Abstract

The fossil record of past climate transitions offers insights into future biotic responses to climate change. Here, we compare shell growth dynamics, specifically linear extension and net calcification rates, of the bivalve Chamelea gallina between Northern Adriatic Sea assemblages from the Holocene Climate Optimum (HCO, 9 − 5 cal. kyr B.P.) and today. This species is a valuable economic resource, currently threatened by climate change and numerous anthropogenic stressors. During the HCO, regional sea surface temperatures were warmer than today, making it a potential analog for exploring ecological responses to increasing seawater temperatures predicted in the coming decades. By combining standard aging methods with reconstructed sea surface temperatures, we observed a significant reduction in linear extension and net calcification rates in warmer HCO assemblages. During the HCO, immature C. gallina specimens developed a denser shell at the expense of a linear extension rate, which was significantly lower than modern specimens. This resulted in an average delay of 3 months in reaching sexual maturity, which is currently reached after 13–14 months or at a length of ~ 18 mm. This study sheds light on the natural range of variability of C. gallina over longer time scales and its potential responses to near-future global warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Studies on the capacity of marine organisms to acclimatize or adapt to temperature changes have increased during the past few decades as the severity of climate warming has been recognized1,2,3,4,5,6. Some coastal areas have experienced changes in mean seawater temperature, in some cases equal to or greater than the conditions originally predicted by future ocean scenarios1,2,3,4,5.

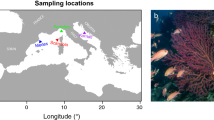

The venus clam Chamelea gallina has been recently used as a model organism for evaluating adaptation responses to near-future environmental changes7,8. This species is abundant in shoreface settings at depths ranging from 0 to 12 m up to 1–2 nautical miles in the Mediterranean Sea9. It is particularly abundant in the western Adriatic Sea (Mediterranean Geographical Subarea—GSA 17), where the massive outflow of the Po (along with that of other minor rivers) and the anticlockwise currents in the North Adriatic Sea (NAS) provide, along the Italian coasts (and particularly around and south of the Po Delta), abundant nutrients, particles, and organic matter10. Moreover, C. gallina represents an economically and ecologically important species in this basin, and its harvesting in GSA 17 accounts for over 98% of ’venus clams’ production at the national level11. Previous studies have mainly focused on population dynamics, shell growth, and composition of this species in living populations of the western Adriatic coasts12,13,14,15,16. It has been observed that the shell properties of C. gallina populations are influenced by environmental changes, with variations in shell density, thickness, and growth primarily related to varying water temperatures and secondarily to salinity and food availability along a spatial gradient12,13. Along the latitudinal gradient in the Adriatic Sea, shells of the warmest populations were characterized by lighter, thinner, more porous, and fragile morphotypes12. However, a solid understanding of long-term biotic dynamics in the context of major environmental shifts is required to reduce the uncertainty regarding organismal responses to ongoing and near-future climate (and derived environmental) changes. Nevertheless, detecting long-term population dynamics in field-based ecological studies can be time-prohibitive. Temporally well-resolved (i.e., low time-averaged) fossil-rich assemblages retrieved in sedimentary successions might record ecological responses to past climatic-driven environmental shifts, far beyond the limited timescales of direct ecological monitoring, typically restricted to the most recent decades17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Given their extensive fossil record, marine calcifying organisms are unique recorders of past environmental changes24,25,26,27,28,29. In particular, bivalve shells record historical data due to their seasonal deposition of carbonate material, retaining high-resolution long-term temporal records of the ambient physical and chemical conditions during growth30,31,32. C. gallina holds significant, yet largely untapped, potential in this regard. Despite its ecological and economic importance, the use of C. gallina dead assemblages to reconstruct millennial-scale intraspecific dynamics in relation to climate change remains virtually unexplored. To date, only one study (Cheli et al.,33) investigated the long-term variability in shell microstructural features—specifically, bulk density, microporosity, and micro-density—in response to past climate-driven environmental changes, comparing Middle and Late Holocene assemblages with modern counterparts from the NAS. That study found that modern assemblages displayed less dense and more porous shells than fossil ones, likely due to lower present-day aragonite saturation states. While Cheli et al.33 focused on shell microstructure and mineralogical properties, the present study uniquely investigates growth performance metrics—specifically, linear extension and net calcification rates—during the Holocene Climate Optimum (HCO) and today, in the NAS south of Po Delta. Here, we aim to evaluate how warming temperatures during the HCO, a potential analog for near-future climate conditions, affected growth dynamics compared to the present day. To this end, we estimated linear extension and net calcification rates on four of five shoreface-related C. gallina assemblages previously investigated in Cheli et al.33 : two from the present-day NAS (namely MGO and MCE; Fig. S1) and the two from the HCO (i.e., CO1 and CO2, respectively dated 7.6 ± 0.1 ky B.P., and 5.9 ± 0.1 ky B.P.; Fig. S1), when regional sea surface temperatures were higher than today (see supplementary material “Environmental Parameters”).

This study addresses the knowledge gap concerning the natural range of variability of C. gallina at temporal scales beyond those typically considered in ecological monitoring, providing valuable insights into the potential responses of C. gallina to near-future global warming.

Results

Specimen age-length von Bertalanffy growth curve

In all examined assemblages, there is no significant difference in the extrapolated ages of fossil and modern C. gallina specimens between estimations based on external and internal rings (Mann-Whitney U test, p > 0.05). Moreover, Kimura’s likelihood ratio tests indicated no significant differences between the growth curves obtained from the external and internal rings. Therefore, a generalized VBGF curve was obtained for each assemblage using the combined data (Fig. 1; Fig. S2). Measurements of stable oxygen isotopes (δ18O) validated the extrapolated ages from the aging methods by fitting the VBGF curves (Fig. 1).

Von Bertalanffy growth curves. The generalized age-length curve for each assemblage is presented alongside the specimen lengths associated with maturity. The von Bertalanffy curves were created by merging data from the two aging methods (counting external and internal rings). Diamonds represent the ages obtained from the δ18O profiles along the shell growth axis and validate the counting aging methods by fitting the curves.

Differences in the observed values for the estimated mean asymptotic specimen length (Linf) (anterior-posterior) and the growth constant (k) in the targeted assemblages were not statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis test, df = 3 and p > 0.05; Table 1). Shell length and estimated life span were comparable among assemblages for mature and all shells (Kruskal-Wallis test, df = 3 and p > 0.05; Table 2). The age at the onset of sexual maturity resulted higher in the warmer HCO assemblage (i.e., + 28% in CO1) compared to modern ones, thus showing a delay in reaching sexual maturity in the former (Kruskal-Wallis test, df = 3 and p < 0.05; Table 2).

Specimen linear extension and net calcification parameters

In each assemblage, the examined shell growth parameters (i.e., linear extension and net calcification rates) were negatively correlated with shell age (Fig. 2). Linear extension and net calcification rates differed significantly among assemblages (Table 2; Fig. 3). Bulk density was significantly different for immature specimens and hence for the whole dataset among assemblages (Table 2; Fig. 3; Fig. S3). The variation of the two above-mentioned growth parameters was then analyzed in relation to temperature-driven changes between the HCO and the present day. Linear extension rate and net calcification rate showed a significant but moderate negative correlation with SST in the whole dataset (rS = -0.311 and − 0.292, respectively, p < 0.001; Fig. 3). Correlations with the SST were also performed separately for immature and mature specimens, with both sub-datasets exhibiting a significant negative correlation for linear extension and net calcification rates (Fig. 3). The two assemblages positioned at the highest and lowest temperature range over time (i.e., CO1–18.6 °C and MGO–17.1 °C) displayed stronger variations in immature specimens, with a 2.3 mm (~ 18%) per year difference in mean linear extension rate and a 0.47 g/cm2 (~ 15%) per year difference in mean calcification rate and (Table 2; Fig. 3).

Variation of shell growth parameters in relation to different SST (Sea Surface Temperature). Three groups were considered: correlations in all shells, correlations in immature shells (< 18 mm), and correlations in mature shells (> 18 mm). The box colors represent the age of the assemblages, ranging from the oldest fossil horizon (dark grey boxes) to the present-day horizon (white boxes). The boxes indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, the lines within the boxes mark the medians, and the crosses mark the mean values. Black points represent outliers. Different letters indicate statistical differences among assemblages (p < 0.05; the number of clams measured for each assemblage is reported in Table 1). rS, Spearman’s rho coefficient. ***p < 0.001, NS, not significant.

Discussion

The radiocarbon analyses of C. gallina specimens revealed that fossil and modern dead assemblages have a comparable time averaging (i.e., the cumulative amount of time in which individuals forming an assemblage have lived). Radiocarbon dating of seven C. gallina specimens from a nearby shoreface dead assemblage showed an interquartile range (IQR) of 50 years17. Along the same line, the radiocarbon dating of eleven C. gallina specimens from sample CO1 resulted in an IQR of 85 years (Table S1). This suggests that the fossil and modern dead assemblages have accumulated over similar time spans (centuries). As a result, the trends in biomineralization observed in the analyzed assemblages reflect long-term, mediated responses to environmental changes and buffer the results from possible short-term or uncommon environmental perturbations that could have affected a specific cohort of the C. gallina population.

As for C. gallina growth parameters retrieved in this study, and despite the variation in temperature between the Holocene Climate Optimum (HCO) and present-day conditions, the maximum expected length of the population (Linf) and the rate at which it is approached (k) do not show significant changes between fossil and modern assemblages (Fig. S2; Table 1). The estimated mean asymptotic shell lengths (Linf) for fossil and modern assemblages were lower than those reported in previous studies for modern living populations of C. gallina from the Adriatic nearshore settings13,15,34,35,36,37. However, considering the lower confidence interval for Linf observed in the sites around the Po Delta, the modern shells from this study were comparable with the modern ones from Mancuso and collaborators29. The observed values of von Bertalanffy growth constants (k) for all assemblages were consistent with nearly almost all previous data obtained in the Adriatic Sea13,34,38.

A lower Linf, but the same k suggests that while individuals in one population will not grow as large as those in another, they grow at a comparable rate during their life span. This could be influenced by a combination of environmental, genetic, and ecological factors that limit the maximum achievable size without affecting the intrinsic growth rate. On a decadal scale, the specimens of the present study might have lived in conditions of lower nutrient availability and higher competition for resources (i.e., higher density)39which affected the Linf value but not their intrinsic growth rate. Thus, at a broad scale (specimen life span), our results support the general physiologic decrease in linear extension rates (and also net calcification rates) as a function of specimen age observed in mollusks and other organisms40,41. For example, in living specimens of C. gallina retrieved along the targeted sector of the NAS13the linear extension rate of C. gallina decreased with increasing age, highlighting fast growth in the first year of life, with a reduction of around 20% in the second year and around 40% in the third year. Hence, the power-shaped relation between growth parameters and age is confirmed in dead assemblages from modern NAS and HCO samples (Fig. 1). This suggests that the overall growth dynamics did not change even when temperatures were higher (1.5 °C) than present-day and comparable to temperature estimates forecasted for the NAS in the next few decades (i.e., before the end of this century)42.

Significant differences in growth patterns emerge when data are analyzed at the subgroup level, especially during the juvenile phase. During the HCO, C. gallina occupied warmer northern Adriatic waters where fluvial influence was limited due to the estuarine configuration of the Po and other rivers. Fossil shells from these horizons are consequently denser and display lower linear extension and net calcification rates than modern shells from sites south of the Po Delta, which now experience strong freshwater input (Fig. S1; Table 2). From a thermodynamic point of view, higher temperatures generally promote CaCO3 deposition by decreasing the energetic costs of shell formation with an increasing aragonite saturation state43. Our data suggest a possibly higher saturation state scenario in the NAS during the Holocene; such a scenario favors the precipitation of a denser shell in warmer seawater conditions. Similarly, the net calcification rates of C. gallina during the HCO are significantly depressed during the juvenile and mature stages of life. So, at present, juvenile clams in the investigated area may be allocating more energy towards faster growth (linear extension rate) at the expense of skeletal density to reach size at sexual maturity. Comparatively, juvenile specimens of C. gallina from the HCO reached maturity with a delay of around three months, with respect to the modern juvenile specimens that attained maturity after thirteen-fourteen months in the NAS29. This delay could represent an important factor for the near-future management of this economically valuable resource. Higher temperature usually coincides with greater and faster gonadal development in bivalves, although this is mainly due to a greater amount of food ingested44. However, a previous study conducted on the clam Ruditapes philippinarum found that at higher temperatures (18 °C respect to 14 °C), the calm had a lower ingestion rate. This led to a negative energy balance, causing slower gonadal development that takes place at the cost of the animal’s energy reserves44. This behavior could explain the growth pattern of C. gallina in HCO due to physical factors dependent on a warmer sea (influencing the aragonite saturation state), combined with lower nutrient run-off from the Po River (with respect to present-day).

It is also interesting to note that within the same study area, we have been assisting in the last centuries to a generally decreasing trend in predator-prey interactions, especially between shell-drilling gastropods and their molluscan prey, as testified recently by Zuschin and colleagues on slightly deeper (prodelta) environments from the same targeted area45. Here, an unprecedented (relative to the Holocene) increase in dimension and population of Varicorbula gibba (another infaunal bivalve) was observed, and it was hypothesized to be driven by ecological release from predation45. Thus, the recent removal of predators (naticids) also feeding on C. gallina and other mollusks46 might have released C. gallina and favored those populations characterized by a faster linear extension rate to reach sexual maturity faster. Conversely, denser shells retrieved in C. gallina specimens from HCO can provide a buffer against drilling predators47 and could also lead to a selective advantage, especially during their juvenile stages, where predation is frequent. However, this resulted in an overall decrease of linear extension rates in C. gallina that lived in a warmer Adriatic Sea, thus taking more time to reach the maturity size.

In addition and based on the current knowledge of the main limiting factors acting on this species’ growth and the results obtained by C. gallina cohorts that lived mainly during the early HCO, we can discuss the principal factors affecting C. gallina populations in the near future, that is seawater temperature and nutrients.

Low tolerance to high seawater temperatures. Previous studies highlighted the relatively low tolerance of C. gallina to high temperatures compared with other bivalve species, showing a great influence on the overall physiological responses and heavy stress conditions when exposed to high temperatures, demonstrating that temperature could be a tolerance limit for this species48,49,50. Indeed, specimens of C. gallina exposed to high summer temperatures (28 °C) showed reduced energy absorption and increased energy expenditure via respiration, negatively affecting the energy balance48 and probably growth, as found during the summer season (temperature > 27 °C) in specimens from the eastern coast of Spain36. Generally, reduced summer growth is concentrated in low temperate zones, particularly in water bodies where bivalves are limited in their northward range migration, such as the Adriatic, due to their low tolerance for high seawater temperatures51. Moreover, oxygen depletion due to high temperatures may harm the clam’s physiological performance, as observed in the bivalve Ruditapes decussatus52. This study evaluated the growth patterns of C. gallina in a warmer context than present-day conditions (~ 1.5 °C); this would imply for HCO longer time, especially during summer seasons where temperatures could have intercepted the threshold of suboptimal growth, thus depressing linear extension rates of C. gallina during the summer season. Following42the mid-twenty-first century climate scenario for the northeast Adriatic region depicts an increase in sea surface temperatures reaching + 3.5 °C in summer and early autumn42. Thus, C. gallina growth should be strongly negatively affected by climate warming during the summer, given that present-day summer average SST temperatures (June-September) in the targeted portion of the Adriatic are 25–26 °C. Therefore, C. gallina could show a strong contraction (> 90%) of its distributional range well before the end of the century7.

Nutrient supply. The growth of C. gallina is also affected by the concentration of the available food supply, as is the case for all filter-feeding organisms53,54. Chlorophyll concentration is a good food proxy for clams, based on the assumption that phytoplankton is the main component of suspension-feeding bivalves’ diet55. Nowadays, the northern area of the western Adriatic basin is characterized by the presence of Po River run-off, which makes the NAS a eutrophic area with the highest average primary production and Chlorophyll a concentration in the Adriatic basin13,56. The higher growth rates of C. gallina found in present-day assemblages thus could also result from the current high food availability compared to past environmental settings of HCO, where, especially for early HCO, the geomorphologic setting of the study area was completely different. Indeed, wide estuaries with lagoon barrier systems developed along the targeted coastal areas57. Thus, the modern study area shows a river-influenced delta where the freshwater and nutrient-rich plumes mix with nearshore marine waters. Early HCO settings were characterized by estuarine settings with barrier island/lagoon complexes, where freshwater input was mainly mixed within the estuaries and lagoons57. Thus, sampled shoreface settings showed a reduced fluvial influence. Increasing temperatures will be associated with increased sea level in the coming decades58,59reducing the plumes of nutrient-rich freshwater in the Adriatic, with mixing occurring more within the river outlet.

Together with previous (mainly ecological-based) research, our study suggests that C. gallina can adapt to (limited) environmental changes resulting from human societal development (see also a recent review by Grazioli and collaborators15) and highlights its ability to persist in a scenario of limited global warming in the near future (e.g., ˂ 1.5 °C change relative to present-day conditions in our study area ).

Conclusion

This study analyzed the variation in shell growth (i.e., linear extension and net calcification rates) of the bivalve C. gallina from assemblages from present-day and Holocene Climate Optimum when the SST in the investigated area of the Adriatic Sea was supposedly 1.5 °C higher than today. The comparison between Holocene sub-fossil records and modern assemblages provided insights into the growth dynamics of this bivalve on a millennial temporal scale, overcoming the time limits imposed by laboratory studies. Unlike our previous study (Cheli et al.,33), which examined shell density and porosity in relation to environmental change, this study quantifies explicitly growth dynamics over the organism’s life cycle. We demonstrate for the first time that elevated Holocene Sea surface temperatures coincided with a significant reduction in both linear extension and calcification rates, particularly during early life stages—a finding not previously addressed. Shell growth decreased per unit of time with SST, showing a reduced linear extension rate and calcification in fossil horizons from HCO. Faster linear extension rates and higher calcification rates were found in present-day C. gallina populations. Specifically, the present-day environmental context appears more favorable for C. gallina growth than the HCO. Given that the HCO may serve as an analog of near-future climate-environmental dynamics, we hypothesize that C. gallina will suffer a reduction in growth rate mainly due to climate warming and related environmental changes. Further investigation into the genetic variability of C. gallina in HCO assemblage and living populations along the latitudinal gradient in the Adriatic Sea could give insights into a selection of morphotypes more adapted to warmer waters and provide a better understanding of the local adaptation of this species in the face of anthropogenically derived climate warming.

Materials and methods

Study area and sampling

The NAS is a semi-enclosed, shallow basin characterized by a wide shelf with a low topographic gradient of 0.02° and an average depth of 35 m59. It extends approximately 350 km southward from the Gulf of Trieste and is bordered westward by Italy and eastward by the Balkan Peninsula. The coasts along the Adriatic western (Italian) sector are primarily sandy and strongly influenced by the Po River outflow, which affects the water circulation in the northern Adriatic Sea and plays a fundamental role in the bio-geochemical processes of the basin60,61. The Po is the largest Italian river, and currently, it supplies over 50% of freshwater input to the NAS62 and about 20% of the total river discharge in the Mediterranean Sea63. However, the Adriatic sedimentary succession records major changes in the basin configuration in relation to the last glacial-interglacial transition64,65,66. During the early Holocene Climate Optimum (HCO, 9–7 cal. kyr B.P.), the north-western Adriatic coast was characterized by estuary systems bounded seaward by a series of lagoons that limited riverine plumes into the Adriatic Sea57. By contrast, during the last part of the HCO (i.e., between 7.0 and 5.0 cal. kyr B.P.), the area transitioned firstly to a wave-dominated and, after 2.0 cal. kyr B.P., to a river-dominated deltaic system57. The last geomorphologic configurations led to the progressively increasing influence of the riverine processes that control present-day coastal dynamics and storage-release of sediments and nutrients. The enhanced freshwater discharge in the nearshore area, especially during the last millennia, resulted in a strong progradation and the upbuilding of the modern Po Delta57.

Our analysis focused on four C. gallina assemblages reported by33 and grouped in two specific time intervals: (1) the HCO (at ~ 7.6 and ~ 5.9 kyr cal. B.P.) documented in subsurface cores and (2) the present day represented by the surficial dead assemblages of the NAS (Fig. S1). Details on age determination methods, sampling design, specimen collection and preparation, and an estimate of environmental parameters can be found in33with a brief description provided in the supplementary material.

Age determination of C. gallina specimens

The specimen’s age was estimated in a subsample of 30 shells of different sizes in each assemblage using three aging methods: shell surface growth rings, shell internal rings, and (partly) stable oxygen isotope composition (Fig. 4). The growth curves were obtained by counting the total number of visible external and internal rings in each examined valve and then fitted with the von Bertalanffy growth function (VBGF): \(\:{L}_{t}=\:{L}_{inf}[1-{e}^{-k\left(t\right)}]\)

Lt is the individual length (the maximum distance on the anterior-posterior axis) at age t, Linf is the asymptotic length (the maximum expected length in the population), k is the growth constant, and t is the specimen’s age. Hence, two growth curves for each specimen belonging to a studied assemblage were produced, and a chi-square test of maximum likelihood ratios was used to examine the significance of differences in growth functions between the two aging methods. If differences are present between VBGF curves from valve external and internal ring counting methods, the growth curve will be based on internal ring counting, which is considered more reliable14. Whereas, if no differences are revealed between VBGF curves from the two-counting methods, a generalized growth curve will be constructed for specimens of each assemblage by merging the growth curves from both methods (Table 1; Fig. 1; Fig. S2). The resulting generalized VBGF curves were used to extrapolate the age in all the other shells by applying the inverse of the generalized VBGF:

To validate the data from the two aging methods and the generalized VBGF curves, δ18O measurements on three valves per assemblage were carried out at the Stable Isotope Biogeochemistry Laboratory, Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, Washington University in St Louis (MO-USA). δ18O measurements were performed on “spot” samples collected from the prismatic and cross-lamellar layers of the shell, sequentially drilled along the growth axis using a single diamond drill (Fig. 4). The δ18O values were plotted against the distance from the umbo, producing a sinusoidal pattern that reflects seasonal temperature variation (Fig. 4). The value closest to the umbo was taken as the starting point (year 0), corresponding to a specific season depending on the δ18O value (e.g., maximum for winter, minimum for summer, or intermediate for spring/autumn). One full year of growth was defined as a complete seasonal cycle in the isotopic curve (e.g., from winter to winter or from summer to summer). Subsequent years were counted by identifying these repeating seasonal cycles. The age-length key obtained from this isotope-based method was plotted alongside the age-length key from the two aging methods (Fig. S2).

Shell ageing methods. (a) external growth rings on the surface of C. gallina after shell scanning; (b) internal growth rings in the shell section; (c) samples of C. gallina with drilling “spots” from the umbo to the ventral edge to determine δ18O values along the shell growth axis; d) sinusoidal sequence of lower (summer, red arrows) and higher (winter, blue arrows) δ18O values recorded by the shells.

Determination of linear extension and net calcification parameters

In C. gallina specimens, linear extension rates were obtained from the valve length/age ratio (cm y− 1), while the net calcification rate (mass of CaCO3 deposited per year per unit area, g cm-2 y− 1) was calculated for each valve by applying the formula: bulk density (g cm− 3) x linear extension rate (cm y− 1). The bulk density of each valve examined in our study was sourced from the literature (see Table 2 in33). Correlation analyses between linear extension rates, net calcification rates, and SST were performed to test for any significant relationship developed over geological time as a function of temperature-driven environmental changes. Differences in the growth of C. gallina specimens were also examined in relation to sexual maturity, which is reached at around 18 mm in modern times15to account for potential variations in the biomineralization process during different stages of the bivalve’s life cycle.

Statistical comparison of shell parameters among assemblages

Since assumptions for parametric statistics were not fulfilled, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test was used to test for differences in shell parameters among assemblages, followed by Dunn’s post hoc tests. Mann–Whitney U tests were applied to determine the differences between ages obtained from external and internal growth rings within each assemblage. For each assemblage, the age-length functions were fitted with the VBGF using a non-linear model, which estimated the VBGF parameters through bootstrapping. Kimura’s likelihood test was then used to compare VBG functions among assemblages. Regarding age in each assemblage, logarithmic regression models were fitted to shell bulk density, while linear models were fitted to linear extension and net calcification rates. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rho) was used to evaluate trends between shell growth parameters and sea surface temperature. All statistical analyses were computed using RStudio software66.

Data availability

The codes and dataset generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Wootton, J. T., Pfister, C. A. & Forester, J. D. Dynamic patterns and ecological impacts of declining ocean pH in a high-resolution multi-year dataset. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 18848–18853 (2008).

Kroeker, K. J. et al. Interacting environmental mosaics drive geographic variation in mussel performance and predation vulnerability. Ecol. Lett. 19, 771–779 (2016).

Wootton, J. T. & Pfister, C. A. Carbon system measurements and potential Climatic drivers at a site of rapidly declining ocean pH. PLoS One. 7, e53396 (2012).

Wahl, M. et al. A mesocosm concept for the simulation of near-natural shallow underwater climates: the Kiel outdoor benthocosms (KOB). Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. 13, 651–663 (2015).

Hofmann, G. E. et al. High-Frequency dynamics of ocean pH: A Multi-Ecosystem comparison. PLoS One. 6, e28983 (2011).

Ninokawa, A., Saley, A., Shalchi, R. & Gaylord, B. Multiple carbonate system parameters independently govern shell formation in a marine mussel. Commun Earth Environ 5 (1), 273 (2024).

Gallagher, K. & Albano, P. Range contractions, fragmentation, species extirpations, and extinctions of commercially valuable molluscs in the mediterranean Sea—a climate warming hotspot. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 80, 1382–1398 (2023).

Moschino, V. et al. Biochemical composition and reproductive cycle of the clam Chamelea gallina in the Northern Adriatic sea: an after-10-year comparison of patterns and changes. Front Mar. Sci 10, 1158327 (2023).

Froglia, C. Fisheries with hydraulic dredges in the Adriatic Sea, p 507–524. Caddy, JF (Ed.), Marine Invertebrates Fisheries: Their Assessment and Management. (1989).

Orban, E. et al. Nutritional and commercial quality of the striped venus clam, Chamelea gallina, from the Adriatic sea. Food Chem. 101, 1063–1070 (2007).

Scarcella, G. & Cabanelas, A. M. Research for pech committee-the clam fisheries sector in the EU-the Adriatic Sea case. (2016).

Gizzi, F. et al. Shell properties of commercial clam Chamelea gallina are influenced by temperature and solar radiation along a wide latitudinal gradient. Sci. Rep. 6, 36420 (2016).

Mancuso, A. et al. Environmental influence on calcification of the bivalve Chamelea gallina along a latitudinal gradient in the Adriatic sea. Sci. Rep. 9, 11198 (2019).

Bargione, G. et al. Age and growth of striped Venus clam Chamelea gallina (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Mid-Western Adriatic sea: A comparison of three laboratory techniques. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 807 (2020).

Grazioli, E. et al. Review of the scientific literature on biology, ecology, and aspects related to the fishing sector of the striped Venus (Chamelea gallina) in Northern Adriatic sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 1328 (2022).

Carlucci, R. et al. Fluctuations in abundance of the striped venus clam Chamelea gallina in the Southern Adriatic sea (Central mediterranean sea): knowledge, gaps and insights for ecosystem-based fishery management. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 34, 827–848 (2024).

Fitzgerald, E., Ryan, D., Scarponi, D. & Huntley, J. W. A sea of change: tracing parasitic dynamics through the past millennia in the Northern Adriatic. Geology 52 (8), 610–614 (2024).

Kidwell, S. M. Biology in the Anthropocene: Challenges and insights from young fossil records. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 4922–4929 (2015).

Pfister, C. A. et al. Historical baselines and the future of shell calcification for a foundation species in a changing ocean. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 283, 20160392 (2016).

Scarponi, D., Azzarone, M., Kowalewski, M. & Huntley, J. W. Surges in trematode prevalence linked to centennial-scale flooding events in the Adriatic. Sci. Rep. 7, 5732 (2017).

Tomašových, A. et al. Ecological regime shift preserved in the anthropocene stratigraphic record. Proc. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 287, 20200695 (2020).

Finnegan, S. et al. Using the fossil record to understand extinction risk and inform marine conservation in a changing world. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 16, 307–333 (2024).

Nawrot, R., Zuschin, M., Tomašových, A., Kowalewski, M. & Scarponi, D. Ideas and perspectives: human impacts alter the marine fossil record. Biogeosciences 21, 2177–2188 (2024).

Bemis, B. E., Spero, H. J., Bijma, J. & Lea, D. W. Reevaluation of the oxygen isotopic composition of planktonic foraminifera: experimental results and revised paleotemperature equations. Paleoceanography 13, 150–160 (1998).

Chauvaud, L. et al. Shell of the great scallop Pecten maximus as a high-frequency archive of paleoenvironmental changes. Geochemistry Geophys. Geosystems 6, Q08001 (2005).

Rhoads, D. & Lutz, R. Skeletal growth of aquatic organisms: biological records of environmental change. (1980).

Schöne, B. R. & Gillikin, D. P. Unraveling environmental histories from skeletal diaries — Advances in sclerochronology. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 373, 1–5 (2013).

Vihtakari, M. et al. A key to the past? Element ratios as environmental proxies in two Arctic bivalves. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 465, 316–332 (2017).

Posenato, R., Crippa, G., de Winter, N. J., Frijia, G. & Kaskes, P. Microstructures and sclerochronology of exquisitely preserved lower jurassic lithiotid bivalves: Paleobiological and paleoclimatic significance. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 602, 111162 (2022).

Klein, R. T., Lohmann, K. C. & Thayer, C. W. Sr Ca and 13C12C ratios in skeletal calcite of Mytilus trossulus: covariation with metabolic rate, salinity, and carbon isotopic composition of seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 60, 4207–4221 (1996).

Schöne, B., Tanabe, K., Dettman, D. & Sato, S. Environmental controls on shell growth rates and δ18O of the shallow-marine bivalve mollusk Phacosoma Japonicum in Japan. Mar. Biol. 142, 473–485 (2003).

Purroy, A., Milano, S., Schöne, B. R., Thébault, J. & Peharda, M. Drivers of shell growth of the bivalve, Callista chione (L. 1758) – Combined environmental and biological factors. Mar. Environ. Res. 134, 138–149 (2018).

Cheli, A. et al. Climate variation during the holocene influenced the skeletal properties of Chamelea gallina shells in the North Adriatic sea (Italy). PLoS One. 16, e0247590 (2021).

Arneri, E., Froglia, C., Polenta, R. & Antolini, B. Growth of Chamelea gallina (Bivalvia: Veneridae) in the Eastern Adriatic (Neretva river estuary). Tisucu Godina Prvoga Spomena Ribarstva U Hrvata. 597, 669–676 (1997).

Deval, M. C. Shell growth and biometry of the striped venus Chamelea gallina (L) in the Marmara sea, Turkey. J. Shellfish Res. 20, 155–159 (2001).

Ramón, M. & Richardson, C. A. Age determination and shell growth of Chamelea gallina (Bivalvia: Veneridae) in the western Mediterranean. Marine Ecology Progress Series 89, 15–23 Preprint at (1992). https://doi.org/10.2307/24831804

Gaspar, M. B. Age and growth of Chamelea gallina from the Algarve Coast (Southern Portugal): influence of seawater temperature and gametogenic cycle on growth rate. J. Molluscan Stud. 70, 371–377 (2004).

Polenta, R. Observations on growth of the striped Venus clam Chamelea gallina L. in the middle adriatic. Bologna, IT: bachelor of science degree. University Bologna, 1–61 (1993).

Peterson, C. & Beal, B. Bivalve growth and higher order interactions: importance of density, site, and time. Ecology https://doi.org/10.2307/1938198 (1989).

Sebens, K. P. The ecology of indeterminate growth in animals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 18, 371–407 (1987).

Caroselli, E. et al. Relationships between growth, population dynamics, and environmental parameters in the solitary non-zooxanthellate scleractinian coral Caryophyllia inornata along a latitudinal gradient in the mediterranean sea. Coral Reefs. 35, 507–519 (2016).

Branković, Č., Güttler, I. & Gajić-Čapka, M. Evaluating climate change at the Croatian Adriatic from observations and regional climate models’ simulations. Clim. Dyn. 41, 2353–2373 (2013).

Clarke, A. Temperature and extinction in the sea: a physiologist’s view. Paleobiology 19, 499–518 (1993).

Delgado, M. & Pérez Camacho, A. Influence of temperature on gonadal development of ruditapes philippinarum (Adams and reeve, 1850) with special reference to ingested food and energy balance. Aquaculture 264, 398–407 (2007).

Zuschin, M. et al. Anthropocene breakdown of predator-prey interactions in the northern Adriatic Sea. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences in press (2024).

La Perna, R. Fori Di predazione Da naticidi Sui bivalvi Della spiaggia Di Catania. Lavori Della Società Italiana Di Malacologia. 24, 177–202 (1992).

Kardon, G. Evidence from the fossil record of an antipredatory exaptation: Conchiolin layers in corbulid bivalves. Evol. (NY). 52, 68–79 (1998).

Moschino, V. & Marin, M. G. Seasonal changes in physiological responses and evaluation of ‘well-being’ in the Venus clam Chamelea gallina from the Northern Adriatic sea. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 145, 433–440 (2006).

Monari, M. et al. Effects of high temperatures on functional responses of haemocytes in the clam Chamelea gallina. Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 22, 98–114 (2007).

Matozzo, V. et al. First evidence of Immunomodulation in bivalves under seawater acidification and increased temperature. PLoS One. 7, e33820 (2012).

Killam, D. E., Matthew, E. & Clapham Identifying the ticks of bivalve shell clocks: seasonal growth in relation to temperature and food supply. Palaios 33 (5), 228–236 (2018).

Sobral, P. & Widdows, J. Influence of hypoxia and anoxia on the physiological responses of the clam ruditapes decussatus from Southern Portugal. Mar. Biol. 127, 455–461 (1997).

Häder, D. P., Kumar, H. D., Smith, R. C. & Worrest, R. Effects of solar UV radiation on aquatic ecosystems and interactions with climate change. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 6, 267–285 (2007).

Arneri, E., Giannetti, G. & Antolini, B. Age determination and growth of Venus verrucosa L. (Bivalvia: Veneridae) in the Southern Adriatic and the Aegean sea. Fish. Res. 38, 193–198 (1998).

Gillikin, D. P. et al. Strong biological controls on sr/ca ratios in Aragonitic marine bivalve shells. Geochemistry Geophys. Geosystems 6, Q05009 (2005).

Gilmartin, M., Degobbis, D., Revelante, N. & Smodlaka, N. The mechanism controlling plant nutrient concentrations in the Northern Adriatic sea. Int. Revue Der Gesamten Hydrobiol. Und Hydrographie. 75, 425–445 (1990).

Amorosi, A. et al. Three-fold nature of coastal progradation during the holocene eustatic highstand, Po plain, Italy – close correspondence of stratal character with distribution patterns. Sedimentology 66, 3029–3052 (2019).

Vermeer, M. & Rahmstorf, S. Global sea level linked to global temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 21527–21532 (2009).

Anthony, E. et al. Delta sustainability from the holocene to the anthropocene and envisioning the future. Nat. Sustain. 7, 1235–1246 (2024).

Poulain, P. M. Adriatic sea surface circulation as derived from drifter data between 1990 and 1999. J. Mar. Syst. 29, 3–32 (2001).

Marini, M., Jones, B. H., Campanelli, A., Grilli, F. & Lee, C. M. Seasonal variability and Po river plume influence on biochemical properties along Western Adriatic Coast. J Geophys. Res. Oceans 113, C05S90 (2008).

Degobbis, D., Gilmartin, M. & Revelante, N. An annotated nitrogen budget calculation for the Northern Adriatic sea. Mar. Chem. 20, 159–177 (1986).

Russo, A. & Artegiani, A. Adriatic sea hydrography. Sci. Mar. 60, 33–43 (1996).

Amorosi, A., Colalongo, M., Fusco, F., Pasini, G. & Fiorini, F. Glacio-eustatic control of continental-shallow marine Cyclicity from late quaternary deposits of the southeastern Po plain, Northern Italy. Quat Res 52, 1–13 (1999).

Gamberi, F. et al. Compound and hybrid clinothems of the last lowstand Mid-Adriatic deep: processes, depositional environments, controls and implications for stratigraphic analysis of prograding systems. Basin Res. 32, 363–377 (2020).

RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Preprint at. (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study partially fulfills the requirements for a PhD thesis of A. Cheli, the PhD Course of Innovative Technologies and Sustainable Use of Mediterranean Sea Fishery and Biological Resources (FishMed-PhD) (University of Bologna, Italy). This work was supported by (1) the European Union–NextGenerationEU through the Italian Ministry of University and Research under Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza (PNRR): Mission 4 Component C2, Investment 1.1 “Conservation of life on Earth: The fossil record as an unparalleled archive of ecological and evolutionary responses to past warming events” code 2022WEZR44; (2) the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4 - Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n.3175 of 18 December 2021 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU. Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP J33C22001190001, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center - NBFC”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C., A.M., S.G., and D.S.: designed the research and collected data; A.C., A.M. and A.R. wrote the initial draft and performed analyses. A.C., A.M., F.P., A.R., G.F., S.G., and D.S. contributed to the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheli, A., Mancuso, A., Prada, F. et al. Chamelea gallina growth declined in the Northern Adriatic Sea during the Holocene Climate Optimum. Sci Rep 15, 23353 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07023-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07023-4