Abstract

Vermicompost application can improve soil physical structure and increase soil nitrogen (N) sequestration, yet its specific impact on soil aggregates in relation to changes in organic N fractions remains underexplored, especially in protected vegetable fields. We compared the effects of vermicompost substitution (commercial organic fertilizer, COF; reduced COF + vermicompost, RCOF + VC; vermicompost, VC) on soil dry aggregate size distribution, aggregate stability, particulate organic N (PON) and mineral-associated organic N (MON) distributions within aggregates, as well as their interrelationships in a protected continuous tomato cropping system. Compared with COF, RCOF + VC was not beneficial for soil macro-aggregation and aggregate stability in 20–40 cm, leading to diminished physical protection and loss of organic N fractions. In comparison, VC had no significant influence on soil aggregate structure, while was effective in N retention by preventing organic N degradation, especially in 0–20 cm. In all treatments, most PON and MON (averaging 86.05%) were distributed in macro-aggregates, which played more important role in regulating the quality of soil agglomeration structure than micro-aggregates. Although differing in quantity, PON and MON within macro-aggregates functioned equally in macro-aggregation, whereas for aggregate stability, MON played a more pivotal role. Vermicompost (30000 kg hm− 2) can completely replace commercial organic fertilizer in terms of maintaining aggregate structure and occluded organic N fractions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the continuous growth of protected vegetable production and demand, the application of nitrogen (N) fertilizers has increased dramatically. However, excessive application of chemical N fertilizers has resulted in degradation of soil physical structure and loss of N nutrients, which severely impacts vegetable production and the sustainability of facility agriculture1,2,3. Applying organic fertilizer in combination with inorganic fertilizer is considered to be an effective solution because it benefits soil aggregation and organic N sequestration4. Over recent years, the industrial-scale feeding of earthworms has led to a significant increase in the production of vermicompost. It is increasingly being utilized as a soil conditioner and alternative fertilizing material5, owing to its high yield, rapid maturation, low price, and advantages in enhancing soil quality. Vermicompost is characterized by long-term stability without dispersion and compaction6, rich in organic nutrients and containing a large number of beneficial microorganisms, thereby meeting the urgent requirements for sustainable facility agriculture7.

Soil aggregates are the fundamental structure units that reflect soil quality. Their quantity distribution and stability significantly influence the transformation and maintenance of organic N fractions in soil8, with the extent of this influence varying according to aggregate size9,10. Generally, particulate organic N (PON) exhibits a higher turnover rate and is more sensitive to fertilization, whereas mineral-associated organic N (MON) is considered a pool with slower turnover rate due to the chemical-physical interaction with soil minerals11. But the PON occluded within smaller aggregates was found to turnover slowly due to the physical protection provided by micro-aggregates (< 0.25 mm)12, which is stronger than in macro-aggregates (> 0.25 mm)13,14. In return, PON and MON within aggregates can regulate soil particle agglomeration. Studies have also shown that both PON and MON in micro-aggregates can benefit macro-aggregation and prolong longevity of newly-formed macro-aggregates15, but the roles they play are quite different. Specifically, PON is speculated to indirectly influence soil aggregate stability by regulating the concentrations of MON within aggregates through organic decomposition, while MON exerts a direct influence16. However, so far, the relative importance of the specific roles played by PON and MON within different aggregate sizes has not been adequately quantified or ranked. Additionally, the direct and indirect effects (through its conversion to MON) of PON from various particle sizes have not been thoroughly evaluated and compared.

The application of vermicompost has been reported to improve soil physical status, including decreased bulk density, increased aggregate formation and stability17,18. The improvement can be related to the increase in soil organic matter content, promoted growth and development of plant roots, and boosted microbial populations and metabolic activities, all of which function positively in aggregation19,20. However, the application effects of vermicompost on different organic N fractions within aggregate structure and their distributions remain underexplored, especially in protected continuous vegetable fields. Furthermore, previous studies have primarily focused on the fertilization effects of vermicompost on the storage of different organic C fractions within aggregates, which are mostly associated with the mechanisms of soil particle agglomeration and stabilization21,22. Few studies, however, have explored the responses of organic N fractions, which are also crucial for soil physical structure and even more important for plant morphogenesis. In addition, previous conclusions are typically drawn by comparing the substitution effects of organic fertilizers with those of chemical inorganic fertilizers23,24, which can lead to inaccurate assessments due to the variable outcomes of chemical inorganic fertilization (positive or negative)25,26.

The objective of this study was to: (1) compare the effects of vermicompost as partial or complete replacements for commercial organic fertilizers on soil aggregate size distribution and stability parameters; (2) investigate the effects of vermicompost application on aggregate-associated organic N fractions and verify the repository path of exogenous organic N; (3) evaluate the correlations between organic N fractions within aggregates and soil aggregate stability, and discuss the regulatory mechanisms involved. We hypothesized that, compared with commercial organic fertilization, partial and complete vermicompost substitution would enhance soil macro-aggregation, aggregate stability, and the concentrations of organic N fractions within macro-aggregates. Specifically, the concentration of MON rather than PON would play a dominant role in aggregate stabilization. The results would provide a basis for formulating alternative organic fertilization strategies that are sustainable, economical and environmentally friendly for use in facilities.

Materials and methods

Site description

We conducted a field study in Liugu Town (35°50′ N, 114°76′ E), Hua County, Henan Province, China between 2022 and 2023 (Fig. 1). This location has a sub-humid warm temperate continental monsoon climate, with an annual average temperature of 13.7 °C and a total rainfall of 634.3 mm (maicnly concentrated from June to September). The average duration of annual sunshine is 2161 h. The soil is classified as a new alluvial soil (according to Soil Taxonomy of the USA) considering that it has developed from modern river alluvial sediments, with a sandy loam texture. The field trial was set up in a well-drained area where tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is cropped twice on an annual basis. At the start of the experiment in July 2022, the soil had a pH of 6.7 (1:1 soil: water), the soil organic matter content was 13.7 g kg− 1, total N was 1.4 g kg− 1, available phosphorus and available potassium were 78.4 mg kg− 1 and 151.6 mg kg− 1, respectively. Soil bulk density was 1.2 g cm− 3.

Location of the experimental site. The two pictures above are screenshots taken from Google’s online satellite map (http://www.gditu.net/, 2024, December 1). Copyright © 2024 Google’s online satellite map Inc. All rights reserved. When using Google satellite maps, we strictly abide by copyright laws and regulations, and there is no infringement of Google’s copyright and intellectual property rights.

Field experimental design

We designed the experiment to feature three treatments: (1) the basal application of commercial organic fertilizer (COF); (2) reduced chemical organic fertilizer (by 30%) combined with vermicompost, both being applied basally (RCOF + VC); (3) the basal application of vermicompost (VC). Equal amounts of chemical inorganic fertilizers were also applied for each treatment. The same amount of organic-derived N was applied for the COF and RCOF + VC treatments (Table 1). The contents of organic matter, total N, total P, and total K in the commercial organic fertilizer (Ziniu organic fertilizer, Inner Mongolia Bayan Nuer City Deyuan fertilizer Co., LTD) were 55%, 8%, 3%; and 1%, respectively. For vermicompost, the values were 30%, 0.64%, 1.1%, and 0.96%, respectively. The vermicompost was produced by feeding earthworms with sewage sludge (produced by Xinxiang Yinongda Biotechnology Company).

Each treatment was replicated for three times in a randomized block design, resulting in the establishment of 12 field-scale fertilization plots. The plot size was 3 m × 7 m, and a buffer zone with a width of 2 m was established around each plot. All organic fertilizers were incorporated into the soil at a depth of 0–30 cm using conventional tillage prior to tomato transplanting. Tomatoes were transplanted at a density of 30,000 plants per hectare. All plant straws (after the tomatoes had been pulled) were crushed and returned to the field. Other management strategies practiced during the growth of tomato plants were in line with local farming practices.

Soil sampling and analysis

Immediately after the tomato pulling in July 2023, five soil cores from topsoil (0–30 cm) were randomly collected from each plot and then uniformly mixed as a composite sample. Following the removal of stones and visible plant residues, the sampled soil was air-dried and used for soil particle classification and the determination of soil PON and MON in each particle size fraction.

After removing soil clods larger than 8 mm, the aggregate size distribution was determined by shaking soil samples for 5 min in a stack of sieves (2 mm, 0.25 mm) in a tapping sieve shaker (Gilson Company Inc., Lewis Center, OH, USA). 100 g of air-dried soil samples were placed in the middle of the top sieve. Soil aggregates were divided into large macro-aggregates (> 2 mm), small macro-aggregates (0.25–2 mm), and micro-aggregates (< 0.25 mm).

The concentrations of PON and MON within aggregates were determined by methodology previously described by Paye et al.27. In brief, a 5-g separated aggregate sample was shaken with 30 ml of 0.5% sodium hexametaphosphate solution for 18 h. All dispersed samples were then transferred to a 0.053 mm sieve. The components remaining on the sieve were particulate organic matter, while those that passed through the sieve were mineral-associated organic matter. The collected organic components were then dried at 60℃ and sieved (0.15 mm). The total N content of the particulate organic matter and the mineral-associated organic matter were then analyzed by the Kjeldahl digestion method28.

Calculations and statistical analysis

MR0.25 indicated the mass proportions of aggregates > 0.25 mm.

Mean weight diameter (MWD), geometric mean diameter (GMD) and Fractal dimension (D) were indices used to evaluate the stability of soil aggregates. They were calculated according to the formula below29,30:

\(\:\text{MWD}=\sum\nolimits_{{i = 1}}^{n}\)Ȓi(Mi / Mt).

\(\:\text{G}\text{M}\text{D}\text=\text{e}\text{x}\text{p}\:[\sum\:_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}\text{M}\text{i}\text{l}\text{n}\)Ȓ\(\sum\nolimits_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}\text{M}\text{i}\)

where Mi was the mass (g) of a certain aggregate remaining on the sieve, and Mt was the total mass of all aggregates. Ȓi was the mean diameter (mm) between two sieves. n indicated the number of aggregate fractions (> 2 mm, 0.25–2 mm and < 0.25 mm).

D=3-log [M(r<Ȓi) / log(Ȓi/Rmax).

where M(r<Ȓi) represented the sum aggregate mass (g) with particle size less than Ȓi. Rmax was the maximum diameter (mm) of a certain fractioned aggregates. Liner regression was used to calculate D by the least-square method.

N management or mobility index (NMI), which reflects the increase of soil organic N and the proportion of labile N in relation to the control31, can indicate the effects of fertilizer treatments on the stability of soil N stocks. It was calculated according to that of C32:

N management index (NMI) = NPI×LI×100.

The N pool index (NPI) = SONf / SONc.

The lability index (LI) = PONf / (PONc/MONc).

Where SONf and SONc represented the concentration of soil organic N in the fertilized treatment and control, respectively. PONf was the N concentration of the particle organic matter in fertilized treatment; PONc and MONc were the N concentrations of particle organic matter and mineral-associated organic matter in the control, respectively.

Statistical analyses were performed with Excel 2007 (Microsoft, Redmond, USA) and SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to test the differences between the fertilizer treatments following a homogeneity test of variance. Least significant different (LSD) analysis, at the significance level of P < 0.05, was used to assess the differences between treatments. Pearson correlation and linear regression analysis was conducted to disclose the relationships between soil aggregates stabilization and the PON, MON within aggregates. Path coefficients (direct and indirect) were calculated to identify the main pathways of influence. Data are all presented as means (n ≥ 3).

Results

Soil aggregate size distribution and stability

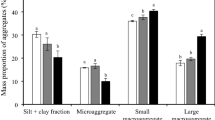

For all treatments, large macro-aggregates (> 2 mm) dominated in mass proportions (average 51.38%), followed by small macro-aggregates (0.25–2 mm) and micro-aggregates (< 0.25 mm) (average 28.67% and 19.95%) (Table 2). The effect of vermicompost application changed in different soil layers. In 0–20 cm, compared with COF, neither partial nor absolute vermicompost application had a significant influence on the mass proportions of fractioned aggregates. While in 20–40 cm, the mass proportions of large macro-aggregates and micro-aggregates were significantly (P < 0.05) increased by both VC and RCOF + VC, both at the expense of small macro-aggregates. As a whole, the mass proportions of aggregates > 0.25 mm (MR0.25) was not significantly changed by RCF + VC in 0–20 cm, but in 20–40 cm, it was significantly (P < 0.05) reduced. VC had no significant influence on MR0.25 in either of the soil layers.

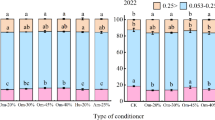

The values of MWD and GMD in 0–20 cm were larger than those in 20–40 cm for all treatments (Fig. 2a, b). In 0–20 cm, compared with COF, vermicompost application had no significant influence on the values of MWD, GMD, and D (Fig. 2). However, in 20–40 cm, RCOF + VC significantly (P < 0.05) decreased GMD whereas increased D value, both of which were not significantly changed by VC. The VC treatment significantly (P < 0.05) increased MWD value in 20–40 cm. This showed that partial vermicompost substitution was disadvantageous for aggregate stability.

Effects of fertilizer treatments on soil aggregate stability characteristics. Aggregate stability characteristics: MWD, mean weight diameter; GMD, geometric mean diameter; D, fractal dimension. Different lowercase letters in the same group indicate significant (P < 0.05) differences between the fertilizer treatments.

PON and MON distributions within aggregates and their contributions

Compared with COF, RCOF + VC significantly reduced the PON and MON concentrations in all aggregate sizes (P < 0.05, except for small macro-aggregates in 20–40 cm) (Fig. 3a-f), and consequently, the concentrations of soil total PON (the sum of all fractioned aggregates) and total MON.

The concentrations of soil PON and MON within aggregates under different fertilizer treatments. * indicates there are significant (P < 0.05) differences in both PON and MON concentrations (of the RCOF + VC or VC treatment) when compared with the COF treatment, whereas ns indicates no significant difference when compared with the COF treatment.

The effects of VC varied with both aggregate sizes and soil layers: in large macro-aggregates, the concentration of PON was significantly (P < 0.05) increased by VC in 0–20 cm, whereas in 20–40 cm, it was markedly (P < 0.05) decreased; the concentration of MON showed the opposite trend. In small macro-aggregates, both the PON and MON concentrations were significantly (P < 0.05) increased in two layers. As a whole, the PON and MON concentrations in macro-aggregates were significantly (P < 0.05) increased by VC in 0–20 cm, but in 20–40 cm, they were not significantly changed.

The distributions of PON and MON within aggregates and whole soil were not significantly affected by vermicompost application (except for micro-aggregates in 0–20 cm) (Fig. 4a-h). In all aggregates, compared with PON, MON completely dominated due to its large mass proportions (average 74.24%), regardless of their specific concentrations (Fig. 4a-f).

The distributions of PON and MON in aggregates under different fertilizer treatments. * indicates there are significant (P < 0.05) differences in both PON and MON distributions (of the RCOF + VC or VC treatment) when compared with the COF treatment, whereas ns indicates no significant difference when compared with the COF treatment.

In both soil layers, the values of NPI, LI and NMI in VC were significantly (P < 0.05) higher than those in the RCOF + VC treatment (Table 3). The higher LI values were in accordance with the higher concentrations and distributions of the labile fraction (PON) in macro-aggregates (Figs. 3 and 4b, c, e and f). In 0–20 cm, the value of NMI in the VC treatment was larger than the reference value (100), indicating that absolute vermicompost application was effective in preventing the degradation of N compounds. The values of LI and NMI were significantly (P < 0.05) higher in 0–20 cm than in 20–40 cm, regardless of the fertilizer treatments, indicating a greater effect of fertilization on N retention in surface soil.

For all treatments, the contributions of PON or MON from macro-aggregates were dominant (> 81.75%) (Fig. 5). Compared with COF, RCOF + VC significantly (P < 0.05) increased the contributions of PON and MON from macro-aggregates in both soil layers. Also, VC significantly (P < 0.05) increased the contributions of PON and MON from macro-aggregates in 0–20 cm, but in 20–40 cm, it had no significant influence.

Soil aggregate characteristics as influenced by PON and MON

Our analysis identified significant (P < 0.05) or highly significant (P < 0.01) positive correlations between soil total PON, MON and MR0.25, MWD, GMD values, whereas negative correlations between soil total PON, MON and D values (Fig. 6). Except for the MON in small macro-aggregates, PON and MON concentrations in aggregates were significantly (P < 0.05) positively correlated with MWD and GMD values. This showed that soil macro-aggregation and aggregate stability were correlated with or regulated by PON and MON concentrations within aggregates.

Correlations between soil organic N fractions and aggregate stability characteristics. PON1, PON2 and PON3 indicate the particulate organic N in aggregates < 0.25 mm, between 0.25 mm and 2 mm, and > 2 mm, respectively. While MON1, MON2 and MON3 indicate the mineral associated organic N in correspongding aggregate size. PON and MON represent soil total PON and MON concentrations. MR0.25 indicates the mass proportions of aggregates > 0.25 mm in size. * and ** indicate significant (P < 0.05) and highly significant (P < 0.01) correlations between two indicators.

Stepwise linear regression revealed that MR0.25 and MWD values were most positively regulated by the concentrations of MON and PON in large macro-aggregates (Table 4). MON in large macro-aggregates also had the largest positive regulatory effect on GMD value. But they adjusted the D value negatively, indicating that PON and MON in large macro-aggregates played a dominant role in promoting macro-aggregation and aggregate stability. PON in small macro-aggregates had the largest positive regulation on the D value but regulated MR0.25 negatively. The regulation of PON and MON in aggregates < 0.25 mm was inferior to that in larger aggregates, especially the aggregates that were > 2 mm.

The direct path coefficients of PON on macro-aggregation and aggregate stability were larger than the indirect path coefficients (Table 5), indicating that the stability of aggregates relied more on the regulation of PON within large macro-aggregates instead of its conversion to MON.

Discussion

Soil aggregate distributions as influenced by vermicompost application

The application of organic amendments is increasingly gaining popularity in sustainable crop production and soil degradation control33,34. Compared with chemical inorganic fertilization only, combined or pure organic fertilization has been verified to improve the physical structure of soil by increasing macro-aggregation35,36. However, existing conclusions regarding the substitution effects of organic fertilizers may be inaccurate due to the complex and variable influences of inorganic fertilization on soil aggregation. Some researches pointed that long-term inorganic N application reduced soil aggregation and aggregate stability25, potentially leading to an overestimation of the effects of organic fertilization. In contrast, other researches claimed that balanced inorganic fertilization may improve aggregation37, with no additional benefits obtained with organic fertilizers substitution26. There are even studies comparing the fertilization effects of organic materials with a control without any fertilizer23,38, which further overestimate the benefits of organic fertilization. Consequently, it’s necessary to re-examine the effects of organic fertilization objectively by comparing with organic fertilizer, which is more comparable due to their similar substance compositions and functions.

In this study, commercial organic fertilization was used as a control to verify the effects of vermicompost substitution. In all the fertilizer treatments, macro-aggregates were dominant in mass proportions (average 80.05%). Compared with COF, although larger amounts of organic matter were added in RCOF + VC, it was not beneficial to soil macro-aggregation and aggregate stability in 20–40 cm. This is contrary to our original assumption and the existing conclusion that the increased organic nutrients application can gain a higher percentage of macro-aggregates and increased aggregate stability39,40. Moreover, the larger amount of potassium in RCOF + VC was supposed to decrease clay dispersion and improve aggregate stability41. The disadvantages could be due to the superimposed excessive soluble salts (both from commercial organic fertilizer and vermicompost) such as Na+ and Ca2+ (about 2% and 8% in the applied commercial organic fertilizer and vermicompost, respectively), which are negatively correlated with the aggregate stability42. Besides, the history of long-term organic fertilization may weaken the positive effects of newly applied vermicompost. In future research, the adverse influencing factors should be excluded before the combined application of commercial organic fertilizer and vermicompost.

Compared with COF, absolute vermicompost application (VC) had no significant influence on the mass distributions and stability of aggregates in both soil layers, suggesting vermicompost to be a good substitute for commercial organic fertilizer without any disadvantages on macro-aggregation and stability characteristics. This is likely due to a combination of three reasons. First, the abundant polysaccharides and humid acids in vermicompost that act as a cementing substance to bond soil particles and increase aggregate stability43. Secondly, the abundant C sources that can promote the growth and metabolism of bacteria and fungi, who’s metabolites (such as polysaccharides, extracellular complexes, and proteins) can produce a cementation effect on soil particles44. Thirdly, the improvement of soil structure with vermicompost fertilization is very helpful for crop root development and fungal hyphae growth, which in turn facilitate macro-aggregation and promote stabilization. Unfortunately, the absence of data related to microorganisms (e.g., microbial biomass, community composition, enzyme activities) and plant roots (root length, surface area, biomass, exudate) in this study greatly limits the interpretation of the result. In future studies, quantification of these indicators would help to clarify the influencing mechanisms involved.

Previous studies have shown that increased N fertilization under straw returning can improve soil aggregation and stability42. But in the VC treatment, with the tomato straw crushed and returned to the field after plant pulling, the reduced total N application (a reduction of 70% in comparison with COF and RCOF + VC) did not significantly reduce the mass proportions of dry sieved macro-aggregates and aggregate stability, indicating that the amount of N from chemical inorganic fertilizer was large enough as a base, without any external advantages observed under additional N increase. Alternatively, the result may be due to the discrepancy of organic and inorganic N sources in regulating soil agglomeration structure45. Furthermore, the positive effects of vermicompost on soil physical structure may offset part of the disadvantages associated with total N reduction. Overall, the amount of 30,000 kg hm− 2 vermicompost in conjunction with inorganic fertilizers is appropriate for maintaining soil structural sustainability in the multi-year continuous vegetable cropping facility. But an excessive-application of vermicompost should be avoided, considering that the high concentrations of soluble salts available in it may disperse soil aggregates.

Organic N fractions within aggregates as influenced by vermicompost application

PON and MON are two organic N fractions in soil with distinct stability and turnover rates. These differences may be further amplified by the function of different aggregates46. In the present study, the contributions of PON or MON from macro-aggregates completely dominated (average 86.05%), regardless of the fertilizer treatments, indicating that most N are distributed in the macro-aggregate occluded fractions47. But compared with PON, MON dominated in all aggregate sizes due to its large mass proportions, regardless of their specific concentrations. This suggests MON in macro-aggregates as a primary fate and reservoir pool for exogenous organic N. Studies have shown that the fates of exogenous organic amendment change with their kinds. Generally, water soluble organic inputs are expected to stabilize through chemical binding to minerals, forming mineral-associated organic matter before or after microbial transformation, while structural inputs are expected to stabilize as particulate organic matter via protection within the aggregate structure48. In protected vegetable fields, with the long-term annual large application of soluble organic inputs, the basic storage of MON within aggregates, especially in macro-aggregates are supposed to be higher. The higher concentrations and distributions of PON within macro-aggregates in VC than COF, especially in surface soil, can also verify the different fates of water soluble chemical organic fertilizer and vermicompost. The former contributed more to the MON pool, while the latter contributed more to the PON pool. In future studies, the transformation pathways of different exogenous N (water soluble organic inputs or structural inputs, organic or inorganic) in soil can be further traced through the application of 15N isotopically labeled fertilizers.

The substitution of organic fertilizers can generally increase the amounts of N storage in all aggregates fractions, when compared with controls without any fertilizer or chemical inorganic fertilization only49,50. But in the present study, when compared with COF, the concentrations of both PON and MON within all aggregates were substantially reduced by RCOF + VC, with the micro-aggregates showing an almost complete loss. According to existing research51, the loss of PON in micro-aggregates was associated with the destruction of transient organic cementing agents, thus resulting in the collapse of macro-aggregates. In addition, the destruction would lead to an exposure of PON, making it more available to rapid oxidation and microbial attack. So the disadvantages of RCOF + VC on soil macro-aggregation and aggregate stability, especially in 20–40 cm, would result in a decreased physical protection of PON and MON within aggregates, thereby reducing their amounts. The degradation of aggregates is therefore considered to be an important cause of loss for soil organic N fractions in soil.

Compared with COF, VC significantly increased the storage of PON and MON in macro-aggregates. Also, the NMI of VC treatment in 0–20 cm exceeded the reference value (100), indicating that vermicompost application was effective in N retention and preventing the degradation of N compounds52. On the one hand, the increased N storage can be associated with the pronounced mineralization of organically bound nutrients that act as binding agents for soil particles. On the other hand, this may be due to the promoted macro-aggregation, and root system biomass, both of which can enhance the physical protection of soil organic matter46. In addition, the increased microbiogenic metabolites that benefit from the abundant C sources and physiologically active substances in vermicompost can facilitate the formation of stable macro-aggregates53, thus reducing the mineralization and losses of PON and MON within aggregates.

Soil aggregation and stability as regulated by PON and MON

Soil macro-aggregation and aggregate stability were significantly correlated with PON and MON concentrations within aggregates, which coincides with former researches54 and indicates that PON and MON within aggregates may regulate the formation of soil aggregates directly or indirectly. But their intensity of regulation changed with aggregate sizes. Specifically, the regulation effects of PON and MON from aggregates < 0.25 mm was inferior to that from larger aggregates, especially that from aggregates > 2 mm. Both PON and MON concentrations in large macro-aggregates played a dominant role in improving macro-aggregation and aggregate stability, regardless of the fertilizer treatments, indicating that organic N in macro-aggregates are critical for the quality of soil agglomeration structure. But according to previous studies, the key organic N in action should be in micro-aggregates within macro-aggregates15. So more detailed fractions should be conducted in future research to verify their specific roles.

Compared with PON, MON was the dominant organic N fraction within aggregates due to its larger mass proportions. However, PON and MON played nearly equivalent roles in terms of promoting soil macro-aggregation. Nevertheless, in terms of comprehensively increasing aggregates stability (increased MWD and GMD, but decreased D), MON played a more pivotal role. The MON fraction is believed to contain significant quantities of fungal cell wall residues (supported by the relatively large amounts of mycorrhizal fungal hyphae with organic amendment) that may contribute to the binding of micro-aggregates and enhance aggregate stability55. Aoyama et al.16 had hypothesized that exogenous organic amendment first entered the soil primarily as PON, and then, during decomposition, was transformed into MON within aggregates, thereby contributing to aggregate stabilization. So PON is speculated to indirectly affect aggregate stability by influencing MON concentrations through organic matter decomposition. Further path analysis confirmed the hypothesis. However, the results showed that the indirect impact of PON on aggregate stability via MON was not dominant, given the larger direct path coefficients. Most PON in large macro-aggregates continue to play a direct role in regulating aggregate stability. The sum of direct and indirect path coefficients in Table 4 was less than the correlation coefficient, indicating that PON in large macro-aggregates also affect soil aggregate stability through other ways. The application of isotope tracer technology will help to explain the changes of organic N fractions and identify the specific pathway of action in future research.

Conclusions

Compared with COF, RCOF + VC was not beneficial for soil macro-aggregation and aggregate stability at the 20–40 cm depth, leading to reduced physical protection and lower concentrations of PON and MON. In comparison, VC had no significant disadvantages on soil aggregation and stability characteristics and was effective in N retention and can prevent degradation of N compounds within aggregates, especially in 0–20 cm. The majority of PON and MON were distributed in macro-aggregates. The positive regulation of PON and MON from macro-aggregates on the quality of soil agglomeration structure was larger than that from smaller aggregates. Although differing significantly in quantity (MON dominated), PON and MON within macro-aggregates functioned almost equivalent in promoting soil macro-aggregation. Whereas for aggregate stability, MON in macro-aggregates played a more pivotal role. For MON, we identified a direct regulatory role rather than an indirect role via its conversion to MON.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- N:

-

nitrogen

- COF:

-

commercial organic fertilizer

- RCOF + VC:

-

reduced commercial organic fertilizer + vermicompost

- VC:

-

vermicompost

- PON:

-

particulate organic nitrogen; MON, mineral-associated organic nitrogen

- MR0.25 :

-

mass proportions of aggregates > 0.25 mm

- MWD:

-

mean weight diameter

- GMD:

-

geometric mean diameter

- D:

-

fractal dimension

- NMI:

-

nitrogen management index

- NPI:

-

nitrogen pool index

- LI:

-

lability index

References

Hefner, M., Sorensen, J. N., de Visser, R. & Kristensen, H. L. Sustainable intensification through double-cropping and plant-based fertilization: production and plant-soil nitrogen interactions in a 5-year crop rotation of organic vegetables. Agroecol Sust Food. 46, 1118–1144 (2022).

Pan, F. F. et al. Fertilization practices: optimization in greenhouse vegetable cultivation with different planting years. Sustainability 14, 7543 (2022).

Ju, X. T., Gao, Q., Christie, P. & Zhang, F. S. Interception of residual nitrate from a calcareous alluvial soil profile on the North China plain by deep-rooted crops: a 15N tracer study. Environ. Pollut. 146, 534–542 (2007).

Chen, H. Q. et al. Maize straw-based organic amendments and nitrogen fertilizer effects on soil and aggregate-associated carbon and nitrogen. Geoderma 443, 116820 (2024).

Ibrahim, M. M., Mahmoud, E. K. & Ibrahim, D. A. Effects of vermicompost and water treatment residuals on soil physical properties and wheat yield. Int. Agrophys. 29, 157–164 (2015).

Lim, S. L., Wu, T. Y., Lim, P. N. & Shak, K. P. Y. The use of vermicompost in organic farming: overview, effects on soil and economics. J. Sci. Food Agr. 95, 1143–1156 (2015).

Oyege, I. & Balaji Bhaskar, M. S. Effects of vermicompost on soil and plant health and promoting sustainable agriculture. Soil. Syst. 7, 101 (2023).

Mustafa, A. et al. Soil aggregation and soil aggregate stability regulate organic carbon and nitrogen storage in a red soil of Southern China. J. Environ. Manage. 270, 110894 (2020).

Wang, Y. L. et al. The potential for soil C sequestration and N fixation under different planting patterns depends on the carbon and nitrogen content and stability of soil aggregates. Sci. Total Environ. 897, 165430 (2023).

Tian, S. et al. Organic fertilization promotes crop productivity through changes in soil aggregation. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 165, 108533 (2022).

Lavallee, J. M., Soong, J. L. & Cotrufo, M. F. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Global Change Biol. 26, 261–273 (2020).

Besnard, E., Chenu, C., Balesdent, J., Puget, P. & Arrouays, D. Fate of particulate organic matter in soil aggregates during cultivation. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 47, 495–503 (1996).

Kamran, M. et al. Effect of reduced mineral fertilization (NPK) combined with green manure on aggregate stability and soil organic carbon fractions in a fluvo-aquic paddy soil. Soil. Till Res. 211, 105005 (2021).

De Gryze, S., Six, J., Brits, C. & Merckx, R. A quantification of short-term macroaggregate dynamics: influences of wheat residue input and texture. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 37, 55–66 (2005).

Six, J. & Paustian, K. Aggregate-associated soil organic matter as an ecosystem property and a measurement tool. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 68, A4–A9 (2014).

Aoyama, M., Angers, D. A. & N’dayegamiye, A. Particulate and mineral-associated organic matter in water-stable aggregates as affected by mineral fertilizer and manure applications. Can. J. Soil. Sci. 79, 295–302 (1999).

Yang, Z. et al. Vermicompost addition improved soil aggregate stability, enzyme activity, and soil available nutrients. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nut. 24, 6760–6770 (2024).

Li, W. L. et al. Evaluating the effects of formation and stabilization of opal/sand aggregates with organic matter amendments. J. Environ. Manage. 337, 117749 (2023).

Mulatu, G. & Bayata, A. Vermicompost as organic amendment: effects on some soil physical, biological properties and crops performance on acidic soil: a review. Front. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 66–73 (2024).

Zhang, M. N. et al. Microbial regulation of aggregate stability and carbon sequestration under long-term conservation tillage and nitrogen application. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 44, 74–86 (2024).

Mustafa, A. et al. Long-term fertilization enhanced carbon mineralization and maize biomass through physical protection of organic carbon in fractions under continuous maize crop. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 165, 103971 (2021).

Li, T. et al. Contrasting impacts of manure and inorganic fertilizer applications for nine years on soil organic carbon and its labile fractions in bulk soil and soil aggregates. Catena 194, 104739 (2020).

Mangalassery, S., Kalaivanan, D. & Philip, P. S. Effect of inorganic fertilizers and organic amendments on soil aggregation and biochemical characteristics in a weathered tropical soil. Soil. Till Res. 187, 144–151 (2019).

Ferreras, L., Gomez, E., Toresani, S., Firpo, I. & Rotondo, R. Effect of organic amendments on some physical, chemical and biological properties in a horticultural soil. Bioresource Technol. 97, 635–640 (2006).

Blanco-Canqui, H., Ferguson, R. B., Shapiro, C. A., Drijber, R. A. & Walters, D. T. Does inorganic nitrogen fertilization improve soil aggregation? Insights from two long‐term tillage experiments. J. Environ. Qual. 43, 995–1003 (2014).

Doan, T. T., Ngo, T. P., Tumpel, C., Nguyen, V. B. & Jourquet, P. Interactions between compost, vermicompost and earthworm influence plant growth and yield: a one year greenhouse experiment. Sci. Hortic. 160, 148–154 (2013).

Paye, W. S., Thapa, V. R. & Ghimire, R. Limited impacts of occasional tillage on dry aggregate size distribution and soil carbon and nitrogen fractions in semi-arid drylands. Int. Soil. Water Conse. 12, 96–106 (2024).

Lu, R. K. Analysis Methods of Soil Agricultural Chemistry (ed. Lu, R.K.) 147–149 Beijing, (1999).

Tyler, S. W. & Wheatcraft, S. W. Fractal scaling of soil particle-size distributions: analysis and limitations. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 56, 362–369 (1992).

Kemper, W. D. & Rosenau, R. C. Aggregate stability and size distribution, In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 1 Physical and mineralogical methods. 5, 425–442 (1986).

Oliveira, D. M. et al. Assessing labile organic carbon in soils undergoing land use change in brazil: A comparison of approaches. Ecol. Indic. 72, 411–419 (2017).

Guimarães, D. V. et al. Dynamics and losses of soil organic matter and nutrients by water erosion in cover crop management systems in Olive groves, in tropical regions. Soil. Till Res. 209, 104863 (2021).

Matisti, M., Dugan, I. & Bogunovic, I. Challenges in sustainable agriculture-the role of organic amendments. Agriculture 14, 643 (2024).

Pingthaisong, W., Blagodatsky, S., Vityakon, P. & Cadisch, G. Mixing plant residues of different quality reduces priming effect and contributes to soil carbon retention. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 188, 109242 (2024).

Du, S. et al. Effects of organic fertilizer proportion on the distribution of soil aggregates and their associated organic carbon in a field mulched with gravel. Sci. Rep. 12, 11513 (2022).

Bidisha, M., Joerg, R. & Yakov, K. Effects of aggregation processes on distribution of aggregate size fractions and organic C content of a long-term fertilized soil. Eur. J. Soil. Biol. 46, 365–370 (2010).

Rasool, R., Kukal, S. S. & Hira, G. S. Soil organic carbon and physical properties as affected by long-term application of FYM and inorganic fertilizers in maize-wheat system. Soil. Till Res. 101, 31–36 (2008).

Gautam, A., Guzman, J., Kovacs, P. & Kumar, S. Manure and inorganic fertilization impacts on soil nutrients, aggregate stability, and organic carbon and nitrogen in different aggregate fractions. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 68, 1261–1273 (2022).

Sarker, T. C. et al. Soil aggregation in relation to organic amendment: a synthesis. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nut. 22, 2481–2502 (2022).

Ozlu, E. & Kumar, S. Response of soil organic carbon, pH, electrical conductivity, and water stable aggregates to long-term annual manure and inorganic fertilizer. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 82, 1243–1251 (2018).

Phocharoen, Y., Aramrak, S., Chittamart, N. & Wisawapipat, W. Potassium influence on soil aggregate stability. Commun. Soil Sci. Plan. 49, 2162–2174 (2018).

Xie, W. J. et al. Coastal saline soil aggregate formation and salt distribution are affected by straw and nitrogen application: A 4-year field study. Soil. Till Res. 198, 104535 (2020).

Liu, M. L., Wang, C., Wang, F. Y. & Xie, Y. J. Vermicompost and humic fertilizer improve coastal saline soil by regulating soil aggregates and the bacterial community. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 65, 281–293 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Linkage of aggregate formation, aggregate-associated C distribution, and microorganisms in two different-textured ultisols: A short-term incubation experiment. Geoderma 394, 114979 (2021).

Abiven, S., Menasseri, S. & Chenu, C. The effects of organic inputs over time on soil aggregate stability- a literature analysis. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 41, 1–12 (2009).

Ontl, T. A., Cambardella, C. A., Schulte, L. A. & Kolka, R. K. Factors influencing soil aggregation and particulate organic matter responses to bioenergy crops across a topographic gradient. Geoderma 255, 1–11 (2015).

Liu, Z. J. et al. Soil aggregation is more important than mulching and nitrogen application in regulating soil organic carbon and total nitrogen in a semiarid calcareous soil. Sci. Total Environ. 854, 158790 (2023).

Even, R. J. & Cotrufo, M. F. The ability of soils to aggregate, more than the state of aggregation, promotes protected soil organic matter formation. Geoderma 442, 116760 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Reducing nitrogen fertilizer usage coupled with organic substitution improves soil quality and boosts tea yield and quality in tea plantations. Journal of the science of food and agriculture. J. Sci. Food Agr. 105, 1228–1238 (2024).

Cui, H. et al. Soil aggregate-driven changes in nutrient redistribution and microbial communities after 10-year organic fertilization. J. Environ. Manage. 348, 119306 (2023).

Bongiovanni, M. D. & Lobartini, J. C. Particulate organic matter, carbohydrate, humic acid contents in soil macro-and microaggregates as affected by cultivation. Geoderma 136, 660–665 (2006).

Geraei, D. S., Hojati, S., Landi, A. & Cano, A. F. Total and labile forms of soil organic carbon as affected by land use change in Southwestern Iran. Geoderma 7, 29–37 (2016).

Yang, Y., Zhang, Y. G., Yu, X. X. & Jia, G. D. Soil microorganism regulated aggregate stability and Rill erosion resistance under different land uses. Catena 228, 107176 (2023).

Pikul, J. L., Osborne, S., Ellsbury, M. & Riedell, W. Particulate organic matter and water-stable aggregation of soil under contrasting management. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 71, 766–776 (2007).

Yang, W. et al. Compost addition enhanced hyphal growth and sporulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi without affecting their community composition in the soil. Front. Microbiol. 9, 169 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all authors for their efforts. Our work was supported by the major scientific and technological project of Henan Province (241100110200), the bulk vegetable industry technical system project of Henan Province (HARS-22-07-G6).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pan wrote the manuscript. Others were involved in data processing and paper revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Other statement

We declare that no AI-related software or means were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, F., Zhang, J., Tang, J. et al. Soil aggregate and organic nitrogen distributions as influenced by vermicompost application in vegetable greenhouse. Sci Rep 15, 22407 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06286-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06286-1