Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) is a predominant etiological agent of nosocomial infections. This research examined the efficacy of rutin encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles (Rut-CS) in inhibiting the proliferation of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa and diminishing biofilm formation. SEM, DLS and FTIR analyzed the nanoparticles to ascertain their shape. The antibacterial activity was evaluated using agar well diffusion. The findings indicated that Rut-CS nanoparticles had considerable antibacterial efficacy and substantially reduced the expression of critical biofilm-associated genes, lasR and AlgD. The Rut-CS nanoparticles exhibited no toxicity to human dermal fibroblast (HDF) cells at the minimal inhibitory dose. The data indicate that Rut-CS nanoparticles may serve as a viable technique to address highly resistant P. aeruginosa infections, facilitating novel antibacterial research methodologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) is a predominant etiological agent of nosocomial diseases, accounting for 10% of the total hospital-acquired illnesses1. Infections generated by P. aeruginosa can be serious and potentially fatal. Treatment challenges arise due to its limited sensitivity to antimicrobial drugs and a high incidence of resistance to antibiotics throughout treatment, leading to significant poor consequences2. Resistance to antibiotics is becoming a bigger issue in P. aeruginosa3. Increased resistance to medications arises from the de novo development of tolerance in a particular organism after antibacterial exposure and from the transmission of organisms with resistance across individuals. The development of resistance following exposure to several medications and cross-resistance among drugs may lead to multidrug-resistant (MDR) P. aeruginosa4. In light of this escalating danger, research has increasingly concentrated on investigating natural substances with intrinsic antimicrobial capabilities as possible replacements or supplements to traditional antibiotics5. Although many antibacterial drugs exist on the medical market, continued study on effective antimicrobial substances, particularly those with innovative techniques, is essential. This is crucial to avert the development of resistance to current antibacterial drugs and offer adequate treatment alternatives for antibiotic-resistant diseases5. Historically, conventional medicine has depended on medicinal herbs. Natural chemicals such as thymol, quercetin, and rutin (Rut) have attracted interest because of their affordability, protection, and effectiveness as medicines6.

The flavanols class includes the greenish-yellow powder known as rutin, which was discovered for the first time in 18427. Studies indicate that rutin is found in more than 70 plant species, with grapes and buckwheat exhibiting the most significant amounts of rutin relative to other taxa. Rutin is primarily discovered in the Phyllanthus emblica L. species8. The constituents of P. emblica fruits mainly include tannins, flavonoids, and other phytochemicals. The presence of tannins in P. emblica fruit is believed to contribute to the stability of vitamin C. These phytochemicals increase antioxidant capability and efficiently neutralize free radicals. Rutin is a phytochemical present in some fruits and vegetables. P. emblica and Eucalyptus serve as sources of rutin9. The many health advantages of rutin to people have been acknowledged, such as its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects. Rutin has shown that it protects neurons against cerebral ischemia10. The intravenous injection of rutin resulted in the reduction of ischemic brain apoptosis by inhibiting p53 gene expression and lipid peroxidation while simultaneously increasing endogenous antioxidant defense enzymes11. Rutin has anticonvulsant properties and appears to be harmless for individuals with epilepsy since it does not interfere with the efficacy of prescribed antiepileptic medications nor have any adverse reactions. Furthermore, rutin has demonstrated antibacterial efficacy versus other bacterial species, notably P. aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli10,11,12. Rutin has shown antibacterial effectiveness against many bacterial species, including P. aeruginosa and Escherichia coli, perhaps via mechanisms such as K + leakage12.

Rutin can suppress the prooxidant actions of some flavonoids. Another benefit of rutin, distinguishing it from other flavonoids like apigenin, is its lack of cytotoxicity against cells that are normal in humans13. Consequently, the harmless and non-oxidizing properties of rutin allow it to be a very efficient compound14. The primary limitation of rutin is its restricted solubility in aquatic environments, resulting in reduced bioavailability15. To overcome this constraint, polymeric nanoparticles, namely chitosan nanoparticles (CS NPs), have emerged as attractive drug delivery vehicles owing to their biocompatibility, mucoadhesive characteristics, and capacity to improve the solubility and bioavailability of hydrophobic chemicals such as rutin. Inadequate bioavailability is a common problem seen in several natural substances, including apigenin15. Polymeric nanoparticles have been extensively studied as nano-formulations to improve the bioavailability of flavonoids16.

The organic cationic polysaccharide chitosan (CS) is made up of N-acetylglucosamine and glucosamine molecules connected by β-(1–4) glycosidic bonds. The second most common polymer in nature, chitin, is deacetylated to produce it17. Chitosan is often derived from the shells of crustaceans (including shrimp, crabs, and lobsters), the exoskeletons of insects, and the cell walls of fungi18. The distinctive properties of chitosan, comprising biocompatibility, nontoxic nature, and minimal immunogenicity, enable its extensive use across diverse sectors such as medicine delivery, biological sciences, and food processing. Furthermore, CS has significant antimicrobial properties versus a wide range of pathogens, including both Gram-positive and Gram-negative microorganisms19.

Moreover, the mucoadhesive characteristics and the capacity to disrupt cell-to-cell tight connections of CS NPs enable them to adhere to mucosal membranes and progressively deliver the encapsulated drug via oral and vaginal pathways. These beneficial characteristics provide CS an attractive option for encapsulating antimicrobial medication and formulating novel nano-therapeutics to treat microbial illnesses20. Prior investigations have effectively encapsulated diverse polyphenols with antimicrobial characteristics, including thymol, employing chitosan nanoparticles18,19,20. However, the effects of rutin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles (Rut-CS) on P. aeruginosa remain unexamined at this point. To address the current lack of information regarding the potential of rutin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles against P. aeruginosa, this research aimed to produce Rut-CS nanoparticles and comprehensively evaluate their antimicrobial and antibiofilm efficacy against this significant pathogen.

Experimental

Materials and chemicals

Low molecular mass chitosan (30–100 cP, 1 wt% in 1% acetic acid at 25 °C) and rutin (purity > 97.0%) were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich. Pentasodium triphosphate (TPP) and glutaraldehyde (purity > 98.0%) were procured from Merck. The phosphate buffer solution (PBS), sodium hydroxide, deionized water, Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and chloroform was purchased from Merck (Germany). Trypan blue, Medium RPMI-1640, Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), and penicillin/streptomycin 100X were purchased from Gibco (USA). Mueller Hinton Agar, Nutrient agar, Nutrient broth, and Eosin methylene blue (EMB) agar were obtained from ZistYar Sanat Company (ZYS, Iran; https://zys-group.ir/). Synthesis of primers and RNA extraction kit was obtained from Sinaclon (Iran) and cDNA synthesis kit was obtained from Yekta Tajhiz (Yekta Tajhiz, Iran). All analytical grade compounds were readily accessible for purchase.

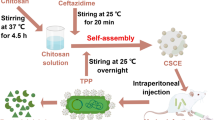

Preparation of rutin encapsulated Chitosan (RUT-CS) nanoparticles

The synthesis of Rut-CS was conducted using the ionic gelation method. CS powder (1 g) was solubilized in a 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution (5 ml) with continuous magnetic stirring for 24 h to produce 0.2 g/ml CS solution. Subsequently, 1 g of Rut powder was incorporated into 5 ml of Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) while under magnetic stirring to produce 0.2 g/ml Rut solution. The resultant clear 0.2 g/ml chitosan solution (5 ml) was mixed with 0.2 g/ml Rut solution (5 ml) to achieve a final concentration of 200 mg/mL RUT-CS solution. Sodium hydroxide (2 M) was subsequently added to bring the pH down to 5. The TPP mixture (0.1%, w/v) was produced by dispersing it in deionized water for one minute. The TPP was thereafter introduced dropwise to the Rut-CS solution at a 1:3 (v/v) ratio while maintaining continuous stirring at 400 rpm. After 1 h of stirring, the resultant milky colloidal solution was centrifuged at 5000 g for 20 min at 4˚C. The supernatant was removed, and the resulting pellet was rinsed with deionized water to remove unattached Rut. The pellet was suspended in deionized water and the resultant solution was subjected to sonication using a probe sonicator at 80% power and a temperature of 10 °C for 8 min. The final solution was frozen at − 40 ˚C overnight. Thereafter, Rut-CS NPs were preserved at 4˚C for additional analysis.

Characterization of Rut-CS nanoparticles

Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

DLS investigation was used to evaluate the distribution of sizes of the Rut-CS nanoparticles. The Rut-CS Nanoparticles were first suspended in water, and a tiny aliquot of this solution was introduced into the cuvette of the ZetaPals device (Brookhaven Instruments Corp., USA). The observations were conducted at an angle of scattered light of 90° and a temperature of 25 °C. All characterization tests of Rut-CS nanoparticles were performed by the ZistYar Sanat Company (ZYS, Iran; https://zys-group.ir/) located in Iran.

Zeta potential

The Rut-CS Nanoparticles’ surface electrical charge was measured using the Nicomp® Nano ZLS System (Entegris, USA). The particles underwent ultrasound treatment after being suspended in 50% glycerol, to put it briefly. The suspension of samples was next moved to a zeta-potential cell, where investigations were conducted at an electrode voltage of 3.4. All characterization studies of Rut-CS nanoparticles were conducted at the ZistYar Sanat Company (ZYS, Iran; https://zys-group.ir/) in Iran.

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (Fe-SEM)

The dimensions and shape of the Rut-CS nanoparticles were analyzed utilizing field emission scanning electron microscopy (Fe-SEM). The Rut-CS nanoparticles were dispersed in ethanol using sonication. Subsequently, the particles were affixed to a graphite tab and coated with a tiny coating of gold. Subsequently, Fe-SEM scanning was performed utilizing a MIRA3 TESCAN microscope (Czech Republic) at a voltage of 15 kV. Furthermore, ImageJ software was used to examine Fe-SEM pictures. All characterization tests of Rut-CS nanoparticles were performed by the ZistYar Sanat Company (ZYS, Iran; https://zys-group.ir/) located in Iran.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The materials were analyzed using FTIR and Thermo Nicolet Avatar 360 equipment (USA) to ascertain their functional groups. The samples were combined with a solution of potassium bromide (KBr) and placed under vacuum to eliminate air. The powdered specimens were then compacted into pellets utilizing a press, and the pellets’ spectra were obtained throughout the wavelength spectrum of 500–4000 cm − 1 at an ambient temperature of 25–35 °C. All characterization tests of Rut-CS nanoparticles were performed by the ZistYar Sanat Company (ZYS, Iran; https://zys-group.ir/) located in Iran.

In vitro drug release study

The drug was administered in a controlled environment employing a dialysis bag containing an average molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of 12 kDa. To accomplish this goal, the dialysis bag included 2 mL of rutin and RUT-CS. The whole combination was submerged in a 50 mL PBS solution with a pH of 7.4. The resultant mixture was meticulously agitated at 37 °C at 50 rpm. Thereafter, it was partitioned into equal segments at certain intervals, and a new environment was established. Additionally, the same procedure was performed for the unbound rutin. This method was employed to assess the release of several RUT-CS formulations. Measurements were obtained at intervals from 0 to 120 h.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

P. aeruginosa obtained from ZistYar Sanat Company was defined as PA-ZYS. PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS02, and PA-ZYS03 were the pathogenic strains of P. aeruginosa that were acquired from ZistYar Sanat Company (ZYS, Iran). Furthermore, P. aeruginosa ATCC 12,453 was used as a reference strain. The bacterial strains were cultured on nutrient agar at 37 °C for 24 h. A single colony from each culture of bacteria was inoculated into Nutrient broth and cultured under ideal growth conditions.

Well diffusion method

The antibacterial effectiveness of Rut-CS nanoparticles versus P. aeruginosa was evaluated utilizing a well diffusion experiment. P. aeruginosa with a 0.5 McFarland density was cultivated on the Muller Hinton Agar (MHA). A sterilized 6-mm cork-borer was used to bore four 6-mm wells into the inoculated media. Each well was loaded with 80 µl of Rut-CS, Rut, CS, and PBS. The solution was allowed to be distributed for approximately 20 min at room temperature and thereafter incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the plates were assessed for a clear zone of inhibition around the well, demonstrating the antibacterial effectiveness of the tested drugs. The zone of inhibition (ZOI) for bacterial growth was visually assessed and measured in millimeters (mm).

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of Rut and Rut-CS nanoparticles versus P. aeruginosa pathogens was identified utilizing the broth micro-dilution method. Initially, different concentrations of Rut and Rut-CS NPs (from 0.195 to 200 mg/mL) were allocated in a 96-well microtiter plate assay (MPA). Then, colonies of overnight cultured P. aeruginosa strains were inoculated in the nutrient broth (NB) media. The 100µL of the 0.5 McFarland density microbial culture was introduced into each well. The microtiter plates were incubated at 37 ˚C for 24 h and then assessed for bacterial growth. The minimum concentration of Rut and Rut-CS nanoparticles that suppressed bacterial growth was chosen as the MIC value. The well after the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) that exhibits no turbidity is designated as the Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC).

Anti-biofilm formation assay

The crystal violet labeling experiment was used to evaluate the impact of Rut and Rut-CS NPs on the development of biofilms in P. aeruginosa strains. First, 96-well plates were used to cultivate bacterial cells with ½ MIC of Rut and Rut-CS Nanoparticles. The media harboring non-adherent cells was extracted after a 48-hour incubation period, and the plate was then rinsed three times with distilled water. Subsequently, the wells were allowed to air-dry, after which a 0.1% crystal violet mixture was introduced to each well and incubated for 30 min. Subsequently, the surplus color was removed, and the plate was rinsed with distilled water. The amount of biofilm development was assessed by measuring the optical density at 570 nm after 30% acetic acid was introduced to solubilize the colorant. The wells devoid of bacterial cells served as negative controls, while the untreated cells served as positive controls.

Biofilm genes transcription analysis

Quantitative Real-Time PCR was used to evaluate the impact of PBS, Rut, and Rut-CS nanoparticles on the transcription of the lasR and AlgD biofilm genes in the P. aeruginosa strain. After samples were treated with sub-MIC amounts of Rut, and Rut-CS nanoparticles, the total RNA was extracted utilizing a total RNX-Plus kit. cDNA synthesis was conducted using the YTA Kit Protocol (Yekta Tajhiz; https://yektatajhiz.com/wp-content/uploads/Protocol-of-cDNA-Synthesis-Kit-yektatajhiz.pdf). A real-time PCR experiment was conducted using the YTA SYBR Green master mix (Yekta Tajhiz). For Real Time-PCR, 15 µL of the reaction was generated. The whole volume included 1µL of cDNA, 0.5 µL of forward primer, 0.5 µL of reverse primer, 7.5 µL of master mix, and 5.5 µL of water. The temperature-dependent cycling protocol included an initial denaturation phase at 95 °C for 8 min, afterward 45 cycles at 95 °C for 40 s and 58 °C for 40 s. The sequences of primers for the lasR and AlgD genes, as well as 16 S rRNA, are shown in Table 1.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of CS, Rut, and Rut-CS nanoparticles was assessed using the MTT colorimetric analysis. 2 × 105 healthy human dermal fibroblast (HDF) cells were grown in 96-well plates using RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The plates were then positioned in a CO2 incubator and maintained at a temperature of 37 °C. The cells were exposed to CS, Rut, and Rut-CS nanoparticles at MIC dose. Following the incubation process, 20 µL of the MTT solution (5 mg/mL) in PBS was dispensed into each well. Following a 4-hour incubation, the solution was removed, and 100 mL of DMSO was introduced to the 96-well plates. The plates were stirred at 400 rpm for 5 minutes to disintegrate the formazan crystals formed in DMSO completely. The color intensity was quantified using an ELISA Reader Stat Fax2100 at an absorbance of 570 nm. Cell viability was measured as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3). HDF cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium devoid of the test material as a control. The ratio of cell viability was determined utilizing the Eq. 1:

Statistical analysis

The findings were presented as mean ± SD, and the investigations were conducted in triplicate. GraphPad Prism 9 software was used to do a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate the distinctions among the control and treatment groups. P-values less than 0.05 were deemed significant.

Results and discussion

Size and ZP measurements of the nanoparticles

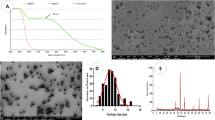

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) corroborated these results, revealing typical dimensions of 300 nm. FESEM images (Fig. 1A) exhibited a mainly spherical shape with uniform dispersion of nanoparticles within the nanometer scale. The mean particle size (MPS) study indicated diameters of 501 nm for Rut-CS (Fig. 1B). The examination of particle size distribution corroborated the identified size ranges. Zeta potential (ZP) measurements produced positive values of 31.63. Table 2 presents further information about the morphological attributes of both nanoparticle varieties.

Fourier transform infra-red (FT-IR) analysis

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Fig. 1C) identified distinct peaks for Free Rutin and Rut-CS nanoparticles. Free Rutin exhibited distinct peaks at 630 and 1585 cm-1 (amide I band) and a broad band ranging from 3186 to 3630 cm-1, which is attributed to O-H stretching vibrations. Rut-CS showed significant peaks at 3610 cm-1 (O-H stretching). Furthermore, peaks at 646 cm-1, 2362 cm-1 (amide II band), 2908 cm-1 (C-H stretching), and 1036 cm-1 (C-O stretching) were detected. Rut-CS nanoparticles displayed peaks at 2362 cm-1, likely signifying –NH3 + interactions inside the CS. The detection of a signal at 646 cm-1 further corroborated the presence of –NH3 + groups. Significantly, several peaks identified in Rut-CS closely resembled those present in Free Rutin, indicating effective integration of Free Rutin into the nanoparticle structure.

In-vitro drug release.

This study aimed to examine the effect of CS on Rutin’s release patterns. Figure 1D depicts the drug release profiles from the dialysis bag containing the Rutin and RUT-CS nanoparticles. Figure 1D illustrates that the encapsulation of Rutin in chitosan efficiently inhibits burst emission. The Rutin release profile had an initial quick-release stage that lasted up to 6 h, followed by a prolonged delayed release stage of up to 120 h. Figure 1D indicates that 88.5% of free Rutin is released during the first 6 h. The release stays constant thereafter, with 100% of the Rutin released within 80 h. The drug release rate in the RUT-CS nanoparticles is 65% over 80 h, increasing to 84.5% after 120 h.

(A) The appearance and size of produced Rut-CS nanoparticles were measured using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FeSEM). (B) Quantifying the size dispersion of Rut-CS nanoparticles by DLS analysis. (C) Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra of Free rutin and Rut-CS nanoparticles. (D) In-vitro drug release; The drug release rate in the RUT-CS nanoparticles is 65% over 80 h, increasing to 84.5% after 120 h.

Well diffusion results

The agar well diffusion assay was utilized to evaluate the antimicrobial effectiveness of Rut-CS nanoparticles against several strains of P. aeruginosa. The findings demonstrated a significant inhibitory impact of Rut-CS NPs, but CS and PBS alone did not generate any inhibition zones. Rut-CS NPs established a growth inhibition zone of between 18 and 21 mm. The sizes of the inhibitory zones created by Rut-CS Nanoparticles versus P. aeruginosa are shown in Fig. 2. The Rut-CS Nanoparticles showed the most significant action against PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS02, and PA-ZYS03, with inhibition zones of over 18 mm, 21 mm, and 19 mm, respectively. The zone of inhibition (mm) for free rutin was 8 mm, 12 mm, and 10 mm against PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS02, and PA-ZYS03, indicating the lowest degree of activity in comparison to Rut-CS Nanoparticles. Chitosan and PBS did not have antibacterial properties, so the interval was defined between 0 and 1 mm (Fig. 2).

MIC and MBC value of free rutin and Rut-CS nanoparticles

The microdilution technique was employed to assess the inhibitory impact of Rut-CS nanoparticles on P. aeruginosa strains. The MIC values of Rut-CS NPs for the P. aeruginosa strains ATCC12453, PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS02, and PA-ZYS03 were documented at 1.56 mg/mL. The Rut-CS NPs suppressed the development of P. aeruginosa strains ATCC12453, PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS02, and PA-ZYS03 at a dose of 3.125 mg/mL. The MIC and MBC values for all four bacterial strains treated with Free Rutin were 12.5 mg/mL and 25 mg/mL, respectively (Table 3).

Biofilm formation and anti-biofilm assay

The results of the Congo Red Agar test showed that all 4 strains (ATCC12453, PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS02, and PA-ZYS03) had the ability to form biofilm (Fig. 3). The data indicate that PA-ZYS02 strains exhibiting an optical density of 0.287 formed intermediate biofilms after treatment with Rut-CS nanoparticles, whereas PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS03, and ATCC12453 created poor biofilms with scores of 0.138, 0.102, and 0.089, respectively. PA-ZYS02 formed a robust biofilm with an optical density score of 0.436 after treatment with Free Rutin, whereas PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS03, and ATCC12453 strains exhibited modest biofilm formation with optical density scores of 0.195, 0.132, and 0.143, respectively (Table 4).

Relative transcription of biofilm genes

After administering treatments to P. aeruginosa strains, the messenger RNA (mRNA) concentrations for biofilm-related genes (lasR and AlgD) were analyzed by Real-Time PCR to validate the efficacy of PBS, Free Rutin and Rut-CS nanoparticles in inhibiting bacterial biofilm gene expression. The results indicate that relative to the PBS group and Free Rutin, the mRNA levels of lasR and AlgD were significantly decreased after treatment with Rut-CS nanoparticles. The mRNA levels of lasR in the PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS02, PA-ZYS03, and ATCC12453 strains were measured at 0.87, 0.75, 0.81, and 0.70, respectively, after treatment with Rut-CS nanoparticles. The mRNA levels of lasR in the PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS02, PA-ZYS03, and ATCC12453 strains were 2, 2.82, 1.41, and 1.62, respectively, after treatment with Free Rutin. The mRNA levels of AlgD in the PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS02, PA-ZYS03, and ATCC12453 strains were quantified at 0.65, 0.85, 0.88, and 0.80, respectively, after incubation with Rut-CS nanoparticles. The mRNA levels of AlgD in the PA-ZYS01, PA-ZYS02, PA-ZYS03, and ATCC12453 strains were 1.74, 1.31, 1.51, and 1.27, respectively, after incubation with Free Rutin. This indicates that P. aeruginosa strains are vulnerable to the antibacterial effects of Rut-CS nanoparticles (Fig. 4).

The impact of PBS, free rutin, and Rut-CS nanoparticles on the transcription of (A) lasR and (B) AlgD biofilm genes. The presented statistics represent the mean value ± standard deviation (SD) derived from three distinct and independent research. The significance thresholds were defined as **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05.

Cytotoxicity assay

This study compared the cytotoxicity of free rutin and rutin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles (Rut-CS) on HDF cells. Rut-CS nanoparticles showed significantly lower toxicity than free rutin at all tested concentrations. After 24, 48, and 72 h of exposure to the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of free rutin (12.5 mg/ml), approximately 67%, 61%, and 56% of cells remained viable. In contrast, when treated with the MIC of Rut-CS nanoparticles (1.56 mg/ml), cell viability remained high at 93%, 89%, and 88% after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively (Fig. 5).

Discussion

P. aeruginosa is a significant nosocomial infection, often demonstrating antibiotic resistance and complicating treatment approaches22. The growing issue of antibiotic resistance requires the investigation of new antimicrobial agents and strategies, with effective phytochemicals being a viable option23. In accordance with this, our work examined the effectiveness of rutin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles (Rut-CS) against P. aeruginosa. Previous research has documented the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of various plant-derived polyphenols, including curcumin and baicalin24,25, and specifically rutin against several pathogens such as P. aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus26,27. Our findings corroborate these observations by demonstrating significant antibacterial and antibiofilm effects of Rut-CS nanoparticles against P. aeruginosa strains. Furthermore, our investigation into the expression of key biofilm-related genes, algD and lasR, provides insights into the potential mechanisms of action. Rutin is a flavonoid present in several plants, particularly in amla and citrus fruits. Previous research indicates that Rutin has antibacterial properties towards Aeromonas hydrophila and enhances the efficacy of the flavonoid florfenicol28. Rutin is recognized for its ability to enhance wound healing due to its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory characteristics. It has shown encouraging outcomes in expediting wound healing and diminishing inflammation across various circumstances29. Additionally, Rutin improved the antibacterial activity of amikacin versus several bacterial strains30. Further research involving rats showed that Rutin enhances metabolic disorders in diabetic rats, facilitates wound healing, and mitigates inflammation and oxidative stress.

A significant drawback of Rutin is its low solubility in water31. Utilizing biocompatible polymers results in extended drug release, less toxicity, and improved antibacterial agent activity. The biocompatible polymers enhance medication efficacy and protect the medication from enzymatic breakdown, hence extending its action31. Chitosan (CS) has garnered significant interest as a nano-carrier owing to its non-toxic, biodegradable, and mucoadhesive characteristics32. Moreover, the antibacterial and anti-biofilm properties of chitosan (CS) and its nano-derivatives have been recorded against several pathogens, including Bacillus cereus and numerous other prevalent bacteria. Encapsulating pharmaceuticals into nanocarriers may markedly enhance their solubility, promote their transport, and allow for the controlled release of medicines33. Researchers have shown that encapsulating glycyrrhizic acid (GA) in chitosan may significantly diminish the release rate of GA34. Several studies have shown that chitosan and its derivatives have antimicrobial activity in controlled environments35,36. Recent research indicates that chitosan’s antibacterial mechanism may not be attributed to a single, unique target37. Researchers suggest a method in which chitosan interacts with teichoic acids in the cell walls of bacteria, possibly facilitating the extraction of membrane lipids. This series of occurrences eventually leads to the demise of bacterial cells37. Previous electron microscopy investigations have shown that chitosan inflicts considerable harm to the bacterial cell membrane. It attaches to the outer membrane, compromising its barrier function. The exact mechanism of chitosan’s action is not fully understood; nonetheless, its antibacterial qualities and varied physical attributes make it a significant material for several therapeutic uses38.

This work included encapsulating rut inside chitosan nanoparticles and evaluating its effects on clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa for the initial time. The properties of the produced nanoparticles exhibited efficient rut encapsulation inside the CS matrix. The zeta potential analysis of Rut-CS NPs was reported at 31.63 mV, indicating substantial colloidal durability of the nanoparticles. The agar well diffusion experiment was used to assess the suppression of bacterial proliferation. According to the results, Rut-CS NPs exhibited more potent inhibiting properties than free Rut individually. This indicates that encapsulation in CS nanoparticles improves Rut’s capacity to permeate the microbial barrier. This improvement results from the relationship between the positive charge present in CS and the negative-charged microbial cell membrane39. Furthermore, CS NPs promote the prolonged release of Rut, hence augmenting its antibacterial effectiveness.

Bacterial populations organized and encased in a matrix of self-produced polymers are called biofilms. Biofilms enable bacterial evasion of the host’s immune response and contribute to resistance to prevalent antibiotics40. The crystal violet labeling experiment demonstrated a significant decrease in biofilm development in bacterial strains after administration with Rut-CS NPs. In accordance with our results, previous studies have shown that Rut significantly reduces the production of biofilm by S. aureus10. The anti-biofilm efficacy of Rut-CS NPs is presumably attributable to the positive electrical charge of chitosan, facilitating its interaction with negative-charged elements in biofilms, including extracellular DNA (eDNA)10. This contact causes destruction of the cell membrane and leaking of cellular material, hence impeding the biofilm development process42. Moreover, Rut causes membrane disruption, resulting in the release of intracellular constituents and eventually hindering the development of bacterial biofilms43. The creation of biofilms safeguards microorganisms from host defenses and promotes the proliferation of infection44. Thus, the suppression of biofilm formation by Rut-CS NPs is essential in diminishing the pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa. The antimicrobial action of Rut-CS NPs versus P. aeruginosa includes a synergy between the inherent antibacterial qualities of chitosan (CS), the antimicrobial activity of rutin (Rut), and the transport and sustained release capabilities of the CS nanoparticles (NPs).

Prior research has shown that Rut-CS nanoparticles serve as an innovative treatment against Staphylococcus aureus infections by modifying cell shape and suppressing virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus10. This aligns with our research. The possibility of rutin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles (Rut-CS NPs) as antimicrobial agents was examined in both investigations. However, the previous study concentrated on S. aureus and examined the effects of the nanoparticles on cell morphology, DNA leakage, biofilm growth, and hemolytic action10. Our study examined the effectiveness of the nanoparticles towards multi-drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, specifically focusing on the suppression of bacterial growth and the inhibition of biofilm formation through targeting lasR and AlgD genes. Additionally, the study evaluated the toxicity of the nanoparticles on human dermal fibroblasts. In light of the escalating clinical challenge of multi-drug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains in hospital environments, exploring specific gene targets associated with biofilm formation yields a more mechanistic comprehension of antibacterial efficacy. At the same time, incorporating a cytotoxicity evaluation on human cells provides initial insights into the potential safety of nanoparticles for therapeutic use.

Previous research indicates that chitosan’s may be a strengthening ingredient in conjunction with antibiotics in pharmaceutical formulations45. This study is in line with our study in confirming the efficacy of chitosan methylation in combination with rutin. Both investigations examine the antibacterial efficacy of chitosan-derived compounds versus Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Previous studies investigated the in vitro drug-drug interactions of various chitosan forms (chitosan and chitosan oligosaccharide with differing deacetylation degrees) in conjunction with ten antibiotics towards both wild-type and mutant varieties of P. aeruginosa, revealing synergistic effects with sulfamethoxazole and indicating the involvement of the MexEF-OprN efflux pump in sulfamethoxazole resistance45. Our study explicitly examines the antibacterial activity of rutin encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles versus multi-drug-resistant P. aeruginosa, pressing the nanoparticle formulation’s capacity to limit bacterial growth and paramount resistance mechanisms.

The Rut-CS nanoparticle technology has significant promise as an inexpensive, cost-efficient, and non-toxic approach to infection control. The original work demonstrates in vitro antibacterial efficacy; however, more research is required to comprehensively confirm scalability and manufacturing costs to support the assertion of being “economical.” Nonetheless, rutin and chitosan are extensively acknowledged for their cost-effectiveness and accessibility, indicating a positive economic perspective for nanoparticle formation. Concerning safety, although the present work lacks in vivo toxicity or thorough biocompatibility evaluations, previous research—encompassing investigations of analogous chitosan-based nanoparticle systems—has shown little toxicity. Our prior research has shown that CS-casein-Amla nanoparticles displayed no toxicity to HDF cells at dosages ranging from 1.56 to 100 µg/mL (p < 0.01)46. These results endorse the ongoing investigation of Rut-CS nanoparticles as a secure and efficacious treatment strategy, especially against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa.

Conclusions

This research indicated that Rut-CS nanoparticles markedly decreased the expression of the algD and lasR genes in P. aeruginosa. Although algD is mostly responsible for alginate synthesis (a crucial element of the biofilm matrix) and lasR governs quorum sensing and the generation of virulence factors, their downregulation likely contributes to the noted antibacterial and antibiofilm actions. The interruption of lasR-regulated quorum sensing may influence the synthesis of surface molecules and efflux pumps essential for membrane integrity. Likewise, diminished algD expression and alginate production may modify the bacterial cell surface, enhancing its vulnerability to membrane-disrupting chemicals. The Rut-CS nanoparticles showed significant antibiofilm activity and efficacy against P. aeruginosa strains, indicating that nanoparticles provide a viable alternative to conventional antibiotics for treating bacterial infections. This economical, secure, and efficient nano-system can combat infections and provide antimicrobial therapies. Future studies should clarify the specific in vitro mechanisms of action and assess the persistence of Rut-CS nanoparticles. The antimicrobial efficiency of Rut-CS nanoparticles against P. aeruginosa is likely attributable to the synergistic interplay of chitosan’s intrinsic antibacterial characteristics, rutin’s antibacterial potency, and the improved transport and prolonged release facilitated by the chitosan nanoparticle system.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jean, S. S. et al. Epidemiology, treatment, and prevention of nosocomial bacterial pneumonia. J. Clin. Med. 9 (1), 275 (2020).

Horcajada, J. P. et al. Epidemiology and treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant P. aeruginosa infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32 (4), 10–128 (2019).

Pang, Z., Raudonis, R., Glick, B. R., Lin, T. J. & Cheng, Z. Antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 37 (1), 177–192 (2019).

Kunz Coyne, A. J., El Ghali, A., Holger, D., Rebold, N. & Rybak, M. J. Therapeutic strategies for emerging multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa. Infect. Dis. Therapy. 11 (2), 661–682 (2022).

Tarín-Pelló, A., Suay-García, B. & Pérez-Gracia, M. T. Antibiotic resistant bacteria: current situation and treatment options to accelerate the development of a new antimicrobial arsenal. Expert Rev. Anti-infective Therapy. 20 (8), 1095–1108 (2022).

Skendi, A., Irakli, M. & Chatzopoulou, P. Analysis of phenolic compounds in Greek plants of Lamiaceae family by HPLC. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromatic Plants. 6, 62–69 (2017).

Negahdari, R. et al. Therapeutic benefits of Rutin and its nanoformulations. Phytother. Res. 35 (4), 1719–1738 (2021).

Ahmad, B. et al. Phyllanthus emblica: A comprehensive review of its therapeutic benefits. South. Afr. J. Bot. 138, 278–310 (2021).

Behl, T. et al. Phytochemicals from plant foods as potential source of antiviral agents: an overview. Pharmaceuticals 14 (4), 381 (2021).

Esnaashari, F. & Zahmatkesh, H. Antivirulence activities of Rutin-loaded Chitosan nanoparticles against pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 24 (1), 328 (2024).

Almutairi, M. M. et al. Neuro-protective effect of Rutin against Cisplatin-induced neurotoxic rat model. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 17, 1–9 (2017).

Yi, L. et al. Synergistic effects and mechanisms of action of Rutin with conventional antibiotics against Escherichia coli. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (24), 13684 (2024).

Farha, A. K. et al. The anticancer potential of the dietary polyphenol rutin: current status, challenges, and perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62 (3), 832–859 (2022).

Vargas-Munévar, L. et al. Microencapsulation of Theobroma cacao L polyphenols: A high-value approach with in vitro anti-Trypanosoma cruzi, Immunomodulatory and antioxidant activities. Biomed. Pharmacother. 173, 116307 (2024).

Ebadi M, Kavousi M, Farahmand M. Investigation of the Apoptotic and Antimetastatic Effects of Nano‐Niosomes Containing the Plant Extract Anabasis setifera on HeLa: In Vitro Cervical Cancer Study. Chemistry & Biodiversity 22(4), e202402599 (2025).

Vittala Murthy, N. T., Paul, S. K., Chauhan, H. & Singh, S. Polymeric nanoparticles for transdermal delivery of polyphenols. Curr. Drug Deliv. 19 (2), 182–191 (2022).

Naveed, M. et al. Chitosan oligosaccharide (COS): an overview. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 129, 827–843 (2019).

Hamed, I., Özogul, F. & Regenstein, J. M. Industrial applications of crustacean by-products (chitin, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharides): A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 48, 40–50 (2016).

Tavares, T. D. et al. Activity of specialized biomolecules against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics 9 (6), 314 (2020).

Piri-Gharaghie, T. et al. Fabrication and characterization of thymol‐loaded Chitosan nanogels: improved antibacterial and anti‐biofilm activities with negligible cytotoxicity. Chem. Biodivers. 19 (3), e202100426 (2022).

Ramezani, H., Sazegar, H. & Rouhi, L. Chitosan-casein as novel drug delivery system for transferring Phyllanthus emblica to inhibit P. aeruginosa. BMC Biotechnol. 24 (1), 1–21 (2024).

de Abreu, P. M., Farias, P. G., Paiva, G. S., Almeida, A. M. & Morais, P. V. Persistence of microbial communities including P. aeruginosa in a hospital environment: a potential health hazard. BMC Microbiol. 14, 1–0 (2014).

AlSheikh, H. M. et al. Plant-based phytochemicals as possible alternative to antibiotics in combating bacterial drug resistance. Antibiotics 9 (8), 480 (2020).

Angelini, P. Plant-Derived antimicrobials and their crucial role in combating antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics 13 (8), 746 (2024).

Hussain, Y. et al. Antimicrobial potential of curcumin: therapeutic potential and challenges to clinical applications. Antibiotics 11 (3), 322 (2022).

Deepika, M. S. et al. Combined effect of a natural flavonoid Rutin from Citrus sinensis and conventional antibiotic gentamicin on P. aeruginosa biofilm formation. Food Control. 90, 282–294 (2018).

Amin, M. U., Khurram, M., Khattak, B. & Khan, J. Antibiotic additive and synergistic action of rutin, Morin and Quercetin against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 15, 1–2 (2015).

Deepika, M. S. et al. Antibacterial synergy between Rutin and florfenicol enhances therapeutic spectrum against drug resistant Aeromonas hydrophila. Microb. Pathog. 135, 103612 (2019).

Naseeb, M. et al. Rutin promotes wound healing by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation in Metformin-Controlled diabetes in rats. ACS Omega Mar 13. (2024).

Miklasińska-Majdanik, M. et al. The direction of the antibacterial effect of Rutin hydrate and Amikacin. Antibiotics 12 (9), 1469 (2023).

Semwal, R., Joshi, S. K., Semwal, R. B. & Semwal, D. K. Health benefits and limitations of rutin-A natural flavonoid with high nutraceutical value. Phytochem. Lett. 46, 119–128 (2021).

Iacob, A. T. et al. Recent biomedical approaches for Chitosan based materials as drug delivery nanocarriers. Pharmaceutics 13 (4), 587 (2021).

Liu, Y. & Feng, N. Nanocarriers for the delivery of active ingredients and fractions extracted from natural products used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 221, 60–76 (2015).

Naseriyeh, T. et al. Glycyrrhizic acid delivery system Chitosan-coated liposome as an adhesive anti-inflammation. Cell. Mol. Biol. 69 (4), 1–6 (2023).

Confederat, L. G., Tuchilus, C. G., Dragan, M., Sha’at, M. & Dragostin, O. M. Preparation and antimicrobial activity of Chitosan and its derivatives: A concise review. Molecules 26 (12), 3694 (2021).

Homaeii S, Kavousi M, Asgari EA. Investigating the apoptotic and antimetastatic effect of daphnetin-containing nano niosomes on MCF-7 cells. Advances in Cancer Biology-Metastasis 14:100139 (2025).

Raafat, D., Von Bargen, K., Haas, A. & Sahl, H. G. Insights into the mode of action of Chitosan as an antibacterial compound. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 (12), 3764–3773 (2008).

Mukherjee, M. & De, S. Investigation of antifouling and disinfection potential of Chitosan coated iron oxide-PAN Hollow fiber membrane using Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Mater. Sci. Engineering: C. 75, 133–148 (2017).

Zhang, S. et al. The adsorption behaviour of carbon nanodots modulated by cellular membrane potential. Environ. Science: Nano. 7 (3), 880–890 (2020).

Kavousi M, Chavoshi MS. Effect of coated carbon nanotubes with chitosan and cover of flaxseed in the induction of MDA-MB-231 apoptosis by analyzing the expression of Bax and Bcl-2. Meta Gene 26,100807 (2020).

Iaconis, A., De Plano, L. M., Caccamo, A., Franco, D. & Conoci, S. Anti-Biofilm strategies: A focused review on innovative approaches. Microorganisms 12 (4), 639 (2024).

Arciola, C. R., Campoccia, D., Speziale, P., Montanaro, L. & Costerton, J. W. Biofilm formation in Staphylococcus implant infections. A review of molecular mechanisms and implications for biofilm-resistant materials. Biomaterials 33 (26), 5967–5982 (2012).

Zou, Y. et al. Antibiotics-free nanoparticles eradicate Helicobacter pylori biofilms and intracellular bacteria. J. Controlled Release. 348, 370–385 (2022).

Kumar, A., Alam, A., Rani, M., Ehtesham, N. Z. & Hasnain, S. E. Biofilms: survival and defense strategy for pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 307 (8), 481–489 (2017).

Tin, S., Sakharkar, K. R., Lim, C. S. & Sakharkar, M. K. Activity of chitosans in combination with antibiotics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 5 (2), 153 (2009).

Ramezani, H., Sazegar, H. & Rouhi, L. Chitosan-casein as novel drug delivery system for transferring Phyllanthus emblica to inhibit Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Biotechnol. 24 (1), 101 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff members of the Biotechnology Research Center of the Islamic Azad University of Shahrekord Branch in Iran for their help and support. This research received no specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S., H.R.; methodology, H.S.; software, H.R. and L.R.; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University of Shahrekord Branch in Iran (IR.IAU.SHK.REC.1402).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramezani, H., Sazegar, H. & Rouhi, L. The antimicrobial efficacy of rutin encapsulated chitosan versus multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep 15, 22047 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06873-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06873-2