Abstract

To evaluate the effectiveness of vertical asymmetry analysis of the macular microvasculature in high myopia patients with open-angle glaucoma (OAG). Participants were divided into two groups: those with high myopia (group 1) and those with both high myopia and OAG (group 2). Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness, vessel density (VD), and the absolute vertical difference of RNFL thickness (vdRNFL) and VD (vdVD) were compared. A logistic regression analysis determined the factors associated with OAG, and diagnostic accuracy was assessed using the area under the curve (AUC). Mean RNFL thickness was 91.2 ± 11.5 and 78.2 ± 13.0 μm (P < 0.001) and the VD of the full area was 17.5 ± 1.9 and 16.6 ± 2.4 mm−1 (P = 0.040) in group 1 and group 2, respectively. The vdRNFL was not significantly different (P = 0.385), whereas the vdVD showed a significant difference (P < 0.001) between the groups. Multivariate analysis revealed that mean RNFL thickness (OR 0.88, P < 0.001) and vdVD (OR 3.07, P = 0.004) were significantly associated with OAG in high myopia patients. The AUC for vdVD was 0.82 (95% CI 0.73–0.90) and the combining mean RNFL thickness with vdVD yielded the highest AUC (0.91, 95% CI 0.85–0.96). For diagnosing OAG in high myopia patients, vertical asymmetry analysis of the macular microvasculature, combined with mean RNFL thickness, is advantageous.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of myopia is increasing, with rates as high as 80% in Asia and 22.9% in other regions of the world1,2. In particular, high myopia, defined as a spherical equivalent (SE) ≤ -6.0 diopters or axial length ≥ 26.0 mm, is distinguished by the axial elongation of the eye3. This consistent stretching of the posterior wall may lead to various structural alterations, potentially resulting in visual impairments such as retinal detachment, macular holes, choroidal neovascularization, and retinoschisis4. Moreover, high myopia is associated with retinal thinning due to the elongation of the eyeball, which can culminate in thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL)5. Changes in RNFL thickness are crucial for the diagnosis and management of glaucoma, with variations in thickness owing to high myopia potentially acting as a confounding factor in the diagnosis of this condition.

The development of optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) has enabled noninvasive visualization of the fine microvasculature across multiple retinal layers. Numerous studies have documented impairments in retinal microvasculature in patients with glaucoma using OCTA6,7. Additionally, asymmetrical analysis of retinal microvasculature damage has been reported to aid in the diagnosis of glaucoma8,9. Hong et al.8 reported that the discrepancy in hemiretinal vessel area density between superior and inferior regions was more pronounced in early glaucoma, suggesting its diagnostic utility for early open-angle glaucoma (OAG). Given these insights, it was hypothesized that, in cases of high myopia, where sole reliance on RNFL thickness might be inadequate for glaucoma diagnosis, vertical asymmetry analysis of the retinal microvasculature could provide supplementary diagnostic value.

The purpose of this study was to explore the effectiveness of vertical asymmetry analysis of the retinal microvasculature in facilitating the early OAG diagnosis among patients with high myopia.

Methods

Patients

This retrospective, cross-sectional study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of Konyang University Hospital, Daejeon, Republic of Korea (No. 2024-04-017). The study involved a review of the medical records of patients who attended our retinal and glaucoma clinics between June 2023 and February 2024. Owing to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of Konyang University Hospital. We collected data on medical history, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular pressure (IOP), SE, and axial length. Participants were classified into two groups: patients with high myopia (Group 1), and patients with both high myopia and OAG (Group 2). High myopia was defined as having an axial length ≥ 26 mm. The diagnosis of OAG was made by glaucoma specialists, based on the presence of neural rim loss observed during a dilated stereoscopic examination of the optic nerve, glaucomatous visual field defects detected on standard automated perimetry (defined as a cluster of ≥ 3 points with P < 0.050; or a glaucoma hemifield test result outside normal limits), and/or RNFL loss visible on peripapillary assessment using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT), along with open angles confirmed by indentation gonioscopy. Only patients with early-stage OAG, defined by a 24–2 mean deviation > − 6 dB were included. Exclusion criteria were a history of ocular diseases other than high myopia and OAG, secondary glaucoma, angle-closure glaucoma, severe cataract potentially affecting BCVA, an IOP ≥ 21 mmHg, a BCVA < 30/40, and prior intraocular surgery excluding cataract extraction. We also excluded high myopia patients with severe structural changes such as extensive chorioretinal atrophy or posterior staphyloma, which might lead to segmentation errors in OCTA imaging.

OCT and OCTA measurements

OCT measurements were conducted by an experienced examiner using a Cirrus HD OCT 6000 (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA; version 10.0. The 512 × 128 macular cube and 200 × 200 optic disc cube scanning protocols were used for measuring ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GC-IPL) and RNFL thicknesses. Peripapillary RNFL thickness was measured using the optic disc cube scan protocol, which captures a 6 × 6 mm area centered on the optic nerve head at a resolution of 200 × 200 pixels. This scan provided values for the mean RNFL thickness, as well as for each of the four quadrants: superior, temporal, inferior, and nasal. GC-IPL thickness was assessed using the system’s automated ganglion cell analysis algorithm. The analysis yielded both the average GC-IPL thickness and regional measurements from six sectors: superior, superonasal, inferonasal, inferior, inferotemporal, and superotemporal.

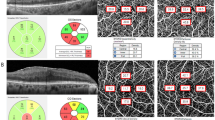

OCTA images were captured with a Cirrus 6000 HD-OCT equipped with AngioPlex software (Carl Zeiss Meditec). A fovea-centered 6 × 6 mm scan was performed, from which en-face OCTA images were automatically produced using the AngioPlex optical microangiography algorithm. The 6 × 6 mm scan included a 1 mm center, four quadrant sectors equivalent to the inner circle of the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS), and another four quadrant sectors matching the outer circle of the ETDRS. Vessel density (VD, defined as the total length of perfused vasculature per unit area), within the superficial capillary plexus (extending from the internal limiting membrane to the inner plexiform layer) was automatically quantified by the software (Fig. 1). Images affected by fixation loss, segmentation errors, motion artifacts, or with a signal strength < 9 were excluded from analysis.

Optical coherence tomography angiography image (6 × 6 mm) centered on the fovea. En-face image of the superficial capillary plexus overlaid with the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study grid. Blue boxes indicate the automatic measurements for vessel density of inner and outer circles and the full area. C, central; IS, inner superior; IT, inner temporal; II, inner inferior; IN, inner nasal; OS, outer superior; OT, outer temporal; OS, outer inferior; ON, outer nasal.

The vertical difference in RNFL (vdRNFL) and GC-IPL (vdGC-IPL) was defined as the absolute difference in thickness between the superior and inferior sectors, and the vertical difference in VD (vdVD) was defined as the absolute difference in VD between the superior and inferior sectors, in accordance with previous studies8,9,10,11. The normalized asymmetry index of RNFL (aiRNFL), GC-IPL (aiGC-IPL), and VD (aiVD) were calculated as (superior − inferior)/(superior + inferior).

Statistical analyses

Demographic characteristics, OCT, and OCTA parameters were analyzed using an independent t-test for continuous data, and the chi-square test for categorical data. To compare the normalized asymmetry index between the groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. To identify factors associated with OAG among patients with high myopia, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted. The diagnostic effectiveness of various factors was evaluated through analysis of the area under curves (AUCs). DeLong’s test was applied to determine the statistical significance of differences between AUCs derived from different models. All statistical procedures were executed using R Studio (version 1.1.453; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Demographics

The study included a total of 101 eyes: 51 in Group 1 and 50 in Group 2. The mean ages were 41.4 ± 14.4 years for group 1 and 43.6 ± 11.8 years for Group 2, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.409) (Table 1). The mean axial lengths were 27.2 ± 1.1 (minimum: 26.0 mm, maximum: 30.8 mm) and 27.2 ± 1.1 (minimum: 26.0 mm, maximum: 30.3 mm), respectively (P = 0.908). Other demographic and clinical characteristics, including sex, BCVA, SE, and IOP showed no significant difference between the groups. For Group 2, the mean deviation was − 3.71 ± 3.16 dB, the pattern standard deviation was 4.43 ± 2.19 dB, and the visual field index was 90.17 ± 9.70%. In Group 2, 22 eyes were diagnosed with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) and 28 with normal tension glaucoma (NTG).

OCT and OCTA parameters

Since we excluded cases with structural abnormalities in the macula, there were no cases of segmentation errors or those requiring manual adjustment. The mean RNFL thickness was 91.2 ± 11.5 and 78.2 ± 13.0 μm in group 1 and group 2, respectively, which was significantly different (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Similarly, sectoral thicknesses, with the exception of the nasal sector, followed the pattern of the mean thickness. The vdRNFL was 14.4 ± 11.5 μm for group 1 and 16.4 ± 11.9 μm for group 2, showing no significant difference (P = 0.385). The median of aiRNFL was 0.004 (interquartile range − 0.042 to 0.060) for group 1 and 0.056 (interquartile range − 0.027 to 0.129) for group 2, respectively (P = 0.034). The average and sectoral GC-IPL thicknesses were significantly thinner in Group 2 (all P < 0.001), and vdGC-IPL (P = 0.040) and aiGC-IPL (P = 0.010) also showed a significant difference between the two groups.

The VD of the full area was 17.5 ± 1.9 and 16.6 ± 2.4 mm−1 in group 1 and group 2, respectively, which was significantly different (P = 0.040) (Table 3). The mean VD of the outer circle differed significantly (P = 0.011), but the mean VD of the inner circle did not (P = 0.509). The vdVD of the outer circle was 0.7 ± 0.6 and 2.6 ± 2.1 mm−1, respectively, which was significantly different (P < 0.001). The median of aiVD of the outer circle was 0.008 (interquartile range − 0.009 to 0.031) for group 1 and 0.044 (interquartile range − 0.006 to 0.113) for group 2, respectively (P = 0.001).

Logistic regression analyses and diagnostic accuracy based on the AUC

Univariate analysis revealed significant associations between the presence of OAG in patients with high myopia and mean RNFL thickness (OR 0.85, P < 0.001), average GC-IPL (OR 0.82, P < 0.001), VD of the outer circle (OR 0.76, P = 0.018), and vdVD of the outer circle (OR 3.63, P < 0.001) (Table 4). Multivariate analysis maintained the significance of mean RNFL thickness (OR 0.88, P < 0.001) and vdVD of the outer circle (OR 3.07, P = 0.004).

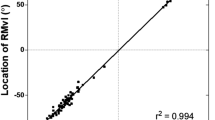

Diagnostic accuracy, measured using the AUC, showed mean RNFL thickness at 0.85 (95% CI 0.79–0.93, P < 0.001), average GC-IPL at 0.83 (95% CI 0.75–0.91, P < 0.001), VD of the outer circle at 0.69 (95% CI 0.59–0.79, P = 0.001), aiRNFL at 0.62 (95% CI 0.51–0.73, P = 0.034), aiGC-IPL at 0.65 (95% CI 0.54–0.76, P = 0.010), aiVD of the outer circle at 0.69 (95% CI 0.58–0.80, P = 0.001), vdRNFL at 0.55 (95% CI 0.44–0.67, P = 0.350), vd GC-IPL at 0.66 (95% CI 0.55–0.77, P = 0.006), and vdVD of the outer circle at 0.82 (95% CI 0.73–0.90, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The AUCs for the combination of vdVD of the outer circle and VD of the outer circle, vdVD of the outer circle and vdRNFL, vdVD of the outer circle and average GC-IPL, and vdVD of the outer circle and mean RNFL thickness were 0.82 (95% CI 0.74–0.90, P < 0.001), 0.82 (95% CI 0.74–0.90, P = 0.041), 0.86 (95% CI 0.80–0.93, P < 0.001), and 0.91 (95% CI 0.85–0.96, P < 0.001), respectively. The AUC of vdVD of the outer circle was not significantly different than that of mean RNFL (P = 0.409). Among these, the combination of mean RNFL thickness and vdVD of the outer circle showed the highest AUC, significantly greater than all other parameters (all P < 0.001).

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the mean retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness, average ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) thickness, vessel density (VD), the absolute vertical difference in RNFL (vdRNFL), GCIPL (vdGCIPL), and vessel density (vdVD), and the combination of mean RNFL thickness and vdVD. The area under the curve (95% CI) was 0.85 for mean RNFL thickness (0.79–0.93), 0.83 (0.75–0.91) for average GCIPL, 0.65 (0.54–0.76) for VD of the full area, 0.69 (0.59–0.79) for VD of the outer circle, 0.55 (0.44–0.67) for vdRNFL, 0.75 (0.62–0.87) for vdGCIPL, 0.82 (0.73–0.90) for vdVD, and 0.91 (0.85–0.96) for the combination of mean RNFL thickness and vdVD.

In subgroup analysis, the AUCs were 0.62 (95% CI 0.48–0.76, P = 0.106) for vdRNFL, 0.67 (95% CI 0.52–0.83, P = 0.019) for aiRNFL, 0.75 (95% CI 0.62–0.87, P = 0.001) for vdGC-IPL, 0.72 (95% CI 0.58–0.87, P = 0.003) for aiGC-IPL, 0.87 (95% CI 0.79–0.95, P < 0.001) for vdVD of the outer circle, and 0.79 (95% CI 0.63–0.95, P < 0.001) for aiVD of the outer circle in POAG group. In NTG group, the AUCs were 0.50 (95% CI 0.37–0.74, P = 0.975) for vdRNFL, 0.58 (95% CI 0.45–0.72, P = 0.230) for aiRNFL, 0.59 (95% CI 0.45–0.73, P = 0.200) for vdGC-IPL, 0.59 (95% CI 0.45–0.73, P = 0.186) for aiGC-IPL, 0.78 (95% CI 0.67–0.89, P = 0.001) for vdVD of the outer circle, and 0.61 (95% CI 0.46–0.75, P = 0.111) for aiVD of the outer circle.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated peripapillary RNFL and GC-IPL thicknesses, as well as macular VD and their vertical asymmetry, among patients with high myopia and those with both high myopia and early OAG. Our findings revealed that high myopia patients with OAG showed reduced RNFL and GC-IPL thicknesses, and lower VD compared to those with only high myopia. While the vdRNFL did not significantly differ between the two groups, the vdVD was significantly higher in patients with OAG. Both mean RNFL thickness and vdVD merged as significant factors associated with OAG in high myopia patients. Furthermore, when evaluated independently, these factors displayed good diagnostic accuracy for OAG in high myopia patients. Notably, their combined analysis provided the highest diagnostic precision.

The mean RNFL thickness was significantly different between the two groups and was associated with OAG in patients with high myopia, also showing good diagnostic accuracy for OAG within this demographic. Although RNFL thickness can be influenced by high myopia, it remains a crucial metric for the diagnosis of early OAG, especially when the measurement of RNFL thickness is not significantly affected by the enlargement of peripapillary chorioretinal atrophy. Conversely, the vdRNFL was not significantly different between the two groups and did not demonstrate a strong diagnostic efficacy for OAG in high myopia patients. The vdRNFL analysis is widely recognized as highly useful for diagnosing glaucoma10,12. Additionally, Lin et al.13 reported that the difference in RNFL thickness between superior and inferior quadrants was significantly different between high myopia controls and high myopia patients with NTG, suggesting its potential as an auxiliary tool for the early detection of NTG in high myopia patients. However, the aforementioned study also showed that while the diagnostic performance of mean RNFL thickness based on AUC was 0.842, that of RNFL vertical asymmetry was lower at 0.663, indicating limited diagnostic value, which is consistent with our findings. In our subgroup analysis, both NTG and POAG groups showed limited diagnostic performance of vdRNFL. However, further studies with a larger number of cases are needed to enable a more detailed analysis according to glaucoma type. As a result, the analysis of vdRNFL is considered to have a limited role in the diagnosis of OAG among patients with high myopia.

Hou et al.6 reported that superficial macular VD, as measured with OCTA, was significantly lower in primary OAG patients compared to normal controls. Similarly, Scripsema et al.7 found that the annular perfused capillary density in NTG patients was significantly lower than that in healthy subjects. Meanwhile, high myopia has also been linked to decreased macular VD. A previous study reported a reduction in VD within both the superficial and deep capillary plexuses in cases of high myopia14. Furthermore, Am et al.15 reported that the presence of both high myopia and OAG resulted in a more pronounced decrease in microvascular attenuation than when either condition was present alone. The findings of our study, showing that the VD of the full area in group 2 was significantly lower than in group 1, align with these previous reports. Therefore, the combination of high myopia with OAG may lead to further impairment of the retinal microvasculature.

Hong et al.8 reported that the mean asymmetry values of peripapillary vessel area density, adjusted for age, were significantly higher in mild, moderate, and severe primary OAG compared to normal controls. Chang et al.9 reported that the discriminative ability of macular perfusion density asymmetry for distinguishing glaucoma patients with and without visual field defects was significantly greater than that of structural asymmetry. Consistent with these findings, our study found that the vdVD in group 2 was significantly higher than that in group 1. This suggests that the asymmetry in macular microvasculature attributed to OAG persists even in the presence of high myopia. However, the presence of diffuse chorioretinal atrophy in the macula, which may not be symmetric and could lead to segmentation errors resulting in inaccurate VD measurements, may limit the effectiveness of analyzing macular microvasculature for glaucoma diagnosis.

Chang et al.9 reported that the AUC for outer macular perfusion density asymmetry, as a means to differentiate between preperimetric and perimetric glaucoma groups, was 0.86. This AUC was higher than that obtained through structural asymmetry analysis. Similarly, Smith et al.11 reported an AUC of 0.83 for the perfusion asymmetry index in the diagnosis of glaucoma. Our research indicated that the AUC for the vdVD of the outer circle in diagnosing early OAG in high myopia patients was 0.82, aligning with findings from previous studies. Despite the challenges high myopia may pose, analyzing macular microvasculature asymmetry continues to be useful in the diagnosis of OAG. Although the vdRNFL did not show strong diagnostic accuracy, the mean RNFL thickness demonstrated good diagnostic performance for early OAG in high myopia patients. Moreover, the combined analysis of mean RNFL thickness and vdVD exhibited the highest AUC for identifying early OAG among various parameters in high myopia patients. Previous research supported our findings, showing that the combined evaluation of RNFL thickness and hemiretinal difference in vessel area density provided a significantly higher AUC than the evaluation of RNFL thickness alone for distinguishing primary OAG from healthy eyes8. Therefore, considering both mean RNFL thickness and macular microvasculature asymmetry in patients with high myopia is highly advantageous for diagnosing OAG.

This study had certain limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study may introduce some selection bias. Second, the findings of the study may not be applicable in cases with diffuse chorioretinal atrophy associated with high myopia. Third, visual field testing is not routinely performed in all patients with high myopia; therefore, most patients in Group 1 did not undergo the test, and visual field data for this group could not be provided. Fourth, although including an additional group such as a non-myopic OAG group could have provided a more accurate and comprehensive interpretation, this was not feasible due to insufficient data. In additiona, while OCTA has been reported to demonstrate good reproducibility in structurally normal eyes and in highly myopic eyes without morphological abnormalities, its reproducibility may be influenced by axial length16,17. Since repeated OCTA scans were not performed in our study, we were unable to assess the reproducibility of the data used. One strength of our study is the provision of a tool that effectively assesses OAG in high myopia patients, a group that could otherwise complicate the diagnosis of OAG.

In conclusion, high myopia patients with OAG had significantly reduced RNFL thickness and lower VD compared to those without OAG. When both conditions, which affect RNFL and VD coexist, their impacts on thickness and VD are exacerbated. Although there was no significant difference in vdRNFL between the groups, the vdVD of the outer circle differed significantly and was also a significant factor associated with OAG in high myopia patients. The vdVD demonstrated good diagnostic accuracy for OAG in high myopia patients based on AUC analysis, and the combination of mean RNFL thickness and vdVD achieved the highest AUC of all evaluated parameters. These findings could aid clinicians in diagnosing OAG in patients with high myopia within clinical settings.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Holden, B. A. et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 123(5), 1036–1042 (2016).

Luu, C. D., Lau, A. M. & Lee, S.-Y. Multifocal electroretinogram in adults and children with myopia. Arch. Ophthalmol. 124(3), 328–334 (2006).

Lee, M. W., Lee, S.-E., Lim, H.-B. & Kim, J.-Y. Longitudinal changes in axial length in high myopia: A 4-year prospective study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 104(5), 600–603 (2020).

Ikuno, Y. Overview of the complications of high myopia. Retina 37(12), 2347–2351 (2017).

Lee, M.-W. et al. Longitudinal changes in peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in high myopia: A prospective, observational study. Ophthalmology 126(4), 522–528 (2019).

Hou, H. et al. Macula vessel density and thickness in early primary open-angle glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 199, 120–132 (2019).

Scripsema, N. K. et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography analysis of perfused peripapillary capillaries in primary open-angle glaucoma and normal-tension glaucoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 57(9), OCT611–OCT620 (2016).

Hong, K. L. et al. Hemiretinal asymmetry in peripapillary vessel density in healthy, glaucoma suspect, and glaucoma eyes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 230, 156–165 (2021).

Chang, P.-Y. et al. Asymmetry analysis of optical coherence tomography angiography macular perfusion density measurements in preperimetric and perimetric glaucoma. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 14781 (2020).

Lin, P.-W. et al. Intraocular retinal thickness asymmetry in early stage of primary open angle glaucoma and normal tension glaucoma. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 11(8), 1342 (2018).

Smith, C. A. et al. Asymmetry analysis of macular optical coherence tomography angiography in patients with glaucoma and healthy subjects. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 104(12), 1724–1729 (2020).

Seo, J. H. et al. Detection of localized retinal nerve fiber layer defects with posterior pole asymmetry analysis of spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53(8), 4347–4353 (2012).

Lin, P.-W., Chang, H.-W. & Poon, Y.-C. Retinal thickness asymmetry in highly myopic eyes with early stage of normal-tension glaucoma. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 6660631 (2021).

Shuaib, A. et al. Correlation of the macular microvasculature to the axial length in pediatric patients with high axial refractive errors. Eye 38(3), 507–513 (2024).

Am, S. et al. The effect of myopia on vessel density in glaucomatous patients by optical coherence tomography angiography. Clin. Ophthalmol. 17, 2429–2441 (2023).

Li, M. et al. The repeatability of superficial retinal vessel density measurements in eyes with long axial length using optical coherence tomography angiography. BMC Ophthalmol. 18, 1–7 (2018).

Lee, W. H. et al. Long-term repeatability of peripapillary optical coherence tomography angiography measurements in healthy eyes. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 23832 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design and conduct of the study (M.W.L., K.S.P.); Collection of data (M.W.L., K.S.P., J.T.K.); Analysis and interpretation of data (M.W.L., H.B.L.); Writing the article (M.W.L., K.S.P.); Critical revision of the article (M.W.L., K.H.L.); Final approval of the article (K.S.P., J.T.K., K.H.L., H.B.L., M.W.L.).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, KS., Kim, JT., Lee, KH. et al. Macular microvasculature asymmetry in high myopia patients with early open-angle glaucoma. Sci Rep 15, 22928 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06774-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06774-4