Abstract

Amitraz is a formamidine acaricide applied to hives to manage Varroa destructor, an ectoparasite of honey bees. As a high affinity octopaminergic agonist it is potentially neuroactive. Previous studies have described various effects or no effects of exposure to amitraz on honey bee sucrose sensitivity, learning, and memory but have not factored in age at exposure as a variable. This study conducted gustatory response assays, learning trials, and memory recall trials to examine the effects of amitraz on honey bee behavior. Topical application of acetone, the solvent vehicle, decreased sucrose sensitivity in newly emerged and foraging age honey bees; addition of amitraz to the acetone restored sucrose sensitivity to levels shown by untreated controls. Amitraz produced subtle effects on learning and memory in intermediate age and foraging age bees, whereas acetone treatment alone hindered performance. These results are consistent with prior demonstrations that stimulation of octopamine receptors increases sensitivity to sucrose but do not allow us to assess if amitraz facilitates olfactory learning. The effects of acetone were surprising, given its prior use as a neutral solvent in insect behavioral and toxicological studies. The results support use of alternative solvent vehicles in future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ectoparasitic mite Varroa destructor is a widespread pest of managed honey bee colonies of Apis mellifera, the Western honey bee. Adult mites puncture the cuticle of brood and adults to feed on hemolymph and the fat body, an insect organ that combines the functions of vertebrate liver and adipose tissue1. In addition to this direct harm, mites vector viruses including deformed wing virus, black queen cell virus, and acute bee paralysis virus2,3,4. The presence of mites in honey bee colonies is associated with a decline in colony health and nutritional status, a condition referred to as varroosis5. Varroosis is regarded as a contributor to global declines in managed honey bee populations6,7.

In response to mite infestations, many beekeepers treat their colonies with acaracides7,8. A popular choice is amitraz, a formamidine sold under the registered trademark of Apivar®. Apivar® is applied in the form of ethylene vinyl acetate strips infused with amitraz and laid across the top bars in hives. Apivar® is currently effective in reducing infestations, but evolving resistance in mite populations may eventually limit its usefulness7,9.

Amitraz functions as a potent acaricide primarily because it binds octopamine receptors. Octopamine is a biogenic amine that functions as a neurotransmitter and neuromodulator in the brain and peripheral nervous systems of arthropods10. Amitraz depolarizes arthropod skeletal muscle fibers11,12. Mites exposed to amitraz experience tremors and convulsions that lead to detachment from the honey bee host and, ultimately, death. Receptors for octopamine are members of the G-protein coupled receptor family of integral membrane proteins13. A recent study compared a key octopamine receptor of honey bees, AmOctβ2R, with its Varroa destructor counterpart, VdOctβ2R14. The honey bee receptor was found to be less sensitive to amitraz than the mite receptor because of amino acid substitutions in the ligand-binding domain unique to honey bees and bumblebees. This difference accounts for the low toxicity of amitraz to honey bees relative to its toxicity to mites but leaves open questions of possible sublethal effects that may diminish health and pollination efficacy.

A comprehensive survey of the impact of various xenobiotics on honey bees determined that published studies have rarely incorporated age at exposure as a factor, have rarely validated laboratory studies with field studies, and have almost never included amitraz15. Knowledge of potential sublethal impacts of amitraz on honey bees is consequently sparse relative to knowledge of the sublethal effects of other xenobiotics, such as neonicotinoids and fipronil. One possible reason for the smaller number of studies of amitraz may be that this compound is viewed by beekeepers as a helpful medicine rather than a harmful toxin.

In a study described by its authors as a “worst case” field exposure scenario, amitraz was dissolved in acetone and applied at field-relevant concentrations to the dorsal thorax of honey bees16. A laboratory-based behavioral assay, the proboscis extension response (PER), was used to test recall of a learned association of an odor and a food reward 1 h and 2 h after training (short-term memory). The performance of amitraz-exposed bees was not different from that of acetone-only controls. By contrast, topical application of amitraz was found to have a negative effect on recall of a learned association between an odor and a food reward 48 h after training (long-term memory)17. In a third study, honey bees were fed sublethal doses of amitraz dissolved in a sucrose solution. PER was used to test recall of a learned association at 1 h and 24 h, as well as the ability to detect low concentrations of sucrose. Exposures to a combination of amitraz and thiacloprid, a neonicotinoid pesticide, reduced recall and sucrose sensitivity18. In a study with non-behavioral endpoints, amitraz was shown to alter heart rate and decrease survival of honey bees infected with flock house virus19.

In light of these contradictory reports, the present study re-examined potential sublethal effects of amitraz on honey bees using PER for sucrose sensitivity and olfactory association learning assays. These tasks were selected because they represent components of normal foraging behavior. Once a honey bee lands on a flower, she senses nectar availability with gustatory receptors on her antennae, tarsae, and mouthparts20. Once the bee discerns the sweetness of nectar, she associates the scent of the flower with nectar availability, an association that can be retained for hours to days21,22. Because octopamine has been demonstrated to be required for associative olfactory learning in honey bees and other insects23,24,25,26, we considered the possibility of positive (performance-enhancing) as well negative (performance-degrading) effects of exposure to amitraz. An additional goal of this study was to ask if age at the time of amitraz exposure was related to impact.

Methods

Honey bees

Honey bees (Apis mellifera) were collected from a single colony installed in a standard Langstroth hive in the Wake Forest University Apiary over a collection period of May – September 2022. The Russian queen (open-air mated with Italian drones) was purchased from Mann Lake Bee and Ag Supply (Hackensack, MN, USA). No signs of altered queen behavior or swarming were observed over the collection period, indicating that the honey bees tested were likely all Russian-Italian hybrids.

Brood frames with capped brood were inspected at the hive to assess pupal age based on eye pigmentation27. Frames with emerging adults were transferred to a laboratory incubator (33˚C). Newly emerged bees were tested on the same day or given a small dot of enamel paint (Testor Corporation, Rockford, IL, USA) on the dorsal thorax and returned to the hive. Marked bees of known age were collected as needed from the hive entrance (foraging age bees, 18 + days since marking) or from the top frames of the hive (intermediate age bees, 11–16 days of age and, occasionally, foraging age bees if an insufficient number of foragers was available at the hive entrance on a test day).

Ethical review and approval were not required for this study in full accord with local legislation and institutional requirements.

Preparation and application of amitraz

Amitraz (98.8% purity, CAS: 33089-61-1; Chem Service, Inc., West Chester, PA, USA) and acetone (99+% purity; CAS: 67-64-1; Fisher Scientific Co. L.L.C., Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) were used to treat experimental subjects. Two µl of amitraz dissolved in acetone (0.335 µl/mL) was topically applied to the dorsal abdomen of harnessed bees using a 10 µl glass syringe (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). This dose was selected to simulate topical exposure of bees to amitraz in managed hives. Treatments were given 2 h prior to behavioral testing, simulating the short-term aftermath of the introduction of amitraz to a hive by a beekeeper. Two controls were used: acetone application alone, or no application of any substance (untreated).

Harnessing and food deprivation prior to testing

Honey bees were chilled briefly on ice for ease of handling, then harnessed as previously described in plastic straws28,29. A window was cut into the straws prior to harnessing to allow applications of treatments to the dorsal abdomen.

A honey bee must have both the ability and the motivation to extend her proboscis to produce data. A period of food deprivation was used as needed to produce roughly equivalent motivational states across different test days30,31,32. After harnessing, all subjects were touched on an antenna with a wooden applicator stick (Puritan Medical Products; Guilford, ME, USA) soaked in a 50% sucrose solution (w/v; fine granulated white sugar dissolved in deionized water) and, if proboscis extension was observed (i.e., motivation was present), the subjects proceeded immediately to treatment followed by a 2 h period of food deprivation prior to testing. If fewer than half of the subjects in a group responded to 50% sucrose with a proboscis extension, an additional food deprivation period of 2 h was used prior to treatment to standardize motivation across subjects. As a result, the period of food deprivation was varied (to ensure roughly equivalent motivation), but the time between treatment and testing was always 2 h. Harnessed bees were held in an incubator (28˚C) prior to testing.

Gustatory response assays of sucrose sensitivity

PER in response to detection of sugar by gustatory receptors is an unlearned reflex displayed by many insects33. PER has been widely used in gustatory response assays to assess honey bee sucrose response thresholds34. The sucrose solutions are touched to the antennae so that the solution is not consumed during the assay. Newly emerged and foraging age bees were used in tests of sucrose sensitivity. Newly emerged bees were chosen because of their reported lower sensitivity to sucrose compared with foragers, allowing assessment of potential subtle positive effects of amitraz treatments; foraging age bees were chosen because they are reportedly more sensitive to sucrose than younger bees, allowing assessment of potential subtle negative effects of amitraz treatments35. Eight concentrations of sucrose solution (w/v) were prepared in deionized water: 0.3%, 1%, 3%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30%, and 40%.

At the start of a test session, each subject was touched on an antenna with a wooden applicator stick soaked in deionized water as a control for thirst. Bees that responded with PER to water were allowed to drink until satiated to eliminate thirst as a confound. Next, a 50% sucrose solution was applied to an antenna to re-check motivation. Bees that did not respond to 50% sucrose at this time were not included in further assays or data analyses. Bees were then exposed again to water. Only bees that responded with PER to 50% sucrose but not to water at this time were included in testing and subsequent data analyses.

All bees were tested with each sucrose solution in order of increasing concentration. Water was applied to an antenna of each bee between sucrose solutions. Two min were allowed to elapse after water application. A score of 0 to 8, indicating the number of solutions to which the bee had responded, was assigned to each bee tested. This score is the Gustatory Response Score (GRS)35. All bees included in the statistical analyses did not respond to water before, during, and after testing, and all responded to the 50% sucrose solution before and after testing.

To aid in interpretation of the observed effects of amitraz treatment on sucrose sensitivity, a pilot study was performed on a separate set of subjects pretreated with injection of an octopamine blocker, epinastine, prior to treatment with amitraz. Because the test methods were similar but not identical to those used in this study, these data are not reported in this manuscript but are presented as Supplementary Information (S1).

Learning and recall assays

Intermediate age bees (11–16 days old) were collected from the top frames and foraging age (18 + days old) bees were collected from the top frames and hive entrance. Subjects were harnessed and a wooden applicator stick soaked in water was touched to the antennae; if bees responded with PER, they were allowed to drink water until satiated. All bees were then stimulated with 50% sucrose. If more than half of the group responded, bees were treated and housed in the incubator for 2 h prior to testing. If fewer than half of the group responded to the initial motivation check, an additional food deprivation period of 2 h prior to treatment was used to balance motivation as described in the preceding section. Harnessed bees were held in an incubator at 28˚C prior to training. Training began 2 h after treatment. At the start of training, bees were placed immediately outside of a laboratory fume hood (SafeAire Laboratory Fume Hoods; Hamilton Laboratory Solutions, L.L.C.; Manitowoc, WI, USA) and checked again for motivation by touching the antennae with 50% sucrose. Bees that did not respond at this time (immediately before training) were not tested.

Peppermint extract (McCormick & Company, Inc.; Hunt Valley, MD, USA) was used as the conditioned stimulus (CS). Peppermint was chosen because it is uncommon in the local area, so that any subjects with natural foraging experience would be unlikely to have had prior contact with this odorant. Ten µl of extract was applied to a semicircle of filter paper (Whatman™ No. 4, 9 cm; Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA), which was then placed inside a 5-ml syringe. A blank control was prepared using filter paper treated with 10 µl distilled deionized water. Syringes were placed in a clamp held in a lab stand positioned in the fume hood with the tip of the syringe 1 cm in front of the antennae of a bee positioned for testing.

Training sessions consisted of 5 presentations of the CS and 5 presentations of the blank. Five conditioning trials were presented in a random sequence interspersed with the 5 blank trials for a total of 10 trials per bee. The interval between trials was 10 min. In control trials, the syringe plunger of the control (blank) syringe was slowly pushed for 5 s with no application of sucrose to the antennae. In conditioning trials, bees were exposed to the odorant by slowly pushing the plunger of the scented syringe for 5 s. During the last 3 s of odorant presentation, a wooden applicator soaked in 50% sucrose solution (the unconditioned stimulus, or US) was applied to an antenna, overlapping the CS. The bee was allowed to feed for 3 s after presentation of the sucrose solution. After all pairings of the CS-US and blank trials were completed, bees remained in position for 25 s to weaken any inadvertent associations between contextual cues and the predictive link with the US33. Anticipatory (learned) responses prior to the presentation of the US were recorded. No data were gathered during blank trials, as those trials were used to control for contextual learning, including possible responses to mechanical stimulations of slight air movements. After the training trials, bees were returned to the 28˚C incubator until recall testing.

Trained bees were held in the incubator for 1–48 h (bees held for 48 h were fed to satiety every 6–8 h with 50% sucrose solution). At the appropriate time, a motivation check (application of 50% sucrose to an antenna) was performed. Non-responders were not included in recall trials. During the trials, bees were placed inside the fume hood in the same configuration as the learning trials and exposed for 5 s to the odorant without presentation of sucrose solution and observed for PER. To reduce the possibility of an extinction effect, no group used for a 1 h recall trial was tested again at 48 h.

Data analysis and visualization

Mean ranks of GRS and LRS were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis tests with Dunn’s tests for multiple pairwise comparisons conducted post hoc. Pairwise comparisons of bees from different age groups were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Chi-Square tests for independence were used to compare the proportion of bees extending their proboscis at each sucrose concentration during sucrose sensitivity testing and olfactory association trials. Data were analyzed and visualized in GraphPad Prism Version 9 (San Diego, GraphPad Software, Inc., Dotmatics, 2023). Learning data and tables were organized using R, Version 4.2.236. P-values were compared to an alpha value of α = 0.05.

Results

Sucrose sensitivity

GRS was used to compare the sucrose sensitivity of newly emerged and forager age worker honey bees (Fig. 1). There were three groups in each age category: (1) treated with amitraz dissolved in acetone (Amitraz/acetone), (2) treated with acetone (Acetone only), or (3) treated with neither Amitraz/acetone nor Acetone only (No treatment). In both newly emerged and forager age bees, there was an overall effect of treatment group on the mean ranks of GRS (newly emerged: Kruskal-Wallis statistic = 50.09, P < 0.0001; forager age: Kruskal-Wallis statistic = 41.28, P < 0.0001). Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that newly emerged Amitraz/acetone bees had a higher mean GRS than those in the Acetone only group (Dunn’s test, P < 0.0001). In addition, newly emerged No treatment bees had a higher mean GRS rank than those in the Acetone only group (Dunn’s test, P < 0.0001; Fig. 1). There was no difference between the Amitraz/acetone and No treatment newly emerged groups. Amitraz/acetone foraging age bees had a higher mean rank of GRS than those in the Acetone only group (Dunn’s test, P < 0.0001; n = 70); the No treatment group did not differ from either the Amitraz/acetone or Acetone only groups.

Despite the similar means of the scores shown in Fig. 1, pairwise comparisons between the newly emerged and foraging age cohorts based on rank revealed differential impacts of treatment by age. The mean GRS rank of foraging age bees treated with Amitraz/acetone (65.73) was significantly higher than the mean GRS rank (55.51) of newly emerged bees treated with Amitraz/acetone (Mann-Whitney U = 1513, P = 0.0389). The mean GRS rank of Acetone only foraging age bees (56.6) was significantly higher than that of newly emerged bees (42.24) given the same treatment (Mann-Whitney U = 833.0, P = 0.0194). No difference, however, was detected between the mean GRS ranks of No treatment foraging age bees and newly emerged bees (18.23 and 23.63, respectively; Mann-Whitney U = 146.0, P = 0.1601), indicating that age alone was not a direct predictor of sucrose sensitivity in our testing scenario.

Lower concentrations of sucrose solution showcased the effects of treatment on PER (Fig. 2A). In newly emerged bees, the Amitraz/acetone group had significantly higher proportions of PER responders than those treated with Acetone only at 0.3% (χ2 = 32.08, P < 0.0001), 1% (χ2 = 40.44, P < 0.0001), 3% (χ2 = 25.07, P < 0.0001), and 10% (χ2 = 14.92, P = 0.0001). No differences were detected at the four highest sucrose concentrations across treatment groups. Strikingly, no differences were detected between the Amitraz/acetone-treated group and the No treatment groups at any concentration.

Effects of treatments on proportions of PER responders across sucrose concentrations in newly emerged bees (A) and foraging age bees (B). Chi-Square tests, P < 0.05 for all differences. Asterisk = difference between Amitraz/acetone and Acetone only; diamond = difference between Amitraz/acetone and No treatment; star = difference between Acetone only and No treatment.

Foraging age bees in the Amitraz/acetone group had a higher proportion of PER responses than those treated with Acetone only at sucrose concentrations of 0.3% (χ2 = 46.72, P < 0.0001), 1% (χ2 = 31.65, P < 0.0001), 3% (χ2 = 13.36, P = 0.0003), and 10% (χ2 = 5.228, P = 0.0222). Those treated with Amitraz/acetone also had a higher proportion than No treatment bees at 0.3% concentration (χ2 = 11.7, P = 0.0006). A difference was detected between Acetone only bees and No treatment bees at 1% sucrose (χ2 = 4.629, P = 0.0314), with no differences detected at the four highest sucrose concentrations across treatment groups (Fig. 2B).

Olfactory association learning and recall

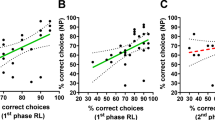

Each bee trained received five trials pairing the odorant with presentation of the sucrose reward. Instances of anticipatory PER were summed across the five trials, defining Learning Response Scores (LRS) with a range of 0 to 5. Bees that scored 0 were omitted from the subsequent Kruskal-Wallis analyses (Fig. 3) to avoid confounding an individual bee’s ability to learn and inability to respond based on other factors, such as fatigue. The subsequent Chi-Square analyses (Fig. 4), however, included all bees tested, including bees with scores of 0, as we were interested in identifying possible treatment-induced differences in the proportion of bees responding (or able to respond) in each group. The result is that the sample sizes per group are slightly different for the two analyses. In addition, some subjects did not survive the incubation period between the learning assay and the recall assay, resulting in a slightly reduced number of subjects with scores reported in the recall assay.

Effects of treatments on proportions of PER responders during learning trials in intermediate age bees (A) and foraging age bees (B). Chi-Square tests, P < 0.05 for all differences. Asterisk = difference between Amitraz/acetone and Acetone only; diamond = difference between Amitraz/acetone and No treatment; star = difference between Acetone only and No treatment.

In intermediate age bees (Fig. 3), there was an overall significant difference in LRS across the Amitraz/acetone, Acetone only, and No treatment groups (Kruskal-Wallis statistic = 17.4, P = 0.0002). Amitraz/acetone bees of intermediate age had a significantly lower mean rank of LRS than No treatment bees (Dunn’s test, P = 0.0002). Acetone only bees had a significantly lower mean rank of LRS than No treatment bees (Dunn’s test, P = 0.0058). No difference was detected between the mean ranks of LRSs of Amitraz/acetone-treated and Acetone only bees (Dunn’s test, P = 0.971). No overall effect of treatment was detected in foraging age bees, (Kruskal-Wallis statistic = 1.437, P = 0.4874) (Fig. 3).

Post hoc pairwise analyses comparing age groups revealed a significant difference between Amitraz/acetone-treated foraging age bees and intermediate age bees, with the former having a higher mean LRS rank (Mann-Whitney U = 2767, P = 0.0315), and a significant difference between No treatment foraging age bees and intermediate age bees, with the latter having a higher mean LRS rank (Mann-Whitney U = 1217, P = 0.0116) (Fig. 3).

Proportions of anticipatory PERs during the learning trials were compared across treatment groups (Fig. 4). Responses from trial 1 provide a measure of initial responsiveness that is not attributable to learning. In intermediate age bees, those treated with Amitraz/acetone had a significantly higher proportion of PER than those treated with Acetone only (Chi-Square analysis, χ2 = 4.76, P = 0.0291) and No treatment bees (χ2 = 4.52, P = 0.0335) in trial 1. However, those treated with Amitraz/acetone had a significantly lower proportion of PER responses in trial 2 than those treated with Acetone only (χ2 = 5.406, P = 0.0201). Those treated with Amitraz/acetone had significantly lower proportions of PER than No Treatment bees in trials 2 (χ2 = 18.3, P < 0.0001), 3 (χ2 = 4.85, P = 0.0276), 4 (χ2 = 11.95, P = 0.0005), and 5 (χ2 = 14.52, P = 0.0001). Acetone only bees had significantly lower proportions of PER than No treatment bees in trials 2 (χ2 = 4.836, P = 0.0279), 4 (χ2 = 8.143, P = 0.0043), and 5 (χ2 = 25.19, P = 0.0001).

Foraging age bees treated with Amitraz/acetone had significantly higher proportions of PER responses than No treatment bees in trials 1 (χ2 = 4.822, P = 0.0281) and 5 (χ2 = 5.225, P = 0.0223). Foraging age bees treated with Acetone only had a significantly higher proportion of PER than No treatment bees in trial 2 (χ2 = 4.905, P = 0.0268).

No significant differences were detected in any pairwise comparisons for intermediate age bees at either 1–48 h post-training (Table 1). Foraging age bees treated with Amitraz/acetone had a significantly higher proportion of PER when tested for recall 1 h post-training than No treatment foraging age bees (χ2 = 3.934, P = 0.0473), but did not differ at this time point from Acetone only bees. Amitraz/acetone-treated foraging age bees at the 48-h recall trial performed significantly less well than their counterparts tested at 1 h (χ2 = 14.21, P < 0.0002). A significantly higher proportion of PER was observed in foraging age bees relative to intermediate age bees at the 1 h recall trial (χ2 = 5.356, P = 0.0207; Table 1).

Discussion

The results of the present study linked amitraz and acetone to subtle alterations of adult honey bee behavior. Our results are partially consistent with known actions of octopamine on honey bee sucrose sensitivity but reveal important caveats of experimental design that make interpretation of sublethal effects of xenobiotics a challenging endeavor. Overall, the results, while intriguing, do not raise major concerns regarding short term exposure of honey bees to amitraz.

Sucrose sensitivity

In newly emerged bees, comparisons between the Amitraz/acetone and Acetone only groups and between Acetone only and No treatment bees revealed significant differences, with sucrose sensitivity of the Acetone only group being reduced relative to the other groups. These results revealed an unexpected inhibitory effect of acute exposure to acetone on responses to low concentrations of sucrose. In contrast, there was no difference in sensitivity between the Amitraz/acetone and No treatment groups. At the four lowest concentrations tested, newly emerged bees had significantly different proportions of responders in the Amitraz/acetone and Acetone only groups and between the Acetone only and No treatment groups. One possible interpretation of these results is that the addition of amitraz to acetone acted on the central nervous system to restore acetone-diminished sensitivity of newly emerged bees to equal that of untreated newly emerged bees. A comparable pattern was observed in foraging age bees. Given previously demonstrated enhancing effects of octopamine treatment on sucrose sensitivity, our results potentially reflect interactions of amitraz with octopamine receptors37,38. In a pilot study (Supplementary Information 1), prior treatment of amitraz-exposed bees with epinastine, an octopamine receptor antagonist, blocked this apparent response to amitraz.

Olfactory association learning and recall

In intermediate age bees, the LRS of No treatment bees was significantly higher than that of the Amitraz/acetone and Acetone only groups. This pattern of results suggests that application of acetone 2 h prior to testing depressed the LRS, and that addition of amitraz to the acetone did not ameliorate the deficit. No difference was detected in the LRS of foraging age bees across treatment groups. In terms of the actions of amitraz, these findings were not as predicted, as previous studies reported that direct octopamine injections into the mushroom bodies of honey bees improved learning acquisition and memory formation23,24,39. Our results, however, align with another report based on topical exposure to amitraz16, which reported that amitraz exposure did not impact olfactory associative learning of worker honey bees of unknown age. Intermediate age bees appeared to be more sensitive to treatment than foraging age bees. Examination of response profiles during the training trial acquisition phase revealed a similar pattern of sensitivity to acetone, with a reduction in the proportion of bees responding with PER in Learning Trials 2–5 in intermediate age bees. The addition of amitraz to the solvent did not restore the proportion of PER responding during acquisition to the level seen in the No treatment group.

Amitraz/acetone and Acetone only had no effect on recall in intermediate age bees. By contrast, in foraging age bees, the difference between Amitraz/acetone and No treatment bees in the 1-hour recall test showed that under these test conditions, the treatment facilitated short-term recall. However, given that the Amitraz/acetone and Acetone only groups did not differ on this measure, the present results cannot be interpreted as supporting an amitraz effect mediated via octopamine receptors.

Experimental design considerations

The procedures used to implement the assays in this study included numerous pre- and post-testing checks to reduce potential confounding variables such as motivation and thirst. We included No treatment groups to check for independent effects of the solvent. We selected topical administration of the acaricide because the typical exposure of honey bees to amitraz is through topical contact with Apivar® strips. We applied treatments to the abdomen rather than to the thorax because a previous study reported that, after thoracic application, most residues remained in the thorax 24 h later, with almost no residues detectable in the head at this time40. We gave careful attention to the choice of solvent. Solvents such as acetone, dimethylformamide and dimethyl sulfoxide are often used in studies in which compounds are applied to the insect cuticle as a non-invasive alternative to injection or feeding41. Acetone was selected for use in the present study because it has been widely used in behavioral studies of honey bees for decades42,43,44. Our goal was to design assays sensitive enough to detect subtle, non-lethal effects of treatments on behavior. It is therefore perhaps not surprising that our assays were sensitive enough to detect subtle effects of exposure to acetone. Sensitivity to acetone varied with age and assay. Both newly emerged and foraging age bees exhibited reduced sucrose sensitivity after exposure to acetone, but in the olfactory association learning assay foraging age bees were more resilient to the effects of acetone than intermediate age bees. Future studies could bypass the use of solvents by housing bees in incubators in cages with Apivar® strips in a simulation of topical exposure to amitraz in the hive.

Significance of sublethal effects of acaricides and other xenobiotics

The results of the sucrose sensitivity studies suggest that it is possible to predict the impact of sublethal exposures to neuroactive substances used for pest control based on their known interactions with specific neurotransmitter receptors, and that, in some cases, sublethal exposures can facilitate performance in behavioral assays. Just as strikingly, however, these results suggest that detection of sublethal effects is highly dependent on specific assay procedures and will therefore resist easy generalization to field colonies. Results from the sucrose sensitivity tests suggest that amitraz may act as a weak octopaminergic agonist, but the effects of amitraz were obscured by independent responses to the acetone solvent.

There is a hypothetical possibility that an amitraz-induced increase in sucrose sensitivity could alter foraging patterns. Foragers specializing on nectar have lower GRS than pollen foragers and typically forage for higher concentrations of sucrose45. Foragers exposed to amitraz might return nectar with a lower sucrose concentration to the hive, resulting in a cumulative negative impact on colony energy storage.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are available through figshare at https://figshare.com/projects/Effects_of_amitraz_and_age_on_sucrose_sensitivity_learning_and_memory_recall_in_honey_bee_Apis_mellifera_workers/234524.

References

Han, B. et al. Life-history stage determines the diet of ectoparasitic mites on their honey bee hosts. Nat. Commun. 15, 725. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-44915-x (2024).

Genersch, E. & Aubert, M. Emerging and re-emerging viruses of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L). Vet. Res. 41, 54. https://doi.org/10.1051/vetres/2010027 (2010).

Martin, S. J. Global honey bee viral landscape altered by a parasitic mite. Science 336, 1304–1306. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1220941 (2012). https://www.science.org/doi/

Posada-Florez, F. et al. Deformed wing virus type A, a major honey bee pathogen, is vectored by the mite Varroa destructor in a non-propagative manner. Sci. Rep. 9, 12445. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47447-3 (2019).

Rosenkranz, P., Aumeier, P. & Ziegelmann, B. Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J. Invertebr Pathol. 103 (Suppl 1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2009.07.016 (2010). S96-119.

Hristov, P., Shumkova, R., Palova, N. & Neov, B. Factors associated with honey bee colony losses: a mini-review. Vet. Sci. 7, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci7040166 (2020).

Warner, S. et al. A scoping review on the effects of Varroa mite (Varroa destructor) on global honey bee decline. Sci. Total Environ. 906, 167492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167492 (2024).

Mullin, C. A. et al. High levels of miticides and agrochemicals in North American apiaries: implications for honey bee health. PLoS One. 5, e9754. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009754 (2010).

Rinkevich, F. D. Detection of Amitraz resistance and reduced treatment efficacy in the varroa mite, Varroa destructor, within commercial beekeeping operations. PLoS One. 15, e0227264. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. (2020).

Roeder, T. Octopamine in invertebrates. Prog. Neurobiol. 59, 533–561. (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00016-7 (1999).

Evans, P. D. & Gee, J. D. Action of formamidine pesticides on octopamine receptors. Nature 287, 60–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/287060a0 (1980).

Beeman, R. W. Recent advances in mode of action of insecticides. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 27, 253–281. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.27.010182.001345 (1982).

Birgül Iyison, N. et al. Are insect GPCRs ideal next-generation pesticides: opportunities and challenges. FEBS J. 288, 2727–2745. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15708 (2021).

Guo, L. et al. An octopamine receptor confers selective toxicity of amitraz on honeybees and Varroa mites. eLife, 10, e68268 (2021). https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.68268 (2021).

Di Noi, A., Casini, S., Campani, T., Cai, G. & Caliani, I. Review on sublethal effects of environmental contaminants in honey bees (Apis mellifera), knowledge gaps and future perspectives. Int. J. Env Res. Public. Health. 18, 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041863 (2021).

Rix, R. R. & Cutler, G. C. Acute exposure to worst-case concentrations of Amitraz does not affect honey bee learning, short-term memory, or hemolymph octopamine levels. J. Econ. Entomol. 110, 127–132. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tow250 (2017).

Gashout, H. A., Guzman-Novoa, E., Goodwin, P. H. & Correa-Benitez, A. Impact of sublethal exposure to synthetic and natural acaricides on honey bee (Apis mellifera) memory and expression of genes related to memory. J. Insect Physiol. 121, 104014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2020.104014 (2020).

Begna, T. & Jung, C. Effects of sequential exposures of sub-lethal doses of amitraz and thiacloprid on learning and memory of honey bee foragers, Apis mellifera. J. Asia-Pacific Entomol. 24, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aspen.2021.03.012 (2021).

O’Neal, S. T., Brewster, C. C., Bloomquist, J. R. & Anderson, T. D. Amitraz and its metabolite modulate honey bee cardiac function and tolerance to viral infection. J. Invertebr Pathol. 149, 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2017.08.005 (2017).

de Sanchez, B. Taste perception in honey bees. Chem. Senses. 36, 675–692. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjr040 (2011).

Menzel, R. Memory dynamics in the honeybee. J. Comp. Physiol. 185, 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003590050392 (1999).

Decourtye, A. et al. Comparative sublethal toxicity of nine pesticides on olfactory learning performances of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 48, 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-003-0262-7. (2005). https://doi-org.wake.idm.oclc

Hammer, M. & Menzel, R. Multiple sites of associative odor learning as revealed by local brain microinjections of octopamine in honeybees. Learn. Mem., 5, 146–156. (1998). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC311245/ (1998).

Mizunami, M. & Matsumoto, Y. Roles of octopamine and dopamine neurons for mediating appetitive and aversive signals in Pavlovian conditioning in crickets. Front. Physiol. 8, 1027–1027. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.01027 (2017).

Sabandal, J. M., Sabandal, P. R., Kim, Y. C. & Han, K. A. Concerted actions of octopamine and dopamine receptors drive olfactory learning. J. Neurosci. 40, 4240–4250. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1756-19.2020 (2020).

Wissink, M. & Nehring, V. Appetitive olfactory learning suffers in ants when octopamine or dopamine receptors are blocked. J. Exp. Biol. 224, jeb242732. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.242732 (2021).

Rembold, H., Kremer, J. & Ulrich, G. Characterization of postembryonic developmental stages of the female castes of the honey bee. Apis mellifera L Apidologie. 11, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:19800104 (1980).

Van Nest, B. N. The olfactory proboscis extension response in the honey bee: a laboratory exercise in classical conditioning. J. Undergrad. Neurosci. Edu. 16, 168–176 (2018). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6057764/

Pel, A. V., Van Nest, B. N., Hathaway, S. R. & Fahrbach, S. E. Impact of odorants on perception of sweetness by honey bees. PLoS ONEe. 18, e0290129. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0290129 (2023).

Amdam, G. V., Fennern, E., Baker, N. & Rascón, B. Honeybee associative learning performance and metabolic stress resilience are positively associated. PLoS ONE. 5, e9740. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009740 (2010).

Rascón, B., Hubbard, B. P., Sinclair, D. A. & Amdam, G. V. The lifespan extension effects of resveratrol are conserved in the honey bee and may be driven by a mechanism related to caloric restriction. AGING 4, 499–508. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.100474 (2012).

Suenami, S., Sata, M. & Miyazaki, R. Gustatory responsivenss of honey bees colonized with a defined or conventional gut microbiota. Microbes Environ. 39, ME23081. https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.ME23081 (2024).

Matsumoto, Y., Menzel, R., Sandoz, J. & Giurfa, M. Revisiting olfactory classical conditioning of the proboscis extension response in honey bees: a step toward standardized procedures. J. Neurosci. Meth. 211, 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.08.018 (2012).

Scheiner, R. et al. Standard methods for behavioural studies of Apis mellifera. J. Apic. Res. 52, 1–58. https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.52.4.04 (2013).

Behrends, A. & Scheiner, R. Evidence for associative learning in newly emerged honey bees (Apis mellifera). Anim. Cogn. 12, 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-008-0187-7 (2009).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Version 4.2.2, ‘Innocent and Trusting’) (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022).

Scheiner, R. et al. Behavioural pharmacology of octopamine, tyramine, and dopamine in honey bees. Behav. Brain Res. 136, 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4328(02)00205-X (2002).

Behrends, A. & Scheiner, R. Octopamine improves learning in newly emerged bees but not in old foragers. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 1076–1083. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.063297. (2012). https://doi-org.wake.idm.oclc.org

Mizunami, M. et al. Roles of octopaminergic and dopaminergic neurons in appetitive and aversive memory recall in an insect. BMC Biol. 7, https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-7-46. (2009)

Hillier, N. K., Frost, E. H. & Shutler, D. Fate of dermally applied miticides fluvalinate and amitraz within honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) bodies. J. Econ. Entomol. 106, 558–565. https://doi.org/10.1603/EC12300 (2013).

Barron, A. B. et al. Comparing injection, feeding and topical application methods for treatment of honeybees with octopamine. J. Insect Physiol. 53, 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2006.11.009 (2007).

Robinson, G. E. Effects of a juvenile hormone analogue on honey bee foraging behaviour and alarm pheromone production. J. Insect Physiol. 31, 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1910(85)90003-4 (1985).

Robinson, G. E. Regulation of honey bee age polyethism by juvenile hormone. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 20, 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00300679 (1987).

Robinson, G. E. & Ratnieks, F. Induction of premature honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) flight by juvenile hormone analogs administered orally or topically. J. Econ. Entomol. 80, 784–787. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/80.4.784 (1987).

Scheiner, R., Barnert, M. & Erber, J. Variation in water and sucrose responsiveness during the foraging season affects proboscis extension learning in honey bees. Apidologie 34, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2002050 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steven A. Cayea for assistance with beekeeping, behavioral testing, and collection of data in Supplementary Information 1. Funds in support of this project were provided by the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation of Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation of Winston-Salem, NC, USA, to S.E.F.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.W.H. and S.E.F. designed the experiments, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the main manuscript text. E.W.H. collected test subjects, administered treatments, collected behavioral data, and prepared the figures. S. E. F. provided funding and project oversight. Both authors reviewed the manuscript and made revisions in response to reviewers’ comments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, E.W., Fahrbach, S.E. Subtle effects of acetone and amitraz on sucrose sensitivity and recall in honey bees. Sci Rep 15, 20867 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06466-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06466-z