Abstract

Hydrological models are an effective tool for the estimation of peak floods and runoff in planning water development and flood mitigation/adaptation. Continuous hydrologic modeling can determine the relationships between hydrologic processes and environmental changes over long time periods. Therefore, the selection of a theoretically robust and functionally reliable hydrological model is crucial for the effective management of flood risk within a basin. The Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) is one of the most widely used hydrological models for assessing the impacts of climate change on discharge in large basins. In contrast, the Hydrologic Engineering Centers’ Hydrologic Modeling System (HEC-HMS) has been one of the most rapidly evolving and promising hydrological models, with its latest version (v4.9) supporting both fully distributed and semidistributed hydrological modeling approaches. This study was conducted to compare the performances of SWAT and HEC-HMS in long-term continuous simulations in the Pearl River Basin, which is the second largest river basin in terms of discharge in China. For purposes of comparison, both models employed identical input data and comparable configurations. The results demonstrate that both models are capable of predicting river discharge at designated station satisfactories, with the Nash-Sutciffe coefficient exceeding 0.7. Benefiting from its elaborate use of the modified Soil Conservation Service (SCS) loss model and more advanced automatic calibration program, SWAT obtained more accurate results than HEC-HMS in the validation period. However, HEC-HMS is distinguished by its customizable options for constructing hydrological models, and it exhibits considerable potential for application in large-scale river basins such as the Pearl River Basin, enabling long-term, continuous hydrological simulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrologic processes denote all stages of the Earth’s water during cycles comprising rainfall, runoff, precipitation, subsurface water in a vodase layer and groundflow in aquifers. Climatology and geology are the two key factors that drive and characterize hydrologic processes1. In addition, anthropogenic impacts, including dam construction upstream and dam reclamation downstream, have an inhibitive effect on natural water cycles, such as the runoff distribution, sediment load and tidal levels2,3. Moreover, urbanization and industrialization significantly impact hydologic processes locally and globally through the alteration of land use and land cover change4. Therefore, an accurate assessment of the long-term response of climatic and anthropogenic impacts is crucial for human development and water resource management5.

Hydrological modeling uses a simplified representation of an existing hydrologic system to aid in water resource comprehension, forecasting and management. It is commonly employed to evaluate the hydrological response of a basin to precipitation and to provide guidance for managing water resources effectively6. Current state-of-the-art hydrological models have played an increasingly crucial role in flood simulation and risk assessment, predictive studies of social and economic development, and water resource planning and management. The most commonly used and advanced examples include the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT)7,8, VIC9,10, Storm Water Management Model (SWMM)11 and Hydrologic Engineering Center - Hydrologic Modeling System (HEC-HMS)12. Sahu et al.13 reviewed worldwide state-of-the-art hydrological models and compared ten models based on four essential criteria: open-source, applicable to Nexus, useful tutorials available and graphical interfaces. They found that HEC-HMS and SWAT are the only two models that met al.l four criteria. In the same year, Keller et al.14 evaluated twenty-one different hydrological and water quality models based on ten different criteria, and they claimed that three hydrologic models (including HEC-HMS), as well as two full hydrology and water quality models (including SWAT), stand out in terms of functionality, availability, applicability to a wide range of watersheds and scales, ease of implementation, and availability of support.

As the above two hydrological models (HEC-HMS and SWAT) have gained high recognition and widespread application internationally, the selection of a model that best interprets a hydrological process and accurately forecasts the future response to climate change is a challenging task. Recently, several scholars have used specific catchments to compare the two models for long-term continuous simulations15,16 and short-term storm event simulations17. However, their conclusions were mutually contradictory. According to Aryal et al.15 the accuracies of the two models are quite similar. However, Ismail et al.16 showed that the performance of HEC-HMS was better than that of SWAT. In contrast, a recent study by Ferreira et al.17 reached the opposite conclusion as that of Ismail et al.16. In their experiments, although the results obtained by SWAT in the calibration phase did not fit the observations, as did those generated by HEC-HMS, SWAT outperformed HEC-HMS in the validation phase.

Among those intercomparison cases, every study has dintinct configuration in their hydrological models. For example, Aryal et al.15 used the deficit and constant loss method in HEC-HMS, and Ferreira et al.17 used the SCS loss method in both SWAT and HEC-HMS. In our perspective, a set of identical configurations in different models is the prerequisite and foundation for an objective intermodel comparison. However, previous studies have rarely been able to systematically compare the different configurations and operational processes between SWAT and HEC-HMS from the perspective of model structure. The differences in the results of models in relation to their internal configurations and operational processes are also not well explained. Thus, the first objective of this study is to systematically compare the performances of HEC-HMS and SWAT through their applicability in long-term continuous hydrological simulations to provides guidance for the selection of the most appropriate model by management bodies. In particular, the different configurations and operational processes of the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) loss model within SWAT and HEC-HMS as well as their parameter calibration methods are highlighted. Second, this is the first use of HEC-HMS in such a large-scale basin covering an area of 442 000 km2the Pearl River Basin. Compared to SWAT, which is a widely used tool in China as a industry standard, HEC-HMS is significantly less commonly applied in the country. To the best of our knowledge, most applications of HEC-HMS have been in small basins18. Therefore, the second objective of this study is to evaluate the performance of HEC-HMS in a large-scale river basin and then identify the existing issues to be improved in future work.

The rest of the study is organized as follows: Sect. 2 introduces the investigated hydrological models and compares their differences. Section 3 provides information about the simulation area and data sources. The comparative results are presented with discussion in Sect. 4. Finally, conclusions are drawn in Sect. 5.

Introduction of the two hydrologial models

Hydrological models are tools used to simulate the movement of water on the Earth’s surface and within the soil and aquifer layers. These models are essential for understanding and managing water resources, predicting floods, and assessing the impacts of various factors, such as climate change and land use changes, on water systems. As two representative hydrological models, both HEC-HMS and SWAT have been well explored and validated in various regions worldwide. However, their differences have seldom been systematically demonstrated in previous studies. The following paragraphs introduce the two models separately and then make a comprehensive comparison between them.

HEC-HMS

HEC-HMS is the US Army Corps of Engineers’ Hydrologic Modeling System computer program developed by the Hydrologic Engineering Center19. This hydrologic modeling system is mainly composed of four types of submodels: loss model, direct runoff model, routing model and base-flow model. Like many other semidistributed hydrological models, HEC-HMS divides a large-scale basin into numerous subbasin elements, each of which separately and conceptually represents the comprehensive processes of infiltration, surface runoff, subsurface flow, and groundwater flow. All the subbasins are linked through river networks. Some classical evapotranspiration methods, such as the Priestly–Taylor method, have also been applied for long-term continuous simulations.

For each submodel, users are presented with a variety of methods. For instance, when estimating the impact of groundwater on runoff, users can select from four methods within the base model. These methods range from the most straightforward to the most complex and include the constant monthly method, the recession model, the linear reservoir method, and the nonlinear Boussinesq model. Among these methods, some (e.g., the recession model) are well suited for short-term hydrological modeling, while others (e.g., the constant monthly method and the linear reservoir method) are more appropriate for long-term hydrological modeling. Therefore, users can customize personalized submodels to build models of varying complexities based on their study areas, available data, research objectives and familiar knowledge. Figure 1 shows a comparison between a long-term simulation and short-term simulation.

Typical HEC-HMS representations of watershed runoff (cited from ref19).

In recent decades, HEC-HMS has been applied to a broad range of geographic areas to address various water resource problems20,21,22,23. It is considered to be adequately capable of simulating stream runoff in ungaged basins and analyzing runoff processes for water resource development and management24,25,26,27. Within the framework of HEC-HMS, selecting one appropriate loss model is crucial for successful simulation. The widely used loss models include the SCS, soil moisture accounting model (SMA)28,29,30, Green & Ampt31,32 and deficit and constant methods15,33. In addition to loss models, the specific methods used in direct runoff models, routing models and base-flow models are also critical for successful hydrologic simulations. Halwatura and Najim34 applied several transformation methods supplied by the direct runoff model to the Attanagalu Oya catchment and asserted that the Snyder unit hydrograph method simulated flows more reliably in their study catchment than did the Clark unit hydrograph method. Zelelew and Langon35 tested two kinds of loss methods for simulating runoff volume and peak flow in an ungauged catchment in northern Ethiopia and reported that the initial and constant loss methods and SCS unit hydrographs are better combinations than other methods. In this study, the SCS loss model, Clark’s unit hydrograph runoff model, Muskingum routing method and constant monthly baseflow model were selected as the model configurations to facilitate comparison with SWAT.

SWAT

SWAT is a physically based semidistributed hydrological model developed by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). It has been applied to long-term continuous simulations of hydrological processes, soil and water loss and soil chemical processes36. ArcSWAT is a SWAT extension within ArcGIS software. Once the topographic data are imported into ArcSWAT, the basin is divided into many small-scale subbasins, which are further divided into hydrological response units (HRUs) according to soil and land cover. As a long-term continuous hydrological model, SWAT provides several evapotranspiration methods, such as the Priestly–Taylor, Hargreaves and Penman‒Monteith methods. Figure 2 shows the water pathways in SWAT.

Pathways available for water movement in SWAT (revised from Neitsch et al.36).

In SWAT, a dynamic storage model is applied to simulate subsurface water, which is described by

.

where \(\:S{W}_{t}\) is the final soil water content (mm), \(\:S{W}_{0}\) is the initial soil water content (mm), t is the time (days), \(\:{R}_{day}\) is the amount of precipitation (mm), \(\:{Q}_{surf}\) is the amount of surface runoff (mm), \(\:{E}_{a}\) is the amount of evapotranspiration, \(\:{W}_{seep}\) is the amount of water entering the vadose zone from the soil (mm), and \(\:{Q}_{gw}\) is the amount of the return flow (mm).

In SWAT, the surface runoff from daily rainfall is estimated using a modified SCS curve number method, which estimates the amount of runoff based on local land use, soil type and antecedent moisture conditions. Compared to the curve number in the standard SCS loss model, the curve number in SWAT is not a static parameter but rather a dynamic state variable. The user only needs to provide an initial value CN217. As the model progresses, the curve number in SWAT may change over time, reflecting the varying conditions of the watershed. In China, SWAT is one of the most extensively employed hydrological models imported from abroad. Generally, this model is applied to (1) project the hydraulic response to future climate and human impacts37,38,39; (2) assess water and soil resource management40,41,42; and (3) estimate groundwater recharge in plains43,44,45. Due to the availability of open-source code, some scholars have modified and improved the SWAT modules to adapt to their specific studies46,47,48.

Comparison of HEC-HMS and SWAT

Although both hydrological models share similar underlying physical mechanisms, they are different in many aspects. First, the basic computational unit of HEC-HMS is the subbasin, and it is the HRU for SWAT. The HRU is essentially a further division within each subbasin and is one of the most distinctive characteristics of SWAT. This means that more than one land use and soil property can be adopted within a subbasin in SWAT. In this study, although the PRD was divided into the same 1200 subbasins for both models according to topography, 10,167 HRUs based on land use and land cover, soil type and management practices were further defined for SWAT. Second, as a flexible-structure model system, HEC-HMS provides abundant options for each type of submodel in the hydrological process (Table 1). Thus, it can be applied to both long-term continuous simulation and short-term event simulation (shown in Fig. 1). For example, in terms of the loss model within HEC-HMS, users have the flexibility to select very straightforward submodels, such as the SCS loss model, or they can opt for the more complex SMA model for long-term simulations. In contrast, SWAT has a more compact structure but thus provides very limited choices of submodels representing its intermediate process (shown in Fig. 2). Third, HEC-HMS applies several baseflow models to represent the effect of groundwater. Among these models, both the recession and constant monthly methods are empirical and straightforward, which means that the derived baseflow may not adhere to the mass conservation law. In contrast, the linear reservoir method is a more physically based approach that conforms to the principles of water balance. In comparison, SWAT utilizes water balance equations throughout subsurface layers, including the soil vadose zone and groundwater aquifers. This approach allows SWAT to differentiate the groundwater system into shallow and deep aquifers49. For example, the water balance in shallow aquifers is achieved between percolation from soil percolation into deep aquifers, phreatic evaporation, base flow and artificial exploitation by pumping. Initially, the groundwater model was employed to calculate the base flow into the main channel or reach of numerous basins. In recent years, several studies50 have used the groundwater model in SWAT to estimate groundwater recharge in plains.

The SCS loss model, developed by the USDA in 1954, is an empirically based model widely used globally to estimate surface runoff (US Soil Conservation Service, 1954). However, although the same SCS model is utilized in both HEC-HMS and SWAT, it operates in completely different ways within each respective model. In HEC-HMS, the SCS loss model keeps the curve number unvariable during the entire simulation period. Consequently, in theory, long-term hydrological processes cannot be replicated due to the persistent changes in land use and soil moisture conditions, which alter the curve number. In this study, we conducted each simulation within a one-year timeframe to account for the annual changes in land use while neglecting the seasonal variations in soil moisture. In comparison, the curve number in SWAT is constantly adjusted in the simulation (as shown in Fig. 2) according to the water moisture content in the soil, which is also constantly updated through the soil water balance computation. Accordingly, the curve number in SWAT varies in conjunction with the soil moisture content for long-term continuous simulations36.

Another significant difference between the two models is the optimization program for parameter calibration. HEC-HMS provides two trial-and-error search algorithms: the univariate gradient search algorithm and the Nelder and Mead simplex search algorithm. The univariate gradient method evaluates and adjusts one parameter at a time while holding the other parameters constant. The Nelder and Mead method uses a downhill simplex to evaluate all parameters simultaneously and determine which parameter to adjust. SWAT provides a plug-in component, SWAT-CUP, to calibrate parameters. SWAT-CUP automatic calibration is conducted using the sequential uniform fitness-based independent combinatorial search version 2 algorithm (SUFI-2)51. In comparing the two models for parameter calibration, SWAT exhibits superiority over HEC-HMS due to the limitations of the Nelder‒Mead simplex search algorithm on local optimal solutions, as noted by Duan et al.52 rather than global optima. In contrast, SUFI-2 is a metaheuristic algorithm designed for solving combinatorial optimization problems. It draws inspiration from natural selection and genetic algorithms but employs a fitness-based search mechanism instead of traditional genetic operators such as crossover and mutation. Therefore, it can be used to obtain the global optimal values of the parameters in SWAT. The subsequent simulation results prove the superiority of the SUFI-2 algorithm in SWAT.

Study area and data

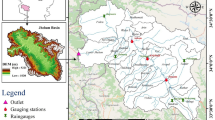

The Pearl River Basin (PRB), consisting of the West River, North River and East River subbasins, is the second largest river basin in terms of discharge in China (Fig. 3). Among the average total discharge per year, 238 km3 is from the West River, 39.4 km3 is from the North River, and 23.8 km3 is from the East River. The discharge from the West River is approximately four times greater than the combined flow of the North River and the East River. As the largest river basin in South China, the PRB covers a drainage area of 4.42 × 105 km2. Among them, the West River covers more than 3/4 of the total area of the PRB, and the others cover less than 1/4 of the total area.

As shown in Fig. 3, the topography of the PRB decreases from the northwest to the southeast delta area. As the origin of the West River, the region in the northwest is primarily characterized by mountainous terrains dominated by steep hill slopes and deep valleys. The cities are mainly concentrated on flat plains in the lower reaches of the Pearl River Basin, namely, the Pearl River Delta. Figure 4 shows the land use and land cover of the Pearl River Basin and the soils. The soils in the Pearl River Basin are diverse and are primarily influenced by the sediment transport of the river and the climate of the region. The predominant soil types in the Pearl River Basin include ferralisol, skeletol primitive soil, anthrosol and luvisol soils.

The PRB is situated between subtropical and tropical zones, with mean annual precipitation ranging from 1200 to 2200 mm, ranking first among the river basins in China. Figure 5 shows the distribution of the mean annual precipitation from 2006 to 2011, which shows that the main precipitation zone is located in the East River, North River and eastern parts of the West River Basin.

In summary, the Pearl River Basin exhibits high spatial heterogeneity in terms of land use, soil properties, and precipitation characteristics, necessitating the use of distributed hydrological models for simulation. SWAT and HEC-HMS can both operate in a semidistributed form through subbasin delineation. For ease of comparison, we employ the same subbasin delineation and partitioning scheme for the two models (see 1200 subbasins in Fig. 6). It should be noted that the new version (v4.9) of HEC-HMS can run in both fully distributed and semidistributed forms; in this study, we used its semidistributed forms for comparison with SWAT.

The DEM derived from the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer Global (ASTER) GDEM was utilized to construct the primary topography of the basin terrain. Some DEM preprocessing steps, such as sink filling, flow accumulation, drainage network extraction and subbasin division, were conducted using the GIS desktop tool. Eventually, a total of 1200 subbasins were formed (Fig. 6). The soil map was obtained from the HWSD (Harmonized World Soil Database) at a scale of 1:1,000,000, which is composed of the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) and IIASA. The land use and land cover data were obtained from remote sensing data from the Resource and Environmental Science Data Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The meteorological data, including daily precipitation, temperature, relative humidity and wind speed, were obtained from CFSR (Climate Forecast System Reanslysis) data ranging from 1979 to 2014. For calibrating and validating the models, the hydrological data series (2006–2011) of water discharge in the PRB were collected from the hydrological yearbooks of the People’s Republic of China. Six hydrological stations (indicated in Fig. 3) were used to calibrate and verify the hydrological models. The four stations from upstream to downstream included Liuzhou (LZ), Dahuangjiangkou (DHK), Gaoyao (GY), and Makou (MK), which control runoff from the West River Basin. The Shijiao (SJ) station controls runoff from the North River Basin, and the Boluo (BL) station controls runoff from the East River Basin.

The Nash-Sutcliffe coefficient of efficiency (NSE) is a metric widely used in hydrology to evaluate the performance of hydrological models. Here, we use the NSE to quantitatively evaluate the agreement between the simulated and observed values. Saleh et al.53 suggested four ratings to divide the model performance according to the NSE values: very good (0.75 < NSE ≤ 1), good (0.65 < NSE ≤ 0.75), satisfactory (0.50 < NSE ≤ 0.65) and unsatisfactory (NSE ≤ 0.5).

Results

Monthly streamflow records from a six-year period (2006–2011) were employed to calibrate and validate the hydrological models. The first four years of data (2006–2009) were utilized for model calibration, whereas the subsequent two years (2010–2011) were employed for validation purposes. Before calibration, sensitivity analysis was performed on the parameters of each model, which served as an auxiliary tool to aid in the calibration process. SWAT provides a module that conducts sensitivity analysis using the Latin Hypercube Sampling with One-factor-At-a-Time (LH-OAT) method. LH-OAT is a powerful and effective method that combines the advantages of the LH sampling method (optimally covering the sampling cube with the least number of sampling times) and the OAT method (the output variation can be clearly attributed to the change in a single parameter at the sampling point). HEC-HMS does not include a built-in module for sensitivity analysis, so we had to conduct it manually. In this study, we employed the Morris screening method54 to determine the most significant parameters that affect a specific response variable. Figure 7 shows the sensitivity analysis results using the Morris screening method of Wen55.

Sensitivity analysis results using the Morris screening method (Wen55).

Table 2. Most sensitive parameters in HEC-HMS and SWAT.

Based on the parameter importance identified through sensitivity analysis, a hybrid approach of manual and automatic calibration was employed in HEC-HMS to refine the model parameters. This integration was necessary because automatic calibration alone in HEC-HMS was unable to identify global optimal values when dealing with a vast number of subbasins, such as the 1200 subbasins in the Pearl River Basin. In comparison, the SWAT-CUP automatic calibration program performed well in search of the optimal parameter values in SWAT. Ferreira et al.17 compared the performance of HEC-HMS with that of SWAT in fluvial flow simulation and reported that due to the greater automation of the SWAT simulation procedures and the optional calibration parameters, the calibration and validation processes in SWAT were less laborious. Our experience of calibration between the two models aligns with their statement.

Figure 8 shows the results of the two models when comparing the observations from the six monitoring stations. It is evident that both models are capable of producing reasonable results, accurately representing the annual fluctuations in runoff, including different interannual peak values. Table 3 shows the NSE values at the six stations in the calibration and validation periods. During the calibration period, the accuracies of both models are sufficiently high and much greater than the ‘very good’ rating. In particular, at four stations (GY, MK, SJ and BL), the accuracy of HEC-HMS is slightly greater than that of SWAT. However, in the validation period, the accuracy of HEC-HMS is slightly lower than that of SWAT. Specifically, HEC-HMS overestimates the peak discharge in 2010 at the LZ, SJ and BL stations. Nonetheless, it still achieves ‘good’ or ‘very good’ ratings, with NSE values exceeding 0.65 and 0.75, respectively. This indicates that both models perform well in terms of accuracy and reliability in predicting runoff, as these NSE values are considered high enough to reflect good agreement between the simulated and observed data.

Discussion

Although the two models both rank ‘very good’ or ‘good’ according to the NSE classification, there are still different characteristics in the modeling results. Although both models perform quite similarly during the calibration period, SWAT yields better results during the validation period, with the exception of the GY station. By comparing our results with those of similar studies worldwide, it is found that Ferreira et al.17 obtained similar results for the two models. In their experiments, although the simulated streamflow from SWAT during the calibration period did not fit as well with observed data as those generated by HEC-HMS, SWAT demonstrated superior performance in simulating flows during the validation period. Ferreira et al.17 attributed this to the greater variety of parameters in SWAT, which increased its ability to simulate the provided flows. According to our sensitivity analysis shown in Table 2, the more diverse parameters are mainly because SWAT’s representation of soil flow and groundwater is more complex than that of HEC-HMS, which contributes to the accuracy of the results, especially in river basins where groundwater recharge plays a significant role.

However, in our opinion, the main reason for the difference between the two models is not only this but also the different implementations of the SCS loss model in HEC-HMS and SWAT. The curve number in HEC-HMS is a parameter that remains constant throughout the simulation period after calibration. As the value of the curve number from the US-based lookup table is far from the realistic values in China (Lian et al., 2020), Wen55 proposed a new method to revise the curve number values based on the calibration results in the PRB. Figure 9 shows the spatial distribution of the calibrated curve number in the PRB. In comparison, the curve number in SWAT is an intermediate state variable that is continuously adjusted according to the soil moisture content during the simulation (Fig. 2). The soil moisture content is also a dynamic state variable that reflects the balance between surface flow and subsurface water movement (e.g., soil interwater and groundwater). In long-term continuous hydrologic simulations, the dynamic adjustable curve number is more reasonable than the constant curve number. Therefore, in terms of its mechanism, and with the superiority of the SUFI-2 algorithm for parameter calibration (introduced in Sect. 2.3), SWAT outperforms HEC-HMS at most stations during the validation period.

With reference to similar studies that also compared SWAT and HEC-HMS, Ferreira et al.17 claimed that while both software systems were satisfactorily able to simulate the flow, SWAT presented greater potential for use by management and urban planning in the management of risks. The primary distinctions between our study and the work by Ferreira et al.17 are the scale of the basin and the duration of the hydrological simulation. They utilized a small basin with an area of 536.97 km2 to simulate a short-term event process. In comparison, our study basin is approximately 1,000 times larger than Ferreira et al.17 area, and our simulation encompasses a long-term, continuous hydrological process rather than a short-term event-based analysis. This spatiotemporal difference in scale may contribute to variations in model performance. In a separate study, Ismail et al.16 demonstrated that HEC-HMS outperformed SWAT in a 30-year continuous simulation. The authors attributed this to the complexity of the SWAT input parameters, which rendered calibration difficult. Aryal et al.15 reached a similar conclusion when they compared HEC-HMS with SWAT for uncertainty analysis under climate change. However, similar to Ferreira et al.17 both of these cases were also applied to small-scale basins. A small basin means that the basin needs to be divided into a very limited number of subbasins (less than 100), which is much less than our number of subbasins (1200 subbasins). Although SWAT is commonly used for large-scale basin studies, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first instance where HEC-HMS has been utilized for a large-scale basin comprising many subbasins. Consequently, some disadvantages of automatic calibration functions in HEC-HMS have begun to emerge in our case, which significantly decrease the efficiency and prediction accuracy in dealing with such a large number of subbasins and rivers.

Therefore, from our perspective, SWAT is still the most stable and mature hydrological model used for long-term continuous simulations in large-scale river basins in China. SWAT is much more sophisticated than HEC-HMS in the representation of soil interflow within the vadose zone and groundwater flow within the aquifers. To date, SWAT remains the most extensively utilized hydrological model for assessing not only surface flow but also groundwater recharge in plains. This model has been demonstrated to have a distinct advantage over other methods due to its ability to account for the spatial variability of influenced factors compared with other methods48.

Nonetheless, through its application in large-scale river basins, the performance of HEC-HMS is excellent given its imperfect automatic calibration program and simplified representation of the subsurface mechanism. Our case study shows that the deficiency of the current automatic calibration functions is the major factor that constrains the application of HEC-HMS in large-scale river basins. If some promising automatic calibration methods are integrated into automatic calibration programs, HEC-HMS has great potential to become another commonly used large-scale basin hydrological model in China. It is also worth noting that, for the sake of convenience in intercomparison, both HEC-HMS and SWAT utilize the SCS loss model in this study. In practice, HEC-HMS has adequate loss models to replace the SCS model for conducting long-term simulations (shown in Table 1). For example, the SMA model is more advanced in its representation of long-term water movement and better aligns with the continuous nature of hydrological processes29. However, the application of the SMA model can be more challenging because the SMA model requires the calibration of more parameters than does the SCS model. The current algorithms for parameter calibration (e.g., the Nelder‒Mead simplex search algorithm) within HEC-HMS may not be as robust or perfected to support the calibration of the SMA model. Furthermore, the SMA model is supposed to replace the SCS model in conjunction with the linear reservoil base flow model to better represent the interflow and groundflow after several state-of-the-art optimization algorithms, such as SUFI-2, the SCE-UA, and PSO56 are integrated into HEC-HMS.

As a model that has undergone rapid development in recent years, HEC-HMS has distinct advantages over SWAT. It provides a broader range of submodule options, which cover simulating both long-term and short-term hydrological processes. Additionally, it provides fully distributed hydrological simulation methods based on grids, thereby offering enhanced compatibility with remote sensing data. Therefore, HEC-HMS is one of the most promising hydrological models in the era of remote sensing hydrology.

Water resource management needs to predict future water availability at the watershed scale using hydrological models. However, there are many models that differ in terms of the approach and applicable area. The selection of a model that best explains a hydrological process in a specific area is a challenging task. Several previous studies have compared more than 10 different models to better understand the strengths and weaknesses of these models14. Similar to those previous studies, our work also provides new insight to water resource managers and decision-makers about how to choose an appropriate hydrological model to assist in flood prediction and risk management in a similar-scale watershed.

The study has limitations. Given the size and complexity of the PRB, this seems insufficient to use only six stations to calibrate and validate the model. If the objective is to systematically analyze the PRB’s hydrological processes and underlying mechanisms, the current model framework would require additional observational data from more spatially distributed stations to ensure robustness. However, considering this study’s primary focus on evaluating model applicability and comparative performance assessment, the existing sparse observational stations has nevertheless enabled us to adequately address these core research objectives. In future, we will incorporate more monitoring stations to enhance the model’s capacity for replicating real-world hydrological dynamics with greater fidelity.

Conclusions

A long-term continuous simulation was conducted for a large-scale river basin using two hydrological models, HEC-HMS and SWAT. The results demonstrated that both models performed satisfactorily during the calibration and validation processes. As a classical semidistributed hydrology model, SWAT yielded slightly more accurate results than did HEC-HMS during the validation period. This can be attributed to the continuously adjustable SCS loss model and more sophisticated subsurface representations of the water balance in SWAT. Furthermore, the SUFI-2 algorithm within SWAT surpassed the simplex method used in HEC-HMS in regard to searching for optimal parameters during model calibration. However, the performance rankings of ‘very good’ and ‘good’ demonstrated that HEC-HMS is applicable for long-term continuous simulations in large-scale basins. As a rapidly evolving hydrological model, newer versions of HEC-HMS are capable of incorporating more advanced submodels, offering fully distributed gridded methods to simulate hydrological processes, although its performance should be further evaluated against benchmarks. Future efforts should focus on refining the auto-calibration algorithm to reduce the labor intensity during the calibration phase and on enhancing the physical representation within the subsurface layers, thereby making the calculations of the water content in the aquifer and vadose zones more rational.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sharma, A., Baruah, A., Mangukiya, N., Hinge, G. & Bharali, B. Evaluation of gangetic Dolphin habitat suitability under hydroclimatic changes using a coupled hydrological-hydrodynamic approach. Ecol. Inf. 69, 101639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101639 (2022).

Duncombe, J. Not your childhood water cycle. Eos 103, 499. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EO220499 (2022).

Wu, C. S., Yang, S. L. & Lei, Y. P. Quantifying the anthropogenic and Climatic impacts on water discharge and sediment load in the Pearl river (Zhujiang), China (1954–2009). J. Hydrol. 452–453, 190–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.05.064 (2012).

Zhang, L., Yin, J., Jiang, Y. & Wang, H. Relationship between the hydrological conditions and the distribution of vegetation communities within the Poyang lake National nature reserve, China. Ecol. Inf. 11, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2012.05.006 (2012).

Zhao, S. et al. Predictions of runoff and sediment discharge at the lower yellow river Delta using basin irrigation data. Ecol. Inf. 78, 102385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102385 (2023).

Zscheischler, J., Mahecha, M. D., Harmeling, S. & Reichstein, M. Detection and attribution of large Spatiotemporal extreme events in Earth observation data. Ecol. Inf. 15, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2013.03.004 (2013).

Taia, S. et al. Comparing the ability of different remotely sensed evapotranspiration products in enhancing hydrological model performance and reducing prediction uncertainty. Ecol. Inf. 78, 102352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102352 (2023).

Tripathi, M. P., Raghuwanshi, N. S. & Rao, G. P. Effect of watershed subdivision on simulation of water balance components. Hydrol. Process. 20, 1137–1156. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.5927 (2006).

Liang, X., Xie, Z. & Huang, M. A new parameterization for surface and groundwater interactions and its impact on water budgets with the variable infiltration capacity (VIC) land surface model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 8613. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD003090 (2003).

Yan, D., Werners, S. E., Ludwig, F. & Huang, H. Q. Hydrological response to climate change: the Pearl river, China under different RCP scenarios. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 4, 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2015.06.006 (2015).

Ghosh, I. & Ferdi, L. H. Effects of Spatial resolution in urban hydrologic simulations. J. Hydraul Eng. 17, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0000405 (2012).

Zhang, H. L., Wang, Y. J., Wang, Y. Q., Li, D. X. & Wang, X. K. The effect of watershed scale on HEC-HMS calibrated parameters: a case study in the clear creek watershed in Iowa. US Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 2735–2745. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-2735-2013 (2013).

Sahu, M. K., Shwetha, H. R. & Dwarakish, G. S. State-of-the-art hydrological models and application of the HEC-HMS model: a review. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 9, 3029–3051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-023-01704-7 (2023).

Keller, A. A., Garner, K., Rao, N., Knipping, E. & Thomas, J. Hydrological models for climate-based assessments at the watershed scale: a critical review of existing hydrologic and water quality models. Sci. Total Environ. 867, 161209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.161209 (2023).

Aryal, A., Shrestha, S. & Babel, M. S. Quantifying the sources of uncertainty in an ensemble of hydrological climate-impact projections. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 135, 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-017-2359-3 (2019).

Ismail, H., Kamal, M. R., Hin, L. S. & Abdullah, A. F. Performance of HEC-HMS and ArcSWAT models for assessing climate change impacts on streamflow at Bernam river basin in Malaysia. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 28, 1027–1048 (2020).

Ferreira, R. G. et al. Performance of hydrological models in fluvial flow simulation. Ecol. Inf. 66, 101453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101453 (2021).

Oleyiblo, J. O. & Li, Z. J. Application of HEC-HMS for flood forecasting in Misai and wan’an catchments in China. Water Sci. Eng. 3, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.3882/j.issn.1674-2370.2010.01.002 (2010).

USACE—US Army Corps of Engineers. Hydrologic Modeling System HEC-HMS Technical Reference Manual CPD-74B (Hydrologic Engineering Center, 2000).

Györi, M. M. & Haidu, I. Unit hydrograph generation for ungauged subwatersheds. Case study: the Monoroştia river, Arad County. Romania Geogr. Tech. 14, 23–29 (2011).

Kabeja, C. et al. The impact of reforestation induced land cover change (1990–2017) on flood peak discharge using HEC-HMS hydrological model and satellite observations: a study in two mountain basins. China Water. 12, 1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12051347 (2020).

Lin, Q., Lin, B., Zhang, D. & Wu, J. Web-based prototype system for flood simulation and forecasting based on the HEC-HMS model. Environ. Model. Softw. 158, 105541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2022.105541 (2022).

Lin, Q., Lin, B., Zhang, D., Wu, J. & Chen, X. HMS-REST v1.0: a plugin for the HEC-HMS model to provide restful services. Environ. Model. Softw. 170, 105860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2023.105860 (2023).

Gumindoga, W., Rwasoka, D. T., Nhapi, I. & Dube, T. Ungauged runoff simulation in upper manyame catchment, zimbabwe: application of the HEC-HMS model. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C. 100, 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2016.05.002 (2017).

Panigrahi, B., Choudhari, K. & Paul, J. C. Watershed planning using interactive multi objective linear programming approach: a case study academic excellence view project simulation of rainfall-runof process using HEC-HMS model for balijore Nala watershed, odisha, India. Int. J. Geomat. Geosci. 5, 253–265 (2014).

Sampath, D., Weerakoon, S. & Herath, S. HEC-HMS model for runoff simulation in a tropical catchment with intra-basin diversions case study of the Deduru Oya river basin, Sri Lanka. Eng. J. Inst. Eng. Sri Lanka. 48, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4038/engineer.v48i1.6843 (2015).

Sheng, F., Liu, S., Zhang, T., Liu, G. & Liu, Z. Quantitative assessment of the impact of precipitation and vegetation variation on flooding under discrete and continuous rainstorm conditions. Ecol. Indic. 144, 109477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109477 (2022).

Azizi, S., Ilderomi, A. R. & Noori, H. Investigating the effects of land use change on flood hydrograph using HEC-HMS hydrologic model (case study: Ekbatan Dam). Nat. Hazards. 109, 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04830-6 (2021).

Chu, X. & Steinman, A. Event and continuous hydrologic modeling with HEC-HMS. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 135, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9437(2009)135:1(119) (2009).

El Khalki, E. M. et al. Challenges in flood modeling over data-scarce regions: how to exploit globally available soil moisture products to estimate antecedent soil wetness conditions in Morocco. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 2591–2607. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-20-2591-2020 (2020).

De Silva, M. M. G. T., Weerakoon, S. B. & Herath, S. Modeling of event and continuous flow hydrographs with HEC–HMS: case study in the Kelani river basin, Sri Lanka. J. Hydraul Eng. 19, 800–806. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0000846 (2014).

Kure, S., Jang, S., Ohara, N., Kavvas, M. L. & Chen, Z. Q. Hydrologic impact of regional climate change for the snowfed and glacierfed river basins in the Republic of tajikistan: hydrological response of flow to climate change. Hydrol. Process. 27, 4057–4070. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9535 (2013).

Meenu, R., Rehana, S. & Mujumdar, P. P. Assessment of hydrologic impacts of climate change in Tunga–Bhadra river basin, India with HEC-HMS and SDSM. Hydrol. Process. 27, 1572–1589. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9220 (2012).

Halwatura, D. & Najim, M. M. M. Application of the HEC-HMS model for runoff simulation in a tropical catchment. Environ. Model. Softw. 46, 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2013.03.006 (2013).

Zelelew, D. G. & Langon, S. Selection of appropriate loss methods in HEC-HMS model and determination of the derived values of the sensitive parameters for un-gauged catchments in Northern Ethiopia. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 18, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2019.1672701 (2020).

Neitsch, S. L., Arnold, J. G., Kiniry, J. R., Srinivasan, R. & Williams, J. R. Soil and Water Assessment Tool Theoretical Documentation, Version 2005 (USDA-ARS Grassland, Soil and Water Research Laboratory, 2005).

Gwal, S., Gupta, S., Sena, D. R. & Singh, S. Geospatial modeling of hydrological ecosystem services in an ungauged upper Yamuna catchment using SWAT. Ecol. Inf. 78, 102335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102335 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Improvement of simulating sub-daily hydrological impacts of rainwater harvesting for landscape irrigation with rain barrels/cisterns in the SWAT model. Sci. Total Environ. 798, 149336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149336 (2021).

Xu, Y. P., Zhang, X., Ran, Q. & Tian, Y. Impact of climate change on hydrology of upper reaches of qiantang river basin, East China. J. Hydrol. 483, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2013.01.004 (2013).

Jordan, S., Quinn, J., Zaniolo, M., Giuliani, M. & Castelletti, A. Advancing reservoir operations modelling in SWAT to reduce socio-ecological tradeoffs. Environ. Model. Softw. 157, 105527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2022.105527 (2022).

Neumann, A. et al. Implementation of a watershed modelling framework to support adaptive management in the Canadian side of the lake Erie basin. Ecol. Inf. 66, 101444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101444 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. A generalized reservoir module for SWAT applications in watersheds regulated by reservoirs. J. Hydrol. 616, 128770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128770 (2023).

Awan, U. K. & Ismaeel, A. A new technique to map groundwater recharge in irrigated areas using a SWAT model under changing climate. J. Hydrol. 519, 1368–1382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.08.049 (2014).

Githui, F., Selle, B. & Thayalakumaran, T. Recharge Estimation using remotely sensed evapotranspiration in an irrigated catchment in Southeast Australia. Hydrol. Process. 26, 1379–1389. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.8274 (2012).

Perrin, J. et al. Assessing water availability in a semi-arid watershed of Southern India using a semi-distributed model. J. Hydrol. 460–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.07.002 (2012).

Kim, J., Her, Y., Bhattarai, R. & Jeong, H. Improving nitrate load simulation of the SWAT model in an extensively tile-drained watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 904, 166331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166331 (2023).

Lai, Z., Li, S., Deng, Y., Lv, G. & Ullah, S. Development of a polder module in the SWAT model: SWATpld for simulating polder areas in South-Eastern China. Hydrol. Process. 32, 1050–1062. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.11477 (2018).

Zhang, X., Ren, L. & Kong, X. Estimating Spatiotemporal variability and sustainability of shallow groundwater in a well-irrigated plain of the Haihe river basin using SWAT model. J. Hydrol. 541, 1221–1240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.08.030 (2016).

Arnold, J. G., Allen, P. M. & Bernhardt, G. A comprehensive surface-groundwater flow model. J. Hydrol. 142, 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(93)90004-S (1993).

Zhang, X., Srinivasan, R., Arnold, J., Izaurralde, R. C. & Bosch, D. Simultaneous calibration of surface flow and baseflow simulations: a revisit of the SWAT model calibration framework. Hydrol. Process. 25, 2313–2320. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.8058 (2011).

Abbaspour, K. C. SWAT-Calibration and Uncertainty Programs (CUP)—A User Manual (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, 2015).

Duan, Q., Sorooshian, S. & Gupta, V. Effective and efficient global optimization for conceptual rainfall-runoff models. Water Resour. Res. 28, 1015–1031. https://doi.org/10.1029/91WR02985 (1992).

Saleh, A. et al. Application of SWAT for the upper North Bosque watershed. Trans. ASAE. 43, 1077–1087 (2000).

Morris, M. D. Factorial sampling plans for preliminary computational experiments. Technometrics 33, 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00401706.1991.10484804 (1991).

Wen, Y. Hydrological Modeling Method and the Hydrologic Response of Watershed based on HEC-HMS. Nanjing Normal University, Master’s thesis, China (2023).

Chen, Q., Gou, S., Qin, D. & Zhou, Z. A high efficiency auto-calibration method for SWAT model. J. Hydraul Eng. 41, 113–119 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (42171465; 42171406; 42230406), and Key Laboratory of Ministry of Education for Coastal Disaster and Protection, Hohai University (202218).

Funding

Study design, analysis and data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhuo Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Resources and Writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z. Performance of long-term continuous hydrological models in fluvial flow simulation in a large-scale river basin. Sci Rep 15, 22124 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06387-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06387-x