Abstract

Urban populations, coupled with increased healthcare service usage, highlight the need for safe and sustainable medical waste management (MWM). Choosing the right technology for MWM is a crucial challenge for decision-makers aiming to protect public health. Multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) techniques are often used to address uncertainty and complexity inherent in such decisions. MCDM techniques based on traditional fuzzy sets (such as spherical and t-spherical fuzzy sets) leave significant membership value. In this response, a f, g, h-fractional fuzzy set (f, g, h-FrFS) based MCDM model is introduced. This study introduces the f, g, h-FrFS based Hamming and normalized Hamming distances. Additionally, we propose an improved Criteria Importance through Inter-Criteria Correlation (CRITIC) method to assess criteria weights and a novel distance-based Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) method to evaluate and rank MWM technologies. To test the robustness of the proposed approach, a sensitivity analysis is conducted, demonstrating the stability of the model under varying conditions. The result is the development of a comprehensive MCDM framework, referred to as f, g, h-FrF-CRITIC-TOPSIS, which incorporates relevant criteria for evaluating MWM technologies. The effectiveness of this framework is further validated through a comparative study. The results align with the actual situation and offer valuable insights into the implementation of suitable treatment technologies for MWM. This methodology proves to be highly effective in addressing the complex decision-making challenges associated with MWM, particularly in uncertain environments. Ultimately, this technique offers significant value for policymakers and organizations involved in medical systems. In medical premises, MWM is complicated, so this tool can assist them in navigating the complexities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Proper disposing of medical waste is critical in medical facilities, safeguarding public health and safety. Medical waste management involves the efficient administration, collection, transportation, processing, and disposal of hazardous materials produced in healthcare settings, research centers, and laboratories. In partnership with the World Health Organization (WHO), the National Health Insurance (NHI) will assess the technologies employed to manage medical waste in these environments. This study aims to closely examine the handling and disposal techniques of healthcare waste in these institutions, ensuring that stringent guidelines are met. The global COVID-19 pandemic has led to a significant surge in medical waste production. Most of this waste, produced in medical facilities, poses a serious threat due to the varying levels of harmful compounds it contains. Studies by Rume1 and Padmanabhan2 emphasize the importance of proper management of this type of waste to mitigate its harmful effects on public health, the environment, and all living species.

The foundation of medical waste management (MWM) lies in processing technology, which determines how healthcare waste (HCW) is processed and decomposed. Hospitals and healthcare facilities rely on specific suppliers for medical waste treatment and disposal, with several options often available. For healthcare facility executives, selecting the most suitable treatment solution involves a thorough evaluation process, where various factors related to the treatment technology must be considered. These include factors such as the type of waste, loading capacity, technical reliability, environmental emissions, health and safety concerns, as well as the reduction in waste mass and volume3. Consequently, choosing the right HCW treatment can be viewed as a complex multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) problem. To address this, suitable MCDM methods can be applied to identify the most effective treatment technology for MWM4,5,6. Real-life situations are often complex, and decision-making techniques are essential to deal with them. MCDM methodologies are particularly useful in these circumstances. According to Darici et al.7, technological projections in the AI age can be justified by ambiguous interactions of MCDM.

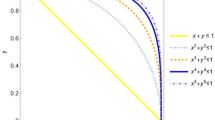

Today, Managing complex problems requires the ability to make well-informed decisions. In fields like engineering, agriculture, economics, and industrial production, data uncertainty is a significant challenge. This issue has been addressed by several researchers8,9,10,11. Accurate data collection is often hindered by challenges such as missing information, privacy concerns, or complex data. These challenges can be addressed through fuzzy number extensions. In 1965, Zadeh introduced the concept of fuzzy sets (FS) to represent vague, uncertain, and imprecise information12. In this framework, an element is assigned a membership degree (MB) that determines whether it belongs to a particular set. These degrees range from 0 to 1, offering a flexible and precise way to handle uncertain or vague data. However, FS does not account for non-membership degrees (NMB). To address this limitation, Atanassov introduced the concept of intuitionistic fuzzy sets (IFS) in 198613. Unlike FS, IFS considers both MB and NMB when making decisions. In certain cases, a decision maker might encounter situations where the squares of MB and NMB are less than or equal to 1, but their sum exceeds 1. To resolve this mathematical issue, Yager introduced the Pythagorean fuzzy set (PFS) in 201314. The PFS model offers a more sophisticated approach, considering MB and NMB in a more nuanced manner to handle these situations. In multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM), PFS has been widely recognized as one of the best tools for managing and describing ambiguity. However, PFS still has limitations, particularly in handling indeterminacy degrees (ID). To address this gap, Gundogdu15 proposed the concept of a spherical fuzzy set (SFS). The decision-making process in SFS is more flexible than in PFS, allowing for better handling of uncertain situations. Building on this, Mahmood et al.16 introduced t-spherical fuzzy sets (t-SFS), which are considered one of the most comprehensive types of fuzzy systems. Garg17 explored the relationship between t-SFS, their associated aggregation operators, and the operational laws governing t-SFS. Notably, in t-SFS, there is no distinction in the power levels of MB, ID, and NMB.

The previous analysis shows that the research conducted in this area utilizes different powers to control membership levels. For example, in SF frameworks, decision-makers apply a power of 2 to the membership function, while in t-SF frameworks, a power of t is used. By employing these distinct powers, decision-makers regulate the impact of membership tiers based on the strategies they adopt to address varying degrees of ambiguity and uncertainty. In some real-world scenarios, a decision-maker may feel confident in a particular strategy and assign it a score of 1 when evaluating that strategy. However, existing models may not easily accommodate such evaluations, particularly when the set representation is \(D = (d, 1, 0.25, 0.8)\) where \(d \in D\). To address this limitation, Gulistan et al. (2024) introduced the concept of p, q, r-fractional fuzzy sets18. This new model improves the functionality and flexibility of traditional fuzzy sets, enabling the visualization and handling of information that conventional fuzzy models cannot adequately represent. The MCDM methods, when applied within conventional fuzzy sets, overlook the maximum value inherent in experts’ judgments. Therefore, this study aims to enhance MCDM models within the f, g, h-FrFNs environment.

An accurate and reliable ranking of alternatives in MCDM depends on a proper weighting of the criteria. Since not all criteria are equally critical in every MCDM problem, it’s crucial to determine the weight of each criterion to reflect its significance. There are various methods available for calculating subjective and objective weights in MCDM scenarios. One such approach is the Intercriteria Correlation Technique (CRITIC), developed by Diakoulaki et al. (1995)19. This method computes weights based on correlation coefficients between criteria. The CRITIC model is a versatile MCDM approach tailored to address complex decision-making scenarios including multiple criteria. Ke et al.20 presented a novel combined weighting method integrating the best worst method and the CRITIC based on an IFSs for urban integrated energy system plan selection. Han and Rani21 proposed a novel CRITIC approach based on Pythagorean fuzzy sets to evaluate the barriers of the blockchain technology adoption in supply chain management. Wang et al.22 analyzed and rank the barriers to resilient supply chain adoption in the food industry. Over the years, the CRITIC model has been extensively explored and applied in various studies (Table 1).

The Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) is a widely adopted method pioneered by Hwang and Yoon34 to address Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) problems in various fields35,36,37,38. This approach is commonly used to rank alternatives, offering a more thorough comparison than other decision-making methods. At its core, TOPSIS revolves around identifying positive and negative ideal solutions39. The ranking of alternatives is accomplished by calculating their relative closeness to the ideal solution40. Specifically, when an ideal solution becomes farther away from the negative ideal solution, it gets closer to the positive ideal solution41. In this study, TOPSIS is applied to evaluate and rank medical waste management technologies based on their performance in a fractional fuzzy environment. Table 2 summarizes the research conducted based on the TOPSIS method.

Medical waste is categorized into hazardous and non-hazardous categories based on its inherent properties. It is inherently dangerous as it may contain flammable, toxic, radioactive, oxidized, or poisonous substances. Mishandling such waste poses serious risks to human health and the environment. MCDM methodologies for hazardous waste, including medical waste, have been extensively investigated. Hsu et al.55 proposed an analytical hierarchy process (AHP)-based technique for selecting infectious medical waste disposal firms, utilizing expert interviews to mitigate subjective bias. Ozkan56 analyzed medical waste management practices in Turkey and proposed two treatment option selection methods. Aung et al.57 evaluated medical waste management practices across eight hospitals in Myanmar using AHP. Yazdani et al.58 integrated the BWM with interval rough numbers to optimize medical waste disposal location selection. Jangre et al.59 identified and prioritized 18 factors influencing business practices in MWM through BWM. Further studies are outlined in Table 3.

Research gaps and motivations

The grading of MB, ID, and NMB has been applied in a number of previous studies, including SFS15 and t-SFS16. However, these models face certain limitations when dealing with grade-related constraints. For instance, they struggle to compute maximum values, such as those equal to 1. As an example, take a set with the description \(D = (d, \langle 1.0, 0.65, 0.55\rangle , d \in D )\). Clearly, these models cannot handle this type of information adequately. Because SFSs can only accommodate datasets if the square sum of MB \((\mathfrak {p})\), ID \((\mathfrak {z})\), and NMB \((\mathfrak {j})\) is equal to or less than 1 \((\mathfrak {p}^2 + \mathfrak {z}^2 + \mathfrak {j}^2 \le 1)\). Additionally, t-SFSs can only accommodate datasets if the t-th power sum of \(\mathfrak {p}\), \(\mathfrak {z}\), and \(\mathfrak {j}\) is equal to or less than 1 \((\mathfrak {p}^t + \mathfrak {z}^t + \mathfrak {j}^t \le 1)\). Due to the limitations of existing fuzzy set structures such as SFS and t-spherical sets, Gulistan et al. presented the p, q, r-fractional fuzzy set framework18. Besides providing enhanced flexibility and versatility, this structure is capable of displaying and manipulating information that is not adequately accommodated by traditional fuzzy sets. Complex data can be handled nuancedly by using parameters p, q, and r in this approach. In recent research, advanced MCDM methodologies such as CRITIC72, AHP73, and TOPSIS74 have been utilized for evaluating MWM. However, these techniques are often applied independently or within constrained hybrid frameworks. A more refined approach that integrates these methodologies with advanced fuzzy logic techniques is required to effectively address complex decision-making challenges. Existing methodologies frequently lack the adaptability necessary to tackle these emerging issues, particularly within the domain of MWM.

The CRITIC and TOPSIS methods, when based on conventional fuzzy sets, fail to account for the maximum value embedded in experts’ judgments25,32. To address this limitation, it is essential to develop a robust CRITIC method for determining criteria weights and a TOPSIS method for ranking alternatives. This method will effectively handles the maximum judgments provided by experts. This proposed model seeks to deliver a more robust, flexible, and accurate approach to evaluating MWM, addressing existing gaps and contributing significantly to MWM decision-making. The study underscores the inadequacy of current MWM assessment methods. It notes that despite extensive research into various assessment techniques, there remains a notable absence of integration with advanced fuzzy sets principles, particularly fractional fuzzy sets. To improve MWM evaluation accuracy and depth, this study introduces a hybrid methodology that combines CRITIC and TOPSIS methods. This innovative approach addresses a critical gap in the literature by providing a more robust framework for assessing MWM viability. The study is driven by the urgent need for more reliable and efficient decision-making methodologies in MWM evaluation.

Contributions

Real-world problems are increasingly capturing the attention and efforts of DMs, who are developing realistic strategies to address them. As the situations grow more complex, DMs operating within the adaptive decision-making paradigm face significant difficulty identifying optimal responses. This study will help overcome numerous obstacles by providing practical and sustainable solutions to these real-life challenges. This research addresses the identified gaps in existing literature:

-

To address the MWM problem, an MCDM framework is developed and applied within a f, g, h-FrFN environment.

-

A numerical application of MCDM is utilized to identify optimal MWM strategies, validating the proposed method.

-

f, g, h-FrFSs based Hamming distances and normalized Hamminig distances are introduced.

-

An extension of the CRITIC model is introduced in this research to compute criteria weights using f, g, h-FrFNs in the MCDM dilemma.

-

To enhance the MCDM methodology for f, g, h-FrFNs, we have introduced an improved f, g, h-FrFN-based TOPSIS model.

-

Sensitivity and comparative analyses are conducted with benchmark methodologies to assess the robustness of the developed approach.

Preliminaries

Several fuzzy sets are discussed in this section, including IFS, PFS, SFS, T-SFS, and f, g, h-fractional fuzzy sets. To successfully implement the proposed integrated methodology, these important concepts are crucial.

Intuitionistic fuzzy set

Consider \(\mathfrak {N}\) be a finite non-empty set. An IFS13 \(\mathfrak {K}\) over \(\mathfrak {N}\) has the following definition:

where \(\varphi _\mathfrak {K}(\mathfrak {n})\) and \(\sigma _\mathfrak {K}(\mathfrak {n})\) represent the MB and NMB of \(\mathfrak {K}\) respectively, such that \(\varphi _\mathfrak {K}(\mathfrak {n}), \sigma _\mathfrak {K}(\mathfrak {n}) \in [0, 1]\) and \(\varphi _\mathfrak {K}(\mathfrak {n}) + \sigma _\mathfrak {K}(\mathfrak {n}) \preceq 1\).

Pythagorean fuzzy set

Consider \(\mathfrak {N}\) be a finite non-empty set. A PFS14 \(\mathfrak {G}\) over \(\mathfrak {N}\) has the following definition:

where \(\varphi _\mathfrak {G}(\mathfrak {n})\) and \(\sigma _\mathfrak {G}(\mathfrak {n})\) represent the MB and NMB of \(\mathfrak {G}\) respectively, such that \(\varphi _\mathfrak {G}(\mathfrak {n}), \sigma _\mathfrak {G}(\mathfrak {n}) \in [0, 1]\) and \((\varphi _\mathfrak {G}(\mathfrak {n}))^2 + (\sigma _\mathfrak {G}(\mathfrak {n}))^2 \preceq 1\).

Spherical fuzzy set

For any universal set \(\mathscr {N}\), a Spherical Fuzzy Set (SFS)15 H can be expressed as:

Here, \({\varphi }_{H}(\mathfrak {n})\) represents membership grade, \({\varpi }_{H}(\mathfrak {n})\) represents neutral membership grade, and \({\sigma }_{H}(\mathfrak {n})\) represents non-membership grade of \(\mathfrak {n}\) in element \(\mathfrak {n} \in \mathscr {N}\) such that \(0 \le {\varphi }_{H}(\mathfrak {n}), {\varpi }_{H}(\mathfrak {n}), {\sigma }_{H}(\mathfrak {n}) \le 1\) and \(({\varphi }_{H}(\mathfrak {n}))^2 + ({\varpi }_{H}(\mathfrak {n}))^2 + ({\sigma }_{H}(\mathfrak {n}))^2 \le 1\).

t-Spherical fuzzy set

For any universal set \(\mathscr {N}\), a t-Spherical Fuzzy Set (t-SFS)16 T can be expressed as:

In this context, \({\varphi }_{T}(\mathfrak {n})\) represents membership grade, \({\varpi }_{T}(\mathfrak {n})\) represents neutral membership grade, and \({\sigma }_{T}(\mathfrak {n})\) represents non-membership grade of \(\mathfrak {n}\) in element \(\mathfrak {n} \in \mathscr {N}\) such that \(0 \le {\varphi }_{T}(\mathfrak {n}), {\varpi }_{T}(\mathfrak {n}), {\sigma }_{T}(\mathfrak {n}) \le 1\) and \(({\varphi }_{T}(\mathfrak {n}))^t + ({\varpi }_{T}(\mathfrak {n}))^t + ({\sigma }_{T}(\mathfrak {n}))^t \le 1\).

f, g, h-Fractional fuzzy set

For any finite set \(\mathscr {N}\), a f, g, h-Fractional fuzzy set (f, g, h-FrFS)18 \({\widetilde{S}}\) over an element \(\mathfrak {n} \in \mathscr {N}\) can be expressed as:

In this context, \({\varphi }_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {n}) \in [0, 1]\) represents membership grade, \({\varpi }_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {n}) \in [0, 1]\) represents impartial membership grade, while \({\sigma }_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {n}) \in [0, 1]\) represents non-membership grade of a component \(\mathfrak {n} \in \mathscr {N}\) satisfying the condition \(\frac{1}{f}({\varphi }_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {n})) + \frac{1}{h}({\varpi }_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {n})) + \frac{1}{g}({\sigma }_{\widetilde{S}}(\mathfrak {n})) \le 1\), here f and g are positive integers such that \(f, g \ge 1\), and \(h = {LCM}(f, g)\).

The triplet \(({\varphi }, {\varpi }, {\sigma })\) satisfying the condition \(\frac{1}{f}({\varphi }) + \frac{1}{h}({\varpi }) + \frac{1}{g}({\sigma }) \le 1\) is referred to as a f, g, h-FrFN, here \(f, g \ge 2\) and \(h = {LCM}(f, g)\).

For any f, g, h-FrFNs \({\widetilde{S}}\), the score function of \({\widetilde{S}}\) can be expressed as:

The accuracy function of f, g, h-FrFN \({\widetilde{S}}\) is as follows:

Fundamental arithmetic operations can be defined as follows, let \(\tilde{O} = ({\varphi }_{\tilde{O}}, {\varpi }_{\tilde{O}}, {\sigma }_{\tilde{O}})\) and \(\tilde{V} = ({\varphi }_{\tilde{V}}, {\varpi }_{\tilde{V}}, {\sigma }_{\tilde{V}})\) then:

-

Addition Operation

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} \tilde{O} \oplus \tilde{V} = \left( \frac{1}{f}{\varphi }_{\tilde{O}} + \frac{1}{f}{\varphi }_{\tilde{V}} - \frac{1}{f}({\varphi }_{\tilde{O}})({\varphi }_{\tilde{V}}), \frac{1}{h}({\varpi }_{\tilde{O}})({\varpi }_{\tilde{V}}), \frac{1}{g}({\sigma }_{\tilde{O}})({\sigma }_{\tilde{V}}) \right) \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(8) -

Multiplication Operation

$$\begin{aligned} \tilde{O} \otimes \tilde{V} = \left( \frac{1}{f}({\varphi }_{\tilde{O}})({\varphi }_{\tilde{V}}), \frac{1}{h}{\varpi }_{\tilde{O}} + \frac{1}{h}{\varpi }_{\tilde{V}} - \frac{1}{h}({\varpi }_{\tilde{O}})({\varpi }_{\tilde{V}}), \frac{1}{g}{\sigma }_{\tilde{O}} + \frac{1}{g}{\sigma }_{\tilde{V}} - \frac{1}{g}({\sigma }_{\tilde{O}})({\sigma }_{\tilde{V}}) \right) \end{aligned}$$(9) -

Multiplication by a scalar number \(\lambda > 0\)

$$\begin{aligned} \lambda \cdot \tilde{O} = \left( \frac{1}{f}({\varphi }_{\tilde{O}})^\lambda , \frac{1}{h}({\varpi }_{\tilde{O}})^\lambda , 1 - \left( 1 - \frac{1}{g}{\sigma }_{\tilde{O}}\right) ^\lambda \right) \end{aligned}$$(10) -

Scalar power \(\lambda > 0\)

$$\begin{aligned} \tilde{O}^\lambda = \left( 1 - \left( 1 - \frac{1}{f}{\varphi }_{\tilde{O}}\right) ^\lambda , 1 - \left( 1 - \frac{1}{h}{\varpi }_{\tilde{O}}\right) ^\lambda , \frac{1}{g}({\sigma }_{\tilde{O}})^\lambda \right) \end{aligned}$$(11)

f, g, h-fractional fuzzy weighted averaging operator

Assume that \({\widetilde{Q}}_1, {\widetilde{Q}}_2, \ldots , {\widetilde{Q}}_n\) is a group of f, g, h-FrFNs. Consider \({\xi _y} = (\xi _1, \xi _2, \ldots , \xi _n)\) be the weights for these f, g, h-FrFNs, where each \({\xi _y} \in [0, 1]\), and \(\sum {\xi _y} = 1\) for all \(y = 1, 2, \ldots , n\). Mapping of f, g, h-fractional fuzzy weighted averaging (f, g, h-FrFWA) operator18 is \({f, g, h}-{FrFWA}: \triangle ^n \rightarrow \triangle\) and can be described as:

f, g, h-fractional fuzzy weighted geometric operator

Consider that \({\widetilde{Q}}_1, {\widetilde{Q}}_2, \ldots , {\widetilde{Q}}_n\) is a group of f, g, h-FrFNs. Consider \({\xi _y} = (\xi _1, \xi _2, \ldots , \xi _n)\) be the weights for these f, g, h-FrFNs, where each \({\xi _y} \in [0, 1]\), and \(\sum {\xi _y} = 1\) for all \(y = 1, 2, \ldots , n\). Mapping of f, g, h-fractional fuzzy weighted geometric (f, g, h-FrFWG) operator18 is \({f, g, h}-{FrFWG}: \triangle ^n \rightarrow \triangle\) and can be described as:

Distance measures between f, g, h-fractional fuzzy sets

The hamming distance and normalized hamming distance are defined in this section.

Definition 1

Let \(\mathfrak {E} : \text {FrFS}^{fgh} \times \text {FrFS}^{fgh} \rightarrow [0, 1]\) is a real-valued function, it must satisfy the following axioms:

-

(\(D_1\)) \(0 \le \mathfrak {E}(\P _1, \P _2) \le 1 \quad \forall \, \P _1, \P _2 \in \text {FrFS}^{fgh}\),

-

(\(D_2\)) \(\mathfrak {E}(\P _1, \P _2) = 0\) if and only if \(\P _1 = \P _2\),

-

(\(D_3\)) \(\mathfrak {E}(\P _1, \P _2) = \mathfrak {E}(\P _2, \P _1)\),

-

(\(D_4\)) \(\P _1 \subseteq \P _2 \subseteq \P _3\) if and only if \(\mathfrak {E}(\P _1, \P _3) \ge \mathfrak {E}(\P _1, \P _2)\) and \(\mathfrak {E}(\P _1, \P _3) \ge \mathfrak {E}(\P _2, \P _3)\).

Definition 2

Let \(\P _1\) and \(\P _2\) be two same-type f, g, h-FrFSs. Then, the Hamming distance represented by \(\mathfrak {E}_{HM}\) between f, g, h-FrFSs \(\P _1\) and \(\P _2\) can be expressed as shown below:

Proposition 1

Let \(\P _1\) and \(\P _2\) be two \(f, g, h\)-FrFSs. Then, the Hamming distance \(\mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2)\) meets the following characteristics:

-

(\(P_1\)) \(0 \le \mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2) \le 1, \quad \forall \quad \P _1, \P _2 \in \text {FrFS}^{fgh}\).

-

(\(P_2\)) \(\mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2) = 0\) if and only if \(\P _1 = \P _2\).

-

(\(P_3\)) \(\mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2) = \mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _2, \P _1)\).

-

(\(P_4\)) If \(\P _1 \subseteq \P _2 \subseteq \P _3\), then \(\mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _3) \ge \mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2) \quad \text {and} \quad \mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _3) \ge \mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _2, \P _3).\)

Proof

Let \(\P _1\) and \(\P _2\) be two f, g, h-FrFSs. We prove the following:

(\(P_1\)) Since \(\P _1\) and \(\P _2\) are f, g, h-FrFSs, then

Therefore,

Hence, \(0 \le \mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2).\) Further, we have:

Then,

Therefore, \(\mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2) \le 1,\) which implies that \(0 \le \mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2) \le 1.\)

(\(P_2\)) Let \(\mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2) = 0\) if and only if

This implies \(\frac{1}{f}\varphi _1 = \frac{1}{f}\varphi _2, \quad \frac{1}{h}\varpi _1 = \frac{1}{h}\varpi _2, \quad \frac{1}{g}\sigma _1 = \frac{1}{g}\sigma _2\) Therefore, \(\P _1 = \P _2\).

(\(P_3\)) We have

Thus, \(\mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2) = \mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _2, \P _1).\)

(\(P_4\)) We have

Since \(\P _1 \subseteq \P _2 \subseteq \P _3\), we have \(\varphi _1 \preceq \varphi _2 \preceq \varphi _3\), \(\varpi _1 \preceq \varpi _2 \preceq \varpi _3\), and \(\sigma _1 \succeq \sigma _2 \succeq \sigma _3\).

It is easy to show that:

Thus,

Similarly,

And for \(\frac{1}{g}\sigma\),

Thus,

Therefore,

Thus, \(\mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _2) \le \mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _3).\)

By a similar argument, we also have \(\mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _2, \P _3) \le \mathfrak {E}_{HM}(\P _1, \P _3).\) \(\square\)

Definition 3

Let \(\P _1\) and \(\P _2\) be two same-type f, g, h-FrFSs. We will assume \(\mathscr {Q} = \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2,...,\alpha _n\}\) unless otherwise stated. Then, the normalized Hamming distance represented by \(\mathfrak {E}_{NHM}\) between f, g, h-FrFSs \(\P _1\) and \(\P _2\) can be expressed as shown below:

Proposition 2

Let \(\P _1\) and \(\P _2\) be two \(f, g, h\)-FrFSs. Then, the normalized Hamming distance \(\mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2)\) meets the following characteristics:

-

(\(P_1\)) \(0 \le \mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2) \le 1, \quad \forall \quad \P _1, \P _2 \in \text {FrFS}^{fgh}\).

-

(\(P_2\)) \(\mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2) = 0\) if and only if \(\P _1 = \P _2\).

-

(\(P_3\)) \(\mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2) = \mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _2, \P _1)\).

-

(\(P_4\)) If \(\P _1 \subseteq \P _2 \subseteq \P _3\), then \(\mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _3) \ge \mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2) \quad \text {and} \quad \mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _3) \ge \mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _2, \P _3).\)

Proof

Let \(\P _1\) and \(\P _2\) be two f, g, h-FrFSs. We prove the following:

(\(P_1\)) Since \(\P _1\) and \(\P _2\) are f, g, h-FrFSs, then

Therefore,

Hence, \(0 \le \mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2).\) Further, we have:

Then,

Therefore, \(\mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2) \le 1,\) which implies that \(0 \le \mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2) \le 1.\)

(\(P_2\)) Let \(\mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2) = 0\) if and only if

\(\Longleftrightarrow \frac{1}{f}\varphi _1(\alpha _i) = \frac{1}{f}\varphi _2(\alpha _i), \quad \frac{1}{h}\varpi _1(\alpha _i) = \frac{1}{h}\varpi _2(\alpha _i), \quad \frac{1}{g}\sigma _1(\alpha _i) = \frac{1}{g}\sigma _2(\alpha _i) \quad \text {for} \quad i = 1, 2, \dots , n.\)

Therefore, \(\P _1 = \P _2\).

(\(P_3\)) We have

Thus, \(\mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2) = \mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _2, \P _1).\)

(\(P_4\)) We have

Since \(\P _1 \subseteq \P _2 \subseteq \P _3\), we have \(\varphi _1 \preceq \varphi _2 \preceq \varphi _3\), \(\varpi _1 \preceq \varpi _2 \preceq \varpi _3\), and \(\sigma _1 \succeq \sigma _2 \succeq \sigma _3\), \(\quad \forall \quad \alpha \in \mathscr {Q}\).

It is easy to show that:

Thus,

Thus,

for \(i = 1, 2,\dots ,n\) and

Thus, \(\mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _2) \le \mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _3).\)

By a similar argument, we also have \(\mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _2, \P _3) \le \mathfrak {E}_{NHM}(\P _1, \P _3).\) \(\square\)

Decision-making methods under f, g, h-fractional fuzzy framework

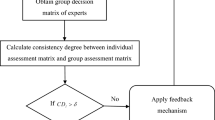

This section introduces the concept of the f, g, h-fractional fuzzy CRITIC method. In addition, we introduced the f, g, h-fractional fuzzy TOPSIS method. Our goal is to establish an integrated f, g, h-FrF CRITIC-TOPSIS algorithm that dynamically determines criteria weights and performs robust alternatives assessments to enhance MCDM evaluation accuracy. Figure 1 illustrates the systematic methodology of the proposed study.

f, g, h-Fractional fuzzy CRITIC

In this study, the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC method is developed to evaluate the importance of criteria and their weights. As a result of incorporating real-time scenarios and expert opinions, this method is highly effective for calculating criteria weights. According to f, g, h-FrF CRITIC, the steps are as follows:

Step 1: Experts are assessed and their credibility is determined. Experts are categorized based on qualifications and experience using Table 4. Expert weights are calculated using Eq.16. Considering the number of experts and \(E_c = (\varphi _c, \varpi _c, \sigma _c)\) as the associated FrFN, the weight of each expert is determined by their knowledge and experience.

Step 2: Gather information from a group of decision makers about alternatives based on the significance of the criteria. The linguistic variables used to assess the alternatives in terms of FrFNs are shown in Table 5. The assessment values presented by the decision experts can be systematically structured as Eq. 17:

Each of these matrices reflects the assessment data, where \(\mathfrak {W}^{(c)}_{kl}\) corresponds to the assessment value provided by the \(c\)-th decision expert (\(c = 1, 2, \dots , s\)) for the \(k\)-th strategy (\(k = 1, 2, \dots , m\)) with respect to the \(l\)-th criteria (\(l = 1, 2, \dots , n\)) under the f, g, h-FrF framework.

Step 3: A f, g, h-FrF combined decision matrix is generated by aggregating individual expert assessments. Experts with higher weights are likely to have an important impact on the final outcome of this process. Each criterion is evaluated by aggregating all experts’ evaluations using Eq. 18 and aggregated matrix represented as Eq. 19.

For criterion l, \(z_l\) represents the aggregated value.

Step 4: Calculate decision score matrix using Eq. 20.

Step 5: Most attribute sets contain of two categories, namely benefit element and cost element, respectively termed BE and CE. There is no need to normalize decision attributes if all the attributes are BE or CE. A conversion of CE ratings into BE is executed in MCDM when there are BE and CE evaluations. Utilize Eq. 21 to convert all the inputs into a f, g, h-FrF decision matrix.

where \(\mathfrak {W}_{l}^{-} = \min \mathfrak {W}_{kl}\) and \(\mathfrak {W}_{l}^{+} = \max \mathfrak {W}_{kl}\).

Step 6: Calculate the correlation coefficient using Eq. 22 and it indicates how closely one criterion is related to another. When two criteria are compared, “1” signifies a positive nexus, and “-1” signifies a negative nexus. The correlation coefficients between all the criteria are calculated as follows:

where \(\overline{\mathfrak {V}_l} = \frac{\sum _{k=1}^{m}\mathfrak {V}_{kl}}{m}\) and \(\overline{\mathfrak {V}_o} = \frac{\sum _{k=1}^{m}\mathfrak {V}_{ko}}{m}\)

Step 7: Compute the standard deviation using Eq. 23.

Step 8: The information index is computed using Eq. 24.

Step 9: Calculate the weights using Eq. 25

f, g, h-Fractional fuzzy TOPSIS

Extension of TOPSIS with f, g, h-FrFS is presented here:

Step 10: Gather information from a group of decision makers about alternatives based on the significance of the criteria. The linguistic variables used to assess the alternatives in terms of FrFNs are shown in Table 5. The assessment values presented by the decision experts can be systematically structured as Eq. 26:

Each of these matrices reflects the assessment data, where \(\mathfrak {W}^{(c)}_{kl}\) corresponds to the assessment value provided by the \(c\)-th decision expert (\(c = 1, 2, \dots , s\)) for the \(k\)-th strategy (\(k = 1, 2, \dots , m\)) with respect to the \(l\)-th criteria (\(l = 1, 2, \dots , n\)) under the f, g, h-FrF framework.

Step 11: A f, g, h-FrF integrated decision matrix is generated by aggregating individual expert assessments. Experts with higher weights are likely to have an important impact on the final outcome of this process. Each criterion is evaluated by aggregating all experts’ evaluations using Eq. 27 and aggregated matrix represented as Eq. 28.

For criterion l, \(z_l\) represents the aggregated value.

Step 12: A f, g, h-FrF aggregated decision matrix is generated by applying Eq. 29 to Eq. 28 and the aggregated matrix is represented as Eq. 30.

For criterion l, \(t_l\) represents the aggregated value.

Step 13: f, g, h-FrF Positive and f, g, h-FrF Negative Ideal Solutions are determined (PI and NI) for the aggregated decision matrix \((\mathscr {T}^{ag})\):

Step 14: The normalized Hamming distances from f, g, h-FrF-PIS and f, g, h-FrF-NIS are computed for each alternative:

Step 15: A closeness coefficient is computed for each alternative:

Step 16: Arrange the technologies in descending order to select the best option.

Application of the proposed CRITIC-TOPSIS model in medical waste management

This section analyzes the optimal health care waste treatment technology based on the presented model. We develop a problem analysis and then discuss criteria and solutions. The model is then employed as a tool for determining a solution. The final step involves sensitivity analysis and comparison.

Description of MWM technologies

The management of medical waste is essential to the smooth operation of healthcare, laboratories, and research facilities. This process involves the careful and responsible disposal of waste materials generated in these environments. Public health, the environment, and the well-being of those who work in healthcare and waste disposal are more important than following regulations. Managing medical waste correctly prevents infections, conserves natural resources, and ensures a healthier work environment for all. Following are some techniques and strategies important to the management of medical waste:

Steam sterilization

Sterilization is a vital technique in medical waste management, particularly for safely handling potentially infectious and hazardous materials generated in hospitals, research centers, and similar institutions. This process plays a key role in ensuring that BMW is rendered safe before its final disposal. It involves sterilizing waste by subjecting it to high temperatures and pressures through high-pressure steam. In an air-tight container, water’s boiling point increases above \(100^{\circ }\)C as the pressure rises, allowing sterilization at temperatures higher than typical boiling. For instance, blood materials, bodily fluids, and microbial debris are typically decontaminated at \(121^{\circ }\)C for 30 minutes. Once sterilized, the waste can be safely disposed of. This method is highly effective at neutralizing harmful microorganisms, significantly reducing the risk of infection transmission. By reducing the likelihood of diseases spreading across healthcare workers, waste management teams, and the public, sterilization serves as an essential safeguard. Additionally, it is an environmentally friendly option, as it produces fewer harmful emissions compared to methods like incineration.

Incineration

Incineration is a widely used and crucial method of managing hazardous materials produced in healthcare institutions, medical laboratories, and related sectors. It involves burning medical waste in a monitored environment, turning it into ash and neutralizing its hazardous properties. The process takes place in a specially designed dual-chamber furnace, where temperatures reach around 900 and 1200 degrees Celsius, ensuring complete combustion. The process is extremely beneficial in sterilizing and safely disposing of dangerous waste, including pharmaceutical remnants and other toxic materials. By incinerating waste, it eliminates harmful microorganisms, making waste safe for disposal. It also reduces solid waste volume, lowering transportation and disposal costs. To minimize environmental impact, incineration facilities are equipped with advanced pollution control systems that capture and eliminate harmful emissions.

Chemical disinfection

Chemical treatment of medical waste ensures that infectious or hazardous materials can be disposed of safely through disinfection. This method involves the use of specific chemical compounds to neutralize harmful microorganisms, such as viruses, bacteria, and fungi, commonly found in medical waste. Chemical sterilization targets a wide range of biomedical debris, including acupuncture needles, sharp objects, bodily fluids, recyclable plastics, blood, and pathogen-contaminated liquids. Typically, these materials are exposed to disinfectants, such as a 2-5% Lysol solution, before autoclaving to ensure thorough sterilization. After disinfection, chemical waste is neutralized and disposed of based on its specific properties. This approach is especially effective in dealing with pathogenic materials. When combined with other methods like autoclaving or cremation, it becomes an essential tool in medical waste management.

Microwave

Microwave sterilization is an innovative and eco-friendly method used in medical waste management (MWM). The primary goal of this technique is to significantly reduce the presence of harmful substances commonly found in healthcare facilities, research laboratories, and similar settings. By harnessing microwave technology, this method involves carefully controlled heat application to sterilize waste materials successfully, ensuring they are safe for disposal. While microwaves are traditionally associated with heating food, they have recently found a valuable role in medical waste management. This provides both safety and environmental benefits.

Landfill disposal

Land disposal is a method used in medical waste disposal where potentially hazardous waste from medical centers, laboratories, and research institutions is buried underground. When implemented correctly, this approach creates a safe, isolated environment that prevents contamination. The process typically involves digging dedicated burial sites or tunnels to dispose of waste in a controlled manner. Deep disposal is often used when other methods, like autoclaving or microwaving, aren’t practical or when regulations allow for deeper disposal options. One of the main advantages of this technique is its potential to provide a high level of containment, effectively preventing disease and contaminants spread. It is also a flexible approach, suitable for a wide range of biological waste, including lab materials, clinical waste, and pharmaceutical remnants.

Selection of MWM technologies

Choosing the most suitable method for disposing of medical waste is a critical task. In this section, we explore a case study from research conducted by Gao et al. (2024) in Jinan, China, which illustrates how BMW waste disposal techniques are currently selected75. The detailed analysis of this case study can be found in subsection (5.1). This study focuses on five distinct treatment methods for BMW disposal. The objective of this section is to determine the optimal treatment method and to develop an organization framework for implementing it.

These treatment methods are evaluated based on eight key criteria: “cost” (\(\mathfrak {L}_1\)), “waste residuals” (\(\mathfrak {L}_2\)), “health impact” (\(\mathfrak {L}_3\)), “energy consumption” (\(\mathfrak {L}_4\)), “reliability” (\(\mathfrak {L}_5\)), “volume reduction” (\(\mathfrak {L}_6\)), “treatment effectiveness” (\(\mathfrak {L}_7\)), and “public acceptance” (\(\mathfrak {L}_8\)). The description of the different methods of disposing of MWM technologies: \(\mathfrak {W} = \{\mathfrak {W}_1=\textit{Steam sterilization}, \mathfrak {W}_2=\textit{Incineration}, \mathfrak {W}_3=\textit{Chemical disinfection}, \mathfrak {W}_4=\textit{Microwave}, \mathfrak {W}_5=\textit{Landfill disposal}\}\). The structure of this case study is presented in Figure 2. Now we will proceed with the above-mentioned mathematical methods.

f, g, h-Fractional fuzzy CRITIC

In this study, the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC method is utilized to evaluate the importance of criteria and their weights. According to f, g, h-FrF CRITIC, the steps are as follows:

Step 1: Experts are categorized based on qualifications and experience using Table 4. Experts are categorized as: two are highly skilled, one is fully skilled, and two are more skilled. Expert weights are calculated using Eq.16 and their weights are \(\psi _\mathfrak {P1} = 0.2090, \psi _\mathfrak {P2} = 0.1940, \psi _\mathfrak {P3} = 0.2015, \psi _\mathfrak {P4} = 0.2015\), and \(\psi _\mathfrak {P5} = 0.1940\).

Step 2: Gather information from a group of decision makers about alternatives based on the significance of the criteria. The linguistic variables used to assess the alternatives in terms of FrFNs are shown in Table 5. The assessment values presented by the decision experts are shown in Table 6.

Step 3: A f, g, h-FrF combined decision matrix is generated by aggregating individual expert assessments. Each criterion is evaluated by aggregating all experts’ evaluations using Eq. 18 and aggregated matrix is displayed in Table 7.

Step 4: Calculate the decision score matrix using Eq. 20 and decision score matrix is displayed in Table 8.

Step 5: Compute the normalized decision matrix using Eq. 21 and normalized decision matrix is displayed in Table 9.

Step 6: Calculate the correlation coefficient using Eq. 22 and it indicates how closely one criterion is related to another. Figure 3 displays the correlation coefficient of the criterion.

Step 7: Compute the standard deviation using Eq. 23.

\(\{0.3219, 0.4368, 0.3351, 0.3534, 0.3972, 0.3351, 0.3279, 0.4129\}\)

Step 8: The information index is computed using Eq. 24.

\(\{2.0619, 3.1151, 2.5171, 3.3025, 2.5717, 2.2274, 2.5402, 3.2748\}\)

Step 9: Calculate the weights using Eq. 25

\(\{0.0954, 0.1441, 0.1165, 0.1528, 0.1190, 0.1031, 0.1175, 0.1515\}\)

f, g, h-Fractional fuzzy TOPSIS

According to f, g, h-FrF TOPSIS, the steps are as follows:

Step 10: Gather information from a group of decision makers about alternatives based on the significance of the criteria. The linguistic variables used to assess the alternatives in terms of FrFNs are shown in Table 5. The assessment values presented by the decision experts are shown in Table 6:

Step 11: A f, g, h-FrF integrated decision matrix is generated by aggregating individual expert assessments. Each criterion is evaluated by aggregating all experts’ evaluations using Eq. 27 and aggregated matrix is outlined in Table 7.

Step 12: A f, g, h-FrF aggregated decision matrix is generated by applying Eq. 29 to Table 7 and the aggregated matrix is shown in Table 10.

Step 13: f, g, h-FrF Positive and f, g, h-FrF Negative ideal solutions (PI and NI) are determined for the aggregated decision matrix Table 10 and the final results are shown in Table 11.

Step 14: Normalized Hamming distances from PI and NI are computed for each alternative and displayed in Table 12.

Step 15: A closeness coefficient is computed for each alternative and displayed in Table 12.

Step 16: Arrange the technologies in descending order \(\mathfrak {W}_1\) is the best option.

Comparative analysis

Table 13 presents a comparative analysis of various decision-making techniques applied within a fuzzy environment. The techniques under evaluation include SF-TOPSIS15, IF-TOPSIS76, F-TOPSIS77, SF-WASPAS78, IF-WASPAS79, F-WASPAS77, and the proposed f, g, h-FrF CRITIC-TOPSIS method. Throughout the analysis, MWM technology, denoted as \(\mathfrak {W}_1\), consistently emerges as the optimal choice across all methods. This highlights its robustness and reliability in making decisions. However, it is worth noting that the SF-WASPAS method ranks \(\mathfrak {W}_3\) as the superior alternative, a slight deviation from the other methods where \(\mathfrak {W}_3\) is typically ranked second. This ranking difference is likely due to variations in the weights assigned to the criteria and the inherent uncertainty of the system. Figure 4 displays the rankings of MWM technologies for all evaluated techniques.

When faced with complex decision-making scenarios within the fuzzy framework, \(\mathfrak {W}_1\) consistently stands out as the optimal choice. This finding underscores the technology’s durability and effectiveness in diverse decision contexts. Moreover, it demonstrates the versatility and efficiency of \(\mathfrak {W}_1\) in a broad spectrum of decision-making situations. By referring back to Table 13, we observe how the rankings achieved by our proposed approach compare to other methods outlined in the literature. In the f, g, and h-FrF approach, the most suitable alternative is identified. The rankings derived by other methods are relatively consistent, supporting the selection of \(\mathfrak {W}_1\) as the optimal alternative. While some discrepancies in rankings do occur, they can be attributed to factors such as incomplete data or variability in the assigned weights. Nevertheless, our analysis confirms that \(\mathfrak {W}_1\) consistently emerges as the optimal alternative, aligning with the outcomes of other methods. This consistency reinforces the effectiveness and reliability of our developed decision-making framework.

Sensitivity analysis

To explore how the FrF-based CRITIC-TOPSIS method performs and assess its impact on rankings, we vary the value of g while keeping f = 2 fixed. This sensitivity analysis helps demonstrate the robustness and reliability of the proposed methodology by reducing the uncertainties typically associated with data collection and evaluation processes. In our calculations, we set f = g = h = 2 to compute the closeness coefficient for each alternative. These closeness coefficient values ultimately determine the ranking of MWM technologies based on their performance. The results show relatively consistent rankings across all alternatives, with A4 consistently emerging as the top-performing MWM technology. A summary of the findings from this sensitivity analysis, including the ranking of alternatives, is presented in Table 14. Additionally, Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between the values of f, g, and h, and how they influence the ranking of alternatives.

Discussion

In this study, our primary goal is to tackle the complex challenge of selecting the most suitable MWM technology for sustainable development. To achieve this, we have developed a framework aimed at optimizing MWM technologies. Our approach provides a comprehensive method for assessing various MWM alternatives by taking into account a broad range of criteria, including cost, health impact, public acceptance, reliability, waste volume reduction, residual waste, treatment effectiveness, and energy consumption. The alternatives considered in this research include a variety of MWM technologies such as microwave treatment, incineration, steam sterilization, landfill disposal, and chemical disinfection, each representing a key solution available in China. By evaluating each alternative across technical feasibility, economic viability, social acceptance, and environmental impact, we gain valuable insights into how these technologies could contribute to improving China’s medical waste management sector. The decision-making process for selecting the appropriate MWM technology is inherently complex due to the multitude of factors involved.

To address this, our research establishes a reliable ranking system for MWM technologies by integrating the CRITIC and TOPSIS methods within a robust f, g, h-fractional fuzzy framework. This enables us to provide a clear and structured evaluation that supports informed decision-making. This method assesses the relationships between criteria using the CRITIC method and ranks alternatives through the TOPSIS framework. The CRITIC method is key to determining the weight of each criterion, which is based on its standard deviation and correlation with other factors. This ensures that the importance of each criterion is accurately represented in the decision-making process. On the other hand, the TOPSIS method ranks the alternatives by calculating the closeness coefficient of each option. This guarantees a well-rounded and objective evaluation that incorporates both technical and non-technical factors. To further refine the criteria weights, expert judgment is also integrated into the CRITIC method. This addition allows for expert insights, ensuring that decision-making better reflects real-world priorities. By combining the CRITIC and TOPSIS methods, this framework offers a reliable, efficient, and well-balanced approach to selecting the most appropriate MWM technology for China.

Steam sterilization appears to be the most advantageous alternative among MWM technologies in China. By disinfecting infectious health care waste, significant inactivation can be achieved. Since steam sterilization can reduce waste volume while being low cost, it is widely used in a variety of applications, supporting its effectiveness. To further validate the strength and sustainability of the proposed framework, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. The analysis showed that steam sterilization consistently performed well across various scenarios, even when key criteria were altered. The results highlighted the high operational success rate of steam sterilization, confirming that the framework is resilient to changes in input parameters. This stability enhances the model’s reliability, making it a valuable tool for decision-making in dynamic and fluctuating environments. To assess the performance of the f, g, h-FrF CRITIC-TOPSIS framework against other fuzzy MCDM methods, a comparative analysis was carried out. The comparison revealed several improvements to the system, particularly in terms of accuracy and reliability. These adjustments were made to further optimize framework performance. When compared to traditional methods, the CRITIC-TOPSIS framework stands out due to its comprehensive evaluation approach, which combines both objective data and expert judgment. This integration provides a more thorough analysis, leading to clearer insights and robust decision-making.

Through the use of multiple performance metrics, the framework highlights key strengths like consistency in rankings and stable decision-making results. However, it’s crucial to acknowledge some limitations of the current approach. Errors or biases in the input data could affect the framework’s effectiveness. Therefore, ensuring the use of high-quality data is essential for maintaining the model’s reliability. While the framework has shown promising results in the case study for China, further validation is needed to evaluate its relevance and applicability to other regions with different sector profiles. To make the framework even more flexible and efficient, additional criteria or decision-support methods could be incorporated, expanding its use to a wider range of scenarios. The CRITIC-TOPSIS framework has simplified the optimization process for MWM technologies, providing valuable insights for policymakers and stakeholders. By adopting a comprehensive and inclusive decision-making approach, it effectively addresses the complexity of selecting the right MWM technology. The study’s findings underscore the importance of managing uncertainty and integrating a diverse set of criteria into decision-making.

Managerial implications

Healthcare institutions striving to improve their decision-making processes to adopt effective MWM strategies within their operational frameworks can derive valuable insights from this study. The following key implications are particularly significant to consider:

-

The developed model integrates fractional fuzzy numbers to implement advanced decision-making methods, providing practical suggestions for healthcare managers. Through the CRITIC method, the most significant criteria for evaluating MWM strategies are health impact, waste residues, and energy consumption, based on their relative significance.

-

The health impact is a crucial criterion in MWM strategy selection, allowing decision-makers to prioritize options effectively. Accordingly, healthcare institutions and governments can make well-informed decisions when deploying sustainable MWM solutions within healthcare environments.

-

Waste residue management, including waste reduction and long-term viability, is another important consideration in the selection process. We recommend that policymakers and managers prioritize MWM strategies that minimize waste residues and reduce operational and disposal costs. Investments in efficient waste management practices will yield significant long-term benefits.

-

National policy guidelines influence energy consumption decisions. Managers should collaborate with policymakers to ensure that the selected MWM strategies align with national healthcare objectives and contribute to the sustainable development.

-

The analysis emphasizes that steam sterilization is the most effective MWM method. Healthcare managers may consider steam sterilization not only for its environmental advantages but also for its potential to offer long-term, sustainable solutions to waste treatment.

-

The sensitivity analysis conducted in this study validated the robustness of the developed model in adapting to input parameter variations. This adaptability empowers managers to make well-informed decisions amidst uncertainty, thereby ensuring the resilience of MWM investments to potential market or environmental fluctuations in the future.

Conclusion

In this study, we introduced Hamming distance and normalized Hamming distance in the context of f, g, h-fractional fuzzy sets. In addition, we developed f, g, h-FrF CRITIC method to evaluate the criteria weights and utilized novel distances in the f, g, h-FrF TOPSIS model to rank alternatives. For China to meet its MWM demands and contribute to global climate control efforts, prioritizing MWM technologies is crucial. A comprehensive framework for optimizing MWM technologies for China has been developed, taking into consideration a wide range of technical, economic, and environmental factors. According to the hybrid f, g, h-FrF-CRITIC-TOPSIS model developed in this research, steam sterilization emerges as the most suitable alternative. This is due to its low operational costs, high social acceptability, and minimal environmental impact. The sensitivity analysis underscores the significant role of the (f, g, and h) parameters in decision-making, highlighting \(\mathfrak {W}_1\) as the preferred option due to its consistently high rankings across various scenarios. A comparative analysis of various decision-making techniques developed in a fuzzy environment is applied to MWM study to check the robustness and authenticity of the proposed integrated method. This insight provides valuable guidance for decision-makers when faced with different contexts.

The results align with the actual situation and offer valuable insights into the adoption and implementation of suitable treatment technologies for MWM. However, this study has some limitations. First, the case study is based on a relatively limited number of experts, which may hinder the accuracy and reliability of the results. The arithmetic calculations of fractional fuzzy numbers are more intricate compared to crisp or fuzzy values, making calculations more challenging. A further limitation of the model is that it is only used to evaluate MWM strategies, which may not provide sufficient validation.

It is possible to improve the accuracy of the evaluation process and enhance it by incorporating a broad group of expert participants from each dimension. Computing techniques can be developed to automate operations calculations, thereby reducing the workload of experts. This model can also be used to address complex emerging challenges in fields such as agricultural reforms80, digital industry81, and disaster management82.

Data availability

The data used in this study is included in the article. Further inquiries are directed to the corresponding author.

Change history

14 November 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, Affiliation 1 contained errors and has been corrected to read: ‘School of Mathematics, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing, 210016, China.’

References

Rume, T. & Islam, S. D. U. Environmental effects of COVID-19 pandemic and potential strategies of sustainability. Heliyon, 6(9) (2020).

Padmanabhan, K. K. & Barik, D. Health hazards of medical waste and its disposal. In Energy from toxic organic waste for heat and power generation (pp. 99–118). Woodhead Publishing. (2019).

Voudrias, E. A. Technology selection for infectious medical waste treatment using the analytic hierarchy process. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 66(7), 663–672 (2016).

Zulqarnain, R. M. et al. Assessment of bio-medical waste disposal techniques using interval-valued q-rung orthopair fuzzy soft set based EDAS method. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57(8), 210 (2024).

Liu, H. C., Wu, J. & Li, P. Assessment of health-care waste disposal methods using a VIKOR-based fuzzy multi-criteria decision making method. Waste Manage. 33(12), 2744–2751 (2013).

Chakraborty, S. & Saha, A. K. A framework of LR fuzzy AHP and fuzzy WASPAS for health care waste recycling technology. Appl. Soft Comput. 127, 109388 (2022).

Darici, S., Riaz, M., Demir, G., Gencer, Z. T. & Pamucar, D. How will I break AI? Post-Luddism in the AI age: Fuzzy MCDM synergy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 202, 123327 (2024).

Lo, H. W. A novel interval neutrosophic-based group decision-making approach for sustainable development assessment in the computer manufacturing industry. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 132, 107984 (2024).

Aydin, N., Seker, S., Deveci, M. & Zaidan, B. B. Post earthquake debris waste management with interpretive-structural-modeling and decision-making-trial, and evaluation-laboratory under neutrosophic fuzzy sets. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 138, 109251 (2024).

Zhang, C., Yang, G., Wang, C. & Huo, Z. Linking agricultural water-food-environment nexus with crop area planning: a fuzzy credibility-based multi-objective linear fractional programming approach. Agric. Water Manag. 277, 108135 (2023).

Kara, K., Yalcin, G. C., Gurol, P., Simic, V. & Pamucar, D. Enhancing decision support system for finished vehicle logistics service provider selection through a single-valued neutrosophic Dombi Bonferroni-based model. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 138, 109441 (2024).

Zadeh, L. A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 8, 338–353 (1965).

Atanassov, K. T. Intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 20, 87–96 (1986).

Yager, R. R. Pythagorean fuzzy subsets. In 2013 joint IFSA world congress and NAFIPS annual meeting (IFSA/NAFIPS) (pp. 57-61). IEEE (2013).

Kutlu-Gündoğdu, F. & Kahraman, C. Spherical fuzzy sets and spherical fuzzy TOPSIS method. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 36(1), 337–352 (2019).

Mahmood, T., Ullah, K., Khan, Q. & Jan, N. An approach toward decision-making and medical diagnosis problems using the concept of spherical fuzzy sets. Neural Comput. Appl. 31, 7041–7053 (2019).

Garg, H., Munir, M., Ullah, K., Mahmood, T. & Jan, N. Algorithm for T-spherical fuzzy multi-attribute decision making based on improved interactive aggregation operators. Symmetry 10(12), 670 (2018).

Gulistan, M. et al. \(p, q, r-\) Fractional fuzzy sets and their aggregation operators and applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57(12), 1–29 (2024).

Diakoulaki, D., Mavrotas, G. & Papayannakis, L. Determining objective weights in multiple criteria problems: The critic method. Comput. Oper. Res. 22(7), 763–770 (1995).

Ke, Y., Liu, J., Meng, J., Fang, S. & Zhuang, S. Comprehensive evaluation for plan selection of urban integrated energy systems: A novel multi-criteria decision-making framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 81, 103837 (2022).

Han, X. & Rani, P. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Evaluate the barriers of blockchain technology adoption in sustainable supply chain management in the manufacturing sector using a novel Pythagorean fuzzy-CRITIC-CoCoSo approach. Oper. Manag. Res. 15(3), 725–742 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Analyzing the barriers to resilience supply chain adoption in the food industry using hybrid interval-valued fermatean fuzzy PROMETHEE-II model. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 40, 100614 (2024).

Keshavarz-Ghorabaee, M., Amiri, M., Kazimieras Zavadskas, E. & Antuchevičienė, J. Assessment of third-party logistics providers using a CRITIC-WASPAS approach with interval type-2 fuzzy sets. Transport 32(1), 66–78 (2017).

Rostamzadeh, R., Ghorabaee, M. K., Govindan, K., Esmaeili, A. & Nobar, H. B. K. Evaluation of sustainable supply chain risk management using an integrated fuzzy TOPSIS-CRITIC approach. J. Clean. Prod. 175, 651–669 (2018).

Tuş, A. & Aytaç-Adalı, E. The new combination with CRITIC and WASPAS methods for the time and attendance software selection problem. Opsearch 56, 528–538 (2019).

Wu, Y. et al. Site selection decision framework for photovoltaic hydrogen production project using BWM-CRITIC-MABAC: A case study in Zhangjiakou. J. Clean. Prod. 324, 129233 (2021).

Haktanır, E. & Kahraman, C. A novel picture fuzzy CRITIC & REGIME methodology: Wearable health technology application. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 113, 104942 (2022).

Asante, D. et al. Prioritizing strategies to eliminate barriers to renewable energy adoption and development in Ghana: A CRITIC-fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Renewable Energy 195, 47–65 (2022).

Kahraman, C., Onar, S. C. & Öztayşi, B. A novel spherical fuzzy CRITIC method and its application to prioritization of supplier selection criteria. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 42(1), 29–36 (2022).

Akram, M., Ramzan, N. & Deveci, M. Linguistic Pythagorean fuzzy CRITIC-EDAS method for multiple-attribute group decision analysis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 119, 105777 (2023).

Menekşe, A. & Akdağ, H. C. Medical waste disposal planning for healthcare units using spherical fuzzy CRITIC-WASPAS. Appl. Soft Comput. 144, 110480 (2023).

Akram, M., Zahid, S. & Deveci, M. Enhanced CRITIC-REGIME method for decision making based on Pythagorean fuzzy rough number. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 122014 (2024).

Akram, M., Azam, S., Al-Shamiri, M. M. A. & Pamucar, D. An outranking method for selecting the best gate security system using spherical fuzzy rough numbers. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 138, 109411 (2024).

Hwang, C. L., Yoon, K., Hwang, C. L. & Yoon, K. Methods for multiple attribute decision making. Multiple attribute decision making: methods and applications a state-of-the-art survey, pp. 58–191 (1981).

Akram, M., Dudek, W. A. & Ilyas, F. Group decision-making based on pythagorean fuzzy TOPSIS method. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 34(7), 1455–1475 (2019).

Liu, D. & Huang, A. Consensus reaching process for fuzzy behavioral TOPSIS method with probabilistic linguistic q-rung orthopair fuzzy set based on correlation measure. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 35(3), 494–528 (2020).

Biswas, A. & Sarkar, B. Pythagorean fuzzy TOPSIS for multicriteria group decision-making with unknown weight information through entropy measure. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 34(6), 1108–1128 (2019).

Sarkar, B. & Biswas, A. Linguistic Einstein aggregation operator-based TOPSIS for multicriteria group decision making in linguistic Pythagorean fuzzy environment. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 36(6), 2825–2864 (2021).

Ayyildiz, E. & Taskin-Gumus, A. A novel distance learning ergonomics checklist and risk evaluation methodology: A case of Covid-19 pandemic. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service Industries 31(4), 397–411 (2021).

Yildiz, A., Ayyildiz, E., Taskin-Gumus, A. & Ozkan, C. A modified balanced scorecard based hybrid pythagorean fuzzy AHP-topsis methodology for ATM site selection problem. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decision Making 19(02), 365–384 (2020).

Cheng, R. & Lin, C. T. Financial serv of wealth management banking balanced scorecard approach (2008).

Tian, Z. P., Zhang, H. Y., Wang, J. Q. & Wang, T. L. Green supplier selection using improved TOPSIS and best-worst method under intuitionistic fuzzy environment. Informatica 29(4), 773–800 (2019).

Biswas, A. & Sarkar, B. Pythagorean fuzzy TOPSIS for multicriteria group decision-making with unknown weight information through entropy measure. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 34(6), 1108–1128 (2019).

Ali, Z., Mahmood, T. & Yang, M. S. TOPSIS method based on complex spherical fuzzy sets with Bonferroni mean operators. Mathematics 8(10), 1739 (2020).

Jin, J., Zhao, P. & You, T. Picture fuzzy TOPSIS method based on CPFRS model: an application to risk management problems. Sci. Program. 2021(1), 6628745 (2021).

Akram, M., Kahraman, C. & Zahid, K. Extension of TOPSIS model to the decision-making under complex spherical fuzzy information. Soft. Comput. 25(16), 10771–10795 (2021).

Riaz, M., Batool, S., Almalki, Y. & Ahmad, D. Topological data analysis with cubic hesitant fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Symmetry 14(5), 865 (2022).

Karamoozian, A. & Wu, D. A hybrid approach for the supply chain risk assessment of the construction industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 71, 4035–4050 (2022).

Irfan, M. et al. Prioritizing and overcoming biomass energy barriers: Application of AHP and G-TOPSIS approaches. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 177, 121524 (2022).

Dhumras, H., Bajaj, R. K. & Shukla, V. On utilizing modified TOPSIS with R-norm q-rung picture fuzzy information measure green supplier selection. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 15(5), 2819–2825 (2023).

Karamoozian, A., Luo, C. & Wu, D. Risk assessment of occupational safety in construction projects using uncertain information. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 29(7–8), 1134–1151 (2023).

Dhumras, H. et al. On federated learning-oriented q-Rung picture fuzzy TOPSIS/VIKOR decision-making approach in electronic marketing strategic plans. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 70(1), 2557–2565 (2023).

Cui, Z., Taiwo, O. L. & Aaron, P. M. An application of AHP and fuzzy entropy-TOPSIS methods to optimize upstream petroleum investment in representative African basins. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 6956 (2024).

Gaeta, A., Loia, V. & Orciuoli, F. An explainable prediction method based on Fuzzy Rough Sets, TOPSIS and hexagons of opposition: Applications to the analysis of Information Disorder. Inf. Sci. 659, 120050 (2024).

Hsu, P. F., Wu, C. R. & Li, Y. T. Selection of infectious medical waste disposal firms by using the analytic hierarchy process and sensitivity analysis. Waste Manage. 28(8), 1386–1394 (2008).

Özkan, A. Evaluation of healthcare waste treatment/disposal alternatives by using multi-criteria decision-making techniques. Waste Manage. Res. 31(2), 141–149 (2013).

Aung, T. S., Luan, S. & Xu, Q. Application of multi-criteria-decision approach for the analysis of medical waste management systems in Myanmar. J. Clean. Prod. 222, 733–745 (2019).

Yazdani, M., Tavana, M., Pamučar, D. & Chatterjee, P. A rough based multi-criteria evaluation method for healthcare waste disposal location decisions. Comput. Ind. Eng. 143, 106394 (2020).

Jangre, J., Hameed, A. Z., Srivastava, M., Prasad, K. & Patel, D. Prioritization of factors and selection of best business practice from bio-medical waste generated using best-worst method. Benchmark. Int. J. 30(6), 1993–2011 (2023).

Caniato, M., Tudor, T. & Vaccari, M. International governance structures for health-care waste management: A systematic review of scientific literature. J. Environ. Manage. 153, 93–107 (2015).

Ali, M., Wang, W., Chaudhry, N. & Geng, Y. Hospital waste management in developing countries: A mini review. Waste Manage. Res. 35(6), 581–592 (2017).

Zamparas, M. et al. Medical waste management and environmental assessment in the Rio University Hospital, Western Greece. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 13, 100163 (2019).

Thakur, V. Framework for PESTEL dimensions of sustainable healthcare waste management: Learnings from COVID-19 outbreak. J. Clean. Prod. 287, 125562 (2020).

Chauhan, A., Jakhar, S. K. & Chauhan, C. The interplay of circular economy with industry 4@0 enabled smart city drivers of healthcare waste disposal. J. Cleaner Product 279, 123854 (2021).

Wei, Y., Cui, M., Ye, Z. & Guo, Q. Environmental challenges from the increasing medical waste since SARS outbreak. J. Clean. Prod. 291, 125246 (2021).

Nosheen, F. et al. Biomedical waste management associated with infectious diseases among health care professionals in apex hospitals of a typical south asian city. Environ. Res. 215, 114240 (2022).

Neves, A. C., Maia, C. C., de Castro-e-Silva, M. E., Vimieiro, G. V. & Gomes-Mol, M. P. Analysis of healthcare waste management in hospitals of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Environ. Sci. Polluti. Res. 29(60), 90601–90614 (2022).

Çelik, S., Peker, İ, Gök-Kısa, A. C. & Büyüközkan, G. Multi-criteria evaluation of medical waste management process under intuitionistic fuzzy environment: A case study on hospitals in Turkey. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 86, 101499 (2023).

Szpilko, D., de LaTorre-Gallegos, A., Jimenez Naharro, F., Rzepka, A. & Remiszewska, A. Waste management in the smart city: current practices and future directions. Resources 12(10), 115 (2023).

Nematollahi, H., Ghasemzadeh, R., Tuysserkani, M., Aziminezhad, M. & Pazoki, M. Comparative life cycle assessment of hospital waste management scenarios in Isfahan, Iran: evaluating environmental impacts and strategies for improved healthcare sustainability. Results Eng. 24, 102912 (2024).

Jungbluth, L., Goodwin, D., Tull, F. & Bragge, P. Barriers and facilitators to recycling waste in hospitals: A mixed methods systematic review 200209 (Resources, Conservation & Recycling Advances, 2024).

Anjum, M., Min, H. & Ahmed, Z. Healthcare waste management through multi-stage decision-making for sustainability enhancement. Sustainability 16(11), 4872 (2024).

Agarwal, A. K. & Sharma, K. Fuzzy-AHP methodology for ranking of hospitals based on waste management practices: A study of Gwalior City. Environ. Qual. Manage. 34(1), e22228 (2024).

Lu, C., You, J. X., Liu, H. C. & Li, P. Health-care waste treatment technology selection using the interval 2-tuple induced TOPSIS method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13(6), 562 (2016).

Gao, F., Han, M., Wang, S. & Gao, J. A novel Fermatean fuzzy BWM-VIKOR based multi-criteria decision-making approach for selecting health care waste treatment technology. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 127, 107451 (2024).

Zhang, L., Zhan, J. & Yao, Y. Intuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS method based on CVPIFRS models: an application to biomedical problems. Inf. Sci. 517, 315–339 (2020).

Kizielewicz, B. & Bączkiewicz, A. Comparison of Fuzzy TOPSIS, Fuzzy VIKOR, Fuzzy WASPAS and Fuzzy MMOORA methods in the housing selection problem. Proc. Comput. Sci. 192, 4578–4591 (2021).

Menekşe, A. & Akdağ, H. C. Medical waste disposal planning for healthcare units using spherical fuzzy CRITIC-WASPAS. Appl. Soft Comput. 144, 110480 (2023).

Schitea, D. et al. Hydrogen mobility roll-up site selection using intuitionistic fuzzy sets based WASPAS, COPRAS and EDAS. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 44(16), 8585–8600 (2019).

Rad, M. A. V. et al. A global framework for maximizing sustainable development indexes in agri-photovoltaic-based renewable systems: Integrating DEMATEL, ANP, and MCDM methods. Appl. Energy 360, 122715 (2024).

Görçün, Ö.F., Mishra, A.R., Aytekin, A., Simic, V., & Korucuk, S. Evaluation of Industry 4.0 strategies for digital transformation in the automotive manufacturing industry using an integrated fuzzy decision-making model. J. Manufact. Syst. 74, 922–948 (2024).

Peker, I., Ar, I. M., Erol, I. & Searcy, C. Leveraging blockchain in response to a pandemic through disaster risk management: an IF-MCDM framework. Oper. Manag. Res. 16(2), 642–667 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R716), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R716), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarwar, M.A., Gong, Y., Alzakari, S.A. et al. A novel Fractional fuzzy approach for multi-criteria decision-making in medical waste management. Sci Rep 15, 23999 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06184-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06184-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A robust fractional fuzzy decision support framework for sustainable energy planning

Scientific Reports (2025)