Abstract

A perianal fistula is an abnormal tract connection between the anal canal and the surrounding skin of the perineum, with underdiagnosis in specific populations. The aim of this study was to diagnose and describe the intersphincteric perianal fistulas (number, site, number of internal and external openings, and length) using transcutaneous ultrasound (TCUS) imaging. This was a retrospective study included patients who underwent TCUS for clinically diagnosed of low-type intersphincteric perianal fistulas during April 2017–December 2022. A total of 581 perianal fistulas from 549 patients were included in this study. The mean age of the patients was 36.14 ± 13.37-year (range from 1 to 80 years). The majority were in the young adult age group, from 21 to 40 years (56.47%), 84% were male and 16% female. The patients predominantly had one fistula (94.35%) with one external opening (EO) (79.10%), and one internal opening (IO) (99.65%). The left quadrants (1–6 O’clock around the anus) were the most common sites of the EO (60.5%). The IO was 11–20 mm above the anal verge in 58.5% of fistulas and ≤ 10 mm in 27.4%. The length of the fistular tract was 21–30 mm in 30.1%, 11–20 mm in 27.4%, and 31–40 mm in 25.0%. The perianal fistulas in the left posterior quadrant had a significantly shorter fistular tract compared to those in the other three quadrants. There was no significant variation in the IO distance from anal verge between fistulas in the different anal quadrants. The solitary tract, IO and EO with the short length, and small distance of IO from the anal verge improve surgical outcomes and decrease complications and recurrence of the perianal fistulas. TCUS, when performed by an experienced operator, can be effectively utilized for the diagnosis and surgical planning of low-type perianal fistulas, with the offer of that it is a non-invasive, well-tolerated, and radiation-free imaging method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A perianal fistula is an abnormal tract connection between the anal canal and the surrounding skin of the perineum. It is hypothesized that it forms through an intersphincteric cryptoglandular infection leading to the formation of an abscess which can subsequently lead to the formation of a fistulous tract1. In European countries, the overall prevalence of a perianal fistula is 18.37 per 100,000 people2. Perianal fistulas exert a substantial negative impact on patients through a burden of symptoms including: Fistula-related pain, a significant source of impaired wellbeing, which often coincides with the initial diagnosis of the fistula; Fistula-related discharge; Fistula-related restricted mobility, and Fistula-related fatigue3. Although clinical examination can confirm diagnosis, fistulas may require medical imaging for the preoperative identification of the complex tract shape, number, internal orifices, and Park’s classification which plays a crucial role in effective management4.

According to the tract location relative to the internal and external anal sphincter, Park’s classification of the perianal fistula include: 1-Intersphincteric, which is confined to the intersphincteric plane, 2-Trans-sphinecteric, where the track passes radially through the external anal sphincter 3-Suprasphicteric, where the track passes upward within the intersphincteric plane over the puborectalis muscles and descends through the levator muscles and the ischiorectal fossa, and 4-Extrasphicteric, in which the course is completely outside the external anal sphincter5. Perianal fistula can be intersphincteric (simple fistula), transsphicteric, suprasphincteric (complex fistula), or extrasphincteric (horseshoe fistula)6. Diagnosis and classification of perianal fistulas mainly depend on medical imaging.

Imaging of the rectum and surrounding tissues is difficult and technically challenging, and conventional X-ray imaging and computed tomography (CT) barium studies offer limited information about the extension of the perianal fistulas7. Preoperative pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and endoanal ultrasonography (EAUS) are the first line imaging modalities for the evaluation of the perianal fistulas with better results and prognosis after surgery8. Conventional X-ray fistulography gradually lost its diagnostic value due to several of disadvantages including 1-the anorectal muscles cannot be imaged, 2- determination of the IO is often difficult, 3-it is an invasive technique with the risk of dissemination of sepsis, and 4-it can give a wrong impression of the presence of an extrasphincteric tract9. The inability of conventional X-ray and CT to show the fistula in relation to normal structures in a single image10, the CT radiation hazards11, the limited tolerance of the patient, and the operator and experience dependency of the EAUS12, the high cost of MRI13, in addition to the limited availability everywhere of MRI. All the above limitations create the need for an imaging modality that is effective, possible, and tolerable by the patient and a widely available imaging modality for the diagnosis of the perianal fistulas to plan for optimal management. The aim of this study was to describe the low-type intersphincteric perianal fistulas (number, site, number of EO, IO, and length of fistular track) using the TCUS. Characters of the intersphincteric perianal fistula including the length and distance of IO from the anal verge are critical points in surgical planning. The study was done in Hadramout region of Yemen which is a peripheral region in a developing country with a paucity of modern imaging methods to diagnose perianal fistulas such as endoanal ultrasound and MRI. The most available imaging method is TCUS which proved to be an effective diagnostic method for the common low-type perianal fistula.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

A retrospective study was conducted with the electronic records of patients clinically diagnosed with perianal fistulas and diagnosed between April 2017 and December 2022. The study was conducted at Alsafwa Consultative Medical Center (ACMC) in Almukalla city, Hadhramout, Republic of Yemen.

Study sample

The study involved 581 low-type intersphincteric perianal fistulas from the reports of 549 patients who underwent TCUS for clinically diagnosed perianal fistula.

Inclusion criteria

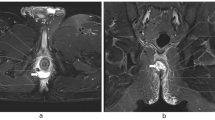

Any patient diagnosed with a low-type intersphincteric perianal fistula (Fig 1), regardless of their age, gender or the number of fistulas. Based on the location of the IO, perianal fistulas classified into low and high types. Low-type perianal fistulas are those with IO in lower regions of the external sphincteric muscle. High-type perianal fistulas are those with IO located near the deep part of the upper external sphincteric muscles5.

The diagram shows the anatomy of the anus (A), anal canal (from the skin to the dentate line (D), rectum (R), internal anal sphincter (IS), external anal sphincter (ES), and the different types of the perianal fistula including the inter-sphincteric fistula (1), trans-sphincteric fistula (2), supra-sphincteric fistula (3), and extra-sphincteric fistula (4).

Exclusion criteria

Patients with pilonidal sinus, perianal abscess, anal fissure, high-type perianal fistulas, and perianal fistula without an external opening were excluded from the study.

Ultrasound imaging procedure

All patients underwent perianal TCUS that were performed by a highly qualified radiologist with 12 years postdoctoral experience in general ultrasound imaging. A superficial linear transducer of 7.5 MHz, Mindray DC30 ultrasound machine was used to assess the perianal region in all the patients, and a deep curved probe of 3.5 MHz was used to follow the long tracts of some fistulas.

Scanning was performed in the knee-chest position or in left lateral decubitus position. The ultrasound probe was wrapped with a latex cover after applying a contact gel to its surface. TCUS scanning of the perianal region was performed in the sagittal, coronal, and axial planes. The probe was placed over the anal canal and the EO of the tract in all patients and ultrasound images was obtained in different planes as necessary. The distance of the IO of the fistula from the anal verge was described, the length of the tract was evaluated to the EO, and any ramifications in the tract was described14.

In the ultrasound images, the fistular tract appears as a tubular hypoechoic structure starting from the anal canal and extended to the perianal skin. A perianal abscess appears as a hypoechoic fluid-filled cavity in the perianal region15.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27 (IBM, Armonk, NY). I. Inferential statistics was used, categorial variables are presented as frequency and percentage, and the continuous variables as means ± standard deviation and median. The Shapiro-Wilk, and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests of normality revealed non-normality distribution of continuous categories length and distance of fistula (p < 0.001), for this reason the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess the differences of length in different age group and length and distance in the four perianal quadrants. Furthermore, for length of fistula as there was significant differences in different categories of perianal quadrants, the Dunn-Bonferroni-Tests was used to compare the group in pairs to assess which were significantly differs. Adjusted p-values ≤ 0.05 consider statistically significant for differences.

To generate Fig. 2, the Sketchbook (https://www.sketchbook.com/) was used. To enhance the resolution of our ultrasound images, the Snapedit.app (https://snapedit.app/ar/change-sky/upload) was used for Figures 3, 4, and 5.

An ultrasound image was taken by using a superficial linear probe (7.5 MHz) showing low type right sided perianal fistula, the right image shows the tract of the fistula (Thick white line), external opening (EO), Internal opening (IO), of the tract, around the anus (A), and anal canal (AC). Left image is the same clear image.

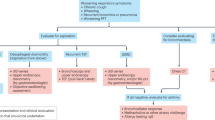

An ultrasound image was taken by using a superficial linear probe (7.5 MHz) showing the low type right sided branching perianal fistula, the right image shows the tract of the fistula (Thick white line), Internal opening (IO), first external opening (EO1), and second external opening (EO2) of the tract, around the anus (A), and anal canal (AC). The left image is the same clear image.

Results

A total of 581 intersphincteric perianal fistulas from 549 patients were included. Males represented the vast majority of the sample (83.97%), with 16.03% females. Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests of normality revealed non-normality distribution of patients ages (p < 0.001) with mean age was 36.14 ± 13.37 years (range from 1 to 80 years). Kruskal–Wallis test results showed significant difference in perianal fistula distribution in different age groups (p < 0.001) with the majority were in the young adult age group, aged 21 to 40 years (56.47%), followed by the group aged 41 to 60 years (31.88%). However, the test of homogeneity of variances (Levene statistics) showed normal distribution of perianal fistulas within age groups (p = 0.063). The patients predominantly had one fistula (n = 518, 94.35%), see Table 1.

The fistulas almost always had one IO (99.65%), and the majority had one EO (79.10%). The fistula EO was located mainly in the LAQ (31.5%), followed by the LPQ (29.1%). The most frequent sites of the EO around the anus were 6 o’clock (14.3%) and 1 o’clock (13.6%) (Fig. 2&3). The IO was often 11–20 mm above the anal verge (58.5%) or ≤ 10 mm (27.4%). The length of the tract of the fistula was 21–30 mm (30.1%), 11–20 mm (27.4%), and 31–40 mm (25.0%), see Table 2.

The Kruskal–Wallis test results indicated a significant variation in the length of the fistular tract between the different perianal quadrants (p < 0.001), see Table 3.

The Dunn-Bonferroni Post Hoc tests for comparisons of pairwise the length of the perianal fistular tract in the different perianal quadrants shows that the pairwise group comparisons of (LAQ)1–3—(LPQ)4–6, (LPQ) 4–6—(RPQ)7–9 and (LPQ) 4–6—(RAQ)10–12 demonstrated an adjusted p-value < 0.001), so these groups were significantly different in pairs, see Table 4.

Table 5 displays the mean distance of the fistular IO from the anal verge in the different perianal quadrants. The Kruskal–Wallis test shows no significant variation in the IO distance from the anal verge between the different perianal quadrants (p = 0.945).

From our work, we selected TCUS images for low-type intersphincteric perianal fistulas from different patients using a 7.5 MHz superficial linear probe (Figs. 3, 4), and an image of the perianal abscess using the same linear probe (Fig. 5).

Discussion

An optimal diagnosis and imaging of a perianal fistula is essential to plan the optimal management and achieve a satisfactory outcome of the surgery for the health and comfort of the patient. This article reports the age and gender distribution, the number, site, and length, of the common low-type of perianal fistulas using TCUS imaging easily available, and without any radiation hazards. We found that 69.26% of the patients were in the young adult (21–40 years) age group and the average age of the patients was 36.14 ± 13.37-years. This finding is compatible with a previous study which reported that most fistulas occur between 20 and 40 years of age with the average age of diagnosis 38 years16. In line with our results, the results of another study with 120 patients with a mean age of 39 years17.

Our results indicated that males are affected more than female (83.97% vs 16.03%). These results are compatible with the results in literature from 1969 to 1978, the mean incidence of perianal fistulas in the population of Helsinki was 12.3 and 5.6 per 100,000 for male and females, respectively18. Sanchez-Haro et al. reported that males were affected more frequently than females (70% vs 30%) among Spain inhabitants which was consistent with our results19. Our results are in line with a previous study in Saudi Arabia which reported an 80.1%:19.9% male: female rate, although it was high perianal fistulas20. Contradictory to our results, another study reported that the mean age of patients with perianal fistula was 44.3 ± 12.1 years old and the male-to-female ratio was 16:121. The predominant involvement of males, as explained by Shindhe et al., are repeated perianal infections, infection from a hair follicle, infected sweat or sebaceous gland, Crohn’s disease, etc.22.

The classification of perianal fistula as low or high is more practical than other classifications, with implications for the treatment. A low perianal fistula is defined as a fistula with a tract located in the lower third of the external anal sphincter, and a high perianal fistula as a fistula in which the tract runs through the upper two thirds of the external anal sphincter muscle. Low fistulas can be managed safely by fistulectomy23. In our study, 85.9% of the intersphincteric perianal fistulas were within 20mm, 10.8% were within 21-30mm, and 3.3% were within 31 to 50mm distance from the anal verge. This was explained by Amato et al. who reported that the source of most cases of perianal sepsis is a non-specific cryptoglandular infection starting in the intersphincteric space24. Fortunately, the gold standard surgical treatment for a low anal fistula fistulotomy with an 80–100% success rate, with the exception of up to 62% fecal incontinence rate25. The current study confirms that TCUS determination of the length, EO and IO of perianal fistula has a critical role in going to further investigation in high-type perianal fistulas, and surgical planning and improving surgical outcomes in low-type.

Our results showed that the most common site of the EO of the intersphincteric perianal fistula was at 6 o’clock. This result is compatible with a previous study who reported that the IO of the perianal fistulas mostly was at the middle posterior wall of the anal canal (6 o’clock)26. In line with our results, a study conducted by Chauhan et al. reported that 78% of the perianal fistulas were posterior27. A perianal fistula is considered high when its IO lies above the dentate line28. The anal verge and the dentate line are two reliable landmarks for distance measurements inside the rectum. The median distance from the anal verge to the dentate line is 20mm29. Our results showed that 85.9% of the perianal fistulas IOs were less than 20mm above the anal verge which is below the dentate line. Recently, proposed comprehensive novel template was suggested for optimal treatment planning using anal endosonography and MRI. The template includes the following: Fistula type according to Park’s classification; fistula clockwise position location according to the AC; fistula height; differentiation between simple and complex by the presence of secondary extensions in the later; location and patency of the IO; description of a residual abscess type and location according to the clockwise position; morphology of the anal sphincters; and schematic drawing of the anal canal30. In the current study, ANOVA test revealed significant variation in length of perianal fistulas which was 33.73 ± 14.48mm, 32.12 ± 12.46mm, 29.85 ± 13.19mm, and 25.04 ± 12.32mm in RAQ, LAQ, RPQ and LPQ respectively. These results explained the results of Bakir et al. who found that the accuracy of Goodsell’s rules to predict the IO was more accurate in posterior fistulas (73%), which were shorter, than in anterior fistulas (52.4%)31. Shorter length of the posterior than in anterior fistulas is a significant point for success of surgery which may be more challenging in posterior midline than in lateral fistulas32.

Perianal fistula impairs the quality of life, and the patients may accept the risk of postoperative incontinence with fistulotomy33. A previous metanalysis evaluated the efficacy of fistulectomy compared to fistulotomy and reported that the two surgical methods have the same low rate of fecal incontinence with no significant difference in rate of fistula recurrence in low perianal fistula34. In the Hadhramout region, the only treatment method is surgery and most patient with a perianal fistula accept surgical treatment with good outcomes in most patients. The prognosis for the perianal fistula varies according to the etiology. With sphincter preserving surgery, perianal fistulas of cryptoglandular origin have 80% and 60% healing rates in simple and complex fistulas, respectively35. The challenge in management of perianal fistulas is to determine the course of the fistular tract between the IO and EO14. Short fistular tract and the short distance of IO from the anal verge as in the LPQ make diagnosis and surgery easier.

Ultimately, it is necessary to review the factors increasing the risk of perianal fistula formation, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, smoking, sedentary life, excessive intake of greasy and spicy food, and prolonged sitting on the toilet for defecation36. Sexually transmitted diseases are a risk factor, especially in immunosuppressed patients37. In total, 40%-60% of patients treated for an acute perianal abscess will eventually develop a perianal fistula26. After drainage of the perianal abscess, good management by in-hospital dressing with regular washing of the wound until closure of the abscess pouch decreases the risk of a perianal fistula6. Mocanu et al. reported that the incision and drainage of anorectal abscesses followed by an empiric 5 to 10-day course of antibiotics may avoid the morbidity of perianal fistula38. More studies about the methods of avoiding perianal sepsis to prevent abscess formation and subsequent perianal fistula are recommended.

Limitations

The study focused on description of low-type intersphincteric perianal fistulas using ultrasound imaging. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, no available clinical information about the patients especially the causes of perianal fistulas. This study was limited to the low intersphincteric fistula as the most common type of perianal fistula. High perianal fistulas were excluded due to decrease efficacy of ultrasound imaging in high fistulas where an MRI is preferred. TCUS is also limited in that it is less effective in high perianal fistulas. A previous study reported that EAUS was a relatively effective method in detecting perianal fistulas which may be more sensitive than MRI in detecting transsphincteric and intersphincteric fistulas. However, MRI was higher than endorectal ultrasonography in detecting suprasphincteric perianal fistulas39. TCUS is also limited by that it demands a high level of knowledge and skills, as it is operator dependent, and machine setting is necessary to achieve high image quality and avoid pitfalls of artifacts40, especially in the complex structure of the perineum region.

Future guidelines

Further studies about the possibility of using deep ultrasound transducers to diagnose high perianal fistulas is needed to solve the problem of the paucity of EAUS and MRI in rural regions of developing countries.

Conclusions

The study demonstrated that, the majority of patients diagnosed with low type intersphincteric perianal fistulas were young adult males. These fistulas typically feature a single tract with a solitary external and internal opening. The combination of a solitary tract, along with the short length and minimal distance of the internal opening from the anal verge, enhances surgical outcomes and reduces the risk of complications and recurrence associated with perianal fistulas. TCUS, when performed by an experienced operator, can be effectively utilized for the diagnosis and surgical planning of low-type perianal fistulas, with the offer of that it is a non-invasive, well-tolerated, and radiation-free imaging method.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- TCUS:

-

Transcutaneous ultrasound

- EO:

-

External opening

- IO:

-

Internal opening

- mm:

-

Millimeter

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- EAUS:

-

Endoanal ultrasonography

- ACMC:

-

Alsafwa Consultative Medical Center

- MHz:

-

Megahertz

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- LAQ:

-

Left anterior quadrant

- LPQ:

-

Left posterior quadrant

- RAQ:

-

Right anterior quadrant

- RPQ:

-

Right posterior quadrant

- HSD:

-

Honestly significant difference

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- AC:

-

Anal canal

References

Ramírez Pedraza, N. et al. Perianal fistula and abscess: An imaging guide for beginners. Radiographics 42, E208–E209. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.210142 (2022).

Sarveazad, A., Bahardoust, M., Shamseddin, J. & Yousefifard, M. Prevalence of anal fistulas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed. Bench. 15, 1–8 (2022).

Adegbola, S. O. et al. Burden of disease and adaptation to life in patients with Crohn’s perianal fistula: A qualitative exploration. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18, 370. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01622-7 (2020).

Gou, B. et al. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of percutaneous fistula contrast-enhanced ultrasound combined with transrectal 360° 3-D imaging and conventional transrectal ultrasound in complex anal fistula. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 48, 2154–2161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2022.06.013 (2022).

Zhao, W. W. et al. Precise and comprehensive evaluation of perianal fistulas, classification and related complications using magnetic resonance imaging. Am. J. Transl. Res. 15, 3674–3685 (2023).

Gokce, F. S. & Gokce, A. H. Can the risk of anal fistula development after perianal abscess drainage be reduced?. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 1992(66), 1082–1086. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.66.8.1082 (2020).

Saranovic, D., Barisic, G., Krivokapic, Z., Masulovic, D. & Djuric-Stefanovic, A. Endoanal ultrasound evaluation of anorectal diseases and disorders: Technique, indications, results and limitations. Eur. J. Radiol. 61, 480–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.07.033 (2007).

Varsamis, N. et al. Perianal fistulas: A review with emphasis on preoperative imaging. Adv. Med. Sci. 67, 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advms.2022.01.002 (2022).

Sharma, A. et al. Current imaging techniques for evaluation of fistula in ano: A review. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med 51, 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-020-00252-9 (2020).

Bhatt, S., Jain, B. K. & Singh, V. K. Multi detector computed tomography fistulography in patients of fistula-in-ano: An imaging collage. Pol. J. Radiol. 82, 516–523. https://doi.org/10.12659/PJR.901523 (2017).

Spinelli, A. et al. Imaging modalities for perianal Crohn’s disease. Curr. Drug Targets 13, 1287–1293. https://doi.org/10.2174/138945012802429723 (2012).

Kav, T. & Bayraktar, Y. How useful is rectal endosonography in the staging of rectal cancer?. World J. Gastroenterol. 16, 691–697. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i6.691 (2010).

Jabeen, N., Qureshi, R., Sattar, A. & Baloch, M. Diagnostic accuracy of short tau inversion recovery as a limited protocol for diagnosing perianal fistula. Cureus 11, e6398. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.6398 (2019).

Singh, A., Kaur, G., Singh, J. I. & Singh, G. Role of transcutaneous perianal ultrasonography in evaluation of perianal fistulae with MRI correlation. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 32, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1743111 (2022).

Hwang, J. Y. et al. Transperineal ultrasonography for evaluation of the perianal fistula and abscess in pediatric Crohn disease: Preliminary study. Ultrasonography 33, 184–190. https://doi.org/10.14366/usg.14009 (2014).

Carr, S. & Velasco, A. L. Fistula-in-Ano. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557517/ (2023).

Yu, Q., Zhi, C., Jia, L. & Li, H. Cutting seton versus decompression and drainage seton in the treatment of high complex anal fistula: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 12, 7838. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11712-9 (2022).

Sainio, P. Fistula-in-ano in a defined population. Incidence and epidemiological aspects. Ann. Chir. Gynaecol. 73, 219–224 (1984).

Sanchez-Haro, E. et al. Clinical characterization of patients with anal fistula during follow-up of anorectal abscess: a large population-based study. Tech. Coloproctol. 27, 897–907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-023-02840-z (2023).

Shirah, B. H. & Shirah, H. A. The impact of the outcome of treating a high anal fistula by using a cutting seton and staged fistulotomy on Saudi Arabian patients. Ann. Coloproctol. 34, 234–240. https://doi.org/10.3393/ac.2018.03.23 (2018).

Garg, P. Understanding and treating supralevator fistula-in-ano: MRI analysis of 51 cases and a review of literature. Dis. Colon Rectum 61, 612–621. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001051 (2018).

Shindhe, P. S. Management of rare, low anal anterior fistula exception to Goodsall’s rule with Kṣārasūtra. Anc. Sci. Life 33, 182–185. https://doi.org/10.4103/0257-7941.144624 (2014).

van Koperen, P. J., Horsthuis, K., Bemelman, W. A., Stoker, J. & Slors, J. F. Perianale fistels: veranderde inzichten met betreklking tot classificatie en diagnostiek, en een nieuwe behandelstrategie [Perianal fistulas: Developments in the classification and diagnostic techniques, and a new treatment strategy]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 152, 2774–2780 (2008) (in Dutch).

Amato, A. et al. Italian society of colorectal surgery. Evaluation and management of perianal abscess and anal fistula: A consensus statement developed by the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR). Tech. Coloproctol. 19, 595–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-015-1365-7 (2015).

Andreou, C., Zeindler, J., Oertli, D. & Misteli, H. Longterm outcome of anal fistula: A retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 10, 6483. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63541-3 (2020).

Varsamis, N. et al. Preoperative assessment of perianal fistulas with combined magnetic resonance and tridimensional endoanal ultrasound: A prospective study. Diagnostics (Basel) 13, 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13172851 (2023).

Chauhan, N. S., Sood, D. & Shukla, A. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) characterization of perianal fistulous disease in a rural based tertiary hospital of North India. Pol. J. Radiol. 81, 611–617. https://doi.org/10.12659/PJR.899315 (2016).

Joshi, A. R. & Siledar, S. G. Role of MRI in ano-rectal fistulas. Curr. Radiol. Rep. 2, 63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40134-014-0063-y (2014).

Chang, K. H. et al. A comparison of the usage of anal verge and dentate line in measuring distances within the rectum. Int. J. Surg. Open 1, 18–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijso.2016.02.004 (2015).

Sudoł-Szopińska, I., Kołodziejczak, M. & Aniello, G. S. A novel template for anorectal fistula reporting in anal endosonography and MRI: A practical concept. Med. Ultrason. 21, 483–486. https://doi.org/10.11152/mu-2154 (2019).

Bakir, Q. K., Noori, I. F. & Noori, A. F. Accuracy prediction of Goodsall’s rule for anal fistulas of crypotogladular origin, is still standing?. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond). 86(5), 2453–2457. https://doi.org/10.1097/MS9.0000000000001554 (2024).

Kim, H. C. & Simianu, V. V. Contemporary management of anorectal fistula. Surg. Open Sci. 2(17), 40–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sopen.2023.12.005 (2024).

Owen, H. A., Buchanan, G. N., Schizas, A., Cohen, R. & Williams, A. B. Quality of life with anal fistula. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 98, 334–338. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2016.0136 (2016).

Xu, Y., Liang, S. & Tang, W. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing fistulectomy versus fistulotomy for low anal fistula. Springerplus 5, 1722. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-3406-8 (2016).

Jimenez, M. & Mandava, N. Anorectal Fistula. [Updated 2023 Feb 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560657/ (2023).

Wang, D. et al. Risk factors for anal fistula: A case-control study. Tech. Coloproctol. 18, 635–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-013-1111-y (2014).

Assi, R., Hashim, P. W., Reddy, V. B., Einarsdottir, H. & Longo, W. E. Sexually transmitted infections of the anus and rectum. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 15262–15268. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i41.15262 (2014).

Mocanu, V. et al. Antibiotic use in prevention of anal fistulas following incision and drainage of anorectal abscesses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Surg. 217, 910–917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.01.015 (2019).

Akhoundi, N. et al. Comparison of MRI and endoanal ultrasound in assessing intersphincteric, transsphincteric, and suprasphincteric perianal fistula. J. Ultrasound. Med. 42, 2057–2064. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.16225 (2023).

Alsaedi, H. I., Krsoom, A. M., Alshoabi, S. A. & Alsharif, W. M. Investigation study of ultrasound practitioners’ awareness about artefacts of hepatobiliary imaging in Almadinah Almunawwarah. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 38, 1526–1533. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.38.6.5084 (2022).

Funding

The authors confirm that this research did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.A. formed the study concept, performed the data analysis and wrote the article. A.A.B. provided ultrasound examinations, data collection and interpretation. A.M.H. revised the clinical information of the article. F.H.A., A.A.Q., A.G., and M.G. revised the data analysis. O.M.A., W.A, F.A.E., T.S.D., and K.M.A. edited the language and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consents to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Alsafwa Consultative Medical Center (ACMC) in Almukalla city, Hadramout, Republic of Yemen (Approval Number: ACMC-10–23). Patient informed consents were waived by the institutional review board the research ethics committee of ACMC due to the retrospective nature of the study. However, all procedures related to this study were done in conformity with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013, and all applicable standards and laws.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alshoabi, S.A., Binnuhaid, A.A., Hamid, A.M. et al. Ultrasound assessment of low type intersphincteric perianal fistulas in Yemen. Sci Rep 15, 22117 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06284-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06284-3