Abstract

This study aimed to analyze the prevalence of radix molaris in a subpopulation of Brazil’s Northeast region using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). A total of 1092 CBCT exams and 3315 teeth (1541 first and 1774 s mandibular molars) were analyzed in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes using the PreXion 3D Viewer software. The teeth morphologies were analyzed and the occurrence of radix molaris, location, tooth, type (entomolaris and paramolaris) and patients’ gender were recorded. The data were expressed in the form of absolute and percentage frequencies and statistically analyzed using Pearson’s Chi-square test (P < .05). Fifty-nine patients (5.40%) and 71 teeth (2.14%) presented radix molaris, which was most frequently identified in first mandibular molars (2.92%) than in second mandibular molars (1.47%) (P < .05). No significant differences in the occurrence of radix molaris considering the gender of patients (36 women [5.22%] and 23 men [5.72%)] were observed (P > .05). It was observed that 92.96% of the teeth affected by the anatomical variation studied were classified as radix entomolaris. The bilateral prevalence of radix molaris was approximately 20.34% of the cases involving only first molars (P < .05). The occurrence of radix molaris was higher in first mandibular molars, regardless of the gender of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The scientific and technological advances in the last decades have been responsible for developing new materials, devices, instruments, kinematics, and techniques, which have substantially modified the modus operandi of Endodontics. However, the inability or impossibility of identifying root canals prevents effective processes for cleaning, disinfection, and filling the root canal system (RCS), compromising the main objectives of the endodontic therapy, i.e., to keep or restore the health of periapical tissues1,2.

Previous studies reported difficulties managing different anatomical complexities due to the limited information provided by periapical radiographs3,4. Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) allows multiplanar imaging analyses, favoring more predictable treatment plans and favorable prognoses3,4. CBCT has also been important in providing a more comprehensive understanding of the RCS complexity5,6,7,8.

Permanent mandibular molars are often affected by anatomical variations9. An extra root in these teeth refers to an anatomical variation named radix molaris. When the extra root is located on the lingual surface, it is named radix entomolaris; when the extra root is present on the buccal side, it is referred to as radix paramolaris10. In the studies by Song et al.,11 and Zhang et al.,12 the incidence of radix molaris was higher in Asian and lower in Caucasian populations, respectively. These and other previous research pointed out that race and ethnicity play a fundamental role in the incidence of radix molaris13,14. Hence, more studies are needed to investigate the correlation among these factors in different countries and regions15,16.

Highly populated countries and/or those with large territorial extensions usually present great ethnic and racial heterogeneity17. The greater the population density, territorial extension, and ethnic heterogeneity of a country or geographic region, the greater the difficulties in obtaining reliable samples to accurately determine some population characteristics, such as the anatomy of the RCS. For this reason, different research has been performed to study this variable in subpopulations from the same country, such as Saudi Arabia18,19,20,21, India22,23, and Brazil24,25,26,27. One of the main criticisms regarding studies conducted to investigate the incidence of anatomical variations in subpopulations is that their findings represent only the specific population analyzed. Although this limitation is methodologically valid from a scientific perspective, the relevance of such studies should not be overlooked. Their results can serve as foundational data for future investigations employing more sophisticated methodological designs and rigorous, statistically robust analytical approaches, such as those used in systematic reviews and meta-analyses13,28,29,30,31.

This cross-sectional study investigated the prevalence of radix molaris in mandibular molars from a subpopulation of Brazil’s Northeast region using CBCT exams.

Methods

Ethical approval and informed consent

This study was authorized and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Centro Universitário Christus – UNICHRISTUS, Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil (5.442.892), and it was performed considering the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki “Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects,” (amended in October 2013)32. Informed consent was obtained from each patient or guardian of patients under 18 who participated in the study.

Sample size calculation

The sample size for conducting the current research was calculated based on the number of the subpopulation studied – Brazil’s Northeast region (54.644.582 million people)33. To obtain a 95% confidence interval, the following formula was applied – ([Np(1 − p)]/[(d2 /Z2 1 − α/2*(N − 1) + p*(1 − p)])34,35,36,37, resulting in a minimum sample size of 1025 exams.

Sample selection and image acquisition

Initially, 1420 CBCT exams (909 from women and 511 from men) were randomly screened. These scans were originally performed in the Radiology Department of the Centro Universitário Christus (UNICHRISTUS), Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil, for purposes unrelated to this study, including treatment planning for implant surgery, assessment of tooth impaction, orthodontic therapy, and trauma evaluation.

The images were acquired using a Prexion 3D imaging device (Prexion, Inc., San Mateo, USA) operating at 90 kVp and 4 mA, with a voxel size of 0.125 mm and a slice thickness of 1 mm. According to the evaluators ' necessity, two fields of view (FOV) were used, ranging from 5 × 5 cm to 10 × 10 cm. All scans were conducted following the manufacturer’s guidelines to ensure minimal radiation exposure while maintaining image quality17.

CBCT images were included when they exhibited adequate contrast and density to insure proper visualization of root canal morphologies, and when they featured permanent mandibular first or second molars.

Exclusion criteria comprised the absence of bilateral first and second mandibular molars, incomplete root formation, root resorption, and image artifacts that could hinder the proposed analysis, such as endodontic treatment, crown-bridge prostheses, or intraradicular posts29 So, if a tooth presented a condition that made the analysis difficult, it was excluded. Of the 1420 CBCT examinations initially screened, 328 were excluded. Consequently, the final sample consisted of 1092 exams (690 from women and 402 from men), comprising 3315 teeth (1541 first and 1774 s mandibular molars).

Images analysis

Three endodontists with experience in CBCT analysis underwent a calibration process using 40 standardized CBCT scans, totaling 100 teeth. Each evaluator analyzed 10 scans per session. To minimize fatigue, the calibration was divided into four sessions, with 10 scans assessed per day. The entire process was completed over a 10-day period. Tomography sections were visualized in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes using the PreXion 3D Viewer software (Prexion, Inc., San Mateo, USA) on a Dell Precision T5400 workstation (Dell, Round Rock, TX, USA), with a 17-inch Dell LCD screen with a resolution of 1280 × 1024 pixels, 85 Hz, and 0.255 mm dot pitch operated at 24 bits, in a dark room. Each evaluator analyzed these images twice within a 30-day interval. They were free to adjust the contrast and brightness of the images using the software’s image processing tool to ensure optimum visualization. The long axis of teeth was determined, and images were examined in cross-sections up to the apical third of the root by moving the toolbar from the pulp chamber to the apex. The evaluators were also allowed to manipulate the visualization settings and tools (such as noise reduction or specific filters) to improve the quality of the output image. So, the teeth morphologies were analyzed according to the standard classification of radix molaris.

To ensure methodological consistency and minimize variability associated with evaluator fatigue, the entire sample of 1092 CBCT exams was analyzed using previously established standardized procedures. The dataset was stratified into three subsets of 364 scans each, and three previously calibrated evaluators independently assessed all exams. Each evaluator analyzed 14 scans per day, with mandatory rest intervals every three days to maintain diagnostic accuracy and reduce visual strain. As the evaluation was performed in duplicate, the complete assessment process spanned a period of seven months. All findings, including the presence, classification, and anatomical distribution of radix molaris, were systematically recorded alongside demographic data in a structured Excel database and subsequently subjected to appropriate statistical analyses. Additionally, a comparative table summarizing similar studies in other populations was included to contextualize the present results.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as absolute and percentage frequencies and associated with the classification previously quoted using Pearson’s chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Statistical comparisons were performed according to the side of radix molaris location, tooth, type (entomolaris and paramolaris) and patients gender. SPSS software version 26.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, United States of America) was used to perform the statistical analysis (P < 0.05)34,35,36,37.

Results

Inter- and intra-observer agreement demonstrated Fleiss’ Kappa coefficients of 0.8938 and 0.9039, respectively. The overall inter-observer reliability observed after the definitive image evaluations was similar to that obtained during the calibration process (Fleiss’ Kappa coefficient: 0.87)38. These data support the effectiveness of the calibration process and, consequently, the reliability of the findings obtained in the present study.

The present study analyzed 1092 CBCT exams (690 from women and 402 from men) and 3315 teeth (1541 and 1774 first and second mandibular molars, respectively).

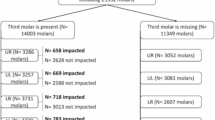

Of the 1092 CBCT exams studied, 59 (5.40%) presented radix molaris (23 men [5.72%] and 36 women [5.22%]) (P > 0.05) and in 1033 exams (94.60%) were no observed radix molaris morphology (Table 1).

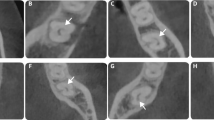

Among the 3315 teeth investigated, 71 (2.14%) presented radix molaris (45 first molars [63.38%] and 26 s molars [36.61%]) (Fig. 1) (P < 0.05) (Table 2). 3244 teeth (97.86%) presented no radix molaris morphology. The prevalence of radix molaris was significantly higher in the first molars (2.92%) compared with the second molars 1.47% (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

No statistically significant differences were identified (P > 0.05) after comparing the prevalence of radix molaris in the two hemiarches (Table 1).

Bilateral radix molaris were only observed in the first molars (P < 0.05) of 12 CBCT exams who presented this characteristic (20.34%) (Fig. 2) (Table 2).

Of the 71 radix molaris, 66 (92.96%) were classified as radix entomolaris and 5 (7.04%) as radix paramolaris (Table 2).

Table 3 shows absolute frequencies and percentages (%) found in studies that evaluated the prevalence of radix molaris in different populations worldwide.

Discussion

Over the years, different methods have been used to study human root canal anatomy, such as radiographs53, longitudinal and cross-sections54,55,56, staining and tooth-clearing techniques57, and the injection of different materials into the root canals, such as silicon, inlay casting wax, and acrylic resin, trying to replicate its internal anatomy58. Although these approaches were instrumental in the past, more modern and accurate techniques have been employed nowadays59,60.

Currently, CBCT is an imaging modality that enables the detailed analysis of internal tooth morphology and represents a significant advancement in Endodontics. Several studies have associated the use of CBCT with improvements in the diagnosis, planning, and execution of endodontic therapies. CBCT imaging is indicated, among other applications, for the investigation and identification of anatomical complexities. However, not all CBCT scans are adequate for detecting subtle anatomical variations, such as radix molaris. Scans obtained with a large field of view (FOV) and larger voxel sizes tend to have reduced sensitivity, making the detection of discrete endodontic anatomical variations less likely. Therefore, to ensure precise diagnosis in Endodontics, the use of CBCT with a small FOV is recommended, as was employed in the present study.

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) is another method that has been used to study numerous matters in Dentistry. Specifically, in Endodontics, it has been employed to investigate root canal anatomy59 and distinct techniques used for removing gutta-percha61, cleaning, shaping62, and filling the root canals63. However, micro-CT cannot be used clinically. Hence, the current study was performed to determine the prevalence of radix molaris in mandibular molars from the Northeast region of Brazil using CBCT exams, considering its potential to be used in vivo, allowing thus the analysis of potential correlations among the anatomical complexity investigated herein and demographic data, such as age and gender60.

The prevalence of radix molaris in the Middle East and European countries ranged from 1.20 to 6.20%43,45 and from 1.67 to 8.60%15,46, respectively. Since in Asiatic countries of Mongoloid origins, such as China, Japan, and Korea, the incidence of radix molaris is greater than 25%, this anatomical feature is no longer considered an anomaly but rather a populational genetic peculiarity12,52. In the studies by Rodrigues et al.,26 and Caputo et al.,24 the prevalence of radix molaris in Brazilian subpopulations (Southeast and Central-West regions) was 2.58% and 2.87% in this order. The higher index found in the current research (5.40%) reiterates the country’s high population heterogeneity.

In the present scientific investigation, the prevalence of radix molaris in the first and second molars was 2.92% and 1.47%, respectively. This finding is in line with previous research conducted in Brazil and other countries12,14,25,30,40,42,49. Our results also rectify a higher prevalence of radix molaris in first mandibular molars12,14,30,40,42. Few studies showed a higher prevalence of radix molaris in second mandibular molars46,51.

A higher prevalence of radix entomolaris (92.96%) than radix paramolaris (7.04%) was also observed herein, which agrees with most previous research, rectifying the supernumerary root on the buccal surface is rare12,30,40,45,46,51. However, Martins et al.49 observed a significantly higher prevalence of radix paramolaris (35.30%) in a Portuguese population. Previous research in Brazilian subpopulations (Southeast and Central-West regions of the country) did not identify radix paramolaris9,26,27. This result may be associated with the Portuguese colonization process that occurred most effectively in the Brazilian Northeast region.

The current findings also showed that although the prevalence of radix molaris has been higher in male patients, no statistically significant differences were identified between genders. Previous studies found similar results15,30,46. However, in the studies by Duman et al.14 and Talabani et al.41, statistical differences were relevant for patients from distinct genders in Turkey and Iraq, respectively.

The major limitation of the present study is that it was performed on a specific region of Brazil using a small sample, considering the country’s population contingent. Nonetheless, developing scientific evidence in Dentistry is a complex and gradual process. The inherent complexity of dental procedures and the multitude of factors and variables capable of influencing their outcomes render dental research particularly challenging64,65. Correlation analyses among the root canal anatomy and demographic data seem even more complex once the heterogeneity of results occurs as a consequence of diverse methodological components, such as sample size, analytical processes, subjective factors potentially capable of influencing the results, and population diversity25. The latter is strongly influenced by the colonization and immigration processes fostered by economic dynamism.

Hence, the findings presented herein, and the results of similar studies should not be dismissed as limited or lacking scientific value. Instead, they contribute to developing more comprehensive and reliable information that extends beyond the investigated populations. This understanding is essential for future research efforts, including studies conducted in randomly chosen countries13,30, across one or more continents29, or globally28. Such research can facilitate simple or complex comparisons, considering the potential influences of various factors, such as demographic and economic conditions, on the anatomy of the RCS. These comparisons can be achieved through well-designed methodologies and advanced statistical approaches, including systematic reviews and meta-analysis31.

Conclusions

The prevalence of radix molaris in the Brazilian subpopulation studied was 5.40% regardless of the gender of the patients. In 20% of cases, radix molaris was present bilaterally only in the first molars, which also had a higher prevalence of the anatomical variation studied than the second molars. Most teeth associated with supernumerary roots (93%) were classified as radix entomolaris.

Data availability

The datasets and the complete statistical analysis of the present research are available and can be requested from the corresponding author.

References

Baruwa, A. O. et al. The influence of missed canals on the prevalence of periapical lesions in endodontically treated teeth: A cross-sectional study. J. Endod. 46, 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2019.10.007 (2020).

Timponi Goes Cruz, A. et al. Cleaning and disinfection of the root canal system provided by four active supplementary irrigation methods. Sci. Rep. 14, 3795. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53375-8 (2024).

Abella, F., Mercade, M., Duran-Sindreu, F. & Roig, M. Managing severe curvature of radix entomolaris: Three-dimensional analysis with cone beam computed tomography. Int. Endod. J. 44, 876–885. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01898.x (2011).

Chan, F., Brown, L. F. & Parashos, P. CBCT in contemporary endodontics. Aust. Dent. J. 68(Suppl 1), S39–S55. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12995 (2023).

Sheth, K., Banga, K. S., Pawar, A., Wahjuningrum, D. A. & Karobari, M. I. Distolingual root prevalence in mandibular first molar and complex root canal morphology in incisors: A CBCT analysis in Indian population. Sci. Rep. 14, 443. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51198-1 (2024).

Aslan, E., Ulusoy, A. C., Baksi, B. G., Mert, A. & Sen, B. H. Cone beam computed tomography evaluation of c-shaped canal morphology in mandibular premolar teeth. Eur. Oral Res. 58, 70–75. https://doi.org/10.26650/eor.20241175997 (2024).

Singh, H., Sroa, R. B. & Mann, J. S. Middle mesial canal incidence and morphology in mandibular first molars: A cone-beam computed tomography and micro-computed tomography evaluation. J. Conserv. Dent. Endod. 27, 897–901. https://doi.org/10.4103/JCDE.JCDE_319_24 (2024).

Nouroloyouni, A., Moradi, N., Salem Milani, A., Noorolouny, S. & Ghoreishi Amin, N. Prevalence and morphology of C-shaped canals in mandibular first and second molars of an Iranian population: A cone-beam computed tomography assessment. Scanning 2023, 5628707. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/5628707 (2023).

Mantovani, V. O. et al. Analysis of the mandibular molars root canals morphology. Study by computed tomography. Braz. Dent. J. 33, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440202205105 (2022).

Carabelli, G. Systematisches Handbuch der Zahnheilkunde 2nd edn. (Braumulle & Seidel, 1844).

Song, J. S. et al. Incidence and relationship of an additional root in the mandibular first permanent molar and primary molars. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 107, e56-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.09.004 (2009).

Zhang, R. et al. Use of cone-beam computed tomography to evaluate root and canal morphology of mandibular molars in Chinese individuals. Int. Endod. J. 44, 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01904.x (2011).

Martins, J. N. R., Gu, Y., Marques, D., Francisco, H. & Carames, J. Differences on the root and root canal morphologies between asian and white ethnic groups analyzed by cone-beam computed tomography. J. Endod. 44, 1096–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2018.04.001 (2018).

Duman, S. B., Duman, S., Bayrakdar, I. S., Yasa, Y. & Gumussoy, I. Evaluation of radix entomolaris in mandibular first and second molars using cone-beam computed tomography and review of the literature. Oral Radiol. 36, 320–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11282-019-00406-0 (2020).

Stamfelj, I., Hitij, T. & Strmsek, L. Radix entomolaris and radix paramolaris: A cone-beam computed tomography study of permanent mandibular molars in a large sample from Slovenia. Arch. Oral Biol. 157, 105842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2023.105842 (2024).

Arman, S. et al. Prevalence of isthmi and root canal configurations in mandibular permanent teeth using cone-beam computed tomography. Biomed. Res. Int. 2024, 9969860. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/9969860 (2024).

Candeiro, G. T. M. et al. Internal configuration of maxillary molars in a subpopulation of Brazil’s Northeast region: A CBCT analysis. Braz. Oral Res. 33, e082. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107bor-2019.vol33.0082 (2019).

Mirza, M. B. Evaluating the internal anatomy of maxillary premolars in an adult Saudi subpopulation using 2 classifications: A CBCT-based retrospective study. Med. Sci. Monit. 30, e943455. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.943455 (2024).

Syed, G. A. et al. CBCT evaluation of root canal morphology of maxillary first premolar in Saudi subpopulation. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci. 16, S1619–S1622. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_1048_23 (2024).

Alshammari, S. M. et al. Prevalence of second root and root canal in mandibular and maxillary premolars based on two classification systems in sub-population of northern region (Saudi Arabia) assessed using cone beam computed tomography (CBCT): A retrospective study. Diagnostics (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13030498 (2023).

Karobari, M. I. et al. Evaluation of root and canal morphology of mandibular premolar amongst Saudi subpopulation using the new system of classification: A CBCT study. BMC Oral Health 23, 291. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03002-1 (2023).

Neelakantan, P., Subbarao, C., Ahuja, R., Subbarao, C. V. & Gutmann, J. L. Cone-beam computed tomography study of root and canal morphology of maxillary first and second molars in an Indian population. J. Endod. 36, 1622–1627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2010.07.006 (2010).

Pawar, A., Thakur, B., Machado, R., Kwak, S. W. & Kim, H. C. An in-vivo cone-beam computed tomography analysis of root and canal morphology of maxillary first permanent molars in an Indian population. Indian J. Dent. Res. 32, 104–109. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_782_19 (2021).

Caputo, B. V. et al. Evaluation of the root canal morphology of molars by using cone-beam computed tomography in a Brazilian population: Part I. J. Endod. 42, 1604–1607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2016.07.026 (2016).

Estrela, C. et al. Study of root canal anatomy in human permanent teeth in a subpopulation of Brazil’s center region using cone-beam computed tomography—Part 1. Braz. Dent. J. 26, 530–536. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440201302448 (2015).

Rodrigues, C. T. et al. Prevalence and morphometric analysis of three-rooted mandibular first molars in a Brazilian subpopulation. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 24, 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-775720150511 (2016).

Silva, E. J., Nejaim, Y., Silva, A. V., Haiter-Neto, F. & Cohenca, N. Evaluation of root canal configuration of mandibular molars in a Brazilian population by using cone-beam computed tomography: An in vivo study. J. Endod. 39, 849–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2013.04.030 (2013).

Martins, J. N. R. et al. Worldwide assessment of the mandibular first molar second distal root and root canal: A cross-sectional study with meta-analysis. J. Endod. 48, 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2021.11.009 (2022).

Hatipoglu, F. P. et al. Assessment of the prevalence of radix entomolaris and distolingual canal in mandibular first molars in 15 countries: A multinational cross-sectional study with meta-analysis. J. Endod. 49, 1308–1318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2023.06.011 (2023).

Torres, A. et al. Characterization of mandibular molar root and canal morphology using cone beam computed tomography and its variability in Belgian and Chilean population samples. Imaging Sci. Dent. 45, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.5624/isd.2015.45.2.95 (2015).

Prott, L. S., Carrasco-Labra, A., Gierthmuehlen, P. C. & Blatz, M. B. How to conduct and publish systematic reviews and meta-analyses in dentistry. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.13366 (2024).

General Assembly of the World Medical, A. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J. Am. Coll. Dent. 81, 14–18 (2014).

https://mundoeducacao.uol.com.br/geografia/censo-demografico.htm.

Büttner, P. & Muller, R. Epidemiology (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Chow, S.-C., Shao, J. & Wang, H. Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research 2nd edn. (Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2008).

Hirsch, R. P. & Poneleit, K. M. Biostatistical Applications in Health Research (Stat-Aid, 2008).

Looney, S. W. Biostatistical Methods (Humana Press, 2002).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174 (1977).

McHugh, M. L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. (Zagreb) 22, 276–282 (2012).

Alazemi, H. S., Al-Nazhan, S. A. & Aldosimani, M. A. Root and root canal morphology of permanent mandibular first and second molars in a Kuwaiti population: A retrospective cone-beam computed tomography study. Saudi Dent. J. 35, 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sdentj.2023.03.008 (2023).

Talabani, R. M., Abdalrahman, K. O., Abdul, R. J., Babarasul, D. O. & Hilmi Kazzaz, S. Evaluation of radix entomolaris and middle mesial canal in mandibular permanent first molars in an Iraqi subpopulation using cone-beam computed tomography. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 7825948. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7825948 (2022).

Hiran-Us, S. et al. Prevalence of C-shaped canals and three-rooted mandibular molars using CBCT in a selected Thai population. Iran. Endod. J. 16, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.22037/iej.v16i2.30527 (2021).

Senan, E., Alhadainy, H. & Madfa, A. A. Root and canal morphology of mandibular second molars in a Yemeni population: A cone-beam computed tomography. Eur. Endod. J. 6, 72–81. https://doi.org/10.14744/eej.2020.94695 (2021).

Qiao, X. et al. Prevalence of middle mesial canal and radix entomolaris of mandibular first permanent molars in a western Chinese population: An in vivo cone-beam computed tomographic study. BMC Oral Health 20, 224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-020-01218-z (2020).

Al-Alawi, H. et al. The prevalence of radix molaris in the mandibular first molars of a Saudi subpopulation based on cone-beam computed tomography. Restor. Dent. Endod. 45, e1. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2020.45.e1 (2020).

Kantilieraki, E., Delantoni, A., Angelopoulos, C. & Beltes, P. Evaluation of root and root canal morphology of mandibular first and second molars in a Greek population: A CBCT study. Eur. Endod. J. 4, 62–68. https://doi.org/10.14744/eej.2019.19480 (2019).

Razumova, S. et al. A cone-beam computed tomography scanning of the root canal system of permanent teeth among the Moscow population. Int. J. Dent. 2018, 2615746. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2615746 (2018).

Gupta, A., Duhan, J. & Wadhwa, J. Prevalence of three rooted permanent mandibular first molars in Haryana (North Indian) population. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 8, 38–41. https://doi.org/10.4103/ccd.ccd_699_16 (2017).

Martins, J. N. R., Marques, D., Mata, A. & Carames, J. Root and root canal morphology of the permanent dentition in a Caucasian population: A cone-beam computed tomography study. Int. Endod. J. 50, 1013–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.12724 (2017).

Monsarrat, P. et al. Interrelationships in the variability of root canal anatomy among the permanent teeth: A full-mouth approach by cone-beam CT. PLoS ONE 11, e0165329. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165329 (2016).

Demirbuga, S., Sekerci, A. E., Dincer, A. N., Cayabatmaz, M. & Zorba, Y. O. Use of cone-beam computed tomography to evaluate root and canal morphology of mandibular first and second molars in Turkish individuals. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 18, e737-744. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.18473 (2013).

Kim, S. Y., Kim, B. S., Woo, J. & Kim, Y. Morphology of mandibular first molars analyzed by cone-beam computed tomography in a Korean population: Variations in the number of roots and canals. J. Endod. 39, 1516–1521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2013.08.015 (2013).

Laurichesse, J. M., Chapelle, P. & Griveau, B. Root canal anatomy and its radiographic interpretation. Actual. Odontostomatol. (Paris) 7, 97–136 (1977).

Artal, N. & Gani, O. Endodontic anatomy of the root canals of lower incisors. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 13, 39–49 (2000).

Geider, P., Perrin, C. & Fontaine, M. Endodontic anatomy of lower premolars–apropos of 669 cases. J. Odontol. Conserv. 10, 11–15 (1989).

Gulla, R., Riitano, G. & Riitano, F. Study of canal anatomy using longitudinal sections, castings and diaphanization. G. Endod. 4, 11–16 (1990).

Vertucci, F. J. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 58, 589–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(84)90085-9 (1984).

Sultana, A., Rahman, M. M., Rahman, M. M. & Shrestha, P. Reproduction of intra-radicular surface anatomy of extracted human teeth: Comparison of three different materials using injection technique. Mymensingh Med. J. 19, 181–184 (2010).

Al-Rammahi, H. M., Chai, W. L., Nabhan, M. S. & Ahmed, H. M. A. Root and canal anatomy of mandibular first molars using micro-computed tomography: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health 23, 339. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03036-5 (2023).

Candeiro, G. T. M., Monteiro Dodt Teixeira, I. M., Olimpio Barbosa, D. A., Vivacqua-Gomes, N. & Alves, F. R. F. Vertucci’s root canal configuration of 14,413 mandibular anterior teeth in a Brazilian population: A prevalence study using cone-beam computed tomography. J. Endod. 47, 404–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2020.12.001 (2021).

Santos-Junior, A. O. et al. Flatsonic ultrasonic tip optimizes the removal of remaining filling material in flattened root canals: A micro-computed tomographic analysis. J. Endod. 50, 612–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2024.01.011 (2024).

Zhu, Q. et al. Micro-computed tomographic evaluation of the shaping ability of three nickel-titanium rotary systems in the middle mesial canal of mandibular first molars: An ex vivo study based on 3D printed tooth replicas. BMC Oral Health 24, 294. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04024-z (2024).

Shantiaee, Y., Zandi, B., Hosseini, M., Davoudi, P. & Farajollahi, M. Quality of root canal filling in curved canals utilizing warm vertical compaction and two different single cone techniques: A three-dimensional micro-computed tomography study. J. Dent. (Shiraz) 25, 147–154. https://doi.org/10.30476/dentjods.2023.98119.2054 (2024).

Alim-Uysal, B. A., Goker-Kamali, S. & Machado, R. Difficulties experienced by endodontics researchers in conducting studies and writing papers. Restor. Dent. Endod. 47, e20. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2022.47.e20 (2022).

Neuppmann Feres, M. F. et al. Barriers involved in the application of evidence-based dentistry principles: A systematic review. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 151, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2019.08.011 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M.A.O.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, and writing (original draft preparation). M.C.M.G and M.F.S.N.: methodology, data curation and writing (original draft preparation). R.M.: writing (review and editing). D.M.M.: data curation, supervision and writing (review and editing). H.C.P.: supervision and writing (review and editing). G.T.M.C.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, statistical analysis, supervision, and writing (review and editing). All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martins Araújo de Oliveira, Y., Mendes Gomes, M.C., Nascimento, M.F.S. et al. Prevalence of radix molaris in mandibular molars of a subpopulation of Brazil’s Northeast region: a cross-sectional CBCT study. Sci Rep 15, 22651 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06790-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06790-4