Abstract

Health literacy is crucial for influencing health behaviors and outcomes; however, its development in China has been hindered by the lack of effective measurement tools and conceptual models. This study aimed to evaluate health literacy among Chinese residents using the HLS19-Q47 and construct a health literacy model. A cross-sectional survey was conducted in Guangzhou from February to June 2023 involving 4047 participants. Data were collected on demographics, health literacy, education, socioeconomic status, health behaviors, and self-rated health. Descriptive statistics, logistic regression, and structural equation modeling were used to analyze associations and construct an empirical model. Results showed that only 23.7% of participants had sufficient health literacy. Age, education, and socioeconomic status significantly influence health literacy. Higher health literacy and participation in health education were associated with a lower likelihood of smoking, higher levels of physical activity, and more regular health checkups, but were not significantly associated with alcohol consumption. The findings underscore the applicability of HLS19-Q47 in China and the importance of targeted health education and socioeconomic support in improving health literacy and promoting positive health behaviors. The study establishes an empirical model of health literacy, providing a foundation for interventions to enhance public health in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The regional office for Europe of the World Health Organization (WHO) defined health literacy as a connection with literacy that involves an individual’s knowledge, motivation and competencies to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information to make informed judgments and decisions about healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion in their daily lives to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course1. As academic interest in health literacy continues to grow, an increasing body of research highlights its role as a foundational element in shaping health promotion policies and programs. Health literacy measurement tools are essential for assessing health status, guiding behavior change, promoting self-reflection, and comparing group-level differences—key components for effective individual health management2.

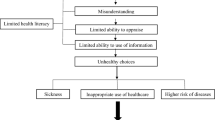

Currently, scholars have used health literacy to construct theoretical models that clarify the intricate association between health literacy and health outcomes and identify the factors that affect health literacy. The literature proposes several theoretical models. For example, one of the most commonly cited models is the “Newest Vital Sign” model, which focuses on how health literacy is related to health outcomes3. The “Interactive Health Literacy” model highlights the interaction between individuals and their environment and suggests that health literacy is not solely an individual’s characteristic but is also influenced by external factors such as the availability of health information and resources4. Moreover, the “Health Literacy and Self-Management” model emphasizes the function of health literacy in self-management behaviors such as medication adherence and healthy lifestyle choices, suggesting that individuals with higher health literacy are more inclined to interact with such behaviors5. However, to apply these theories in practice, it is essential to measure health literacy accurately.

Through a literature search, we have identified 47 health literacy assessment tools, which can be categorized into four types: comprehensive assessment tools, skills assessment tools, disease-specific assessment tools, and population-specific assessment tools6. Comprehensive assessment tools, such as the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire1, evaluate multiple aspects of an individual’s health literacy. Skills assessment tools, such as the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults7 and Health Literacy Skills Instrument8, evaluate an individual’s ability to perform specific health-related skills. Disease-specific assessment tools, such as the Diabetes Health Literacy Scale9, assess an individual’s capability to comprehend and manage health-related information about a particular disease or condition. Population-specific assessment tools, such as the Childhood Health Literacy Scale, are designed to evaluate the health literacy of specific populations10.

The most widely used questionnaire for long-term monitoring and comparing health literacy among the general and specific populations is the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS19-Q47) proposed by the International Coordination Center (ICC) of WHO Action Network on Measuring Population and Organizational Health Literacy (M-POHL)11. At present, this scale has been widely used in Europe, Asia, and South America as a metric of health literacy and to facilitate cross-country comparisons1,12,13. The HLS19-Q47 is a self-report tool that assesses perceived difficulty in 47 tasks related to health care, disease prevention, and health promotion at four stages (access, understand, appraise, and apply) of information processing. The tool employs a scale ranging from “very easy” to “very difficult” to evaluate both individual skills and the fit between personal competencies and the complexity of the situation1.

Since the release of the HLS19-Q47, scholars worldwide have utilized it as a standard tool for measuring health literacy and conducting research across diverse populations. A European study utilizing the HLS19-Q47 revealed substantial differences in health literacy levels among countries. At least 12% of the participants had deficient health literacy, and nearly 50% had limited health literacy, with a large variation in levels among countries (29–62%)1. The survey data showed a socioeconomic gradient in health literacy, with those of lower social status, education, economic deprivation, and younger ages having more individuals with low health literacy. The study also used the Newest Vital Sign (NVS)-Test, a validated objective measure of health literacy3, for comparison and validation, and found similar results to the general index of HLS19-Q47. Previous studies using HLS19-Q47 have indicated that low health literacy is linked to adverse health status1,14, increased healthcare service utilization, longer hospital stays1,15, and higher mortality rates15,16. Moreover, low health literacy has been linked to unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, inadequate physical activity, and reduced use of preventive care services17,18,19. Thus, HLS19-Q47 is a mature and widely used tool for measuring health literacy among populations internationally.

While health literacy is crucial for personal and societal health, its development is slow in China, especially in the measurement tools. In the past, Chinese scholars have extensively researched health literacy using the Chinese Citizens Health Literacy Questionnaire (CCHLQ) for residents, devised by the Chinese Health Education Center20. However, this questionnaire has limitations as it comprises 80 items and is limited to individuals under the age of 69, restricting its application and expansion to 21. Meanwhile, due to language barriers, the CCHLQ is only used in China and has not been promoted to other countries, making it difficult to compare and research health literacy levels among nations. Therefore, it is crucial to use a comparable health literacy scale to measure the level of health literacy in China and construct a health literacy empirical model.

At present, no scholars in mainland China have used HLS19-Q47 to study health literacy. Although the HLS19-Q47 has been applied in Taiwan12, slight differences in the language environment and cultural context between Taiwan and mainland China make the Taiwanese version of the HLS19-Q47 not applicable in China. Therefore, before conducting this study, our team invited five translation experts to translate the HLS19-Q47 into Chinese, followed by back-translating it for accuracy. We also adapted the questionnaire culturally through a small-scale survey. The Chinese version of the HLS19-Q47 passed the accuracy and clarity assessment by 21 experts and professors in different fields. Finally, we conducted a large-scale survey in China to evaluate the reliability and validity of the HLS19-Q47, concluding that it can serve as an important tool for assessing the health literacy of Chinese residents and enabling comparisons with other countries21.

Previous studies by Chinese researchers often develop empirical models based on an established conceptual framework. However, these models are limited by issues in variable specification and theoretical refinement. To address these limitations, the present study proposes the Health Literacy Empowerment Model (HLEM), which integrates key determinants of health literacy, including health education, health behaviors, self-rated health, and socioeconomic status, into a comprehensive framework that spans health outcomes, self-management, and health promotion. Building upon existing theoretical and statistical evidence, this study adapts the HLEM to an individual level in the context of Guangzhou, China, using HLS19-Q47 as the primary assessment tool. In this model, health literacy is defined as an individual’s ability, with socioeconomic status and health education serving as external determinants. Self-rated health is used as an indicator of health outcomes, and health behaviors reflect self-management practices. This refined approach enhances both theoretical clarity and empirical relevance in health literacy research.

Given the complexity of the relationships among multiple latent variables and observed variables in HLEM, the traditional regression model itself is insufficient to capture the entire range of the dynamics among the variables. Therefore, in this study, in addition to using the regression model to analyze the correlation between variables, the Structural Equation Model (SEM) is also adopted to evaluate the measurement properties of the configuration and investigate the structural relationship between the variables at the same time. This method is conducive to a more comprehensive understanding of the interactions among different factors within the proposed framework.

The arrangement of this article is as follows. We first explored the association between demographic factors and health literacy. We then examined the connections between health education and socioeconomic status with health literacy and self-rated health status. We also analyzed the associations between health literacy and health education and health behaviors (including alcohol consumption, smoking, physical activity, and health check-ups), as well as the relationships between these behaviors and self-rated health status. Finally, we utilized SEM to construct HLEM.

Methods

Data collection

This cross-sectional study was conducted between February 25, 2023, and June 10, 2023, to collect demographic data and responses to the HLS19-Q47 from the participants. Using a random sampling method, 3 regions from the 11 administrative regions of Guangzhou were selected as research samples. Subsequently, 1–2 streets were randomly selected within each district, followed by the random selection of 1–2 communities within each street. Within the selected communities, convenience sampling was used to recruit eligible residents.

To ensure representativeness, the study aimed to balance the gender ratio (1:1) as much as possible. Based on health statistics guidelines, the required sample size for surveys is typically 10–20 times the number of questionnaire items. Given that the HLS19-Q47 consists of 47 items, a minimum of 470 valid responses was targeted. Investigators were recruited via advertisements posted on WeChat, specifying that applicants must be college students. The recruitment goal was to engage at least one investigator or team per district. Investigators received online training through Tencent Meeting, covering data collection procedures, questionnaire administration, and quality assurance protocols.

To ensure data quality, a survey team was established to assess participant eligibility and assist individuals who encountered difficulties completing the questionnaire. The survey was conducted using a stratified sampling method across the selected districts, streets, and communities. Investigators invited participants to complete an anonymous electronic questionnaire at their workplace, school, community, or other convenient locations. All participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: The study included Chinese citizens who were permanent residents of Guangzhou, aged 18 years or older, and residing in the city for at least 11 months annually. Participants were required to provide informed consent before taking part. Individuals with cognitive or communication impairments, those unable to comprehend the questionnaire, or those who had previously participated in similar studies were excluded.

This study was performed by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Nanfang Hospital, China (No. NFEC-2022-491). All participants gave written informed consent before participating in the survey.

Variables

This paper utilized self-rated health as a proxy variable for health outcomes. Participants were requested to assess their overall health over the past year utilizing the response options of 1(very bad) to 5 (very good), following WHO recommendations22. Self-rated health is a well-established measure of individual health status and covers mental, physical, and social aspects of health23. It has high test–retest reliability24 and predicts mortality, morbidity, and emotional well-being25. Additionally, self-rated health can provide comprehensive insight into a community’s social well-being and health trajectories over time26.

Health literacy was assessed using standardized HLS19-Q47 index scores calculated with the (Mean-1) × (50/3) formula12. The final sample was divided into four groups based on their health literacy levels: inadequate (0–25 points), problematic (> 25–33 points), sufficient (> 33–42 points), and excellent (> 42–50 points)27. Our group had previously translated the questionnaire into Chinese and used it to assess the health literacy of Chinese residents, with good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.947). In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.978.

We used two dimensions to measure the external environment: health education and socioeconomic status. Health education was measured by asking if the respondents received health education in the past year in various areas, such as occupational disease prevention, infectious disease prevention, reproductive health, chronic disease prevention, mental health, self-rescue in public emergencies, and others. Socioeconomic status was measured by self-rated economic status and social status, with responses ranging from very poor to good.

We obtained health behavior data by querying participants on their alcohol consumption, smoking, physical exercise, and health check-ups. We classified alcohol consumption into low or no alcohol and weekly alcohol, smoking into non-smoking or quit smoking and current smoking, physical exercise into almost no exercise and regular exercise every week, and health check-ups into no regular examination and yearly examination or more.

We also collected the demographic characteristics of the participants: gender, age, residence, and education level. Table 1 provided information on the observed variables collected from the questionnaire items.

Statistical analysis

Data cleaning and analysis were performed using STATA17.0. Descriptive statistics were employed to explore the variables, including number, frequency, mean, and standard deviation. And we employed ordered logistic regression models to examine the associations of health education and socioeconomic status with both health literacy and self-rated health. Subsequently, binary logistic regression was conducted to explore the associations among health education, health literacy, and health behaviors. We then applied ordered logistic regression again to assess the relationship between health literacy and self-rated health, both overall and stratified by urban–rural subgroups. Finally, we employed SEM using IBM SPSS AMOS 26 to test the HLEM. This model was designed to capture the complex relationships among key constructs, including health literacy, health education, health behaviors, socioeconomic status, and self-rated health. The SEM was estimated using the maximum likelihood method. To assess the adequacy of model fit, we used a range of standard goodness-of-fit indices: the chi-square statistic (χ2), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), normed fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and comparative fit index (CFI).

Results

Descriptive statistics

The study analyzed a total of 4047 participants (mean [SD] age, 39.71 [11.44] years), of whom 2646 (65.4%) were male and 1400 (34.6%) were female (Table 1). Most of them (73.3%) were married (including married, divorced, and widowed), lived in urban areas (74.3%), and had received Chinese higher education (82.1%). About one-fifth (18.2%) drank alcohol weekly, nearly one-third (31.9%) were current smokers, and most (82.6%) had an annual physical. The mean (SD) scores of self-rated social status, economic status, and health were 2.97 (0.62), 2.64 (0.95), and 3.52 (0.68), respectively. More than half (52.1%) had received health education in the past year. Only 959 (23.7%) had sufficient or excellent health literacy, while 76.3% had inadequate or problematic health literacy.

Regression results

We conducted ordered logistic regression analyses, with the results presented in Table 2. The analyses indicated significant positive associations between health education and both health literacy and self-rated health. Before adjusting for covariates, residents who had received health education had significantly higher odds of reporting better health literacy (OR 1.689, 95% CI 1.500–1.903), and better self-rated health (OR 1.298, 95% CI 1.153–1.461). These associations remained statistically significant after controlling for covariates including age, gender, marital, resident, and education, indicating the stable and robust influence of health education on both outcomes.

In addition, self-rated economic status was significantly and positively associated with both health literacy and self-rated health. For each one-unit increase in self-rated economic status was associated with higher odds of reporting better health literacy (OR 1.618, 95% CI 1.466–1.786) and better self-rated health (OR 1.801, 95% CI 1.623–2.000). Similarly, higher self-rated social status was also positively associated with both outcomes, each one-level increase corresponded to higher odds of reporting better health literacy (OR 1.525, 95% CI 1.429–1.626) and better self-rated health (OR 1.604, 95% CI 1.500–1.715). These associations also remained significant after adjusting for covariates including age, gender, marital, resident, and education.

A series of binary logistic regression models were employed to examine the associations between health education, health literacy, and health behaviors, with the results presented in Table 3. The analysis showed that an increase in health literacy by one level was associated with a 0.731-fold (95% CI 0.662–0.808) decrease in the odds of smoking. This association remained significant after adjusting for covariates, indicating a stable inverse relationship between health literacy and smoking behavior. Health education and health literacy were not significantly associated with alcohol consumption, and this non-significant relationship persisted after controlling for covariates. In contrast, health education showed a strong positive association with physical exercise. Residents who had received health education were 1.721 times (95% CI 1.465–2.022) more likely to engage in regular physical exercise compared to those who had not, and this association remained stable after adjusting for covariates. Similarly, health education and health literacy were both positively associated with participation in health check-ups. Residents who had received health education were 2.236 times (95% CI 1.861–2.685) more likely to undergo regular health check-ups, while those with a one-level increase in health literacy were 2.088 times (95% CI 1.735–2.513) more likely to do so. These associations also remained significant after controlling for covariates.

Using an ordered logistic regression model (see Table 4), we found that health literacy was significantly and positively associated with self-rated health. Specifically, for each one-unit increase in health literacy, self-rated health increases by 0.705 units (p < 0.001). This association remained statistically significant after adjusting for covariates including socioeconomic status, age, gender, marital, resident, and education. Subgroup analyses by urban–rural residence further revealed that, among urban residents, each one-unit increase in health literacy was associated with a 0.181-unit (p < 0.001) increase in self-rated health, among rural residents, the corresponding increase was 0.183 units (p < 0.001).

The goodness of fit of the models

We introduced the Health Literacy Empowerment Model, which centers on health literacy and comprehensively considers the relationships between socioeconomic status, health education, health behaviors, and health outcomes, creating a systematic theoretical framework. And we considered self-rated health as a measure of health outcomes, and health behaviors as means of self-management. After obtaining the statistical results from Tables 2, 3, and 4, we proceeded to conduct a SEM analysis. We assessed the goodness of the model using the GFI, AGFI, RMSEA, NFI, IFI, and CFI. The results showed that the model fitted the samples well (χ2 = 204.554, GFI = 0.987, AGFI = 0.960, RMSEA = 0.063, NFI = 0.879, IFI = 0.903, CFI = 0.902, p < 0.001).

SEM analysis

The SEM results revealed multiple significant pathways linking socioeconomic status, health education, health literacy, health behaviors, and self-rated health showed in Fig. 1. Socioeconomic status had a strong positive association with both health literacy (β = 0.25, p < 0.01) and self-rated health (β = 0.21, p < 0.01). Health education was positively associated with health literacy (β = 0.18, p < 0.01), exercise (β = 0.08, p < 0.01), and participation in health check-ups (β = 0.09, p < 0.01). Health literacy was negatively associated with smoking (β = − 0.05, p < 0.01) and positively associated with check-ups (β = 0.04, p < 0.01), and self-rated health (β = 0.176, p < 0.01). Among health behaviors, exercise (β = 0.08, p < 0.01), check-ups (β = 0.07, p = 0.02), and smoking (β = − 0.05, p = 0.03) were all significantly associated with self-rated health. These findings suggest that health education and socioeconomic status influence self-rated health both directly and indirectly through improved health literacy and positive health behaviors.

Discussion

We examined the Chinese population using the HLS19-Q47 questionnaire, performing logistic regression analyses to assess the influence of health education and socioeconomic status on health literacy, as well as the association of health literacy and health education with health behaviors and self-rated health. The SEM was employed to construct the empirical HLEM.

The NVS is a widely recognized, objective instrument for measuring health literacy, with good consistency and validity28. Previous studies have compared the measurement results of HLS19-Q47 and NVS and found a high correlation between the two1. Our research also showed that HLS19-Q47 has good consistency and validity (Cronbach’s α = 0.978) when applied in China. In 2018, scholars used NVS to measure the level of health literacy among Chinese residents and found that health literacy was affected by age and education level28. Our utilization of HLS19-Q47 measurement results revealed that health literacy was not only affected by age and education level, but also by gender, marital status, and residence, which was consistent with other studies using HLS19-Q4727.

The survey using HLS19-Q47 found that 23.7% of residents had sufficient health literacy, while the CCHLQ in 2022 was 27.8%. However, the interviewees of CCHLQ were limited to those under 69 years old, while this survey, included a proportion of elderly people over 60 years old (5.2%) and over 69 years old (0.9%), with the oldest person being 84 years old. As health literacy is known to decrease with increasing age, the lower measurement of health literacy using HLS19-Q47 in this study compared to CCHLQ may be owing to the age distribution within the study population.

In 2015, HLS19-Q47 was widely used internationally. In the health literacy survey of European countries, it was found that 29% of residents in the lowest health literacy level countries had sufficient health literacy, with an average health literacy level of 33.5% across eight countries1. In the same year, the health literacy measurement result in Japan using HLS19-Q47 was 25.3%29. These countries had much higher health literacy levels than those in China. The HLS19-Q47 assessment tool is influenced by both an individual’s abilities and contextual factors, such as national health cultures, the complexity/clarity of national healthcare systems, the history of national information and media campaigns, and national/regional health policies.

An unexpected finding in our logistic regression analysis was the confounding relationship between health literacy, health education, and alcohol consumption, which disagrees with previous literature. This may be partially explained by the enduring cultural influence of alcohol in China. Historically, alcohol use transitioned from a means of sustenance to a ritualistic practice over 5,000 years ago30, eventually becoming a social norm and a symbol of compliance in a politically driven context31. Consequently, cultural and political factors may attenuate the potential impact of health literacy and education on alcohol-related behaviors.

In this study, a new Health Literacy Empowerment Model (HLEM) tailored to the Chinese context was developed using SEM, integrating elements from the NVS, Interactive Health Literacy and Self-Management models. The capacity of an individual to competently navigate health-related information and services, defined as health literacy, was affected by external factors such as health education and socioeconomic status. Self-rated health was considered an output of health outcomes, and health behavior was viewed as a tool for self-management. Despite the slightly different results of SEM and logistic regression analysis, both were used in this study. Logistic regression was conducted to analyze manifest variables while SEM paid more attention to the situation of latent variables. Single-path analysis was performed using logistic regression to select the required variables, while multi-path analyses were completed using SEM to deal with more complex situations.

Health education is a critical aspect of good public health programs32, and this study found that participation in health education can significantly improve health literacy (β = 0.18). Although health education was recognized as an important source of health-related information, the extent of its impact on health literacy was rarely confirmed. Scholars tended to focus more on the impact of individual education level on health literacy while overlooking the significance of health education. Although scholars recognized health literacy as the primary objective of health education33, health education studies mostly focus on patients and health technicians34, while others were strategic studies to provide health education according to individual health literacy35,36. Based on survey data of Chinese residents using the HLS19-Q47, this study found a significant association between health education and higher levels of health literacy.

Previous studies have shown that health education can improve clinical outcomes, such as glucemic control in diabetes37, alleviate menopausal symptoms38, and reduce smoking among adolescents and patients with chronic diseases39. However, in our study the results of both the logistic regression and the SEM clearly indicated that there was no significant relationship between health education and smoking in the past year. This discrepancy may be due to differences in motivation. Although both models suggest a positive association between health education and self-rated health, the strength and significance of this relationship differ. In the logistic regression model, the association is statistically significant. However, in the SEM, the direct path from health education to self-rated health is not statistically significant. This discrepancy may be due to the nature of SEM, which is designed to evaluate a comprehensive network of relationships, including both direct and indirect effects among multiple variables. In the SEM, the effect of health education on self-rated health is likely mediated through health-related behaviors such as exercise, and check-ups. Therefore, while a direct effect was not observed in the SEM, a total effect may still exist.

Our study identified a significant correlation between health literacy and health behaviors. Higher health literacy was associated with lower smoking rates, greater participation in physical activity, and more frequent health check-ups. These findings suggested that improving health literacy could be an effective strategy for addressing health-risk behaviors and promoting healthier lifestyles. A positive correlation between good health literacy and improved self-rated health was also observed40, which was consistent in the urban–rural subgroup analysis. This may be explained by the fact that individuals with higher health literacy were more likely to engage in healthier behaviors and adopt healthier lifestyles41. It could be inferred that individuals with higher levels of health literacy possess the knowledge and skills necessary to make informed health decisions, which is associated with better health behaviors and outcomes.

This paper also considered broader socioeconomic factors that may be related to variations in health. Furuya et al.42 utilized demographic data from Japan and reported that health literacy was correlated with self-rated health, independent of residents’ socioeconomic status. However, our study suggested that residents’ health literacy was positively correlated with their socioeconomic status, rather than functioning as an independent correlate of self-rated health. This interpretation is supported by the SEM results, which indicated a stronger direct effect of socioeconomic status on self-rated health compared to that of health literacy. Socioeconomic status was significantly associated with both health literacy (β = 0.25, p < 0.01) and self-rated health (β = 0.21, p < 0.01). While health literacy was also positively associated with self-rated health (β = 0.04, p < 0.01), the effect size was relatively small compared to the direct effect of socioeconomic status. This suggests that health literacy is partially shaped by socioeconomic factors, and its impact on self-rated health may be mediated through health behavior, rather than functioning as a strong independent predictor. Residents with higher socioeconomic status may have more resources and opportunities that are associated with greater access to healthcare and higher levels of health literacy, in turn, which are linked to better self-rated health.

Conclusion

This study made a primary contribution by validating and applying the HLS19-Q47 to assess health literacy in mainland China through a large-scale survey. In addition, it proposed the HLEM based on observed associations among health literacy, health education, behaviors, self-rated health, and socioeconomic factors. The findings suggest that individuals exposed to health education tend to report higher levels of health literacy, which are in turn associated with healthier behaviors and better self-rated health. Socioeconomic status is significantly associated with health literacy and health outcomes, suggesting the need for targeted and context-sensitive public health interventions. Incorporating accessible and diversified health education into public health strategies may help address disparities and equitable health improvement across different population groups. However, as this is a cross-sectional study, the ability to draw causal inferences is limited. Future longitudinal research is warranted to explore the long-term effects of health education on health literacy and health outcomes. In addition, we employed SEM to construct and explore the HLEM. However, as our data are cross-sectional, the SEM results reflect only associational rather than causal relationships. Therefore, any causal interpretations should be made with caution. Moreover, the SEM model was developed based on data from our specific sample, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or settings. Furthermore, given the complexity of health behaviors and the influence of socioeconomic factors, future research should include other variables such as health beliefs, perceived barriers, and social support to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the potential mechanisms of health literacy and its role in public health.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. If any person wishes to verify our data, they may contact the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- HLS19-Q47:

-

The European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire

- NVS:

-

The Newest Vital Sign-Test

- CCHLQ:

-

Chinese Citizens Health Literacy Questionnaire

- M ± SD:

-

Mean ± standard deviation

- SEM:

-

Structural equation modeling

- AGFI:

-

Adjusted goodness of fit index

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- GFI:

-

The goodness of fit index

- NFI:

-

Normed fit index

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

References

Sorensen, K. et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 25(6), 1053–1058. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv043 (2015).

Wernly, B., Wernly, S., Magnano, A. & Paul, E. Cardiovascular health care and health literacy among immigrants in Europe: A review of challenges and opportunities during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Health-Heid 30(5), 1285–1291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01405-w (2022).

Weiss, B. D. et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. Ann. Fam. Med. 3(6), 514–522. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.506 (2005).

Stewart-Lord, A. et al. The use of mHealth apps in interactive health literacy—Perspectives from healthcare professionals. Radiother. Oncol. 161, S1681 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. The roles of social support and health literacy in self-management among patients with chronic kidney disease. J. Nurs. Scholarship 50(3), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12377 (2018).

Fu, Q., Jin, H., Li, L., Ma, Y. & Yu, D. Research status of health literacy assessment tools from the perspective of active health and its enlightenment to China. Chin. General Pract. 25(31), 3933–3943 (2022).

Chisolm, D. J. & Buchanan, L. Measuring adolescent functional health literacy: A pilot validation of the test of functional health literacy in adults. J. Adolescent Health 41(3), 312–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.015 (2007).

Ayre, J., Costa, D. S. J., McCaffery, K. J., Nutbeam, D. & Muscat, D. M. Validation of an Australian parenting health literacy skills instrument: The parenting plus skills index. Patient Educ. Couns. 103(6), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.01.012 (2020).

Moshki, M. et al. Psychometric properties of Persian version of diabetes health literacy scale (DHLS) in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 14(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-022-00923-9 (2022).

Haney, M. O. Health literacy and predictors of body weight in Turkish Children. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 55, E257–E262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2020.05.012 (2020).

Sorensen, K. et al. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 12, 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80 (2012).

Duong, T. V. et al. Measuring health literacy in Asia: Validation of the HLS-EU-Q47 survey tool in six Asian countries. J. Epidemiol. 27(2), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.je.2016.09.005 (2017).

Japelj, N. & Horvat, N. Translation and validation of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q47) into the Slovenian language. Int. J. Clin. Pharm.-Net https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01610-z (2023).

Berkman, N. D., Sheridan, S. L., Donahue, K. E., Halpern, D. J. & Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 155(2), 97–107 (2011).

Vandenbosch, J. et al. Health literacy and the use of healthcare services in Belgium. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 70(10), 1032–1038. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206910 (2016).

Bostock, S. & Steptoe, A. Association between low functional health literacy and mortality in older adults: Longitudinal cohort study. BMJ-Brit. Med. J. 344, e1602. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1602 (2012).

Fernandez, D. M., Larson, J. L. & Zikmund-Fisher, B. J. Associations between health literacy and preventive health behaviors among older adults: findings from the health and retirement study. BMC Public Health 16, 596. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3267-7 (2016).

Jayasinghe, U. W. et al. The impact of health literacy and life style risk factors on health-related quality of life of Australian patients. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 14, 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0471-1 (2016).

Pelikan, J. M. & Ganahl, K. Measuring health literacy in general populations: Primary findings from the HLS-EU Consortium’s Health Literacy Assessment Effort. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 240, 34–59. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-790-0-34 (2017).

Bian, Cy. et al. 2019–2020 in Hubei province rural residents’ health literacy level. China Health Educ. 38(06), 508–510 (2022).

Zhang, M. et al. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Chinese version of the HLS-EU-Q47. Health Promot. Int. 39, 4. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daae083 (2024).

Sun, X. et al. Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the Health Literacy Scale Short-Form in the Chinese population. BMC Public Health 23(1), 385. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15237-2 (2023).

de Bruin, A., Picavet, H. S. & Nossikov, A. Health interview surveys. Towards international harmonization of methods and instruments. WHO Reg. Publ. Eur. Ser. 58, 1–161 (1996).

Jylha, M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 69(3), 307–316 (2009).

Idler, E. L. & Benyamini, Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 38(1), 21–37 (1997).

Ushijima, K., Miyake, Y., Kitano, T., Shono, M. & Futatsuka, M. Relationship between health status and psychological distress among the inhabitants in a methylmercury-polluted area in Japan. Arch. Environ. Health 59(12), 725–731. https://doi.org/10.2307/2955359 (2004).

Schnittker, J. When mental health becomes health: Age and the shifting meaning of self-evaluations of general health. Milbank Q. 83(3), 397–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00407.x (2005).

Sorensen, K. et al. Measuring health literacy in populations: illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health 13, 948. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-948 (2013).

Xue, J. et al. Validation of a newly adapted Chinese version of the Newest Vital Sign instrument. PLoS ONE 13(1), e190721. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190721 (2018).

Nakayama, K. et al. Comprehensive health literacy in Japan is lower than in Europe: A validated Japanese-language assessment of health literacy. BMC Public Health 15, 505. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1835-x (2015).

Cui, L. reveal Chinese customs, Chinese wind, Chinese style, Chinese style of Chinese wine culture. Wine 50(06), 127–131 (2023).

Raninen, J. & Livingston, M. The theory of collectivity of drinking cultures: how alcohol became everyone’s problem. Addiction 115(9), 1773–1776. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15057 (2020).

Larimore, G. W. The elements of health education in good public health programs. Public Health Rep. (1896) 75(10), 933–936. https://doi.org/10.2307/4590962 (1960).

Ploomipuu, I., Holbrook, J. & Rannikmae, M. Modelling health literacy on conceptualizations of scientific literacy. Health Promot. Int. 35(5), 1210–1219. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daz106 (2020).

Akca, A. & Ayaz-Alkaya, S. Effectiveness of health literacy education for nursing students: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 27(5), e12981. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12981 (2021).

Muscat, D. M. et al. Incorporating health literacy in education for socially disadvantaged adults: An Australian feasibility study. Int. J. Equity Health 15, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0373-1 (2016).

Connell, L., Finn, Y. & Sixsmith, J. Health literacy education programmes developed for qualified health professionals: A scoping review. BMJ Open 13(3), e70734. https://doi.org/10.12688/hrbopenres.13386.1 (2023).

Pai, L. W., Chiu, S. C., Liu, H. L., Chen, L. L. & Peng, T. Effects of a health education technology program on long-term glycemic control and self-management ability of adults with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 175, 108785.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108785 (2021).

Pelit, A. S. & Senturk, E. A. Effects of health education and progressive muscle relaxation on vasomotor symptoms and insomnia in perimenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ. Couns. 105(11), 3279–3286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2022.07.015 (2022).

Ismail, I., Sidiq, R. & Bustami, B. The effectiveness of health education using audiovisual on the Santri Smokers’ motivation to stop smoking. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 22(8), 2357–2361. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.8.2357 (2021).

Nie, X., Li, Y., Li, C., Wu, J. & Li, L. The association between health literacy and self-rated health among residents of China aged 15–69 years. Am. J. Prev. Med. 60(4), 569–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.032 (2021).

Furuya, Y., Kondo, N., Yamagata, Z. & Hashimoto, H. Health literacy, socioeconomic status and self-rated health in Japan. Health Promot. Int. 30(3), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat07145 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the International Coordination Center (ICC) of WHO Action Network on Measuring Population and Organizational Health Literacy (M-POHL) for authorizing the translation of HLS19-Q47 for use in China.

Funding

This work was supported by the 2020 National Health Institute Project of the United Kingdom (No. K121363166), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.71974211), the Guangdong Province Key Field Research and Development Plan (No.2019B020227004), the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 21BGL298, 22AGL002), the Major Humanities and Social Sciences Research Projects in Zhejiang Higher Education Institutions (No. 2024QN095), and Zhejiang Gongshang University ‘Digital + ’ Disciplinary Construction Management Project (No. SZJ2022B002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mengjun Zhang conceptualized the paper, analyzed and interpreted the data, and edited the draft. Xiangna Guo and Xiuhua Mao provided insight into the methodology and reviewed and edited the draft. Chao Zuo interpreted and reviewed the data and provided feedback on the manuscript. Xiangna Guo, Xiuhua Mao and Guochun Xiang supervised the development of the manuscript concept and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Wenyuan Li,Dong Xu, Hongwei Zhou and Chao Zuo facilitated project administration and funding management, oversaw the conceptualization of the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Mengjun Zhang and Xiangna Guo have made similar contributions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Nanfang Hospital, China (No. NFEC-2022-491). All participants gave written informed consent before participating in the survey.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M.J., Guo, X., Wang, R.S. et al. Health literacy model integrating health education, health behaviors, self-rated health, and socioeconomic status in the Chinese population. Sci Rep 15, 32320 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07094-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07094-3