Abstract

We present a theoretical study of the low lying adiabatic relativistic electronic states of lanthanide monohydroxide (Ln-OH) molecules near their linear equilibrium geometries. In particular, we focus on heavy, magnetic DyOH and ErOH relevant to fundamental symmetry tests. We use a restricted-active-space self-consistent field method combined with spin-orbit coupling as well as a relativistic coupled-cluster method to determine ground and excited electronic states. In addition, electric and magnetic dipole moments are computed with the self-consistent field method. Analysis of the results from both methods shows that the dominant molecular configuration of the ground state is one where an electron from the partially filled and anisotropic 4f orbital of the lanthanide atom moves to the hydroxyl group, leaving the closed outer-most \(\hbox {6s}^2\) lone electron pair of the lanthanide atom intact in sharp contrast to the bonding in alkaline-earth monohydroxides and YbOH, where an electron from the outer-most s shell moves to the hydroxyl group. For linear molecules the projection of the total electron angular momentum on the symmetry axis is a conserved quantity with quantum number \(\Omega\) and we study the polynomial \(\Omega\) dependence of the energies of the ground states as well as their electric and magnetic moments. We find that for both molecules \(\Omega\) lies between \(-15/2\) and \(+15/2\), where the degenerate states with the lowest energy have \(|\Omega |=15/2\) and 1/2 for DyOH and ErOH, respectively. The zero field splittings among these \(\Omega\) states is approximately \(hc\times 1000\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), where h is the Planck constant and c is the speed of light in vacuum. We find that the permanent dipole moments for both triatomics are fairly small at 0.23 atomic units and are mostly independent of \(\Omega\). The magnetic moments are closely related to that of the corresponding atomic \(\hbox {Ln}^+\) ion in an excited electronic state. From the polynomial \(\Omega\) dependences, we also realize that the total electron angular momentum is to good approximation conserved and has a quantum number of 15/2 for both triatomic molecules. We describe how this observation can be used to construct effective Hamiltonians containing spin–spin operators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lanthanide atoms have a submerged open 4f electron-shell lying underneath a \(\hbox {6s}^2\)-closed shell. Experimental breakthroughs in the creation of ultracold quantum gases of these atoms with their large magnetic moments1,2,3,4 have opened a scientific playground in which to study quantum magnetism at the interface between condensed matter and atomic physics. In addition, these magnetic lanthanides have a large electronic orbital angular momentum leading to anisotropies, i.e. orientation dependencies, in their mutual interactions. Anisotropic interactions are crucial for using ultracold lanthanide atoms in spin-based quantum computing and simulations of orbitronics5,6.

The idea of integrating distinct physical components into a hybrid quantum system has also received significant attention. Hybrid approaches promise to take advantage of each components best properties, thereby realizing new tools for quantum information processing, condensed matter physics, and high-precision measurements. Our objective in this paper is to explore a novel class hybrid quantum system, hybrid magnetic lanthanide molecules, where lanthanide (Ln) atoms are brought and bound together with hydroxyl radical. These triatomic molecules are expected to possess features that are not present in lanthanide atoms.

Heavy atoms bound to hydroxyl or alcoxy groups stand out as candidates for precision measurements in search of physics beyond the standard model7,8,9,10,11. Among these systems are molecules containing heavy atoms with octupole deformed nuclei, such as isotopes of Fr and Ra, but also lanthanides and even actinides12. Octupole deformed nuclei have a Schiff moment and thus are sensitive probes of violations of the charge-parity (CP) symmetry13,14,15,16,17. In these molecules, the electronic structure can enhance the effect of the nuclear Schiff moment and lead to observable parity breaking terms in the ro-vibrational molecular Hamiltonian. These systems can also enhance the effects of a nuclear electric dipole moment17,18,19,20.

A second reason for our interest in DyOH and ErOH is that they might be amenable to laser cooling. Laser cooling of atoms is possible for atoms that contain a non-degenerate two level system, where the higher energy state predominantly decays back to the lower energy state by the emission of a “spontaneous” photon, typically in or around the optical frequency domain. Such closed systems naturally occur in alkali-metal and alkaline-earth atoms. On the other hand, Dy and Er have a complex level structure, often with metastable states, and successful cooling seems a challenging proposition. Nevertheless, Refs.3,21,22 showed that despite the possible optical leaks, the large electronic angular momenta of Er and Dy states make laser cooling feasible. Recently, laser cooling has also been reported for CaOH, SrOH, and YbOH8,23,24 even though molecules have even more ways to have optical leaks. For these three molecules cooling is possible due to the existence of so-called vertical transitions, where the lower- and higher-energy potential energy curves have very similar equilibrium geometries and harmonic spring constants or vibrational structure.

Previous studies of the electronic ground state of LnOH used density functional theory (DFT)25 and predicted that the equilibrium geometry of these molecules for all atoms in the lanthanide series is linear with the oxygen atom in the middle. Moreover, the lanthanide atom loses one electron from its 6s shell to OH, the bond between the lanthanide and the hydroxide is a covalent triple bond, and the partially filled 4f shell is only weakly involved in the bond.

We will describe calculations of the relativistic electronic eigenstates of DyOH and ErOH using restricted-active-space self-consistent-field calculations combined with computed spin-orbit matrix elements within the OpenMolcas package26 as well as using a relativistic coupled-cluster method within the CFOUR package27,28. Within the self-consistent-field method, we also compute electric and magnetic dipole moments. We obtain a different bonding model between the lanthanide atom and the hydroxyl group than that found within DFT. The molecules are still linear at their equilibrium geometries and the lanthanide atom still loses one electron to OH. We, however, find that the 4f shell participates significantly in the bonding. We show that the \(\hbox {4f}^n\) configuration of the lanthanide atom with \(n=10\) and 12 for Dy and Er, respectively, mixes with the \(\hbox {2p}^5\) configuration of the tightly-bound ground-state OH, leading to “spin-orbit” states of the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) configuration as the ground and lowest-energy eigenstates. The spin-orbit components of the \(4\text{f}^{n}6\text{s}+2\text{p}^6\) configuration, where the 6s lanthanide orbital has lost an electron, have significantly higher energies. The authors of Ref.29 found a similar behavior in the isoelectronic DyF using a four-component relativistic configuration-interaction approach. Recently, Ref.12 confirmed this bond for DyF.

Results

The DyOH and ErOH bond and zero field splittings

We begin by making some general observations about our triatomic systems. Heavy-element-containing molecular systems are difficult to model as relativistic electronic-structure methods are required. Further complicating the calculations for triatomic molecules is that the (relativistic) Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation can more easily break down than in diatomic molecules. Hence, a large number of adiabatic potential energy surfaces and electronic states are involved in the atomic motion. A theoretical analysis of the large number of electronic states in terms of spherical spin tensor operators, describing the coupling of the spins and angular momenta in the system, is convenient in order to account for non-adiabatic coupling among the states. For our DyOH and ErOH systems with their odd number of electrons, the relevant states turn out to correspond to different orientations of the combined spins and orbital angular momenta of the electrons in the submerged 4f shell.

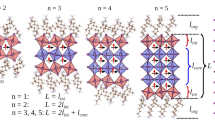

Potential energies of the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) and \(4\text{f}^{n}6\text{s}+2\text{p}^6\) electronic configurations of DyOH (panel (a)) and ErOH (panel (b)) near their equilibrium geometries as functions of the X-O separation with \(X=\text{Dy}\) or Er for a linear geometry and at a fixed O-H separation of \(1.80a_0\). For each configuration the curves correspond to states with different \(\Omega\) (or more precisely \(|\Omega |\)). Curves with the same color have the same \(|\Omega |\). The zero of energy is at the equilibrium geometry of energetically lowest potential. The potentials have been obtained with self-consistent-field calculations using basis sets that do not include excitations into 6p and 5d molecular orbitals. Panel (c) shows the splittings among the \(\Omega\) states of the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) configuration (colored circles). The energies have been obtained with self-consistent-field calculations using basis sets that do include excitations into 6p and 5d molecular orbitals. The dashed curves through the markers are fits to these data and are described in the text.

The DyOH and ErOH triatomics at their equilibrium geometries are linear molecules, where the lanthanide atom is bound to the O-side of the OH radical, as confirmed by both OpenMolcas and CFOUR package simulations. Consequently, the natural body-fixed Cartesian coordinate system is one where the positive z axis points from the lanthanide to the oxygen atom and the x and y axes form a plane perpendicular to this symmetry axis. For a non-relativistic description of linear molecules, electronic eigenstates are labeled by the spin multiplicity of the total electronic spin \(\textbf{S}\) and projection quantum number \(\Lambda\) of the total electronic orbital angular momentum \(\textbf{L}\) along our body-fixed z axis. In a relativistic description of the electrons, molecular electronic levels only conserve \(\Omega =\Lambda +\Sigma\), where \(\Sigma\) is the projection quantum number of \(\textbf{S}\) along the z axis.

For linear geometries, potentials \(V_{c\Omega }\) and kets \(|c,\Omega \rangle\) will denote electronic eigenenergies and eigenstates, respectively. Here, c labels the dominant molecular configuration of an eigenstate. For example, \(c=4\text{f}^{10}6\text{s}+2\text{p}^6\), \(4\text{f}^96\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\), or \(4\text{f}^96\text{s}6\text{p}+2\text{p}^6\) for DyOH. Finally, electronic eigenstates with quantum numbers \(-\Omega\) and \(+\Omega\) for \(\Omega >0\) are degenerate. For half-integer \(\Omega\), these degenerate pairs are Kramers’ doublets30.

After these preliminaries, we are ready to describe our results. Figure 1a,b show one-dimensional slices through the three-dimensional relativistic potentials \(V_{c\Omega }\) obtained with non-relativistic restricted-active-space self-consistent-field (RAS-SCF) calculations that do not include excitations to the 6p and 5d molecular orbitals at each molecular geometry, followed by the evaluation of spin-orbit matrix elements among a limited number of non-relativistic eigenstates and diagonalization of the electronic Hamiltonian within this subset of states. In the absence of the 6p and 5d orbitals, the SCF simulations correspond to complete-active-space SCF calculations (CAS-SCF) with 4f and 6s orbitals. The active space has zero orbitals, 8 orbitals, and zero orbitals in space RAS1, RAS2, and RAS3, respectively, with 11 electrons active in DyOH and 13 in ErOH.

In Fig. 1a,b, we draw the potentials for linear molecules as functions of the Ln-O separation near the equilibrium geometry of DyOH and ErOH with the O-H separation fixed at its equilibrium separation of \(1.80a_0\) for both triatomics. The RAS-SCF simulations show that the ground-state geometry corresponds to a linear molecule for both DyOH and ErOH. All separations are in units of the Bohr radius \(a_0\) and energies in units of \(hc\times\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), where h is the Planck constant and c is the speed of light in vacuum. Values for these constants in SI units as well as that for the elementary charge e and the Bohr magneton \(\mu _\text{B}\), both used later on, are taken from Ref.31. We provide more details about the electronic structure calculations in Methods.

First we note that the relativistic potentials in Fig. 1a,b are assigned to the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) or \(4\text{f}^{n}6\text{s}+2\text{p}^6\) configurations. In fact, several “bundles” of levels, well separated in energy, are assigned with these two configurations. Crucially, we predict that many states assigned to the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) configuration that have a lower energy than those of the \(4\text{f}^{n}6\text{s}+2\text{p}^6\) configuration. The largest energy difference is approximately \(hc\times 10,000\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\).

Second, we observe that for DyOH in Fig. 1a the absolute ground-state potential has quantum number \({|\Omega |=15/2}\) with a minimum energy when the Dy-O and O-H separations are \(3.76a_0\) and \(1.80a_0\), respectively. This compares well with our relativistic coupled-cluster calculations with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)) for this state. We find that the potential minimum occurs at a Dy-O separation of \(3.60a_0\), which is slightly shorter than that found with the SCF simulations due to a better inclusion of dynamic electronic correlation. The minimum energy of the potentials for states with \(|\Omega |<15/2\) of the lowest-energy DyOH “bundle” increases with decreasing \(|\Omega |\) corresponding to an inverted spin-orbit interaction. There are \(2\times 8=16\) levels in this grouping accounting for the twofold degeneracies. The second lowest “bundle” of states also assigned with the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) configuration has \(2\times 7=14\) states and contains pairs of levels for \(|\Omega |=13/2\) down to 1/2 in order of increasing energy. Finally, the bundles of potential energy curves assigned with the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) configuration are parallel within the accuracy of our simulations, i.e. have nearly the same equilibrium separation and force or spring constant (and thus harmonic frequency).

For ErOH in Fig. 1b the absolute ground state are the \({|\Omega |=1/2}\) leveld of the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) configuration. The corresponding potential has its minimum at Er-O and O-H separations of \(3.69a_0\) and \(1.80a_0\), respectively. The minimum energy of the potentials for states with \(|\Omega |>1/2\) of this lowest “bundle” increases with increasing \(|\Omega |\) up to \(|\Omega |=15/2\). The second lowest “bundle” has \(2\times 7=14\) states and contains pairs of levels for \(|\Omega |=1/2\) up to 13/2 in order of increasing energy. The potential energy curves assigned with the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) configuration are again parallel to good approximation.

For completeness, we note that from the SCF calculations, we find that the total electron spin of the non-relativistic DyOH and ErOH ground state are \(S=5/2\) and 3/2, respectively, corresponding to the spin-stretched state for both triatomics.

Figure 1c shows the DyOH and ErOH potential energies of the energetically lowest sixteen relativistic eigenstates, i.e. the first bundle or group of levels, at their equilibrium geometry as functions of \(|\Omega |\). These potential energies are evaluated from RAS-SCF calculations that include excitations to the 6p and 5d molecular orbitals. As mentioned before, this group of levels still remains energetically well separated from other groups of levels. Clearly shown is the inverted spin-orbit splittings for DyOH and the “normal” one for ErOH. The zero of energies are chosen to be at the \(|\Omega |=15/2\) and 1/2 states for DyOH and ErOH, respectively.

Isosurfaces of electronic Kohn-Sham molecular orbitals (MOs) for DyOH (panels (a,b)) and ErOH (panels (c,d)) at their equilibrium, linear geometries. In all panels the small, nearly hidden cyan, red, and gray balls correspond to the locations of the lanthanide, oxygen, and hydrogen atom, respectively. Panels (a,c) show some of the MOs for the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) configuration where the 4f and 2p orbitals overlap. The chosen 4f orbitals for DyOH and ErOH resemble the \(\hbox {f}_{xyz}\) and \(\hbox {f}_{yz^2}\) cubic or tesseral harmonic, respectively, while the 2p orbital resembles the \(\hbox {p}_z\) cubic harmonic with the lobes aligned along the z or Ln-O axis. Similarly, panels (c,d) show some of the MOs for the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}6\text{p}+2\text{p}^6\) configuration, where now the largest feature corresponds to the 6p orbital resembling the \(\hbox {p}_x\) or \(p_y\) cubic harmonic.

The equilibrium potential energies or zero-field splittings (ZFSs) of the \(c=4\text{f}^96\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) ground-state configuration of DyOH in Fig. 1c and with our choice for the zero of energy are well described by polynomial

for \(|\Omega |=1/2,\ldots ,15/2\), which ensures that eigenstates with \(-\Omega\) and \(\Omega\) are degenerate. Similarly, for the \(c=4\text{f}^{11}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) ground-state configuration of ErOH, the zero-field splittings are well described by

As the potentials for linear DyOH and ErOH are nearly parallel with Ln-O separation, the coefficients of the terms proportional to \(\Omega ^{2n}\) with \(n>0\) weakly depend on this separation. In fact, most separation dependence is isolated in the coefficient of the \(\Omega ^0\) term. Moreover, we focus on linear geometries as we believe that the Ln-O stretch mode will be of the most interest. This mode has the lowest vibrational energy, is well decoupled from other (bending) modes, and will likely hold true for both ground and excited electronic states. In a future publication, we plan to discuss these issues.

The energies of the levels in Eqs. (1) and (2) can be equivalently described by a spherical tensor-operator expansion once we assume that the electronic wavefunction is also an eigenstate of the square of the total electronic angular momentum of the molecule, \(\textbf{j}^2\). Here, we use the observations that (I) the group of levels contain one state for each \(|\Omega |\) up to 15/2, (II) the \(2\text{p}^6\) configuration of the \(\hbox {OH}^{-}\) negative ion has a closed and thus spin-less electron shell with \(j_{\text{OH}^-}=0\), and (III) the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2\) configuration of the atomic \(\hbox {Dy}^+\) and \(\hbox {Er}^+\) ion has total atomic angular momentum \(j_\text{atom}=15/2\) solely due to the open 4f shell32. Hence, we are justified in assuming that the total molecular electron angular momentum \(\textbf{j}=\textbf{j}_\text{atom} + \textbf{j}_\text{OH}\) has quantum number \(j=15/2\).

In a laboratory-fixed coordinate system (X, Y, Z) we can then write effective Hermitian potential operator

with the connection \(|c,\Omega \rangle \rightarrow |j\Omega \rangle\), energy coefficients \(a_i\) and dot product \(R_k\cdot S_k=\sum _{q=-k}^k(-1)^q R_{kq}S_{k-q}\) for arbitrary spherical tensor operators \(R_{kq}\) and \(S_{kq}\) of rank k, a non-negative integer. Moreover, tensor operators \(T_{kq}(\cdot ,\cdot )\) of rank \(k=2,3,\ldots\) are constructed from rank-1 total electronic angular momentum operator \(\textbf{j}\) and, finally, \(C_{kq}(\hat{R})\) are spherical harmonic functions, where unit vector \(\hat{R}=(\theta ,\varphi )\) describes the orientation of the symmetry axis of the linear triatomic molecule in the laboratory-fixed coordinate system. We follow the definition and notation for constructing tensor operators of Ref.33, functions \(C_{kq}(\hat{R})\) satisfy \(C_{kq}(\hat{0})=\delta _{q0}\), and quantity j in tensor operators, such as \(T_2(j,j)\) and \(T_3(j,T_2(j,j))\), is an abbreviation for dimensionless operator \(\textbf{j}/\hbar\), where \(\hbar\) is the reduced Planck constant, the atomic unit of angular momentum.

For the relevant eigenstates \(|c\Omega \rangle\) and, more precisely, \(|j\Omega \rangle\) in the body-fixed coordinate system with the z axis along the symmetry axis of the linear triatomic molecule and thus \(\hat{R}=\hat{0}\), the operator \(\hat{V}\) in Eq. (3) leads to eigen energies

using the Wigner–Eckart theorem with Clebsch–Gordan coefficients \(\langle j_1 j_2 m_1 m_2| jm\rangle\) and reduced matrix elements \(\langle j || T_k(.,.)||j\rangle\)33. We have explicitly evaluated the matrix element for the operator multiplying \(a_2\). The reduced matrix elements multiplying \(a_4\) and \(a_6\) can be evaluated with repeated use of Eq. (5.5) of Ref.33. We also realize that the Clebsch-Gordan coefficients \(\langle j k \,\Omega 0| j\Omega \rangle\) with \(k=2,4,6,\ldots\) in Eq. (4) are polynomials in \(\Omega ^2\) with degree k/2. For example, \(\langle j 4 \,\Omega 0| j\Omega \rangle\) is proportional to \(35 \Omega ^4+5[5-6j(j+1)]\Omega ^2+3(j+2)(j+1)j(j-1)\). Values for \(a_{i}\) with even \(i=0,2,\ldots\) can be found from a comparison with Eqs. (1) or (2) and solving a linear system for an upper-triangular matrix. Finally, we note that operator \(\hat{V}\) makes it possible to construct a Hamiltonian for the rotation of the triatomic molecule near their equilibrium geometry.

We have found it instructive to study the bonds in DyOH and ErOH by visualizing unit-normalized Kohn-Sham molecular orbitals (MOs) from DFT calculations even though these DFT calculations predict linear molecules with the incorrect order of eigenstate energies. The spin-unrestricted B3PW91 functional has been used with an all-electron scalar-relativistic basis set optimized for the Douglass-Kroll Hamiltonian, namely SARC2-QZVP-DKH2 for lanthanide atoms and AUG-CC-PVQZ-DK for the remaining atoms.

Figure 2 shows isosurfaces of DyOH and ErOH molecular orbitals with an isovalue of \(-0.0025e\)Å-3/2 and \(+0.0025e\)Å-3/2 for the MOs mainly composed of the lanthanide 6s, 4f and 6p atomic orbitals. Here, length 1Å is 0.1 nm. The DFT calculations have been performed within the Gaussian-16 package34 and visualized with Gauss-View 635. The atoms in the molecules are at their equilibrium locations. One can immediately observe that the 6s and 6p MOs easily enclose the Ln, O, H nuclei and that the 4f orbital has a radius close to the Ln-O equilibrium separation. In fact, the root-mean-square radius of the \(\hbox {6s}^2\) molecular orbital is \(7a_0\) larger than the equilibrium separation between the lanthanide and hydrogen atom of approximately \(3.7 a_0+1.8a_0=5.5a_0\).

Electronic eigenenergies (colored circles) of DyOH at its equilibrium, linear geometry as a function of electron projection quantum number \(\Omega\). The zero of energy is set at that of the lowest eigenstate. The excitation energies have been obtained with self-consistent-field calculations using basis sets that do include excitations into 6p and 5d molecular orbitals. For the lowest energies, lines connecting the colored circles correspond to states of the same configuration. For the higher energies, the lines although sorted by energy, are only guides for the eye. The blue arrow highlights the transition from \(\Omega =15/2\) to \(\Omega '=17/2\) between the \(\mathrm 6s^2\) and \(\mathrm 6s6p\) states. It has an electric dipole moment of \(1.79 ea_0\).

The excited level structure of the DyOH and ErOH molecules obtained using electronic structure calculations with a limited set of basis functions has been shown in Fig. 1a,b. Figure 3 shows the electronic eigenenergies of DyOH at its equilibrium geometry up to \(hc\times 30\,000\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\) above its ground state as functions of \(\Omega\) when we do include the 5d and 6p molecular orbitals. With these additional orbitals the equilibrium geometry is again linear. Below \(hc\times 10\,000\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\), states can still be assigned as belonging to the \(4\text{f}^{9} 6s{^2}+2p^6\) configuration and, in fact, have the same state ordering as before. For larger excitation energies and especially for states with a small \(\Omega\) mixing among the 6s, 5d, and 6p lanthanide molecular orbitals is strong and state assignment was not possible. For large \(\Omega\) we can make assignments and, for example, the arrow in the figure indicates the \(\Omega =15/2\) to \(\Omega '=17/2\) transition between the ground \(\mathrm 4f^{9} 6s^2+2p^6\) and excited \(\mathrm 4f^{9} 6s6p(^1P)+2p^6\) configurations. It has a computed transition electric dipole moment of \(1.79 ea_0\). Of course, calculations including the 6p and 5d orbitals are more accurate and we estimate that the relative uncertainty of the transition energies shown in Figs. 1c and 3 is about 10%.

Permanent electric dipole moment

We have also calculated permanent electronic dipole moments \(\textbf{d}\) for the \(\Omega\) states of the energetically lowest bundle or group of levels of configuration \({c=4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6}\). Our polar molecules can be controlled with a static electric field \(\textbf{E}\) via the Hamiltonian \(-\textbf{d}\cdot \textbf{E}\). Figure 4 shows matrix elements \(\langle c,+\Omega | d_{z} | c,+\Omega \rangle =\langle c,-\Omega | d_{z} | c,-\Omega \rangle\) for \(\Omega >0\) for DyOH and ErOH along the body-fixed z axis directed from the lanthanide atom to the oxygen atom. These data have been determined for the equilibrium linear geometries and obtained with the RAS-SCF method using basis sets that include excitations to the 6p and 5d molecular orbitals.

The permanent dipole moments are approximately \(0.28ea_0\) and \(0.20ea_0\) for DyOH and ErOH, respectively, as shown in Fig. 4, which indicates that the bond between the lanthanide atom and hydroxyl is not fully ionic. With \(R_\mathrm{Ln\text {-}O}\approx 3.7a_0\) at the equilibrium geometry of the triatomic molecules, less than 0.1 of an electron charge has transferred to the hydroxyl. We believe that this observation does not contradict the finding in the previous section that ground-state electronic configuration is to good approximation an eigenstate of \(\textbf{j}^2\) as the closed \(6s^2\) molecular orbital envelops the whole molecule as seen in Fig. 2. For both triatomics, the absolute ground state has the largest permanent dipole moment, although the \(\Omega\) dependence of the dipole moment is weak changing by no more than 20% for DyOH and significantly less for ErOH. Finally, we realize that we can write

for DyOH and

for ErOH, where we have omitted the bra and ket notation in the matrix elements for clarity.

Similar to Eq. (3), we can analyze the \(\Omega\) dependence of the permanent electric dipole moment with spin-spin tensor operators assuming that the total electron angular momentum is conserved. That is,

with coefficients \(d_{k}\) and rank-1 spin-spin operators \(T_1(T_{k}(\cdot ,\cdot ),C_{k+1}(\hat{R}))\) with even \(k=2,4,\ldots\). In Eq. (7), the space- or laboratory-fixed electric field \(\textbf{E}=(E_X,E_Y,E_Z)\) is expressed in “spherical” form, that is \(E_{\pm 1}=\mp (E_X\pm iE_Y)/\sqrt{2}\) and \(E_0=E_Z\), where X, Y, and Z define the space-fixed coordinate axes as before.

The diagonal matrix elements of these spin-spin operators in the basis \(|c,j\Omega \rangle\) and \(\hat{R}=\hat{0}\) lead to polynomials in \(\Omega ^{2}\) of degree k/2. For example, for \(k=2\) we have

Permanent dipole moment in atomic units \(ea_0\) as function of projection quantum number \(\Omega\) of states of the \(4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6\) electronic ground-state configuration of DyOH (orange filled circles) and ErOH (grey filled circles) at their equilibrium linear geometry. Solid black curves are polynomial fits to the data as described in the text.

Magnetic moments and pseudospin Hamiltonians for the ground-state configuration

The states of the linear DyOH and ErOH molecules can also be controlled by an external magnetic field \(\textbf{B}\) through the Zeeman interaction \(-\varvec{\mu }\cdot \textbf{B}\), where vector operator \(\varvec{\mu }\) is the electronic magnetic moment. Within OpenMolcas, we have computed the diagonal and off-diagonal matrix elements of \(\mu _\alpha\) of the magnetic moment operator projected along the body-fixed Cartesian axes \(\alpha =x\), y, and z for the \(2\times 8=16\) levels of the lowest-energy bundle assigned with configuration \({c=4\text{f}^{n-1}6\text{s}^2+2\text{p}^6}\). That is, the levels whose energies are shown in Fig. 1c.

Molecular g factors, \(g_\text{mol}\) as defined in the text, (a) and transition magnetic moments (b) as functions of \(\Omega\) for DyOH (orange filled circles) and ErOH (grey filled circles) at their linear equilibrium geometries along the body-fixed Ln-O axis. G-factors of the pseudo-spin are defined in the text. The DyOH and ErOH molecules are in their \(\hbox {4f}^9\hbox {6s}^2\)+\(\hbox {2p}^6\) and \(\hbox {4f}^{11}\hbox {6s}^2\)+\(\hbox {2p}^6\) ground-state configuration, respectively. In panel (a) the dashed orange and grey lines are the experimental g factors of the \(j=15/2\) level of the \(\hbox {4f}^9\hbox {6s}^2\) and \(\hbox {4f}^{11}\hbox {6s}^2\) configurations of \(\hbox {Dy}^+\) and \(\hbox {Er}^+\), respectively. In panel (a) the solid black curve is a polynomial in \(\Omega ^2\) found from a fit to the data for DyOH, while the solid black curves in panel b) correspond to a fit to adjustable parameter \(g_1\) times matrix elements of the angular momentum raising operator \(j_{+1}/\hbar\).

Following Ref.36 and assuming that the total angular momentum \(\textbf{j}\) is a conserved operator with quantum number \(j=15/2\), it is reasonable to initially propose \(\varvec{\mu }= g_\text{mol} \mu _\text{B} \textbf{j}/\hbar\), where dimensionless \(g_\text{mol}\) is a molecular g factor. Then because the zero field splittings of the relevant electronic states with different \(|\Omega |\) are well separated, the diagonal magnetic-moment matrix elements along the body-fixed z axis, \(\langle c,\Omega | \mu _z | c,\Omega \rangle = g_\text{mol} \mu _\text{B} \Omega\) will describe the level shifts of the molecular state in a magnetic field absent the rotation of the molecules.

Figure 5a shows the computed \(g_\text{mol}\) as functions of our half-integer \(\Omega\) for the ground-state configuration of DyOH and ErOH. The g-factors \(g_\text{mol}\) for both molecules are indeed mostly independent of \(\Omega\) as expected and are even functions of \(\Omega\). The magnetic moment operator \(\mu _{z}\) is thus an odd function of \(\Omega\). In fact, for DyOH a linear-least-squares fit with the cubic polynomial in \(\Omega ^2\) to the data in Fig. 5a gives

while for ErOH \(g_\text{mol}\) is independent of \(\Omega\) for \(\Omega >3/2\) but has significant deviations from this behavior for smaller \(\Omega\) likely indicating mixing with excited electronic configurations. (Polynomial fits to \(g_\text{mol}\) for ErOH do not lead to satisfactory agreements).

Interestingly, as also shown in Fig. 5a the atomic g factors for the \(j=15/2\) level of the \(\hbox {4f}^9\hbox {6s}^2\) configuration of an electronically excited \(\hbox {Dy}^+\) ion and that of the \(\hbox {4f}^{11}\hbox {6s}^2\) configuration of an excited \(\hbox {Er}^+\) ion are 1.333 and 1.200, respectively32, are in agreement with the molecular g factors. The agreement justifies our Ansatz that the ground states of DyOH and ErOH have a total molecular electronic angular momentum that is close to \(j=15/2\).

As with the relativistic energies in Eq. (1), the \(\Omega\) dependences can be described in terms of effective spin-spin interactions. The simplest extension for the magnetic moment operator is the rank-1 or vector operator

with g factors \(g_1\) and \(g_3\) in analogy to Eq. (3). This extension leads to matrix elements for \(\mu _z\) that are odd polynomials in \(\Omega\). For example, the spin dependence of the second term on the right hand side of Eq. (10) equals \(\Omega \{ 3j(j+1)-1-5\Omega ^2\}\) times a function that solely depends on j. For DyOH, more complex rank-1 operators containing spherical harmonics \(C_{4q}(\hat{R})\) and \(C_{6q}(\hat{R})\) can be added to represent the \(\Omega ^5\) and \(\Omega ^7\) dependence of \(g_\text{mol}\Omega\), respectively.

Figure 5b shows the transition magnetic moments between states with projection quantum numbers \(\Omega\) and \(\Omega -1\) of the \(c=4\text{f}^9\hbox {6s}^2\)+\(\hbox {2p}^6\) configuration of DyOH and the \(\hbox {4f}^{11}\hbox {6s}^2\)+\(\hbox {2p}^6\) configuration of ErOH. That is, we show matrix elements

as function of \(\Omega \ge 1/2\). Assuming that the states have \({j=15/2}\) and \(\varvec{\mu }= g_1 \mu _\text{B} \textbf{j}/\hbar\), we fit these data to matrix elements of operator \(g_1\mu _\text{B} j_{+1}/\hbar\) with adjustable g factor \(g_1\) using that

With \(j=15/2\), the fits lead to \(g_1=1.32691\) and 1.19430 for DyOH and ErOH, respectively, close to the values for the g-factors of the isolated excited \(\hbox {Dy}^+\) and \(\hbox {Er}^+\) ions given in two paragraphs earlier. Small deviations from the \(\Omega\) dependence in Eq. (12) are due to more complex rank-1 tensors as in Eq. (10).

Conclusion

We have argued that promising applications for ultracold molecules include performing precision spectroscopy to test the Standard Model of particle physics, creating new types of sensors, advancing quantum information science, simulation of complex exotic materials as well as the promise of quantum control of chemical reactions as each molecule can be prepared in a unique rovibrational quantum state.

In this paper, we have taken the first steps in understanding the properties of two magnetic Lanthanide monohydroxide molecules, Dy-OH and Er-OH, in these contexts. We computed ground and excited relativistic electronic energy levels near their linear equilibrium geometry, assigned their dominant electronic configuration, and realized that for the ground state an electron from the open submerged 4f shell moves into the \(\hbox {2p}^5\) orbital of OH. In addition, we showed that the molecules are both polar and paramagnetic by computing electric and magnetic moments and thus can be simultaneously manipulated by electric and magnetic fields. Most importantly, we find that the energetically lowest 16 states form a spin \(j=15/2\) system with zero field splittings on the order of a \(hc\times 1\,000\) \(\hbox {cm}^{-1}\). In fact, this spin system can be understood as being due to the \(j=15/2\) level of the \(\mathrm 4f^9 6s^2\) and \(\mathrm 4f^{11} 6s^2\) configurations of the isolated \(\hbox {Dy}^+\) and \(\hbox {Er}^+\) ions, respectively. The understanding on these magnetic molecules gained in this paper will enable us to start to study rotational and vibrational levels of the molecules as well as make suggestions for cooling the molecules with lasers and for studies of violations of the charge-parity (CP) symmetry.

Methods

We have performed multi-configuration restricted-active-space self-consistent field (RAS-SCF) electronic-structure calculations37 with spin-orbit coupling using state interaction (RAS-SI)38. In the state-interaction approach, spin-orbit matrix elements are based on the Douglas-Kroll Hamiltonian. The resulting low-dimensional \(D\times D\) Hamiltonian is diagonalized to obtain relativistic adiabatic potential energies and electronic wavefunctions. We use the implementation of the RAS-SCF and RAS-SI methods in OpenMolcas26 and rely on the built-in ANO-RCC-VQZP electronic basis39. For both DyOH and ErOH, we perform separate non-relativistic RAS-SCF calculations for total electron spin \(S=1/2\) (doublets), 3/2 (quartets), and 5/2 (sextets). For total electron spin S, we determine the energetically lowest \(D=80\) roots or eigenstates to ensure convergence with respect to couplings due to the spin-orbit interaction. We also use OpenMolcas to determine one-electron properties such as angular-momentum and permanent and transition electric and magnetic dipole moments between relativistic electronic states.

We verify the RAS-SCF and RAS-SI results with relativistic coupled-cluster calculations for the electronic ground state and equation-of-motion coupled-cluster calculations for some of the excited states using the CFOUR package equipped with additional modules27,40. That is, we use relativistic coupled-cluster calculations with single and double excitations (CCSD)41 augmented with non-iterative triples [CCSD(T)]42 and equation of motion CCSD43 calculations using the exact-two-component (X2C) Hamiltonian with atomic mean-field integrals (the so-called X2CAMF scheme)44,45. In the calculations, we use the all-electron uncontracted ANO-RCC-VTZP basis sets for the lanthanide atoms and the cc-PVTZ-X2C and cc-PVTZ-DK basis sets for the O and H atoms, respectively. The basis set for O is a “recontracted” basis for use in the X2CAMF scheme46.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lu, M., Burdick, N. Q., Youn, S. H. & Lev, B. L. Strongly dipolar Bose–Einstein condensate of Dysprosium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 190401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.190401 (2011).

Lu, M., Burdick, N. Q. & Lev, B. L. Quantum degenerate dipolar Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 215301. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.215301 (2012).

Frisch, A. et al. Narrow-line magneto-optical trap for erbium. Phys. Rev. A 85, 051401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.85.051401 (2012).

Aikawa, K. et al. Bose–Einstein condensation of erbium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 210401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.210401 (2012).

Go, D. et al. Toward surface orbitronics: Giant orbital magnetism from the orbital Rashba effect at the surface of sp-metals. Sci. Rep. 7, 46742. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46742 (2017).

Bernevig, B. A., Hughes, T. L. & Zhang, S.-C. Orbitronics: The intrinsic orbital current in \(p\)-doped silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 066601. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.066601 (2005).

Isaev, T. A., Zaitsevskii, A. V. & Eliav, E. Laser-coolable polyatomic molecules with heavy nuclei. J. Phys. B 50, 225101. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6455/aa8f34 (2017).

Kozyryev, I. et al. Sisyphus laser cooling of a polyatomic molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 173201. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.173201 (2017).

O’Rourke, M. J. & Hutzler, N. R. Hypermetallic polar molecules for precision measurements. Phys. Rev. A 100, 022502. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.100.022502 (2019).

Hutzler, N. R. Polyatomic molecules as quantum sensors for fundamental physics. Quantum Sci. Technol. 5, 044011. https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-9565/abb9c5 (2020).

Augenbraun, B. L., Doyle, J. M., Zelevinsky, T. & Kozyryev, I. Molecular asymmetry and optical cycling: Laser cooling asymmetric top molecules. Phys. Rev. X 10, 031022. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.10.031022 (2020).

Chen, T. et al. Relativistic exact two-component coupled-cluster study of molecular sensitivity factors for nuclear Schiff moments. J. Phys. Chem. A 128, 640. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.4c02640 (2024).

Auerbach, N., Flambaum, V. V. & Spevak, V. Collective T- and P-odd electromagnetic moments in nuclei with octupole deformations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 4316–4319. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.4316 (1996).

Dobaczewski, J. & Engel, J. Nuclear time-reversal violation and the Schiff moment of \(^{225}\rm Ra\). Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 232502. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.232502 (2005).

Skripnikov, L. V., Mosyagin, N. S., Titov, A. V. & Flambaum, V. V. Actinide and lanthanide molecules to search for strong CP-violation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 18374–18380. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0CP01989E (2020).

Yu, P. & Hutzler, N. R. Probing fundamental symmetries of deformed nuclei in symmetric top molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 023003. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.023003 (2021).

Flambaum, V. V. & Mansour, A. J. Enhanced magnetic quadrupole moments in nuclei with octupole deformation and their CP-violating effects in molecules. Phys. Rev. C 105, 065503. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.105.065503 (2022).

Sishkov, O. P., Flambaum, V. V. & Khriplovich, I. B. Possibility of investigation P- and T-odd nuclear forces in atomic and molecular experiments. Sov. Phys. JETP 60, 873–883 (1984).

Flambaum, V. V. Spin hedgehog and collective magnetic quadrupole moments induced by parity and time invariance violating interaction. Phys. Lett. B 320, 211–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(94)90646-7 (1994).

Flambaum, V. V., DeMille, D. & Kozlov, M. G. Time-reversal symmetry violation in molecules induced by nuclear magnetic quadrupole moments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 103003. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.103003 (2014).

McClelland, J. J. & Hanssen, J. L. Laser cooling without repumping: A magneto-optical trap for erbium atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 143005. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.143005 (2006).

Lu, M., Youn, S. H. & Lev, B. L. Trapping ultracold dysprosium: A highly magnetic gas for dipolar physics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 063001. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.063001 (2010).

Vilas, N. B. et al. An optical tweezer array of ultracold polyatomic molecules. Nature 628, 282–286. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07199-1 (2024).

Augenbraun, B. L. et al. Laser-cooled polyatomic molecules for improved electron electric dipole moment searches. New J. Phys. 22, 022003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/ab687b (2020).

Harb, H., Thompson, L. M. & Hratchian, H. P. On the linear geometry of lanthanide hydroxide (Ln-OH, Ln = La-Lu). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 21890–21897. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9CP01560D (2019).

Aquilante, F. et al. Modern quantum chemistry with Molcas. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 214117–214125. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0004835 (2020).

Stanton, J. F. et al. For the current version, see http://www.de, CFOUR, Coupled-Cluster techniques for Computational Chemistry, a quantum-chemical program package.

Liu, J. & Cheng, L. Relativistic coupled-cluster and equation-of-motion coupled-cluster methods. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 11, e1536. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1536 (2021).

Yamamoto, S. & Tatewaki, H. Electronic spectra of DyF studied by four-component relativistic configuration interaction methods. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 094312. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4913631 (2015).

Kramers, H. A. Théorie générale de la rotation paramagnétique dans les cristaux. Proc. Amst. Acad. 33, 959–972 (1930).

Tiesinga, E., Mohr, P. J., Newell, D. B. & Taylor, B. N. CODATA recommended values of the fundamental physical constants: 2018. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025010 (2021).

Kramida, A. et al. NIST Atomic Spectra Database (version 5.11). https://physics.nist.gov/asd; https://doi.org/10.18434/T4W30F (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023).

Brink, D. M. & Satchler, G. R. Angular Momentum (Oxford University Press, 1993).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16 Revision B.01 (Gaussian Inc., 2016).

Shao, Y. et al. Advances in molecular quantum chemistry contained in the Q-Chem 4 program package. Mol. Phys. 113, 184–215 (2015).

Chibotaru, L. F. & Ungur, L. Ab initio calculation of anisotropic magnetic properties of complexes. I. Unique definition of pseudospin Hamiltonians and their derivation. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 064112. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4739763 (2012).

Malmqvist, P.-A., Rendell, A. & Roos, B. O. The restricted active space self-consistent-field method, implemented with a split graph unitary group approach. J. Phys. Chem. 94, 5477–5482. https://doi.org/10.1021/j100377a011 (1990).

Malmqvist, P. A., Roos, B. O. & Schimmelpfennig, B. The restricted active space (RAS) state interaction approach with spin–orbit coupling. Chem. Phys. Lett. 357, 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2614(02)00498-0 (2002).

Roos, B. O. et al. New relativistic atomic natural orbital basis sets for lanthanide atoms with applications to the Ce diatom and \({{\rm LuF}}_3\). J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 11431–11435. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp803213j (2008).

Matthews, D. A. et al. Coupled-cluster techniques for computational chemistry: The CFOUR program package. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 214108. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0004837 (2020).

Purvis, G. D. III. & Bartlett, R. J. A full coupled-cluster singles and doubles model: The inclusion of disconnected triples. J. Chem. Phys. 76, 1910–1918. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.443164 (1982).

Raghavachari, K., Trucks, G. W., Pople, J. A. & Head-Gordon, M. A fifth-order perturbation comparison of electron correlation theories. Chem. Phys. Lett. 157, 479–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2614(89)87395-6 (1989).

Stanton, J. F. & Bartlett, R. J. The equation of motion coupled-cluster method. A systematic biorthogonal approach to molecular excitation energies, transition probabilities, and excited state properties. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 7029–7039. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.464746 (1993).

Liu, J. & Cheng, L. An atomic mean-field spin-orbit approach within exact two-component theory for a non-perturbative treatment of spin-orbit coupling. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 144108. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5023750 (2018).

Zhang, C. & Cheng, L. Atomic mean-field approach within exact two-component theory based on the Dirac-Coulomb–Breit hamiltonian. J. Phys. Chem. A 126, 4537–4553. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.2c02181 (2022).

Dunning, T. H. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. i. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 90, 1007–1023. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.456153 (1989).

Acknowledgements

The work at Temple University was funded by the AFOSR, Grant No. FA9550-21-1-0153, the National Science Foundation, Grant No. PHY-2409425, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Grant Id. GBMF12330. The work at Johns Hopkins University was supported by the National Science Foundation, Grant No. PHY-2309253.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Kotochigova performed electronic structure calculations and helped write the manuscript, E. Tiesinga participated in writing the manuscript, J. Klos performed the electronic structure and scattering calculations, L. Cheng performed electronic structure calculations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kłos, J., Tiesinga, E., Cheng, L. et al. Anisotropic chemical bonding of lanthanide-OH molecules. Sci Rep 15, 21480 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06281-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06281-6