Abstract

Water scarcity, driven by climate change and increased drying trends in the Mediterranean region, presents severe water availability and agricultural production shortages, particularly in North Africa. Morocco, a country with arid to semi-arid conditions, is facing a growing water demand, exacerbated by extreme climatic events such as droughts and inefficient water management. The agricultural sector, the country’s major water consumer, is a pillar of Morocco’s economy. Public policy in the sector has increased irrigated surfaces, contributing to a severe water resources shortage. This study utilizes satellite-based radar data to evaluate the spatial extent and status of Moroccan dams from 2018 to 2024. By focusing on significant reservoirs, particularly the Al Massira dam in the Oum Er-Rbia basin, this investigation aims to assess changes in surface water area and analyze the underlying factors contributing to these variations. Satellite radar data offers a cost-effective and reliable method for monitoring water level changes across large surface areas, compensating for the scarcity of in-situ measurements. The study’s findings reveal an apparent decrease in surface water areas across Moroccan reservoirs, with significant declines observed between 2021 and 2023. Al Massira dam, in particular, experienced severe declines in water storage, dropping to less than 3% of its capacity since 2023. This decline is attributed to ongoing drought conditions, which have persisted since 2017, and unsustainable water extraction driven by the expansion of water-intensive crops under national agricultural policies such as the Green Morocco Plan (GMP). Regional disparities in water availability were also highlighted. While southern reservoirs experienced drastic reductions, northern reservoirs exhibited more stable water levels, reflecting the heterogeneous impact of climatic variability and, thus, precipitation patterns across the country. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of radar data in monitoring dam water levels and underscore the urgent need for improved water management strategies, particularly in Morocco’s central and southern regions, which rely heavily on reservoirs for agricultural and drinking water supplies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change and increasing drying trends in the Mediterranean region are intensifying water scarcity, threatening both drinking water availability and agricultural production, and thus jeopardizing regional food security and social stability1,2,3,4. Identified as a climate hotspot, the Mediterranean basin is facing an increase in water demand, further underlining the ever-growing relevance of water-related issues5,6,7. This is especially critical for North African countries, where it is exacerbated by the region’s arid climate, rapid population growth, and inefficient water management practices8,9,10,11. This shortage has an impact not only on irrigation water supplies but, most notably, on drinking water requirements, especially in southern Mediterranean countries12,13,14,15.

Additionally, the increased frequency and severity of extreme climatic events, particularly droughts, has further accentuated the discrepancy between water availability and demand over both space and time scales4,16,17. This growing imbalance presents significant challenges in ensuring reliable access to water and food18,19. While climate variability is a clear factor influencing water storage, human activities, particularly irrigation, are becoming increasingly decisive12,15,20. For instance, Morocco’s agricultural sector accounts for 88% of the country’s water consumption, whereas the primary sources of water are streams, large reservoirs, seasonal snowmelt, and groundwater aquifers11,21,22,23,24,25.

Throughout seasonal peak irrigation periods, water flows from major basins are often insufficient11,26,27. To overcome this issue, Moroccan policymakers have implemented a dam-building strategy aimed at improving regulation and optimizing water management, ultimately enhancing water supplies in Morocco and thereby improving agricultural yields28. However, large-scale anthropogenic interventions have consequences. Activities such as land-use changes, dam and reservoir construction, and large-scale surface and groundwater withdrawals have been shown to have adverse effects on downstream river basins29,30,31. These activities also exacerbated imbalances between mountainous and lowland regions. While dam construction offers advantages in Morocco, it also presents significant challenges32,33. For instance, the construction of dams has led to communities relocating their settlements and ecosystems deteriorating34 as a result of reduced groundwater recharge.

Although the water stored in these dams and reservoirs is mainly devoted to drinking water, the agricultural sector gets the lion’s share. Indeed, it contributes almost 15% to Morocco’s GDP and employs around 45% of the economic manpower, most of whom are represented in rural communities. Climate change continues to cause more frequent and intense droughts worldwide7,35. Especially in the Mediterranean region, including Morocco, the climate projections suggest more frequent hot days, an increase in air temperature, and a decrease in precipitation amount36,37,38,39. Morocco is already considered under water stress with only 500 cubic meters of freshwater per capita per year, compared to 2500 cubic meters in 196040,41,42,43. Thus, Morocco is expected to reach an extremely high level of water stress by 204044. Therefore, it becomes even more critical for Morocco to manage its water resources effectively to ensure food security and sustain its agricultural sector45.

Monitoring the evolution of reservoirs is challenging due to the large surface area that needs to be covered46. This makes it an expensive task due to the cost of purchasing, installing, and monitoring all the necessary sensors required to cover a large surface47,48. In-situ measurements are essential for understanding the dynamics of water bodies; however, the cost and difficulty of accessing reliable information on water bodies make it challenging for both the scientific and stakeholder communities49,50.

Understanding the status of reservoirs, both in terms of surface area and volume, is vital for comprehensive analyses of water resources, as well as the broader hydrological and ecological implications51,52,53. While the significance of dams is widely acknowledged, comprehensive data on their evolution is often limited due to varied financial constraints54,55,56. To our knowledge, a detailed assessment of dam evolution, specifically focusing on large reservoirs in Morocco, remains to be undertaken. To address these issues, earth observation has become an increasingly effective method for monitoring water bodies57,58. This technique has been widely used to examine various continental water bodies, including lakes and reservoirs59. It has provided valuable insights into the water extension60 and water quality61. Moreover, satellite radar has become a more reliable and accurate instrument for determining the elevation of open water bodies62.

Given this background, the primary objectives of the present study are to utilize remotely sensed radar data to evaluate the spatial extent and status of dam water levels. In pursuit of this overarching goal, we have defined two specific objectives: i) mapping the water extent using satellite imagery; ii) considering all Moroccan dams operating at volumes equal to or above 100 Mm3, then focusing on the country’s second-largest dam, the Al Massira dam which is located in the Oum Er-Rabia basin; and iii) further discussing the underlying reasons for the observed changes in water extent.

Material and method

Study area

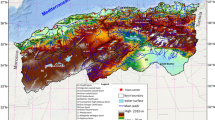

As a North African country, Morocco is situated in the southwestern Mediterranean region, Where It stands out with its diverse geography and climate63,64. It is well known for its dam strategy, which is crucial in water resource management and supports the country’s socio-economic development27,65. These dams serve multiple purposes, including domestic water supply, agricultural irrigation, industrial needs, and hydropower generation33,66. The construction of big reservoirs in Morocco has significantly contributed to storing and managing water resources, especially in arid and semi-arid regions67. These reservoirs act as strategic water reserves, helping to mitigate the impacts of water scarcity and droughts, which are common in the country. They provide a reliable and consistent water supply, supporting agricultural productivity and reducing dependence on rainfall for irrigation.

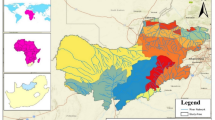

The present study examines all of Morocco’s dams with volumes equal to or above 100 Mm3. It focuses on the country’s second-largest dam, the Al Massira Dam, in the Oum Er-Rabia basin (Fig. 1).

Methodology

Sentinel-1 imagery was selected because it can penetrate cloud cover and provide reliable data under all weather conditions. This makes it ideal for continuous monitoring in regions with frequent cloud cover (35% to 50% of Sentinel-2 images covering Morocco have a cloud presence, depending on the region). The Sentinel-1 imagery was pre-processed through steps to ensure data quality and consistency. First, thermal noise was removed from the images to eliminate any artificial signals that could interfere with the analysis. Following this, radiometric calibration was performed, converting the backscatter values to sigma nought (σ⁰) to maintain consistency in reflectivity measurements68. A Lee filter was applied to address the inherent speckle noise in SAR data69, which enhanced the interpretability of the imagery. The next step involved geometric correction, where the images were terrain-corrected using a Digital Elevation Model (Copernicus DEM) to account for distortions caused by topography, thereby ensuring accurate geo-referencing70. Finally, the data were resampled to a standard grid, typically at a 20-m resolution, to enable consistent analysis across the dataset.

Three methods were compared to extract water bodies from the pre-processed Sentinel-1 images. First, thresholding was employed, where a fixed threshold was applied to the backscatter values (σ⁰) to distinguish between water and non-water pixels. The threshold value was determined through an iterative optimization process using histogram analysis of Sentinel-1 backscatter values for water and non-water pixels. Multiple threshold values were tested (0.01 increment), and -18.34 was identified as the optimal cutoff based on the best separation between water and non-water classes. This selection was further validated by comparing extracted water bodies with manually digitized reservoir boundaries from high-resolution Pleiades images, ensuring consistency and accuracy in water delineation. Second, a Support Vector Machine (SVM) and a Random Forest classifier were trained using labeled training data representing water and non-water classes. This classifier was then applied to the imagery to generate a map of water extent . The performance of this classifier was compared with that of the other two methods (Fig. 2).

To validate the accuracy of the extracted water bodies, we manually digitized reservoir boundaries from high-resolution Pleiades images (2.8 m of spatial resolution at multispectral bands) acquired over nine regions. These manually delineated boundaries served as reference data for independent validation. The evaluation included a comparison between the extracted water extent from Sentinel-1 and the digitized Pleiades reference data, ensuring a robust assessment of accuracy . The accuracy of each method was measured using the Kappa coefficient, overall accuracy, and confusion matrices. Random Forest consistently outperformed the other techniques in these evaluations, leading to its selection for subsequent analysis. Indeed, the Random Forest classifier was ultimately selected as the primary method due to its superior performance, which was measured by the Kappa statistic (≥ 0.95). In comparison, the Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier and the thresholding method achieved Kappa values of 0.92 and 0.91, respectively.

Similar studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of using SAR data combined with machine learning for surface water mapping. For example59, successfully applied Random Forest and other classifiers to Sentinel-1 imagery for delineating water bodies in different regions of the world, highlighting the robustness of these methods in remote sensing applications. Sentinel-1 images were chosen for this study due to their high temporal resolution and sensitivity to water extent, which are critical for capturing dynamic changes in water extent over time71. This consistent temporal and spatial coverage enhance the reliability of trend analyses, such as those performed using Sen’s slope72, to robustly quantify the rate of change in water extent.

Moreover, to analyze the trends in water extent, we also computed trends in meteorological data from the ERA5-Land reanalysis dataset73. The generated water extent maps were compared with this hydro-meteorological data, specifically focusing on climatic factors such as precipitation and temperature. This comparative analysis provided valuable insights into how changes in these climatic variables influence water body dynamics. By examining the trends in both water extent and meteorological data, we gain a better understanding of the effects of climate conditions and the observed fluctuations in water bodies (Fig. 2).

Results and discussion

Water extension in the main reservoirs

The temporal dynamics of the surface area of selected reservoirs in Morocco, spanning from July 2018 to January 2024, reveal significant variations (Fig. 3). Al Wahda reservoir, situated in the north, shows a relatively stable yet slightly declining trend, maintaining comparatively higher water levels throughout the observation period. Conversely, reservoirs located in central and southern Morocco, such as Al Massira and Mansour Eddahbi, exhibit a more pronounced decline in water surface area, particularly noticeable from mid-2021 to early 2024 (Fig. 3).

However, in the following years, there was a noticeable and steady decline in surface area, resulting in a severe reduction in water extent . The sharp decrease between 2021 and 2023 is particularly striking, likely reflecting the impact of successive droughts.

The analysis is further refined by Sen’s slope, which represents the percentage change in the water extent over time relative to the initial surface (Fig. 4). The graphic clearly illustrates the contrast between trends in most reservoirs. Whereas dams with a positive Sen slope, such as Hassan II and Sidi Chahed, show an increase in water extent over time, which suggests that conditions in these areas continue to benefit from stable or even improving hydrological resources, dams with a positive Sen slope, such as Hassan II and Sidi Chahed, show an increase in water extent over time, which suggests that these areas continue to benefit from stable or improving hydrological resources37. These dams are mainly located in northern Morocco. On the other hand, dams with significantly negative Sen slopes, such as Al Massira and Bin El Ouidane, reveal a substantial decrease in water extent, highlighting that these regions have experienced and continue to have a substantially reduced water supply.

Explaining the changes: climatic variability

Analyzing precipitation patterns in northern Morocco from 1980 to 2023, as shown in Fig. 5A, reveals significant trends with important implications for water resource management and drought mitigation in the region. Total annual precipitation is presented over the years in Fig. 5A, highlighting in red years where precipitation amounts dropped below the 25th percentile (first quartile). The overall trend, indicated by the black line, shows a steady decline in annual precipitation with a slope of -7.77 mm per decade. Reduced precipitation implies a progressive long-term decrease in water availability11,36, thus exacerbating the region’s vulnerability to droughts and severe water shortages.

The first evident consequence of the decreasing precipitation trend is the reduction in reservoir surface area across Morocco from April 2018 to June 2024, as illustrated in Fig. 5A. The problem extends beyond water volumes; the timing of water availability is becoming a critical concern. The rainy season plays a decisive role in replenishing reservoirs, and yet it is becoming increasingly unpredictable. At the same time, increasing temperatures are leading to excessive snowmelt in the Atlas Mountains, a vital source of water for the reservoirs, disrupting the steady year-round stream flow needed to meet the region’s growing agricultural requirements and replenish dams6,37,38. Indeed, the straightforward correlation between reduced precipitation and reservoir area retraction highlights the tight correlation between climate change and the hydrological water balance, stressing the impacts of lower precipitation on water availability in the region.

Moreover, numerous studies have already established that global warming is exacerbating the water cycle, thus affecting the worldwide precipitation distribution74. Even the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) emphasizes that average precipitation in semi-arid and arid regions tends to decrease by around 0.3% per decade (in Morocco’s case, this rate has been around 2.59%)75. Partly due to its geographical location in a hotspot of the Mediterranean Basin, Morocco has been significantly affected by global warming. This has been supported over time by data from the ERA5 reanalysis, which has shown that most parts of Morocco have experienced a substantial decline in precipitation and a noticeable increase in temperature. In many regions, these trends are leading to growing pressure on water resources, as shown in Fig. 5A .

In addition, the Z-score was used to identify dry periods for the precipitation time series between 1981 and 2023. The results reveal an alternation between dry and wet periods, starting with a drought from 1981 to 1986. From 1987 to 1989, the Z-score was relatively weak, ranging between 0.75 and 2.5. Then, a second dry period from 1990 to 1995, followed by a very short but wet 1996, with the dry period continuing until 2001. From 2002 to 2007, the conditions were slightly mixed, with a dry trend in some southern basins and a somewhat wet pattern in northern basins. While 2008 started with neutral values for the central Moroccan basins and wet conditions for the south and north basins, this was followed by the wettest year in Morocco’s recorded climatic history in 2009, especially for the northern basins, with a Z-score exceeding 3; this period lasted until 2014. Following the wettest year, the country experienced one of the most prolonged dry periods from 2015 onwards, except for 2018, which was relatively damp and has continued to intensify with increasing severity across the country (Fig. 5B).

Al Massira reservoir: on the brink of collapse

Here, Al Massira has been selected for an in-depth analysis, as it is one of Morocco’s largest reservoirs and has witnessed the most drastic reduction in water extent, as shown in the lower-left plot of Fig. 6. The images highlight the dramatic decrease in water extent over time, with a significant decline observed particularly after 2020, as indicated by the diminishing cyan-colored areas representing water. This visual evidence underscores the critical water scarcity issues faced by the region, with Al Massira approaching critically low levels of water storage, reaching 3% as recorded by water resources agencies. Furthermore, based on data provided by the water ministry in early 2024, it was revealed that by August 2024, Al Massira had been operating at barely around 1% of its capacity, thereby being almost completely depleted. Even this formerly extensive reservoir has become a relative shadow, which underlines the severity of the region’s water crisis.

Although evaporation accounts partly for water loss in the Al Massira dam, it can never be considered an exclusive factor. With 80% of Morocco’s irrigated land in the Oum Er-Rabia region, Al Massira is essential for irrigating the extensive agricultural areas. During the agricultural growing season, significant volumes of water are diverted from the reservoir to sustain crop development. Indeed, the Green Morocco Plan (GMP) emphasizes the importance of utilizing water from reservoirs throughout Morocco to support the expansion of agricultural practices76. However, the rapid expansion has put even tighter pressure on water resources.

The GMP represents a major initiative to promote Moroccan agricultural development and modernization through two significant pillars: promoting competitive, large-scale farming and supporting smallholder farmers in marginal regions. The plan aimed to mobilize 147 billion dirhams over 12 years, with 75 billion dirhams allocated to modern agriculture (Pillar 1) and 20 billion dirhams for solidarity agriculture (Pillar 2)77. Pillar 1 focused on high-value crops, mainly represented by citrus, olives, and vegetables, while Pillar 2 targeted poverty alluviation, especially among communities in rural areas. Around 40% of the investment has been presented as governmental subsidies, focusing on increasing agricultural productivity, primarily through the expansion of drip irrigation areas, which increased from 155,000 hectares in 2008 to 700,000 hectares by 2020. Although agricultural development has contributed relatively to employment and GDP growth, it has also led to regional disparities and environmental concerns, particularly regarding water overexploitation, with annual water withdrawals exceeding the renewable supply (Kmoch et al., 2024; Asedrem, 2021). Despite the increased investment, small-scale farmers and rural communities received limited benefits, thus highlighting issues concerning the long-term viability of the results achieved as part of this program78. This highlights the vital need to balance increased agricultural production with the preservation of critical water resources79. Indeed, it is a delicate interplay between ensuring food security and maintaining ecological balance, a challenge that Morocco, like many arid and semi-arid regions, grapples with in the face of climate change and increasing population demand80. For instance, Casablanca, Morocco’s largest city, relies on the Al Massira dam as its primary drinking water supplier. However, the reservoir has significantly reduced over the past seven years.

Explaining the changes: expanding agriculture

Morocco has increasingly shifted towards growing water-intensive crops, such as olives, citrus fruits, avocados, and tomatoes (Fig. 7)11,80 . This shift is exacerbating the country’s already severe water issues. The expansion of agricultural areas is striking, with avocado production increasing more than fivefold from 2000 to 2024 (Fig. 7). Each crop requires between 1,000 and 1,300 mm of water to grow (ref). Citrus fruit production has also doubled, requiring 900 to 1,200 mm of water. For example, orange production jumped from 870,000 tons in 2000 to over 1.2 million tons in 2022. Tomatoes, including cherry tomatoes, have also shown a significant increase in production, as revealed by FAO data (Fig. 7). These increases are primarily due to government policies that encourage the export of high-value crops, making Morocco a key exporter to international markets. However, while Morocco exports these water-intensive crops, it still has to import a significant amount of staple foods because domestic production is unstable80.

The Oum Er-Rabia region exemplifies Morocco’s challenges in balancing agricultural demands with limited water resources. Despite receiving an average annual precipitation of 360 mm, the region’s farms require substantial water for irrigation, particularly for water-intensive crops. This highlights the challenge of cultivating such crops in a country with limited water resources. For instance, wheat, which requires significantly less water, illustrates this more general issue, given that wheat is a staple component of the Moroccan diet, consumed daily in the form of bread. Its production fluctuates significantly in response to rainfall, resulting in substantial drops in wheat yields, which forces Morocco to increase imports to meet demand (Fig. 7). This dependence on rainfall makes wheat production critical and uncertain within Morocco’s agricultural system. Future investigations could integrate hydrological and evapotranspiration models to quantitatively assess the exact contribution of agriculture to water depletion, offering a more detailed understanding and thus aiding in the formulation of sustainable water management practices81.

The government’s commitment to intensive agriculture relies on sufficient water supplies from both surface and groundwater sources. The government plan was based on the availability of approximately 18 billion cubic meters of water. Still, due to persistent droughts, this quantity has drastically decreased, particularly in light of the agricultural sector’s significant contribution to economic growth80. However, these policies exacerbate imbalances and further deplete groundwater reserves, thus underpinning local market instability. While insufficient progress has been made regarding groundwater preservation and management, a considerable gap remains between communities with reliable access to water and those without such access to groundwater. This again highlights the pressing need for sustainable water management to align with Morocco’s agricultural demands.

Towards action: the need for more outstanding efforts

The current state of Moroccan reservoirs is highly alarming, with water levels declining significantly. This situation is being exacerbated for surface and groundwater by excessive water abstraction to satisfy the growing agricultural demand. Consequently, groundwater levels nationwide are dropping significantly. For instance, in the Mejjat region of the Haouz plain, located in the Tensift basin, excessive groundwater withdrawal has led to a decline in groundwater levels reaching up to 5 m per year since 201611. Moreover, in several regions, the water table has declined by up to 50 m between 1980 and 202111. These combined water scarcities require immediate intervention. Considering these challenges, it is imperative to reassess current policies and practices, particularly in water-dependent regions.

Additionally, promoting efficient irrigation practices and techniques, such as drip irrigation, and encouraging crop diversification can help optimize water usage and reduce strain on the already diminishing water reserves. Furthermore, a comprehensive water management strategy should prioritize conservation measures and explore alternative water sources. This includes investing in water recycling and desalination projects and implementing strict water conservation policies at the individual community levels.

To support these efforts, robust monitoring systems and data collection initiatives should be established to continually assess water availability, usage, and the impact of conservation measures. This data-driven approach will provide stakeholders and policymakers with valuable insights to inform their decisions and implement effective water management strategies. Moreover, supporting small family farms could have been crucial for socio-economic development, promoting food sovereignty, and more efficient water use. However, economic and political interests have driven the Moroccan state to prioritize large-scale commercial agriculture instead.

Conclusion

The present study reveals the critical status of surface water areas in Moroccan reservoirs from 2018 to 2024. A specific decrease was observed between 2021 and 2023, attributed to the ongoing drought in Morocco that began in 2017. The overall trend is heavily influenced by reduced precipitation and climatic variability, with an average annual precipitation decline of 7.77 mm per decade exacerbating water shortages across the country. The analysis of Sen’s slope highlights regional disparities, with certain reservoirs, Al Massira and Bin El Ouidane, experiencing severe reductions. In contrast, others in northern Morocco, such as Hassan II and Sidi Chahed, showed more stable water resources.

Additionally, the expansion of water-intensive crops, driven by government policies, has further exacerbated the status of water resources, particularly in central and southern regions, which rely on reservoirs for both agriculture and drinking water supply. The situation is especially critical for reservoirs such as Al Massira, which has approached severe water storage levels (less than 3% since 2023), primarily due to the combined effects of reduced precipitation and over-extraction for irrigation. This reflects broader national concerns, as the expansion of agriculture, particularly under the Green Morocco Plan, has led to unsustainable water use. The growing water demand from agriculture, combined with ineffective water management strategies, is depleting both surface and groundwater resources, deepening Morocco’s water crisis.

Similar water crisis issues have been observed worldwide, including in Chile, India, and the USA (30, 31). In Chile, the overextraction of groundwater for agricultural use in the Atacama Desert has raised concerns about long-term sustainability. Meanwhile, states like California have faced severe droughts in the USA, leading to strict water conservation measures and debates over water rights. These crises highlight the global challenge of balancing agricultural needs with sustainable water management. Addressing these challenges requires a balanced approach that reconciles agricultural expansion with the preservation of water resources. There is a critical need for more efficient water use, promoting efficient irrigation practices and crop diversification, as well as expanding alternative water sources, such as desalination. Ultimately, a comprehensive, data-driven water management strategy is essential to mitigate the impacts of climate change, ensure economic development, and achieve long-term water security in Morocco’s semi-arid regions.

While this study spans 2018–2024, future research would benefit from extending this timeframe to capture long-term trends and the cumulative impacts of climate change and agricultural policies. This could be achieved by integrating additional satellite datasets, such as Landsat, with its historical archive dating back to the 1980s, or MODIS, which offers high temporal resolution data ideal for analyzing long-term water dynamics and climate variability. Platforms like Google Earth Engine (GEE) can facilitate the processing of these large-scale datasets. For instance82, demonstrated how GEE’s JavaScript API significantly enhances surface water dynamics monitoring in drought-prone Mediterranean regions. Similarly83, highlighted the value of remote sensing in evaluating three decades of land-use and land-cover changes in the Ziz Oases, an environmentally vulnerable region in Morocco’s Pre-Saharan area.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to their storage on the EO-Africa (ESA) servers, where the work was conducted in 2023. The corresponding author no longer has access to the server or the intermediate (processed) data. However, the native data used in the study are publicly accessible and can be found at: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/explore-data/data-collections.

References

Essa, Y. H., Hirschi, M., Thiery, W., El-Kenawy, A. M. & Yang, C. Drought characteristics in Mediterranean under future climate change. npj Climate Atmos. Sci. 6(1), 133 (2023).

Stathi, E., Kastridis, A. & Myronidis, D. Analysis of hydrometeorological trends and drought severity in water-demanding Mediterranean islands under climate change conditions. Climate 11(5), 106 (2023).

Padhiary, J., Patra, K. C. & Dash, S. S. A novel approach to identify the characteristics of drought under future climate change scenario. Water Resour. Manage 36(13), 5163–5189 (2022).

Oussaoui, S. et al. Mapping drought severity impact on arboriculture systems over Tadla and lower Tassaout plains in Morocco using Sentinel-2 data and machine learning approaches. Geocarto Int. 40(1), 2471104 (2025).

Solans, M. A., Macian-Sorribes, H., Martínez-Capel, F. & Pulido-Velazquez, M. Vulnerability assessment for climate adaptation planning in a Mediterranean basin. Hydrol. Sci. J. 69(1), 21–45 (2024).

Tuel, A. & Eltahir, E. A. Seasonal precipitation forecast over Morocco. Water Resour. Res. 54(11), 9118–9130 (2018).

Cook, B. I., Mankin, J. S. & Anchukaitis, K. J. Climate change and drought: From past to future. Curr. Climate Change Rep. 4, 164–179 (2018).

Tanarhte, M. et al. Severe droughts in North Africa: A review of drivers, impacts and management. Earth Sci. Rev. 250, 104701 (2024).

Hadri, A. et al. Spatio-temporal analysis of meteorological drought return periods in a Mediterranean arid region, the center of Morocco. J. Water Climate Change 15(9), 4573–4595 (2024).

Amazirh, A. et al. Drought cascade lag time estimation across Africa based on remote sensing of hydrological cycle components. Adv. Water Resour. 182, 104586 (2023).

Ouassanouan, Y. et al. Multi-decadal analysis of water resources and agricultural change in a Mediterranean semiarid irrigated piedmont under water scarcity and human interaction. Sci. Total Environ. 834, 155328 (2022).

Claro, A. M., Fonseca, A., Fraga, H. & Santos, J. A. Future agricultural water availability in Mediterranean Countries under climate change: A systematic review. Water 16(17), 2484 (2024).

Rocha, J. et al. Impacts of climate change on reservoir water availability, quality and irrigation needs in a water scarce Mediterranean region (southern Portugal). Sci. Total Environ. 736, 139477 (2020).

Mancuso, G., Lavrnić, S. & Toscano, A. Reclaimed water to face agricultural water scarcity in the Mediterranean area: An overview using sustainable development goals preliminary data. Adv. Chem. Pollut. Environ. Manag. Protect. 5, 113–143 (2020).

Hamdy, A., & Lacirignola, C. (2005). Coping with water scarcity in the Mediterranean: what, why and how. CIHEAM. Mediterranean Agronomic Institute. Bari, Italy, 277–326.

Seneviratne, S. I., Zhang, X., Adnan, M., Badi, W., Dereczynski, C., Luca, A. D., Ghosh, S., Iskandar, I., Kossin, J., Lewis, S., & Otto, F. Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate.

Sánchez, E. et al. Future climate extreme events in the Mediterranean simulated by a regional climate model: A first approach. Global Planet. Change 44(1–4), 163–180 (2004).

Saladini, F. et al. Linking the water-energy-food nexus and sustainable development indicators for the Mediterranean region. Ecol. Ind. 91, 689–697 (2018).

Iglesias, A., Garrote, L., Diz, A., Schlickenrieder, J. & Martin-Carrasco, F. Re-thinking water policy priorities in the Mediterranean region in view of climate change. Environ. Sci. Policy 14(7), 744–757 (2011).

Wada, Y. et al. Global monthly water stress: Water demand and severity of water stress. Water Resour. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009792 (2011).

Kahime, K., Boussakouran, A., El Hidan, M. A., & El Yamani, M. (2024). Exploring Climate Change: Morocco in Focus. Climate Change Effects and Sustainability Needs: The Case of Morocco, 3–20.

Rhoujjati, N. et al. Snowpack and groundwater recharge in the Atlas mountains: New evidence and key drivers. J. Hydrol.: Reg. Stud. 49, 101520 (2023).

Hanich, L. et al. Snow hydrology in the Moroccan atlas mountains. J. Hydrol.: Reg. Stud. 42, 101101 (2022).

Baba, M. W., Gascoin, S., Jarlan, L., Simonneaux, V. & Hanich, L. Variations of the snow water equivalent in the Ourika catchment (Morocco) over 2000–2018 using downscaled MERRA-2 data. Water 10(9), 1120 (2018).

Bouimouass, H., Fakir, Y., Tweed, S. & Leblanc, M. Groundwater recharge sources in semiarid irrigated mountain fronts. Hydrol. Process. 34(7), 1598–1615 (2020).

Kharrou, M. H. et al. Assessing irrigation water use with remote sensing-based soil water balance at an irrigation scheme level in a semi-arid region of Morocco. Remote Sens. 13(6), 1133 (2021).

Jarlan, L. et al. Remote sensing of water resources in semi-arid Mediterranean areas: The joint international laboratory TREMA. Int. J. Remote Sens. 36(19–20), 4879–4917 (2015).

Tahiri, A. Z. The four misses of agricultural water husbandry in the Maghreb. World Water Policy 10(3), 623–648 (2024).

Ekka, A., Pande, S., Jiang, Y. & der Zaag, P. V. Anthropogenic modifications and river ecosystem services: A landscape perspective. Water 12(10), 2706 (2020).

Romero, E. et al. Long-term water quality in the lower Seine: Lessons learned over 4 decades of monitoring. Environ. Sci. Policy 58, 141–154 (2016).

Grantham, T. E. Use of hydraulic modelling to assess passage flow connectivity for salmon in streams. River Res. Appl. 29(2), 250–267 (2013).

Vinci, G. et al. The health of the water planet: Challenges and opportunities in the Mediterranean area an overview. Earth 2(4), 894–919 (2021).

Ait Kadi, M., & Ziyad, A. (2018). Integrated water resources management in Morocco. In Global Water Security: Lessons Learnt and Long-Term Implications (pp. 143–163).

Bernis-Fonteneau, A. et al. Farmers’ variety naming and crop varietal diversity of two cereal and three legume species in the Moroccan High Atlas using DATAR. Sustainability 15(13), 10411 (2023).

Mukherjee, S., Mishra, A. & Trenberth, K. E. Climate change and drought: A perspective on drought indices. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4, 145–163 (2018).

Tuel, A., Kang, S. & Eltahir, E. A. Understanding climate change over the southwestern Mediterranean using high-resolution simulations. Clim. Dyn. 56(3), 985–1001 (2021).

El Moçayd, N., Kang, S. & Eltahir, E. A. Climate change impacts on the Water Highway project in Morocco. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24(3), 1467–1483 (2020).

Driouech, F., ElRhaz, K., Moufouma-Okia, W., Arjdal, K. & Balhane, S. Assessing future changes of climate extreme events in the CORDEX-MENA region using regional climate model ALADIN-climate. Earth Syst. Environ. 4(3), 477–492 (2020).

Marchane, A., Tramblay, Y., Hanich, L., Ruelland, D. & Jarlan, L. Climate change impacts on surface water resources in the Rheraya catchment (High Atlas, Morocco). Hydrol. Sci. J. 62(6), 979–995 (2017).

Bleu, P. (2019). State of the Environment and Development 2019: Preliminary version of Chapter 6: Food and water security.

Suárez-Varela, M., Blanco Gutierrez, I., Varela-Ortega, C., Esteve, P., Jaouani, A., Gafrej, R., ... & Ker Rault, P. (2018). Review of the use of economic instruments in water management in Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia.

Shahin, M. (2007). Water resources and hydrometeorology of the Arab region (Vol. 59). Springer Science & Business Media.

Khater, A. R. Intensive groundwater use in the Middle East and North Africa. Population 103(1950), 2000–2025 (1975).

UNICEF. (2008). Water scarcity: Addressing the growing lack of available water to meet children’s needs. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/wash/water-scarcity [Online; accessed 16-Jan-2023].

Seif-Ennasr, M. et al. Climate change and adaptive water management measures in Chtouka Aït Baha region (Morocco). Sci. Total Environ. 573, 862–875 (2016).

García-Ruiz, J. M. et al. Mediterranean water resources in a global change scenario. Earth-Sci. Rev. 105(3–4), 121–139 (2011).

Morawska, L. et al. Applications of low-cost sensing technologies for air quality monitoring and exposure assessment: How far have they gone?. Environ. Int. 116, 286–297 (2018).

Ayaz, M., Ammad-Uddin, M. & Baig, I. Wireless sensor’s civil applications, prototypes, and future integration possibilities: a review. IEEE Sens. J. 18(1), 4–30 (2017).

Wang, Z. A. et al. Advancing observation of ocean biogeochemistry, biology, and ecosystems with cost-effective in situ sensing technologies. Front. Marine Sci. 6, 519 (2019).

Andres, L., Boateng, K., Borja-Vega, C. & Thomas, E. A review of in-situ and remote sensing technologies to monitor water and sanitation interventions. Water 10(6), 756 (2018).

Yang, D., Yang, Y. & Xia, J. Hydrological cycle and water resources in a changing world: A review. Geogr. Sustain. 2(2), 115–122 (2021).

Dang, T. D., Chowdhury, A. K. & Galelli, S. On the representation of water reservoir storage and operations in large-scale hydrological models: Implications on model parameterization and climate change impact assessments. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24(1), 397–416 (2020).

Habets, F., Molénat, J., Carluer, N., Douez, O. & Leenhardt, D. The cumulative impacts of small reservoirs on hydrology: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 643, 850–867 (2018).

Moran, E. F., Lopez, M. C., Moore, N., Müller, N. & Hyndman, D. W. Sustainable hydropower in the 21st century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115(47), 11891–11898 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Hydrological cycle in the Heihe River Basin and its implication for water resource management in endorheic basins. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 123(2), 890–914 (2018).

Piton, G. et al. Why do we build check dams in Alpine streams? An historical perspective from the French experience. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 42(1), 91–108 (2017).

McCabe, M. F. et al. The future of Earth observation in hydrology. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21(7), 3879–3914 (2017).

Liu, R., Xie, T., Wang, Q. & Li, H. Space-earth based integrated monitoring system for water environment. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2, 1307–1314 (2010).

Tottrup, C. et al. Surface water dynamics from space: A round robin intercomparison of using optical and SAR high-resolution satellite observations for regional surface water detection. Remote Sens. 14(10), 2410 (2022).

Chen, Z. & Zhao, S. Automatic monitoring of surface water dynamics using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data with Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 113, 103010 (2022).

Soomets, T. et al. Validation and comparison of water quality products in Baltic lakes using Sentinel-2 MSI and Sentinel-3 OLCI data. Sensors 20(3), 742 (2020).

Yao, F. et al. Satellites reveal widespread decline in global lake water storage. Science 380(6646), 743–749 (2023).

García-Herrera, R., & Barriopedro, D. (2018). Climate of the Mediterranean region. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science.

Allen, H. Mediterranean ecogeography (Routledge, 2014).

Chehbouni, A. et al. An integrated modelling and remote sensing approach for hydrological study in arid and semi-arid regions: The SUDMED Programme. Int. J. Remote Sens. 29(17–18), 5161–5181 (2008).

Alaoui, M. Water sector in Morocco: Situation and perspectives. Water Resour. Ocean Sci. 2(5), 108–114 (2013).

Moumen, Z., El Idrissi, N. E. A., Tvaronavičienė, M. & Lahrach, A. Water security and sustainable development. Insights Reg. Dev. 1(4), 301–317 (2019).

Flores-Anderson, A. I. et al. Evaluating SAR radiometric terrain correction products: Analysis-ready data for users. Remote Sens. 15(21), 5110 (2023).

Vrînceanu, C. A., Grebby, S., & Marsh, S. (2023). The performance of speckle filters on Copernicus Sentinel-1 SAR images containing natural oil slicks. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology, 56(3), qjegh2022–046.

Markert, K. N. et al. Comparing Sentinel-1 surface water mapping algorithms and radiometric terrain correction processing in Southeast Asia utilizing Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 12(15), 2469 (2020).

Torres, R. et al. GMES Sentinel-1 mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 120, 9–24 (2012).

Sen, P. K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 63(324), 1379–1389 (1968).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13(9), 4349–4383 (2021).

Vorosmarty, C. J., Green, P., Salisbury, J. & Lammers, R. B. Global water resources: Vulnerability from climate change and population growth. Science 289(5477), 284–288 (2000).

Allen, M., Dube, O. P., Solecki, W., Aragón-Durand, F., Cramer, W., Humphreys, S., & Kainuma, M. (2018). Special report: Global warming of 1.5 °C. In Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 677.

Benzougagh, B., Al-Quraishi, A. M. F., Kader, S., Mimich, K., Bammou, Y., Sadkaoui, D., ... & Hakkou, M. (2024). Impact of Green Generation, Green Morocco, and Climate Change Programs on Water Resources in Morocco.

El Mekki, A. A., & Ghanmat, E. (2015). The challenges of sustainable agricultural development in southern and eastern Mediterranean countries: The case of Morocco. In Sustainable Agricultural Development (pp. 65–82). Springer.

Kmoch, L., Bou-Lahriss, A. & Plieninger, T. Drought threatens agroforestry landscapes and dryland livelihoods in a North African hotspot of environmental change. Landsc. Urban Plan. 245, 105022 (2024).

Benjaafar, H., Berrichi, A., El Jai, F., & Arabi, M. (2024). Green Morocco Plan and Moroccan legislation for the socioeconomic and sustainable development of agricultural cooperatives: Challenges and prospects. In E3S Web of Conferences, 527, 03003. EDP Sciences.

Amachraa, A. (2023). Navigating Morocco’s Agricultural Policy: Unraveling the Nexus of Water, Food Security, and Trade Tensions in Global Value Chains.

Teweldebrihan, M. D. & Dinka, M. O. Sustainable Water Management Practices in Agriculture: The Case of East Africa. In Encyclopedia 5(1), 7 (2025).

Moumane, A., Al Karkouri, J., & Mouhcine, B. (2025). Detailed JavaScript API for Google Earth Engine to Enhance Monitoring of Surface Water Dynamics in the Drought-Affected Mediterranean Region. In Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques in Hydrology (pp. 105–132). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-9651-3.ch004

Karmaoui, A. et al. Thirty years of change in the land use and land cover of the Ziz Oases (Pre-Sahara of Morocco) combining remote sensing, GIS, and field observations. Land 12(12), 2127. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122127 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.M.B., Z.S and Y.O. performed the data analysis and wrote the main manuscript text, with W.M.B. also developing the computation code. A.C. and Z.S. supervised the work. S.G., M.P. and G.O. contributed to the analysis, discussion, and manuscript review. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baba, W.M., Chehbouni, A., Ouassanouan, Y. et al. Monitoring water crisis from space across a Mediterranean region. Sci Rep 15, 23262 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06240-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06240-1