Abstract

Machine learning is a vital tool in advancing drug development by accurately predicting the physical, chemical, and biological properties of various compounds. This study utilizes MATLAB program-based algorithms to calculate topological indices and machine learning algorithms to explore their ability to predict the physio-chemical properties of asthma drugs. By combining machine learning with topological indices, we can conduct faster and more precise analyses of drug structures. As we deepen our understanding of the relationship between molecular structure and performance, the integration of machine learning with QSPR research highlights the significant potential of computational strategies in pharmaceutical discovery. The use of machine learning algorithms such as random forest and extreme gradient boosting is essential in this process. These algorithms leverage labeled data to predict complex molecular processes, aiding in the discovery of new medication options and enhancing their properties. These methods enhance the accuracy of physical and chemical property predictions, streamline the drug discovery process, and efficiently evaluate large datasets through machine learning. Ultimately, these advancements facilitate the development of innovative and effective treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition that impacts millions of individuals globally. Regarding the definition and classification of asthma, several views and opinions have been presented for many years1. The primary feature of asthma is the fluctuating difficulty in breathing. Several cell types and components, such as mast cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and epithelial cells, are involved in asthma, a chronic inflammatory disease of the respiratory system2. Coughing, wheezing, chest tightness, and dyspnea are some of the symptoms that are associated with this condition, which is characterized by inflammation and constriction of the airways3,4. A number of different things, including allergies, environmental irritants, physical exertion, and respiratory infections, can be the root cause of asthma, and the severity of the condition can vary from person to person. Understanding the fundamental mechanisms behind asthma is crucial for its management and treatment. In response to certain triggers, asthma sufferers frequently develop inflammation of the airways, which causes an excess of mucus production and constriction of the smooth muscles surrounding the airways. This results in the common symptoms that asthmatics experience. There are two types of asthma: allergic asthma is caused by allergens such as dust mites, pollen, or animal dander, while non-allergic asthma is triggered by factors such as cold air, smoke, exercise, or respiratory disorders. Finding their unique triggers is crucial for asthmatics in order to reduce exposure and stop their symptoms from getting worse. Asthma management entails a multi-modal strategy that combines pharmaceutical and non-pharmacological treatments. To reduce inflammation and widen the airways, bronchodilators, leukotriene modifiers, and inhaled corticosteroids are frequently utilized. Apart from taking medicine, people who have asthma are often recommended to stay away from triggers, have a healthy lifestyle, and get regular evaluations and monitoring from medical specialists.

Most of the time, the symptoms of asthma appear for the first time in early childhood. Although children of pre-school age frequently experience wheezing as a result of viral infections, only approximately half of these children go on to develop typical asthma when they are of school age. It is more likely that children who have wheezing that is frequent or persistent would have indications of airway inflammation and remodeling, reduced lung function, and symptoms that continue to be irritating well into adulthood5. Studies conducted inside communities at multiple times (between the 1960s and the early 1990s) revealed an increased prevalence of asthma; however, each study utilized their own technique, and very few of the studies were conducted in countries that were not high-income6. Asthma in children and young adults was the subject of repeated cross-sectional surveys from 1983 to 1996. There were a total of 178215 adults between the ages of 18 and 45 from 70 different countries who replied to questions regarding asthma and the symptoms that are associated with it7. A critical evaluation of these surveys revealed sixteen research that were of interest. The only studies that documented trends in present wheeze were those conducted in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.The remaining studies relied on diagnoses of asthma, which can be impacted by the condition’s prevalence and trends in diagnosis or labeling8,9.

In mathematical chemistry, degree-based topological indices are very useful tools that tell us a lot about the structure and physical features of chemical compounds. The molecular graph of a compound gives these numbers. In this graph, each atom is a node and each chemical link is an edge. This makes it possible to study molecule structure in a quantitative way. One very basic measure of topology is the degree of a vertex, which is the number of lines that connect it to other points. Using this idea as a base, degree-based topological indices figure out a number of attributes linked to various chemical properties and reactions by looking at the degrees of the nodes in a molecular graph. In many QSPR/QSAR investigations, topological indices are employed. It is established that there is a strong correlation between the topological indices and a number of the physicochemical characteristics of molecules. To create QSAR models, topological indicators with strong predictive power should be selected. We recommend that readers refer to10,11,12,13,14 for further information on the various applications of topological indices and also some graph related see15,16.

Now a days, QSPR has become a significant factor in drug development. In 2023, an examination of the QSPR study of asthma disease was carried out by D. Balasubramaniyan et al.17 using the methodology of neighborhood degree on TIs. In 2024, Micheal Arockiaraj et al.18 conducted a study on QSPR analysis, employing distance-based structural indices for drug compound in tuberculosis disease. They claimed that the selected properties highlight a robust correlation between the Wiener index and boiling point, enthalpy, and flash point, whereas the Padmakar-Ivan index displays a notable correlation with molar refraction, polarization, and molar volume. Abid Mehboob et al.19 are conducting research in 2024 on the QSPR analysis of hepatitis disease, utilizing eleven physical properties and 14 molecular descriptors through the degree method. They reveal that eight out of eleven properties, namely, boiling point, enthalpy, flash point, molar refractivity, LogP, molar volume, as well as molecular weight show a good correlation with all the 14 indices at the range of 0.7, 0.8 and 0.9. In 2024, Mehri Hasani and Masoud Ghods20 conducted research on the QSPR analysis of different beta-blocker medications for heart disease, focusing on the degree-based topological indices obtained from the M-polynomial. The relationship between indices and eight properties was determined using both linear and quadratic models. Harmonic index proved to be the most accurate predictor for boiling point, flash point, and enthalpy, whereas the modified third Zagreb index showed significant effectiveness in determining polarizability, molar refractivity, and molar volume through linear analysis. Moreover, the redefined third Zagreb index proved to be the most best fit predictor for polarizability and molar refractivity, while the second modified Zagreb index showing strong predictability for molar volume in quadratic analysis. The study by B. Kirana et al.21 in 2024 focused on the QSPR analysis and curvilinear regression applied to eleven TIs and four physical properties of Quinoline antibiotics. The outcomes indicates that the harmonic index showed a very good correlation with all considered indices for all the the three regression models.

Machine learning approaches have been shown to enhance the prediction of physicochemical and structural properties in drug discovery and material science applications22,23,24. XGBoost has also been successfully applied in QSPR/QSAR studies for its ability to handle non-linear relationships and feature interactions25,26, although performance may vary in small datasets.

Some basic definitions

A graph G is represented by the pair \(G\simeq (V, E)\) where V is a collection set of vertices and E is a collection set of edges. Whenever two vertices are adjacent in graph G, it is displayed as u \(\sim\) v. A line drawing between two vertex points signifies an edge represented as \(e = uv\). In G, the degree of a vertex v is calculated by counting its connected edges. Usually, it is denoted as \(d_{G}(v)\) or \(d_{v}\). According to chemical graph theory, a molecular structure can be interpreted as a mathematical graph consisting of atoms as vertices and bonds of atoms as edges. Typically, hydrogen atom are not considered in chemical graph. In this article all the chemical graphs is connected, finite, and simple.

Reducible first and second Zagreb index

The first and second Zag-indices are two graph invariants that were first introduced by Gutman and Trinajstic27. These are the oldest graph invariants that examined the total pi-electron energy and branching of carbon atom skeleton in molecular structure. These indices have extensive used in the field of chemical graph theory. In 2011, Kexiang Xu28 calculate these two indices by using the methodology of n-vertex graphs with clique number k. In 2022, S.R. Islam29 calculated the second Zagreb index for fuzzy graphs and conducted QSPR research using linear fitting model. In recent year 2023, Abid Mehboob et al.30 were inspired by the work of these indices and generate its new extension known as reducible first and second Zagreb indices. In this research they discussed the QSPR analysis, employing degree-based structural indices for drug compound in blood cancer disease. The mathematical formula of these indices are defined as;

The total number of vertices in graph G is represented by \(''n''\), while the degree of u and v denoted by \(d_{u}\) and \(d_{v}\), respectively.

Reducible reciprocal randic index

Reciprocal Randic index is named after Milan Randic, a croatian mathematician and chemist who introduced the concept in 197531. The reciprocal Randic index is a topological descriptors that quantifies the complexity of a chemical compound by taking into account the connectivity of its atoms. It is defined as the sum of the reciprocals of the square root of the degrees of all vertices in a molecular graph. In 2021, Z.Du et al.32 studied the relationship between Randic index and various topological descriptors like Zagreb indices, ABC-index, GA-index, and augmented Zagreb index. In 2022, C.T.Martinez-Martinez et al.33 compute the randic index by using vertex-degree method in Erdos-Renyi graphs and other random graphs. Suleyman Ediz et al.34 studied the QSPR analysis of total Zagreb indices and total Randic indices of octanes. The new extension of this index known as reducible reciprocal Randic index which is mathematically defined as;

Reducible first and second hyper Zagreb index

Shirdel et al.35 proposed a new molecular descriptor called the hyper Zagreb index, which is a distance-based version of the Zagreb index. The molecular complexity of a chemical compound is determined by the first hyper Zagreb index. This index has also been used in QSPR/QSAR studies, where it has shown a very good correlation with the biological activity molecules. M. Suresh and G. Sharmila Devi calculated the hyper Zagreb indices of graph based operation, which are related to lexicographic product36. Hao Zhou et al.37 observed the QSPR analysis of topological descriptors and biological properties for narcotic drugs. This index showed a high correlation with BP, VP, and EV at the range of 0.9. A new version of these indices has been introduced known as reducible first and hyper Zagreb index which is mathematically written as;

Reducible sigma index

Gutman proposed the concept of the Sigma index38, which was inspired by the Albertson index. In his article, he investigates the inverse problem of the sigma index and establishes that, for every given graph, this index will always have an even value. Reti39 examined the sigma index in comparison to a few well-known irregularity measures and pointed out a number of this index’s interesting features. The latest version of this index has been released under the name of reducible Sigma index, which is mathematically defined as;

Reducible forgotten index

Furtula and Gutman generates the new version of Zagreb indices called Forgotten index40. This index is also measure of branching and it has shown that it can predict outcomes similarly to \(M_{1}(G)\). However, for unknown reasons, it didn’t get much interest until 2015 when it was reinvented then this index received a significant attention. In the case of entropy and acentric factor, correlation coefficients higher than 0.95 are obtained for both \(M_{1}(G)\) and F(G)41. The recently developed extension of this index known as reducible forgotten index, which can be mathematically defined as;

Reducible \(1^{st}\) and \(2^{nd}\) Gourava Index

The Zagreb indices’ definition and its popularity served as inspiration for V. R. Kulli’s42 to introduce the two new indices known as first and second Gourava indices. He calculates this index for a few common types of graphs and applies the definition of this index for armchair and zigzag edge polyhex nanotubes. Furthermore, he computes the exact formulas for the friendship graph and wheel graph using these indices43. A new form of this index has been generated known as reducible first and second Gourava indices, which is mathematically defined as;

These degree-based reducible topological indices provide a straightforward yet effective method for describing the molecular structures. It is an invaluable instrument in the world of chemistry and beyond due to its broad applicability and capacity to predict a wide range of physical and chemical properties. The application of these reducible indices is probably going to keep expanding and advancing in numerous scientific fields. Their simplicity, which makes them simple to compute and understand, is their primary benefit.

Material and method

Our initial step involved establishing the edge partition and degree counting approach, which relies on graph connectivity to define molecular graphs. This method plays a crucial role in identifying structural characteristics. Then, topological indices (TIs) based on degree were determined by analyzing changes in node degrees within the molecular graph. For the purpose of simplification, we developed a custom MATLAB script to compute the proposed edge-based topological indices efficiently. Following this, Python code was utilized to construct machine learning models for analyzing physicochemical properties. Additionally, we utilized SPSS(Version 26.0, https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) software to investigate the relationships between the derived indices and experimental variables. To further validate our findings, we conducted a graphical analysis comparing actual and computed drug properties to ensure the accuracy and reliability of our results. To avoid the risk of overfitting and to ensure the generalizability of our models, we adopted a robust validation strategy. Specifically, the full dataset was partitioned into 80% training and 20% testing sets using train_test_split() from the scikit-learn library. An 80:20 train-test split was applied using scikit-learn’s train test split function with a fixed random state of 42. The list of compounds included in the training and testing sets is provided in Table 1, respectively. Additionally, a 10-fold cross-validation technique was employed on the training dataset to evaluate the performance of the models across multiple subsets. To ensure rigorous evaluation and prevent data leakage, all machine learning models were trained from scratch for each analysis step. Specifically, for the 80:20 train-test split, the models were trained exclusively on the training data, and the test data was used only for final performance evaluation. Additionally, for 10-fold cross-validation, a new model was trained for each fold using 90% of the data and validated on the remaining 10%. At no point was a model trained on the entire dataset used for testing or validation purposes. This technique divides the training data into 10 equal parts, iteratively training the model on 9 parts and validating on the remaining part. The average performance metrics obtained from the folds provided a stable and reliable assessment of the model’s predictive capability. The models performance was assessed using standard metrics including Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination (\(R^2\)).

Dataset acquisition strategy

-

We employed Python version 3.8 for determining topological indices and gathered the physicochemical properties from online databases such as ChemSpider (http://www.chemspider.com/Default.aspx) and

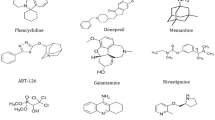

PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The treatment for asthma requires the use of various medications including Montelukast, Prednisone, Methylprednisolone, Dexamethasone, Terbutaline, etc., which are identified as a, b, c,..., m in Fig 1. During the analysis, topological descriptors were utilized as feature variables and physicochemical properties as target variables.

-

After labeling the dataset, we chose to employ supervised machine learning methods, including Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost (XGB), to analyze the data and obtain predictive insights. Random Forest was selected for its robustness and ability to manage overfitting through ensemble learning, whereas XGBoost applies gradient boosting to iteratively correct previous errors, offering high performance for complex data. Both models were trained using cross-validation to ensure the reliability of the results.

-

The main Python libraries used in model implementation included:

-

Jupyter notebook for an interactive environment,

-

pandas for data manipulation,

-

numpy for numerical computations,

-

scikit-learn for machine learning models including Random Forest and utility functions like train_test_split and cross_val_score,

-

xgboost for implementing the XGB algorithm,

-

matplotlib and seaborn for data visualization.

-

Model configuration and hyperparameters

All machine learning models were implemented in Python using the scikit-learn and xgboost libraries. The following hyperparameters were used for reproducibility:

-

Random Forest Regressor (RF):

-

Number of trees: n_estimators = 100

-

Maximum tree depth: max_depth = 10

-

Feature sampling: max_features = ’auto’

-

Minimum samples per leaf: min_samples_leaf = 1

-

-

XGBoost Regressor (XGB):

-

Number of trees: n_estimators = 100

-

Learning rate: learning_rate = 0.1

-

Maximum depth: max_depth = 6

-

Regularization parameters: reg_alpha = 0, reg_lambda = 1

-

Subsample ratio: subsample = 0.8

-

Mathematical formulation

Theorem 1

Let G be the graph of a montelukast drug, then the following axioms are hold:

-

\(\hbox {RM}_{1}\)(Montelukast)= 1681

-

\(\hbox {RM}_{2}\)(Montelukast) = 14708.75

-

RR(Montelukast) = 2297.12

-

\(\hbox {RHM}_{1}\)(Montelukast)= 65278.83

-

\(\hbox {RHM}_{2}\)(Montelukast)= 5300482.24

-

RS(Montelukast)= 6443.83

-

RF(Montelukast)=35861.33

-

\(\hbox {RG}_{1}\)(Montelukast)= 16389.74

-

\(\hbox {RG}_{2}\)(Montelukast)=581999.55

Proof

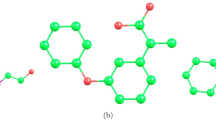

Figure 2 presents the visual representation of Montelukast drug, showing its two-dimensional chemical structure and molecular graph. The molecular graph of Montelukast comprises of 41 vertices and 45 edges. This structures has been analyzed using degree-based methodology. The vertex set of this particular structure, known as V(Montelukast), represents the collection of vertices \(v_{a}\) where ”a” ranges from 1 to 41. The collection of edges known as

E(Montelukast)=\(\{v_{1}v_{2}, v_{2}v_{3}, v_{3}v_{4},..., v_{40}v_{41}\}\). In this structure, we can identify the four vertex partitions: \(V_{1}\) includes vertices \(v\epsilon V(Montelukast)\) where d(v) = 1, \(V_{2}\) consisting of vertices \(v\epsilon V(Montelukast)\) where d(v) = 2, \(V_{3}\) comprises of vertices \(v\epsilon V(Montelukast)\) where d(v) = 3, and lastly, \(V_{4}\) includes vertices \(v\epsilon V(Montelukast)\) where d(v) = 4. Therefore, this structure contains seven edge bundles. The cardinalities of these bundles are: \(|E_{(1,3)}|=3\), \(|E_{(1,4)}|=3\), \(|E_{(2,2)}|=11\), \(|E_{(2,3)}|=20\), \(|E_{(2,4)}|=4\), \(|E_{(3,3)}|=3\), and \(|E_{(3,4)}|=1\). In order to determine all the nine defined reducible indices of Montelukast structure, the cardinalities of these edge bundles are employed for the calculation purposes which are calculated below.

-

RM1(Montelukast)

$$\begin{aligned}&= \sum \limits _{uv \varepsilon E(Montelukast)} \left( \frac{n}{d_{u}} + \frac{n}{d_{v}}\right) \\ & = 3\left( \frac{41}{1} + \frac{41}{3}\right) + 3\left( \frac{41}{1} + \frac{41}{4}\right) + 11\left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{2}\right) + 20\left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{3}\right) + 4\left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{4}\right) + 3\left( \frac{41}{3} + \frac{41}{3}\right) + 1\left( \frac{41}{3} + \frac{41}{4}\right) \\ & = 3(54.6667) + 3(51.25) + 11(41) + 20(34.1667) + 4(30.75) + 3(27.3333) + 1(23.9167)\\ & = 1681.00 \end{aligned}$$ -

RM2(Montelukast)

$$\begin{aligned} & = \sum \limits _{uv \varepsilon E(Montelukast)} \left( \frac{n}{d_{u}} \times \frac{n}{d_{v}}\right) \\ & = 3\left( \frac{41}{1} \times \frac{41}{3}\right) + 3\left( \frac{41}{1} \times \frac{41}{4}\right) + 11\left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{2}\right) + 20\left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{3}\right) + 4\left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{4}\right) + 3\left( \frac{41}{3} \times \frac{41}{3}\right) + 1\left( \frac{41}{3} \times \frac{41}{4}\right) \\ & = 3(560.3333) + 3(420.25) + 11(420.25) + 20(280.1667) + 4(210.125) + 3(186.7778) + 1(140.0833)\\ & = 14708.75 \end{aligned}$$ -

RR(Montelukast)

$$\begin{aligned} &= \sum \limits _{uv \varepsilon E(Montelukast)} \sqrt{\frac{n}{d_{u}} \times \frac{n}{d_{v}}}\\ & = 3\left( \sqrt{\frac{41}{1} \times \frac{41}{3}}\right) + 3\left( \sqrt{\frac{41}{1} \times \frac{41}{4}}\right) + 11\left( \sqrt{\frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{2}}\right) + 20\left( \sqrt{\frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{3}}\right) + 4\left( \sqrt{\frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{4}}\right) + 3\left( \sqrt{\frac{41}{3} \times \frac{41}{3}}\right) + 1\left( \sqrt{\frac{41}{3} \times \frac{41}{4}}\right) \\ & = 3(87.5093) + 3(65.6320) + 11(65.6230) + 20(43.7547) + 4(32.8160) + 3(29.1698) + 1(21.8773)\\ & = 2297.12 \end{aligned}$$ -

RHM1(Montelukast)

$$\begin{aligned} & = \sum \limits _{uv \varepsilon E(Montelukast)} \left( \frac{n}{d_{u}} + \frac{n}{d_{v}}\right) ^{2}\\ & = 3\left( \frac{41}{1} + \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + 3\left( \frac{41}{1} + \frac{41}{4}\right) ^{2} + 11\left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{2}\right) ^{2} + 20\left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + 4\left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{4}\right) ^{2} + 3\left( \frac{41}{3} + \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + 1\left( \frac{41}{3} + \frac{41}{4}\right) ^{2}\\ & = 3(2988.4444) + 3(2626.5625) + 11(1681) + 20(1167.3611) + 4(945.5625) + 3(747.1111) + 1(572.0069)\\ & = 65278.83 \end{aligned}$$ -

RHM2(Montelukast)

$$\begin{aligned} & = \sum \limits _{uv \varepsilon E(Montelukast)} \left( \frac{n}{d_{u}} \times \frac{n}{d_{v}}\right) ^{2}\\ & = 3\left( \frac{41}{1} \times \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + 3\left( \frac{41}{1} \times \frac{41}{4}\right) ^{2} + 11\left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{2}\right) ^{2} + 20\left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + 4\left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{4}\right) ^{2} + 3\left( \frac{41}{3} \times \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + 1\left( \frac{41}{3} \times \frac{41}{4}\right) ^{2}\\ & = 3(313973.4444) + 3(176610.0625) + 11(176610.0625) + 20(78493.3611) + 4(44152.5157) + 3(34885.9382) + 1(34885.9382)\\ & = 5300482.24 \end{aligned}$$ -

RS(Montelukast)

$$\begin{aligned} & = \sum \limits _{uv \varepsilon E(Montelukast)} \left( \frac{n}{d_{u}} - \frac{n}{d_{v}}\right) ^{2}\\ & = 3\left( \frac{41}{1} - \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + 3\left( \frac{41}{1} - \frac{41}{4}\right) ^{2} + 11\left( \frac{41}{2} - \frac{41}{2}\right) ^{2} + 20\left( \frac{41}{2} - \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + 4\left( \frac{41}{2} - \frac{41}{4}\right) ^{2} + 3\left( \frac{41}{3} - \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + 1\left( \frac{41}{3} - \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2}\\ & = 3(747.1111) + 3(945.5625) + 11(0) + 20(46.6944) + 4(105.0625) + 3(0) + 1(11.6737)\\ & = 6443.83 \end{aligned}$$ -

RF(Montelukast)

$$\begin{aligned} & = \sum \limits _{uv \varepsilon E(Montelukast)} \left( \left( \frac{n}{d_{u}} \right) ^{2} + \left( \frac{n}{d_{v}} \right) ^{2} \right) \\ & = 3\left( \left( \frac{41}{1}\right) ^{2} + \left( \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2}\right) + 3\left( \left( \frac{41}{1}\right) ^{2} + \left( \frac{41}{4}\right) ^{2}\right) + 11\left( \left( \frac{41}{2}\right) ^{2} + \left( \frac{41}{2}\right) ^{2}\right) + 20\left( \left( \frac{41}{2}\right) ^{2} + \left( \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2}\right) + 4\left( \left( \frac{41}{2}\right) ^{2} + \left( \frac{41}{4}\right) ^{2}\right) \\ & \hspace{10mm} + 3\left( \left( \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + \left( \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2}\right) + 1\left( \left( \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2} + \left( \frac{41}{3}\right) ^{2}\right) \\ & = 3(1867.7778) + 3(1786.0625) + 11(840.5) + 20(607.0278) + 4(525.3125) + 3(373.5556) + 1(291.8402)\\ & = 35861.33 \end{aligned}$$ -

RG1(Montelukast)

$$\begin{aligned} & = \sum \limits _{uv \varepsilon E(Montelukast)} \left( \frac{n}{d_{u}} + \frac{n}{d_{v}} + \left( \frac{n}{d_{u}} \times \frac{n}{d_{v}}\right) \right) \\ & = 3\left( \frac{41}{1} + \frac{41}{3} + \left( \frac{41}{1} \times \frac{41}{3}\right) \right) + 3\left( \frac{41}{1} + \frac{41}{4} + \left( \frac{41}{1} \times \frac{41}{4}\right) \right) + 11\left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{2} + \left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{2}\right) \right) \\ & \hspace{10mm} + 20\left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{3} + \left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{3}\right) \right) + 4\left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{4} + \left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{4}\right) \right) + 3\left( \frac{41}{3} + \frac{41}{3} + \left( \frac{41}{3} \times \frac{41}{3}\right) \right) \\ & \hspace{10mm} + 1\left( \frac{41}{3} + \frac{41}{4} + \left( \frac{41}{3} \times \frac{41}{4}\right) \right) \\ & = 3(615) + 3(471.5) + 11(461.25) + 20(314.3333) + 4(240.875) + 3(214.1111) + 1(164)\\ & = 16389.74 \end{aligned}$$ -

RG2(Montelukast)

$$\begin{aligned} & = \sum \limits _{uv \varepsilon E(Montelukast)} \left( \left( \frac{n}{d_{u}} + \frac{n}{d_{v}} \right) \left( \frac{n}{d_{u}} \times \frac{n}{d_{v}} \right) \right) \\ & = 3\left( \left( \frac{41}{1} + \frac{41}{3} \right) \left( \frac{41}{1} \times \frac{41}{3} \right) \right) + 3\left( \left( \frac{41}{1} + \frac{41}{4} \right) \left( \frac{41}{1} \times \frac{41}{4} \right) \right) + 11\left( \left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{2} \right) \left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{2} \right) \right) \\ & \hspace{10mm} + 20\left( \left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{3} \right) \left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{3} \right) \right) + 4\left( \left( \frac{41}{2} + \frac{41}{4} \right) \left( \frac{41}{2} \times \frac{41}{4} \right) \right) + 3\left( \left( \frac{41}{3} + \frac{41}{3} \right) \left( \frac{41}{3} \times \frac{41}{3} \right) \right) \\ & \hspace{10mm} + 1\left( \left( \frac{41}{3} + \frac{41}{4} \right) \left( \frac{41}{3} \times \frac{41}{4} \right) \right) \\ & = 3(30631.5556) + 3(21537.8125) + 11(17230.25) + 20(9572.3611) + 4(6461.3438) + 3(5105.2592) + 1(3350.3263)\\ & = 581999.55 \end{aligned}$$

Algorithm 1: Computation of reducible topological indices

The following pseudocode outlines the general procedure to compute various reducible topological indices from a molecular graph represented as an adjacency matrix.

Remark

The reducible topological indices of alternate medicines can be determined using a similar method as illustrated in Theorem 1 and their calculated results displayed in Table 2.

Our input in this process includes crafting a efficient MATLAB program (Algorithm 1) for determining these indices. In particular, our strategy is effective in rapidly computing by incorporating adjacency metrics for all molecular graphs in a streamlined way. This innovative method boosts the field by offering a simple procedures, enhanced accuracy, and time-saving benefits for computing topological indices. Both Theorem 1 and Algorithm 1 are applicable for calculating topological indices, yet the algorithmic method proves to be more efficient and advantageous. Moreover, Table 3 present the data of eight physical properties for asthma drugs, which are collected form online resources.

Linear regression model

Linear regression plays an integral role in supervised machine learning by predicting the relationship between a dependent variable and several independent variables. It is an effective technique for comprehending and forecasting how the values of the independent variables will affect the behavior of the dependent variable. Nowadays, multiple variations of regression analysis have gained attention; however, this manuscript specifically focuses on the most common type: simple linear analysis. Simple linear regression relies on a singular independent variable to predict the behavior exhibited by a dependent variable. It is assumed that the variables have a linear relationship, and the objective is to find a straight line that best fits the data points by minimizing the sum of squared differences between the predicted and observed values. The regression equation serves as a valuable tool for consistently delivering QSPR results through its formulaic expression P = U + V (TI). Here, P stands for physical characteristics of asthma drugs, while U remains constant. The variable V represent the regression coefficients and TI stands for defined topological indices. This model have been used to investigate the significant level of the relationship between each reducible indices and the chemical characteristics of the asthma medications. Below are the physio-chemical properties and linear regression equations derived with respect to TIs.

-

1.

Regression models for reducible first Zagreb index

$$\begin{aligned}&BP=395.4965 + 0.1824[RM_{1}(G)]\\&VP=0.9969 + 0.0016[RM_{1}(G)]\\&EV=66.8747 + 0.0281[RM_{1}(G)]\\&FP=195.2876 + 0.0879[RM_{1}(G)]\\&MR=45.2474 + 0.0626[RM_{1}(G)]\\&C=141.0306 + 0.5019[RM_{1}(G)]\\&LogP=-0.1553 + 0.0034[RM_{1}(G)]\\&Pol=17.9552 + 0.0248[RM_{1}(G)]\\&MV=139.8529 + 0.1742[RM_{1}(G)]\\&MW=190.9336 + 0.2104[RM_{1}(G)] \end{aligned}$$ -

2.

Regression models for reducible second Zagreb index

$$\begin{aligned}&BP=432.7991 + 0.0195[RM_{2}(G)]\\&VP=1.3860 + 0.0002[RM_{2}(G)]\\&EV=72.9719 + 0.0030[RM_{2}(G)]\\&FP=217.1759 + 0.0088[RM_{2}(G)]\\&MR=57.5222 + 0.0068[RM_{2}(G)]\\&C=253.8227 + 0.0521[RM_{2}(G)]\\&LogP=0.4001 + 0.0004[RM_{2}(G)]\\&Pol=22.8171 + 0.0027[RM_{2}(G)]\\&MV=174.3069 + 0.0189[RM_{2}(G)]\\&MW=233.3744 + 0.0226[RM_{2}(G)] \end{aligned}$$ -

3.

Regression models for reducible reciprocal Randic index

$$\begin{aligned}&BP=470.5989 + 0.1550[RR(G)]\\&VP=1.9107 + 0.0008[RR(G)]\\&EV=79.7388 + 0.0214[RR(G)]\\&FP=223.7574 + 0.0899[RR(G)]\\&MR= 69.7704 + 0.0557[RR(G)]\\&C=391.1892 + 0.3412[RR(G)]\\&LogP= 0.9669 + 0.0034[RR(G)]\\&Pol=27.6660 + 0.0221[RR(G)]\\&MV=214.8496 + 0.1417[RR(G)]\\&MW=280.1007 + 0.1739[RR(G)] \end{aligned}$$ -

4.

Regression models for reducible first hyper Zagreb index

$$\begin{aligned}&BP=435.1646 + 0.0040[RHM_{1}(G)]\\&VP=1.2886 + 0.0000[RHM_{1}(G)]\\&EV=72.9503 + 0.0006[RHM_{1}(G)]\\&FP=218.7744 + 0.0018[RHM_{1}(G)]\\&MR=58.8336 + 0.0014[RHM_{1}(G)]\\&C=246.3700 + 0.0112[RHM_{1}(G)]\\&LogP=0.5157 + 0.0001[RHM_{1}(G)]\\&Pol=0.5157 + 0.0001[RHM_{1}(G)]\\&MV=177.6460 + 0.0038[RHM_{1}(G)]\\&MW=177.6460 + 0.0038[RHM_{1}(G)] \end{aligned}$$ -

5.

Regression models for reducible second hyper Zagreb index

$$\begin{aligned}&BP=471.0217 + 0.0000[RHM_{2}(G)]\\&VP=1.6231 + 0.0000[RHM_{2}(G)]\\&EV=78.6730 + 0.0000[RHM_{2}(G)]\\&FP=240.0476 + 0.0000[RHM_{2}(G)]\\&MR= 70.4976 + 0.0000[RHM_{2}(G)]\\&C=347.7691 + 0.0001[RHM_{2}(G)]\\&LogP= 1.0593 + 0.0000[RHM_{2}(G)]\\&Pol= 27.9587 + 0.0000[RHM_{2}(G)]\\&MV=210.4010 + 0.0000[RHM_{2}(G)]\\&MW=276.4249 + 0.0001[RHM_{2}(G)] \end{aligned}$$ -

6.

Regression models for reducible Sigma index

$$\begin{aligned}&BP=458.0754 + 0.0221[RS(G)]\\&VP=1.0179 + 0.0003[RS(G)]\\&EV=74.9887 + 0.0038[RS(G)]\\&FP=235.7049 + 0.0082[RS(G)]\\&MR=67.8365 + 0.0073[RS(G)]\\&C=248.3887 + 0.0765[RS(G)]\\&LogP=1.0931 + 0.0004[RS(G)]\\&Pol=26.9090 + 0.0029[RS(G)]\\&MV=200.4635 + 0.0209[RS(G)]\\&MW=263.9381 + 0.0253[RS(G)] \end{aligned}$$ -

7.

Regression models for reducible Forgotten index

$$\begin{aligned}&BP=436.5468 + 0.0069[RF(G)]\\&VP=1.2369 + 0.0001[RF(G)]\\&EV=72.9621 + 0.0011[RF(G)]\\&FP=220.3297 + 0.0030[RF(G)]\\&MR= 59.4595 + 0.0024[RF(G)]\\&C= 241.8753 + 0.0198[RF(G)]\\&LogP= 0.5607 + 0.0001[RF(G)]\\&Pol= 23.5867 + 0.0009[RF(G)]\\&MV=179.0820 + 0.0066[RF(G)]\\&MW=238.4337 + 0.0080[RF(G)] \end{aligned}$$ -

8.

Regression models for reducible first Gourava index

$$\begin{aligned}&BP=430.4493 + 0.0172[RG_{1}(G)]\\&VP=1.3301 + 0.0001[RG_{1}(G))]\\&EV=72.4750 + 0.0026[RG_{1}(G)]\\&FP=215.0942 + 0.0078[RG_{1}(G)]\\&MR=57.0314 + 0.0059[RG_{1}(G)]\\&C=243.8847 + 0.0463[RG_{1}(G)]\\&LogP=0.4086 + 0.0003[RG_{1}(G)]\\&Pol= 22.6237 + 0.0023[RG_{1}(G)]\\&MV=173.0053 + 0.0164[RG_{1}(G)]\\&MW=231.1765 + 0.0198[RG_{1}(G)] \end{aligned}$$ -

9.

Regression models for reducible second Gourava index

$$\begin{aligned}&BP=457.1951 + 0.0004[RG_{2}(G)]\\&VP=1.4908 + 0.0000[RG_{2}(G))]\\&EV=76.4518 + 0.0001[RG_{2}(G)]\\&FP=231.4103 + 0.0002[RG_{2}(G)]\\&MR=66.1366 + 0.0001[RG_{2}(G)]\\&C=308.9992 + 0.0011[RG_{2}(G)]\\&LogP=308.9992 + 0.0011[RG_{2}(G)]\\&Pol= 26.2316 + 0.0001[RG_{2}(G)]\\&MV=198.2069 + 0.0004[RG_{2}(G)]\\&MW=261.4565 + 0.0005[RG_{2}(G)] \end{aligned}$$

Computation of statistical parameters

Statistical parameters is necessary for assessing the performance and reliability of the developed models in the context of QSPR analysis. The computed correlation coefficients between every topological indicator and the ten physio-chemical parameters are presented in Table 4. The comparison between the correlation coefficients of all reducible topological indices is exhibited using 2D bar graphs, as shown in Fig. 3. The comparison of Topological Indices (TIs) with correlation coefficients through statistical parameters is advantageous for model analysis. The mean variability between predicted and actual values is captured by the standard error (SE) in regression models, with Tables 5, 6, and 7 presenting data on SE-value, F-stats, and significance levels p-values. An important result is observed when the F-value exceeds 2.5. The significance of the F-statistic can be understood by analyzing its associated p-value. A small p-value, typically below or equal to 0.05, demonstrate a robust and significant connection. Alternatively, if the p-value surpasses 0.05, it suggests that there is no significant link present. Most of our correlation results satisfy these criteria as the correlations (r) values are greater than or equal to 0.7, with p-values less than or equal to 0.05 and F-values exceeding 2.5, indicating a strong and positive correlation between physical properties and reducible indices for asthma drugs.

Supervised machine learning

The technique of supervised machine learning trains algorithms to predict outcomes by analyzing labeled data sets for patterns. In the relam of artificial intelligence encompasses machine learning which specializes in developing statistical models and algorithms that enable computers to learn and decide without explicit programming. Machine learning strategies like Random Forest Algorithm (RFA), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), and linear analysis are commonly used in drug development processes. RFA and XGB are the two models were used as the predictive models. In simpler models such as linear analysis tools like linear regression proves to be useful, however more advanced ensemble techniques such as XGB and RFA excel in managing the complexity of nonlinear relationships and interactions within datasets. These models are utilized to predict attributes commonly analyzed in lab settings, ultimately saving both time and resources typically expended during evaluations. These modern techniques are more effective than traditional computation methods when it comes to processing and examining complex but limited data sets in order to deduce chemical interactions quickly.

Algorithm 2

Steps for RFA and XGB for QSPR model of asthma

\({\textbf {Step 1:}}\)

-

i

To begin analyzing the dataset, it is crucial to import key libraries such as NumPy, Pandas, Seaborn, Scikit-learn, RandomForestRegressor, XGBRegressor, Matplotlib, and Plot\(\_\)tree into Python.

-

ii

You can define the dataset in Python using a dictionary with key-value pairs to show the relationships between data points and properties across features. This clarifies data analysis and visualization.

\({\textbf {Step 2:}}\)

-

iii

After creating the data-set dictionary, prepare the data for analysis.

-

iv

The transformation of the dictionary into a pandas DataFrame can be done using the pd.DataFrame(data) function. This will enable more efficient data management and analysis.

-

v

It is crucial to distinguish between the attributes (X) and the outcome variable (y).

-

vi

when working with the data. This will help in understanding the relationships between different variables and in making accurate predictions or conclusions based on the data.

\({\textbf {Step 3:}}\)

-

vii

Train a RandomForestRegressor and XGBoost regression model.

-

viii

Assess the model’s performance and predictive abilities on novel data to determine its efficacy.

\({\textbf {Step 4:}}\)

ix- Create a scatter plot to compare predicted and actual values, positioning actual values on the y-axis and expected values on the x-axis.

x- Furthermore, display the predicted values in a tabular format similar to a DataFrame or structured array to facilitate comparison with observed values.

Random forest

The trademarked method Random Forest, which combines several decision tree results to generate one final conclusion, was invented by Leo Breiman and Adele Cutler. Before starting the training process, the three main hyperparameters of random forest algorithms should be clearly defined. When making decisions, one should consider node dimensions, tree count, and sampled feature count. RFA chooses many random segments from the training set using a bootstrapping approach. By means of each subset, the decision tree experiences training under a procedure known as a bootstraps sample. Every bootstrap sample at every split point generates a fresh decision tree using a randomized feature selection. Because of this randomization, which helps to lower tree correlation, the model performs better generally. Every tree is let to grow naturally without any pruning, so attaining their full depth. Following the Random Forest technique, the forecasts of every single tree are aggregated after they are produced. Though they can be slow because they must process data for every individual decision tree, random forest algorithms’ capacity to manage big datasets helps them to generate reliable forecasts. The outcome for the targeted variable \({\bar{y}}\) in a random forest regression models is calculated by using the following mathematical formula:

With n the number of trees in the forest, \({\bar{y}}\) denotes the expected output whereas \(f_{i}(x)\) denotes the expected output from individual decision trees. Figures 4 and 5 respectively contain the BP and VP decision trees. As shown in Fig. 6, using violin plots facilitates simple identification of data distribution gaps, therefore enabling a visual evaluation of prediction accuracy against actual values. Using four main error criteria such as Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and \(R^{2}\) for the model’s performance was assessed following this visual analysis. Table 9 shows the formulas applied to determine these error levels together with the corresponding output error measurements data. By means of data from both the violin plots and the tables, the accuracy and performance of the random forest algorithm were extensively examined, therefore offering a whole assessment of the predictive powers of the model.

-

MSE = \(\frac{1}{n} \sum (\text {actual} - \text {predicted})^{2}\)

-

MAE = \(\frac{1}{n} \sum |\text {actual} - \text {predicted}|\)

-

RMSE = \(\frac{1}{n} \sqrt{\sum (\text {actual} - \text {predicted})^{2}}\)

Extreme gradient boosting

The Extreme Gradient Boosting algorithm, also known as XGBoost, is a distributed library used for training gradient-boosted decision trees in machine learning applications. It provides parallel tree boosting. The utilization of yes/no missing feature questions allows decision trees to create a model that predicts outcomes while calculating the minimum number of questions needed to ensure accuracy. XGB has a highly effective machine learning approach recognized for its predictive accuracy within mathematical modeling. By examining a dataset of molecular descriptors, we focused on evaluating the predictive power of XGB for various chemical properties. The model was initially trained with 100 estimators, resulting in exceptional performance marked by low error metrics such as MAE, MSE, and RMSE, and almost ideal \(R^{2}\) value as shown in Table 11. Despite using 100 estimators for both BP and VP, only 5 decision trees were visualized for interpretability, as depicted in Figs. 7 and 8. The effectiveness of the model and any variations can be assessed by examining the violon plot of the actual and predicted values shown in Fig. 9. Doubts arose about the reliability of decision tree visualizations and violin plots in accurately depicting how trained models behave, especially when comparing actual values to their predicted values.

Comparative analysis of actual and predicted properties

The Random Forest Algorithm (RFA) and XGBoost (XGB) model were employed to analyze various properties of asthma drugs to assess their predictive performance and visualization capabilities on a specific dataset. To evaluate the accuracy of the models for different properties, error metrics such as MAE, MSE, RMSE, and \(R^{2}\) score were calculated. The MAE values for the properties in RFA ranged from 0.289 to 43.942, while in XGB they varied from 0.00002 to 0.00008, indicating that XGB had a significantly lower average prediction error. Similarly, XGB had lower MSE values compared to RFA. The RMSE values in XGB ranged from 0.0004 to 0.0010, whereas in RFA the range was from 0.375 to 57.806, highlighting that XGB is the superior accuracy in predictions. The \(R^{2}\) score for properties using XGB consistently reached 0.999, in contrast to the range of 0.799 to 0.964 observed in RFA models, this shows that XGB is the exceptional ability to explain almost all data variance. Both XGB and RFA models performed well in predicting the characteristics of asthma drugs, but XGB showing slightly better results. So, this implies that the XGB algorithm typically generates more accurate predictions regarding the physio-chemical properties of asthma drugs. Tables 8, 10 and 12 display the predicting values of RFA and XGB in relation to physical properties alongside the graphical comparison of actual and computed values for all properties between RFA and XGB are presented in Figs 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 along with the comparison of the all four error matrices between RFA and XGB are depicted in Fig. 15.

Evaluation with cross-validation and test set

To ensure that the reported performance is not biased by overfitting, we evaluated all models using both a held-out test set and 10-fold cross-validation. The test set metrics reflect model generalization on unseen data, while cross-validation provides performance stability across different data partitions. This approach is particularly important given the limited size of the dataset are shown in Table 13.

Comparison with baseline model

To provide a benchmark for model performance, we implemented multivariate linear regression (MLR) using the same feature set of topological indices. The evaluation metrics for MLR were compared against those of Random Forest and XGBoost models. As expected, the non-linear models outperformed the linear regression baseline, particularly for non-additive molecular properties. This comparison supports the relevance of using advanced ensemble methods in QSPR modeling are shown in Table 14.

Comparison with additional benchmark models

To enhance model diversity and align with standard practices in QSPR modeling, we extended our analysis by including two additional algorithms: Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Decision Tree Regression (DTR). These models are widely used in cheminformatics for their capability to capture complex relationships in small- to medium-sized datasets.

Both SVR and DTR were trained using the same feature set of topological indices and validated using the 80:20 train-test split and 10-fold cross-validation, consistent with our methodology for the other models. As shown in Table 15, the SVR model performed better than linear regression and decision trees, achieving a test set \(R^2\) of 0.857. However, it was still outperformed by ensemble models like Random Forest (\(R^2 = 0.922\)) and XGBoost (\(R^2 = 0.941\)), which exhibited stronger generalization capabilities. The decision tree regressor, while interpretable, had relatively lower performance compared to ensemble-based approaches. These comparisons reinforce the advantage of using ensemble learning models for QSPR tasks, particularly when dealing with a limited dataset and non-linear feature-property relationships.

Conclusion

Our analysis results offer valuable insights into the effectiveness of the drugs being studied for treating asthma. In our study, we evaluated the predictive capabilities of RFA, Linear Regression, and XGB in determining physiochemical properties. Various statistical metrics such as MAE, MSE, and RMSE were used to evaluate the effectiveness of predictive algorithms like RFA and XGB. The efficiency of different models was compared by analyzing error indicators through visual representations such as tables and graphs. Additionally, decision trees were created using the model, and the results were presented to understand the model’s structure. A violin plot was generated to compare the actual and predicted values of RFA and XGB, demonstrating the robust performance of the model. XGB showed superior predictive accuracy compared to RFA, with lower MAE, MSE, and RMSE values. Furthermore, XGB exhibited greater accuracy in fitting the data, as evidenced by its higher \(R^{2}\) values in comparison to RFA. This highlights why XGB is effective for predictive modeling tasks when compared to the complexities of graphs and error tables, as it is derived from iterative prediction refinement. Future research could explore additional methods and techniques for optimizing data sets, leading to advancements in larger-scale predictive modeling projects within the pharmaceutical industry. The development of new machine learning techniques will expand predictive modeling possibilities. This study emphasizes the effectiveness of utilizing advanced algorithms to enhance drug development processes.

Future work

While this study successfully demonstrates the potential of QSPR modeling using topological indices for predicting physicochemical properties of asthma-related drugs, we recognize the limitations posed by the relatively small dataset. In future work, we aim to expand the dataset by incorporating a broader range of asthma-related compounds, including investigational drugs currently in clinical or preclinical development. This will improve the generalizability and predictive power of the proposed models. Additionally, integrating advanced descriptors and exploring ensemble-based deep learning techniques may further enhance model accuracy. Extending the analysis to include biological activity prediction through QSAR modeling is also a potential direction for creating a more comprehensive drug evaluation framework.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ong, K. Y. Whats new in the Global Initiative for Asthma 2018 report and beyond. Allergo J. Int. 28, 63–72 (2019).

Mims, J. W. (2015). Asthma: definitions and pathophysiology. In International forum of allergy & rhinology (Vol. 5, No. S1, pp. S2-S6).

Patadia, M. O., Murrill, L. L. & Corey, J. Asthma: symptoms and presentation. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 47(1), 23–32 (2014).

Krishnan, J. A. et al. Asthma outcomes: symptoms. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129(3), S124–S135 (2012).

Tai, A. et al. Outcomes of childhood asthma to the age of 50 years. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 133(6), 1572–1578 (2014).

Douwes, J., Boezea, M., & Pearce, N. (2009). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Oxford textbook of public health, Volume 3: the practice of public health, (Ed. 5), 1021-1045.

To, T. et al. Global asthma prevalence in adults: Findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health 12(1), 1–8 (2012).

Anderson, H. R. Is the prevalence of asthma changing. Arch. Dis. Child. 64(1), 172 (1989).

Magnus, P. & Jaakkola, J. J. Secular trend in the occurrence of asthma among children and young adults: Critical appraisal of repeated cross sectional surveys. BMJ 314(7097), 1795 (1997).

Mekenyan, O., Bonchev, D., Sabljic, A. & Trinajstic, N. Applications of topological indices to QSAR The use of the Balaban index and the electropy index for correlations with toxicity of ethers on mice. Acta Pharmaceutica Jugoslavica 37(1), 75–86 (1987).

Estrada, E. & Uriarte, E. Recent advances on the role of topological indices in drug discovery research. Curr. Med. Chem. 8(13), 1573–1588 (2001).

Basak, S. C., Mills, D., Gute, B. D., Grunwald, G. D., & Balaban, A. T. (2002). Applications of topological indices in the property/bioactivity/toxicity prediction of chemicals. In Topology in Chemistry (pp. 113-184). Woodhead Publishing.

Pyka, A. Application of topological indices for prediction of the biological activity of selected alkoxyphenols. Acta Pol. Pharm. 59(5), 347–352 (2002).

Natarajan, R., Kamalakanan, P., & Nirdosh, I. (2003). Applications of topological indices to structure-activity relationship modelling and selection of mineral collectors.

Mahboob, A., Rasheed, M. W., Bayati, J. H. H., & Hanif, I. (2023). Computation of several Banhatti and Reven invariants of silicon carbides. Baghdad Science Journal, 20(3 (Suppl.)), 1099-1099.

Hussein Bayati, J. H., Mahboob, A., & Rasheed, M. W. (2024). On Partition Dimension and Domination of Abid-Waheed \((AW)_{r}^{s}\) Graph. Baghdad Science Journal, 21(5).

Balasubramaniyan, D. & Chidambaram, N. On some neighbourhood degree-based topological indices with QSPR analysis of asthma drugs. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138(9), 823 (2023).

Arockiaraj, M., Campena, F. J. H., Greeni, A. B., Ghani, M. U., Gajavalli, S., Tchier, F., & Jan, A. Z. (2024). QSPR analysis of distance-based structural indices for drug compounds in tuberculosis treatment. Heliyon, 10(2).

Mahboob, A., Rasheed, M. W., Dhiaa, A. M., Hanif, I., & Amin, L. (2024). On Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Anti-Hepatitis Prescription Drugs Using a Linear Regression Model. Heliyon.

Hasani, M. & Ghods, M. Topological indices and QSPR analysis of some chemical structures applied for the treatment of heart patients. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 124(1), e27234 (2024).

Kirana, B., Shanmukha, M. C., & Usha, A. (2024). A QSPR analysis and curvilinear regression for various degree-based topological indices of Quinolone antibiotics.

Huang, S., Xu, P. & Liu, Y. Machine learning applications for mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Anal. Chim. Acta 914, 1–13 (2016).

Cheng, F., Li, W., Liu, G. & Tang, Y. Machine learning and cheminformatics approaches for drug discovery. Chem. Rev. 112(1), 379–434 (2012).

Lavecchia, A. Machine-learning approaches in drug discovery: Methods and applications. Drug Discov. Today 20(3), 318–331 (2015).

T. Chen and C. Guestrin, XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system, Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pp. 785-794, 2016.

Lo, Y.-C., Rensi, S. E., Torng, W. & Altman, R. B. Comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms for QSPR modeling of aqueous solubility. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60(4), 1714–1723 (2020).

Gutman, I., & Trinajstic, N. (1972). Graph theory and molecular orbitals. Total f-electron energy of alternant hydrocarbons. Chemical physics letters, 17(4), 535-538.

Xu, K. The Zagreb indices of graphs with a given clique number. Appl. Math. Lett. 24(6), 1026–1030 (2011).

Islam, S. R. & Pal, M. Second Zagreb index for fuzzy graphs and its application in mathematical chemistry. Iranian J. Fuzzy Syst. 20(1), 119–136 (2023).

Mahboob, A., Rasheed, M. W., Amin, L. & Hanif, I. A study of novel molecular descriptors and quantitative structure-property relationship analysis of blood cancer drugs. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138(9), 856 (2023).

Randic, M. Characterization of molecular branching. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97(23), 6609–6615 (1975).

Du, Z., Jahanbai, A. & Sheikholeslami, S. M. Relationships between Randic index and other topological indices. Commun. Combinatorics Optim. 6(1), 137–154 (2021).

Martinez-Martinez, C. T., Mendez-Bermudez, J. A., Rodriguez, J. M. & Sigarreta, J. M. Computational and analytical studies of the Randic index in Erdos-Renyi models. Appl. Math. Comput. 377, 125137 (2020).

Ediza, S. et al. A note on QSPR analysis of total Zagreb and total Randic Indices of octanes. Eurasian Chemial Commun. 3, 139–45 (2021).

Shirdel, G. H., Rezapour, H., & Sayadi, A. M. (2013). The hyper-Zagreb index of graph operations.

Suresh, M., & Devi, G. S. (2020, November). Some operations in hyper Zagreb indices. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2277, No. 1, p. 140003). AIP Publishing LLC.

Zhou, H., Mahboob, A., Rasheed, M. W., Ovais, A., Siddiqui, M. K., & Cheema, I. Z. (2023). On QSPR Analysis of Molecular Descriptor and Thermodynamic Features of Narcotic Drugs. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds, 1-21.

Shanmukha, M. C., Basavarajappa, N. S., Shilpa, K. C., & Usha, A. (2020). Degree-based topological indices on anticancer drugs with QSPR analysis. Heliyon, 6(6).

Reti, T. On some properties of graph irregularity indices with a particular regard to the s-index. Appl. Math. Comput. 344, 107–115 (2019).

Furtula, B. & Gutman, I. A forgotten topological index. J. Math. Chem. 53(4), 1184–1190 (2015).

Mondal, S. & Das, K. C. Degree-Based Graph Entropy in StructureProperty Modeling. Entropy 25(7), 1092 (2023).

Kulli, V. R. The Gourava indices and coindices of graphs. Ann. Pure Appl. Math. 14(1), 33–38 (2017).

Kulli, V. R. Status Gourava indices of graphs. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research, 11(1), 36770-36773.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of interest. RGP2/245/45.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bayati, J.H.H., Mahboob, A., Amin, L. et al. Predictive modeling of asthma drug properties using machine learning and topological indices in a MATLAB based QSPR study. Sci Rep 15, 30373 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07022-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07022-5