Abstract

The automotive market is moving fast towards electric vehicles (EV). The ever-growing EV technology and associated service infrastructure, appropriate policies and regulations among other factors are increasing the user’s acceptance and confidence in the EV industry, resulting in the growth of EV sales. The existing barriers to the expansion of EV sales such as relatively high purchase prices, the small number of charging stations, uneven distribution of charging stations, and charging times, tend to disappear over time and the expectation is that soon EVs will constitute a significant share of new car sales globally. This work tackles specifically the charging time problem and proposes solutions for coordinating the charging of a group of electric vehicles in a charging station based on the metaheuristic teaching–learning-based optimization (TLBO) and on a specialized heuristic technique. The proposed methods seek to deliver as much energy as possible to vehicles’ batteries without violating the constraints and limits of the distribution grid. TLBO is an efficient metaheuristic algorithm that requires few tuning parameters and does not depend on historical data to obtain an optimal solution for an optimization problem. Also, the specialized heuristic technique makes use of specific knowledge about the optimal charging problem to obtain a fast, high-quality solution. Simulation results obtained from the TLBO algorithm are presented alongside those from the heuristic method, with discussions, performance comparisons, and recommendations for practical applications. It will be seen that the proposed approaches are able to meet the efficiency requirement expected by EV customers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electric vehicles (EVs) have been mass-produced in the last years, driven mainly by government incentives and regulations that aim to reduce the emission of pollutant and greenhouse effect gases. In 2019, EV sales represented about 3% of the world market and are expected to reach up to 32% by 20301. As users replace their internal combustion-based vehicles with electric ones, they expect to have access to an appropriate infrastructure, including plenty of charging stations, as occurs with today’s gas stations. Charging stations must be available at parking lots in the workplace, shopping malls and so on. Of course, users must be able to charge their vehicles at home as well.

The energy demand coming from the charging of EVs will lead to changes in the operation and planning of distribution systems. This scenario is even more challenging in regions with a higher concentration of EVs. For instance, it is expected that the participation of EVs in automobile sales in 2030 in China will be close to 50%, followed by Europe with more than 40%, as shown in Fig. 1.

Outlook for EV market share by major region. Source:1.

The sales growth will result in regions with a high penetration of EVs. In2, the authors evaluated actual data from more than 76 thousand EVs travelling for a month in Beijing, China, and observed that most users charge their vehicles at night. During daylight, in-transit users charge their vehicles in parking lots and charging stations spread around town. They tend to look for a charging station whenever the state-of-charge (SOC) of the batteries is between 20 and 90%.

The consequences of charging EVs without proper coordination are mainly twofold: (a) effects on the operation of the distribution network to which the charging station is connected; and (b) overall customer dissatisfaction due to inefficient/poor charging scheduling.

The lack of an appropriate charging coordination may significantly affect the operation of the distribution network, increasing the power losses, affecting the voltage profile, and impacting other aspects related to the quality of the energy supplied, such as voltage unbalance and harmonic distortion. According to3, power losses and voltage drops may reach 6% and 10,3% respectively in a region with 30% penetration of EVs using 4 kW chargers, especially between 6 and 9 pm. The authors suggest the use of smart meters to control the charging process, and the increase of the transformers’ rated capacity to cope with the additional demand required by the EVs. Deterministic and stochastic programming techniques were used to minimize power losses during the charging period; however, 11 kWh batteries and 4 kW chargers were used.

In4, the authors showed that the impact of EVs in the overall residential demand is limited, however, the peak demand due to their charging is significant. The presence of only one EV with charging level 2 (6.6 kW) would make the transformer of a residential area operate around 15% above its rated capacity for an hour, reducing its useful life. Considering a 50% penetration of EVs, a significant increase in the demand peaks and a potential shift in the energy consumption profile may amplify the criticality of peak hours in terms of the grid operation. It is possible to observe this effect in Fig. 2, which illustrates the residential demand and the extra demand caused by EVs.

Residential electricity demand with 10% and 50% EV penetration. Source:4.

Distribution networks may not be prepared to meet this additional demand. In5, the authors presented a study with the impacts of EV charging in the distribution grid considering several networks in the Netherlands. The non-coordinated EV charging increases the overload of the network’s equipment. This overload causes a significant reduction in their service lives, also increasing the operational costs, considering the early equipment replacement and non-supplied energy. Those increases may reach 20% if compared to a scenario with a coordinated charging scheme.

In6 a solution was proposed to minimize the cost of energy in parking lots that offer the EV charging service. This cost is variable, and the operator must decide the amount of energy that will be purchased at the beginning of each five-minute period without knowing how much it will be charged. The authors developed a solution based on machine learning to decide that amount of energy to be purchased from a small quantity of historical data.

In7 a second-order conic model and a linear model were implemented for the coordinated charging of EVs. These methods were compared with an uncoordinated charging process, where the vehicles were connected to either a 32- or a 136-bus distribution system. The models were intended to minimize both the non-supplied energy to the EVs’ batteries and the charging times. The authors concluded that uncoordinated charging may lead to voltage and current violations in the grid. When the energy coordination was applied, all vehicles reached their full charge, and no grid violations were observed.

In8 historical data from the use of each vehicle were used to estimate when vehicles leave the residential household and to determine the charging period available. Therefore, the kind of charging (fast, normal) can be determined, as well as whether the vehicle can supply the grid. The authors applied machine learning with further classification techniques to solve the problem and compared them. Long short-term memory (LSTM) recurrent neural networks obtained the best results, with the best power supply pattern in 95% of the simulated cases, with a ± 0.71% error. Deep Neural Networks (DNN) did not perform as expected, since the best supply pattern was obtained in 88.2% of the cases, with ± 20.2% error.

In9, the authors proposed a model for the coordinated charging of EVs with the application of reinforced learning to simulate the charging of 50 EVs in a region with 250 households. The proposed model sets up a charging schedule for the vehicles along the available time slot, neglecting the EVs’ arriving and leaving times. For the simulated scenarios, the were no operational violations in the grid and the variance of the load in the region decreased by 65% in comparison with an uncoordinated scenario.

Reference10 proposed a two-level optimal scheduling strategy of electric vehicle charging aggregator based on charging urgency. The vehicles plugged at charging stations are separated into two groups based on the charging urgency. The first group contains the vehicles that have reached the latest charging time, while the second group contains vehicles that have not yet reached the latest charging time. Vehicles from the first group must be charged immediately without interruption, and there is no room for scheduling, while vehicles from the second group may be subject to scheduling. The main idea is to dispatch the load aiming at peak shaving and valley filling, thus optimizing the distribution grid operation.

In11 a charging strategy was proposed for optimal operation of distribution grids. Basically, the idea is to minimize the real power losses of the distribution grid, while meeting the charging needs. The proposed optimization model considers the different types of chargers, and the optimal strategy is obtained by commercial solvers. Reference12 also proposed a model for determining the optimal EV charging scheduling while minimizing the network’s real power losses using the metaheuristic Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). The simulation results showed that the system peak demand can be substantially reduced, leading ultimately to a reduction in the total system losses.

Reference13 proposed an optimization model to minimize the load fluctuations in the network and the operation and EV charging costs. The problem was solved by the metaheuristic Improved Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm. The proposed method not only meets users’ charging needs but also reduces the peak-valley difference of load and the cost of online distribution and overall operation and maintenance.

Reference14 discussed the importance of EV optimal charging coordination in distribution networks that contain some penetration of distributed generated. A model based on minimizing the distribution system’s real power losses is proposed to smooth the system’s load curve, guarantee the EV charging processes as well as grid safety.

Reference15 proposed a method for optimal EV charging considering the presence of solar photovoltaic generation in DC microgrids. A multi-objective optimization model was proposed to minimize the cost of electricity purchase and the energy circulation of the storage batteries. The model considers constraints such as EVs’ charging time, the range of the charging/discharging power and the SOC (state of charge) of the storage batteries, power supply rate of the distribution network and system power balance. The optimal solution was obtained by the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II).

In16 a two-level optimization strategy for residential areas considering the customer’s urgency was proposed. The upper-level optimization model is based on the travel characteristics of residential areas and typical charging scenarios, so the optimal charging power in each time interval is modeled and solved, and the optimal charging power distribution curve is obtained. In the lower-level optimization model the charging urgency is calculated according to the received EV state information, and the residential users are guided to conduct orderly charging in combination with the power distribution curve. The model was implemented with AMPL mathematical modeling language and implemented through CPLEX calculation software. Compared with dumb charging, the ordered charging control strategy improves the capacity of the residential distribution network to absorb EVs, significantly reducing the overall load fluctuation, which is important to safe and stable operation of the power grid. By shifting the charging time from the peak period to the electricity price valley period, the income of charging pile agents is effectively increased, and their enthusiasm to participate in the charging management of EVs is mobilized. Finally, through the guidance of the lower level ordered charging controller, the actual needs of EV users can be better met.

In17, the author presented a dynamic programming model to decide whether an EV should be charged or not based on the electricity price, its SOC, and the pre-determined trajectory. The price was found to be a relevant factor in this decision. The model also provides a charging schedule to minimize the charging cost. Also, the results were compared with the costs associated with internal combustion vehicles. Finally, the author concluded that uncoordinated charging is the worst strategy, resulting in larger operational costs than the operation with internal combustion vehicles only.

Reference18 has a comprehensive review for the use of supervised and unsupervised Machine Learning as well as Deep Neural Networks for charging behavior analysis and prediction. A detailed comparative analysis was carried out and an important discussion was made about the lack of public charging data sets and the lack of high-dimensional data.

The description above clearly shows that the effects of the EV charging processes on distribution grids and in the consumption profile cannot be ignored. The lack of planning and control strategies from the supply side as well as from the demand side may result in serious problems for the electrical energy infrastructure and for the economy of regions where mobility is dependent on plug-in EVs.

As pointed out earlier, the second main consequence of charging EVs without proper coordination is the inefficiency of charging times and customer overall dissatisfaction. Basically, the idea of an efficient charging station resides in a fast-charging process and the ability to cope with the dynamic environment, where vehicles with different states of charge may be connected and disconnected at any time.

From the literature review above, it can be concluded that most EV charging methods:

-

Involves the inclusion of the electric power system model, which can be AC or DC.

-

Focus on obtaining the system’s optimal operating condition (minimum cost, minimum power losses, minimum power fluctuation, and so on).

-

Use conventional programming techniques, in particular commercial solvers, as well as metaheuristic methods and specialized heuristic techniques.

It must be emphasized that the main goal is to come up with an optimal charging schedule that would fully charge the batteries in the least time. Including the network model into the optimization model is a challenge in the sense that it increases significantly the computation burden. Also, this type of model requires a large amount of data. On the other hand, a practical EV optimal charging process requires great efficiency in terms of making decisions on the charging process, and the minimum amount of external data.

The idea of this paper is to fill this gap and to contribute with solutions for the challenges the popularization of EVs has been posing. Methods are proposed to organize and coordinate the charging of EVs in such a way to attend to the users’ objectives and at the same time to preserve the operating conditions of distribution grids as well as the service life of their equipment.

More specifically, the idea is to propose optimal charging schemes for EVs being charged at charging stations without violating the operational limits of the distribution grid’s equipment. To meet this goal, the main contributions of this research work consist of proposing two optimization methods to solve the problem. The first one is based on the metaheuristic Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO), and the second one is based on a heuristic algorithm. Both solutions will be applied to different charging situations and their performances will be discussed and compared.

Note that some references mentioned above proposed machine-learning-based methods to solve the problem, as the review paper from18. Machine learning is indeed a very powerful tool for solving optimization problems and has been used in many applications19. Its use in the references above is appropriate, since the focus of the optimization methods is on the distribution network and its performance. However, it is important to mention here that the goal of this paper is to propose very fast charging schedules that use the least amount of data possible. Moreover, the simulation results of “Simulation results” section will demonstrate that metaheuristics and heuristic techniques alone can provide such optimal or very good quality results at very low computational burden. There is no need to rely on past data and training processes, on the contrary, the information needed is related to the moment when there are some vehicles plugged in, the state of charge of their batteries and that the power availability of the grid, as it will become clear on “Mathematical model” section.

This paper is organized as follows. “Mathematical model” section details the mathematical model. “Proposed solution methods” section describes the methods that are used to solve the model. In “Simulation results” section the simulation results are presented and discussed. “Discussion” section is dedicated to discussing and comparing the proposed methods. Finally, the conclusions are shown on “Conclusion” section.

Mathematical model

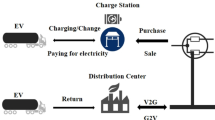

In this work it is assumed that a number of EVs are connected to a charging station, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The charging station (CS) is supplied by a distribution transformer, which is connected to the distribution grid. Assume that a measurement device sends information on the transformer’s available power to the control system. This available power is related to the distribution transformer loading, which can vary throughout the day. Assume also that a second measurement device is also connected to the control system to feed it with information regarding the SOCs of the EVs’ batteries. This information is crucial for the control system to allocate the available power among the connected batteries.

The main constraints associated with the coordination of EVs’ charging refer to (1) the available power from the distribution transformer, and (2) the capacity of the batteries. Violations of these constraints may cause operational problems for the transformer and the distribution grid, as well as the batteries (for example, by affecting their service lives). Additional problems could be high operation costs in case energy consumption occurs during peak hours, or even additional costs related to the demand contract between the utility and the charging station.

On the other hand, assume that the EV owner expects his/her vehicle to be fully charged as fast as possible. Therefore, the EV owner’s expectations and the charging system infrastructure may be conflicting. So, a smart charging coordination system would manage those conflicts in the most efficient way.

The proposed model is based on the following assumptions:

-

The objective function is formulated such that all batteries are fully charged or receive the maximum charge possible within a predefined time interval.

-

Constraints are formulated to consider the power availability of the distribution network, the charging rate of the batteries, their charging efficiencies, the self-discharge rates etc. The model is flexible enough to accommodate additional constraints.

-

The solution to the problem is based on the decision variables, which are defined as the percentage of the power capacity delivered to each battery during each time interval.

Objective function

The objective function is given by

where \(T\) is the number of time periods, \(NV\) is the number of EVs connected to the charging station, \(SO{C}_{i}^{max}\) is the maximum state of charge of vehicle \(i\) (equal to 100%, that is, the battery is fully charged), and \(SO{C}_{i,t}\) is the state of charge of vehicle \(i\) at time period \(t\).

The idea is to minimize \(OF\) to charge the batteries as much and as fast as possible. Note that the higher are the SOCs at any time instant, the smaller is the objective function \(OF\).

Constraints

The constraints are

where \({P}_{i}\) is the power capacity of the battery from EV \(i\), \({x}_{i,t}\) is the percentage of the power capacity delivered to battery \(i\) during time period \(t\), \({P}_{d,t}\) is the available power of the distribution transformer during time period \(t\), \(SO{C}_{i}^{0}\) is the initial state of charge of vehicle \(i\), \({\eta }_{i}\) is the charging efficiency of vehicle \(i\), \({\beta }_{i}\) is the self-discharge rate of vehicle \(i\) (declining state of charge of a battery while the battery is not being used), and \(\Delta t\) is the duration of time period \(t\).

In case the charging station is equipped with a dedicated transformer, the available power \({P}_{d}\) is constant in all time periods. In case the distribution transformer supplies several loads, \({P}_{d}\) varies with time. The simulations shown on “Simulation results” section assume the latter case, which can be more challenging, since the power availability can be low at certain time periods. The methods proposed for the coordination of the charging process must deal with such limitations in the most appropriate way.

Equation (2) limits the power delivered to the batteries in each time interval to the available power of the distribution transformer. This constraint is aimed at guaranteeing that the charging process will not overload the distribution transformer, nor will it violate any operational limit of the grid. Equations (3) and (4) regulate the charging of the batteries based on their respective efficiencies and self-discharge rates, noting that (3) is valid for the first time interval while (4) is valid for the remaining periods. Equation (5) guarantees that the batteries will be charged whenever possible, however, respecting the maximum SOC. Finally, Eq. (6) defines the charging percentage appropriately.

At this point, it is important to point out an important difference between the model (1)-(6) proposed in this paper and the other models proposed in the literature. In7, for instance, the constraints include a more precise model of the distribution grid through the power balance equations, while in this paper the only information available regarding the grid is the available power of the distribution transformer \({P}_{d}\) in each time interval.

Even though the model proposed in this paper seems simpler than the ones existing in7 and other works in the literature, it represents very efficiently a practical and very relevant situation from the standpoint of the charging station. Note that no violations will occur in the grid if the charging procedure is coordinated appropriately to respect \({P}_{d}\). This is all that matters to the charging station, since it has no responsibility for the grid’s operation. The responsibilities associated with the distribution operators are to reinforce transformers and distribution cables and to guarantee an appropriate voltage profile.

On the other hand, the model proposed in7—and other works—is very useful from the standpoint of the distribution utilities. It can be used in planning studies, to predict network reinforcements, such as conductor repowering or transformer replacement. Also, it can be used in operational activities, such as in challenging situations where several vehicles with low SOCs demand a large amount of power which can cause violations in the grid.

Finally, it is important to restate that the main contributions of this paper consist of proposing two solution methods specifically intended to be embedded in the charging station, taking the minimum external information, and quickly establishing a secure charging process without affecting the quality of operation of the distribution grid.

Proposed solution methods

Solution schemes

It is important to note that model (1)-(6) involves a total charging time \({t}^{total}\) divided into \(T\) periods of duration \(\Delta t\), that is

Also, for each period \(t\in [1,T]\) there is an array of unknowns (decision variables) \({X}_{t}\), with \(NV\) elements. Therefore, the total number of unknowns of problem (1)-(6) is \((NV\cdot T)\).

Consequently, problem (1)-(6) can be solved either:

Simultaneously—in this case, the array of decision variables \(X\) has \((NV\cdot T)\) elements—for instance, an \([NV\times T]\) matrix, and all of them are determined after only one run of the selected solution method. For instance, if \(NV=2\) (two vehicles) and \(T=3\) (three periods of time), the decision variable array \(X\) will be

where \({x}_{\text{1,2}}\) is the percentage of the power capacity delivered to battery 1 during time interval 2, and so on and so forth.

Sequentially—the array of decision variables \(X\) has \(NV\) elements—say, a \([NV\times 1]\) vector, and the selected solution method is run \(T\) times for determining all unknowns. For instance, if \(NV=5\) (five vehicles), the decision variable array \(X\) will be

where \({x}_{1}\) is the percentage of the power capacity delivered to battery 1, and so on and so forth.

Solution methods

Teaching–learning-based optimization (TLBO)

Several methods have been proposed for solving non-linear, non-differentiable, hard-to-model, hard-to-solve problems as an alternative to the conventional mathematical programming methods. Metaheuristics are among them. Most metaheuristics have been inspired by the observation of different nature phenomena and behaviors. Examples of nature-based metaheuristics are the ant colony algorithm, artificial bee colony algorithm, bacteria foraging optimization, firefly algorithm, particle swarm algorithm, among others20.

The metaheuristic teaching–learning-based optimization (TLBO) was originally proposed in21. TLBO is a population-based metaheuristic inspired by the interaction of teacher and students in a classroom. The teacher is assumed to be an individual who shares his/her knowledge with the students in the classroom. Also, students learn both with the teacher and among themselves, by collaborating with each other. The level of knowledge of each individual from the population is measured by the respective value of the objective function. The latter is usually known as fitness in other metaheuristics such as the genetic algorithm22 and the artificial immune system23.

TLBO presents many advantages, such as (a) fewer parameters, (b) simple algorithm, (c) easy to understand, (d) fast solution speed, (e) high accuracy, and (f) good convergence ability24.

Unlike other methods proposed in the literature, TLBO does not require problem-dependent parameters to be tuned, which is considered an important advantage of the method. An example of such metaheuristics is the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)25, which requires the tuning of inertia weight factors and acceleration constants. Also, the Firefly Algorithm (FA)26 requires the adjustment of the light absorption coefficient and attractiveness. The Genetic Algorithm (GA) requires the tuning of the mutation rate, the crossover probability, and the selection method21. TLBO does not require any such problem-specific parameters to be tuned24 other than the population size and the number of iterations27, which is a very interesting feature and makes its implementation much simpler.

The algorithm is divided into two phases, namely the “Teacher phase” and the “Student phase”.

Despite its simple structure, there are several versions of TLBO, as discussed in24. It follows the algorithm for TLBO that was used in this paper.

In the algorithm \({N}_{p}\) is the number of individuals of the population. In this case, it corresponds to the charging percentage factors \(x\) for each vehicle and each time interval. In this paper the stopping criterion mentioned in step 6 is simply based on the number of iterations (\(Iter\)).

Both phases of TLBO correspond to greedy procedures, where the existing individuals in the population are replaced by newly generated individuals with superior knowledge (better value for the objective function).

TLBO will be used to solve model (1)-(6) according to both simultaneous (TLBO-Sim) and sequential (TLBO-Seq) schemes.

Heuristic algorithm

Heuristics are methods to solve problems based on experience and/or specific knowledge about their nature. They are specifically intended to be faster than other methods. In the case of optimization problems, one cannot guarantee that a heuristic method will obtain their optimal solutions, however, their solutions are in general very good-quality ones, close enough to the former, as discussed in28.

The heuristic method proposed in this paper is based on using specific knowledge of the EV charging process in a sequential scheme. All features modeled in (1)-(6), such as the state-of-charge of the batteries, the capacity of the charging station itself, the requirement that the batteries must be charged as quickly as possible, among others, are considered appropriately.

The heuristic method for solving the EV charging process is based on the following principles:

-

The charging percentage factor \(x\) of each EV is proportional to its charging needs. In other words, the lower the battery’s SOC is, the higher the charging percentage factor will be.

-

The largest amount of power possible will be supplied to the EVs, respecting the availability of the distribution transformer that supplies the charging station and the vehicles’ needs.

-

The power supplied to each battery is limited to its own capacity of absorbing power within the defined time interval.

-

The battery’s charge is limited to its \(SO{C}^{max}\).

-

In case some batteries are already fully charged, occasional surplus powers are distributed proportionally among the remaining batteries.

For the sake of simplicity, the heuristic method proposed in this paper is divided into two parts, as shown below.

Simulation results

TLBO and the heuristic methods were implemented using GNU Octave version 9.4.0, available at https://octave.org/. The simulations were carried out in a notebook equipped with Intel Core i7-8550U processor, 8 GB RAM, Windows 11 Pro.

Four simulation cases were selected to show the general performances of the three implemented methods, namely:

-

1.

TLBO-Sim – metaheuristic TLBO is run simultaneously for all time intervals.

-

2.

TLBO-Seq – metaheuristic TLBO is run sequentially, each time interval at a time.

-

3.

HEUR – the heuristic method is run sequentially, each time interval at a time.

Also, the features of each method will also be highlighted, discussed, and compared.

Case 1

This case involves eight vehicles connected to the charging station. The vehicles have different states of charge (\(SOC\)), from 0 to 80%, and charging capacities (\(P\)) from 50 to 300 kW. Complete information about this case is shown in Table 1. This is a challenging scenario since the power availability of the distribution transformer (\({P}_{d}\)) is very low most of the time and the SOCs of some vehicles are very low, requiring large amounts of energy. Note that some SOCs are equal to zero, which obviously does not correspond to a practical situation. It is expected that an EV will get to the charging station with some energy left in its battery. The idea here is to push the proposed methods to deal with challenging situations to better evaluate their performances. Note that the proposed model and the proposed solution methods consider the batteries’ self-discharge rates. Each battery has its own rate, as shown in29. For instance, the typical self-discharge rate of a Lithium battery ranges from 5 to 10% per month. Therefore, for the purposes of the problem tackled in this paper, the self-discharge rate \(\beta\) may be considered negligible. In the simulation cases shown here, it will be indeed neglected (\({\beta }_{i}=0)\), however, it was maintained in the model for the sake of completeness. Finally, Table 1 also contains the parameters associated with TLBO, namely the population size \({N}_{p}\) and the number of iterations \(Iter\). Both values were chosen based on extensive simulations, since they basically depend on the particular characteristics of the problem being solved.

Figure 4 shows the charging evolution of all vehicles according to TLBO-Sim, TLBO-Seq and HEUR. Even though there are differences among them, overall, they are very similar. Vehicles with higher initial SOCs are supplied with lower amounts of energy, or even none, while those with lower initial SOCs are supplied with higher amounts of energy. Also, the charging process has been more intense in the last two periods since the available power from the distribution transformer increases.

Of course, the idea of all methods is to use all the power available from the distribution transformer to charge the batteries, but the way this power is distributed among the vehicles varies a little. Note that in the case of TLBO-Seq vehicles 1, 2, and 5 are not supplied with any during the whole period, since they have the higher SOCs. Also, vehicle 4 is only supplied with power in the last two periods, when the power availability increases. So, there is a clear prioritization of the vehicles with the lowest SOCs. Still according to Fig. 4, TLBO-Sim works in a similar manner, however, vehicles 1, 2, 4, and 5 do receive a small amount of energy in the first periods. HEUR presents the most significant differences. Due to its intrinsic principle of proportionality, all vehicles are supplied with some power from the first periods of time on.

The charging behavior associated with vehicle 7 deserves some discussion. Its charging evolutions according to TLBO-Seq and HEUR are similar in general. Small amounts of energy are delivered with time, and larger amounts of energy are delivered in the last two periods of time. Differently, TLBO-Sim basically ignores vehicle 7 most of the time and supplies the battery with energy in the last two periods of time. Despite the differences in the charging evolution, the final SOCs are similar.

Finally, Fig. 5 shows the power balance during the charging procedure for the three proposed methods. The dashed lines show the transformer’s available powers for each time interval, whereas the bars show the powers effectively used to charge the batteries. Considering the limited power available from the distribution transformer and the low SOCs in general, there is no sufficient power to fully charge all batteries within the available charging time. Therefore, all proposed methods demanded all the energy available from the grid and transferred it to the batteries during the whole time.

Case 2

This scenario involves 10 vehicles connected to a charging station. The initial SOCs (\(SO{C}^{0}\)) are in the range [10–50%], and the batteries’ charging capacities (\(P\)) are equal to 20 kW. The availability of the power transformer (\({P}_{d}\)) varies from \(0\) to \(50 \text{kW}\). This case is severe, since it is clearly impossible to fully charge all vehicles in the available time interval. The complete information regarding this simulation is in Table 2.

Figure 6 shows the charging of all vehicles according to TLBO-Sim, TLBO-Seq, and HEUR. The charging patterns for the three methods are similar to Case 1. Note that the final SOCs do not exceed 70% for the three proposed methods, due to the low initial \(SOC\) s and low power availability from the distribution transformer.

Finally, Fig. 7 shows the power balance during the charging procedure. The situation regarding the availability of the distribution transformer during the charging period is similar to Case 1, that is, there was no sufficient power to fully charge all batteries. Once more, all proposed methods demanded all the energy available from the feeding transformer and transferred to the batteries.

Case 3

Case 3 is similar to Case 1, except that 15 time periods were adopted. The additional five periods have full transformer availability (\(P\)), as shown in Table 3 (the differences from Table 1 are in underline, bold face).

Figure 8 shows the charging evolution for all vehicles. Note that all vehicles’ batteries are fully charged at the end of the charging period.

For the sake of simplicity, Fig. 9 shows the power demanded from the transformer during the charging procedure for the heuristic method. In this case, 15 time periods were more than sufficient for all vehicles to be fully charged. In fact, 13 periods were enough, and in the 13th period about 30% of the available power was used to fully charge all vehicles.

Case 4

Case 4 has the basic initial characteristics of Case 3, so its parameters are shown in Table 3. However, in the 10th time interval vehicle 1 leaves the charging spot and another vehicle with a SOC of 10% takes its place. This simulation is intended to show that both the proposed methods TLBO-Seq and HEUR can deal with dynamic and intermittent situations.

Figure 10 shows the charging processes of all vehicles 1 and 6. Note that there was a change of vehicles in the 10th time interval, and that the new vehicle has a 10% initial SOC. This explains the decrease in the \(SOC\).

For the sake of simplicity, Fig. 11 shows the power demanded from the transformer during the charging procedure for the heuristic method. All vehicles were fully charged after 14 time periods. In the 14th period only about 11% of the available power was used to complete the charging process.

Table 4 shows the computational times for all simulation cases. HEUR was clearly the fastest one. The differences between TLBO-Sim and TLBO-Seq for the simulated cases were small from a practical point of view.

Considering that the charging coordination software is embedded in the charging station, it is convenient that the charging process be figured out as fast as possible, and that the customer be informed timely. As the consumer plugs his/her vehicle into the charging station, a message could be sent informing that “After X minutes, the state of charge of the battery will be Y%.” The sooner this message is shown to the consumer the better, to avoid frustration, especially in cases of low availability of the distribution transformer. This also allows him/her to plan and adapt his/her time schedule to the charging process.

Table 5 shows the number of iterations for convergence for the two TLBO schemes. The number of iterations shown in the table are those after which the objective function remained constant, that is, no better solutions have been found afterwards. It is important to note that TLBO was run for 50 iterations, as shown in Tables 1 and 2. Note also that HEUR is not iterative.

The number of iterations of a metaheuristic depends basically on its parameters, on the initial population, and on the random decisions made during the process.

As far as the initial population, TLBO has basically the same characteristics of the several other metaheuristics proposed in the literature, so the size of the population and the initial values associated with each of its individuals affect the performance of the iterative process. In this paper, the size of the population was set based on extensive simulations under several conditions.

TLBO has just one parameter, \({T}_{f}\), differently from other methods, such as the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)25, which requires the inertia weight factors and acceleration constants, the Firefly Algorithm (FA)26, which requires the light absorption coefficient and attractiveness, and the Genetic Algorithm (GA)21, which requires the mutation rate, crossover probability, and the selection method.

Discussion

Some points regarding the characteristics, performances, and usability of the methods proposed in this paper are worth mentioning.

-

The heuristic method was the fastest one in computational terms. However, as mentioned earlier, all simulations were carried out using the software GNU Octave, which is an interpreted language. If the three methods had been implemented in a compiled language, all computer times would have been much smaller. Since the charging coordination program is installed in the charging station, it must be as fast as possible to predict the charging times and to account for changes during the charging process, as the unplugging of a vehicle and the plugging of a new one. Based on the results provided by the heuristic method and shown in this paper, this would be preferred method to be used.

-

All methods provided similar results in terms of the charging processes. The final SOCs were also very close to each other. However, TLBO tended to supply very little or no power at all to those vehicles with larger SOCs. The heuristic method, on the other hand, always distributes the available power among the vehicles proportional to their energy needs. This also implies less power to be supplied to vehicles with larger SOCs; however, all vehicles are supplied with some power at all time periods. From the consumer satisfaction standpoint, it does not seem appropriate that his/her vehicles remain without receiving any power for some periods of time, since this would cause some degree of frustration/anxiety.

-

Despite its very good results, the simultaneous method TLBO-Sim has an implicit disadvantage, considering that in practice the EV charging routine is dynamic and intermittent. In other words, TLBO-Sim works with all time periods simultaneously, and this characteristic is not appropriate for situations where, for instance, a vehicle leaves the charging station at some time interval, even if the charging process was not complete. At the same time, a charging slot that became available may be occupied by another vehicle with a different SOC. Considering these situations, both TLBO-Seq and the heuristic method deal with this problem in a very natural way.

-

It is important to bear in mind that the purpose of this paper is to propose a method that can be embedded in a charging station and be run very efficiently, without minimum interaction with the external world. In this sense, we have accomplished this goal, since the only external information needed is the available power from the grid, or more specifically from the charging station feeding transformer as shown in Fig. 3.

-

Although metaheuristic methods such as TLBO can solve nonconvex problems and obtain good quality solutions, their efficiencies can be improved significantly. The use of some state-of-the-art methods, such as coevolutionary neural solutions for nonconvex optimization30 can effectively reduce the number of iterations, thus reducing the computational cost even further.

Conclusion

In this paper a mathematical model was proposed to represent the objective function and the constraints of a coordinated charging procedure to be carried out in charging stations for EVs. The model was specifically developed based on the charging station point of view, provided that information on the power available from the feeding transformer is available. The transformer’s available power is crucial information to compute the amounts of power transferred to the several batteries that might be connected to the charging station at the same time. At the same time, this information is used so that the charging process will never overload the transformer, so preserving the distribution network.

The coordinated charging model was solved by three methods, namely the metaheuristic TLBO with two versions (decision variables computed either simultaneously or sequentially) and a heuristic method.

The computer simulations showed that all methods were able to provide good-quality solutions to the problem. In particular, the heuristic method obtained those good-quality solutions with much less computational time, as compared to the TLBO. This aspect is very convenient considering that the software would be embedded in a charging station and should provide ready information to the consumers.

As discussed in previous sections, an additional reason for the proposed model to be suited for being embedded in charging stations is that it adapts to the availability of the distribution transformer, therefore, no grid violations will be experienced during the charging process.

The model now will be extended, and more precise information about the grid will be included through the power balance equations and specific constraints regarding current and voltage limits. This new version of the software will in its turn be useful for the distribution utilities since the impact of the presence of several charging stations can be evaluated and grid reinforcements can be devised.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Deloitte. Electric vehicles—Setting a course for 2030. Deloitte Insights (2020). https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/rs/Documents/about-deloitte/DI_Electric-Vehicles.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2023.

Sun, M. et al. Uncovering travel and charging patterns of private electric vehicles with trajectory data: Evidence and policy implications. Transportation 49, 1409–1439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-021-10216-1 (2022).

Clement-Nyns, K., Haesen, E. & Driesen, J. The impact of charging plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on a residential distribution grid. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 25, 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2009.203648 (2010).

Muratori, M. Impact of uncoordinated plug-in electric vehicle charging on residential power demand. Nat. Energy 3, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-017-0074-z (2018).

Verzijlbergh, R. A., Grond, M. O. W., Lukszo, Z., Slootweg, J. G. & Illic, M. D. Network impacts and cost savings of controlled EV charging. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 3, 1203–1212. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2012.2190307 (2012).

Alahyari, A., Pozo, D., Sadri, M. A. Online energy management of electric vehicle parking lots. In 2020 International Conference on Smart Energy Systems and Technologies (SEST) (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/SEST48500.2020.9203421

Sá, S. M., Pereira, M. D., Franco, J. F. Linear programming applied to the coordinated charging of electrical vehicles in distribution systems. Brazilian Congress on Automation (2020). https://doi.org/10.48011/asba.v2i1.1676 (In Portuguese).

Shibi, M., Ismail, L. & Massoud, A. Machine learning-based management of electric vehicles charging: Towards highly dispersed fast chargers. Energies 13, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13205429 (2020).

Tuchnitz, F., Ebell, N., Schlund, J. & Pruckner, M. Development and evaluation of a smart charging strategy for an electric vehicle fleet based on reinforcement learning. Appl. Energy 285(4), 116382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.116382 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Yang, X., Li, B., Cao, B., Li, T. & Zhao, X. Two-level optimal scheduling strategy of electric vehicle charging aggregator based on charging urgency. In 4th International Conference on Smart Power & Internet Energy Systems (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/SPIES55999.2022.10082570

Xiao, J., Wu, N., Han, S., Wu, X. & Gong, W. An orderly charging strategy for multi-type charging stations considering the demand for optimal operation of distribution grids. In 3rd International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Mechatronics Technology (ICEEMT) (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEEMT59522.2023.10263106

Techanoc, S. & Chayakulkheeree, K. Optimal EV charging control for distribution system loss minimization. In International Electrical Engineering Congress (iEECON 2024) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/iEECON60677.2024.10537916

Luan, X. & Guo, Y. Research on EV charging scheduling strategy based on multi-objective optimization. In IEEE 2nd International Conference on Power Science and Technology (ICPST) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPST61417.2024.10602226

Xie, Z., Qi, W., Huang, C. & Li, H. Effect analysis of EV optimal charging on DG integration in distribution network. In IEEE 8th International Conference on Advanced Power System Automation and Protection (APAP) (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/APAP47170.2019.9224720

Lu, X., Liu, N., Chen, Q. & Zhang, J. Multi-objective optimal scheduling of a DC micro-grid consisted of PV system and EV charging station. IEEE Innov. Smart Grid Technol. Asia (ISGT ASIA) https://doi.org/10.1109/ISGT-Asia.2014.6873840 (2014).

Ruan, W., Yu, X., Liu, W., Liu, Z., Yu, Y. & Wu, C. Optimal charging strategy for EVs in microgrid considering customer urgency. In 12th IEEE PES Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC) (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/APPEEC48164.2020.9220439

Lopez. K. L. A machine learning approach for the smart charging of electric vehicles. PhD Dissertation, Université Laval (2019). http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11794/34741. Accessed 22 June 2024.

Shahriar, S., Al-Ali, A. R., Osman, A. H., Dhou, S. & Nijim, M. Machine learning approaches for EV charging behavior: A review. IEEE Access 8, 168980–168993. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3023388 (2020).

Bai, R. et al. Analytics and machine learning in vehicle routing research. Int. J. Prod. Res. 61(1), 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2021.2013566 (2023).

Slowik, A. Swarm Intelligence Algorithms Vol. 1 (CRC Press, 2022).

Rao, R. V., Savsani, V. J. & Vakharia, D. P. Teaching–learning-based optimization: A novel method for constrained mechanical design optimization problems. Comput. Aided Des. 43, 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cad.2010.12.015 (2011).

Holland, J. H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems: An Introductory Analysis with Applications to Biology, Control, and Artificial Intelligence (MIT Press, 1992). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1090.001.0001.

Coelho, G. P., França, F. O. & Von Zuben, F. J. A concentration-based artificial immune network for combinatorial optimization. IEEE Congress Evolut. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1109/CEC.2011.5949758 (2011).

Xue, R. & Wu, Z. A survey of application and classification on teaching–learning-based optimization algorithm. IEEE Access 8, 1062–1079. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2960388 (2019).

Gaing, Z. L. Particle swarm optimization to solving the economic dispatch considering the generator constraints. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 18, 1187–1197. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2003.814889 (2003).

Yang, X. S. Firefly algorithm, stochastic test functions and design optimization. Int. J. Bio-Inspired Comput. 2, 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBIC.2010.032124 (2010).

Rao, R. V. & Patel, V. An elitist teaching-learning-based optimization algorithm for solving complex constrained optimization problems. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Comput. 3(4), 535–560. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijiec.2012.03.007 (2012).

Patnaik, M. & Adrian, A. M. A perspective depiction of heuristics in virtual reality. In Cognitive Big Data Intelligence with a Metaheuristic Approach (eds Mishra, S. et al.) (Academic Press, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-85117-6.00006-6.

Khan, K. A., Hossain, M. A., Obaydullah, A. K. M. & Wadud, M. A. PKL Electrochemical cell and the Peukert’s law. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. Ideas Educ. 4(2), 4219–4227 (2018).

Jin, L., Su, Z., Fu, D.-Y. & Xiao, X.-C. Coevolutionary neural solution for nonconvex optimization with noise tolerance. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 35(12), 17571–17581. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3306374 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported in part by Brazilian funding agency Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) grant 302488/2022-7, and by the Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas, Brazil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B.P.S. and C.A.C. have participated equally in all stages of the research and paper preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This paper does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The authors are aware of and have followed all rules of good scientific practice as stated in the submission guidelines of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Santos, E.B.P., Castro, C.A. Fast charging coordination for electric vehicles in a charging station based on heuristics and metaheuristics. Sci Rep 15, 21031 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06788-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06788-y