Abstract

In the central region of the Lower Shihezi Formation within the Hangjinqi Gas Field, Ordos Basin, China, gas-bearing tight sandstone reservoirs exhibit a coexistence of low-resistivity and medium-to-high-resistivity characteristics. These reservoirs are characterized by significant resistivity fluctuations, posing challenges to the accurate calculation of gas saturation using the classical Archie equation and its derivatives. Consequently, both qualitative and quantitative evaluations of gas-bearing tight sandstone reservoirs are often hindered. To address these complexities, a comprehensive analysis was conducted utilizing an integrated dataset comprising mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP), conventional thin-section petrography, whole-rock and clay mineral analyses, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), natural gamma ray (GR), spontaneous potential (SP), deep and shallow lateral resistivity (LLD and LLS), array induction resistivity (HDIL), acoustic travel time (AC), density (DEN), neutron (CNL), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) logging data. The results demonstrate that among various factors influencing resistivity—including sedimentary characteristics, clay mineral distribution, porosity, pore structure, and gas content—porosity within distinct pore size ranges is the primary controlling factor driving resistivity variations. Specifically, analysis of NMR T2 spectrum data reveals that low resistivity is predominantly associated with porosity in the 3–12 ms pore size range, while high resistivity is primarily controlled by porosity in ranges exceeding 24 ms and below 12 ms. These findings enhance the understanding of the mechanisms underlying resistivity fluctuations in gas-bearing reservoirs. This understanding is essential for improving the accuracy of reservoir identification and optimizing development strategies, offering valuable insights for the exploration and exploitation of similar reservoirs worldwide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low-resistivity tight sandstone reservoirs have become a focal point for extensive research and development worldwide, resulting in significant production achievements1,2,3,4,5,6,7. These reservoirs are generally characterized by three key criteria: (1) a relatively low resistivity value, with specific thresholds varying across different oil and gas fields due to the absence of a standardized measure8; (2) a resistivity increase ratio of less than 2 or 3 when compared to adjacent water reservoirs within wells9,10; and (3) a resistivity close to or less than 1.5 times that of adjacent shale formations. Reservoirs meeting any one of these criteria are classified as low-resistivity tight sandstone reservoirs11,12,13. The formation of low-resistivity tight sandstone reservoirs is influenced by several factors, including the presence of conductive minerals, high shale or clay mineral content, elevated water saturation, and the invasion of drilling fluids14,15,16,17,18. For instance, the low resistivity observed in the Simpson Formation in the United States is attributed to conductive minerals, while laminated shaly sands explain similar characteristics in the Gulf Coast19,20,21. In India’s Cambay Basin, reservoirs in the Gandhar and Ankleshwar oilfields exhibit low resistivity due to high capillary-bound water and extensive microporosity22. Similarly, low resistivity in the Malay Basin is associated with complex clay content23. Typically, low-resistivity tight sandstone reservoirs are characterized by fine grain sizes, such as fine sand or siltstone, where high bound water content significantly enhances conductivity, thereby lowering resistivity24,25,26. However, the low-resistivity tight sandstone reservoirs of the Lower Shihezi Formation in the Hangjinqi Gas Field, Ordos Basin, China, differ in that they primarily comprise coarser grain sizes, including medium sandstone, coarse sandstone, and gravelly coarse sandstone27,28,29. Additionally, this formation exhibits a coexistence of low-, medium-, and high-resistivity sandstone reservoirs. Notably, even within the same sandstone reservoir, resistivity can vary significantly despite similarities in grain size and shale content between upper and lower sections, leading to substantial resistivity fluctuations. These complexities underscore the diverse resistivity characteristics of gas-bearing reservoirs in this field. Interestingly, whether a reservoir exhibits low or high resistivity, it tends to demonstrate relatively high production capacity. This makes accurate water saturation calculations using the classical Archie equation and its derivatives particularly challenging. Although many scholars have systematically categorized and optimized the parameters of the Archie equation and its derivatives, thereby improving the accuracy of water saturation calculations30,31they have not fundamentally altered the core principle that resistivity, as a critical input parameter, remains closely associated with water saturation. Should the relationship between resistivity and water saturation become invalid, the water saturation evaluation model would require substantial refinement to ensure the precision of both qualitative and quantitative assessments of the reservoir in the study area. Consequently, investigating the causes of resistivity fluctuations becomes critically important, as it directly impacts the evaluation results of reservoir water saturation and, by extension, the effectiveness of development strategies.

Previous studies have established that the Lower Shihezi Formation in the Hangjinqi Gas Field is a low-porosity, low-permeability tight sandstone reservoir with complex gas-water relationships32,33,34,35. Factors such as shale content, micropore development, brine salinity, and drilling fluid invasion have been identified as contributors to the formation of low-resistivity gas-bearing reservoirs, with micropore development being the primary influencing factor36. However, there has been limited research on the resistivity characteristics of reservoirs dominated by coarse sandstone and gravelly coarse sandstone, where similar shale content may coexist with significant resistivity variations between different sections of the same sandstone reservoir. To accurately determine the critical control factors responsible for resistivity fluctuations in tight sandstone reservoirs predominantly composed of medium-to-coarse grains within the study area, this study performs a comprehensive analysis leveraging core measurement data, geophysical logging data, and actual production data. The research findings can serve as a technical foundation for assessing the applicability of the Archie water saturation calculation model, which primarily relies on resistivity as an input parameter, within the study area. This approach reduces the error rate associated with misclassifying low-resistivity tight sandstone reservoirs as water reservoirs or low-yield gas-bearing water reservoirs, thereby significantly improving the accuracy of gas content identification in the reservoirs. Furthermore, it provides technical support for enhancing reservoir evaluation methodologies and optimizing gas field development strategies while offering valuable insights into the precise assessment of globally analogous tight sandstone gas reservoirs exhibiting similar resistivity fluctuations.

Geological setting

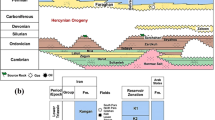

The Hangjinqi Gas Field is situated in the northern part of the Ordos Basin, China, and is geographically adjacent to the Sulige Gas Field to the south. Structurally, it lies at the convergence of the Yishan Slope and the Yimeng Uplift, forming a transitional geological setting (Fig. 1(a),1(b))37. Gas-bearing sandstone reservoirs in this region are predominantly distributed within the Carboniferous Taiyuan Formation and the Permian Shanxi and Lower Shihezi Formations36. The central portion of the Hangjinqi Gas Field is characterized by a braided river depositional system formed on a north-south oriented alluvial plain. The sedimentary thickness averages approximately 130 meters38. Stratigraphically, the Lower Shihezi Formation is in direct erosional contact with the underlying Shanxi Formation and conformably overlain by the Upper Shihezi Formation39. The lithology of the Lower Shihezi Formation is dominated by gray and gray-white gravelly coarse-grained sandstones interbedded with fine-grained sandstones, along with sporadic gray, brown, and red mudstones. This lithological assemblage reflects dynamic fluctuations in the sedimentary water level, indicative of a high-energy depositional environment. The primary lithotypes are lithic sandstone and lithic quartz sandstone40displaying relatively coarse grains and poor sorting—characteristic features of proximal source sedimentation.

Based on sedimentary cyclicity, the Lower Shihezi Formation is subdivided into three members: He-1, He-2, and He-3, arranged in ascending stratigraphic order(Fig. 1(c)). Serving as the principal gas-producing horizon in the study area, the Lower Shihezi Formation represents a classic low-porosity, low-permeability tight sandstone reservoir29. Its pronounced heterogeneity and complex pore evolution processes are attributed to multiple diagenetic alterations, including compaction, cementation, and dissolution. These diagenetic processes significantly impact reservoir quality and contribute to the reservoir’s intricate spatial variability41.

Methods

The study primarily focuses on several key factors that may significantly influence resistivity, including the reservoir’s sedimentary environment, types of clay minerals, porosity contributions from different pore sizes, pore structure, and gas content, to systematically investigate their impact on resistivity.The work is mainly conducted in the following three aspects.

-

(1)

To avoid errors in measurement results from different logging instruments, the geophysical logging data of 10 wells within the study area were optimally selected. These data were collected by the same set of ECLIPS5700 logging instruments belonging to the same measurement unit affiliated with Sinopec Group, ensuring the standardization and comparability of logging data among different wells. Meanwhile, the logging data of GR, SP, LLD, HDIL, AC, DEN, CNL, and NMR for the 10 wells were analyzed. Based on the development experience of the Hangjinqi Gas Field, the GR, AC, DEN, and CNL were employed to identify the tight sandstone reservoirs of the Lower Shihezi Formation (Table 1).

-

(2)

The LLD values of the Lower Shihezi Formation reservoir were systematically extracted for statistical analysis, and the variation characteristics of these values within the He-3, He-2, and He-1 Members were analyzed. Furthermore, along the paleocurrent direction (from north to south), six representative wells (X1 - X6) were selected for inter-well correlation using GR and LLD datasets, enabling a clearer understanding of the spatial resistivity variations in the subsurface reservoir.

-

(3)

A total of 28 sets of clay mineral and MIP data, 100 sets of conventional thin sections, and 20 sets of SEM measurement data were collected from the tight sandstone reservoirs in the Lower Shihezi Formation across ten wells within the study area. Through comprehensive analysis of these datasets, the proportions of rock matrix particle sizes at various depths, the compositions of clay minerals (including illite-smectite mixed layers, illite, kaolinite, and chlorite), and mercury injection parameters (including P50, Pd, λi, λo, D, α, C, Rmax, R, R50, Gg, Sp, φp, Skp, and DM) were obtained. Subsequently, these parameters were depth-calibrated against logging curves, and LLD values at corresponding depths were extracted for correlation analysis to quantify the impacts of rock matrix particle size, clay mineral content, and pore structure on LLD resistivity fluctuations. Finally, detailed analyses were conducted on the correlations between the T2 spectrum of NMR and the array resistivity data of HDIL with respect to LLD fluctuations, elucidating the effects of pore volume fractions for different pore diameters and the influence of increasing gas content on LLD resistivity.

Through a comprehensive analysis of the correlation coefficients between each parameter obtained from the aforementioned steps and LLD, the parameter exhibiting the highest correlation coefficient (significantly higher than the others) can be identified as the primary controlling factor responsible for resistivity fluctuations. Parameters with lower correlation coefficients are considered secondary factors. Ultimately, this analysis elucidates the various potential factors that control significant changes in resistivity across both low-resistivity and medium-to-high-resistivity reservoirs within the study area.

Results

Characteristics of reservoir resistivity

In the absence of a standardized criterion for delineating medium and high-resistivity tight sandstone reservoirs, the tight sandstone reservoirs of the Lower Shihezi Formation in the study area are classified into two categories: low resistivity and medium-high resistivity reservoirs, for detailed investigation. This paper delineates low-resistivity gas-bearing sandstone reservoirs by the second criterion defined in the introduction, specifically that the relative increase in resistivity compared to adjacent water reservoirs is less than 3. Upon statistical analysis of the LLD logging values, the resistivity range of the water layer in the Lower Shihezi Formation of the study area is 3 to 5 Ω·m. Using three times the maximum value as the delimiting criterion, a resistivity of less than 15 Ω·m is classified as a low-resistivity reservoir, while a resistivity of 15 Ω·m or greater is classified as a medium-to-high resistivity reservoir. Based on the analysis of actual production data, both the low-resistivity reservoir and the medium-high resistivity reservoir in the Lower Shihezi Formation of the study area can achieve industrialized production capacity. For example, in the low resistivity reservoir of the He-2 Member of Well X7, the average resistivity of the perforated interval is 8.2 Ω·m, with daily gas and water production of 6,008 m³ and 7.1 m³, respectively (Fig. 2(a)). In the high resistivity reservoir of the He-3 Member of Well X11, the average resistivity of the perforated interval is 91 Ω·m, with daily gas production of 8,526 m³ without water (Fig. 2(b)). The variability in the resistivity of gas-bearing reservoirs significantly increases the complexity of reservoir evaluation.

The logging data from 10 wells in the study area were statistically analyzed. The LLD values of the sandstone reservoirs in the Lower Shihezi Formation ranged from 3.5 to 226.4 Ω·m, with the main frequency distribution between 3.5 and 32 Ω·m. Specifically, the resistivity distribution range for the He-3 Member was 3.5 to 61.4 Ω·m, with the main frequency distribution between 4 and 24 Ω·m; for the He-2 Member, the resistivity distribution range was 6.4 to 108.3 Ω·m, with the main frequency distribution between 6 and 22 Ω·m; for the He-1 Member, the resistivity distribution range was 5.3 to 226.4 Ω·m, with the main frequency distribution between 10 and 38 Ω·m. These results indicate that from the He-3 Member to the He-1 Member, as the formation compaction increases, the main frequency of the resistivity distribution gradually increases. A detailed statistical analysis of reservoir thickness was performed. Among the 10 wells, the total thickness of the low-resistivity reservoir in the Lower Shihezi Formation was 235.6 m, representing 35% of the total thickness. In contrast, the total thickness of the medium- and high-resistivity reservoirs was 435.3 m, accounting for 65% of the total thickness. Through an inter-well resistivity comparison of the sandstone reservoirs within the Lower Shihezi Formation across six wells oriented from north to south in the study area (Fig. 3), it is evident that significant variations in resistivity values exist between wells, at different depths within individual wells, and between the upper and lower sections of the same sandstone reservoir. These variations highlight the diversity and pronounced heterogeneity of the resistivity characteristics of the Lower Shihezi sandstone reservoirs in the study area.

Analysis of the factors contributing to resistivity diversification

Sedimentary environment

The depositional environment is a crucial factor contributing to reservoir heterogeneity42. The sedimentary environment in the study area transitioned from braided rivers to delta plains across the He-1 to He-3 member. The reservoir of the Lower Shihezi Formation was formed by rapid accumulation within a proximal sedimentation setting. Short-distance transportation led to variable grain sizes of the sandstone matrix carried by the river, leading to reduced reservoir homogeneity and poor sorting. Additionally, rapid sedimentation and subsequent compaction decrease the pore space and increase the complexity of the pore structure.

A petrographic analysis was performed on 100 thin sections from the Lower Shihezi Formation. The grain size distribution is predominantly medium sand (37%) and coarse sand(35%), with minor contributions from conglomerate sand (12%), conglomerate (7%), fine sand (6%), and silt (3%) (Fig. 4). This diverse grain size distribution contributes to the heterogeneity of the reservoir, leading to variations in pore diameter during sedimentation. Since resistivity is a composite response to the electrical conductivity of both the rock matrix and pore fluids, this heterogeneity also results in varied resistivity measurements. Sedimentary processes thus indirectly influence the observed resistivity diversity.

Clay mineral

In reservoirs, clay minerals are typically present in varying amounts. High clay content not only increases the Irreducible water saturation but also enhances conductivity through the cation exchange capacity of the clay minerals. The clay minerals in sedimentary rocks mainly consist of smectite, illite, kaolinite, chlorite and illite-smectite mixed layers (I/S). Generally, the cation exchange capacity of smectite, illite and I/S are relatively strong, followed by kaolinite and chlorite. Nevertheless, regardless of the type of clay mineral, as long as it is dispersed on the surface of the rock matrix particles to form a film-like distribution or is distributed in the pores in a filamentous manner to form clay bridges, a conductive network will be constituted, thereby reducing the resistivity of the reservoir.

Through the analysis of clay minerals in the study area, the average total clay content of core samples from the He-3, He-2, and He-1 Members of the Lower Shihezi Formation exhibits minimal variation, with values of 20.5%, 20.3%, and 21.1%, respectively. The clay mineral assemblage comprises I/S, illite, kaolinite, and chlorite. Specifically, in the He-3 Member, chlorite and I/S are the predominant clay minerals, with respective contents of 8.4% and 8.0%. In the He-2 Member, illite is the dominant clay mineral, accounting for 6.8%. In the He-1 Member, chlorite and kaolinite are the primary clay minerals, with proportions of 7.5% and 6.7%, respectively (Fig. 5). Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images reveal that in the study area, the I/S and illite exhibit sheet-like morphologies (Fig. 6(a),6(b)), kaolinite displays a book-page-like structure (Fig. 6(c)), and chlorite appears in both sheet-like and filamentous forms (Fig. 6(d)). These clay minerals are either dispersed around the rock matrix particles or concentrated in specific regions adjacent to them. This distribution facilitates the formation of irreducible water films, which in turn reduces the resistivity of the reservoir. Figure 7 illustrates that as the overall clay mineral content increases, there is a notable trend of decreasing resistivity. Clay minerals are predominantly found in medium to high resistivity reservoirs with resistivities exceeding 15 Ω·m, while only a minor portion occurs in low resistivity reservoirs with resistivities below 15 Ω·m. Specifically, illite and kaolinite contents are generally below 5%, whereas I/S and chlorite exhibit a broader range, varying from 1.31 to 31.6%. Overall, the presence of clay minerals in the Lower Shihezi Formation reservoirs can contribute to reduced reservoir resistivity and is one of the factors influencing resistivity variations. However, due to the relatively low correlation coefficients between clay mineral content and resistivity, they are not the primary drivers of significant changes in resistivity.

Porosity

Figure 8 illustrates the logging response characteristics of the bottom reservoir of He-3 Member of the Lower Shihezi Formation in Well X9 within the study area. The low GR values indicate the presence of sandstone reservoirs, while the negative SP anomaly suggests that the reservoir exhibits a degree of permeability. The LLD values exhibit significant variation at different depths within the reservoir, with readings of 3.9 Ω·m and 7.5 Ω·m at low-value points A and B, respectively, and 34.5 Ω·m at high-value point C. These variations suggest that the reservoir possesses pronounced heterogeneity. The T2 spectrum obtained from NMR logging exhibits a multi-peak characteristic, indicating the presence of pores with diverse diameters within the reservoir. At the depth corresponding to LLD point A, the T2 distributions for A1 and A2 are 6–12 ms and 3–6 ms, respectively. Similarly, at the depth corresponding to LLD point B, analogous T2 distribution patterns are observed. Pore space serves as the primary medium for fluid storage within the reservoir, and mutually interconnected pore spaces form an effective conductive network. Analysis of the T2 spectral peak morphologies reveals that, within the 6–12 ms range, the peaks for A1 and B1 exhibit steep profiles with large envelope areas, indicating a higher porosity associated with pore sizes in this range. In contrast, while the T2 spectral peaks for A2 and B2 within the 3–6 ms range also display steep profiles, their envelope areas are relatively smaller, suggesting a significant but lower porosity compared to the 6–12 ms pore size range.

Figure 9 presents the porosity component curves derived from the T2 spectrum of the He-3 Member of Well X9, along with their correlation coefficients with the LLD curve. Specifically, the 8 ms and 4 ms curves represent the porosity components calculated from the pore size intervals of 6–12 ms and 3–6 ms, respectively. When the values at points A and B on the LLD curve, indicated by the blue arrows, decrease, the corresponding porosity values at A1 (8 ms) and A2 (4 ms) for point A, and B1 (8 ms) and B2 (4 ms) for point B, increase, demonstrating a negative correlation. The correlation coefficients between the porosity curves of each component in the non-diameter-expanded well section and the LLD curve were systematically analyzed. Among these, the linear fitting correlation coefficients R² for the 8 ms and 4 ms component porosity curves were notably high, at 0.593 and 0.5, respectively, significantly exceeding those of other component porosity curves. This suggests that the substantial variations in reservoir resistivity are predominantly influenced by the 8 ms component porosity, with secondary influence from the 4 ms component porosity. On the corresponding T2 spectrum, the resistivity is predominantly influenced by the porosity within the 3–12 ms pore size range. Pores in this interval primarily contain capillary-bound water, and the reduction in resistivity is mainly attributed to the high conductive efficiency of micro-capillary pores. Specifically, higher porosity in this range leads to lower resistivity values. Conversely, increases in resistivity are primarily driven by the component porosity of smaller pore sizes (< 16 ms) and the elevated component porosity of medium to large pore sizes (> 32 ms). For instance, the increase in resistivity at point D in Fig. 9 is predominantly influenced by the reduction in porosity of the 4 ms and 8 ms components indicated by the green arrows, as well as the increase in porosity of the 32 ms, 64 ms, and 128 ms components highlighted by the red arrows. Similarly, the rise in resistivity at point C is primarily attributed to the significant increase in porosity of the 128 ms and 2048 ms components, as indicated by the red arrows.

Pore structure

A total of 15 pore structure parameters were derived from mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) measurements conducted on 28 core samples from six wells within the study area. These parameters include median pressure (P50), displacement pressure (Pd), mercury injection tortuosity (λi), mercury withdrawal tortuosity (λo), relative sorting coefficient (D), microscopic average coefficient (α), characteristic structure coefficient (C), maximum pore throat radius (Rmax), average pore throat radius (R), median pore throat radius (R50), structural quality index (Gg), sorting coefficient (Sp), structure coefficient (φp), skewness (Skp), and mean (DM). Correlation analysis revealed that Skp and λo exhibit relatively high correlation coefficients with LLD, at 0.25 and 0.22, respectively (Fig. 10). Skp is a parameter that quantifies the asymmetry in the distribution of pore throat sizes and exhibits a positive correlation with LLD. Higher Skp values indicate coarser pore throats and larger matrix particle diameters, which in turn lead to increased LLD. λo characterizes the tortuosity of seepage pathways formed by interconnected pores with medium-to-large pore sizes, and it exhibits a negative correlation with LLD. Specifically, higher λo indicates a more complex pore structure, leading to increased volumes of film-bound water and capillary-bound water, which in turn results in reduced reservoir resistivity43. As shown in Fig. 11, while pore structure parameters influence LLD, their impact is less significant compared to porosity within the pore size range of 3–12 ms.

Gas saturation

Theoretically, the gas-bearing characteristics of a reservoir can influence its resistivity. As gas saturation increases, the resistivity of the reservoir also tends to increase. As illustrated in Fig. 12, perforation intervals No. 1 and No. 2 correspond to high-resistivity and low-resistivity gas reservoirs, respectively. Although these intervals exhibit distinct resistivity values, other logging curves display similar variation patterns. Specifically, both intervals show low GR readings, negative anomalies in SP, increased AC, decreased DEN and CNL, and a pronounced digging effect in the CNL. These characteristics collectively indicate favorable gas-bearing properties within the reservoir. Following capacity testing, the combined daily gas production from these two Intervals was measured at 25,045 m3. At the position indicated by the red arrow in perforation interval NO. 1 of the HDIL, the ratio of the HT12 curve (representing the virgin zone resistivity) to the HT01 curve (representing the flushed zone resistivity) is 1.25. This represents the highest resistivity increase rate observed in the gas-bearing sandstone reservoir of the He-1 Member of the Lower Shihezi Formation within this well, attributable to the influence of gas content. Similarly, the position indicated by the blue arrow at the top of the perforation interval No. 2 corresponds to the lowest resistivity increase rate in the gas-bearing section, which is 1. Based on this methodology, statistical analysis was conducted on 10 wells in the study area. The resistivity increase rate in gas-bearing reservoirs ranges from 1 to 1.4. Therefore, it can be concluded that while gas saturation does contribute to an increase in formation resistivity, its overall impact on the resistivity profile remains limited, even in reservoirs with relatively high gas saturation. Gas saturation is not the predominant factor influencing formation resistivity.

Discussion

Among all the aforementioned influencing factors, porosity and pore size distribution are the primary determinants of resistivity fluctuations. Specifically, porosity within the 3–12 ms pore size range plays a critical and direct role in resistivity variations. An increase in this porosity significantly reduces reservoir resistivity. This porosity corresponds to micro-capillary pores that contain capillary-bound water but no hydrocarbons, forming a continuous and efficient conductive network. As evidenced by the NMR T2 spectrum (Fig. 8), when the content of this porosity is relatively high and other pore sizes are relatively low, resistivity reduction is most pronounced. This is primarily due to the relatively uniform pore distribution, which decreases throat tortuosity and establishes an efficient conductive pathway within the reservoir. Conversely, when this porosity decreases and large pore size porosity increases, resistivity rises. This occurs because the efficient conductive pathways formed by micro-capillary pores are disrupted, and the increase in large pore size porosity correlates with an increase in free gas or water, which disrupts the conductive network and elevates resistivity. Regarding other influencing factors, although clay minerals distributed as films, filaments, or sheets enhance reservoir conductivity, and increased reservoir heterogeneity or gas saturation reduce conductivity, these factors exert only localized effects on reservoir conductivity and are secondary contributors to resistivity fluctuations.

The formation of all these factors is fundamentally governed by the sedimentary environment within the study area. This environment not only determines lithological diversity but also leads to variations in multiple aspects, including grain size distribution, pore dimensions, and reservoir heterogeneity. Additionally, it plays a critical role in shaping the integrated effects of clay mineralogy, pore structure parameters, and gas saturation on resistivity. As a fundamental background factor, the sedimentary environment exerts a pervasive influence on all rock properties.

It is important to note that gas saturation is not the dominant factor contributing to resistivity fluctuations in the study area. This suggests that the water saturation calculation model, which is predominantly based on Archie’s equation and its derivatives, requires modification when applied to this region; otherwise, the calculated water saturation may be significantly underestimated. For instance, using the porosity within the 3–12 ms range as input instead of total porosity, or incorporating differentiated conductive weights for various pore sizes, could enhance the accuracy of the calculations. Only through such approaches can the risk of development plan failure due to calculation errors be effectively mitigated.

Conclusions

The gas-bearing tight sandstone reservoirs within the Lower Shihezi Formation in the central part of the Hangjinqi Gas Field, Ordos Basin, China, serve as a representative case for understanding resistivity fluctuations in globally analogous coarse-grained tight sandstone formations. Through this study, three factors influencing these fluctuations have been identified.

-

(1)

The rapid sedimentary environment proximal to the provenance can result in relatively coarse sandstone grain size, pronounced reservoir heterogeneity, and a wide range of pore diameters. These factors serve as the fundamental background elements influencing the fluctuation of reservoir resistivity.

-

(2)

The primary factor controlling the significant variations in resistivity is the component porosity associated with different pore sizes. Low resistivity values are predominantly influenced by the efficient conductivity of capillary-bound water pores (8 ms and 4 ms) as observed in NMR. This manifests as the envelope area within the 3–12 ms pore size range on the T2 spectrum, where a larger area indicates higher porosity, leading to a substantial decrease in resistivity. Conversely, high resistivity values are primarily attributed to larger pore size component porosity (> 32 ms, free pores) and smaller pore size component porosity (< 16 ms, clay-bound water, capillary-bound water, and some free pores). On the T2 spectrum, this is represented by the envelope areas corresponding to larger pore sizes (> 24 ms) and smaller pore sizes (< 12 ms), respectively. Specifically, higher medium-to-large pore size porosity and lower small pore size porosity result in increased resistivity.

-

(3)

The clay mineral composition, pore structure, and gas content of tight sandstone reservoirs can also influence resistivity values, resulting in minor fluctuations. However, the correlation coefficients between these factors and resistivity are relatively low, classifying them as secondary influencing factors.

Identifying the controlling factors of the significant resistivity variations in the tight sandstone gas reservoirs of the Lower Shihezi Formation within the study area is crucial for refining the current gas saturation evaluation system, which primarily relies on the classic Archie equation and its derivatives. This research can prevent the misconception that resistivity changes are predominantly influenced by gas content, thereby providing robust technical support for accurate gas saturation calculations and effective reservoir exploitation. Additionally, it offers valuable insights for the precise evaluation of tight sandstone gas reservoirs with analogous resistivity fluctuations globally.

Data availability

The authors declare that all materials and data in this paper are available, and others can replicate and build upon the authors’ published claims.The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zemanek, J. Low-resistivity hydrocarbon-bearing sand reservoirs. SPE Form. Eval. 4 (04), 515–521 (1989).

Chatterjee, R., Gupta, S. D. & Farooqui, M. Y. Application of nuclear magnetic resonance logs for evaluating low-resistivity reservoirs: a case study from the Cambay basin, India. Journal Geophys. Engineering. 9 (5), 595–610 (2012).

Mode, A. W., Anyiam, O. A. & Aghara, I. K. Identification and petrophysical evaluation of thinly bedded low-resistivity pay reservoir in the Niger Delta. Arab. J. Geosci. 8, 2217–2225 (2015).

Pratama, E., Suhaili Ismail, M. & Ridha, S. An integrated workflow to characterize and evaluate low resistivity pay and its phenomenon in a sandstone reservoir. J. Geophys. Eng. 14 (3), 513–519 (2017).

Jiang, M., Ke, S. & Kang, Z. Measurements of complex resistivity spectrum for formation evaluation. Measurement 124, 359–366 (2018).

Chunmei, L. et al. Logging-based assessment of low-resistivity oil zones: A case study from Sudan. Energy Geoscience. 4 (2), 100079 (2023).

Khalifa, M. A., Nabawy, B. S., Abu-Hashish, M. F., Al-Shareif, A. W. & Hassan, N. M. Identification of the low resistivity-low contrast (LRLC) gas-bearing pay zones in Shaly sand reservoirs using acoustic data: a case study from the Messinian Abu Madi formation, onshore nile delta, Egypt. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. Technol. 14, 2973–2993 (2024).

Bai, Z., Tan, M., Shi, Y., Li, G. & Clark, S. M. Reservoir characteristics and control mechanism of resistivity low-contrast oil pays in Chang 8 tight sandstone of Longdong West area, Ordos basin. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. Technol. 11, 2609–2620 (2021).

Hu, J. & Yan, Y. A research on the characteristics of oil and gas reservoir with low resistivity. Nat. Gas. Ind. 21 (2), 44–47 (2001).

Mu, L. X., Tian, Z. Y. & Zhao, L. M. Investigation on mechanism of low-resistivity formation of A oilfield. Acta Petrolei Sinica. 69 (2), 69–73 (2004).

Worthington, P. F. Recognition and evaluation of low-resistivity pay. Pet. Geosci. 6 (1), 77–92 (2000).

Pan, H. P., Huang, J., Fan, Z. J. & Ma, Y. Evaluation of low resistivity oil(gas)-bearing reservoirs using well logging information. Progress Explor. Geophys. 25 (6), 11–17 (2002).

Wang, Z. D. et al. Characteristics and Estimation technology of oil and gas reservoirs with low resistivity. Nat. Gas Geoscience. 19 (3), 390–395 (2008).

Wyllie, M. R. J. Log interpretation in sandstone reservoirs. Geophysics 25 (4), 748–778 (1960).

Hamada, G. M., Al-Blehed, M. S., Al-Awad, M. N. & Al-Saddique, M. A. Petrophysical evaluation of low-resistivity sandstone reservoirs with nuclear magnetic resonance log. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 29 (2), 129–138 (2001).

Salisu, A. M. et al. Impact of kaolinite and iron oxide cements on resistivity and quality of low resistivity pay sandstones. Mar. Pet. Geol. 158, 106568 (2023).

Iqbal, M. A., Salim, A. M. A., Baioumy, H., Gaafar, G. R. & Wahid, A. Identification and characterization of low resistivity low contrast zones in a clastic outcrop from sarawak, Malaysia. J. Appl. Geophys. 160, 207–217 (2019).

Mashaba, V. & Altermann, W. Calculation of water saturation in low resistivity gas reservoirs and pay-zones of the cretaceous Grudja formation, onshore Mozambique basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 67, 249–261 (2015).

Schulze, R. P., Ives, G. L., Smalley, E. A. & Smith, W. E. Evaluation of low-resistivity Simpson Series of formations. In SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, SPE-14282-MS, 22–26 (1985).

Ruhovets, V. A log analysis technique for evaluating laminated reservoirs in the Gulf Coast area. Log Anal. 31 (5), 294–303 (1990).

Coll, C., Cortiula, B., Gonzalez, G., Meza, E. & Rondon, L. Effect of vertical heterogeneities in a petrophysical evaluation of low resistivity pay zones, B sands, upper eocene, block III, lake Maracaibo. AAPG Bull. 80, 1282 (1996).

Chatterjee, R., Gupta, S. D. & Farooqui, M. Y. Application of nuclear magnetic resonance logs for evaluating low-resistivity reservoirs: a case study from the Cambay basin, India. J. Geophys. Eng. 9 (5), 595–610 (2012).

Lubis, L. A., Ghosh, D. P. & Hermana, M. Elastic and electrical properties evaluation of low resistivity pays in Malay Basin clastics reservoirs. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 38(1), 012004 (2016).

Gao, C. Q., Zhang, C. M., Bu, Z. H., Cheng, H. L. & Sun, L. F. Study of logging interpretation for low-resistivity sandstone reservoirs in Dongpu depression. Geophys. Prospectoing Petroleum. 42 (4), 550–552 (2003).

Yuan, Z. G., Chu, Z. H. & Fang, X. D. Evaluation of low resistivity oil and gas reservoirs. Special Oil Gas Reservoirs. 10 (6), 1–3 (2003).

Zhu, M. et al. Reconstruction method of the T2 water spectrum and identification of low resistivity oil layers with NMR logging while drilling. Well Logging Technol. 46 (3), 340–345 (2022).

Nie, H. et al. Sequential distribution of gas reservoirs in the Hangjinqi area, Ordos basin, North china: application of continuous and discontinuous hydrocarbon accumulation mode. Interpretation 9 (1), 91–105 (2021).

Anees, A. et al. Identification of favorable zones of gas accumulation via fault distribution and sedimentary facies: insights from Hangjinqi area, Northern Ordos basin. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 822670 (2022).

Qin, S. et al. Intragranular fractures within tight sandstone reservoirs in the Hangjinqi area, Northern Ordos basin, china: morphology, intensity and controlling factors. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 231, 212376 (2023).

Tavakoli, V., Hassani, D., Rahimpour-Bonab, H. & Mondak, A. How petrophysical heterogeneity controls the saturation calculations in carbonates, the Barremian-Aptian of the central Persian Gulf. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109568 (2022).

Nazemi, M., Tavakoli, V., Rahimpour-Bonab, H. & Sharifi-Yazdi, M. Integrating petrophysical attributes with saturation data in a geological framework, Permian-Triassic reservoirs of the central Persian Gulf. J. Afr. Earth Sc. 179, 104203 (2021).

Wang, R. et al. Clay mineral content, type, and their effects on pore throat structure and reservoir properties: insight from the permian tight sandstones in the Hangjinqi area, North Ordos basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 115, 104281 (2020).

Sun, X. et al. Diagenetic–Porosity evolution and reservoir evaluation in multiprovenance tight sandstones: insight from the lower Shihezi formation in Hangjinqi area, Northern Ordos basin. Lithosphere 13, 6411000 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. CO2 injection for enhanced gas recovery and Geo-Storage in complex tight sandstone gas reservoirs. Processes 11 (7), 2059 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Study on the seepage characteristics and influencing factors of low permeability reservoir based on microscopic seepage experiments in real sandstones-taking Dongsheng gas field in Hangjinqi area as an example. In E3S Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, 528, 01008 (2024).

Peng, Z. et al. Low-resistivity gas reservoir genesis and log evaluation method in Hangjinqi area. Nat. Gas Geoscience. 27 (11), 2054–2063 (2016).

Li, G. Q. et al. Occurrence and distribution characteristics of fluids in tight sandstone reservoirs in the Shilijiahan zone, Northern Ordos basin. Nat. Gas. Ind. 37 (2), 11–18 (2017).

Liu, L., Pan, H. P., Deng, C. X. & Huang, G. S. A method for improving permeability accuracy of tight sandstone gas reservoirs based on core data and NMR logs. Energies 12 (15), 2859 (2019).

Zhu, Z. L., Li, W. H. & Li, K. Y. The characteristic of sequence stratigraphy and sedimentary systems of Taiyuan-Xiashihezi formation in Hangjinqi area. J. Northwest. Univ. (Natural Sci. Edition). 40 (6), 1050–1054 (2010).

Cao, T. S. et al. Genesis and pore evolution of tight sandstone reservoir: taking lower Shihezi formation in the Shilijiahan block of Hangjinqi area as an example. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field. 28 (5), 598–603 (2021).

Qiu, L. W. et al. Influence of diagenesis of tight sandstone reservoir on the porosity development of lower Shihezi formation in Hangjinqi area, Ordos basin. Petroleum Geol. Recovery Effi. 26 (2), 42–50 (2019).

Davoodi, S., Shad, S. A. & Tavakoli, V. A fresh look at the Lucia classification using mud-and grain-dominated reservoirs of the Persian Gulf. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 232, 212437 (2024).

He, S. W., Li, A. R., Wang, S., Liu, H. & Mao, G. L. Studies on the influencing mechanisms of pore structures on resistivities. Petroleum Geol. Oilfield Dev. Daqing. 31 (1), 172–174 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Nature Science Foundation of Shanxi Province (No. 202203021211288, No. 202303021212310), National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 42404097) and the Scientific and Technologial Innovation Programs of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi (No. 2021L585, No. 2023L388). We also acknowledge the editors and reviewers for their constructive suggestions and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L. and G.S.H. wrote the main manuscript, H.D. and S.Y.M. provided technical guidance for the writing of the manuscript, and G.Q.L. provided comprehensive logging data from ten wells. All authors reviewed and consented to the publication of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Huang, G., Ding, H. et al. Analysis of the controlling factors of resistivity fluctuations in tight sandstone reservoirs of the Hangjinqi gas field, Ordos basin. Sci Rep 15, 22383 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06236-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06236-x