Abstract

The Three-River Headwater (TRH) region, located in the hinterland of the Tibetan Plateau (TP), has experienced significant wetting since the early 2000s. However, the potential contribution of external forcings to the growing frequency of extreme precipitation events in this area has been rarely examined. Here, we conduct an analysis on the change in daily maximum precipitation (Rx1day) in the TRH region, with a focus on the anomalous event in 2023, and an investigation into the influence of external forcings on the occurrence probability of the Rx1day events. The results indicate that extreme precipitation has increased in the TRH region, particularly after the early 2000s, with a record anomalous Rx1day event in 2023. Further analysis suggests that anthropogenic forcings may have reduced the probability of Rx1day events in general, though greenhouse gases have increased atmospheric water vapor, offsetting the effect of anthropogenic aerosols. And aerosol forcing inhibits Rx1day events mainly through dynamic processes. However, the occurrence probability of a 2023-like anomalous Rx1day event may have been primarily related to anthropogenic factors, with greenhouse gases playing a key role by enhancing atmospheric moisture. This study emphasizes the crucial role of anthropogenic forcings in precipitation extreme in the TRH region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Catastrophic events caused by extreme weather and climate account for more than 70% of natural disasters in China, significantly higher than the global average, causing a serious burden on the economy, sustainable development and people’s lives1. Thus, there is a growing demand for government policymakers and the public to understand the causes of extreme events2.

Mounting evidence presents a significant precipitation increase over the north Tibetan Plateau (TP) since the late 1990s3,4,5. Although this increase is mainly dominated by more light-to-moderate precipitation6,7, an upward trend in heavy precipitation days is observed in Northeastern TP and Western Tibet7. Due to diverse climate regimes and complex topography, precipitation patterns in the TP exhibits significant spatial variability and a less confident temporal tendency3. Located in the hinterland of the TP, the Three-River Headwater (TRH) region is highly sensitive to climate change and variability. Strenuous efforts have been devoted to revealing the decadal variability of precipitation in the TRH region8,9,10,11, particularly, the pronounced dry-to-wet shift of summer precipitation since the 2000s12,13,14,15. In addition, the precipitation extreme change accounts for a substantial portion of the increased summer precipitation in the TRH region12,16.

As natural forcings and internal climate variability alone cannot fully explain the observed changes in climate extremes, the contribution of anthropogenic external forcings has gained more attention. Specifically, detection and attribution of the mean and extreme climate change have been adopted to explain the extent to which human activity affects climate change. These studies can be categorized into two areas: the attribution of long-term change and that of single extreme events17.

Given the urgent need to understand the causes behind the increasing number of high-impact extreme weather and climate events, considerable studies have focused on the attribution of single events. It has been emphasized that human-induced climate change has a detectable impact on extreme events analyzed18, including the record global heat events of 2016, as well as recent abnormal heat waves and intense precipitation in eastern China19,20,21,22. For instance, anthropogenic forcing has been estimated to reduce the probability of a 28-day maximum precipitation event during the extended Meiyu season over the Yangtze River in 2020 by 46% (22–62%). Specifically, greenhouse gas forcing is found to be offset by the strong suppression of anthropogenic aerosol forcing23. Notably, event attribution studies aim to explain the effect of external forcing on the probability of an event of similar intensity, or the intensity of an event with similar probability, rather than determining whether the event is caused by external forcings24,25.

Previous studies have provided valuable insights into the mechanisms driving extreme precipitation variations12,26,27. In this study, we analyze the long-term change in daily maximum precipitation (Rx1day) events in the TRH region and its anomalous nature in 2023, investigating the influence of external forcings on the occurrence probability of these events. Exploring the impact of various external forcings on precipitation in the TRH region, not only enhances understanding of events with important impacts on energy, water cycles and regional ecosystems, but also provides valuable references for formulating policies to adapt to extreme climate change by updating infrastructure design and minimizing socio-economic risks caused by extreme precipitation.

Data and methods

Data

The study area focuses on the TRH region (32°22′36″–36°47′53″ N, 89°50′57″–99°14′57″ E)28, located in the central and eastern part of the TP. The boundary of the TP adopted in this study follows the 2021 dataset developed by Zhang et al.29 which was derived from a comprehensive analysis of ASTER GDEM, Google Earth remote-sensing imagery, and other geospatial data. The study area is located in its central-eastern sector and is characterized by an average altitude exceeding 4000 m (Fig. 1). The boundaries of the study area refer to Wei28. The station observational daily precipitation data are from the “Daily Dataset of Basic Meteorological Elements from National Surface Weather Stations in China (V3.0)” and the reanalysis daily gridded precipitation dataset for the Chinese mainland (CHM_PRE)30. The reanalysis daily precipitation used is sourced from the ERA5_Land reanalysis dataset27,28. ERA5_Land data covers the period from 1961 to 2023 with a spatial resolution of 0.1°, while CHM_PRE data spans 1961 to 2022 with a 0.5° resolution. The CHM_PRE dataset is derived from daily precipitation data collected from 2,839 observational stations across China since 1961, undergoes strict quality control. It is noted to have effectively captured the spatial variability of precipitation and demonstrated strong consistency with widely used datasets, such as CGDPA, CN05.1 and CMA V2.0.

(a) Map of China with a rectangular frame indicating the geographical location of the TRH region, (b) Enlarged map of the TRH region, showing the divisions and boundaries of the Yangtze River Source, Yellow River Source, and Lancang River basins. The illustration was created using Python, and the boundary data of the TRH Region were obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/home.

Model simulations are obtained from the Detection and Attribution Model Intercomparison Project (DAMIP) within the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). Four simulation experiments are used: the historical experiment (ALL), the historical experiment driven by changes in natural only (NAT), the historical experiment driven by changes in well-mixed greenhouse gas only (GHG), and the historical experiment driven by changes in anthropogenic aerosol emissions only (AA). Since the historical simulation experiment ends in 2014, projections under the SSP1-2.6 Scenario are applied to extend the simulation to 2020, ensuring consistency in the time frame across ALL forcings and each single-forcing. Due to data limitations, the lack of NAT forcing for Max Planck Institute Earth System Model 1.2 Low Resolution (MPI-ESM1-2-LR) and single-forcing for Community Earth System Model Version 2 (CESM2) is only available to 2015, resulting in eight model simulations being ultimately included in the study (Table 1). Additionally, models such as Australian Community Climate and Earth-System Simulator-Climate Model version 2 (ACCESS-CM2), Canadian Earth System Model version 5 (CanESM5), Flexible Global Ocean–Atmosphere–Land System Model, Grid-point version 3 (FGOALS-g3), and Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model version 2.0 (MRI-ESM2-0) are considered as optimal for simulating precipitation in the TP31,32.

Statistical methods

The impact of anthropogenic forcing (ANT) is examined by comparing ALL and NAT simulations, and the impact of GHG (AA) forcing is examined by comparing the differences between ALL and AA (GHG) simulations23. Two hypotheses need to be emphasized (illustrated by the example of estimating GHG forcing): the difference between ALL and AA forcing is dominated by GHG and NAT forcings, while other external forcings, such as ozone and land-use, play a lesser role; NAT forcing has little effect on the probability of extreme precipitation on several decadal scales23. In this study, the RX1day anomaly percentage and its change under GHG forcing are statistically stronger than under NAT forcing, indicating that extreme precipitation shows no significant long-term trend in response to natural forcing alone.

The reanalysis data and model simulations are bilinearly interpolated onto a 0.5° longitude-latitude grid before calculating the precipitation extreme indices. Three indices are employed, representing the annual maxima of daily and consecutive 3-, 5-day precipitation accumulations (RxNday, where N = 1, 3 and 5). Regional indices are derived by averaging all gridded precipitation extreme indices. Furthermore, the extreme precipitation indices calculated are then converted to the percentage anomalies with respect to the 1961–1990 climatological mean for each index. Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) is used to fit the Probability Density Function (PDF) of precipitation extreme indices. The Kolmogorov-Smirnoff (K-S) test is used to evaluate the performance of the model-simulated precipitation variability.

The specific implementation procedures of the above methods are shown in detail in Fig. 2.

Evaluation of ERA5_Land and CMIP6 model simulation data in the TRH region

The CHM_PRE and station-based observational data are compared with ERA5_Land reanalysis data and model simulation data, respectively, to verify the reliability of the ERA5_Land dataset in the TRH region. Figure 3 illustrates the spatial distribution in the climatology of annual precipitation amounts in the TRH region based on eight climate models, multi-model mean, ERA5_Land data, CHM_PRE and observational data. A consistent gradient of decreasing precipitation from southeast to northwest is observed. However, models generally simulate a wetter climate than ERA5_Land, and both datasets indicate wetter conditions compared to observational data.

Regarding extreme events, there is better consistency in the climatology of Rx1day between ERA5_Land and observational data, although CHM_PRE and station-based data remain drier and wetter, respectively (Figs. 4, 5). The extreme anomalies of Rx1day in 2023 are consistent between different datasets, and the station-based observational data show that the Rx1day anomaly in 2023 reached 25.6%, surpassed only by the 2016 value of 27.6%, making it the second-highest recorded anomaly during the 1980–2023 period (Fig. 6). This finding is further corroborated by the ERA5_Land dataset results, which show a significant anomaly of 17.2% for the same year. Thereby, ERA5_Land reanalysis data, which extend to 2023, are utilized for subsequent analysis. On the other hand, the modeled Rx1day values are also found to be wetter compared to ERA5_Land and CHM_PRE. Better performance in simulating Rx1day appears in multi-model mean, albeit with a wet bias in climatology and its temporal changes (Figs. 4, 5, 8a). This performance advantage is further validated through quantitative evaluations, including normalized root mean square error, correlation coefficient and standard deviation ratio between the multi-model mean and ERA5_Land data (Fig. 7). Thus, the subsequent analysis associated with model simulation relies on the multi-model mean.

As for Fig. 3, but for Rx1day.

Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that the K-S significance test indicates a significant difference between model simulations and reanalysis data when fitted with a GEV distribution, while the multi-model mean reasonably simulates the PDF of Rx1day (Fig. 8b). And the effectiveness by using GEV performs better than applying other techniques (e.g., Gamma and logarithmic logic distributions).

Results

Temporal evolution of Rx1day and its anomalous in 2023 in the TRH region

A significant upward trend in the RxNday anomalies from 1980 to 2023 has been identified in the TRH region (p < 0.1) (Fig. 9). This increase becomes more pronounced as the duration of precipitation events (N value) grows, with the linear trend rising from 1.09%/decade for Rx1day to 1.74%/decade for Rx5day. Notably, the enhancement in precipitation extreme intensifies after the 2000s, while prior to this period, RxNday changes remained stable or declined.

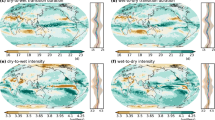

In 2023, the percentage of Rx1day anomaly reaches 17.2% in the TRH region, the highest recorded since 1980. Spatially, the Rx1day and Rx3day anomalies are predominantly positive across the TRH region when compared with the long-duration precipitation (Rx5day), particularly in the central portion (Fig. 10). This anomaly is closely linked to the significant positive precipitable water vapor anomaly (Fig. 11a). The highest Rx1day anomalies in 2023 occurred due to events on June 27th, August 3rd, 5th, 8th , 13th and 15th. These events are associated with abundant water vapor and strong convergence, as seen from the vertical integral of water vapor flux divergence pattern from 1000 to 300 hPa (Fig. 11b).

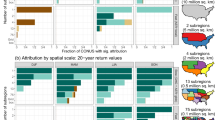

Impact of external forcings on the Rx1day events probability

To explore the response of the probability of occurrence of events to various external forcings, the PDF of Rx1day from model simulations under different experiments is compared (Fig. 12). ANT forcing is seen by the leftward shift in the PDF, by comparing the Rx1day under the ALL and NAT forcings. However, for the tail of the PDF, corresponding to the percentage of Rx1day anomalies up to 7.88% (purple dashed line), ANT forcing shifts the PDF rightward. It indicates that, in general, the occurrence probability of Rx1day events is inhibited by ANT forcing in the TRH region for the past several decades, while the probability of more anomalous Rx1day events is promoted by it, corresponding to the black dashed line in Fig. 12.

PDF of the percentage of Rx1day anomalies in the TRH region under different external forcings based on GEV fitting. Results from historical simulation experiments include: all historical forcings (blue), natural forcings only (red), anthropogenic aerosol forcings only (yellow), and greenhouse gas forcings only (green). The purple dashed line denotes the critical threshold of anthropogenic forcing impacts on the occurrence probability of extreme precipitation, while the black dashed line indicates the occurrence probability of extreme precipitation events analogous to those in 2023.

For instance, the 2023-like event, with a high outlier value of 17.2%, has an occurrence probability of 0% under NAT forcing but 0.00056% under ALL forcing. Thereby, ANT forcings substantially increase the likelihood of such extreme events. Among ANT forcings, GHG is estimated to play a crucial role in this change. When comparing ALL and AA simulations, the PDF under ALL forcing is shifted to the right, meaning that GHG forcing increases the probability of Rx1day events, including the anomalous 2023-like events, despite their low overall probability.

However, most Rx1day events exhibit anomalies of less than 7.8% in the TRH region, where ANT forcing generally suppresses their occurrence (Fig. 13c). Specifically, the net impact of ANT forcing results from the opposing effects of GHG and AA forcings: while GHG promotes Rx1day events, AA significantly inhibits them, except in the Yellow River source region (Fig. 13a, b).

GHG-induced warming leads to an increase atmospheric water vapor content, in line with the Clapeyron-Clausius equation. The increase of atmospheric water vapor content is conducive to the increase of heavy precipitation, as seen in the changes of climatology in precipitable water vapour and Rx1day (Figs. 13, 14a). On the other hand, AA forcing reduces precipitable water vapour through its cooling effect, thereby decreasing heavy precipitation through thermodynamic effects (Figs. 13, 14b). Nevertheless, the combined influence of GHG and AA forcings still results in an overall increase in precipitable water vapor, favoring the occurrence of Rx1day events (Fig. 14c). Thus, it reveals that, AA forcing plays a role more through dynamic effects in regulating atmospheric circulation changes and ultimately affect Rx1day events, given the fact that the thermodynamic effect of it is insufficient to fully explain the Rx1day change.

As for Fig. 13, but for the climatology of precipitable water vapour (units: %).

Discussion

Comparison with previous research

Previous studies on short-duration extreme precipitation events in China have emphasized the increasing influence of human activities (GHG forcing), particularly through the enhancement of atmospheric water vapor content due to warming19,21,22,33,34. Our research found that, in general, the occurrence probability of Rx1day event is inhibited by ANT forcing in the TRH region for the past several decades, with a greater cancellation between the effect of AA and GHG forcings. Nevertheless, GHG forcing increases the likelihood of more anomalous Rx1days, such as 2023-like event. These are more or less consistent with Wang et al.22, which concluded that the influence of human activities on extreme precipitation events has varied over time, and a stronger AA effect than GHG led to a net effect of ANT forcing to slightly reduce the probability of 1954-like event, though GHGs started to play a leading role in increasing heavy precipitation after the early twenty-first century.

Prolonged heavy precipitation events and mean precipitation, on the other hand, may have been largely influenced by AA forcing21,22,33,35. Several studies suggest that human activities have reduced the occurrence probability of the Meiyu events over mid-lower reaches of the Yangtze River basin, which is potentially linked to circulation changes driven by AA emissions23,36,37. It indicates that AA-induced regional negative temperature anomalies weaken the East Asian and South Asian summer monsoon circulation by weakening the sea-land thermal gradient, which is also not conducive to the occurrence of heavy precipitation events. In addition, the dynamic processes of aerosols also include ways to enhance atmospheric stability. And different aerosol types also have different effects on monsoon circulation and precipitation in different regions, including local and teleconnection effects of aerosols. On the contrary, recent research highlight that AA forcing dominates the increase in water vapor over the northern TP. The uneven anthropogenic aerosol distribution over the Eurasia weakens westerly winds by two ways: a teleconnection pathway across Eurasia triggered by European aerosol emissions38, and a decrease in the meridianal troposphere temperature gradient over the Eurasia caused by uneven AA forcing39. These dynamic processes reduce water vapor export from the eastern boundary of TP and increase net water vapor density, likely contributing to the increase in precipitation in the northern TP.

Uncertainties and future prospect

Several uncertainties remain in this study, primarily related to the event attribution methodology, which relies heavily on climate models. Climate models are difficult to simulate the multi-decadal climate variability, particularly using multi-model mean. Due to the spatial–temporal scale in the study, there is also the possibility that internal climate variability may play a role in the extreme precipitation change in the TRH region. It should be verified by using different attribution methods in further study, given that the internal climate variability of Rx1day is not considered here.

The applicability of reanalysis and climate system model data is also a key consideration in assessing precipitation changes over the TRH region, due to the lack of observational data. The ERA5_Land precipitation data tends to overestimate the inter-annual to decadal variability, and also the long-term trend, of precipitation in the TP region. This bias could lead to uncertainty in verifying model products and attributing the extreme precipitation change to different external forcings, in spite of the fact that the bias in presenting long-term trend is smaller than that in portraying precipitation variability. The improvement of the reanalysis data in the TP, and probably an adjustment of the reanalysis data referring to a more complete coverage of historical observational data, will be expected in the future. While ERA5_Land precipitation product tends to overestimate daily precipitation in the TRH region, it remains more suitable for daily-scale precipitation analysis in China and its subregions compared to other reanalysis datasets40. Its daily series is verified to have a higher correlation coefficient with ground observation data, making it more reliable for capturing the precipitation events. Moreover, ERA5_Land outperforms five satellite-based precipitation products in the TP region41. Its extended time coverage, including data up to 2023, further supports its use in this study.

Our validation revealed a “wet bias” in the model outputs, which does not affect the qualitative conclusions of this study-i.e., the occurrence probabilities of most Rx1day events are slightly suppressed by anthropogenic forcing, with GHG forcing and AA forcing exhibiting pronounced competing effects. However, this bias may influence quantitative assessments by modulating the occurrence probabilities of Rx1day under different forcings, even though such impacts are only observed under GHG and ALL forcing scenarios.

Precipitation in the TRH and its sub-source areas showed an enhancement in the mid-to-late 1990s, with a notable dry-to-wet shift occurring in the 2000s12,13,14,15. Our findings indicate that the extreme precipitation also increased following this transition, with a noticeable increase in the Rx5day change. This index, due to its longer duration in the TRH region, effectively reflects the impacts of substantial accumulated rainfall. However, this change requires further validation through more reliable observational data.

The performance of general circulation models in simulating precipitation in the TP region has been limited, due to various factors such as the scarcity of observational data and the low resolution of the models. The limitation has generally resulted in a “wet bias”, where model-simulated mean precipitation is overestimated42,43,44,45,46. However, the performance of the latest CMIP6 model has been improved, with multi-model ensembles reducing the overestimation of precipitation by 40 mm annually compared to CMIP542. In this study, we applied the ensemble average of the selected models to minimize bias and uncertainty, a method previously shown to improve precipitation simulation accuracy43. Additionally, Zhang31 evaluated the performance of 24 general circulation models from CMIP6 in the TP region, identifying optimal models for simulating various climate elements. Notably, four of the general circulation models used in this study are among those identified as optimal for simulating precipitation in the TP, which also strengthens the reliability of our findings.

Conclusions

This study makes an effort to examine the 1980–2023 change in maximum daily precipitation (Rx1day) events in the Three-River Headwater (TRH) region, with a particular focus on the anomalous 2023 Rx1day event and the possible influence of external forcings on its occurrence probability. The following conclusions can be drawn.

-

a.

Extreme precipitation has an upward trend in the TRH region, which has further intensified since the early 2000s; an abnormal Rx1day was observed in 2023, which might be related to the abundant atmospheric water vapor content.

-

b.

The occurrence probability of most Rx1day events is slightly inhibited by anthropogenic forcings, among which the GHG and AA forcings show a strong competitive effect; AA forcing may have significantly contributed to a reduction in the probability of Rx1day through a regulation of circulation change, since the increase in atmospheric precipitable water due to GHG may have outweighed the reduction caused by atmospheric aerosols.

-

c.

The occurrence probability of anomalous 2023-like Rx1day events is attributable to anthropogenic forcings. Specifically, GHG forcing may have made such events more possible by increasing atmospheric precipitable water, even if the occurrence probability is small.

Data availability

The ERA5 reanalysis datasets (including precipitation and other meteorological variables) are available through the Copernicus Climate Data Store at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets. The Chinese mainland gridded precipitation dataset (CHM_PRE) is accessible via https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21432123.v4. Observational precipitation data from Chinese surface weather stations can be found at http://data.cma.cn/. The DAMIP simulation experiments can be found at https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. The river basin divisions and boundary datasets for the TRH region are accessible via the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/home). The definition of the TP boundary can be accessed via the URL: https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/61701a2b-31e5-41bf-b0a3-607c2a9bd3b3. All figures were generated using Python (https://www.python.org).

References

Jiang, T., Wang, Y., Zhai, J. & Cao, L. Study on the risk of socio-economic impacts of extreme climate events: Theory, methodology and practice. Yuejiang Acad. J. 1, 90–105 (2018) (in Chinese).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R. & Zhou B. (eds.) Cambridge University Press, 2391. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896 (2021).

Liu, Y., Chen, H., Li, H., Zhang, G. & Wang, H. What induces the interdecadal shift of the dipole patterns of summer precipitation trends over the Tibetan Plateau?. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 5159–5177. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.7122 (2021).

Sun, J. et al. Why has the inner Tibetan Plateau become wetter since the mid-1990s?. J. Clim. 33, 8507–8522. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0471.1 (2020).

Zhao, D., Zhang, L. & Zhou, T. Detectable anthropogenic forcing on the long-term changes of summer precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 59, 1939–1952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-022-06189-1 (2022).

Lu, H.-L. et al. Temporal variability of precipitation over the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and its surrounding areas in the last 40 years. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 1912–1934. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.7953 (2023).

Zhou, S., Wang, C., Wu, P. & Wang, M. Spatial and temporal distribution of heavy precipitation days over the Tibetan Plateau. ARid Land Geogr. 35, 23–31 (2012) (in Chinese).

Yi, X., Li, G. & Yin, Y. Spatio-temporal variation of precipitation in the Three-River Headwater Region from 1961 to 2010. J. Geogr. Sci 23, 447–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-013-1021-y (2013).

Meng, X., Deng, M., Liu, Y., Li, Z. & Zhao, L. Remote sensing-detected changes in precipitation over the source region of Three Rivers in the recent two decades. Remote Sens. 14, 2216 (2022).

Sun, B. & Wang, H. Interannual variation of the spring and summer precipitation over the Three River source region in China and the Associated Regimes. J. Clim. 31, 7441–7457. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-17-0680.1 (2018).

Dong, Y. et al. Teleconnection patterns of precipitation in the Three-River Headwaters region. China. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104050. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba8c0 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Increased southerly and easterly water vapor transport contributed to the dry-to-wet transition of summer precipitation over the Three-River Headwaters in the Tibetan Plateau. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 14, 502–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2023.07.005 (2023).

Zhao, R., Chen, B., Zhang, W., Yang, S. & Xu, X. Moisture source anomalies connected to flood-drought changes over the three-rivers headwater region of Tibetan Plateau. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 5303–5316. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.8147 (2023).

Li, S., Yao, Z., Wang, R. & Liu, Z. Dryness/wetness pattern over the Three-River Headwater Region: Variation characteristic, causes, and drought risks. Int. J. Climatol. 40, 3550–3566. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.6413 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Spatial-temporal characteristics of precipitation from 1960 to 2015 in the Three Rivers’ Headstream Region, Qinghai, China. Acta Geophys. Sin. 74, 1803–1820 (2019) (in Chinese).

Zhao, R., Chen, B. & Xu, X. Intensified moisture sources of heavy precipitation events contributed to interannual trend in precipitation over the Three-Rivers-Headwater Region in China. Front. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.674037 (2021).

Balan Sarojini, B., Stott, P. A., Black, E. & Polson, D. Fingerprints of changes in annual and seasonal precipitation from CMIP5 models over land and ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL053373 (2012).

Herring, S. C. et al. Explaining extreme events of 2016 from a climate perspective. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, S1–S157. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-ExplainingExtremeEvents2016.1 (2018).

Burke, C., Stott, P., Ciavarella, A. & Sun, Y. Attribution of extreme rainfall in southeast China during may 2015. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, S92–S96. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-16-0144.1 (2016).

Sun, Q. & Miao, C. Extreme rainfall (R20mm, RX5day) in Yangtze-Huai, China, in June–July 2016: The role of ENSO and anthropogenic climate change. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, S102–S106. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0091.1 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Anthropogenic influence on 2018 summer persistent heavy rainfall in Central Western China. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, S65–S70. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-19-0147.1 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Human influence on historical heaviest precipitation events in the Yangtze River Valley. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 024044. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/acb563 (2023).

Zhou, T., Ren, L. & Zhang, W. Anthropogenic influence on extreme Meiyu rainfall in 2020 and its future risk. Sci. China Earth Sci. 64, 1633–1644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-020-9771-8 (2021).

Stott, P. A., Stone, D. A. & Allen, M. R. Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature 432, 610–614. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03089 (2004).

Hoerling, M. et al. Anatomy of an extreme event. J. Clim. 26, 2811–2832. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00270.1 (2013).

Du, J., Yu, X., Zhou, L., Li, X. & Ao, T. Less concentrated precipitation and more extreme events over the Three River Headwaters region of the Tibetan Plateau in a warming climate. Atmos. Res. 303, 107311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2024.107311 (2024).

Xi, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal changes in extreme temperature and precipitation events in the Three-Rivers Headwater Region, China. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 123, 5827–5844. https://doi.org/10.1029/2017JD028226 (2018).

Wei, Y. (ed Center National Tibetan Plateau Data) (National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, 2018).

Yili, Z. (ed Center National Tibetan Plateau Data) (National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, 2019).

Han, J., Gou, J. & Miao, C. (ed Center National Tibetan Plateau Data) (National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, 2023).

Zhang, J. et al. CMIP6 evaluation and projection of climate change in Tibetan Plateau (in Chinese). J. Beijing Normal Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 58, 77–89 (2022).

Li, B. & Hu, Q. Multi-scenario projection of future precipitation over the Qinghai-Xizang (Tibetan) Plateau based on CMIP6 model assessment results. Plateau Meteorol. 43, 59–72 (2024) (in Chinese).

Zhou, T. et al. Dynamic and thermal processes of anthropogenic aerosols causing precipitation reduction in global terrestrial monsoon regions. CIENCE CHINA Earth Sci. 50, 1122–1137 (2020) (in Chinese).

Li, H., Chen, H. & Wang, H. Effects of anthropogenic activity emerging as intensified extreme precipitation over China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 6899–6914. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD026251 (2017).

Song, F. & Zhou, T. The climatology and interannual variability of East Asian summer monsoon in CMIP5 coupled models: Does air–sea coupling improve the simulations?. J. Clim. 27, 8761–8777. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00396.1 (2014).

Tang, H. et al. Reduced probability of 2020 June–July persistent heavy Mei-yu rainfall event in the middle to lower reaches of the Yangtze River basin under anthropogenic forcing. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 103, S83–S89. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-21-0167.1 (2022).

Li, R. et al. Anthropogenic influences on heavy precipitation during the 2019 extremely wet rainy season in southern China. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 102, S103–S109. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-20-0135.1 (2021).

Wang, Z., Lei, Y., Che, H., Wu, B. & Zhang, X. Aerosol forcing regulating recent decadal change of summer water vapor budget over the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 15, 2233. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46635-8 (2024).

Jiang, J. et al. Precipitation regime changes in High Mountain Asia driven by cleaner air. Nature 623, 544–549. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06619-y (2023).

Zhou, Z., Chen, S., Li, Z. & Luo, Y. An evaluation of CRA40 and ERA5 precipitation products over China. Remote Sens. 15, 5300 (2023).

Jiang, Q. et al. Evaluation of the ERA5 reanalysis precipitation dataset over Chinese Mainland. J. Hydrol. 595, 125660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125660 (2021).

Lun, Y. et al. Assessment of GCMs simulation performance for precipitation and temperature from CMIP5 to CMIP6 over the Tibetan Plateau. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 3994–4018. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.7055 (2021).

Hu, Q., Jiang, D. & Fan, G. Evaluation of CMIP5 Models over the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 38, 924–938 (2014) (in Chinese).

Zhou, T. et al. The near-term,mid-term and long-term projections of temperature and precipitation changes over the Tibetan Plateau and the sources of uncertainties. J. Meteorol. Sci. 40, 697–710 (2020) (in Chinese).

Su, F., Duan, X., Chen, D., Hao, Z. & Cuo, L. Evaluation of the global climate models in the CMIP5 over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Clim. 26, 3187–3208. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00321.1 (2013).

Yang, T. et al. Multi-model ensemble projections in temperature and precipitation extremes of the Tibetan Plateau in the 21st century. Global Planet. Change 80–81, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2011.08.006 (2012).

Funding

This work is supported by Science and Technology Program of Qinghai Province (2025-ZJ-925). .

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: X. L., D. Z., G. R.; Methodology: X. L., D. Z., G. R.; Investigation: X. L., S. K. T.; Visualization: X. L., M. Z.; Supervision: S. K. T.; Writing-original draft: X. L., S. K. T.; Writing—review & editing: S. K. T., D. Z., G. R., H. L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, X., Zhong, D., Ren, G. et al. Possible influence of human activity on the daily maximum precipitation events over the Three-River Headwaters region of the Tibetan Plateau. Sci Rep 15, 23592 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06278-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06278-1