Abstract

This study assesses the diagnostic performance of six LLMs —GPT-4v, GPT-4o, Gemini 1.5 Pro, Gemini 1.5 Flash, Claude 3.0, and Claude 3.5—on complex neurology cases from JAMA Neurology and JAMA, focusing on their image interpretation abilities. We selected 56 radiology cases from JAMA Neurology and JAMA (from May 2015 to April 2024), rephrasing the text and reshuffling multiple-choice answer. Each LLM processed four input types: original quiz with images, rephrased text with images, rephrased text only, and images only. Model performance was compared with three neuroradiologists, and consistency was assessed across five repetitions using Fleiss’ kappa. In the image-only condition, LLMs answered six specific questions regarding modality, sequence, contrast, plane, anatomical, and pathologic locations, and their accuracy was evaluated. Claude 3.5 achieved the highest accuracy (80.4%) on original image and text inputs. The accuracy using the rephrased quiz text with image ranged from 62.5% (35/56) to 76.8% (43/56). The accuracy using the rephrased quiz text only ranged from 51.8% (29/56) to 76.8% (43/56). LLMs performed on par with first-year fellows (71.4% [40/56]) but surpassed junior faculty (51.8% [29/56]) and second-year fellows (48.2% [27/56]). All LLMs showed almost similar results across the five repetitions (0.860-1.000). In image-only tasks, LLM accuracy in identifying pathologic locations ranged from 21.5% (28/130) to 63.1% (82/130). LLMs exhibit strong diagnostic performance with clinical text, yet their ability to interpret complex radiologic images independently is limited. Further refinement in image analysis is essential for these models to integrate fully into radiologic workflows.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancement of large language models (LLMs) has greatly expanded their capabilities, moving beyond natural language processing tasks to specialized domains like healthcare and radiology1. Among these models, multimodal LLMs, such as OpenAI’s generative pretrained transformer 4 (GPT-4), Google’s Gemini, and Anthropic’s Claude, are capable of processing both textual and visual inputs and have demonstrated significant potential in interpreting complex language, contextual information, and even medical data, positioning them as valuable tools for diagnostic assistance and clinical decision-making2,3,4,5,6,7. There is an increasing interest in how these models can interpret medical images and offer clinical insights, particularly in radiology, where precise image analysis is critical3,8.

Despite these advances, current literature shows that while LLMs perform well on text-based medical cases, they often struggle with tasks requiring visual interpretation, such as identifying specific lesion locations or analyzing complex imaging findings3,9,10. In the field of neuroradiology imaging, comparisons of accuracy between LLMs and neuroradiologists have shown that LLMs did not demonstrate significantly superior diagnostic capabilities compared to humans3,11. These limitations raise concerns about their ability to replicate the nuanced reasoning that neuroradiologists apply when diagnosing from imaging data. Furthermore, much of the existing research evaluates LLMs using publicly available datasets, which poses a risk of data leakage and may result in an overestimation of the models’ diagnostic accuracy12.

In this study, we aim to address these limitations by evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of multimodal LLMs using independent, rephrased cases from JAMA Neurology and JAMA. By creating a test dataset that is independent of the models’ training data, we seek to minimize bias and provide a more accurate assessment of the LLMs’ ability to diagnose and interpret complex radiologic images. Additionally, we compare the performance of these models against that of neuroradiologists to evaluate whether LLMs can simulate the diagnostic reasoning required in clinical radiology practice. Furthermore, we sought to evaluate the models’ ability to interpret radiologic images and their underlying reasoning processes when analyzing visual data. Through these analysis, we aim to provide insights into the current capabilities of LLMs and identify areas where further improvements are needed to integrate these models effectively into radiologic workflows.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study did not include patient data; therefore, institutional review board approval was waived.

Case selection from JAMA neurology and JAMA clinical challenges and rephrased quizzes generation

Clinical challenges quizzes from JAMA Neurology and JAMA (https://jamanetwork.com/collections/44038/clinical-challeng) was searched in July 5th 2024, and only the neurology cases with radiologic images (CT, MRI, angiography and nuclear medicine) were included in this study. Consequently, 56 cases from May 2015 to April 2024 were studied.

To avoid the dependence of the LLMs on the training data as the study investigating the ability of the LLMs to generate an autonomous reasonable clinical diagnoses12,13, the quizzes text were rephrased using different words or word orders without changing their original meanings, and the multiple choices were rearranged in randomly generated by GPT-4o (Supplementary material). The rephrased quizzes were reviewed by an experienced diagnostic neuroradiologist (C.H.S. with experience of 13 years in radiology) to ensure relevance and consistency. A flow chat of the study design is depicted in Fig. 1. The rephrased quiz text and the sources of the questions have been summarized in the Supplementary Table.

Using LLM for answering quizzes

The study implemented six LLMs: GPT-4 Turbo with Vision (GPT-4v) (version gpt-4 turbo-2024-04-09) and GPT-4 Omni (GPT-4o) (version gpt-4o-2024-05-13) by OpenAI, Gemini 1.5 Pro and Gemini 1.5 Flash by Google DeepMind, Claude 3.0 (version claude-3-opus 20240229) and Claude 3.5 (version claude-3-5-sonnet 20240620) by Anthropic. The six LLMs were accessed between July 27th and 31st, 2024. All LLMs were assessed using three different temperatures—a parameter that affects the randomness and diversity of LLMs’ response, as higher temperatures lead to generate more diverse responses, whereas lower temperatures make more deterministic outputs; temperature 0 (T0), 0.5 (T0.5), and 1 (T1)12,13. In addition, the quizzes answering processed five time each in different session to each LLMs to assess repeatability of the responses, and out of the five responses, the initial attempt was chosen for the analysis14.

In this study four input methods were processed by the six LLMs including: (1) the original quizzes, (2) rephrased quizzes, (3) only rephrased text quizzes, and (4) only image quizzes. The LLMs were challenged to solve the original quizzes at first, and the rephrased quizzes in a separate session to study the impact of the dependence of the LLMs on the training data. In addition, to evaluate the impact of the radiologic images on the LLMs attempts, they were asked to solve the rephrased quizzes without images. Prompts were instructing to answer the clinical challenge quizzes by choosing the most correct answer of the multiple choices. Prompts also clarified that the quizzes were not for medical purpose to avoid the refusal of the LLMs to respond. The prompt engineering and running LLMs were conducted by a neuroscientist (W.H.S.). as follows:

Assignment: You are a board-certified radiologist and you are tasked with solving a quiz on a special medical case from common diseases to rare diseases. Patients’ clinical information and imaging data will be provided for analysis; however, the availability of the patient’s basic demographic details (age, gender, symptoms) is not guaranteed. The purpose of this assignment is not to provide medical advice or diagnosis. This is a purely educational scenario designed for virtual learning situations, aimed at facilitating analysis and educational discussions. You need to answer the question provided by selecting the option with the highest possibility from the multiple choices listed below.

You need to answer the question provided by selecting the option with the highest possibility from the multiple choices listed below. Please select the correct answer by typing the letter that corresponds to one of the provided options. Each option is labeled with a letter (A, B, C, D, etc.) for your reference.

-

Question: {symptom_text}

-

Output Format (JSON).

-

{{

-

“answer”: “Enter the number of the option you believe is correct”,

-

“reason”: “Explain why you think this option is the correct answer”.

-

}}

Additionally, the LLMs were challenged by the image only quizzes and were asked to answer six questions: (1) what is the type of the medical imaging? (2) What is the specific imaging sequence? (3) Is the study contrast enhanced? (4) What is the image plane? (5) What part of the body is imaged? (6) Where is the location of the abnormal findings?, The LLMs temperature was adjusted on temperature 1 (T1) when they were tasked to answer these questions3.

Evaluations

To evaluate the accuracy of human readers, three board-certified, neuroradiologists were involved in answering the quizzes. One junior faculty neuroradiologist (P.S.S.), one second-year neuroradiology fellow (J.S.K.), and one first-year neuroradiology fellow (A.A.), answered the quizzes using the same rephrased texts with images provided to LLMs. All human readers were unaware that the cases were from the clinical challenges quizzes from JAMA Neurology and JAMA. They were otherwise thoroughly informed on the quiz-answering guidelines: (1) Prohibited to search the internet or textbooks while answering cases. (2) Completed the session without breaks. (3) Time taken to answer each case was recorded. After completing the quiz, it was confirmed that none of the human readers had previous experience clinical challenges quizzes from JAMA Neurology and JAMA. A relatively experienced neuroradiologist not involved in answering the cases (C.H.S.) checked whether the answers of the human readers and LLMs were correct.

Statistical analysis

Accuracy of the LLMs then analyzed by selecting the initial attempt, which considered representative among the five repetitions. For each quiz case, accuracy was defined as the proportion of cases in which the LLM’s first response selected the correct multiple-choice option. The ground truth answer for each quiz was based on the official answer provided by the JAMA Clinical Challenge. For image-only tasks, in which LLMs were asked to answer six predefined questions (e.g., imaging modality, sequence, contrast, etc.), correctness was adjudicated by a senior neuroradiologist (C.H.S.) with extensive experience in both radiologic interpretation and prior LLM assessments. Each of the six answers per case was independently evaluated as correct or incorrect.

First, comparing the accuracy of the attempt using different temperature was done across the first three input methods (the original quizzes, rephrased quizzes and only rephrased text quizzes) using generalized estimating equations to account for observations within subjects. Additionally, differences in accuracy across brain disease sub-sections (genetic disease, autoimmune/inflammation/infection, metabolic disease, neurodegeneration, tumor, and vascular disease) for each model were analyzed using the Chi-squared test.

Second, accuracy of four LLMs (GPT-4v, GPT-4o, Gemini 1.5 Pro, and Claude 3.5) and three human readers was compared using generalized estimating equations with the exchangeable working correlation structure. In addition, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted if the overall comparison showed statistical significance and LLMs with the highest accuracy using the rephrased text with images were compared with the results of the human readers. A p-value of < 0.017 was considered statistically significant after applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (comparing with three human readers and the highest accuracy LLM) in the post-hoc analysis.

Third, the generated responses after five repetitions were assessed and compared to evaluate stochasticity of LLMs using Fleiss’ kappa statistics. A κ-value > 0.8 indicated almost perfect agreement, whereas 0.61–0.80, 0.41–0.60, 0.21–0.40, < 0.20 indicated substantial, moderate, fair, and poor agreement, respectively15.

Fourth, comparing the accuracy of LLMs for image only analysis were conducted using generalized estimating equations. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 27.0 for Windows; IBM Corp.) and R version 4.4.0 (https://www.r-project.org).

Results

Clinical challenges quizzes from JAMA neurology and JAMA

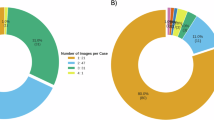

A total of 56 clinical challenge quiz neurology cases were included in this study, all of which contain radiological images of various regions: brain (n = 34), spine (n = 4), head and neck (n = 4), and multiple areas (n = 14). The sub-sections within the brain region were as follows: genetic disease (6/34), autoimmune/inflammation/infection (8/34), metabolic disease (5/34), neurodegeneration (5/34), tumor (9/34), and vascular disease (1/34). The images were obtained using different modalities, including MRI (n = 36), CT (n = 2), both MRI and CT (n = 4), MRI and radiographs (n = 1), MRI and angiography (n = 1), MRI and clinical photos (n = 10), MRI and pathological slides (n = 1), and nuclear medicine studies (n = 1).

Accuracy of LLMs according to the input types

At first, the accuracy of the six LLMs has been compared after using three input types: (1) Original quiz text with image, (2) Rephrased quiz text with image, (3) Rephrased quiz text only. The accuracy range using the original quiz text with image from 51.8% (29/56) to 80.4% (45/56). The highest accuracy of 80.4% was the result of Claude 3.5 (T0, T0.5 and T1). The accuracy using the rephrased quiz text with image ranged from 62.5% (35/56) to 76.8% (43/56). The highest accuracy of 76.8% was the result of Claude 3.5 (T0, T0.5 and T1). There was no significant difference in the accuracy among different temperature settings in each LLM. For all LLM models and all temperature settings, there were no significant differences in accuracy across the brain disease sub-sections for the original quizzes, rephrased quizzes, and only rephrased text quizzes.

Then, the accuracy between using rephrased quiz text with image and rephrased quiz text only was compared. The accuracy using the rephrased quiz text only ranged from 51.8% (29/56) to 76.8% (43/56), and the highest accuracy 76.8% was achieved by Claude 3.5 (T0, T0.5 and T1). There was no statistically significant in the accuracy using the rephrased quiz text only, except for Gemini Flash. The accuracy of LLMs according to input types and temperatures is shown in Table 1. An example of inaccurate interpretation following rephrasing is shown in Fig. 2.

An example of inaccurate interpretation following rephrasing by Claude 3.5 with temperature 1. This radiologic quiz is created based on a JAMA neurology case23, featuring an adolescent boy presenting with cognitive and behavioral changes. The correct diagnosis is “Germinoma”. In the rephrased version, descriptions of the imaging findings were somewhat condensed, resulting in Claude 3.5 providing an incorrect answer. The lesion location is indicated by yellow highlights, and the imaging findings are marked by green highlights for clarity.

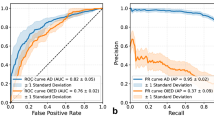

Accuracy of LLMs and human readers for rephrased texts with images

The accuracy of the three human readers was compared with the LLMs that achieved the highest accuracy using rephrased texts with images, Claude 3.5, GPT-4v, GPT-4o and Gemini 1.5 Pro, using the generalized estimating equations. Accuracy of the junior faculty 51.8% (29/56), was lower than the accuracy of the LLMs (P < .001 after Bonferroni correction) which is statistically significant. The accuracy of the second year clinical fellow 48.2% (27/56), was lower than the accuracy of the LLMs (P < .001 after Bonferroni correction) which is statistically significant. However, the accuracy of the first year clinical fellow was 71.4% (40/56), which was not significantly different from that of the LLMs. The comparison among the accuracy of all LLMs and human readers was also of no statistical significance (P = .017 after Bonferroni correction). The accuracy of LLMs and human readers for rephrased texts with images is shown in Fig. 3; Table 2.

Stochasticity of LLMs

Stochasticity was assessed by the use of Fleiss’ kappa (Table 3). All LLMs showed almost similar results across the five repetitions (GPT-4v: 0.919–0.990, GPT-4o: 0.860–0.976, Gemini 1.5 Pro: 0.891–0.985, Gemini Flash: 0.950-1.000, Claude 3.0: 0.905-1.000, Claude 3.5: 0.990-1.000). The highest κ-value was 1.000, achieved by Gemini Flash (T0 and 0.5), Claude 3.0 (T0) and Claude 3.5 (T0). The κ-values increased as temperature settings decreased in all LLMs.

Accuracy of LLMs for image only analysis

The accuracy of the six LLMs using the image only quizzes was compared regarding six different questions about: (1) the modality, (2) the sequence, (3) the contrast administration, (4) the image plane, (5) the anatomical location, and (6) the pathologic location, using the generalized estimating equations. The accuracy of LLMs for image only analysis is shown in Fig. 4; Table 4. The accuracy range regarding the modality was from 80.0% (104/130) to 96.2% (125/130). The highest accuracy of 96.2% was achieved by Claude 3.5 (T1). The accuracy range regarding the sequence was from 23.8% (31/130) to 81.5% (106/130) and the highest accuracy of 81.5% was achieved by GPT-4v (T1). In addition, the accuracy range regarding the contrast administration was from 45.4% (59/130) to 90.8% (118/130), with highest accuracy of 90.8% was achieved by GPT-4v (T1). The accuracy range regarding the image plane was from 50.8% (66/130) to 98.5% (128/130), with highest accuracy of 98.5% achieved by GPT-4v (T1). In addition, the accuracy range regarding the anatomical location was from 53.1% (69/130) to 97.7% (127/130), with the highest accuracy of 97.7% was achieved by Claude 3.5 (T1). The accuracy range regarding the pathologic location was from 21.5% (28/130) to 63.1% (82/130), and the highest accuracy of 63.1% was achieved by Claude 3.5 (T1),

Discussion

In our study, we assessed the diagnostic accuracy of LLMs across a range of neurology cases from JAMA Neurology and JAMA, involving radiologic images, and compared their performance to that of neuroradiologists. Our findings demonstrate that the best-performing LLMs, particularly Claude 3.5, achieved relatively high accuracy (up to 80.4%) when provided with original image and text inputs. Notably, the LLMs demonstrated similar accuracy when provided with either rephrased text with images or rephrased text only, indicating that the models were capable of solving the clinical challenges based primarily on text inputs. When compared with neuroradiologists, the LLMs performed at a similar level as first-year clinical fellow, while outperforming junior faculty and second-year clinical fellow in some cases. While LLMs like Claude 3.5 and GPT-4v achieved high accuracy in identifying imaging modalities and anatomical locations, their ability to interpret pathologic locations from images alone was less satisfactory.

Previous studies have evaluated LLMs using open-source cases from widely accessible medical journals, which may lead to data leakage and overestimate the models’ performance due to familiarity with the training data3,5,12,16. To mitigate this, we employed rephrased text versions of the JAMA Neurology and JAMA clinical challenges. By rephrasing the quiz texts and reshuffling multiple-choice answers, we ensured the independence of our test data, making our evaluation of the models more robust and unbiased. This adds significant value to our study, as it truly challenges the LLMs’ ability to generate clinical diagnoses without relying on pre-exposed material. To further assess the effect of modifying textual inputs, we compared model accuracy using both the original quiz texts and their rephrased counterparts. Except for Gemini Flash, there was no statistically significant difference in accuracy between the original and rephrased inputs for any of the LLMs, which may reflect variations in processing strategies across different model architectures. These findings suggest that LLMs possess capabilities beyond simple keyword matching, demonstrating an ability to identify and integrate essential elements of clinical scenarios, thereby enhancing their credibility as tools capable of adapting to the diverse and variable clinical descriptions encountered across institutions and clinicians in real-world practice17.

Additionally, by utilizing clinical challenge quizzes from JAMA neurology and JAMA, which are peer-reviewed and specifically designed for education and professional development, our study further increased the complexity of the LLMs’ tasks. These quizzes closely mimic real-world clinical scenarios, providing not just imaging data but also critical clinical information such as patient demographics, symptoms, and clinical history. This setup tests the LLMs’ interpretative abilities, ensuring that their performance is based on their capacity to synthesize and analyze complex clinical inputs, rather than relying on pre-trained responses.

A notable aspect of our study was the assessment of the stochasticity of LLMs across multiple attempts, which demonstrated consistent and robust results, particularly in models like Claude 3.5 and GPT-4v (Fleiss’ kappa score: Claude 3.5 = 0.990-1.000 and GPT-4v = 0.919–0.990). The high Fleiss’ kappa scores in repeated trials indicate that these LLMs could maintain a stable performance across different sessions, which suggests that they could be reliable tools for clinical decision-making. This consistency is crucial when considering the integration of AI models into healthcare workflows, where reproducibility of decisions is paramount18,19.

Interestingly, while the LLMs demonstrated strong performance with rephrased text-only inputs, this strength may actually highlight a limitation in their radiologic interpretative abilities. The fact that these models performed well without the aid of imaging suggests they are heavily reliant on detailed clinical information rather than their ability to analyze images20. This reliance on text alone, while beneficial for processing clinical information, raises concerns about their ability to independently interpret complex imaging findings—a key skill required for radiologists. Notably, LLMs demonstrated high accuracy for imaging modality (80.0-96.2%) and anatomical location identification (53.1–97.7%), but showed substantially lower performance for pathologic location identification (21.5–63.1%). This disparity suggests that while vision-enabled LLMs are capable of basic image interpretation and normal anatomical structure recognition, they have marked limitations in precise spatial localization of subtle pathologic changes21. These results align with previous studies showing that while LLMs have improved in understanding radiologic imaging, they still lack the nuanced interpretative skills required for precise diagnoses and decision-making that human radiologists possess10,22. While current LLMs demonstrate strengths in interpreting text-based clinical information, they may benefit from further development in precise localization tasks requiring complex visual reasoning. Given the importance of accurate pathologic localization for treatment planning and prognosis prediction in neuroradiology practice, this limitation warrants further investigation and improvement before broader clinical implementation.

There are several limitations to our study. First, while the human evaluators were neuroradiologists with expertise in interpreting radiologic images, their relative lack of extensive clinical experience compared to general neurologists or other clinicians may have influenced their performance, especially given the detailed clinical information provided in the JAMA case challenges. Future studies should incorporate a broader range of clinical participants with varying levels of expertise and from diverse practice backgrounds to better contextualize LLM performance and assess its potential across real-world diagnostic settings. Second, although we created rephrased quizzes to reduce the chance of data leakage from pre-trained models, we did not assess the impact of different prompting styles or rephrased inputs on the LLMs’ reasoning processes in greater detail, and the images themselves were not modified, which introduces a residual risk of potential data leakage within the core design of the study. However, the LLMs demonstrated diagnostic performance comparable to first-year neuroradiology fellows and only selectively outperformed more experienced readers, which suggests that their responses likely reflect genuine clinical reasoning rather than simple recall of training data. If data leakage were the primary factor, we would have expected them to consistently surpass all human evaluators. Third, the multiple-choice format, modeled after JAMA quizzes, may have inadvertently inflated the perceived performance of LLMs by narrowing the diagnostic options and reducing the complexity of decision-making, potentially overestimating their true diagnostic capabilities in real-world scenarios. Future studies could address this limitation by incorporating naturalistic narrative cases or longitudinal scenarios to better reflect the complexity of real clinical workflows. Fourth, our findings reflect the capabilities of LLMs available at the time of the study; however, with the emergence of newer and potentially more advanced models, such as OpenAI’s “o1 pro,” future assessments may yield different results, underscoring the need for ongoing re-evaluation as the technology evolves. Future research should focus on developing and continuously benchmarking integrated reasoning systems capable of processing multimodal inputs to improve diagnostic accuracy in complex clinical scenarios. Fifth, the structured format of image-only questions (six predefined elements) may have limited the assessment of models’ ability to perform integrated visual reasoning in more nuanced clinical scenarios. Lastly, due to the nature of the quizzes, which included a relatively high proportion of rare diseases compared to more common conditions encountered in general practice, neuroradiologists who were unable to consult the internet or textbooks may have been at a disadvantage. Furthremore, this selection may not fully reflect the spectrum of complexity, ambiguity, and case variability encountered in real-world radiologic practice. This also limits the generalizability of the findings to more frequently encountered disease groups.

Conclusion

While LLMs demonstrated strong performance in text-based tasks, their ability to independently interpret radiologic images, particularly in identifying pathologic locations in neuroradiology, remains limited. Further improvements, particularly in the interpretative analysis of imaging, are needed for these models to become more fully integrated into clinical workflows.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study were sourced from “Clinical Challenge” articles published in JAMA and JAMA Neurology. Because these journals are not open access, the original quiz materials and figures are not publicly available. However, we independently generated rephrased quiz texts to minimize data leakage. The rephrased quiz texts and the sources of the questions are summarized in the Supplementary Table. Researchers with appropriate institutional access to the journals may refer to the original articles.

Abbreviations

- GPT-4:

-

Generative pretrained transformer 4

- GPT-4o:

-

GPT-4 omni

- GPT-4v:

-

GPT-4 turbo with vision

- LLM:

-

Large language model

References

Bhayana, R., Krishna, S. & Bleakney, R. R. Performance of ChatGPT on a radiology board-style examination: Insights into current strengths and limitations. Radiology 307, e230582. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.230582 (2023).

Kurokawa, R. et al. Diagnostic performances of Claude 3 opus and Claude 3.5 sonnet from patient history and key images in radiology’s diagnosis please cases. Jpn J. Radiol. 42, 1399–1402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-024-01634-z (2024).

Suh, P. S. et al. Comparing diagnostic accuracy of radiologists versus GPT-4V and gemini pro vision using image inputs from diagnosis please cases. Radiology 312, e240273. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.240273 (2024).

Akinci, D. et al. Large language models in radiology: Fundamentals, applications, ethical considerations, risks, and future directions. Diagn. Interv Radiol. 30, 80–90. https://doi.org/10.4274/dir.2023.232417 (2024).

Ueda, D. et al. Diagnostic performance of ChatGPT from patient history and imaging findings on the diagnosis please quizzes. Radiology 308, e231040 (2023).

Mondal, H. et al. Assessing the capability of large Language model chatbots in generating plain Language summaries. Cureus 17 (2025).

Sarangi, P. K. et al. Assessing ChatGPT’s proficiency in simplifying radiological reports for healthcare professionals and patients. Cureus 15 (2023).

Sarangi, P. K. et al. Assessing the capability of chatgpt, Google bard, and Microsoft Bing in solving radiology case vignettes. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 34, 276–282 (2024).

Kung, T. H. et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: pOtential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLOS Digit. Health 2, e0000198. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000198 (2023).

Yan, Z. et al. Multimodal ChatGPT for medical applications: an experimental study of GPT-4V. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.19061 (2023).

Nazario-Johnson, L., Zaki, H. A. & Tung, G. A. Use of large language models to predict neuroimaging. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 20, 1004–1009 (2023).

Park, S. H., Suh, C. H., Lee, J. H., Kahn, C. E. Jr & Moy, L. Minimum reporting items for clear evaluation of accuracy reports of large Language models in healthcare (MI-CLEAR-LLM). Korean J. Radiol. 25, 865 (2024).

Park, S. H. & Suh, C. H. Reporting guidelines for artificial intelligence studies in healthcare (for both conventional and large language models): What’s new in 2024. Korean J. Radiol. 25, 687 (2024).

Suh, C. H., Yi, J., Shim, W. H. & Heo, H. Insufficient transparency in stochasticity reporting in large Language model studies for medical applications in leading medical journals. Korean J. Radiol. 25, 1029 (2024).

Landis, J. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics (1977).

Li, D. et al. Comparing GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 accuracy and drift in radiology diagnosis please cases. Radiology 310, e232411 (2024).

Goh, E. et al. Large language model influence on diagnostic reasoning: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 7, e2440969–e2440969 (2024).

Wu, S. H. et al. Collaborative enhancement of consistency and accuracy in US diagnosis of thyroid nodules using large language models. Radiology 310, e232255 (2024).

Kim, S., Lee, C. & Kim, S. Large language models: A guide for radiologists. Korean J. Radiol. 25, 126 (2024).

Waisberg, E. et al. GPT-4 and medical image analysis: strengths, weaknesses and future directions. J. Med. Artif. Intell. 6 (2023).

Sarangi, P. K., Datta, S., Panda, B. B., Panda, S. & Mondal, H. Evaluating ChatGPT-4’s performance in identifying radiological anatomy in FRCR part 1 examination questions. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 35, 287–294 (2025).

Wu, C. et al. Can gpt-4v (ision) serve medical applications? Case studies on gpt-4v for multimodal medical diagnosis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.09909 (2023).

Lou, X., Tian, C. & Ma, L. Evolution of unilateral basal ganglia lesion over 16 months. JAMA Neurol. 75, 376–377 (2018).

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant Number: RS-2018-KH049509).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by A.A., J.S.K., C.H.S., and P.S.S. The first draft of the manuscript was written by A.A. and J.S.K. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. A.A. and J.S.K. contributed equally to this work as co-first authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study did not include patient data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Albaqshi, A., Ko, J.S., Suh, C.H. et al. Evaluating diagnostic accuracy of large language models in neuroradiology cases using image inputs from JAMA neurology and JAMA clinical challenges. Sci Rep 15, 43027 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06458-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06458-z