Abstract

This study aimed to develop a reliable and explainable predictive model for illicit drug use (IDU). The model uses a machine learning (ML) algorithm to predict IDU using hematological differences between illicit drug users (IDUr) and non-users (n-IDUr). A total of 286 IDUr and 302 n-IDUr were included in this study. By comparing the IDU prediction performance of eight ML models, an explainable LGB model with 13 features was established, which could accurately predict IDU in both internal (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.925) and external (AUC = 0.915) validation sets. Using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to explain our prediction model, we found that chloride (Cl), β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), and anion gap (AG) had a strong influence on the results predicted. Many of the features used for model training are interrelated, serving as important indicators of kidney, liver, and thyroid function in hematological examinations. Combining these manifestations can enable doctors to perform preliminary screening for IDU while conducting corresponding organ examinations in ordinary patients, which has a profound importance in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Illicit drug use (IDU) has emerged as a major social problem globally1,2. According to the World Drug Report, more than 296 million people worldwide use illicit drugs, and approximately 6,00,000 people die each year directly from IDU. Illicit drugs include amphetamines and opioids, which are used as medical drugs in appropriate doses3,4. However, their addictive nature, when used excessively, often leads to dependency and addiction problems. People addicted to illicit drugs have a higher risk of premature death than the general population5, and tend to deny using them6,7. Therefore, prompt detection and intervention for IDU using external methods are crucial.

Currently, IDU detection methods involve testing the hair, urine, or blood of suspected illicit drug users (IDUr) to detect residual drugs or drug metabolites8,9,10,11. However, these methods have limitations: hair testing cannot be widely used in community hospitals because of its high cost, while urine and blood tests are limited by the duration that drugs and their metabolites remain in the body12 and have high timeliness requirements13. To address these challenges, many studies have focused on exploring the differences between the body fluids, particularly blood, of IDUr and those of non-users (n-IDUr) and finding more efficient methods to identify IDU by analyzing various indicators. Simonovska et al.14 extracted and compared blood samples from heroin users and healthy subjects and found deviations in immune indicators such as serum immunoglobulin and complement C3, C4. Guleken et al.15 used infrared spectroscopy to show that serum albumin (Alb), triglyceride (Tg), and total cholesterol (Tc) levels decreased with increasing duration of heroin use. Ciubotariu et al.16,17 observed lower zinc levels in the serum, plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid of opioid users compared to n-IDUr. Díaz-Flores Estévez et al.18 confirmed that opioid users had lower levels of retinol, \(\alpha\)-tocopherol, folic acid, and other indicators in the blood compared to n-IDUr. Additionally, many studies19,20,21 have reported considerable differences in routine blood indicators such as red blood cells, platelets, and neutrophils between IDUr and n-IDUr. Despite many important discoveries in the study of the blood characteristics of IDUr, predictive studies on IDU based on blood characteristics are limited. Most of these studies explored the differences between IDUr and n-IDUr and have not been implemented in clinical applications.

With the rise of artificial intelligence, Scholars are focusing on combining intelligent algorithms with clinical medicine to improve the efficiency of disease treatment22,23. Navid Kaboudi et al.23 evaluated the diagnostic performance and safety of ChatGPT in prioritizing patients according to urgency in emergency settings,demonstrating the potential of artificial intelligence alhorithms in clinical practice. At the same time, disease prediction methods based on machine learning (ML) have gradually attracted the attention of clinicians24,25,26. These algorithms can automatically learn key features from a small number of samples to complete disease prediction tasks. Compared to traditional statistical analysis methods based on large amounts of data, they have higher accuracy and effectively reduce costs. In addition, the prediction results of a stable and interpretable ML model can gain further recognition. In this study, we aimed to develop and validate a stable and interpretable ML model for efficient and reliable prediction of IDU.

Methods

Study population and data preprocessing

This study has been registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Register under the title “Drug abstinence and its control cohort study in Yunnan Province” (ChiCTR2100051931).The experimental group used in this study consisted of 244 IDUr from Kunming Drug Rehabilitation Institution. They underwent urine or blood tests between January 2021 and May 2023 for suspected IDU and were found to have abused opioids or amphetamines in the short term. As a control group, 252 n-IDUr from the same region who had never used illicit drugs (including for medical use) were selected. They had a similar age distribution and gender ratio as the experimental group to reduce their impact on the experiment. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (approval number 2021.L.2), and all participants provided written informed consent after they were informed of the purposes, processes, and potential risks associated with the study. All data were anonymized throughout the research process to ensure that the privacy of the participants was not breached. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Based on relevant research14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,27, 80 hematological indices that may be related to IDU were preselected for the study, and the collected raw sample data were preprocessed before subsequent analysis. Preprocessing was divided into three parts. First, abnormal sample values that deviate from the inner limit are regarded as missing values through central tendency analysis. Second, features with more than 25\(\%\)missing values were excluded. Finally, the missing values were filled with the mode. Details on the processing of outliers and missing values are given in the Supplementary Information.

Tables 1 and A1 summarize the characteristics of IDUr in the complete dataset. After excluding four samples, we standardized the sample data for each blood characteristic and calculated the P-value to reflect the difference between the two groups. As shown in Tables 1 and A1, there were 28 features with P < 0.001, suggesting a correlation between blood characteristics and IDU. Consequently, these 80 features were used to establish a prediction model.

Model development and comparison

All data from the experimental and control groups were randomly shuffled, with 80\(\%\) used as the training set and 20\(\%\) as the internal validation set. Eight ML models were trained to predict IDU: random forest (RF), gradient boosting machine (GBM), light-gradient boosting machine (LGB), logistic regression (LR), extreme gradient boosting (XGB), adaptive boosting (AdaBoost), support vector machine (SVM), and backpropagation neural network (BPNN). To ensure that all the models performed better on the blood dataset, the hyperparameters of each ML model were manually fine-tuned according to the ten-fold cross-validation results. The fine-tuning results are shown in Table 2. All unexplained training and validation experiments were performed using five-fold cross-validation to reduce the contingency caused by the division of the datasets.

The model’s predictive effect on IDU was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), precision, and recall. The AUC was used to evaluate the overall performance of the model. AUC is calculated based on the entire receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, thereby reducing the performance fluctuations caused by the model when processing datasets with imbalanced categories. Compared with accuracy, it can comprehensively reflect the model’s prediction ability. Precision and recall were used to measure the model’s ability to identify IDU.

In addition to comparing the overall performance of the eight ML models on the complete dataset, feature simplification experiments were conducted to improve the generalization ability of the models to reduce redundant linearly related and irrelevant features. The number of features in the training was limited based on the importance of each feature in each model. The prediction results of each model trained with different feature combination datasets were compared to further analyze the performance of each model on the blood dataset.

Additionally, we used an external dataset consisting of 50 n-IDUr and 42 IDUr from the Kunming Drug Rehabilitation Institution for external validation to avoid model overfitting. Simultaneously, to verify that the prediction model is not constrained by high timeliness, the IDUr in this external validation set had a different time span of IDU from the internal dataset, with the last instance of illicit drug use occurring between June 2023 and December 2023. To further verify the robustness and stability of the model, we analyzed its performance on the internal and external validation sets using repeated random subsampling cross-validation (RRSCV). RRSCV constructs training and test sets through multiple random subsamplings. During the training process of small-sample data, RRSCV can ensure that different training and test sets are obtained for each sampling, and this process is repeated multiple times to obtain more stable prediction and evaluation results through numerous calculations.

Finally, the internal and external datasets were integrated to train the final model. The model performance was comprehensively improved to achieve more efficient IDU prediction by analyzing its predicted probability distribution to adjust the classification threshold28. All models in this study were implemented based on the open-source machine learning library, Scikit-learn, and Python 3.9, and were trained on Intel Core i9-13900HX and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060.

Model explanation

A prediction algorithm based on the ML model is like a black box for clinicians. Its output results are not supported by practical evidence and are not convincing. Therefore, it is important to describe the ML model in detail.

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) is a unified framework29, and some studies have used it to explain the model24,26,30. SHAP not only explains the model based on the training set but also explains the prediction results of individual samples once they are input into the model. In the binary classification problem, the overall explanation of the model provides a unified standard for measuring the importance of each feature, which can associate all blood features with whether IDU occurs and outputs the contribution of all features to the prediction of positive and negative samples based on the classification labels of all samples in the training set. The local explanation based on a single sample provides a factual basis for the prediction results of a single sample and lists all blood features that push it to a positive classification (IDU) or negative classification (n-IDU) according to the contribution of each feature to achieve the purpose of targeted analysis.

In this study, we used both internal and external datasets to train the final IDU prediction model and used SHAP to perform a blood feature importance analysis on the prediction model to fully understand the facts used by the model when making predictions on the samples.

Results

Details of the IDU prediction model are shown in Fig. 1. First, eight ML models were trained and validated using internal datasets, and the features were simplified and screened based on their performance results. Subsequently, the models were validated using external validation sets to avoid overfitting and verify their stability. Finally, the best model was trained using a combination of internal and external datasets, and the SHAP method was used to explain the model both globally and locally.

Model development

This study included 496 participants. After blood collection, laboratory tests, and raw data preprocessing, four samples with too many missing values were excluded, and eight hyperparameter-tuned ML models were trained based on 80 features using a ten-fold cross-validation method. The effect of internal validation is shown in Fig. 2A, where the AUC was used to evaluate the model’s prediction effect on IDU. Among the eight models, the GBM (AUC = 0.8951) performed best, with the performance of the remaining models not significantly different from that of the GBM. Since all blood features were used for predictive training, there was a risk of overfitting and model performance may have been affected by the feature dimensions. In order to address these issues, a feature simplification experiment was performed on six models with a relatively good performance (Fig. 2A) to limit the number of features involved in the training.

From the analysis of differences between the two experimental groups (Table 1), 28 out of 80 features showed significant differences. SHAP was used to analyze the feature importance of each model and select the first 28 features for training. The number of features was gradually reduced according to their importance after each experiment. The results of the feature simplification experiment are shown in Fig. 2B and Table A2. It was observed that the best performance of each model was concentrated between 8 and 18 features, and when the first 13 features were used for training, most models showed the best performance. Throughout the experiment, the GBM showed the best performance (AUCmax = 0.9136), followed by XGB (AUCmax = 0.9099). The LR model demonstrated relatively stable performance (\(\Delta\)AUCmax = 0.0025), but its overall performance was poor, followed by LGB (\(\Delta\)AUCmax = 0.0195), GBM (\(\Delta\)AUCmax = 0.0214), and RF (\(\Delta\)AUCmax = 0.0226), all having better overall performance. The results of the feature-simplification experiments are presented in Table A2.

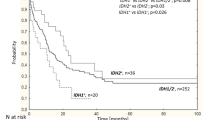

Based on the best performance and stability of each model, we selected the top 13 features for internal and external validation of the LGB, AdaBoost, GBM, and RF models. The validation was performed using 50 random subsampling cross-validations. The results are shown in Fig. 2C and Table 3. Based on the AUC and stability of the model in the internal and external validation sets, LGB outperformed the other four models. The LGB model had better average performance and a higher upper limit on the internal and external validation sets, with a small performance difference between the two (\(\Delta\)AUC = 0.0109), indicating that the model was not overfitted after training on the internal data set. In terms of stability, a comprehensive comparison of the validation results of the 50 experiments showed that LGB has a relatively concentrated AUC value on the external validation set, which indicates that LGB has a more stable prediction ability and higher credibility when facing different sample inputs. Finally, Fig. 2D shows the AUC, F1, sensitivity, and specificity of the LGB model, as well as the error range of each evaluation indicator. The LGB model exhibited higher accuracy in predicting positive samples, indicating that it can identify as many IDUr as possible from all subjects, aligning with our study’s objective.

Performance of ML models to predict IDU. (A) ROC curves for all ML models. (B) Internal validation set performance of ML models with a limited number of training features. (C) The overall performance of the LGB model and its standard error in 50 random subsampling cross validation. (D) The performance of RF, LGB, AdaBoost, and GBM models trained with the first 13 features on the internal and external validation sets based on RRSCV, where the box length is the distance between quartiles Q1 and Q3, the dotted line is the mean, the whisker is the inner limit (1.5 times the interquartile range), and the circle is the outlier. IDU: illicit drug use. AUC: the area under the receiver-operating-characteristic curve. RF: random forest. GBM: gradient boosting machine. LGB: light gradient boosting machine. LR: logistic regression. XGB: eXtreme gradient boosting. AdaBoost: adaptive boosting. SVM: support vector machine. BPNN: Backpropagation neural network.

Final model optimization

The final IDU prediction model was trained using LGB on 582 samples from the internal and external datasets. The training included 13 features: chloride (Cl), \(\beta\)-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), anion gap (AG), retinol-binding protein (RBP), bicarbonate (HCO3), free triiodothyronine (FT3), anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies (aTPO), serum cystatin C (CYSC), free thyroxine (FT4), folate (Folate), uric acid (UA), anti-thyroglobulin antibodies (aTG), and fasting blood glucose (FBG). The data were divided into 50 training and validation sets using 50 random subsampling cross-validation methods to analyze the performance of the final model and perform targeted optimization. The validation set of each dataset contained 57 positive samples (IDU) and 60 negative samples (n-IDU), while the training set contained 227 positive and 238 negative samples, ensuring that all groups were composed of different samples with the same distribution of positive and negative samples.

The experiment used AUC, accuracy, F1 score, sensitivity, and specificity to evaluate the model’s performance. Although AUC is the most objective evaluation metric for binary classification models, accuracy provides an intuitive measure of the actual performance of the IDU prediction model. Additionally, the F1 score offers a more balanced assessment of classification accuracy, especially when the sample sizes of the two categories are unequal. Figure 3A shows the average validation performance of the final model when the binary classification threshold (BCT) is 50\(\%\). The model achieved an accuracy of 86.0\(\%\) on the verification set. Compared with the training and validation performance on the internal dataset (Fig. 2D), the AUC of the final model was higher, but its accuracy, F1, sensitivity, and specificity were all reduced; therefore, we analyzed the prediction probability distribution of the LGB model on the validation set.

Performance analysis of the final model. (A) Overall performance of the final model. (B) The predicted probability distribution of the final model on the validation set. (C) Prediction probability distribution of FN and TN in confusion matrix. (D) Confusion matrix of cross validation with 50 random subsampling applied to the final model.

As shown in Fig. 3B, the model’s prediction probability for the validation set samples was mainly concentrated around 10 and 80\(\%\), and the closer the prediction probability was to 50\(\%\), the lower the model’s confidence in the prediction result and vice versa. The sparsest area of the prediction probability distribution was around 30\(\%\), which is not the usual BCT location. This indicated that there were too many samples with low confidence (prediction probability of approximately 50\(\%\)) during the validation of the model, which led to a decrease in the overall performance of the model, necessitating further optimization and adjustment.

As shown in Fig. 3C, analyzing the confusion matrix of the final model revealed that the probability of TN (samples correctly predicted as negative) was mainly concentrated between 0 and 10\(\%\), and the probability of FN (samples incorrectly predicted as negative) was mainly concentrated between 30 and 50\(\%\). This shows that the final model can accurately predict most negative samples with high confidence; however, for a small number of positive samples, the model misclassifies them as negative with low confidence. Since TN in the range of 20–50\(\%\) is less than FN, it was considered to adjust the BCT of the LGB model to sacrifice some of the accuracy of negative predictions in exchange for a relatively higher accuracy of positive predictions and improve the confidence of the overall prediction of the model.

When evaluating the comprehensive performance of the model, as the AUC is calculated through the classification probability value and is not affected by the BCT and the F1 score can comprehensively judge the performance of the model based on the prediction accuracy of positive and negative samples, we adjusted the BCT of the final model to maximize its F1 score on the validation set to enhance the prediction ability of IDU.

Figure 4A shows the dynamic changes in the model performance when adjusting the BCT. When BCT = 23\(\%\), the model had the highest F1 score (F1 = 0.878); therefore, the output probability of the model was mapped. As shown in Fig. 4B, after mapping the original prediction probabilities of 0–23\(\%\) and 23–100\(\%\) to 0–50\(\%\) and 50–100\(\%\), respectively, the new model predicted more probabilities in the high confidence area compared to the original model. hlComparing Fig. 3C and 4C reveals that the prediction accuracy of the new model in the validation set reached 86.5\(\%\), which is 0.5\(\%\) higher than before the improvement, and the new model saw a 0.009 increase in F1 score, a 0.044 increase in sensitivity, and a 0.032 decrease in specificity. The confusion matrices before and after adjusting the BCT (Figs. 3D and 4D) indicate that in 50 random subsampling cross-validations, the average value of FN decreased from 2.84 to 0.36, and the average value of FP increased from 13.58 to 15.46. This means that after adjusting the BCT, the number of incorrect predictions for the positive class of the final model decreased by 87.32\(\%\), whereas the number of incorrect predictions for the negative class increased by only 13.84\(\%\).

BCT-adjusted model analysis. (A) Dynamic changes in model performance when adjusting BCT. (B) Prediction probability distribution of the BCT-adjusted model on the validation set. (C) Overall performance of the model after BCT adjustment. (D) Confusion matrix of 50-fold random subsampling cross validation applied to the BCT-adjusted model.

Model explanation

To ensure that the output results of the IDU prediction model were convincing, SHAP was used to explain the overall model. Figure 5A and B show the importance of each feature in the prediction process of the model, highlighting Cl as the key factor in predicting IDU. Other features, such as BHB and AG, also had a certain impact on the prediction results. Further analysis of the sample distribution of some important features (Fig. 5C–E) revealed that Cl had a relatively concentrated intragroup distribution and a clear boundary between groups; therefore, the model identified it as a key factor in IDU prediction. The intragroup distribution of BHB and AG was dispersed relative to Cl, but there was a clear boundary between groups, enabling effective differentiation between IDU and n-IDU. Figure 5F shows the IDU and n-IDU explanation force plots for all training samples. The horizontal axis represents each subject, and the vertical axis represents the importance of each feature to the prediction of each subject. Red and blue represent features that push subjects toward IDU and n-IDU, respectively. Figure 5G and H show the explanation force plots for subjects numbered 10 and 350 in Fig. 5F. The top features (such as Cl, BHB, AG, RBP, and aTPO) had a greater influence on the final prediction of the model and pushed the sample into one of the categories. In most cases, our prediction model strongly pushed the sample to IDU or n-IDU (as shown on the left and right sides of Fig. 5F), similar to Fig. 5G and H. When processing these samples, most features in the model yielded consistent binary classification results.

Global interpretation of the final model. (A) Feature importance calculated by SHAP. (B) Sample distribution beeswarm summary plot based on SHAP value. Each point corresponds to a subject, and the color of the point is the actual value of the point under the feature. (C–E) Scatter plot of some important features. Each point represents a patient, the horizontal axis is the actual value, and the vertical axis is the SHAP value. (F) Explanation force plot of the training sample. (G–H) Explanation force plot for a single subject.

In Fig. 6A–D, the IDU and n-IDU samples in the validation set were input into the prediction model and interpreted locally. The obtained results were similar to those of a previous global interpretation. Figure 6A and B show the model’s explanation of a single sample predicted as IDU. As shown in Fig. 6A, Cl, BHB, aTPO, CYSC, FT3, HCO3, FT4, FBG, and UA pushed it to IDU, and only a few features pushed it to n-IDU. Figure 6B intuitively shows the probability changes in the model when predicting the sample. The final model predicted it as IDU with a probability of 72.60\(\%\). Figure 6C and D show the model’s explanation of a single sample predicted as n-IDU. Among these, Cl, HCO3, RBP, UA, Folate, CYSC, aTPO, and FT4 pushed it to n-IDU. The final model predicted it as n-IDU with a probability of 94.25\(\%\).

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively analyzed the blood samples of IDU and n-IDU, revealing that some blood features are related to IDU. By studying and comparing the performance and stability of eight ML models, a prediction method for IDU was proposed. Since long-term IDU can impact the body, some blood indicators may become abnormal, and a single blood indicator is difficult to use to determine whether there is IDU, so there is a complex relationship between these abnormal blood indicators. ML can use the powerful computing power of computers to obtain the complex relationship between IDU and blood indicators from a large amount of sample data and establish a prediction model. Among the 8 ML models, LGB has the best performance on internal and external validation sets. LGB uses a histogram algorithm to divide continuous features into several intervals, and uses interval indexes instead of original values for calculation. This process discretizes continuous data, allowing LGB to adapt to hematological difference data sets and improve computational efficiency.

Our model used 13 blood indicators with simplified features to predict IDU, and after adjusting the BCT, it demonstrated good performance on the validation set. The final model achieved an accuracy, AUC, F1, sensitivity, and specificity of 86.5\(\%\), 0.930, 0.878, 0.994, and 0.742, respectively. Although the data set includes 80 blood indicators, the final model does not make IDU predictions based on all the indicators. This is due to the following reasons: First, only some of the blood indicators involved in the experiment are related to IDU predictions. If the model contains a large number of non-correlated features, it will affect its prediction effect; second, the increase in the number of blood indicators will lead to an exponential increase in the amount of model calculation, which will seriously affect the model training and prediction speed; third, a smaller number of blood indicators can reduce the economic and time costs of blood sampling and testing in practical applications, and improve the efficiency of IDU predictions.

Previous studies have used artificial intelligence methods to conduct predictive research on IDU. Daksha Yadav31 and Gnanasekar32 used deep learning methods to extract more obvious features such as blisters, ulcers, and muscle aging in facial images due to IDU, and established IDU prediction models, achieving 88.81\(\%\) and 84.68\(\%\) accuracy respectively.However, in most cases, such facial features only gradually appear after long-term or large-scale use of illicit drugs33. Our model can identify IDU without the help of visually recognizable features, but uses only the differecnes in some blood indicators between users and non-users to achieve IDU prediction, to identify those in the early stages of IDU.

To enhance the credibility of the model, we also use the SHAP method to explain the global and local aspects of the prediction model, so that the prediction results of the model have a certain factual basis.After analyzing the global and local explanations based on SHAP, we found interactions among the 13 features used to train the prediction model and conducted an in-depth study of the three most important features (Cl, BHB, and AG) in the prediction model.

Interaction analysis of blood characteristics. (A) Visualization of feature interactions between BHB and RBP. (B) RBP scatter plot. (C) Visualization of feature interactions between Cl and HCO3. (D) HCO3 scatter plot. (E) Visualization of feature interactions between AG and FT4. (F) FT4 scatter plot.

As shown in Fig. 7A, the interactive analysis of BHB and RBP features is shown. The positive SHAP values observed in the upper region of the plot indicate that the model identifies these samples as likely cases of substance use disorder. Most of these user sample points are blue or dark red, and from the color scale on the right side of Fig. 7A, it can be seen that the RBP of these sample points is around 30 ug/ml or below. At the same time, from Fig. 7B, it can be seen that the SHAP values of points with RBP around 30 ug/ml or below are all positive, indicating that the RBP in the blood is abnormal and is considered by the model to be an user. This means that in most cases, when the BHB content in the blood of the user is abnormal, the RBP content is also abnormal. Since RBP, BHB, and Folate are important indicators reflecting whether the liver is abnormal in the clinical diagnosis of liver disease34,35,36, it can be inferred that the model may make judgments on illegal drug use based on whether the liver is abnormal during detection.

In addition, as shown in Fig. 7C and D, the same phenomenon occurred for Cl and HCO3, both of which reflect human kidney function37,38. In Fig. 7C, the blue and dark red points represent all samples with abnormal HCO3. These sample points were concentrated in the upper-left corner of Fig. 7D and coincided with the abnormal Cl samples. They were all predicted by the model as IDU. As shown in Fig. 7E and F, AG, and FT4 reflected whether the human thyroid gland was abnormal39. The bright red points in Fig. 7E are abnormal FT4 points, some of which are concentrated in the upper-right corner, while others are scattered below. Compared to the first two groups, the interaction between AG and FT4 was not obvious because AG has a more considerable effect than FT4 in reflecting thyroid abnormalities39.

In general, the 13 features used to predict IDU can be divided into four categories: indicators reflecting the kidney (Cl, HCO3, UA, and CYSC), liver (RBP, BHB, Folate), and thyroid (AG, FT3, FT4, aTPO, and aTG), and indicators reflecting other organs (FGB). The interaction between these features manifests clinically as adverse effects of IDU on the kidney, liver, thyroid, and other organs (such as the pancreas)27,40,41,42,43. The combination of these clinical manifestations enables doctors to perform preliminary screening for IDU while performing organ-specific examinations in ordinary patients, which is of profound significance in clinical practice.

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully developed a prediction model for IDU that performed well on the internal and external validation sets and accurately predicted the vast majority of IDU sample inputs. Notably however, the study had some limitations.First, the sample size was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. A larger and more diverse sample would be necessary to validate the model’s robustness and applicability across different populations. Second, while the model used 13 blood features to predict IDU, there is a possibility that other important features were overlooked. The study’s feature selection process may have excluded relevant biomarkers that could improve the model’s accuracy.Finally, since the purpose of our development of this model is to conduct preliminary screening for illegal drug use, misjudgment is inevitable. We hope to find more illegal drug users in the preliminary screening, that is, higher TP, which may lead to a certain degree of increase in FP. After preliminary screening, more precise methods can be used to test subjects to reduce negative legal and economic consequences.

To our knowledge, this is the first method that is not limited to a single illicit drug and uses an ML model to predict IDU based on blood samples. This method has low requirements for sample timeliness and high confidence in predictions in most cases. Additionally, the model’s interpretability enhances its predictive reliability, making it an effective method for screening suspected IDUr. Future studies using larger and more diverse populations should be conducted to validate the model’s validity and generalizability. This will help to ensure that the model can be reliably applied in different population groups and clinical settings.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [IEEE DataPort] repository, [https://ieee-dataport.org/documents/hematological-tests-illicit-drug-user].

References

Whitley, P. et al. Analysis of urine drug test results from substance use disorder treatment practices and overdose mortality rates, 2013–2020. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2215425–e2215425. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15425 (2022).

Cheron, J. & Kerchove d’Exaerde, A. D. Drug addiction: from bench to bedside. Transl. Psychiatr. 11, 424. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01542-0 (2021).

Bates, J. N. et al. Post-operative order set decreases opioid prescriptions and increases efficiency. Am. Surg. 89, 539–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031348221148371 (2023).

Paz-Ramos, M. I., Cruz, S. L. & Violante-Soria, V. Amphetamine-type stimulants: novel insights into their actions and use patterns. Rev. Invest. Clin. 75, 143–157. https://doi.org/10.24875/ric.23000110 (2023).

Kendler, K. S., Ohlsson, H., Sundquist, K. & Sundquist, J. Drug abuse-associated mortality across the lifespan: a population-based longitudinal cohort and co-relative analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 52, 877–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1398-5 (2017).

Rockett, I. R., Putnam, S. L., Jia, H. & Smith, G. S. Declared and undeclared substance use among emergency department patients: a population-based study. Addiction 101, 706–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01397.x (2006).

Dragomir, L., Marina, V., Anghele, M., Anghele, A.-D. & Moscu, C. A. Incidence of intoxications in the emergency department of galati hospital with examples of cardiovascular effects of mdma intoxication. Diagnostics 13, 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13050940 (2023).

Farley, M. et al. A single method for 127 recommended and additional DUID drugs in blood and urine by LC-MS-MS. J. Anal. Toxicol. 46, 658–669. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkab075 (2022).

Zhuo, Y. et al. Simultaneous quantitative determination of amphetamines, opiates, ketamine, cocaine and metabolites in human hair: application to forensic cases of drug abuse. J. Forensic Sci. 65, 563–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.14179 (2020).

Tenore, P. L. Advanced urine toxicology testing. J. Addict. Dis. 29, 436–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2010.509277 (2010).

Nielsen, M. K. K., Johansen, S. S. & Linnet, K. Evaluation of poly-drug use in methadone-related fatalities using segmental hair analysis. Forensic Sci. Int. 248, 134–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.01.004 (2015).

Burch, H. J., Clarke, E. J., Hubbard, A. M. & Scott-Ham, M. Concentrations of drugs determined in blood samples collected from suspected drugged drivers in England and Wales. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 20, 278–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2012.10.005 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. A method for detecting and analyzing facial features of people with drug use disorders. Diagnostics 11, 1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11091562 (2021).

Simonovska, N. et al. Influence of duration of heroin dependence on humoral immunologic indicators. J. Addict. Med. 10, 448–452. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000259 (2016).

Guleken, Z. et al. Investigation of the discrimination and characterization of blood serum structure in patients with opioid use disorder using ir spectroscopy and pca-lda analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 190, 113553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113553 (2020).

Ciubotariu, D. et al. Experimental research showing the beneficial effect of oral zinc administration in opioid tolerance. Farmacia 63, 835–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-017-0995-1 (2015).

Ciubotariu, D., Ghiciuc, C. M. & Lupuşoru, C. E. Zinc involvement in opioid addiction and analgesia-should zinc supplementation be recommended for opioid-treated persons?. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy 10, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-015-0025-2 (2015).

Estevez, J. et al. Biochemical and haematological differentiation of opiate addicts from healthy subjects. A case control study. J. Appl. Biomed. 3, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.32725/jab.2005.004 (2005).

Hashemi, S. M., Bakhshipour, A. & Rafaiee, R. A comparison of blood indices in orally and inhaled opium addicts with non-addict healthy control. Zahedan J. Res. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.5812/zjrms-122931 (2023).

Demir, B., Sahin, S. K., Ozsoy, F., Altindag, A. & Elboga, G. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio in methamphetamine use disorder. Psychiatr. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 31, 34–39. https://doi.org/10.26226/morressier.597eedbed462b80296ca155e (2021).

Funchal, G. A. et al. Cocaine-use disorder and childhood maltreatment are associated with the activation of neutrophils and increased inflammation. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 36, 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2023.11 (2024).

Kaboudi, N. & Shayanfar, A. Predicting the drug clearance pathway with structural descriptors. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 47, 363–369 (2022).

Kaboudi, N. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ChatGPT for patients’ triage; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archiv. Acad. Emerg. Med. 12, e60 (2024).

Peng, Z. et al. A continuous late-onset sepsis prediction algorithm for preterm infants using multi-channel physiological signals from a patient monitor. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27, 550–561. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2022.3216055 (2022).

Yao, H. et al. A novel tropical geometry-based interpretable machine learning method: pilot application to delivery of advanced heart failure therapies. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27, 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2022.3211765 (2022).

Hu, J. et al. Identification and validation of an explainable prediction model of acute kidney injury with prognostic implications in critically ill children: a prospective multicenter cohort study. EClin. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102409 (2024).

Malhotra, S., Heptulla, R. A., Homel, P. & Motaghedi, R. Effect of marijuana use on thyroid function and autoimmunity. Thyroid 27, 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2016.0197 (2017).

Zou, Q., Xie, S., Lin, Z., Wu, M. & Ju, Y. Finding the best classification threshold in imbalanced classification. Big Data Res. 5, 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bdr.2015.12.001 (2016).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. nips’17: Proceedings of the 31st international conference on neural information processing systems. December 2017 [Cited 2021 Jul 20]. arxiv:1705.07874 (2017).

Kim, M. et al. Acute myocardial infarction prognosis prediction with reliable and interpretable artificial intelligence system. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 31, 1540–1550. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocae114 (2024).

Yadav, D. et al. Effect of illicit drug abuse on face recognition. in 2016 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1109/WACV.2016.7477556 (IEEE, 2016).

Gnanasekar, S. T. & Yanushkevich, S. Face attributes and detection of drug addicts. in 2019 Eighth International Conference on Emerging Security Technologies (EST), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/EST.2019.8806203 (IEEE, 2019).

Pandey, P., Singh, R. & Vatsa, M. Face recognition using scattering wavelet under illicit drug abuse variations. In 2016 International Conference on Biometrics (ICB), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICB.2016.7550091 (IEEE, 2016).

Li, K., Wang, W.-H., Wu, J.-B. & Xiao, W.-H. B-hydroxybutyrate: a crucial therapeutic target for diverse liver diseases. Biomed Pharmacother 165, 115191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115191 (2023).

Alapatt, P. et al. Liver retinol transporter and receptor for serum retinol-binding protein (rbp4). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 1250–1265. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m112.369132 (2013).

Christensen, K. E. et al. High folic acid consumption leads to pseudo-MTHFR deficiency, altered lipid metabolism, and liver injury in mice. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 101, 646–658. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.086603 (2015).

McCallum, L. et al. Serum chloride is an independent predictor of mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension 62, 836–843. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01793 (2013).

Driver, T. H. et al. Low serum bicarbonate and kidney function decline: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (mesa). Am. J. Kidney Dis. 64, 534–541. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.05.008 (2014).

Liang, H., Wang, J.-M., Wei, X.-Q., Su, X.-Q. & Zhang, B.-X. Thyroid function, renal function, and depression: an association study. Front. Psychol. 14, 1182657. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1182657 (2023).

Degenhardt, L. et al. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Psychiatr. 5, 987–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7 (2018).

Bundy, J. D. et al. Self-reported tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use and progression of chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 993–1001. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.11121017 (2018).

Pastor, A., Conn, J., MacIsaac, R. J. & Bonomo, Y. Alcohol and illicit drug use in people with diabetes. Lancet Diabet. Endocrinol. 8, 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(19)30410-3 (2020).

Roy, D. N. & Goswami, R. Drugs of abuse and addiction: a slippery slope toward liver injury. Chem. Biol. Interact. 255, 92–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2015.09.018 (2016).

Funding

This work was supported in part by Yunnan Technological Innovation Center of Drug Addiction Medicine (202305AK340001), Yunnan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (approval number 2021.L.2), and all participants provided written informed consent after they were informed of the purposes, processes, and potential risks associated with the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, A., Shen, Y., Xu, Y. et al. Explainable illicit drug abuse prediction using hematological differences. Sci Rep 15, 28892 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06154-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06154-y