Abstract

Microbial biofilms are known to defend against the host’s immune system and provide resistant to antimicrobial medications. Biofilms can form on various human organ systems spanning the gastrointestinal, respiratory, cardiovascular, and urinary organ systems. Conditions caused by the yeast Candida albicans can range from irritating thrush, to systemic and life-threatening candidiasis. Initial contact between organism and surface is mediated electrically, with subsequent interactions developed biochemically. Since different cells have different electrical characteristics, we hypothesised that alteration in these properties may align with different strains’ propensity for biofilm formation. We used three strains of C. albicans with different tendencies for biofilm formation and filament phenotype (the most filamentous strain nrg1 Δ/Δ, the least filamentous ume6 Δ/Δ, and wildtype DK318), we investigated the passive electrical properties, membrane potential Vm and ζ-potential at two conductivities. Results suggest Vm and ζ-potential correlate with a cell’s ability to form biofilms, suggesting correlation between membrane potential, ζ-potential and biofilm formation. Understanding this relationship may suggest potential routes to future prevention of biofouling and biofilm-related illness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A biofilm is a cellular community of microorganisms which adheres to a surface1. These organisms can interact with each other and the surface, in order to grow and subsequently form new colonies. Whilst biofilms are ubiquitous worldwide and represent perhaps the first evolutionary form of multicellular structure that may have led to the first organisms, they also present a hazard to humans; biofilms can form both on surfaces carrying materials for human use, particularly where water is present (such as water pipes and air conditioning systems). Biofilms can also form within the gut and on the surfaces of teeth. Since these may present a hazard to health (particularly in biofilms of pathogenic bacteria), much research has been devoted to developing materials which resist adhesion from organisms with the tendency to form biofilms for use as medical devices specifically such as cannulas or joint replacement devices2.

The main human fungal pathogen, Candida albicans, is the fourth most common cause of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections and the primary cause of oral candidiasis globally3. Those with impaired immune systems, such as cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and recipients of organ transplants, are also more vulnerable to infection. Treatment for candida infections has become more challenging due to the emergence of drug-resistant strains and limited antifungal medications. C. albicans possesses multiple virulence properties that allow it to cause disease.

C. albicans is a successful commensal and part of the human gut microbiota and is most often non-pathogenic. However, C. albicans can lead to a variety of infections due to its ability to colonise surfaces. Candidiasis leads to diseases spanning from local irritation of the skin and oral mucosa (thrush) to systemic candidiasis which can be life-threatening3,4. The pathogenic potential of C. albicans is related to its adhesion, immune evasion, and invasion potential, which is further linked to the formation of biofilms. Biofilm formation involves adhesion to a substrate, cell proliferation and filamentation, and finally, the dispersion of cells, which may lead to further biofilm formation5.

Several strains of C. albicans are known and many have been developed in the laboratory to investigate biofilm formation. C. albicans dimorphism from single oval-shaped cells (yeast) into elongated cells attached end-to-end (pseudohyphal and hyphal filaments) are directly associated with virulence and a variety of virulence-related properties, including tissue invasion, lysis of macrophages and neutrophils and breaching of endothelial cells6. The wild type (WT) DK318 is a commonly used laboratory strain with filament formation phenotype. The Unscheduled Meiotic Gene Expression-6 (UME6) is a major transcription factor that is important for C albicans’ ability to filament7. The UME6 mutant strain under temperature and serum induction leads to a filamentation defect and thereby weakened virulence, which can be used as a model to investigate virulence and cell membrane physiology characteristics with respect to biofilm formation. Negative Regulator of Glucose-represses genes (NRG1) is a DNA-binding protein that represses filamentous growth of C. albicans. The NRG1 mutant strain has a robust filamentation phenotype that leads to increased biofilm formation8,9,10,11.

The formation of biofilms ultimately depends on the cell’s ability to adhere to the surface, which is mediated by multiple mechanisms. One of these is electrostatic; just as the ζ-potential of colloids mediates dispersion or flocculation12, so the ζ-potentials of cells and surfaces play a role in the initial contact and subsequent adhesion of cells in biofilm formation. However, whilst the role of surface ζ-potential is well-characterised in the race to manufacture materials which resist biofilm formation [e.g.13], the role of the cellular ζ-potential has been considered far less frequently. It is more commonly studied in bacteria than fungi, where analyses of the ζ-potential have focussed more on the role of surface chemistry in differentiating between species, and how surface modification can be used to prevent biofilm formation14.

However, beyond surface chemistry, there are other mechanisms by which cells can control their electrostatic interactions with their environment. The concept of cells as bioelectric machines dates back to the late 1700s15, and later formed the basis of our understanding of muscle and nerve, although this was only understood mathematically in the 1940s by Goldman’s seminal paper16 applying the equations of Nernst to the potentials generated by the diffusion of multiple ions against a concentration gradient, in an equation canonically described by Hodgkin and Katz’ paper17. Since then, the resting membrane potential (RMP) of a wide range of animal cells has been measured using the Patch Clamp method18, in which saline-filled micropipettes are used to puncture the membrane to record from the interior. However, this technique is far less amenable to the use where cell walls are present, meaning estimations of the RMP of fungi require indirect measurement, typically using fluorescent dyes.

However, there are other correlates of cell electrical state. For example, the passive electrical properties of cells, such as the resistance and capacitance of the compartments of the cell can be determined through impedance measurement or dielectrophoresis (DEP), the induced movement of suspensoids (including cells) in non-uniform AC electric fields. Unlike its close relative electrophoresis, the frequency-based component of DEP allows determination of the conductivity and permittivity of membrane and cytoplasm by comparing the behaviour at different frequencies with a mathematical model of dielectric behaviour. Recent work19 has also shown that determination of the change in the cytoplasm conductivity δσcyto for a given change in medium conductivity δσmed can be used to determine cell RMP of mammalian cells using the Eq.

Where R, T and F have their standard thermodynamic meanings.

The ζ-potential is commonly defined as the electrical potential at the hydrodynamic plane of shear due to the effect of the cell’s surface charge. Whilst this definition is accurate for inanimate suspensoids, it has been repeatedly shown over the last 50 years20,21,22,23 that for cells, a proportion of the RMP appears as a component of the ζ-potential. This was codified by a study by Hughes et al.24, thus:

Where ζ is the measured ζ-potential, ζ’ is the ζ-potential due only to the surface charge, and Ξ is a proportion of the membrane potential.

Equation (2) suggests that cells may mechanistically change ζ-potential by altering the ionic balance across the cell membrane. Effectively, cells act as miniature electrodes generating an additional extracellular potential and hence modifying ζ-potential. This is important, as ζ-potential is widely used in colloid science as a measure of how well-suspended particles (commonly, but not exclusively, nanoparticles12 repel each other or aggregate due to van der Waals forces at short range. In a review of cellular ζ-potential, Hughes25 recently outlined a correlation between ζ-potential and bacterial behaviour, with lower (more depolarised) values of bacterial ζ-potential being associated with filamentous behaviour, and higher (more polarised) values being associated with monodispersion. The electrophysiology of biofilm formation has been studied, but almost exclusively by considering the ζ-potential of the material on which the biofilm forms, whilst the ζ-potential of the cells themselves have largely remained unobserved.

In this paper, we present the first study on the effects of alterations in the dielectric phenotype of C. albicans variants to ascertain whether parameters such as ζ-potential may play a role in determining the propensity for biofilm formation by comparing two common mutations of the ume6 ∆/∆ and nrg1 ∆/∆ strains. Results suggest a correlation between membrane potential, ζ-potential and filament formation, with differences in RMP (and in particular, ionic composition) suggesting a potential basis for the phenomenon in the complex bioelectricity of the cell.

Materials and methods

Cell preparation

Strains and culture conditions

The study was conducted using wild-type C. albicans (DK318), nrg1∆/∆ (MMC3), and ume6∆/∆ (DK312) strains were kindly provided by Dr David Kadosh (UT Health San Antonio). Cells were grown under minimal filament-inducing conditions, YEPD medium at 30 °C, and under filament-inducing conditions, YEPD medium + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C . Briefly, the indicated strains grew overnight in YEPD medium at 30 °C and cultivated at an OD600 of 4.0. The cultures were diluted 1:10 into 50 milliliters of prewarmed YEPD medium containing 10% (FBS) at 37 °C. The resultant cultures were agitated for 24 h at 200 rpm, as previously described26. The cultures were then fixed with 4.5% formaldehyde in preparation for imaging.

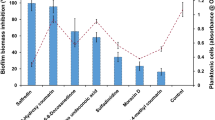

Biofilm formation

The study measured the levels of biofilm growth using a standard, semi-quantitative colorimetric 2 H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT) reduction assay8,27. A 1 × 107 cells/ml wild-type and mutant C. albicans strains cell suspensions were used. The strains were grown 24 h. at 30 °C in non-filamentous YEPD medium and under high filament-inducing conditions (YEPD medium + 10% FBS at 37 °C). The XTT reduction assay is commonly used to measure the viability and proliferation of biofilm cells. Experiments were repeated four times.

Cell characterisation

Cell populations were counted and their radii estimated using a Countess 3 automated cell counter (Thermo Fisher, USA). Prior to analysis, cells were centrifuged at 2000 RCF for 5 min and resuspended in a medium comprising 248 mM sucrose, 16.7 mM dextrose, 250 µM MgCl2 and 100 µM CaCl2, adjusted in conductivity through the addition of Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) to final measured conductivities of 43 mSm− 1 and 150 mSm− 1. All experiments were repeated at least 5 times.

DEP analysis was performed using a 3DEP cytometer (DEPtech, Uckfield UK)28. Samples were resuspended in solutions outlined above at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml, with approximately 85 µl being analyzed by the 3DEP. The 3DEP was used to analyse cells at 20 frequencies equally logarithmically spaced between 10 kHz and 45 MHz at 10 V peak-to-peak for 30 s. A total of five technical repeats were performed. Spectra were analysed using the Clausius-Mossotti autofitting model developed by Tsai et al.25. The passive electrophysiological parameters of specific membrane capacitance Ceff, specific membrane conductance Geff, cytoplasm permittivity εcyto and cytoplasm conductivity σCyto were extracted. Vm was estimated using the σCyto gradient as a function of medium conductivity outlined previously29. A single-shell model was selected rather than a double—shell model, despite the presence of a cell wall, in order to minimise the number of unknowns to enable a unique solution set. Consequently, the membrane values here reflect a combination of membrane and cell wall properties, with significance for determination of differences rather than having absolute physical bearing on the membrane properties.

Cell ζ-potential was measured using the same samples in a Malvern Panalytical Zetasizer Lab Series Blue (Malvern, UK). Simultaneous measurement of medium conductivity was performed during measurement to confirm conductivity values.

Data were compared for statistical significance using two-way Anova with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Correlations were determined using simple linear regression and comparing the significance of the gradient to zero. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, Boston, USA).

Results

The three strains have different propensity for biofilm formation

C. albicans WT and mutant strains biofilms were grown under strong filament-inducing conditions (YEPD + 10% FBS at 37 °C) for 24 h. Scanning electron microscope images revealed a robust filamentous phenotype for the nrg1 ∆/∆ mutant strain in comparison to the predominantly yeast phenotype for the ume6 ∆/∆ mutant strain, as shown in Fig. 1. Next, the biofilm cell viability and proliferation of the indicated strains were quantified by a standard colorimetric XTT reduction assay, with nrg1 ∆/∆ mutant strain demonstrating the highest cellular bioavailability compared to the other two tested strains as shown in Fig. 2.

Wild-type and mutant C. albicans strains were grown under strong filament-inducing conditions (YEPD + 10% FBS at 37 °C) for 24 h. Cells were harvested and fixed using 4.5% formaldehyde and washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline. Images were taken using a scanning electron microscope at 6.00 kx magnification and 20.0 kV acceleration voltage.

ζ-potential correlates with biofilm propensity

The DEP and ζ-potential data are presented in Fig. 3. When we measured the ζ-potential of the cells, we found the results shown in Fig. 3f. As can be seen, the more aggressive nrg1 ∆/∆ strain exhibited the least polarised ζ-potential at -14.8 ± 0.6 mV at low conductivity and − 16.9 ± 0.4 mV at high conductivity. The ume6 ∆/∆ strain was more polarised at -16.8 ± 0.1 mV and − 19.7 mV at low and high conductivity respectively, whilst the wild type was higher still at -18.2 ± 2.8 mV and − 19.8 ± 1.4 mV respectively. Analysis suggests that the nrg1 ∆/∆ strain was significantly different to both ume6 ∆/∆ (P = 0.0009) and wildtype (P = 0.0006) at higher conductivity, and to wildtype (0.007) at lower conductivity. There was no identifiable difference between ume6 ∆/∆ and WT strains at either conductivity (p = 0.32 at low conductivity, 0.98 at high conductivity). Intriguingly, the ζ-potential of all three samples was hyperpolarised at 145 mS/m compared to 43 mS/m, in opposition to expectations from the theory of the effect of charged surfaces on aqueous media, where increased medium ion content reduces the thickness of the electrical double later and correspondingly lowers the ζ-potential.

The derived electrical properties from DEP and ζ-potential analysis (mean ± SEM). Top row: cytoplasm properties of permittivity (a) and conductivity (b). Middle row: membrane properties of specific membrane capacitance (c) and conductance (d) Bottom row: resting membrane potential Vm as determined from Eq. (1) (e) and ζ-potential (f). For clarity, significant difference is only indicated between different strains at the same conductivity, or the same strain at different conductivities.

DEP parameters and estimated RMP

Comparison of the DEP-derived electrical properties did not show statistical significance either between strains or between conductivities for membrane capacitance Ceff, conductance Geff or cytoplasm permittivity εcyto (Fig. 3a-d). Whilst εcyto appeared to exhibit no change (in line with expectations, assuming the relative concentrations of water and protein remains largely similar at both conductivities) both Geff (for all strains) and Ceff (for all strains except ume6 ∆/∆) did exhibit increases in value at the higher conductivity than at the lower conductivity in line with observations of red blood cells, which were attributed to changes in electrical double layer thickness and conductivity19. However, the inter-sample variation (observed in the SEM bars of Fig. 3a-d) meant that no statistically significant differences were observed, either between strains at the same conductivity, or between conductivities for the same strain.

When comparing the derived cytoplasm conductivity values σcyto, no significance was observed between strains when compared at the same medium conductivity, significance was observed between ume6 ∆/∆ and WT when compared between conductivities. Consequently, we observed statistically significant gradients in δσcyto/δσmed. The gradient of wild type, nrg1 ∆/∆ and ume6 ∆/∆ were found to be 0.98 ± 0.32, 0.35 ± 0.25, and 1.275 ± 0.32 respectively (Fig. 3e).

Discussion

Since the problem of biofilm formation is one of cell adhesion to surfaces, and since adhesion is electrostatically mediated through the ζ-potential, it is logical that this parameter plays a role in biofilm formation. However, whilst the effect of the ζ-potential of the surfaces has been studied as a way of developing biofilm-resistant materials, the ζ-potential of the cells forming the film is rarely studied. Previous work with red blood cells24 and platelets30 has demonstrated linear relationships between Vm and ζ-potential in the same medium, suggesting that the cellular processes which control Vm may mechanistically alter the way in which cells interact with their neighbours and environment; for example, Vm depolarisation has previously been linked to cancer cell metastasis31. Furthermore, the role of ζ-potential has been explored in some detail, with bacteria with less polarised ζ-potentials shown to tend towards filament formation, those with more polarised ζ-potential tending to be monodisperse, whilst those in the middle tend to form small clusters. The relationship between Vm and ζ-potential was first reported in the 1970s, and later analysed to suggest that its origin lies in the capacitive potential division of Vm between the cell membrane (and cell wall in the present case) and the intracellular and extracellular electrical double layers.

Using Eq. (1)19 and the slopes described above, we estimate that wild type, ume6 ∆/∆ and nrg1 ∆/∆ cells have RMP values of -12.6 mV, -18.1 mV and − 38.5 mV respectively, shown in Fig. 4a.

(a) Conductivity gradients used to calculate Vm for wildtype (black line), ume6 ∆/∆ (grey line) and nrg1 ∆/∆ (dashed line). (b) Plot of the estimated Vm (± SEM) against the measured ζ-potential; and plots of the propensity for biofilm formation reported using the XTT assay against ζ-potential (c) and Vm (d), together with best-fit lines.

We plotted the ζ-potential, DEP-derived values of Vm, and the absorbance parameter from Fig. 2 as a marker for ability to form biofilms against each other in a pairwise manner which were then fitted with best-fit lines to obtain the three graphs shown in Fig. 4. Considering the relationship between ζ-potential and Vm (Fig. 4b), the best-fit line to the data yields a statistically significant fit (p = 0.023). The slope of the graph suggests that the proportion of RMP appearing in the ζ-potential (the parameter Ξ) has a value of -0.35, and the ζ-potential due to the surface charge, ζ’, has a value − 23.3 mV. Whilst the absolute value of 35% is in close agreement with previous measurements for red blood cells24, platelets30 and cardiomyoblasts32, the negative sign is intriguing, as it is impossible to construct a capacitive division of membrane potential that yields a negative divisor. Instead, this suggests that at the conductivities examined, Vm is actually positive rather than (as assumed in the model) negative. Positive values of Vm (where the cytoplasm is at a higher electrical potential than the medium) are unusual, particularly in mammalian cells, where elevated K+ and depleted Cl− makes the cell interior electrically negative compared to the surrounding medium. However, at the medium conductivities used here, positive Vm of around + 20mV has been observed in red blood cells24 suggesting an alteration of polarity may be appropriate in some instances, particularly if confirmed by ζ-potential. Less is known about cells such as bacteria and fungi, since these typically live in low-conductivity media where they cannot be measured by standard electrophysiology tools such as patch clamp. This makes measurement of Vm reliant on membrane potential sensitive fluorophores; whilst these are useful for indicating the degree of polarizability, they cannot indicate polarity.

When we examined the ability to form biofilms against ζ and Vm, we found further statistically significant relationships, with p-values of 0.0036 and 0.001 respectively (Fig. 4c, d respectively). These results suggest that Vm-mediated ζ-potential offers an opportunity for cells to mechanistically alter their extracellular adhesion characteristics by altering ion content, rather than by surface modification, with biofilm formation correlating well with both hyperpolarisation of Vm and hypopolarisation of ζ-potential.

The enhancement in nrg1 ∆/∆ cells appears to be conferred by chloride becoming the dominant ion in forming the membrane potential; this both reduces the cytosolic ion concentration (and osmotic pressure) whilst polarising Vm. This suggests that among potential approaches to reduction of biofilm formation, an additional treatment might be Cl− channel blockers (e.g33. targeting the ClC1 channel exhibited in C. albicans34 and other yeasts35) – though such interventions may need to be applied before adhesion occurs initially. Whilst these channels have not been explored, recent work on H+ and Ca2+ pump inhibitors influencing biofilm formation36 suggests that alteration of the ion content of the cell does affect biofilm formation. Also of note is that the values of slope for nrg1 ∆/∆ and ume6 ∆/∆ are below and above 1, respectively. Analysis by Hughes et al.19 has suggested that this may be because RMPs are primarily set by anions and cations, respectively, since these mirror the forms of the Nernst equation for those two groups of ions.

This represents an additional case where a mechanistic change in ζ by alteration of Vm may influence cellular interaction with the extracellular environment; previous work has shown links to change in Vm or ζ-potential to rouleaux formation24 and malarial infectivity37 in RBCs, and platelet aggregability30. A better understanding of the manner in which cells behave as electrodes, altering their intracellular interactions with their environment, can lead to improved understanding of methods to intervene and alter those interactions, for clinical and societal benefit.

Data availability

All data are presented in the paper. Raw data files can be obtained from the corresponding author (Michael Pycraft Hughes) on reasonable request.

References

Flemming, H-C. et al. Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 563–575 (2016).

Bryers, J. D. Medical biofilms. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 100, 1–18 (2008).

Pfaller, M. A. & Diekema, D. J. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20, 133–163 (2007).

isid.org/guide/pathogens/fungal-infections.

Talapko, J. et al. Candida albicans-the virulence factors and clinical manifestations of infection. J. Fungi. 7, 79 (2021).

Seman, B. G. et al. Yeast and filaments have specialized, independent activities in a zebrafish model of Candida albicans infection. Infect. Immun. 86, e00415–e00418 (2018).

Braun, B. R., Kadosh, D. & Johnson, A. D. NRG1, a repressor of filamentous growth in C.albicans, is down-regulated during filament induction. EMBO J. 20, 4753–4761 (2001).

Uppuluri, P. et al. Dispersion as an important step in the Candida albicans biofilm developmental cycle. PLoS Pathog. 26, 1000828 (2010).

Cleary, I. A. et al. Examination of the pathogenic potential of Candida albicans filamentous cells in an animal model of haematogenously disseminated candidiasis. FEMS Yeast Res. 16, fow011 (2016).

Carlisle, P. L. et al. Expression levels of a filament-specific transcriptional regulator are sufficient to determine Candida albicans morphology and virulence. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 599–604 (2009).

Wakade, R. S., Wellington, M. & Krysan, D. J. Temporal dynamics of Candida albicans morphogenesis and gene expression reveals distinctions between in vitro and in vivo filamentation. mSphere 9, e00110-24 (2024). (2024).

Lyklema, J. Fundamentals of Interface and Colloid Science (Academic, 1991).

Smith, D. E., Dhinojwala, A. & Moore, F. B. G. Effect of substrate and bacterial zeta potential on adhesion of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Langmuir 35, 7035–7042 (2019).

Ferreyra Maillard, A. P. V., Espeche, J. C., Maturana, P., Cutro, A. C. & Hollmann, A. Zeta potential beyond materials science: applications to bacterial systems and to the development of novel antimicrobials. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1863, 183597 (2021).

Galvani, L. De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari Commentaries (Ex Typographia Instituti Scientiarum Bologna, 1792).

Goldman, D. E. Potential, impedance, and rectification in membranes. J. Gen. Physiol. 27, 37–60 (1943).

Hodgkin, A. L. & Katz, B. The effect of sodium ions on the electrical activity of the giant axon of the squid. J. Physiol. 108, 37–77 (1949).

Neher, E. & Sakmann, B. Single-channel currents recorded from membrane of denervated frog muscle fibres. Nature 260, 799–802 (1976).

Hughes, M. P. et al. Label-free, non-contact Estimation of resting membrane potential using dielectrophoresis. Sci. Rep. 14, 18477 (2024).

Aiuchi, T., Kamo, N., Kurihara, K. & Kobatake, Y. Significance of surface potential in interaction of 8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonate with mitochondria: fluorescence intensity and ζ potential. Bioelectrochem 16, 1626–1630 (1977).

Hato, M., Ueda, T., Kurihara, K. & Kobatake, Y. Change in zeta potential and membrane potential of slime mold physarum polycephalum in response to chemical stimuli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 426, 73–80 (1976).

Dukhin, A. S. Biospecific mechanism of double layer formation and peculiarities of cell electrophoresis. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem Eng. 73, 29–48 (1993).

Redmann, K., Jenssen, H-L. & Köhler, H-J. Experimental and functional changes in transmembrane potential and zeta potential of single cultured cells. Exp. Cell. Res. 87, 281–289 (1974).

Hughes, M. P. et al. Vm-related extracellular potentials observed in red blood cells. Sci. Rep. 11, 19446 (2021).

Hughes, M. P. The cellular zeta potential: cell electrophysiology beyond the membrane. Integr. Biol. 16, zyae003 (2024).

Al Bataineh, M. T. & Alazzam, A. Transforming medical device biofilm control with surface treatment using microfabrication techniques. Plos One. 18, e0292647 (2023).

Pierce, C. G. et al. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1494–1500 (2008).

Hoettges, K. F. et al. Ten–Second electrophysiology: evaluation of the 3DEP platform for high-speed, high-accuracy cell analysis. Sci. Rep. 9, 19153 (2019).

Tsai, T. et al. Electrical signature of heterogeneous human mesenchymal stem cells. Electrophoresis,10.1002/elps.202300202. (2024).

Hughes, M. P. et al. The platelet electrome: evidence for a role in regulation of function and surface interaction. Bioelectricity 4, 153–159 (2022).

Yang, M. & Brackenbury, W. J. Membrane potential and cancer progression. Front. Physiol. 4, 185 (2013).

Chacar, S. et al. Label-free, contactless measurement of membrane potential in excitable H9c2 cardiomyoblasts using ζ-potential. Meas. Sci. Tech. 35, 055701 (2024).

Skov, M. et al. The ClC-1 chloride channel inhibitor NMD670 improves skeletal muscle function in rat models and patients with myasthenia Gravis. Sci. Transl Med. 16, eadk9109 (2024).

Lee, W. & Lee, D. G. Potential role of potassium and chloride channels in regulation of silymarin-induced apoptosis in Candida albicans. IUBMB Life. 70, 197–206 (2018).

Huang, M. E., Chuat, J. C. & Galibert, F. A voltage-gated chloride channel in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol. Biol. 242, 595–598 (1994).

Nobile, C. J., Ennis, C. L., Hartooni, N., Johnson, A. D. & Lohse, M. B. A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, a proton pump inhibitor, and two calcium channel blockers inhibit Candida albicans biofilms. Microorganisms 8, 756 (2020).

Labeed, F. H. et al. Circadian rhythmicity in murine blood: electrical effects of malaria infection and anemia. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 994487 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. David Kadosh (UT Health San Antonio) for providing the cells used in this study.

Funding

This work was funded by Khalifa University grant FSU-2022-020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MJ performed the DEP and zeta experiments. MAB and SS performed the cell culture and biological analyses. MPH performed the overall analysis.MAB, HJ and MPH provided scientific expertise and supervised the project.All authors wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Author MPH holds shares in Deparator ltd, which manufactured one of the instruments used in this study. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, M.P., Al Bataineh, M.T., Sreedharan, S.P. et al. Vm and ζ-potential of Candida albicans corelate with biofilm formation. Sci Rep 15, 22475 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06371-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06371-5