Abstract

Freshwater mussels across Europe exhibit physiological and behavioural adaptations to survive winter conditions. Climate change projections, including more frequent extreme weather events, are expected to intensify pressures on these ecosystems. In this study, we tested the temperature-size hypothesis, which posits that larger body size in ectothermic organisms is an adaptation to colder climates. We predicted that Anodonta anatina populations in northern regions would have larger shells than those in central and southern regions. Additionally, we hypothesised that harsher winters in northern regions require mussels to maintain higher glycogen levels as an energy reserve. We also explored whether shell size varies between lowland and upland populations, following the temperature-size rule, and whether supercooling (SCP) occurs primarily in northern populations as a complementary survival strategy. Northern populations had the highest glycogen levels, reflecting adaptations to colder conditions. SCP was rare (2.5%) and observed predominantly in northern mussels, suggesting limited reliance on freeze avoidance. Instead, it is likely that mussels employ mixed strategies, such as metabolic reduction and burrowing, to withstand winter. These findings link shell size, glycogen levels, and SCP to specific survival strategies, providing new insights into the cold tolerance mechanisms of freshwater mussels and their potential vulnerability to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change projections indicate an increase in the frequency and intensity of storms, floods, heat waves, droughts, cyclones, and cold spells1,2. Freshwater ecosystems, being highly sensitive to variations in temperature and water availability, face particular challenges under these changes3,4. These challenges are compounded by significant alterations in the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of lakes and rivers driven by climatic warming. For instance, climate change strongly influences terrestrial catchments, where inputs to freshwater systems can be dampened or amplified by in-lake processes. This can lead to seemingly counter-intuitive responses, such as the acidification of streams but the alkalinisation of lakes in areas with limited base cation supplies5. Species inhabiting these environments, such as freshwater mussels of the order Unionida (hereafter referred to as “mussels”), are already experiencing significant declines due to habitat loss, pollution, and climate change5,6,7,8.

Mussels play a crucial role in freshwater and marine ecosystems, where they contribute to or provide many ecosystem services, such as nutrient cycling and storage, biofiltration, and food web modification9,10. However, they are particularly vulnerable to environmental fluctuations and extreme events11. As one of the fastest declining animal groups globally, mussels are especially vulnerable due to their long lifespans and limited mobility, which reduce their ability to escape adverse conditions7,12. Although freshwater habitats generally provide some thermal buffering, they are still susceptible to climate disturbances13. In particular, shallow streams, ponds, and the shores of larger water bodies are prone to freezing during winter months, exposing benthic organisms such as mussels to subzero temperatures13. Extreme cold can disrupt biological processes, leading to reduced activity or even cessation of essential functions3. These conditions can push temperatures beyond the thermal tolerances of some species, posing a serious threat to survival14. While high-temperature stress in bivalves has been extensively studied, knowledge about their responses to cold stress remains limited15,16.

The adaptations of bivalves to low temperatures may involve a combination of structural, physiological, and behavioural traits, such as the insulating properties of their shells, which may include specialised microstructures17; physiological mechanisms, such as changes in metabolic rate, modulation of oxygen demand, supercooling, or synthesis of cryoprotectants14,18,19,20 and body size adjustments in line with the temperature-size rule21,22,23. The temperature-size rule posits that ectothermic organisms tend to develop larger body sizes in colder climates, as lower temperatures slow metabolic rates, allowing for more efficient growth and resource use over longer periods23,24,25. Such adaptations may confer advantages in resource-limited, colder environments by promoting energy conservation and enhanced cold resistance23. Behavioural responses to low temperatures, such as burrowing into the sediment or moving to deeper water, also contribute to their survival26,27.

Cold-tolerance strategies can generally be categorised as either freeze avoidance or freeze tolerance14,20. Freeze avoidance involves mechanisms that prevent the formation of ice crystals in body fluids by lowering their freezing point, whereas freeze tolerance allows controlled ice formation in body tissues, thereby minimising cellular damage. However, these survival strategies remain poorly understood in large mussels, highlighting a significant gap in our knowledge of their cold-resistance mechanisms20. In species such as the duck mussel (Anodonta anatina), which inhabits diverse freshwater environments across the western Palearctic and Siberia, the ability to withstand cold temperatures likely varies in response to local climatic conditions27. This variation can manifest in several phenotypic traits, including shell size, physiological condition, and supercooling point (SCP). SCP measures how far below freezing temperatures body fluids can get before ice crystals form and is defined as the temperature at which ice crystals begin to develop. Mussels inhabiting colder environments are thought to have evolved or adapted physiological mechanisms, such as a lower SCP, to survive freezing conditions. Cold hardiness mechanisms are strongly linked to the metabolism of energy reserves, such as glycogen, which plays a key role in the synthesis of cryoprotectants, such as glycerol28,29,30,31. These cryoprotective substances help organisms survive freezing conditions by stabilising cellular structures and minimising damage caused by ice formation. The production and accumulation of cryoprotectants primarily depend on the availability of energy reserves and are critical for overwintering success32.

The objective of this study is to investigate key adaptive traits in freshwater mussels, using Anodonta anatina as a model organism. Focusing on body size, energetic condition (in terms of glycogen concentration), and SCP across environmental gradients—particularly latitude and altitude—this study examines how these traits vary within and among mussel populations. In this study, we propose several hypotheses to explain the observed variation in mussel traits across regions and environmental conditions. First, we hypothesise that environmental temperature influences mussel morphology and physiology in accordance with the temperature-size rule. Based on this, we predict that mussels in colder northern regions will have larger body sizes than those in central and southern Europe. We also hypothesise that seasonal climatic conditions shape energy storage strategies in mussels. Therefore, we predict that mussels from northern populations will exhibit higher glycogen concentrations, as longer and harsher winters in these regions likely require greater energy reserves for survival. In addition, we hypothesise that both latitude and altitude interact to affect mussel size. Accordingly, we predict that mussels from Northern and upland areas will generally have larger shells than those from South of Europe and lowland areas due to temperature rule size (latitude) and lower ambient temperatures (altitude). Finally, we hypothesise that low-temperature resistance mechanisms vary across climatic gradients. We predict that SCP will be most frequently observed in mussels from northern regions, where exposure to freezing conditions is more common.

By testing these hypotheses using A. anatina as a representative species, this study aims to shed light on the adaptive responses of mussels to different thermal environments. Our findings will contribute to a broader understanding of the ecological effects of temperature on species distributions, survival strategies, and the potential consequences of climate change in freshwater ecosystems.

Material and methods

Study sites and mussel collection

To examine mussel responses to variation in climatic conditions, individuals were collected from sites differing in latitude, altitude, and thermal regimes during the winter season, a period of maximum physiological preparation for overwintering (Fig. 1).

Sampling locations of Anodonta anatina across Europe, superimposed on the Köppen-Geiger climate classification map33.Red and green circles indicate the sites where mussels were collected. The map provides a visual representation of the climatic zones. The following climate types are included: Af—Tropical rainforest, Am—Tropical monsoon, Bwh—Hot desert, Bwk—Cold desert, Csa—Mediterranean hot summer, Csb—Mediterranean warm summer, Cwa—Subtropical with dry winters and hot summers, Cwb—Subtropical with dry winters and warm summers, Cfb—Temperate oceanic, Cfa—Temperate with hot summers, Dsa—Cold with dry summers and hot summers, Dsb—Cold with dry summers and warm summers, Dwa—Cold with dry winters and hot summers, Dwb—Cold with dry winters and warm summers, Dfa—Cold with no dry season and hot summers, Dfb—Cold with no dry season and warm summers, ET—Tundra. Map source: Adapted from Beck, H. E. et al. High-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger maps for 1901–2099 based on constrained CMIP6 projections. Sci. Data 10, 724 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02549-6. The map has been modified and simplified. The original data is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

In total, 322 A. anatina individuals were collected during the winter season of 2023/2024, with 150 individuals from Northern Europe (Scandinavia; Norway and Sweden), 98 from Central Europe (Poland), and 74 from Southern Europe (Portugal). Mussels were collected from lowland (3 in Northern, 3 in Central, and 2 in Southern Europe) and upland habitats (3 in Northern, 1 in Central, and 2 in Southern Europe). In Northern Europe, mussels were collected at 6 sites, exclusively in lakes; in Central Europe, they were found at 4 sites: 3 reservoirs and 1 river; and in Southern Europe, they were found at 4 sites, only in rivers. In all locations, mussels were collected manually. The sampling protocol required the collector to gather the first 30 individuals encountered, regardless of their size, to avoid any bias in sampling related to mussel size. However, the number of mussels collected per site varied, as it was not always possible to gather the required number in less abundant populations. In some cases, slight overcollections occurred due to collector error.

Climatic conditions

To verify that mussels collected from different regions and altitudes experience distinct climatic conditions, we compared air and water temperature regimes at all collection sites.

Climatic zones at mussel collection sites were visualised using high-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps 33. In Southern Europe, all sites were classified as “Csa” (hot-summer Mediterranean climate); in Central Europe, as “Cfb” (temperate oceanic climate); and in Northern Europe, the dominant class (5 out of 6 sites) was “Dfb” (warm-summer humid continental climate; Fig. 1).

Mean monthly air temperature at each site was obtained from ClimateData.org34,34, based on ECMWF data (0.1–0.25° resolution) collected between 1991 and 2021 and refreshed in May 2022. Mean monthly water temperatures were estimated using the Lake Model35over the period 1998–2009. The simulation incorporated site-specific meteorological and lake parameters, including wind components, air temperature, humidity, cloud cover, solar and thermal radiation, geographic coordinates, water depth (2 m), and assumed water transparency of 1 m.

To statistically test for differences in climatic conditions between regions, a repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare both air and water temperatures across months.

Additional details on the mussel collection sites, mean monthly air temperatures, and modelled water temperatures are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S1–S3).

Measurement of shell size and SCP

To assess variation in morphological and physiological traits relevant to cold adaptation, we measured shell size and SCP in all collected individuals. Each mussel was aged and measured for shell size upon collection. Shell length, width, and height were recorded using callipers. The age of individuals was determined by counting annual growth rings visible on the shell36. To minimise the risk of error in age determination, counting was performed on the right shell valve whenever possible. If growth rings were not clearly visible, the left valve was used instead.

To analyse variation in shell size across regions and habitats, we used a General Linear Model with region, habitat type, mussel age, and their interaction as predictor variables.

The SCP of each mussel was measured to assess cold tolerance following Sinclair et al.19. SCP was typically measured on 20–30 individuals per population to assess the distribution shape19. To obtain the SCP of mussel body fluids, a thermocouple (K-type, probe diameter 0.5 mm) was inserted into the posterior adductor muscle of each individual. The mussels were then placed in a deep freezer (Platilab 340 SV-3-STD; ALS Angelantoni Life Science deep freezer), with the temperature set to decrease from + 5 °C to − 20 °C at a constant rate of 1 °C/min, as recommended in previous SCP measurement studies19,20,37. The temperature decrease was continuously recorded, and the SCP was read off (with ± 0.1 °C accuracy) as the last temperature indication just before the peak (rebound) caused by the heat of the exothermic crystallisation reaction.

A freeze survival experiment was conducted at three sites in Central Europe. To assess post-freezing survival, after capturing the SCP, 8 mussels from each site were placed in water at 4 °C. They were then kept for another 7 days or until evidence of mortality was confirmed.

To explore potential physiological correlates of cold resistance, we used a linear regression to test for associations between SCP and both water temperature and glycogen concentration.

Glycogen concentration

To assess physiological condition and energy reserves in mussels from different climatic regions, glycogen concentration was measured in soft tissues. Each animal sample (whole tissue without the shell) was homogenised with 3–4 mL of distilled water using an IKA homogeniser (30 s pulse, 100% amplitude, 5–8 times). The homogenates were then centrifuged (10 min, 4 °C, 14,000 × g). The supernatants were used for further analysis. The ELISA Glycogen Assays (Sigma-Aldrich, No. MAK016 and MAK465, USA) were performed for the quantitative determination of glycogen. The Glycogen Assay Kit uses a single working reagent that integrates the enzymatic breakdown of glycogen with the measurement of glucose in a single step. The concentration of glycogen in the sample is proportional to the colour intensity of the reaction product, measured at 570 nm in flat-bottom clear 96-well plates.

Each 96-well plate had its own glycogen standard curve, run in duplicate. Additionally, a blank and a negative control were included for each plate. Samples were added to the plate in duplicate technical replicates for statistical purposes. Both glycogen assays were performed according to the ELISA manufacturers’ instructions, and the plates were then read at a wavelength of 570 nm using an Epoch 2 multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Differences in glycogen concentration were analysed using a two-way ANOVA with region and habitat type as fixed effects and their interaction.

Results

Climatic conditions

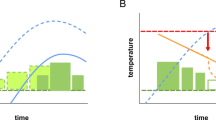

Repeated measures ANOVA showed that the highest mean yearly air temperature at collection sites was observed in Southern Europe (tmean = 14.8 °C; SD = 5.9; Fig. 2a). Whereas the mean yearly air temperature at collection sites in Central Europe (tmean = 9.1 °C; SD = 7.7; Fig. 2b) and Northern Europe (tmean = 5.5 °C; SD = 7.7; Fig. 2c) were lower, and the differences in mean yearly air temperature at collection sites among regions were significant (df = 2; F = 40.4; p < 0.0001). Also, the within effect (months) was significant (df = 11, F = 1690.1; p < 0.0001), as well as the interaction between region and within effect (months; df = 22; F = 21.6; p < 0.0001).

Mean monthly air temperatures (solid line) and range (minimum and maximum temperatures; dotted line) at collection sites in different climatic zones, located in Southern (a), Central (b), Northern (c) Europe34. Solid red horizontal lines indicate mean yearly temperature, red dotted horizontal lines indicate standard deviation of mean yearly temperature. (d) mean monthly water temperatures at collection sites modelled with FLake function. SE—Southern Europe, CE—Central Eurpe, NE—Northern Europe, Mer.—Mertola, Pat.—Pateira, VR—Villa Real, Mir.—Mirandela, Drz.—Drzewiczka, Zaj.—Zajączek, Zes.—Zesławice, Zap.—Zapadlisko, Hal.—Hallaskog, Bov.—Boverbu, Jar.—Jarenvatnet, Mid.—Midsjovannet.

Repeated measures ANOVA showed that modelled mean monthly water temperatures at collection sites also differed significantly among regions (Southern Europe: tmean = 17.3 °C, SD = 6.2.; Central Europe: tmean = 9.1 °C, SD = 7.6; Northern Europe: tmean = 7.3 °C, SD = 7.3; df = 2; F = 151.4; p < 0.0001), with significant influence of within effect (months; df = 11, F = 1709.9; p < 0.0001) and the interaction between region and within effect (months; df = 22; F = 23.8; p < 0.0001; Fig. 2D). Moreover, FLake model showed that the median number of weeks with ice covering the lake surface at collection sites was 15 in Northern Europe (range: 0–15), 2 in Central Europe (range: 0–3) whereas in Southern Europe ice cover on the lake surface did not occur at any of the collection sites.

Shell length

Descriptive statistics for mussel shell length are presented in Table 1. The General Linear Model showed that all analysed factors: region, habitat, mussel age, and the interaction between region and habitat, had significant influence on mussel shell length (Fig. 3a–c; detailed results in the Supplementary Materials, Table S1). Additionally, both age and the interaction between region and habitat had the highest influence on mussel shell length, whereas the influence of region and habitat on mussel shell length was much weaker (Supplementary Materials, Table S1). Mussels from Southern Europe were significantly longer than mussels from Central and Northern Europe, while no significant difference in length was observed between mussels from Central and Northern Europe (Fig. 3a). Also, mussels from Central and Southern Europe were significantly larger in lowland areas than in highland areas (Fig. 3b). However, the interaction between regions and habitat showed that mussels from Northern Europe were significantly longer in highland areas than in lowland areas. In contrast, mussels from Southern and Central Europe were significantly shorter in highland areas than in lowland areas (Fig. 3c). Together, these results suggest that both latitude and altitude jointly influence mussel shell size, with opposite altitudinal trends observed in Northern Europe compared to Central and Southern Europe.

The results of the General Linear Model showing the differences in mean shell length between regions (a), habitat types (b) and the interaction between region and habitat type (c). NE—Northern Europe, CECentral Europe, SE—Southern Europe, LL—lowlands, HL—highlands. Whiskers denote 95% confidence interval of the mean.

Frost resistance

The SCP was detected in only 8 individuals, representing 2.5% of all collected mussels: 7 individuals from Northern Europe (5%) and 1 individual from Central Europe (1%). No SCP was detected in individuals from Southern Europe (more details in the Supplementary Materials, Table S2). For those mussels with a measurable SCP (n = 8), linear regressions were performed to examine whether SCP was related to water temperature at the collection site or to glycogen concentration.

The higher the water temperature, the higher the SCP observed in mussels, but this relationship was not significant (linear regression; y = 0.75x − 1.7; p = 0.0828; Fig. 4a). Similarly, mussels with higher glycogen concentration in their tissues had higher SCP values, however, this relationship was not significant (linear regression; y = 0.556x − 1.9; p = 0.1534; Fig. 4b).

In Central Europe, post-SCP measurement survival varied by site. At the Zapadlisko site, 4 out of 8 individuals survived; at the Drzewiczka site, 5 out of 8 survived; and at the Zajączek site, only 1 out of 8 individuals survived the experiment (Table 2).

Glycogen concentration

Basic statistics of glycogen concentration in mussel tissues were presented in the Supplementary Materials (Table S3). Glycogen concentration significantly differed among regions (two-way ANOVA; df = 2; F = 194.2; p < 0.0001; Fig. 5), but not between habitats (two-way ANOVA; df = 1; F = 0.9; p = 0.3455; Fig. 5). The significant interaction between region and habitat (two-way ANOVA; df = 2; F = 3.4; p = 0.0361) showed that in Northern Europe, slightly higher glycogen concentrations were found in mussels from the lowland areas than mussels from the highland areas, while in Central and Southern Europe, the differences in glycogen concentrations in mussels from the lowland and highland areas were not significant (Fig. 5).

Discussion and conclusion

Contrary to our prediction on mussel size, our findings indicate that the largest mussels were found in Southern Europe, the warmest region. We argue that this result can be explained by the longer growing season and more stable environmental conditions in southern climates, which support growth throughout the year, increase resource availability, and provide energy for development38,39,40. Additionally, longer growing seasons may allow mussels to continue somatic growth even after reaching maturity, provided that environmental conditions are favourable and food is abundant. In mussel species such as Sinanodonta woodiana, warmer waters have been associated with continued growth after maturity and a more convex shell shape in females41,42. In contrast, colder regions are characterised by shorter growing seasons and limited resources, which can constrain growth by prioritizing energy investment towards survival rather than development43. The production of cryoprotectants and glycogen storage in colder climates may increase metabolic costs, reducing the energy available for shell growth. Furthermore, A. anatina does not exhibit a thermal compensation strategy, maintaining a consistently low energy requirement27. This physiological trait likely contributes to the smaller size observed in colder regions, despite the temperature-size rule.

In addition to latitudinal variation, we also hypothesised that mussels from upland areas would have larger shells than those from lowland areas due to lower temperatures in upland regions. Our results showed that mussels in Southern and Central Europe were larger in lowland areas, likely due to higher trophic levels in rivers and lakes, slower water flow, warmer waters, and abundant microorganisms that collectively support growth44,45,46,47,48. In contrast, upland areas in these regions may present harsher growth conditions, such as greater variability in water flow and lower nutrient levels. Furthermore, biotic interactions, such as competition or facilitation (e.g., aquatic vegetation providing shelter or increasing food availability), may also contribute to observed growth variations. These biotic interactions, combined with abiotic factors, highlight the complexity of ecological processes shaping mussel growth at local scales and emphasize the importance of considering both environmental and community-level factors7,8,10. In Northern Europe, lowland areas may experience more extreme hydrological conditions, such as stronger currents and sudden water level changes49,50, leading mussels to allocate more energy to survival than growth. In contrast, Northern European highlands, characterised by clean, cold, well-oxygenated waters, provided favourable growth conditions despite lower temperatures. Taken together, these findings suggest that both latitude and altitude shape shell growth in A. anatina, although their effects vary depending on the regional context.

Genetic differences among European mussel populations may also play a significant role in shaping their physiological responses to the environment. A. anatina is divided into distinct genetic clades, with Central and Northern populations sharing close genetic relationships, while the Iberian clade is more divergent51. Southern mussels may possess genotypes favouring faster growth, whereas Northern and Central populations may have evolved adaptations prioritising energy storage over intensive growth, enabling them to survive longer and colder winters. This pattern aligns with previous studies showing that animals at higher latitudes often exhibit metabolic compensation in low temperatures, leading to comparable metabolic rates across different environmental conditions52.

Phenotypic plasticity also plays a crucial role in local adaptation by allowing organisms to adjust to environmental variation without requiring genetic changes. Such plastic responses facilitate acclimation to new conditions and may contribute to long-term adaptation over generations53. For example, in A. anatina, plasticity may enable adjustments in growth rates, glycogen storage, and metabolic processes in response to climatic factors. However, while phenotypic plasticity provides immediate flexibility, long-term adaptation requires genetic changes that fine-tune physiological and morphological traits to local environments. Over time, plastic responses may become genetically encoded through genetic assimilation, as observed in other aquatic ectotherms with broad latitudinal distributions54. Further research on the genetic structuring of A. anatina populations could help disentangle the relative contributions of plasticity and genetic adaptation to environmental variation.

Another hypothesis proposed that mussels from northern populations would exhibit higher glycogen concentrations than those in Central and Southern Europe, reflecting adaptations to harsher winters requiring greater energy reserves. Our findings partially support this hypothesis, as glycogen levels showed a positive correlation with latitude. This trend likely reflects more stable year-round food availability at lower latitudes, reducing the need for glycogen reserves, combined with slower glycogen utilisation in colder waters44,45,55. Habitat type did not significantly affect glycogen levels, suggesting that temperature and food availability play a more critical role in glycogen accumulation than geographic elevation. Glycogen is primarily stored during spring and summer, when food availability is high, and is mainly used during gametogenesis56. Seasonal glycogen accumulation and depletion play a crucial role in mussel survival strategies, particularly in colder climates where metabolic demands fluctuate throughout the year.

As expected, mussel age had a strong influence on shell length, which is expected, as mussels exhibit indeterminate growth57, and older individuals are generally larger than younger ones.

The final hypothesis posited that SCP would be most frequently observed in mussels from northern regions as an adaptive strategy to survive low temperatures. Our findings indicate that SCP is rare in A. anatina, as only 2.5% of examined individuals exhibited this ability. This suggests that SCP is not a primary survival strategy for freshwater mussels. Instead, mussels in milder climates likely rely on reducing metabolism18 and burrowing into sediments for winter survival27,58. However, the presence of SCP capacity in a small percentage of individuals in colder regions suggests an adaptation to occasional low temperatures. The rarity of supercooling may be due to its high metabolic costs. Organisms employing this method often exhibit seasonal variation in SCP capacity, increasing it during colder periods20,59,60,61. Collecting mussels during the coldest part of winter, particularly after ice cover forms, could provide further insights into low-temperature adaptations in these populations.

Furthermore, variation in survival strategies suggests that A. anatina populations may employ a form of bet-hedging strategy, described in the context of adaptation to variable environmental conditions62. A small proportion of the population invests in SCP as an adaptive mechanism63, while the majority adopt less risky strategies, such as metabolic reduction and habitat selection. This "coin-flipping" strategy maximises survival chances across different environmental scenarios. Studying mussel responses to extreme cold could further elucidate their adaptive mechanisms and their relevance in the context of global climate change64.

Overall, our findings highlight the complexity of interactions between environmental conditions, physiological adaptations, and survival strategies in A. anatina. As global temperatures rise, longer growing seasons and warmer waters in Northern and Central Europe may lead to increased mussel sizes, potentially reducing current size differences between southern and northern populations. However, in Southern Europe, increasing water scarcity and more frequent droughts have already led to significant population declines64. Predictions indicate that rising air and water temperatures may exacerbate this trend, leading to further mortality and shifts in mussel distribution65,66.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in GitHub repository, at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13693199

References

Williams, G. et al. Come rain or shine: The combined effects of physical stresses on physiological and protein-level responses of an intertidal limpet in the monsoonal tropics. Funct. Ecol. 25, 101–110 (2011).

Weilnhammer, V. et al. Extreme weather events in Europe and their health consequences—A systematic review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 233, 113688 (2021).

Gosling, E. Bivalve molluscs: Biology, ecology and culture (John Wiley & Sons, 2008).

Döll, P. & Zhang, J. Impact of climate change on freshwater ecosystems: A global-scale analysis of ecologically relevant river flow alterations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 783–799 (2010).

Schindler, D. W. Widespread effects of climatic warming on freshwater ecosystems in North America. Hydrol. Process. 11, 1043–1067 (1997).

Woodward, G., Perkins, D. M. & Brown, L. E. Climate change and freshwater ecosystems: Impacts across multiple levels of organization. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 365, 2093–2106 (2010).

Lopes-Lima, M. et al. Conservation status of freshwater mussels in Europe: State of the art and future challenges. Biol. Rev. 92, 572–607 (2017).

Sousa, R. et al. A roadmap for the conservation of freshwater mussels in Europe. Conserv. Biol. 37, e13994 (2023).

Vaughn, C. C. Ecosystem services provided by freshwater mussels. Hydrobiologia 810, 15–27 (2018).

Zieritz, A. et al. A global synthesis of ecosystem services provided and disrupted by freshwater bivalve molluscs. Biol. Rev. 97, 1967–1998 (2022).

He, G. et al. Transcriptomic responses reveal impaired physiological performance of the pearl oyster following repeated exposure to marine heatwaves. Sci. Total Environ. 854, 158726 (2023).

Lopes-Lima, M. et al. Conservation of freshwater bivalves at the global scale: Diversity, threats and research needs. Hydrobiologia 810, 1–14 (2018).

Moss, B. et al. Climate change and the future of freshwater biodiversity in Europe: A primer for policy-makers. Fresh. Rev. 2, 103–130 (2009).

Ansart, A. & Vernon, P. Cold hardiness in molluscs. Acta Oecologica 24, 95–102 (2003).

Liu, Y., Wang, M., Wang, W., Fu, H. & Lu, C. Chilling damage to mangrove mollusk species by the 2008 cold event in Southern China. Ecosphere 7, e01312 (2016).

Masanja, F. et al. Surviving the cold: A review of the effects of cold spells on bivalves and mitigation measures. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1158649 (2023).

Wong, W. S. Y., Hauer, L., Cziko, P. A. & Meister, K. Cryofouling avoidance in the Antarctic scallop Adamussium colbecki. Commun. Biol. 5, 83 (2022).

Bayne, B. L. Physiological changes in Mytilus edulis L. induced by temperature and nutritive stress. J. Marine Biol. Associat. UK 53, 39–58 (1973).

Sinclair, B. J., Coello Alvarado, L. E. & Ferguson, L. V. An invitation to measure insect cold tolerance: Methods, approaches, and workflow. J. Therm. Biol. 53, 180–197 (2015).

Ansart, A., Guiller, A., Moine, O., Martin, M.-C. & Madec, L. Is cold hardiness size-constrained? A comparative approach in land snails. Evol. Ecol. 28, 471–493 (2014).

Macdonald, B. A. & Thompson, R. J. Intraspecific variation in growth and reproduction in latitudinally differentiated populations of the giant scallop Placopecten magellanicus (Gmelin). Biol. Bull. 175, 361–371 (1988).

Duchesne, J.-F. & Magnan, P. The use of climate classification parameters to investigate geographical variations in the life history traits of ectotherms, with special reference to the white sucker (Catostomus commersoni). Écoscience 4, 140–150 (1997).

Kozłowski, J., Czarnołęski, M. & Dańko, M. Can optimal resource allocation models explain why ectotherms grow larger in cold?1. Integr. Comp. Biol. 44, 480–493 (2004).

Atkinson, D. Temperature and organism size-a biological law for ectotherms?. Adv. Ecol. Res. 25, 1–58 (1994).

Atkinson, D. & Sibly, R. M. Why are organisms usually bigger in colder environments? Making sense of a life history puzzle. Trends Ecol. Evol. 12, 235–239 (1997).

Amyot, J. P. & Downing, J. A. Seasonal variation in vertical and horizontal movement of the freshwater bivalve Elliptio complanata (Mollusca: Unionidae). Freshw. Biol. 37, 345–354 (1997).

Lurman, G., Walter, J. & Hoppeler, H. H. Seasonal changes in the behaviour and respiration physiology of the freshwater duck mussel, Anodonta anatina. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 235–243 (2014).

Kim, Y. & Song, W. Effect of thermoperiod and photoperiod on cold tolerance of Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Environ. Entomol. 29, 868–873 (2000).

Atapour, M. & Moharramipour, S. Changes of cold hardiness, supercooling capacity, and major cryoprotectants in overwintering larvae of Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Environ. Entomol. 38, 260–265 (2009).

Atapour, M. & Moharramipour, S. Changes in supercooling point and glycogen reserves in overwintering and lab-reared samples of beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua (Lep.: Noctuidae) to determining of cold hardiness strategy. (2011).

Zheng, X.-L. et al. Cold-hardiness mechanisms in third instar larvae of Spodoptera exigua Hübner (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). African Entomology 22, 863–871 (2014).

Storey, K. B. & Storey, J. M. Freeze tolerant frogs: Cryoprotectants and tissue metabolism during freeze—Thaw cycles. Can. J. Zool. 64, 49–56 (1986).

Beck, H. E. et al. High-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger maps for 1901–2099 based on constrained CMIP6 projections. Sci Data 10, 724 (2023).

ClimateData, 2024. https://en.climate-data.org/. [Accessed 03 October 2024]

Lake Model Flake, 2009. https://www.cosmo-model.org/content/model/cosmo/misc/flake/default.htm. [Accessed 09 November 2024]

Haukioja, E. & Hakala, T. Measuring growth from shell rings in populations of Anodonta piscinalis (Pelecypoda, Unionidae). Ann. Zool. Fenn. 15, 60–65 (1978).

Salt, R. W. Principles of insect cold-hardiness. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 6, 55–74 (1961).

Blanchette, C. A., Helmuth, B. & Gaines, S. D. Spatial patterns of growth in the mussel, Mytilus californianus, across a major oceanographic and biogeographic boundary at Point Conception, California, USA. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 340, 126–148 (2007).

Schneider, K., Thiel, L. & Helmuth, B. Interactive effects of food availability and aerial body temperature on the survival of 2 intertidal Mytilus species. J. Therm. Biol 35, 161–166 (2010).

Page, H. M. & Hubbard, D. M. Temporal and spatial patterns of growth in mussels Mytilus edulis on an offshore platform: Relationships to water temperature and food availability. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 111, 159–179 (1987).

Labecka, A. M. & Domagala, J. Continuous reproduction of Sinanodonta woodiana (Lea, 1824) females: An invasive mussel species in a female-biased population. Hydrobiologia 810, 57–76 (2018).

Labecka, A. & Czarnoleski, M. Patterns of growth, brooding and offspring size in the invasive mussel Sinanodonta woodiana (Lea, 1834) (Bivalvia: Unionidae) from an anthropogenic heat island. Hydrobiologia 848(12), 3093–3113 (2021).

Jokela, J. & Mutikainen, P. Phenotypic plasticity and priority rules for energy allocation in a freshwater clam: A field experiment. Oecologia 104, 122–132 (1995).

Hatcher, A., Grant, J. & Schofield, B. Seasonal changes in the metabolism of cultured mussels (Mytilus edulis L.) from a Nova Scotian inlet: The effects of winter ice cover and nutritive stress. J. Exp. Marine Biol. Ecol. 217, 63–78 (1997).

Fearman, J.-A. et al. Energy storage and reproduction in mussels, Mytilus galloprovincialis the influence of diet quality. J. Shellfish Res. 28, 305–312 (2009).

Vannote, R. L., Cummins, K. W., Minshal, G. W., Sedell, J. R. & Cushing, C. E. The river continuum concept. Can. J. Fish. Aquatic Sci. 130–137 (1980).

Mouthon, J. Longitudinal organisation of the mollusc species in a theoretical French river. Hydrobiologia 390, 117–128 (1998).

Martello, A., Kotzian, C. & Erthal, F. The role of topography, river size and riverbed grain size on the preservation of riverine mollusk shells. J. Paleolimnol. 59, 1–19 (2018).

Nilsson, C. Rivers and streams. Acta Phytogeographica Suecica 84, 135–148 (1999).

Nilsson, C., Polvi, L. E. & Lind, L. Extreme events in streams and rivers in arctic and subarctic regions in an uncertain future. Freshw. Biol. 60, 2535–2546 (2015).

Lyubas, A. A. et al. Phylogeography and genetic diversity of duck mussel Anodonta anatina (Bivalvia: Unionidae) in Eurasia. Diversity 15, 260 (2023).

Sukhotin, A. A., Abele, D. & Pörtner, H. O. Ageing and metabolism of Mytilus edulis: Populations from various climate regimes. J. Shellfish Res. 25(3), 893–899 (2006).

Noble, D. W. A., Radersma, R. & Uller, T. Plastic responses to novel environments are biased towards phenotype dimensions with high additive genetic variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 13452–13461 (2019).

Johansson, F., Watts, P. C., Sniegula, S. & Berger, D. Natural selection mediated by seasonal time constraints increases the alignment between evolvability and developmental plasticity. Evolution 75, 464–475 (2021).

Makarieva, A. M., Gorshkov, V. G., Li, B.-L. & Chown, S. L. Size- and temperature-independence of minimum life-supporting metabolic rates. Funct. Ecol. 20, 83–96 (2006).

Thompson, R. J. The reproductive cycle and physiological ecology of the mussel Mytilus edulis in a subarctic, non-estuarine environment. Mar. Biol. 79, 277–288 (1984).

Haag, W. R. North American freshwater mussels: Natural history, ecology, and conservation (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

McMahon, R. F. & Wilson, J. G. Seasonal respiratory responses to temperature and hypoxia in relation to burrowing depth in three intertidal bivalves. J. Therm. Biol 6, 267–277 (1981).

Bale, J. S. Insect cold hardiness: Freezing and supercooling—An ecophysiological perspective. J. Insect Physiol. 33, 899–908 (1987).

Wang, J. & Wang, S. Variations of supercooling capacity in intertidal gastropods. Animals 13, 724 (2023).

Lipińska, A. M., Ćmiel, A. M., Olejniczak, P. & Gąsienica-Staszeczek, M. Constraints on habitat possibilities: Overwintering of a micro snail species facing climate change consequences in a harsh environment. Folia Biol. (Krakow) 72, 1–10 (2024).

Olofsson, H., Ripa, J. & Jonzén, N. Bet-hedging as an evolutionary game: The trade-off between egg size and number. Proc. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 276, 2963–2969 (2009).

Cooper, W. S. & Kaplan, R. H. Adaptive, “coin-flipping”: a decision-theoretic examination of natural selection for random individual variation. J. Theor. Biol. 94, 135–151 (1982).

Lopes-Lima, M. et al. The silent extinction of freshwater mussels in Portugal. Biol. Cons. 285, 110244 (2023).

Sousa, R. et al. Die-offs of the endangered pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera during an extreme drought. (2018) https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2945

Nogueira, J. G., Lopes-Lima, M., Varandas, S., Teixeira, A. & Sousa, R. Effects of an extreme drought on the endangered pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera: A before/after assessment. Hydrobiologia 848, 3003–3013 (2021).

Williams, G. A. et al. Come rain or shine: The combined effects of physical stresses on physiological and protein-level responses of an intertidal limpet in the monsoonal tropics (2011).

Acknowledgements

This publication is based upon work from COST Action CA18239: CONFREMU-Conservation of freshwater mussels: a pan-European approach, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). AML was supported by the National Science Centre, Poland Grant 2023/07/X/NZ9/00300 and partly by the statutory funds of the Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków. AMĆ was supported by the statutory funds of the Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków and partly by internal funding from INC PAS “Minigranty”. ML-L was funded by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia under contract (2020.03608.CEECIND). PI-F was supported by Grants4NCUStudents (90-SIDUB.6102.89.2023.G4NCUS7). JHM was supported by the Norwegian Research Council, through their basic funding for the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), and internal funding from NINA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AML: conceptualisation, field work, laboratory work, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; PA, PAI-F, AN, SC: laboratory work, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; AMĆ: shells size measurements, data analysis, visualisation of the data, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; MJG, SS, DH, ML-L, JHM, AT, SV: field work, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, MÖ: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lipińska, A.M., Adamski, P., Ćmiel, A.M. et al. Cold tolerance strategies of freshwater mussels across latitudes. Sci Rep 15, 22232 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06450-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06450-7