The results from the bias and MSE plots in Fig. 7 clearly show that the ZINBHKLE method performs exceptionally well compared to other estimators. It maintains a low bias while achieving the lowest MSE, especially as the value of k increases. This indicates that ZINBHKLE provides more accurate and stable parameter estimates, balancing the trade-off between bias and variance effectively. Its strong performance suggests that it is a reliable and robust choice for modeling complex data in ZINBRM, making it particularly useful in practical applications where precision matters.

Wildlife fish data

In this analysis, we examine the wildlife fish dataset, as utilized in previous studies by Saffari and Adnan40, AlTaweel and Algamal3, Zandi et al.26, and Akram et al.28, which is available at https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/stat/data/fish.csv. The dataset includes information from 250 groups of individuals who visited a state park with the intent of fishing. The primary challenge is the presence of excess zeros in the response variable, which represents the number of fish caught, as some visitors did not catch any fish. Additionally, there is no data on whether all visitors actively participated in fishing. The dataset contains the following variables: count (number of fish caught, y), nofish (whether the trip was solely for fishing, coded as 0 for no and 1 for yes, \(x_1\)), livebait (whether live bait was used, coded as 0 for no and 1 for yes, \(x_2\)), camper (whether a camper was brought, \(x_3\)), persons (total number of individuals in the group, \(x_4\)), and child (number of children present, \(x_5\)).

Akram et al.28, Zandi et al.26, and AlTaweel and Algamal3 have demonstrated that the wildlife fish dataset exhibits a significant proportion of excess zeros, with 132 out of 250 observations (52.8%) reporting zero fish caught as in Fig. 8. The condition number is defined as the square root of the ratio of the largest to the smallest singular value of the matrix \(D\) and is equal to 133.2941. They utilized the ZINBR model to analyze this dataset and found that the explanatory variables are highly multicollinear. Their analysis revealed severe multicollinearity issues among the variables, highlighting the need for careful consideration of this factor in the modeling process.

Table 8 presents the estimated coefficients and MSEs for different biased estimators applied to the wildlife fish dataset. The results reveal significant variation in performance among the estimators. Notably, the ZINBHKLE (\(\hat{\beta }_{k_*}\)) demonstrates the lowest MSE of 1.2924, indicating superior accuracy compared to other estimators, such as the MLE (\(\hat{\beta }_{\text {MLE}}\)) which has a higher MSE of 7.1654. The parameter estimates from \(\hat{\beta }_{k_*}\), especially those with \(\hat{k_*}_1\), contribute to its improved accuracy and lower MSE, highlighting it as the most effective estimator for this dataset.

Figure 9 shows that the ZINBHKLE method performs very well in reducing MSE compared to other methods, especially when k is more than 1. A lower MSE means the estimates are more accurate and consistent, which helps improve predictions and makes statistical results more reliable. This suggests that ZINBHKLE achieves a good balance between bias and variance, making it a strong and effective option for estimating parameters in ZINBRM.

Conclusion

This study presented a novel hybrid estimator named ZINBHKLE. This estimator employs two parameters and is particularly designed to enhance the performance of ZINBR models in the presence of multicollinearity. ZINBHKLE seeks to mitigate problems associated with multicollinearity and zero inflation in regression models by integrating components from established biased estimators. The suggested hybrid estimator underwent thorough assessment via theoretical comparisons and comprehensive Monte Carlo simulations. The simulations demonstrate that our suggested estimator consistently surpasses conventional approaches, including ZINBMLE, ZINBRRE, ZINBLE, ZINBKLE, and ZINBMRTE, particularly in contexts characterized by elevated multicollinearity. Our findings demonstrate that the new estimator yields more consistent and precise parameter estimations while also attaining reduced MSE and MAE in comparison to alternatives. The suggested estimator was used on real-world datasets, showcasing its practical efficacy and resilience. The application outcomes and simulation findings demonstrate enhanced efficacy in generating accurate parameter estimations. The suggested two-parameter hybrid estimator signifies a substantial progression in ZINBR modeling. It provides a significant alternative to conventional approaches, especially in intricate situations characterized by multicollinearity and zero inflation. Researchers and practitioners are urged to evaluate this novel estimator for enhanced accuracy and stability in parameter estimation inside zero-inflated negative binomial regression models. The suggested estimator successfully mitigates multicollinearity; yet, it has certain constraints. The performance may be contingent upon the selection of shrinkage parameters, necessitating meticulous decisions for the best outcomes. Moreover, its efficacy in small samples may be constrained, and it may not apply to all regression models. Future studies should examine its applicability across other modeling frameworks and investigate data-driven approaches for picking tuning parameters. Future endeavors could include the development of a robust iteration of the proposed estimator to mitigate the effects of multicollinearity and outliers, as delineated by Dawoud and Abonazel41, Dawoud et al.42, and Abonazel and Dawoud43. Furthermore, diagnostic metrics such as Cook’s distance and DFFITS may be included for the proposed estimator, following the research of Dawoud and Eledum44. Moreover, the suggested estimator may be adapted for other regression models.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Hilbe, J. M. Negative binomial regression (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Greene, W. H. Accounting for excess zeros and sample selection in poisson and negative binomial regression models. NYU working paper no. EC-94-10, (1994).

Al-Taweel, Y. & Algamal, Z. Some almost unbiased ridge regression estimators for the zero-inflated negative binomial regression model. Periodicals of Engineering and Natural Sciences 8(1), 248–255 (2020).

Alin, A. Multicollinearity. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: computational statistics 2(3), 370–374 (2010).

García, C. B., Salmerón, R., García, C. & García, J. Residualization: justification, properties and application. Journal of Applied Statistics 47(11), 1990–2010 (2020).

Gómez, R. S., García, C. G., & Reina, G. H. Generalized ridge regression: Applications to nonorthogonal linear regression models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.06171, (2025).

Hoerl, A. E. & Kennard, R. W. Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics 12(1), 55–67 (1970).

Kibria, B. M. G. Performance of some new ridge regression estimators. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation 32(2), 419–435 (2003).

Khalaf, G. & Shukur, G. Choosing ridge parameter for regression problems. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods 34(5), 1177–1182 (2005).

Muniz, G., & Kibria, B. M. G. On some ridge regression estimators: An empirical comparisons. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation®, 38(3):621–630, (2009).

García García, C., Salmeron Gomez, R., & García Pérez, J. A review of ridge parameter selection: minimization of the mean squared error vs. mitigation of multicollinearity. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, 53(8):3686–3698, (2024).

Abonazel, M. R., Alzahrani, A. R.h R., Saber, A. A., Dawoud, I., Tageldin, E., & Azazy, A. R. Developing ridge estimators for the extended poisson-tweedie regression model: Method, simulation, and application. Scientific African, 23:e02006, (2024).

Liu, K. A new class of blased estimate in linear regression. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 22(2), 393–402 (1993).

Özkale, M. R. & Kaciranlar, S. The restricted and unrestricted two-parameter estimators. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 36(15), 2707–2725 (2007).

Liu, K. Using liu-type estimator to combat collinearity. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 32(5), 1009–1020 (2003).

Abonazel, M. R., Dawoud, I., Awwad, F. A. & Tag-Eldin, E. New estimators for the probit regression model with multicollinearity. Scientific African 19, e01565 (2023).

Dawoud, I., Abonazel, M. R. & Awwad, F. A. Modified liu estimator to address the multicollinearity problem in regression models: a new biased estimation class. Scientific African 17, e01372 (2022).

Salmerón-Gómez, R., García-García, C. B., & Rodríguez-Sánchez, A. Enlarging of the sample to address multicollinearity. Computational Economics, pages 1–23, (2025).

Dawoud, I., Abonazel, M. R. & Awwad, F. A. Generalized Kibria-Lukman estimator: method, simulation, and application. Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics 8, 880086 (2022).

Lukman, A. F., Ayinde, K., Binuomote, S. & Clement, O. A. Modified ridge-type estimator to combat multicollinearity: Application to chemical data. Journal of Chemometrics 33(5), e3125 (2019).

Dawoud, I., Abonazel, M. R., Awwad, F. A. & Tag Eldin, E. A new tobit ridge-type estimator of the censored regression model with multicollinearity problem. Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics 8, 952142 (2022).

Kibria, A. F., B. M. G. and Lukman et al. A new ridge-type estimator for the linear regression model: Simulations and applications. Scientifica, 2020, (2020).

Dawoud, I. & Kibria, B. M. G. A new biased estimator to combat the multicollinearity of the gaussian linear regression model. Stats 3(4), 526–541 (2020).

Shewa, G. A. & Ugwuowo, F. I. A new hybrid estimator for linear regression model analysis: computations and simulations. Scientific African 19, e01441 (2023).

Akram, M. N., Abonazel, M. R., Amin, M., Kibria, B. M. G. & Afzal, N. A new stein estimator for the zero-inflated negative binomial regression model. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 34(19), e7045 (2022).

Zandi, Z., Bevrani, H. & Arabi, R. Improved shrinkage estimators in zero-inflated negative binomial regression model. Hacettepe Journal of Mathematics and Statistics 50(6), 1855–1876 (2021).

Dawoud, I. & Eledum, H. New stochastic restricted biased regression estimators. Mathematics 13(1), 15 (2024).

Akram, M. N., Amin, M., Afzal, N., & Kibria, B. M. G. Kibria–lukman estimator for the zero inflated negative binomial regression model: theory, simulation and applications. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, pages 1–17, (2023).

Zandi, Z., R. Arabi B., & Bevrani, H. Liu-type shrinkage strategies in zero-inflated negative binomial models with application to expenditure and default data. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, pages 1–31, (2022).

Akram, M. N., Afzal, N., Amin, M., & Batool, A. Modified ridge-type estimator for the zero inflated negative binomial regression model. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, pages 1–18, (2023).

Alrweili, H. Kibria-lukman hybrid estimator for handling multicollinearity in poisson regression model: Method and application. International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences 2024(1), 1053397 (2024).

Yüzbaşi, B., Asar, A.: Ridge type estimation in the zero-inflated negative binomial regression. Econometrics: Methods & Applications, page 93, (2018).

Farebrother, R. W. Further results on the mean square error of ridge regression. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), pages 248–250, (1976).

Lukman, A. F., Aladeitan, B., Ayinde, K. & Abonazel, M. R. Modified ridge-type for the poisson regression model: simulation and application. Journal of Applied Statistics 49(8), 2124–2136 (2022).

Dawoud, I. New biased estimators for the conway-maxwell-poisson model. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 95(1), 117–136 (2025).

Abdelwahab, M. M., Abonazel, M. R., Hammad, A. T. & El-Masry, A. M. Modified two-parameter liu estimator for addressing multicollinearity in the poisson regression model. Axioms 13(1), 46 (2024).

Dawoud, I. A new improved estimator for the gamma regression model. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, pages 1–12, (2025).

Riphahn, R. T., Wambach, A. & Million, A. Incentive effects in the demand for health care: a bivariate panel count data estimation. Journal of applied econometrics 18(4), 387–405 (2003).

Koç, T. & Koç, H. A new effective jackknifing estimator in the negative binomial regression model. Symmetry 15(12), 2107 (2023).

Saffari, S. E. & Adnan, R. Parameter estimation on zero-inflated negative binomial regression with right truncated data. Sains Malaysiana 41(11), 1483–1487 (2012).

Dawoud, I. & Abonazel, M. R. Robust dawoud-kibria estimator for handling multicollinearity and outliers in the linear regression model. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 91(17), 3678–3692 (2021).

Dawoud, I., Awwad, F. A., Tag Eldin, E. & Abonazel, M. R. New robust estimators for handling multicollinearity and outliers in the poisson model: methods, simulation and applications. Axioms 11(11), 612 (2022).

Abonazel, M. R. & Dawoud, I. Developing robust ridge estimators for poisson regression model. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 34(15), e6979 (2022).

Dawoud, I., & Eledum, H. Detection of influential observations for the regression model in the presence of multicollinearity: Theory and methods. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods, pages 1–26, (2025).

Acknowledgements

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R515), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have worked equally to write and review the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almulhim, F.A., Nagy, M., Hammad, A.T. et al. New two parameter hybrid estimator for zero inflated negative binomial regression models. Sci Rep 15, 21239 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06116-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06116-4