Abstract

Repeated hydraulic fracturing is essential for sustaining production in tight oil reservoirs due to rapid post-stimulation decline rates, yet optimizing its timing remains challenging. This study develops a two-phase (oil-water) flow model using finite difference methods to simulate fracture-porous media. The governing equations are solved with the IMPES approach to predict flow and production. Validated with Well X data, the model closely matches actual trends (3.1% deviation in reservoir pressure). Comparing initial and repeated fracturing geometries reveals key production mechanisms: high-permeability fractures increase from 14 to 21 (33% density rise), boosting oil output but accelerating pressure depletion and shortening steady flow periods. Early re-fracturing maximizes cumulative output: simulations show re-stimulation at four years extends production by 18% versus delayed interventions. Gradual pressure decline requires proactive planning to avoid productivity loss. Field validation confirms the model’s accuracy, with repeated fracturing boosting oil production by 26% over five years. Results highlight the need to balance fracture-network expansion with pressure maintenance. The proposed two-phase flow model offers a transferable methodology for optimizing re-stimulation schedules based on reservoir dynamics. This work enhances recovery strategies in heterogeneous tight oil systems by linking fracture evolution and flow behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tight oil holds significant potential for exploration and development in the unconventional oil and gas sector. Prominent oil and gas basins such as Junggar and Ordos in China possess abundant reserves of tight oil and gas resources1,2,3,4,5. The “horizontal well + multi-stage hydraulic fracturing” technique has emerged as the primary method for exploiting these reservoirs, significantly enhancing their production capabilities6,7,8,9. However, due to the poor physical properties of tight oil reservoirs, continuous resource extraction leads to a substantial decline in formation energy, rendering horizontal wells ineffective at establishing an efficient injection and production network that can replenish this energy. Consequently, there is a gradual decrease in productivity over time. Additionally, under the closure pressure exerted by the formation, fracturing proppants undergo deformation, embedding, and crushing processes, leading to a rapid deterioration of fracture conductivity. This results in a swift decline in oil well productivity. As reservoirs continue to be developed and exploited further, certain hydraulic fractures within horizontally drilled wells experience reduced conductivity levels, contributing to a rapid drop in oil production rates during the short stable production period. This significantly hampers the effective development outcomes of tight oil reservoirs10,11,12,13. To restore productive capacity to wells experiencing declining output rates, re-fracturing technology stands out as one of the most promising measures widely employed for enhancing production efficiency6,10,14,15,16.

With the extensive development of unconventional oil and gas resources, such as tight oil and gas, re-fracturing technology for horizontal wells has garnered increasing attention17,18,19. Determining the optimal timing for re-fracturing is a critical aspect of researching horizontal well re-fracturing, as it enables achieving the most effective hydrocarbon stimulation. While it is generally believed that the best time to re-fracture vertical wells is when there are significant changes in in-situ stress, leading to improved sweep efficiency and reduced unswept oil areas, determining the ideal timing for re-fracturing horizontal wells involves numerous factors20,21,22,23. Typically, optimization of horizontal well re-fracturing timing is conducted through numerical simulation using cumulative oil and gas production or net present value (NPV) as objective functions. Lantz et al. discovered that the optimal timing for re-fracturing shale reservoirs in the Bakken Basin varies depending on both the initial fracturing completion method and subsequent re-fracturing processes; they found that implementing re-fracturing 2 to 3.5 years after initial fracturing achieves superior stimulation effects for oil wells24. Tavassoli et al. enhanced the computer modeling group (CMG) seepage model and established a numerical model to predict optimal re-fracturing timing by evaluating daily and cumulative gas production of shale gas wells. Their results indicate that peak stimulation effects can be achieved when daily gas production drops to 10–15% of initial production levels25. Cafaro et al. (2016), based on three natural gas price prediction models, utilized net present value (NPV) as an objective function to optimize both the number and timing of re-fractures in shale gas horizontal wells corresponding to each price change26.

Lei et al. presented a comprehensive approach for calculating stress changes and dynamic fracture propagation, integrating discrete-fracture, geomechanics, and multi-well production simulation models. Their simulation results provided valuable insights into the propagation of both new and existing fractures during the re-fracturing process, offering significant potential for improved oil recovery in tight oil reservoirs27. Kong et al. reviewed the fundamentals and historical development of re-fracturing technology, discussing criteria for selecting wells for re-fracturing. They categorized the re-fracturing procedure into four main stages: parameter model definition, statistical analysis, classification methods, and numerical simulation28. Luo et al. investigated re-fracturing simulation of horizontal wells using an integrated process that couples fracturing, production, and four-dimensional in-situ stress simulation. This approach enhances the understanding of fracture behavior under complex conditions29. Xiong et al. developed a multi-level evaluation model to quantify the potential for re-fracturing in each horizontal well. The model considered fourteen factors from geological parameters, engineering parameters, and production performance parameters, providing a systematic assessment framework30.

Li has constructed a mathematical model for the fracture propagation of carbon dioxide fracturing based on the coupled mechanism of seepage-stress-damage, aiming to analyze the influence of different drilling fluid components and reservoir parameters on the fracture propagation behavior in low-permeability reservoirs31. Wang et al. examined the re-fracturing effect in low-permeability reservoirs under a five-spot well pattern, revealing the mechanisms of vertical-horizontal well combinations. They also analyzed the impact of different soak times on reservoir production performance characteristics32. Ren et al. developed a novel integrated workflow for re-fracturing tailored to complex fracture networks. This workflow incorporated the hydraulic fracture propagation during initial fracturing and dynamic stress changes during the initial production phase, enhancing the effectiveness of re-fracturing operations33. Xu et al. systematically evaluated key factors such as stress difference, displacement, and fracturing fluid viscosity on the fracture temporary plugging diversion (TPD) law using a true triaxial hydraulic fracturing simulation device and cohesive element model, providing critical insights into TPD mechanisms34.

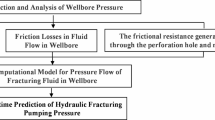

Existing research on the timing decision-making for refracturing in horizontal wells faces the following technical limitations: Firstly, traditional modeling methods are mostly based on the assumption of single-phase flow, making it difficult to accurately characterize the nonlinear coupling effect between oil-water two-phase competitive flow and fracture reconstruction, thus leading to significant prediction errors in stimulation effect. Secondly, the economic evaluation system dominated by net present value (NPV) does not fully consider the cumulative effect of reservoir damage during long-term production, resulting in significant deviations between theoretical optimization schemes and actual field implementation effects.

A two-phase flow model for oil and water in a dual-medium fracture-pore reservoir with artificial fractures is established, accounting for the distinct characteristics of each medium. The governing equations are discretized using the finite difference method, and the Implicit Pressure Explicit Saturation (IMPES) approach is employed to solve the system, enabling predictions of oil and water production. Subsequently, numerical simulations are conducted to analyze multi-fracture profiles generated by staged fracturing in horizontal wells within tight reservoirs, considering both primary fracturing and re-fracturing scenarios. The study further explores the variation patterns of oil production capacity and formation pressure distribution following re-fracturing at various intervals post-initial fracturing. Calculations are performed to evaluate changes in single-well crude oil production after re-fracturing at different time intervals, aiding in the identification of optimal re-fracturing timing for horizontal wells in tight reservoirs and providing a robust theoretical foundation for efficient reservoir development.

Geological characteristics and mechanical analysis of reservoirs

Physical property

A statistical analysis of the thin section electron microscope data from the study area indicates that the sedimentary components of the reservoir are notably complex, with fillers predominantly consisting of quartz, plagioclase, and calcite. The rounding degree of the sedimentary particles is primarily subangular, accompanied by poor sorting characteristics. Particle support is predominantly grain-supported, with contact patterns mainly characterized by line-point and point-line interactions. The cementation types are primarily pressure embedding and porosity-related, with pressure embedding occupying a secondary position.

The results of the porosity and permeability parameter analysis for reservoir rock samples indicate that the range of reservoir thickness is approximately 37 to 46 m, the average matrix porosity is 9.48%, and the water saturation is 27.84%. The arithmetic mean permeability is measured at 1.58 × 10− 3 μm². Based on the characteristics of the capillary pressure curve, it can be inferred that the proportion of matrix pore throats smaller than 0.1 μm is predominant; conversely, the primary permeable pore throat radius exceeds 1 μm, with a lower limit set at 0.4 μm. Analyzing both porosity and permeability parameters alongside capillary pressure testing results reveals that the overall performance of matrix properties within the reservoir is suboptimal, exhibiting minimal storage and permeability capacity. Consequently, enhancing reservoir permeability through hydraulic fracturing becomes essential.

Formation temperature and pressure

The oil reservoir of the study area is classified as a normal pressure and temperature system, with formation pressure of 49.87 MPa. Based on calculations, the geothermal gradient at the formation depth is 3.0 ℃/100 m, while the rock’s compressibility coefficient is measured at 2.9 × 10− 4 MPa− 1.

Reservoir fluid properties

The average density of crude oil within the reservoir is 0.801 g/cm2, with its viscosity at 120 °C averaging 10.97 mPa s. The compressibility coefficient of crude oil is recorded at 8.3 × 10− 4 MPa− 1, whereas that of formation water is 4.5 × 10− 4 MPa− 1. The volumetric coefficients for both crude oil and formation water are measured at 1.1 and 1.0, respectively.

The mineralization range of the formation water is between 100,326 and 220,347 mg/L, with an average concentration of 172,658 mg/L. The chloride ion concentration ranges from 54,247 to 164,932 mg/L, while the sulfate ion concentration varies from 34 to 19,245 mg/L. The pH value spans from 6.0 to 8.6, averaging at 7.5, which indicates that the formation water exhibits weak alkalinity; it primarily consists of CaCl₂ and NaHCO₃ types.

Ground stress analysis

Based on the current rock mechanics parameter results, the maximum average horizontal stress is 97 MPa, while the minimum average stress is 76 MPa. The maximum horizontal stress difference in the surrounding area is 8.08 MPa, with a minimum stress difference of 5.34 MPa and an average stress difference of 8.17 MPa. Given that the coefficient of variation for each well layer is below 2.20, this criterion suggests that the reservoir in this region is conducive to fracture network formation during hydraulic fracturing due to favorable stress conditions.

Through a comprehensive analysis of the lithology, physical properties, temperature, pressure, and fluid characteristics of the composite reservoir, it is determined that the oil reservoir in the study area predominantly exhibits low porosity, low permeability, and conditions of constant temperature and pressure. These data parameters provide the fundamental parameters for subsequent numerical simulations.

Oil-water two-phase flow model in fracture-pore dual media

The mathematical representation of oil-water two-phase flow in fractures is formulated as follows: In the Navier–Stokes equations, the two-phase flow is characterized by gravitational segregation, thereby eliminating the need for interfacial tension to define the oil-water interface. This approach parallels the use of grid-based oil saturation methods for depicting oil-water distribution in traditional reservoir numerical simulations, effectively reducing both model complexity and computational requirements. Importantly, fractures significantly enhance fluid mobility within porous media, markedly altering flow patterns compared to homogeneous formations. By integrating gravitational effects into the Navier-Stokes framework, one can accurately capture how density differences between oil and water influence their movement through fractured rock. Furthermore, employing grid-based methods facilitates a more straightforward implementation of numerical algorithms that simulate fluid dynamics under varying conditions. These grids enable multi-scale calculations and allow researchers to efficiently analyze complex interactions between fluids and solid matrix materials.

The principles governing seepage in a dual-medium fracture-pore system can be summarized into three fundamental concepts: mass conservation (including fluid mass conservation in both the bedrock and artificial fractures, as well as solid mass conservation), Darcy’s law, and the equation of state. When formulating the equation of state for rock mass, it is treated as a unified entity comprising rock particles and pore fluids, thereby enabling a holistic study of the rock mass. Conversely, when establishing the equation of state for pore fluids, reference is made to the seepage mechanics model, assuming that all spaces within the seepage zone are fully saturated with fluid, without any presence of a rock skeleton.

Model assumptions

The reservoir exhibits a rectangular geometry, and fluid flow within it is characterized by isothermal seepage. It represents a two-dimensional plane flow, neglecting the influence of gravity. The reservoir contains only two immiscible phases—oil and water—both of which obey Darcy’s law. Both the rock matrix and the fluids exhibit compressibility. The analysis accounts for the heterogeneity and anisotropy of the rock formation, as well as capillary forces between the oil and water phases. Additionally, a fracture fully penetrates the entire thickness of the reservoir.

Oil-water two-phase flow equation

Reservoir matrix system

Differential equation of oil-water two-phase flow is as follows:

where, \(\:k\) is the Absolute permeability of the formation, mD. \(\:{k}_{ro}\) is the Relative permeability of oil phase, dimensionless. \(\:{k}_{rw}\) is the Relative permeability of water phase, dimensionless. \(\:{\mu\:}_{o}\) is the Oil phase fluid viscosity, mPa·s. \(\:{\mu\:}_{w}\) is the Water phase fluid viscosity, mPa·s. \(\:{s}_{o}\) is the Oil phase fluid saturation. \(\:{s}_{w}\) is the Water phase fluid saturation. \(\:{p}_{o}\) is the Oil phase pressure, MPa. \(\:{p}_{w}\) is the Water phase pressure, MPa. \(\:\phi\:\) is the Formation porosity.

Auxiliary equation:

Initial conditions:

The outer boundary of the model is a closed boundary:

The inner boundary is a constant bottomhole flow pressure.

where, \(\:{p}_{c}\) is the Capillary pressure, MPa. \(\:{p}_{oi}\) is the Original formation pressure, MPa. \(\:{s}_{wi}\) is the The original water saturation of the formation, dimensionless. \(\:{p}_{wf}\) is the Bottom hole flow pressure, MPa. Lx is the Transverse extension length of fracture, m. Ly is the Longitudinal extension length of fracture, m.

Fracture system

The production of tight reservoirs is primarily reliant on fractures. Within the reservoir, there may exist one or multiple fracture groups, with most fractures in each group exhibiting a relatively consistent orientation. The presence of fractures alters the permeability of the rock medium within the reservoir, resulting in two aspects: heterogeneity and discontinuous spatial distribution of permeability. This heterogeneity can be referred to as fracture-pore heterogeneity and represents microscopic or local characteristics. It arises from the fact that fracture permeability is significantly higher than pore permeability in matrix rocks, leading to uneven spatial distribution of permeability within the reservoir. The strength of this heterogeneity depends on two factors. (A) The ratio between single fracture permeability (kf) and matrix pore permeability (km), denoted as kf/ km. (B) The frequency or average distance between fractures in space, represented by d. A stronger heterogeneity occurs when kf/km is larger and d is smaller (indicating higher frequency). Conversely, a weaker heterogeneity exists when kf/km and d fall within certain limits commonly observed during oilfield development.

On the contrary, the presence of fractures induces anisotropy in reservoir permeability. Fractures exhibit high conductivity solely along their parallel direction, while having no impact on flow perpendicular to the fracture orientation. Consequently, within fractures, the permeability of a given point varies significantly depending on direction, resulting in anisotropy. Simultaneously, the pore permeability of rock matrix between two fractures remains unchanged. From a macroscopic perspective, overall reservoir permeability exhibits directional characteristics. Parallel to the fracture orientation has higher permeability compared to perpendicular directions – indicating anisotropy. The degree of anisotropy in fractured reservoirs is determined by the ratio kf/km (permeability of a single fracture divided by pore permeability) and distance between fractures d (or spatial frequency). Greater kf/km values and smaller d values (higher frequency) result in more pronounced anisotropy; conversely, weaker anisotropy occurs with lower kf/km ratios or larger d values (lower frequency). For fluid flow within a fracture system analysis assumes one-dimensional behavior without considering capillary forces present within fractures. Therefore, the oil-water two-phase flow equation for fractured systems can be expressed as follows.

Initial conditions:

The outer boundary of the fracture is a closed boundary:

The inner boundary is a fixed bottom hole flow pressure:

Discretization and solution of equations

In order to ensure flow continuity, pressure balance, and accurate calculations for both systems, a unified grid system is employed to divide the matrix and fracture. For computational convenience, the wellbore can be treated as an extended fracture. Due to the significant difference in scale between the fracture aperture and grid size, uniform division of matrix and fracture grids is carried out along the direction of the fracture (Fig. 1). The governing equations for oil phase and water phase seepage are discretized using central difference scheme, resulting in a five-diagonal matrix equation set. Independent variables \(\:{p}_{o}\) and \(\:{s}_{w}\) are selected, while solving them through implicit pressure explicit saturation (IMPES) method. That is, an implicit iterative approach is used for pressure calculation while “one step pressure, multiple step saturation” method is adopted for saturation calculation. Specific solution steps can be found in Appendix A.

The oil flowing into the well through the fracture system is:

where, \(\:{k}_{f}\) is the Fracture permeability, mD. \(\:{w}_{f}\) is the Fracture aperture, m. \(\:S\) is the Formation skin factor, dimensionless. \(\:{B}_{o}\) is the Volume coefficient of crude oil, dimensionless. \(\:{r}_{e}\:\) is the Radius of grid conversion, m. \(\:{q}_{of}\) is the Flow rate of crude oil in fracture, m3/s.

Model validation

Physical model of initial fracturing

Taking a horizontal open-hole well in a tight oil reservoir as an example, the comprehensive logging interpretation results show that three types of reservoirs are identified within a horizontal section length of 600 m. Among them, the cumulative effective thickness of Type I reservoirs is 175.93 m, with the main lithology being fine conglomerate, exhibiting significantly superior pore structure parameters (1.47) and quality factors (8.04), and possessing high porosity and permeability characteristics (Φ = 12.58%, K = 20.65 mD). Type II reservoirs have a thickness of 189.78 m, mainly distributed in the middle and shallow strata, exhibiting typical medium porosity and medium permeability characteristics (Φ = 11.26%, K = 4.76 mD). Type III reservoirs have a development thickness of 234.29 m, mostly distributed in the top and bottom areas in the form of thin interbeds, with significantly reduced physical property parameters (Φ ≤ 9.64%, K ≤ 1.21 mD). Statistical analysis indicates that the proportion of high-quality reservoirs in this horizontal section reaches 20.8%, with reservoir space types mainly being intergranular dissolved pore-fracture composite types, demonstrating good potential for oil and gas development.

Based on the geological characteristics of the well, a fracturing plan divided into 7 sections was designed. The red straight line indicates the segmentation of the horizontal well, while the blue straight line represents the horizontal wellbore. The model study area is set to be 600 m × 300 m.

Model parameters and results

The reservoir parameters required for predicting the production of Well X following initial fracturing are summarized in Table 1. After conducting the fracturing simulation, a total of 14 effective fractures were generated, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The length, conductivity, and average width of each fracture level were calculated and recorded in Table 2. By incorporating these well parameters into the oil-water two-phase permeability model, it becomes feasible to evaluate variations in reservoir permeability post-fracturing (Fig. 3) and the corresponding changes in crude oil production.

According to the model calculation results, the fitting formulas of relative permeability of water phase and oil phase are calculated respectively:

History matching of oil well production history

The X reservoir has consistently demonstrated production for approximately 2000 days since the initial fracturing operation. By adjusting parameters such as the oil-water relative permeability relationship, the fitted predicted oil production curve exhibits consistent variation patterns with the actual production curve. Figure 4 illustrates the temporal variation in both predicted and actual daily oil production since the initiation of fracturing, while Fig. 5 presents the corresponding cumulative oil production. Comparative analysis confirms that the trend depicted by the fitted predicted oil production curve aligns closely with that of the actual production, thereby validating the reliability of the established two-phase permeability model for oil-water systems.

To validate the accuracy of the established oil-water two-phase flow model, a comparison can be made between the predicted formation pressure and the actual downhole pressure. The formation pressure distributions of Well X after 1 month and 6 years of production following initial fracturing were calculated, with the corresponding predicted results presented in Figs. 6 and 7. According to Fig. 6, after 1 month of production, the formation pressure around the intersection of the wellbore and fracture is approximately 30 MPa. In contrast, one month after initial fracturing, Well X recorded a bottom hole flowing pressure measurement of 29.1 MPa using a downhole pressure gauge (data sourced from Well X’s daily production report), resulting in an error rate of only 3.1% when compared with the model’s predicted results. This indicates that the established oil-water two-phase flow model demonstrates high levels of accuracy.

Subsequently, as crude oil exploitation continues over time, although minimal changes are observed in formation pressures surrounding the wellbore area, low-pressure regions gradually expand towards both sides between fractures along their tip directionality. Eventually, after six years, this expansion forms an elliptical-shaped low-pressure region parallel to the fracture directionality, as shown in Fig. 7. The magnitude within this low-pressure region measures approximately 19 MPa.

Optimization of timing for re-fracturing

Physical model and parameters of re-fracturing

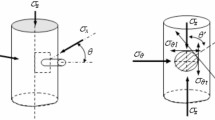

Prior to conducting repeated hydraulic fracturing operations in a vertical fracture well, the induced stress from the initial artificial fracture, combined with the reduction in pore pressure during oil and gas production, resulted in a decline in reservoir stress. This change altered the stress orientation within the wellbore and its surrounding area. If hydraulic fracturing is conducted again at this stage, it is likely that new fractures will form perpendicular to the initial fracture. The stress distribution in the near-well region facilitates the formation of these perpendicular fractures during repeated hydraulic fracturing. However, this effect is limited to a narrow zone adjacent to the wellbore. As these new fractures propagate, the stress distribution within the reservoir continuously changes, directly influencing and governing the direction of fracture extension.

When repeated hydraulic fracturing induces new fractures that extend to a certain distance, the stress direction will revert to its initial state once the redirection caused by induced stress ceases. Consequently, as these new fractures reach a specific distance (i.e., the isotropic stress point), their extension direction may gradually realign parallel to the length of the initial fracture with ongoing hydraulic fracturing operations, as illustrated in Fig. 8. If the stress direction does not undergo further redirection under specific conditions, such as the influence of adjacent wells, during the process of repeatedly fracturing to extend new fractures, these new fractures will continue to propagate forward and may result in longer turning fractures. Figure 9 illustrates the geometric characteristics of new fractures that develop in an oil well following repeated hydraulic fracturing. Assuming the presence of a vertical fracture well, the initial fracture length produced by the first hydraulic fracturing is denoted as \(\:{L}_{xf}\), with its orientation being perpendicular to the direction of the minimum horizontal principal stress. The newly formed fractures resulting from repeated hydraulic fracturing are oriented at an angle 90° relative to the initial fracture length direction. The distance from the wellbore to the isotropic point along the extension of these new fractures is defined as \(\:{L}_{xf}^{{\prime\:}}\), while their vertical penetration depth within the reservoir beyond this isotropic point is designated as \(\:{L}_{xf}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\).

By incorporating the fault values used in the re-fracturing design and the latest updated boundary conditions into the seepage model, it is possible to calculate production changes following initial fracturing and subsequent multiple fracturing operations after a certain period. According to the scheme formulated for multiple fracturing of Well X, in addition to re-processing the 14 initial fracturing locations in the original seven horizontal intervals, seven additional locations within these intervals were selected for supplementary perforation and re-fracturing based on logging interpretation results. The same fracturing parameters as those used in the initial fracturing were applied.

Simulation of initiation of refracturing fractures

Stress redistribution after refracturing

Following the formation of the initial hydraulic fracture, prolonged production activities in the oil and gas well lead to a redistribution of local pore pressure within the elliptical region surrounding the wellbore. Consequently, both the initial hydraulic fracture and variations in pore pressure jointly influence the stress distribution within the reservoir. Numerical simulation results indicate that the horizontal stress component parallel to the hydraulic fracture (the maximum horizontal principal stress) exhibits rapid changes, whereas its perpendicular counterpart (the minimum horizontal stress) varies at a comparatively slower rate; both components are functions of time and space. Therefore, when the induced stress differential in a repeated fracturing well is sufficient to alter the initial stress differential within the formation, a reorientation of stresses occurs in both the wellbore and its surrounding elliptical area: specifically, the original minimum horizontal stress direction may transition into the current maximum horizontal stress direction, while conversely, the original maximum may become the current minimum.

If stress redirection (the reversal of the maximum and minimum principal stress directions) occurs in the wellbore and its vicinity during refracturing of a previously fractured well, newly formed fractures may initiate and propagate perpendicular to the extension direction of the initial fracture until they reach the elliptical boundary of stress redirection (i.e., the isotropic stress point). Beyond this boundary, the stress field reverts to its initial state, at which point these new fractures gradually realign parallel to the extension of the initial fracture. If no further redirection takes place, they will continue propagating along this alignment. However, due to the presence of existing fractures, newly formed repeat fractures are more likely to propagate along the same direction. Consequently, the redirection of these repeat fractures is influenced not only by stress redirection but also closely tied to construction methods; thus, a certain driving force must be applied to facilitate a smoother transition into a new directional alignment.

In the reservoir of a repeat-fractured well, the primary factors that can induce stress changes are: (a) Stress variations resulting from the initial hydraulic support fracture. (b) Stress variations due to pore pressure fluctuations during production in the vertical fracture well.

If the magnitudes of these induced stress changes are known, it becomes possible to calculate the spatial and temporal distribution of the stress field around the repeat-fractured well, as well as predict the initiation and propagation directions of new fractures generated by refracturing.

In order to perform the superposition of elastic stress field, the stresses must be unified to the same coordinate system. For this reason, this study chooses a rectangular coordinate system, so the stress solution obtained in polar coordinates (x, y) needs to be converted to the rectangular coordinate system (r, θ). The conversion formula is as follows:

In the above equation, if the shear stress \(\:{\tau\:}_{xy}=0\), i.e., no induced shear stress is generated, the \(\:{\sigma\:}_{x}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{y}\) obtained at this time are respectively the maximum and minimum horizontal stress in the reservoir, and their respective directions are the directions of the maximum and minimum horizontal stress.

\(\:\varDelta\:{\sigma\:}_{Hf}\), \(\:\varDelta\:{\sigma\:}_{hf}\), \(\:\varDelta\:{\sigma\:}_{xyf}\) are the maximum and minimum horizontal stresses and shear stresses in the direction of the hydraulic fracture, MPa. \(\:\varDelta\:{\sigma\:}_{Hp}\), \(\:\varDelta\:{\sigma\:}_{hp}\), \(\:\varDelta\:{\sigma\:}_{xyp}\) are the maximum and minimum stress directions and shear stress caused by production, MPa. \(\:\varDelta\:{\sigma\:}_{Ha}\), \(\:\varDelta\:{\sigma\:}_{ha}\), \(\:\varDelta\:{\sigma\:}_{xya}\) are the maximum and minimum horizontal stresses and shear stresses in the direction of the fracture and production-induced stresses for adjacent wells, MPa.

\(\:{\sigma\:}_{H}\) indicates the initial maximum horizontal stress direction (parallel to the initial crack direction, i.e. the x-axis direction), MPa. \(\:{\sigma\:}_{h}\) indicates the initial minimum horizontal stress direction (perpendicular to the initial fracture direction, i.e. the y-axis direction), MPa. Therefore, the current stress field is:

-

(1)

The stress changes at the wellbore (\(\:x=0,y=0\)).

The distribution characteristics of the induced stress field at the wellbore determine the direction of initiation of new fractures under high pressure.

-

(2)

Stress changes along the initial fracture direction (Fracture surface, y = 0).

-

(3)

Stress changes along the initial vertical fracture direction (x = 0).

Based on the calculation model, the stress distribution around the wellbore following repeated hydraulic fracturing can be determined, and a preliminary prediction of the optimal timing and distance for subsequent hydraulic fracturing (i.e., the vertical extension distance perpendicular to the initial fracture) can be made.

Mathematical model for initiation and propagation of new fractures

In the repeated fracturing technology, the assumptions based on which the process of fracture initiation and propagation is simulated are as follows.

-

(a)

The rock of the fracturing target layer is regarded as an ideal linear elastic fracture body.

-

(b)

The fracturing fluid is assumed to be a power-law fluid with slightly compressible properties.

-

(c)

The two wings of the crack are symmetrically distributed around the wellbore as the center.

-

(d)

The fracturing fluid flows in a one-dimensional manner along the length of the fracture.

Given the slightly compressible nature of fracturing fluid, its volume change can be neglected during fracturing process. Based on the principle of mass conservation, the volume of injected fracturing fluid can be divided into two parts: one part is used to fill the fractures, while the other part leaks and enters the formation.

At any position x along the length of the fracture, a unit of length \(\:\varDelta\:x\) is taken. Assuming that the volume flow rate of fracturing fluid at this position is \(\:q\left(x,t\right)\) and the volume filtration rate over the unit length is \(\:\lambda\:\left(x,t\right)\), according to the principle of volume balance, the flow rate change rate through a certain vertical section is equal to the sum of the filtration rate of fracturing fluid per unit fracture length and the change rate of vertical section area due to fracture extension. The specific expression is:

Using the Carter filtration model, it is obtained that,

Substituting Eq. (35) into Eq. (34) yields:

where, \(\:A\left(x,t\right)={\int\:}_{-\frac{h\left(x,t\right)}{2}}^{\frac{h\left(x,t\right)}{2}}w\left(x,z,t\right)dx\). \(\:q\left(x,t\right)\) is the volume flow rate of fracturing fluid at location x within the fracture at time t, m3/s. \(\:A\left(x,t\right)\) is the cross-sectional area of the crack at location x within the crack at time t, m2. \(\:h\left(x,t\right)\) is the seam height at position x within the seam at time t, m. t is the time of fracturing operation, s. \(\:w\left(x,z,t\right)\) is the ccrack width at the longitudinal z position on the cross-section at x within the crack at time t, m. \(\:{C}_{t}\) is the comprehensive filtration coefficient of fracturing fluid, \(\:m/\sqrt{min}\). \(\:\tau\:\left(x,t\right)\) is the time required for the fracturing fluid to reach point x at time t, s.

Boundary condition

.

Initial condition

.

The solution is obtained using the finite difference method. Assuming that the first stage of fracturing fluid pumping is completed at time \(\:{t}_{1}\), with a fracture length of \(\:{L}_{1}\) at this point. The fracture is divided into \(\:{N}_{1}\) segments, each with a length of \(\:\varDelta\:x\), and the differential equation in Eq. (36) is discretized using finite difference methods. Subsequently, the transformed Eq. (36) is solved simultaneously with Eqs. (37) and (38) to obtain the values of various parameters within the fracture. Finally, based on the principle of volume balance, further solutions are obtained for related variables. For the solution process of fracturing fluid in other stages, the method is consistent with that of the first stage. Ultimately, with the obtained parameters, the fracture length and width at any position within the fracture can be further calculated.

Simulation results

Simulation of initiation of rep-fracturing fractures

Combined with the fracturing model and stress redistribution analysis, this study quantifies new fracture characteristics (half-length, conductivity, width) around horizontal wells post-refracturing. Comparing these parameters with initial fracturing data reveals the enhanced fracture network effectiveness.

Refracturing resulted in the formation of nine new fractures at seven locations following supplementary perforation, including two extended fractures formed by extending shorter initial fractures. Figure 9 illustrates the simulation results of the initiation and propagation of these refracturing fractures, where the blue box represents new fractures. According to the fracture parameters simulated by the fracturing software (Table 3), the average conductivity of old fractures after refracturing is 68.04 D·cm with an average fracture aperture of 4.78 mm, while that for new fractures is 62.76 D·cm with an average fracture aperture of 4.96 mm and an average length of approximately 39.8 m. Simulation results demonstrate that newly formed fractures through refracturing completely transform previously unaffected areas from initial fracturing, achieve balanced transformation in heterogeneous reservoirs within the horizontal section, and enhance oil well productivity.

Daily oil production forecast

The simulation demonstrates the impact of refracturing on Well X’s oil production changes at 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 years after the initial fracturing. The calculation time is set to 10 years post-initial fracturing. Figure 10 illustrates the predicted curve of daily oil production changes following refracturing at different intervals from the initial fracturing of Well X. The predictions indicate that regardless of when refracturing is implemented, there will be a rapid increase in daily oil production capacity for the well. The maximum daily oil production after refracturing can reach up to 45 t/d. However, it subsequently declines rapidly. Generally, oil production stabilizes gradually within a period ranging from 0.5 to 2 years after implementing refracturing. Furthermore, stable daily oil production post-refracturing surpasses that without its implementation. Simulation results reveal that earlier implementation of refracturing leads to an extended stable production period, emphasizing the significance of maintaining sufficient formation energy for consistent daily oil output levels. As well development progresses, formation pressure gradually decreases, consequently shortening the duration of stable production during later stages of refracturing.

Accumulated oil production forecast

The cumulative oil production curve of well X, following the initial fracturing, is illustrated in Fig. 11 for various time intervals after the implementation of refracturing. It can be observed that the most optimal outcomes in terms of maximum cumulative oil production are achieved when refracturing is conducted 4 years after the initial fracturing. Therefore, it is recommended to implement refracturing at the 4-year mark.

The cumulative oil production over a ten-year period following the initial fracturing is depicted in Fig. 12. It is evident that conducting refracturing after the fourth year yields higher cumulative oil production. Based on predictions derived from the cumulative oil production data, it can be inferred that implementing refracturing four years after the initial fracturing results in maximum productivity. Conducting refracturing earlier enhances overall well performance.

Conclusions

-

(1)

A two-phase oil-water seepage model is developed for a dual-medium fracture-pore system, employing a unified grid to discretize the matrix and fractures. The governing equations are discretized using the finite difference method, and the oil well production is predicted using the implicit pressure and explicit saturation (IMPES) method. Numerical simulations cover the generation of multi-fracture profiles through primary fracturing of horizontal wells in tight reservoirs, as well as simulating new fractures formed by re-fracturing based on these profiles. Re-fracturing technology generates an additional seven fractures beyond those created during primary fracturing, achieving multi-fracture initiation and uniform reconstruction of heterogeneous reservoirs.

-

(2)

Through fitting the two-phase oil-water seepage model, we obtain an oil well production prediction curve that closely aligns with actual production data. Simulations and predictions are conducted for the formation pressure distribution maps of Well X at 1 month and 6 years post-primary fracturing. After 1 month, the formation pressure at the intersection between the horizontal section and fractured zone is approximately 30.0 MPa, which decreases to around 19.1 MPa after 6 years. Additionally, measurements from the downhole pressure gauge indicate that the bottom hole flowing pressure of Well X after 1 month closely matches our model’s predicted result (30.0 MPa), with an error rate of only 3.1%. This validates the accuracy of our two-phase oil-water seepage model in predicting oil production.

-

(3)

Following the primary fracturing, the daily and cumulative oil production of Well X were simulated for 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 years to assess the impact of re-fracturing. The simulation results reveal that re-fracturing can significantly enhance daily oil production by up to 60%, with a gradual stabilization observed within 0.5 to 2 years post-re-fracturing. The decline in formation pressure accelerates this stabilization process, indicating that earlier implementation of re-fracturing leads to an extended stable production period. Calculation results suggest that the optimal timing for re-fracturing is four years after the initial fracturing.

-

(4)

While the current validation relies solely on Well X data, the oil-water two-phase flow model demonstrates inherent adaptability across geological settings. To strengthen operational reliability, future work will calibrate the model against multiple wells in varied reservoir formations. This planned expansion of verification scope will transform the methodology from region-specific optimization into a universal toolkit for tight reservoir re-fracturing design, while maintaining its current effectiveness in guiding parameter adjustments for heterogeneous reservoirs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hu, S. Y. et al. Profitable exploration and development of continental tight oil in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 45 (4), 230–242 (2018).

Rui, Z. et al. A quantitative framework for evaluating unconventional well development. J. Earth Sci. 166, 900–905 (2018).

Chen, Q. L. et al. Types, distribution and play targets of lower cretaceous tight oil in Jiuquan basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 45 (2), 227–238 (2018).

Zheng, M. et al. Potential of oil and natural gas resources of main hydrocarbon- bearing basins and key exploration fields in China. Earth Sci. 44, 833–847 (2019).

Feng, Q., Xu, S., Xing, X., Zhang, W. & Wang, S. Advances and challenges in shale oil development: A critical review. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 4, 406–418 (2020).

Guo, J. C., Tao, L. & Zeng, F. H. Optimization of refracturing timing for horizontal wells in tight oil reservoirs: A case study of cretaceous Qingshankou formation, Songliao basin, NE China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 46 (1), 153–162 (2019).

Li, S. et al. Accurate sectional and differential acidizing technique to highly deviated and horizontal wells for low permeable Sinian Dengying formation in Sichuan basin of China. SN Appl. Sci. 4 (5), 152 (2022).

Ghassemi, A. & Kumar, D. On poroelastic mechanisms in hydraulic fracturing from FDI to fracture swarms. In Paper URTEC-3725955-MS, presented at the SPE/AAPG/SEG Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, Houston, Texas, USA (2022).

Li, S. et al. True triaxial physics simulations and process tests of hydraulic fracturing in the Da’anzhai section of the Sichuan Basin tight oil reservoir. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2023.1267782 (2023).

Jacobs, T. Renewing mature shale wells through refracturing. J. Petrol. Technol. 66 (4), 52–60 (2014).

Hui Xiao, Z. et al. Experimental study on proppant diversion transportation and multi-size proppant distribution in complex fracture networks. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 196, 107800 (2021).

Li, J., Liu, P., Kuang, S. & Yu, A. Visual lab tests: proppant transportation in a 3D printed vertical hydraulic fracture with two-sided rough surfaces. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 196, 0920–4105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2020.107738 (2021).

Guo, T. K. et al. Numerical simulation on proppant migration and placement within the rough and complex fractures. Pet. Sci. 19(5), 2268–2283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petsci.2022.04.010 (2022).

Diakhate, M., Gazawi, A., Barree, R. D., Cossio, M. & Barzola, G. Refracturing on horizontal wells in the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas-one operator’s perspective. In Presented at the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 3–5 February (2015).

Lu, M., Su, Y., Zhan, S. & Almrabat, A. Modeling for reorientation and potential of enhanced oil recovery in refracturing. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 4, 20–28 (2020).

Zhang, X., Ren, J., Feng, Q., Wang, X. & Wang, W. Prediction of refracturing timing of horizontal wells in tight oil reservoirs based on an integrated learning algorithm. Energies 14, 20: 6524. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14206524 (2021).

Sidike, A. et al. Huang Bo and Li Xiaogang. Study on the optimization of timing for horizontal well re-fracturing in tight oil reservoir—a case study of baikouquan formation in north mahu oilfield, junggar basin, western china. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering.

French, S., Rodgerson, J. & Feik, C. Re-fracturing horizontal shale wells: case history of a Woodford shale pilot project. In Paper prepared for presentation at the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference held in Woodlands, Texas, U.S.A., 4–6 February (2014).

Li, Q. et al. Wellhead stability during development process of hydrate reservoir in the Northern South China sea: evolution and mechanism. Processes. 13 (1), 40 (2024).

Suppachoknirun, T. & Tutuncu, A. N. Hydraulic fracturing and production optimization in eagle Ford shale using coupled geomechanics and fluid flow model. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 50, 3361–3378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-017-1357-1 (2017).

Hofmann, H., Zimmermann, G., Zang, A. & Min, K. B. Cyclic soft stimulation (CSS): a new fluid injection protocol and Trafc light system to mitigate seismic risks of hydraulic stimulation treatments. Geotherm. Energy. 6, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40517-018-0114-3 (2018).

Li, X., Wang, J. & Elsworth, D. Stress redistribution and fracture propagation during restimulation of gas shale reservoirs. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 154, 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2017.04.027 (2017).

Lin, H., Tian, Y., Sun, Z. & Zhou, F. Fracture interference and refracturing of horizontal wells. Processes. 10, 899. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10050899 (2022).

Lantz, T. et al. Refracture treatments proving successful in horizontal Bakken wells; Richland Co, MT. In Paper prepared for presentation at the Rocky Mountain Oil & Gas Technology Symposium held in Denver, Colorado, U.S.A., 16–18 (2007).

Tavassoli, S. et al. November. Selection of candidate horizontal wells and determination of the optimal time of refracturing in Barnett Shale. In Paper prepared for presentation at the SPE Unconventional Resources Conference Canada held in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, 5–7 (2013).

Cafaro, D., Drouven, M. & Grossmann, I. Optimization models for planning shale gas well refracture treatments. AIChE J. 62 (12), 4297–4307 (2016).

Lei, Z., Wu, S., Zhu, A. X., Zhu, S. & Liu, H. A comprehensive approach for the performance of the re-fracturing horizontal well in tight oil: coupling fluid flow, geomechanics and fracture propagation. In Paper presented at the SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition, Brisbane, Australia. https://doi.org/10.2118/192134-MS (2018).

Kong, L. et al. Refracturing: well selection, treatment design, and lessons learned—a review. Arab. J. Geosci. 12, 117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-019-4281-8 (2019).

Luo, S., Zhao, Y., Zhang, R. & Deng, Z. In-situ stress evolution and refracturing simulations of horizontal wells in tight conglomerate reservoir. In Proceedings of the International Field Exploration and Development Conference 2021. IFEDC 2021. Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering (eds Lin, J.) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2149-0_96 (Springer, 2022).

Xiong, Q. et al. Re-fracturing wells selection by fuzzy comprehensive evaluation based on analytic hierarchy process—Taking Mahu oilfield as an example. Front. Energy Res. 10, 851582. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2022.851582 (2022).

Li, Q. et al. The crack propagation behavior of CO2 fracturing fluid in unconventional low permeability reservoirs: factor analysis and mechanism revelation. Processes. 13 (1), 159 (2025).

Anlun Wang, Y., Chen, J., Wei, J. & Li, X. Experimental study on the mechanism of five-point pattern refracturing for vertical & horizontal wells in low permeability and tight oil reservoirs. Energy. 272, 127027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127027 (2023).

Ren, J., et al. Optimizing refracturing models in tight oil reservoirs: an integrated workflow of geology and engineering based on four-dimensional dynamic stress field. In Paper presented at the International Geomechanics Symposium, Al Khobar. https://doi.org/10.56952/IGS-2023-0114 (2023).

Xu, H., Jiang, H., Wang, J., Wang, T. & Zhang, L. Simulation of fracture propagation law in fractured shale gas reservoirs under temporary plugging and diversion fracturing. Phys. Fluids. 35 (6), 063309. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0151148 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z. and R.D.: writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing, conceptualization. L.C.: project administration, resources. S.L.: visualization, methodology, investigation. C.W.: formal analysis, data curation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Q., Dai, R., Chen, L. et al. Optimization of refracturing timing in tight oil reservoirs based on an oil water two phase flow model. Sci Rep 15, 22907 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06341-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06341-x