Abstract

Slash pine (Pinus elliottii Engelm.) is an economically significant tree species valued for its timber and resin production. Establishing a somatic embryogenesis system is essential for the effective utilization of slash pine. This study aims to develop an optimized cultivation system for the long-term proliferation of embryogenic callus (EC) in slash pine. The study used the EC induced from immature zygotic embryos as materials to investigated the effects of plant growth regulators (PGRs), subculture cycles, and subculture durations on the EC proliferation coefficient and the number of somatic embryos (SE). Additionally, we monitored the changes in the proliferation coefficient, the number of SE, and physiological and biochemical indicators of EC during long-term proliferation. The EC proliferation coefficient reached its highest value (7.65) when the DCR medium was supplemented with 1.0 mg/L 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 1.0 mg/L 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA). Refreshing the culture medium every 14 days, EC maintaining proliferation coefficient (4.05) and embryogenic potential for approximately three year (980 d), but the number of somatic embryos was low and significantly declined after 140 days.The additional supplementation of 1.0 mg/L 2- (1-naphthyl) acetic acid (NAA) to the original proliferation medium further enhanced SE induction, achieving a maximum of 143.25 SE per gram of EC. Under the optimal proliferation culture conditions, EC was subcultured for 392 days, with no significant differences observed in the proliferation coefficient and the number of SE. The results of correlation and path analyses between physiological indicators and proliferation coefficient indicate that the proliferation coefficient of EC is mainly related to the content of storage substances (starch and soluble sugars) and the activities of redox-related enzymes (POD and CAT). The optimized long-term proliferation culture system for EC in slash pine provides an efficient approach to enhance the production of EC and SE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Slash pine (Pinus elliottii Engelm.) an economically valuable tree species, and is characterized by strong adaptability, high resistance, rapid growth, and high resin yield, it native to the wetlands and coastal regions of the southeastern United States, now it has been widely introduced to various parts of the world and plays a significant role in global forestry production1,2. And it was introduced to China in the early 20th century, and has become an important economic tree species in Jiangxi Province3. However, traditional breeding methods face challenges such as long breeding cycles and the offspring of hybrid breeding have genetic instability, which hinder their ability to meet the demands of large-scale production. Somatic embryogenesis is a tissue culture technique that induces somatic cells to re-enter the cell cycle and generate new embryos, similar to zygotic embryogenesis without fertilizatio4,5. Compared to conventional propagation, somatic embryogenesis enables faster production of new plants for research and commercial applications and is considered a viable approach to address the supply-demand imbalance of elite species5,6.

Since the first successful application of somatic embryos on Picea abies by Hakman et al.7 in 1985, this technology has been extended to various conifer species including Abies nebrodensis8Pinus koraiensis9,10Picea glauca11Larix decidua12Abies nordmanniana4Pinus pinaster13. Furthermore, somatic embryogenesis technology system of slash pine is also being actively explored. In 1989, Jain et al.14 initiated the study of somatic embryogenesis in slash pine by using immature zygotic embryos as experimental material, successfully inducing embryogenic callus (EC) and then producing somatic embryos (SE). Subsequently, Hu et al.5Liao and Amerson15Newton et al.16and Tang et al.17 obtained regenerated plants of slash pine. Additionally, Yang et al.6 found that the adding 5 mg/L abscisic acid (ABA) to the suspension proliferation culture medium significantly increased SE yield. Despite these advancements, large-scale SE production in slash pine remains challenging due to the induction rate of EC in slash pine can only reach a maximum of 33%18, and the longest duration for maintaining EC is 6 months. Additionally, the differentiation efficiency of EC into SE is limited, and the proliferation capacity and embryogenic potential of EC are difficult to sustain over the long term19,20.

The embryonic maintenance and somatic embryo yield of EC is an important evaluation index in the large-scale breeding of conifer SE21. Establishing an efficient and stable long-term proliferation system for EC is a key step in achieving the industrialized production of somatic embryos22,23. For example, yield and quality of mature somatic embryos in Pinus pinaster, is strongly dependent on the EC line24. However, long-term subculture often leads to a decline in embryogenic potential and abnormal morphological changes in EC, posing a major challenge for sustained SE production25,26,27. Studies indicate that optimizing culture conditions, such as the types and concentrations of plant growth regulators (PGRs), culture cycle, and sucrose concentration, can enhance EC proliferation efficiency and maintain embryogenic capacity28,29,30. For instance, in Picea koraiensis, a combination of 0.21 mg/L BA, 0.20 mg/L KT, 1.85 mg/L NAA, and 20 g/L sucrose significantly improved EC proliferation efficiency31. In Pinus taeda, media supplemented with 0.1 mg/L 2,4-D, 0.05 mg/L BA, and 0.05 mg/L KT, or 0.5 mg/L NAA, 0.05 mg/L BA, and 0.05 mg/L KT, proved effective for EC maintenance26.

Somatic embryogenesis is a complex process that involves energy storage and the cooperative action of antioxidant enzymes, which together regulate EC proliferation as well as the formation and development of SE32. Storage compounds, such as starch, soluble sugars, and soluble proteins, are fundamental to cellular metabolism, and reactive oxygen species and redox homeostasis are also crucial for EC proliferation and differentiation33. Investigating the physiological mechanisms underlying somatic embryogenesis is essential for the precise regulation of this process. For example, phytosulfokine has been shown to maintain reactive oxygen species homeostasis by reducing peroxidase activity during early SE induction, thereby promoting SE formation in Cunninghamia lanceolata34and phytosulfokine has been demonstrated to facilitate the transition of embryogenic masse from pro-embryogenic mass I(PEMI)to PEMII or PEMIII stages in Pinus massoniana, and increased the accumulation of soluble sugars, soluble proteins, and starch35. In slash pine, significant variations in soluble proteins, soluble sugars, starch content, and antioxidant enzyme activities (POD, SOD, CAT) have been observed among EC cell lines, though no clear correlation with embryogenic potential has been established36. The physiological and biochemical responses of slash pine EC during long-term proliferation remain poorly understood, representing a critical knowledge gap.

This study addresses this gap by optimized long-term EC proliferation system for slash pine, examining the effects of PGRs, subculture cycles, and monitoring the changes in metabolite content indicators (soluble sugars, starch, soluble proteins), antioxidant enzyme activity indicators (SOD, POD, and CAT) on EC proliferation and SE production. The findings of this study are expected to provide a significant technical and theoretical foundations for the somatic embryogenesis of slash pine.

Materials and methods

Materials

The following experiments used EC as the material. EC were induced from immature zygotic embryo. Slash pine seeds were collected in mid-July from Baiyunshan Forest Farm, Ji’an City, Jiangxi Province, China. The seeds were sterilized by soaking in 75% (v/v) alcohol for 5 min, then rinsed with sterile water. The immature zygotic embryos were then inoculated onto the induction medium and cultured in the dark at 23 ± 1℃ for 60 days. The induction, proliferation and maturation of EC were conducted using the medium previously optimized by our research group37. All experimental materials used were embryogenic callus with stable subculture for 70 days in good condition.

Methods

Culture conditions

Induction culture The induction medium is DCR basic medium37and supplemented with 2.0 mg/L 2, 4-D, 2.0 mg/L 6-BA, 2.0 mg/L NAA, 30 g/L sucrose, 500 mg/L CH, 500 mg/L L-glutamine, 250 mg/L MES and 4 g/L gellan gum. The pH is between 5.8 ~ 6.019,38.

Proliferation culture The proliferation medium is DCR basic medium supplemented with 30 g/L sucrose, 4 g/L gellan gum, 500 mg/L L-glutamine and 500 mg/L casein hydrolysate. The pH was maintained between 5.8 and 6.0. The EC was cultured in the dark at a temperature of 23 ± 1℃38. Each dish was inoculated with two 1 g clumps of healthy EC that had white, filamentous outgrowths. The weight of the EC was measured after 14 days, and all cultures were placed onto new medium every 14 days.

Maturation culture The EC was transferred to DCR proliferation medium with no hormone supplementation and cultured for 10 days. Subsequently, the EC was transferred to a maturation medium, 1 g EC was evenly distributed across four dishes, with 0.25 g allocated to each dish. The maturation medium composed of DCR basic medium supplemented with 10 mg/L ABA, 100 mg/L polyethylene glycol 8000, 20 g/L maltose, 4 g/L gellan gum, 500 mg/L L-glutamine, 500 mg/L casein hydrolysate and 250 mg/L 2-Morpholinoethanesulphonic acid37. The pH was maintained 6.0. The culture was maintained in the dark for 60 days at 25 ± 1 ℃.

Experimental design

Experiment 1: Optimization of EC proliferation culture conditions

Culture cycle of EC The EC induced in 2021 was used as the experimental material. The EC were cultured on a proliferation medium supplemented with 2.0 mg/L 2,4-D and 2.0 mg/L 6-BA, which is the hormone combination with the highest proliferation efficiency obtained from the previous laboratory research37. The durations respectively are 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, and 20 days. At each stage, the weight of the EC was measured to calculate the proliferation coefficient (Eq. 1) and the proliferation rate (Eq. 2). A single-factor experimental design was employed, with 1 g EC per dish, 6 dishes per treatment. The treatment was repeated three times.

.

Combination of PGRs concentrations A completely randomized block design was employed using 0.5, 1.0, or 1.5 mg/L of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 0.5, 1.0, or 1.5 mg/L of 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA), resulting in nine hormone concentration combinations. The fresh weight of the EC in each per dish was measured to calculate the EC proliferation coefficient (Eq. 1). Each treatment was replicated three times, and with 2 g EC per dish, 3 dishes per treatment.

Experiment 2: long-term maintenance and physiological and biochemical changes of EC

Effects of subculture duration on EC proliferation coefficient and the number of SE The EC induced in 2021 was used as the experimental material. The EC were cultured on a proliferation medium supplemented with 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D and 1.0 mg/L 6-BA. The EC proliferation coefficient (Eq. 1) was assessed on days 70, 140, 350, 700, and 980. Each treatment was replicated three times, and with 2 g EC per dish, three dishes per treatment.

After assessment, the EC after cultured 70, 140, 350, 700, and 980 days were cultured on a maturation medium respectively. After 60 days, the number of SE was assessed to calculate the number of SE induced by per gram EC (Eq. 3). Each treatment was replicated three times, with 0.25 g per dish, four dishes per treatment.

.

Measurement of physiological and biochemical indicators After assessment, on the 70th, 140th, 350th, 700th, and 980th day of culture, 5 g EC was taken and transferred to cryovials respectively, immediately submerged in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

Physiological indicators: Starch and soluble sugars contents were assessed using the sulfuric acid-anthrone method and measured at 620 nm with a spectrophotometer (GENESYS 18 UV-Visible Spectrophotometer, Thermo Scientific)38. Soluble proteins contents were quantified using the Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 method at 595 nm39.

Biochemical indicators: while catalase (CAT) activity was quantified using the Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 method using UV spectrophotometry at 240 nm39. The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (POD) were analyzed using kits from Nanjing JianCheng Bioengineering Institute. The SOD sample solution was prepared by homogenizing 0.1 g of sample in 400 µL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The POD sample solution was prepared by homogenizing 0.1 g of sample in 900 µL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant as retained for analysis.

Experiment 3: Maintenance of embryogenic capacity during long-term EC proliferation.

Combination of PGRs types and concentrations EC induced in 2023 was used as the experimental material. Based on the optimal combination of PGRs concentrations, this study explored the effects of six PGRs on EC proliferation: 2, 4-D, 6-BA, kinetin (KT), 2-(1-Naphthyl) acetic acid (NAA), abscisic acid (ABA), and brassinolide (BL) (Table 3). The weight of the EC was assessed after 14 days to calculate the proliferation coefficient (Eq. 1). Each treatment was replicated four times and with 2 g EC per dish, three dishes per treatment.

After assessment, the EC were cultured on a maturation medium. After 60 days, the number of SE was assessed to calculate the number of SE induced by EC per gram (Eq. 3). Each treatment was replicated three times, with 0.25 g per dish, four dishes per treatment.

Effects of subculture duration on EC proliferation coefficient and the number of SE EC were cultured on a proliferation medium supplemented with 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D, 1.0 mg/L 6-BA, and 1.0 mg/L NAA. The EC proliferation coefficient (Eq. 1) was assessed after subcultured for 112, 168, 224, 280, 336, and 392 days. Each treatment was replicated three times. 2 g EC per dish, three dishes per treatment.

After assessment, the EC were cultured on a maturation medium. After 60 days, the number of SE was assessed to calculate the number of SE induced by EC per gram (Eq. 3). Each treatment was replicated three times, with 0.25 g per dish, four dishes per treatment.

Additionally, the EC were stained with acid fuchsin (0.1%) and Evans blue (0.05%) double staining method, and observed under a MODEL ECLIPSE Ci-L microscope to assessed the structure of embryonal suspensor mass (ESM) after subcultured for 112, 280, 392 days.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with SPSS (v 25.0), followed by multiple comparisons using Duncan’s test. Path analysis was conducted to evaluate the effects of physiological indicators on proliferation coefficient. The model was developed using SPSS (v 25.0), and significant variables were identified through stepwise regression analysis, followed by the calculation of their path coefficients. Pearson’s correlation analysis, regression analysis, Dot-line plot, and histogram generation were performed using Origin Pro Learning Edition 2021. Figures modification using Adobe Illustrator. The data are expressed as mean values ± standard error.

Results

Culture cycle of EC

The experimental data indicate a significant positive correlation between proliferation coefficient and culture duration (Fig. 1a). Linear regression analysis produced the equation y = 0.511x − 2.161, with an R² value of 0.919, demonstrating a very high correlation between the two variables. As the culture duration increased, the proliferation coefficient also increased significantly. The fitted line closely matches the data trend, indicating that culture duration is a crucial factor affecting the proliferation coefficient.

As shown in the figure, the relationship between proliferation rate and culture duration follows a quadratic curve (Fig. 1b). The regression equation is y = −1.1784 + 0.38567x − 0.01526x², with a coefficient of determination R² = 0.400, indicating that culture duration accounts for 40% of the variation in proliferation rate. The results show that the proliferation rate peaks at around 12 days of culture, and then decreases gradually. Although some variability exists, the overall trend indicates an initial rise and subsequent decline in proliferation rate, highlighting the existence of an optimal culture duration.

The EC growth status is shown in Fig. 2. EC was transferred to the proliferation medium (Fig. 2a). EC exhibited obvious growth on day 4 (Fig. 2b), characterized by translucent, filamentous protrusions. Rapid growth occurred between days 4 and 12, with the proliferation rate peaking on day 12 before declining (Fig. 2c). Notably, EC began to turn brown on day 14 (Fig. 2d). Dense filamentous protrusions were visible on the surface of EC on day 16, but no significant proliferation was observed in EC during days 14 to 16 (Fig. 2e). The internal tissue turned brown, the surface filamentous protrusions became inactive, and the callus structure became loose on day 20 (Fig. 2f). Therefore, the optimal subculture cycle for EC was determined to be 14 days, during which the EC exhibited rapid growth, high early embryogenic activity, and maximum proliferation coefficient.

Effect of PGRs combinations on EC proliferation

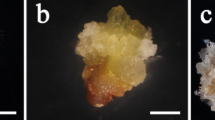

Different combinations of 2,4-D and 6-BA concentrations had significant effects on the proliferation coefficient (Table 1) (P = 0.000). The results showed that Treatment 5 (1.0 mg/L 2,4-D and 1.0 mg/L 6-BA) achieved the highest proliferation coefficient (7.65), which was significantly higher than the other treatments. This was followed by Treatment 6 (1.5 mg/L 2,4-D and 1.0 mg/L 6-BA) with a proliferation coefficient of 6.39. The lowest proliferation coefficient was observed in Treatment 7 (0.5 mg/L 2,4-D and 1.5 mg/L 6-BA) at 3.65. Overall, the combination of 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D and 1.0 mg/L 6-BA significantly promoted proliferation and had the best effect. At this optimal concentration combination, the callus displayed a white, translucent appearance with characteristic filamentous structures (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Effects of subculture duration on EC proliferation coefficient and the number of SE during long-term proliferation

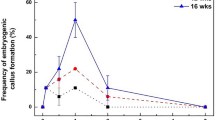

Subculture duration had no significant differences on EC proliferation coefficient (P = 0.121), despite the slight decrease in the EC proliferation coefficient with long-term subculture (Fig. 3b). The highest EC proliferation coefficient was observed at the 10th subculture, reaching 6.15. Although a decreasing trend in proliferation coefficient was noted after cultured 140 days, EC maintained a relatively high proliferation coefficient, achieving 4.72 at the 70th subculture. Subculture duration had a significant impact on the embryogenic capacity of EC (P = 0.000). The number of SE per gram of EC gradually decreased with long-time subculture, peaking at 19.67 during the 5th subculture (Fig. 3a). The results indicate that EC can proliferate stably for up to 980 days, while retaining its embryogenic capacity, under suitable conditions.

The physiological response of EC during long-term proliferation

Physiological indicators change in EC after 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, and 70th subculture is presented in Figs. 4 and 5. Significant differences were observed in stored substances (soluble sugars, starch, soluble proteins) content and redox substances (SOD, POD, CAT) activity in EC of different subculture times. The soluble protein and soluble sugars content of EC displayed a trend of initial increase followed by a decrease during long-term subculture. Both soluble proteins and soluble sugars content reached their peaks at the 10th subculture, with values of 6.85 mg/g and 30.28 mg/g, respectively. The soluble sugars content decreased to 26.8 mg/g at the 25th subculture and remained stable from the 25th to the 70th subculture. In contrast, soluble proteins content decreased to its lowest level of 5.49 mg/g at the 50th subculture. Starch content exhibited a significant decreasing trend throughout the long-term subculture process. It was highest at the 5th subculture, with a value of 0.14 mg/g, but decreased sharply at the 25th subculture and reached its lowest level of only 0.03 mg/g at the 50th subculture.

With increasing subculture times, CAT activity followed a trend of initial increase followed by a decrease, peaking at 1.39 U/min/mg FW at the 25th subculture. Both SOD and POD activities reached their lowest levels at the 10th subculture, with values of 7.94 U/mg FW and 254.33 U/g FW.

The correlation analysis between proliferation coefficient and physiological changes

Correlation analysis was conducted between the proliferation coefficient and physiological indices during the long-term proliferation of embryogenic callus (Fig. 6). The proliferation coefficient, starch content, and soluble sugar content were all negatively correlated with POD activity. In contrast, a positive correlation was identified between starch content and proliferation coefficient, as well as between soluble sugars content and starch content. Moreover, there was a significant positive correlation between soluble sugars content and proliferation coefficient(P < 0.01).These results indicate that the proliferation efficiency of embryogenic callus is mainly related to the content of storage substances (starch and soluble sugars) and the activity of redox substances (POD).

Correlation analysis between proliferation coefficient and physiological indicators of long-term proliferation of EC. Using Pearson correlation analysis, red represents a negative correlation, while blue represents a positive correlation. The closer the correlation coefficient is to 1, the stronger the correlation between the variables. * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01.

Path analysis of the effect of physiological indicators on the proliferation coefficient

A path analysis with multiple stepwise regression was performed (Table 2), by using proliferation coefficient as the dependent variable and six physiological indicators as independent variables. The multiple stepwise regression equation was y = −5.972 + 0.451 X1 −1.3 X2 (R²=0.996), where X1 represent soluble sugars content and X2 represent CAT activity. The direct path coefficients were ranked in descending order as follows: CAT activity > soluble sugars content > starch content > SOD activity > soluble proteins content > POD activity. Notably, the sum of the indirect path coefficients for starch content (1.06) exceeded that of the other physiological indicators (−0.94 to 0.61). The multiple stepwise regression equation and path analysis indicated that soluble sugars content and CAT activity were the most significant physiological indicators directly influencing proliferation coefficient, while starch content had the largest indirect effect on proliferation coefficient.

Optimization of PGRs types and concentrations

The above research results show that we obtained the maximum number of somatic embryos was only 19.67 per gram on the 70th day, and it dropped sharply in the 25th generation during long-term proliferation. Therefore, different concentrations of combined hormones were added to optimize the existing culture conditions.

Different hormone combinations had significant effects on both proliferation coefficient (P = 0.00) and number of SE (P = 0.000). As shown in Table 3, the proliferation coefficients of Treatment 1 (3.94) and Treatment 2 (2.70) were relatively high, but both resulted in low numbers of SE (5 and 9.5, respectively). Treatment 3 showed the lowest values for both proliferation coefficient (0.59) and somatic embryo number (0.25). Although Treatments 4 and 5 had lower proliferation coefficients (1.49 and 1.06) compared to Treatment 1, they produced substantially higher numbers of somatic embryos, reaching 143.25 and 111.75, respectively. In summary, Treatment 4 yielded the highest number of somatic embryos while maintaining an acceptable proliferation coefficient, making it the optimal combination of plant growth regulators.

Effect of subculture duration on proliferation coefficient and number of SE

Under optimal conditions, the proliferation coefficient (P = 0.934) and number of SE (P = 0.159) showed no significant changes over many subcultures (Table 4). After 392 days of culture, the EC exhibited stable proliferation, with a proliferation coefficient of 1.5 and an average yield of 117 SE per gram of EC. The highest proliferation coefficient, reaching 1.53 times the initial value, was observed at 224 days, accompanied by an average of 123.33 SE per gram of EC. Notably, the maximum SE yield of 143.33 per gram of EC was achieved at 280 days of proliferation culture. Furthermore, Additionally, there were no significant changes in ESM of EC during the long-term subculture process, and EC remained embryogenic at 392 days (Fig. 7). EC induced from immature zygotic embryos (Fig. S2a) was successfully differentiated into SE (Fig. S2c, S2d) after long-term proliferation culture (Fig. S2b), further developing cotyledons (Fig. S2e) and forming complete regenerated plantlets (Fig. S2f). This study has achieved stable long-term proliferation culture of EC in slash pine.

The filamentous outgrowths and the ESM structure of EC during long-term proliferation. a-c: The filamentous outgrowths of EC subcultured 112 days, 280 days, 392 days. (a): 112 days, (b): 280 days, (c): 392 days; The ESM structure of EC subcultured 112 days, 280 days, 392 days. (d): 112 days, (e): 280 days; (f): 392 days. All bars = 100 μm.

Discussion

Long-term proliferation of EC

It is difficult for EC to maintain stable proliferation and embryogenic potential during long-term proliferation. Previous studies on slash pine5 and Pinus koraiensis40,41,42 have shown that EC declines after six months of subculture. But the embryogenic lines of Larix × eurolepis43and Larix leptolepis44 remained stable after four and nine years of subculture, respectively. It indicates that in some species, EC can proliferate indefinitely under suitable conditions32,41,42. EC maintaining a relatively stable proliferation coefficient (4.05) for approximately three years(980 d), but the number of somatic embryos was low and significantly declined after 140 days. This may be due to the high proliferation rate of embryogenic callus, which could inhibit the development of somatic embryos45but more evidence is still needed to confirm this connection. To increase somatic embryo yield, this study further optimized the concentrations of plant hormones, using NAA supplementation to enhance somatic embryo production. Although the proliferation coefficient of embryogenic callus decreased, the callus was able to stably proliferate and efficiently differentiate over 392 days of continuous subculture.

The role of PGRs in EC proliferation and embryogenesis

Hormonal regulation plays a key role of EC proliferation and differentiation. The appropriate concentration, variety, and combination of plant growth regulators are crucial for SE and plant propagation46. Auxins and cytokinins are essential for maintaining optimal in vitro culture conditions45,47. Auxins like 2,4-D are critical for callus induction and proliferation, while cytokinins such as 6-BA promote cell division and differentiation48,49. The synergistic use of 2,4-D and 6-BA has been shown to enhance EC proliferation in various conifer species, such as Pinus koraiensis29 and Pinus nigra50. In this study, the effects of different PGR combinations on EC proliferation and embryogenic potential vary significantly. While the combination of 2,4-D and 6-BA achieved the highest proliferation coefficient, it resulted in a low number of SEs. It has been established that prolonged culture with 2,4-D reduces somatic embryo yield in sugarcane EC by increasing putrescine and spermidine levels, and interferes with the synthesis of key soluble proteins such as late embryogenesis abundant soluble proteins, chitinase, oleosin, and heat shock soluble protein51,52. These disruptions may negatively impact embryogenesis during long-term culture, but due to the fundamental differences in hormonal regulation between monocots and gymnosperms, further validation is needed in conifers.

In this study, the addition of other PGRs, such as ABA, BL, and NAA, resulted in a decline in proliferation coefficient, this may due to the disruption of hormonal balance, though the mechanisms remain unclear. NAA, commonly used to induce somatic embryogenesis, showed the highest SE yield in this study, with over 100 SEs per gram of EC. Similar results were observed in other species. For example, 3 mg/L NAA and 0.2 mg/L TDZ were most effective of Schisandra chinensis callus proliferation and metabolite synthesis53high NAA concentrations (10.0 mg/L) enhanced somatic embryogenesis in Ranunculus sceleratus54and 1 mg/L NAA and 0.25 mg/L 6-BA yielded the highest somatic embryo production at 166 embryos per gram in Pinus koraiensis28.

The optimal subculture cycle of EC

Regular subculturing prevents the accumulation of toxic metabolic byproducts and ensures a stable hormonal and nutritional environment, both of which are critical for sustained EC proliferation. The optimal subculture cycle for EC varies among different species. This study determined that the optimal subculture cycle for EC in slash pine is 14 days. The optimal subculture interval for Larix kaempferi55 is 20 days, while for Cinnamomum camphora56it ranges from 20 to 25 days. In contrast, the callus of Pinus koraiensis requires transfer to fresh medium every 13 to 15 days to maintain vigorous activity and achieve higher proliferation efficiency29.

Physiological response during long-term proliferation

The accumulation of starch, soluble sugars, and soluble proteins plays a critical role in EC proliferation and SE development51. Starch, as a primary energy source, supports cell division and differentiation57. Starch content exhibited a declining trend with successive subcultures, consistent with findings in sugarcane58.

Soluble proteins and soluble sugars, essential for metabolic energy and osmotic balance. Studies on Catharanthus roseus and sugarcane have demonstrated that EC contains higher levels of soluble proteins and soluble sugars compared to non-embryogenic callus58,59. Similarly, positive correlations between soluble proteins content and SE yield have been reported in Pinus thunbergia and pear cultivars33,60. In this study, soluble proteins and soluble sugars contents, along with proliferation coefficient, initially increased but subsequently declined with successive subcultures. This trend highlights the critical role of these storage compounds in supporting EC proliferation and SE development.

Antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD, CAT, and POD, regulate oxidative stress by regulating intracellular reactive oxygen species levels61. In this study, the results of correlation and path analyses between physiological indicators and proliferation coefficient indicate that the proliferation coefficient of EC is mainly related to the content of storage substances (starch and soluble sugars) and the activities of redox-related enzymes (POD and CAT). This result aligns with findings from studies on Pinus koraiensis38 and Pinus massoniana27. Similar findings also have been observed in other tree species, in Pinus pinaster62,63 the accumulation of storage soluble proteins during the mid-maturation phase of SE induced by EC serves as a reliable marker for high-quality somatic embryos. In Pinus massonian27and in sugarcane58non-embryogenic callus exhibits higher levels of polyphenols and polyphenol oxidase activity, whereas callus that has lost its embryogenic potential is characterized by reduced levels of storage substances (soluble proteins, soluble sugars, and starch) and increased activities of POD and CAT.

This study established a stable long-term proliferation system for slash pine EC, while our study focused on physiological and proliferation metrics, genetic stability analysis (e.g., karyotyping, SSR markers, or flow cytometry) would be essential for future validation.

Conclusion

This study established a stable long-term proliferation system for slash pine EC, with an optimal subculture interval of 14 days. The highest proliferation coefficient (7.65) was achieved using DCR medium supplemented with 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D and 1.0 mg/L 6-BA and embryogenic potential were maintained for up to three years. Under optimal conditions, additionally including 1.0 mg/L NAA, the maximum SE yield reached 143.25 per gram of EC. Regular medium replacement every 14 days ensured consistent proliferation and SE yield over 392 days of subculturing. Physiological analysis identified soluble sugars, starch contents, POD activity and CAT activity are key indicators of proliferation efficiency. This study initially overcame the difficulty of long-term subculture and loss of embryogenicity of embryonic callus in slash pine, achieving stable proliferation of embryonic callus (980 days) and maintenance of embryogenicity (352 days). And offering valuable insights into the physiological mechanisms underlying EC proliferation and embryogenic potential during somatic embryogenesis. This system has laid a technical foundation for the factory production of somatic embryogenesis in slash pine.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PGRs:

-

Plant growth regulators

- EC:

-

Embryogenic callus

- SE:

-

Somatic embryos

- ESM:

-

Embryonal suspensor mass

- PEM:

-

Pro-embryogenic mass

- DCR:

-

Douglas-fir Cotyledon Revised medium

- 2, 4-D:

-

2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

- 6-BA:

-

6-benzylaminopurine

- ABA:

-

Abscisic Acid

- NAA:

-

2-(1-Naphthyl) acetic acid

- KT:

-

Kinetin

- BL:

-

Brassinolide

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- POD:

-

Peroxidase

- CAT:

-

Catalase

References

Zhuang, W. Y., Zhang, Y. Y. & Zou, Y. X. Selection for high-resin yield of Slash pine and analysis of factors concerned. Acta Agric. Univ. Jiangxiensis. 29, 55–60 (2007).

Dong, J. X., Guo, H. J., Zhang, Z. Y., Wu, X. & Huang, P. Z. Dynamic change of pine resin resources in China in the last ten years—based on the data of continuous forest resource inventory. Sci. Silvae Sin. 52, 112–122 (2016).

Ding, X. et al. A transcriptome-based association study of growth, wood quality, and Oleoresin traits in a Slash pine breeding population. PLOS Genetics 18, e1010017 (2022).

Nielsen, U. B., Hansen, C. B., Hansen, U., Johansen, V. K. & Egertsdotter, U. Accumulated effects of factors determining plant development from somatic embryos of Abies nordmanniana and Abies Bornmuelleriana. Front Plant. Sci 13, 989484 (2022).

Hu, J. W. et al. Somatic embryogenesis and plantlet regeneration in Pinus elliottii and its hybrids. J. South. China Agric. Univ. 40, 107–115 (2019).

Yang, F., Xia, X. R., Ke, X., Ye, J. & Zhu, L. Somatic embryogenesis in Slash pine (Pinus Elliottii Engelm): improving initiation of embryogenic tissues and maturation of somatic embryos. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 143, 159–171 (2020).

Hakman, I., Fowke, L. C., Von Arnold, S. & Eriksson, T. The development of somatic embryos in tissue cultures initiated from immature embryos of Picea abies (Norway Spruce). Plant. Sci. 38, 53–59 (1985).

Jouini, N. et al. Somatic embryogenesis in Abies nebrodensis, an endangered Sicilian Fir. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 152, 393–404 (2023).

Gao, F. et al. Key techniques for somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration of Pinus koraiensis. Forests 11, 912 (2020).

Peng, C., Gao, F., Wang, H., Shen, H. & Yang, L. Optimization of maturation process for somatic embryo production and cryopreservation of embryogenic tissue in Pinus koraiensis. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 144, 185–194 (2021).

Chamberland, V. et al. Conventional versus genomic selection for white Spruce improvement: a comparison of costs and benefits of plantations on Quebec public lands. Tree Genet. Genomes. 16, 17 (2020).

Nagmani, R. & Bonga, J. M. Embryogenesis in subcultured callus of Larix decidua. Can. J. Res. 15, 1088–1091 (1985).

Arrillaga, I. et al. New approaches to optimize somatic embryogenesis in maritime pine. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 138 (2019).

Mohan Jain, S., Dong, N. & Newton, R. J. Somatic embryogenesis in Slash pine (Pinus elliottii) from immature embryos cultured in vitro. Plant. Sci. 65, 233–241 (1989).

Liao, Y. K. & Amerson, H. V. Slash pine (Pinus Elliottii Engelm.) somatic embryogenesis I. Initiation of embryogenic cultures from immature zygotic embryos. New. For. 10, 145–163 (1995).

Newton, R. J., Tang, W. spsampsps Jain, S. M. Slash pine (Pinus elliottii Engelm.). In Protocol for Somatic Embryogenesis in Woody Plants (eds. Jain, S. M. spsampsps Gupta, P. K.) 1–10 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2005). doi:10.1007/1-4020-2985-3_1.

Tang, W., Guo, Z. & Ouyang, F. Plantlet regeneration via somatic embryogenesis in Slash pine. J. Plant. Resour. Environ. 6, 8–11 (1997).

Cheng, Z. et al. Optimization of embryogenic callus induction conditions for somatic embryogenesis of Pinus elliottii. Acta Agric. Univ. Jiangxiensis. 43, 1054–1064 (2021).

Lelu-Walter, M. A. et al. Somatic embryogenesis for more effective breeding and deployment of improved varieties in Pinus spp.: bottlenecks and recent advances. In Somatic Embryogenesis: Fundamental Aspects and Applications (eds Loyola-Vargas, V., Ochoa-Alejo, N. et al.) 319–365 (Springer, 2016).

Fei, Q. et al. Somatic embryogenesis of Slash pine (Pinus Elliottii Engelm.): initiation, maturation, germination and mycorrhization of regenerated plantlets. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 157, 65 (2024).

Gao, F. et al. Optimization of key technologies for induction of embryogenic callus and maturation of somatic embryos in Korean pine (Pinus koraiensis). Forests 14, 850 (2023).

Chen, X. Long-term successional subculture dynamics and their effects on the proliferation efficiency, embryogenic potential, and genetic stability of embryogenic tissues in Larix principis-rupprechtii Mayr. Forests 15, 627 (2024).

Salaj, T., Matušíková, I., Fráterová, L., Piršelová, B. & Salaj, J. Regrowth of embryogenic tissues of Pinus nigra following cryopreservation. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 102, 41–48 (2010).

Cano, M. et al. Maritime pine Pinus pinaster Aiton. In Step Wise Protocols for Somatic Embryogenesis of Important Woody Plants (eds Jain, S., Gupta, P. et al.) 84 (Springer, 2018).

Breton, D. et al. Long-term subculture randomly affects morphology and subsequent maturation of early somatic embryos in maritime pine. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 87, 95–108 (2006).

Lineros, Y. et al. Effects of long-term subculture on maturation ability and plant conversion in Pinus radiata: using FT-IR spectroscopy to determine biomarkers of embryogenic tissue aging. Forests 14, 1446 (2023).

Xia, X. R. et al. Somatic embryogenesis of Masson pine (Pinus Massoniana): initiation, maturation and genetic stability analysis at SSR loci. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 145, 667–677 (2021).

Ren, Y., Nie, S., Peng, C., Yang, L. & Shen, H. Effects of hormone combinations, carbon source type and proliferation cycle on embryogenic callus proliferation of Pinus koraiensis. J. Northeast Univ. 38, 56–60 (2010).

Gao, F., Peng, C., Wang, H., Shen, H. & Yang, L. Selection of culture conditions for callus induction and proliferation by somatic embryogenesis of Pinus koraiensis. J. Res. 32, 483–491 (2021).

Nie, S. et al. Proper doses of Brassinolide enhance somatic embryogenesis in different competent Korean pine cell lines during embryogenic callus differentiation. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1330103 (2024).

Liu, G., Li, C. & Zhang, H. Screening of influence factors on maintenance and proliferation of embryogenic callus of Picea koraiensis. J. Northeast Univ. 38, 56–60 (2010).

Thorpe, T. A. Somatic embryogenesis: morphogenesis, physiology, biochemistry and molecular biology. Korean J. Plant. Tiss Cult. 27, 245–258 (2000).

Li, Y. et al. Physiological and transcriptomic analysis revealed the molecular mechanism of Pinus koraiensis responses to light. Int. J Mol. Sci. 23, 13608 (2022).

Hao, Z. et al. The plant peptide hormone phytosulfokine promotes somatic embryogenesis by maintaining redox homeostasis in Cunninghamia lanceolata. Plant. J. 113, 716–733 (2023).

Luo, Q. et al. Plant peptide hormone phytosulfokine promotes embryo development of mass in Pinus massoniana. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 158, 58 (2024).

Deng, Z. et al. Correlation between endogenous hormones and physiological and biochemical properties and somatic embryogenesis capacity of Pinus elliottii cell line. Guihaia 1–14. https://doi.org/10.11931/guihaia.gxzw202403025 (2024).

Cheng, Z. S. Study on somatic embryogenesis and physio-biochemical characteristics of Pinus elliottii. Dissertation, Jiangxi Agricultural University (2020).

Gupta, P. K. & Durzan, D. J. Shoot multiplication from mature trees of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana). Plant. Cell. Rep. 4, 177–179 (1985).

Peng, C., Gao, F., Wang, H., Shen, H. & Yang, L. Physiological and biochemical traits in Korean pine somatic embryogenesis. Forests 11, 577 (2020).

Liu, C. P. Physiological mechanism and differential protein of Fraxinus mandshurica somatic embryogenesis accompanied by explant browning. Dissertation, Northeast Forestry University (2009).

Liang, Y. et al. Morphological and endogenous phytohormone changes during long-term embryogenic cultures in Korean pine. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 151, 253–264 (2022).

Raemakers, C., Jacobsen, E. & Visser, R. Secondary somatic embryogenesis and applications in plant-breeding. Euphytica 81, 93–107 (1995).

Tretyakova, I. N. & Park, M. E. Collectible cell lines of Larix sibirica obtained by somatic embryogenesis and their ability to regenerate. Forests 14, 1920 (2023).

Pâques, L. E. et al. Larches (Larix sp.). In Forest Tree Breeding in Europe: Current State-of-the-Art and Perspectives (eds Pâques, L. E. et al.) 13–122 (Springer, 2013).

Wang, X. et al. High-efficiency somatic embryogenesis and morphohistology and histochemistry of somatic embryo development in Larix leptolepis Gordon. Stud. China. 9, 182–188 (2007).

Carneros, E. et al. Plant regeneration in stone pine (Pinus Pinea L.) by somatic embryogenesis. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 98, 165–178 (2009).

de Almeida, M., de Almeida, C. V., Graner, M. & Ebling Brondani, E. Fiori de Abreu-Tarazi, M. Pre-procambial cells are niches for pluripotent and totipotent stem-like cells for organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis in the Peach palm: a histological study. Plant. Cell. Rep. 31, 1495–1515 (2012).

Ikeuchi, M., Sugimoto, K. & Iwase, A. Mechanisms of induction and repression. Plant. Cell. 25, 3159–3173 (2013).

Tretyakova, I. N. et al. Content and immunohistochemical localization of hormones during in vitro somatic embryogenesis in long-term proliferating Larix sibirica cultures. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 136, 511–522 (2019).

Earnshaw, B. & Johnson, M. Control of wild Carrot somatic embryo development by antioxidants: A probable mode of action of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Plant. Physiol. 85, 273–276 (1987).

Salaj, T., Klubicová, K., Matusova, R. & Salaj, J. Somatic embryogenesis in selected conifer trees Pinus nigra Arn. and Abies hybrids. Front. Plant Sci. 10, (2019).

Reis, R. S., Vale, E. M., Sousa, K. R., Santa-Catarina, C. & Silveira, V. Pretreatment free of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid improves the differentiation of sugarcane somatic embryos by affecting the hormonal balance and the accumulation of reserves. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 145, 101–115 (2021).

Passamani, L. Z. et al. Long-term culture with 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid affects embryogenic competence in sugarcane callus via changes in starch, polyamine and protein profiles. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 140, 415–429 (2020).

Sun, D. et al. Optimization of culturing conditions for production of somatic embryos and lignins of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. Acta Physiol. Plant. 40, 166 (2018).

Xu, K. D. et al. NAA at a high concentration promotes efficient plant regeneration via direct somatic embryogenesis and SE-mediated transformation system in Ranunculus sceleratus. Sci. Rep. 9, 18321 (2019).

Lv, S. F., Zhang, S. G., Qi, L. W., Sun, X. M. & Wang, J. H. Somatic embryogenesis from immature embryos of Larix kaempferi. Sci. Silvae Sin. 41, 48–52 (2005).

Dai, X., Liu, X., Zhang, T., Li, J. & Zhou, C. Embryogenic callus induction and somatic embryogenesis from immature zygotic embryos of Cinnamomum Camphor. Acta Agric. Univ. Jiangxiensi. 41, 1120–1129 (2019).

Cangahuala-Inocente, G. C., Silveira, V., Caprestano, C. A., Floh, E. I. S. & Guerra, M. P. Dynamics of physiological and biochemical changes during somatic embryogenesis of Acca sellowiana. Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. -Plant. 50, 166–175 (2014).

Nieves, N. et al. Biochemical characterization of embryogenic and non-embryogenic calluse of sugarcane. Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. -Plant. 39, 343–345 (2003).

Fatima, S., Mujib, A. & Samaj, J. Anti-oxidant enzyme response during in vitro embryogenesis in Catharanthus roseus. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 86, 569–574 (2011).

Ameri, A., Davarynejad, G. H., Moshtaghi, N. & Tehranifar, A. The role of carbohydrates on the induction of somatic embryogenesis and the biochemical state of the embryogenic callus in Pyrus communis L. Cv. ‘Dar gazi’. Erwerbs-Obstbau 62, 411–419 (2020).

Blazquez, S. et al. Somatic embryogenesis in saffron (Crocus sativus L.): histological differentiation and implication of some components of the antioxidant enzymatic system. Plant. Cell. Tiss Organ. Cult. 97, 49–57 (2009).

Tereso, S., Zoglauer, K., Milhinhos, A., Miguel, C. & Oliveira, M. M. Zygotic and somatic embryo morphogenesis in Pinus pinaster: comparative histological and histochemical study. Tree Physiol. 27, 661–669 (2007).

Funding

This study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China during the 13th Five-Year Period (2017YFD0600502-5), the Jiangxi Forestry Science and Technology Innovation Project (202114), as well as the Science and Technology Research Foundation of the Education Department of Jiangxi Province (GJJ210401).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. supervised and revised the manuscript. Z.C. designed and conducted the experiments. J.X. and X.X. were involved in the acquisition and maintenance of experimental materials. Z.C. prepared the original draft. C.J. provided language assistance. M.Y. and M.L. proofread the article. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, Z., Jin, C., Yi, M. et al. Long term proliferation and physiological response of embryogenic callus in Slash pine (Pinus Elliottii Engelm). Sci Rep 15, 21327 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06436-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06436-5