Abstract

A combined methodology was performed based on chemometrics and machine learning regressive models in estimation of polysaccharide-coated colonic drug delivery. The release of medication was measured using Raman spectroscopy and the data was used for estimation of drug delivery using machine learning models. Raman data was used along with some inputs including coating type, medium, and release time to estimate the drug release as the sole target. The study explores predictive modeling for the release variable in a dataset including 155 samples with over 1500 spectral variables. Partial least squares (PLS) was applied for dimensionality reduction, and models such as AdaBoost with linear regression, multilayer perceptron (MLP), and Theil-Sen regression were utilized, achieving the highest predictive performance with the AdaBoost-MLP model (R2 = 0.994, MSE = 0.000368). Uniquely, this work integrates glowworm swarm optimization (GSO) for model hyperparameter tuning, enhancing model accuracy and efficiency. The results suggest that spectral characteristics combined with environmental and compositional factors provide a comprehensive foundation for modeling release dynamics in evaluation of targeted colonic delivery formulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Development of targeted drug delivery formulations is a new technique for the treatment of various types of cancer. In this method, the majority of the drug molecules are delivered to the target site to enhance its therapeutic effectiveness and reduce the side effects. Polymeric nanoparticle-based drug delivery is among the most useful techniques in development of targeted drug delivery systems1,2,3. An important application of targeted drug delivery is for colonic treatment where the formulation must be released in the desired site. The formulation can be coated with polymeric materials which are sensitive to gastrointestinal (GI) physiology4. As such, screening materials and formulations for colonic targeted delivery is challenging and sophisticated methods are required.

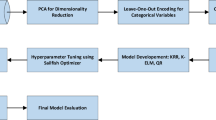

An important aspect of targeted drug delivery is the release of medication as a function of formulation parameters. Also, the release is a function of the targeted environment and can be tuned by adjusting the medium and formulation parameters5,6. Therefore, the drug release from drug delivery vehicles is a function of coting materials, formulation properties, time, and the medium. Understanding the drug release versus the input parameters is challenging and extensive measurements are required. Computational methods can be exploited to avail their benefits for reducing the screening, design, and optimization of targeted drug delivery formulations7. Data-driven methods such as machine learning (ML) can be employed for evaluation of the effect of input parameters on the drug release behavior for colonic drug delivery formulations. Some measurements datasets are required to build the model and validate it. Once validated, the model can be used for a variety of conditions to estimate the drug release. Abdalla et al.4 developed machine learning approach for analysis of colonic release of drug from polysaccharide-coated formulations, and implemented Raman tool for measurement of drug release. They used the measured drug release dataset reported in8 for building the predictive models. Recently, AlOmari and Almansour9 developed a combined methodology with PCA (Principal Component Analysis) and ML-based regressive models for estimating drug release from polysaccharide-coated medicine.

In the past few years, ML has gained significant traction for solving complex problems in various scientific domains, particularly in biochemical research where high-dimensional datasets are prevalent. This study focuses on applying ML techniques to predict the release behavior of biochemical substances, leveraging a dataset containing 155 samples with over 1500 spectral variables alongside time, medium, and polysaccharide type as additional inputs. The formulation parameters are combined with Raman spectral data to predict the drug release. By utilizing machine learning, the aim is to model intricate relationships between these variables to understand how spectral characteristics, environmental factors, and compositional attributes influence the release behavior of the drug.

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is employed to reduce the dimensionality of data. Following dimensionality reduction, several predictive models are applied, including AdaBoost combined with Linear Regression, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and Theil-Sen Regression. AdaBoost, an ensemble learning algorithm, improves model performance by focusing on difficult-to-predict samples in each iteration, thereby reducing bias and variance. Among the models tested, the AdaBoost-MLP model had the best prediction performance, making it ideal for detecting non-linear correlations in data.

A key innovation in this work is the application of glowworm swarm optimization (GSO) for hyperparameter tuning. This novel approach improves model accuracy and computational efficiency by mimicking the behavior of glowworms to search for optimal parameter configurations. The integration of GSO enhances the performance of the predictive models, particularly in handling the complexity of the high-dimensional dataset. In fact, the models and optimization tool used in this study are different than those reported by AlOmari and Almansour9 for prediction of drug release.

The contributions of this paper are threefold. First, we successfully integrate advanced machine learning techniques, including dimensionality reduction, ensemble learning, and optimization, to model the release dynamics of biochemical substances with high accuracy. Second, the AdaBoost-MLP model demonstrated exceptional predictive power, outperforming other models. Third, the use of GSO for hyperparameter tuning is a novel contribution, offering an adaptive and efficient method for improving model performance. These results underscore the importance of combining spectral characteristics with compositional factors to provide a comprehensive foundation for predicting drug release dynamics. This study sets the stage for future research in applying machine learning techniques to complex biochemical datasets.

Dataset and visualization

A total of 155 data points is used in this study. The primary variable of interest is release, which we aim to predict using a variety of input features4,8. The dataset comprises more than 1,500 variables derived from spectral data, providing detailed information about the samples’ spectral properties and taken from previous works4,8. It also includes a numerical feature, time, representing the experimental duration. In addition, two categorical attributes—medium and the name of the polysaccharide used as a coating—reflect environmental conditions and material composition that may affect release behavior9. Together, these varied inputs offer a strong basis for studying and modeling the dynamics of substance release.

Figures 1 and 2 present a comparative analysis of the mean release values based on two key factors: experimental medium and polysaccharide name. In Fig. 1, the mean release is categorized by different media, highlighting the impact of environmental conditions on release behavior. Meanwhile, Fig. 2 focuses on the variation in mean release across different polysaccharide types, illustrating how compositional differences influence the release rate. Together, these figures provide a comprehensive view of the factors affecting release dynamics in the experimental setup.

One-hot encoding

To effectively utilize the categorical variables, “medium” and “polysaccharide name”, we apply one-hot encoding. This procedure converts each categorical value into a new binary column that represents the existence or absence of the category. For instance, if a variable contains three distinct categories, it will be converted into three binary columns. This encoding ensures that the model can interpret categorical data appropriately, as it eliminates any ordinal relationships that may not exist among the categories.

This method converts each unique category into a binary vector, where a single ‘1’ and multiple ‘0s’ represent the presence or absence of a category. This ensures the model interprets these variables without implying any ordinal relationship, which is essential for our regression analysis of drug release dynamics.

PLS for dimensionality reduction

We utilized PLS method to mitigate the high dimensionality of the spectral characteristics. PLS is especially proficient in extracting latent variables that encapsulate the information inside the spectral data while maintaining the correlation with the output variable10. By selecting an optimal number of components through cross-validation, we can reduce the complexity of the model without sacrificing predictive power. This reduction facilitates a more efficient analysis of the spectral characteristics related to the release behavior.

In other words, PLS was employed for dimensionality reduction due to its effectiveness in handling high-dimensional data with correlated variables, such as the spectral data in this study comprising over 1500 variables. PLS identifies latent variables that maximize the covariance between the predictors (spectral data) and the response variable (drug release), ensuring that the reduced set of features retains the most relevant information for prediction. Additionally, as a supervised method, PLS is particularly suitable for this predictive modeling task compared to unsupervised techniques like principal component analysis (PCA), as it explicitly accounts for the relationship with the target variable. To identify the optimal number of PLS components, cross-validation was employed, selecting the component count that resulted in the lowest mean squared error (MSE), as shown in (Fig. 3). This method helps achieve a balance between model simplicity and predictive performance.

Figure 3 shows the cross-validation mean squared error (MSE) for the various PLS components utilized in the model. The graph demonstrates how the number of PLS components influences the model’s error rate, with the goal of selecting the optimal number of components that minimize the MSE. This figure is crucial for determining the balance between model complexity and predictive accuracy, ensuring that an appropriate number of components is chosen for optimal performance.

PLS was selected for its strong ability to manage multicollinearity among predictors and to capture intricate relationships between measured variables and underlying latent factors, even when working with small datasets. This makes it especially effective for exploratory studies focused on prediction and the formulation of new theoretical insights, rather than strictly testing existing theories.

The number of latent factors was determined based on cross-validation and the minimum root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP). To avoid overfitting, we ensured that the number of factors retained did not exceed the point where RMSEP began to increase. In our analysis, [insert number] factors were selected, which provided an optimal balance between explanatory power and model parsimony.

Isolation forest for outlier detection

To ensure the integrity of the data and improve the robustness of our model, we implement the Isolation Forest algorithm for outlier detection. This unsupervised learning technique identifies anomalous data points by isolating them from the rest of the data. The algorithm operates by constructing decision trees that partition the data points, ultimately revealing observations that deviate significantly from the norm.

Min-max scaler

To standardize the range of the numeric variable “time” and the reduced spectral features, we apply a Min-Max scaling technique. This normalization method transforms the data to a uniform range, typically between 0 and 1. By rescaling the features, we enhance the model’s convergence during training and mitigate the impact of varying scales among input variables. This stage is crucial for algorithms affected by the scale of the input data, guaranteeing that each feature contributes proportionately to the model’s effectiveness.

Methodology

AdaBoost

AdaBoost, derived from Adaptive Boosting, is an ensemble learning technique that improves performance through the amalgamation of multiple base (or weak) prediction models. AdaBoost improves the performance of base predictors by updating instance weights based on prior predictors’ performance11,12.

The key feature of AdaBoost is its adaptive enhancement of basic models, making it capable of addressing complex problems. While simple models offer strong generalization due to their simplicity, they often struggle with complex problems due to significant bias. On the other hand, complex models, although potentially more accurate, are prone to overfitting and are challenging to implement in practice. AdaBoost tackles these difficulties by iteratively modifying the weights of erroneously predicted instances. This allows succeeding models to focus more on tough cases, minimizing bias and variation11,13.

Linear regression

Another base model used in this research is linear regression, a basic learning method applied in regression analysis. The normality assumption, a fundamental component of the linear regression model, is represented by the following equation14:

Here, \(\:x\) represents the independent (input) variable of the model, while \(\:\text{y}\) denotes the output. In Linear Regression (LR), the objective is to minimize the sum of squares15,16.

Here, \(\:{y}_{k}\) indicates the experimental value of data point k, \(\:{\overline{y}}_{k}\) is the mean of \(\:{y}_{k}\) across all n data rows, and \(\:\widehat{{y}_{k}}\) signifies the predicted value for instance k.

Multilayer perceptron (MLP)

A widely used neural network framework adaptable to diverse machine learning applications, including regression, is the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). MLP regression excels at capturing non-linear, complex correlations between input variables and continuous outcome variables17,18.

An MLP has one input layer, typically several (and maybe one) hidden layer, and an output layer—many artificial neurons layered one upon another. Every neuron in the intermediate and output layers is closely connected to the neurons in the one below layer.

Consider X as the input data comprising n features: \(\:X=\left[{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\dots\:,{x}_{n}\right]\).

Following equation is representation of hidden layer:

Here, \(\:{h}_{j}\) denotes the output from the j-th hidden layer neuron, $\sigma$ refers to the activation function—commonly a non-linear function such as ReLU or sigmoid—while \(\:{w}_{ij}^{\left(1\right)}\) signifies the weight associated with the connection between the j-th neuron and the i-th input. The output layer can be denoted as19,20:

Optimization techniques include Adam and Stochastic Gradient Descent. In MLP regression, the loss function is represented mathematically as follows19:

Theil-Sen regression (TSR)

A non-parametric approach for modelling linear relationships within a dataset is the Theil-Sen regression method. This method avoids particular presumptions about error distribution and shows robustness to outliers. By use of median of slopes among all possible pairings of data points, Theil-Sen regression emphasizes on determining the ideal slope of the line that best fits the data21,22.

In the presence of a dataset \(\:\left\{\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1}\right),\left({x}_{2},{y}_{2}\right),\dots\:,\left({x}_{n},{y}_{n}\right)\right\}\), the formula for the Theil-Sen slope estimator is stated as23:

Here, \(\:\widehat{{{\upbeta\:}}_{TS}}\) represents the estimated slope, \(\:{y}_{i}\) and \(\:{x}_{i}\) denote the i-th response and predictor variables, and n signifies the sample size.

Subtracting the median of the x-values from the median of the y-values yields the line’s intercept24:

The Theil-Sen regression line is therefore expressed as25:

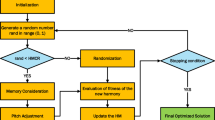

Glowworm swarm optimization (GSO)

The hyperparameter tuning was executed via Glowworm Swarm Optimization (GSO). Generalized Support Vector Optimization (GSO) was specifically developed to address optimization problems in many domains, including clustering, different matching problems, and routing26,27. For this method, glowworms utilize variations in their bioluminescent intensity to facilitate interaction and attraction among peers. They exhibit a natural preference for brighter counterparts while avoiding those with lower luminosity, thereby navigating their surroundings to maintain an effective equilibrium between diversification and intensification28,29.

In the optimization stage of the GSO algorithm, a group of artificial fireflies symbolizes candidate solutions for the given problem. A spatial distance matrix is employed to record the pairwise separations between these fireflies, facilitating their interactions and movement dynamics. The luminosity of each firefly signifies its effectiveness as a remedy. Through multiple cycles, these synthetic glowworms adjust their places according to established norms. These regulations involve mechanisms of attraction and aversion30.

Every glowworm’s individual fitness and the luminosity emitted by surrounding glowworms define its bioluminescent intensity. This adaptive strategy lets glowworms modify their behavior depending on the quality of the solutions they come across in their near surroundings. The GSO procedure is depicted in (Fig. 4).

Results and discussion

Here, we outline the results achieved by different predictive models on our dataset. Evaluation measures such as R², MSE, and MAE offer insights into training and test data sets (80 − 20 ratio). Additionally, we compare the effectiveness of models such as AdaBoost-LR, AdaBoost-MLP, and AdaBoost-TSR to determine their accuracy and consistency in predicting the release variable. In this study, 5-fold cross-validation was used to evaluate predictive models on a dataset of 155 samples with over 1500 spectral variables, reduced via PLS regression. The method trained on four folds and tested on one, repeated five times. Metrics like R², MSE, and MAE were averaged across folds9.

From the analysis of Tables 1 and 2, the AdaBoost-MLP model demonstrates superior performance compared to both AdaBoost-LR and AdaBoost-TSR across multiple key metrics. As detailed in Table 1, the AdaBoost-MLP model attains the superior coefficient of determination (R²) scores, registering values of 0.996146 and 0.994043, respectively. These values indicate that the model explains nearly all of the variance in the release variable, outperforming the other models, particularly AdaBoost-LR, which achieved a lower R² on the test data (0.964364), and AdaBoost-TSR, which scored slightly lower at 0.992149.

In terms of error rates, the AdaBoost-MLP model consistently shows the lowest Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in both the training and test datasets, as outlined in Table 2. The test MSE of 0.000368 and MAE of 0.017094 confirm the model’s accuracy in estimation of the release variable. Comparatively, the AdaBoost-LR model has higher error rates, with a test MSE of 0.001969 and MAE of 0.036968, while AdaBoost-TSR follows closely behind with a test MSE of 0.000476 and MAE of 0.018645. This indicates that AdaBoost-MLP has better generalization capabilities, handling unseen data more effectively.

Visual confirmation in Figs. 5, 6 and 7 further supports these results. In Fig. 6, the experimental versus predicted values for the AdaBoost-MLP model show an almost perfect alignment, signifying the model’s exceptional predictive power9. In contrast, both AdaBoost-LR (Fig. 5) and AdaBoost-TSR (Fig. 7) exhibit more noticeable deviations between experimental and predicted values, highlighting the comparative advantage of AdaBoost-MLP in accuracy.

Additionally, the learning curve depicted in Fig. 8 demonstrates the AdaBoost-MLP model’s stability and efficiency during training. The model quickly converges to a low-error rate, maintaining consistency throughout the learning process. This smooth convergence is a critical advantage, as it indicates that the AdaBoost-MLP model not only performs well but also does so without overfitting or underfitting, making it the most reliable choice among the models tested. It shows agreement and similarity with the results reported by AlOmari and Almansour9 which used the same dataset and different ML algorithms.

In conclusion, according to the comprehensive analysis of Tables 1 and 2, as well as Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8, the AdaBoost-MLP model is the best-performing one in predicting the release variable. Its superior R², lower error rates, and strong visual validation through experimental fit and learning curve stability confirm its effectiveness over the other models evaluated in this study.

Conclusion

This research effectively showcases the potential of advanced ML approaches, particularly ensemble models, to accurately predict complex biochemical variables such as the release dynamics within a controlled experimental framework. Among the models explored, AdaBoost combined with a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) proved to be the most accurate, achieving an R² of 0.994 and a low Mean Squared Error (MSE) of 0.000368 on the test dataset, indicating excellent predictive capability and generalizability. The study addressed the challenge of high-dimensional spectral data through Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, which reduced data complexity and preserved essential correlations with the target variable. This approach not only minimized overfitting but also optimized the training process, allowing for more efficient analysis.

An important characteristic of this research is the application of the GSO algorithm for optimizing hyperparameters. This novel application of GSO enabled an adaptive and efficient search through the parameter space, improving model accuracy while minimizing computational resources. By leveraging the unique luminescent-based mechanisms of GSO, the study was able to enhance the performance of machine learning models, particularly in handling complex datasets with numerous interdependent variables.

The results highlight that combining spectral characteristics with environmental and compositional factors provides a comprehensive foundation for modeling release dynamics. The findings underscore the effectiveness of integrating dimensionality reduction and hyperparameter tuning techniques in predictive modeling tasks, especially those involving high-dimensional and heterogeneous data. Additionally, the analysis of time, medium, and polysaccharide type as influential factors offers valuable insights into the fundamental drivers of release behavior, which could inform both future experimental designs and predictive modeling efforts in biochemical research.

Overall, this study demonstrates the effectiveness of applying machine learning techniques to understand and predict release dynamics, establishing a promising approach for similar investigations in biochemical and pharmaceutical research domains. Future work could explore the integration of additional feature selection techniques and the application of other optimization algorithms to further enhance model interpretability and efficiency.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alhodieb, F. S. et al. Chitosan-modified nanocarriers as carriers for anticancer drug delivery: promises and hurdles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 217, 457–469 (2022).

Gandhi, A., Jana, S. & Sen, K. K. In-vitro release of acyclovir loaded Eudragit RLPO® nanoparticles for sustained drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 67, 478–482 (2014).

Krishnaswami, V. et al. Nanotechnology-based advancements for effective delivery of phytoconstituents for ocular diseases. Nano TransMed. 100056 (2024).

Abdalla, Y. et al. Machine learning of Raman spectra predicts drug release from polysaccharide coatings for targeted colonic delivery. J. Controlled Release. 374, 103–111 (2024).

Boehler, C., Oberueber, F. & Asplund, M. Tuning drug delivery from conducting polymer films for accurately controlled release of charged molecules. J. Controlled Release. 304, 173–180 (2019).

Raza, A. et al. Endogenous and exogenous Stimuli-Responsive drug delivery systems for programmed Site-Specific release. Molecules 24 (6), 1117 (2019).

Wang, W. et al. Computational pharmaceutics - A new paradigm of drug delivery. J. Controlled Release. 338, 119–136 (2021).

Ferraro, F. et al. Colon targeting in rats, dogs and IBD patients with species-independent film coatings. Int. J. Pharmaceutics: X. 7, 100233 (2024).

AlOmari, A. K. & Almansour, K. Chemometric and computational modeling of polysaccharide coated drugs for colonic drug delivery. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 14694 (2025).

Maitra, S. & Yan, J. Principle component analysis and partial least squares: two dimension reduction techniques for regression. Appl. Multivar. Stat. Models 79, 79–90 (2008).

Schapire, R. E. Explaining adaboost. Empirical inference: Festschrift in Honor of Vladimir N. Vapnik, 37–52 (2013).

Stamp, M. Boost your knowledge of adaboost. (2017).

Bahad, P. & Saxena, P. Study of adaboost and gradient boosting algorithms for predictive analytics. In International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Smart Communication 2019: Proceedings of ICSC 2019. (Springer, 2020).

Poole, M. A. & O’Farrell, P. N. The assumptions of the linear regression model. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 145–158. (1971).

Pombeiro, H. et al. Comparative assessment of low-complexity models to predict electricity consumption in an institutional building: linear regression vs. fuzzy modeling vs. neural networks. Energy Build. 146, 141–151 (2017).

Kim, M. K., Kim, Y. S. & Srebric, J. Predictions of electricity consumption in a campus Building using occupant rates and weather elements with sensitivity analysis: artificial neural network vs. linear regression. Sustainable Cities Soc. 62, 102385 (2020).

Cichy, R. M. & Kaiser, D. Deep neural networks as scientific models. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23 (4), 305–317 (2019).

Mielniczuk, J. & Tyrcha, J. Consistency of multilayer perceptron regression estimators. Neural Netw. 6 (7), 1019–1022 (1993).

Riedmiller, M. & Lernen, A. Multi layer perceptron. Machine Learning Lab Special Lecture, University of Freiburg, 7–24 (2014).

Almehizia, A. A. et al. Numerical optimization of drug solubility inside the supercritical carbon dioxide system using different machine learning models. J. Mol. Liq. 392, 123466 (2023).

Theil, H. A rank-invariant method of linear and polynomial regression analysis. Indagationes Math. 12 (85), 173 (1950).

Sen, P. K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 63 (324), 1379–1389 (1968).

Kumari, S. et al. Evaluation of gene association methods for coexpression network construction and biological knowledge discovery. PloS One 7 (11), e50411 (2012).

Ohlson, J. A. & Kim, S. Linear valuation without OLS: the Theil-Sen Estimation approach. Rev. Acc. Stud. 20 (1), 395–435 (2015).

Wilcox, R. A note on the Theil-Sen regression estimator when the regressor is random and the error term is heteroscedastic. Biometrical Journal: J. Math. Methods Biosci. 40 (3), 261–268 (1998).

Krishnanand, K. & Ghose, D. Glowworm swarm optimisation: a new method for optimising multi-modal functions. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Stud. 1 (1), 93–119 (2009).

Krishnanand, K. N. & Ghose, D. Detection of multiple source locations using a glowworm metaphor with applications to collective robotics. In Proceedings 2005 IEEE Swarm Intelligence Symposium, 2005. SIS 2005 (IEEE, 2005).

Zhou, Y. et al. A glowworm swarm optimization algorithm based tribes. Appl. Math. Inform. Sci. 7 (2), 537–541 (2013).

Wu, B. et al. The improvement of glowworm swarm optimization for continuous optimization problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 39 (7), 6335–6342 (2012).

Kalaiselvi, T., Nagaraja, P. & Basith, Z. A. A review on glowworm swarm optimization. Int. J. Inf. Technol. (IJIT) 3 (2), 49–56 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anupam Yadav: Writing, Investigation, Validation, Software, Supervision.Jayaprakash B.: Writing, Investigation, Validation, Software, Conceptualization. Laith Hussein Jasim: Writing, Methodology, Validation, Software. Mayank Kundlas: Writing, Investigation, Validation, Software, Conceptualization.Maan Younis Anad: Writing, Methodology, Validation, Software.Ankur Srivastava: Writing, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Resources.M. Janaki Ramudu: Writing, Validation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.Bharathi B.: Writing, Investigation, Validation, Software, Conceptualization.Prabhat Kumar Sahu: Writing, Resources, Validation, Software, Conceptualization. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yadav, A., Jayaprakash, B., Jasim, L.H. et al. Implementing partial least squares and machine learning regressive models for prediction of drug release in targeted drug delivery application. Sci Rep 15, 22461 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06227-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06227-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Combination of machine learning and Raman spectroscopy for prediction of drug release in targeted drug delivery formulations

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

SERS Spectral Monitoring of Oxytetracycline In-Vitro Pharmacokinetics Quantification from Antibacterial Stimuli Responsive PVA/AgO Nanobiocomposite Hydrogel Along with Multivariate Data Analysis Techniques

Plasmonics (2025)