Abstract

The purpose of this study was to analyze the longitudinal effects of participation in different categories of sports on the stability, locomotor, and manipulative motor competence domains of children. This study used a prospective cohort design involving 124 participants, including 68 boys and 56 girls, all 6 years old. The study spanned 6 months, with assessments conducted at three time points: baseline, 3 months, and 6 months. The assessments were conducted using the Motor Competence Assessment (MCA) battery, which includes six tests designed to evaluate motor competence across three domains: stability, locomotor, and manipulative skills. Participants were categorized as a cohort based on their regular extracurricular physical activity, specifically in sports classified into four categories: target games, striking/fielding games, net/wall games, and invasion games. A mixed ANOVA was conducted to compare the groups across the three assessment time points for statistical analysis. No significant differences were observed at baseline between groups in the locomotor (p = 0.917; ES = 0.008) or manipulative (p = 0.914; ES = 0.008) domains, but significant differences were found after 3-months (p = 0.045; ES = 0.078), and after 6-months (p < 0.001; ES = 0.209) respectively. No significant differences were noted in the stability domain at any time period (p > 0.05). In conclusion, children engaged in striking/fielding and invasion games demonstrated significant improvements in manipulative and locomotor skills over six months. Specifically, invasion games enhanced locomotor skills, while striking/fielding games improved manipulative skills. These findings highlight the positive and specific impact of diverse sports experiences on motor skill development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Motor competence refers to the proficiency in performing a wide variety of motor skills and movement patterns encompassing locomotor, stability, and manipulative gross motor skills1. This concept is multidimensional, including aspects such as motor coordination, balance, agility, and fine and gross motor skills1. It is hypothesized that high levels of motor competence enable individuals to engage confidently and successfully in diverse physical activities, contributing to overall physical fitness and well-being2. Consequently, motor competence may serve as a foundational building block for physical literacy, a more encompassing concept that integrates the motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge, and understanding necessary to value and maintain lifelong engagement in physical activities, ultimately fostering a positive and sustainable relationship with movement and enhancing well-being and sports participation3.

It is believed that ensuring a proper motor competence in children is crucial for their overall healthy development, serving as a foundational element for physical, cognitive, and social growth4. Some studies suggest that children with higher motor competence exhibit improved physical health, including better cardiovascular fitness or muscular strength5,6,7. Enhanced motor skills may facilitate greater engagement in physical activities8. Furthermore, proficient motor abilities may contribute to cognitive development by enhancing spatial awareness, problem-solving skills, and academic performance9. Socially, children with better motor competence may experience higher self-esteem and more positive interactions with peers10.

Encouraging motor skill development through structured physical education and sports programs and unstructured play may promote lifelong adherence to physical exercise, establishing a positive feedback loop where improved motor skills lead to more frequent and enjoyable participation in physical activities11. This, in turn, fosters long-term health benefits, including reduced risks of non-communicable diseases12,13,14.

While motor competence generally follows a consistent developmental trajectory regardless of exposure to specific contexts or adherence to particular sports and games15 it is speculated that these factors may influence certain domains of motor competence, such as stability, manipulative, and locomotor skills16. For example, net sports such as tennis and volleyball may require greater engagement in drills and activities related to the manipulative and stability domains17. On the other hand, invasion games, including soccer or basketball, can be particularly effective at developing all three domains of motor competence since they demand advanced locomotor skills for running and quick directional changes, manipulative skills for dribbling or passing, and stability skills for maintaining balance and control during dynamic play18.

A cross-sectional study compared preschoolers enrolled in regular sports programs with those who were not. It was observed that participants in sports generally showed significantly better results on the Test of Gross Motor Development-2 compared to non-participants19. In another cross-sectional study involving children aged 8 to 12 years, it was noted that participation in specific types of sports (e.g., open-skill sports, closed-skill sports) influenced their motor skills as measured by the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency-2 Short Form20. Specifically, it was observed differences in motor competence among participants in different types of sports, with closed-skill sports showing favorable outcomes20. More recently, a cross-sectional study comparing participants aged 7 to 19 enrolled in physical education, futsal, volleyball, and ballet revealed differences in motor competence among the groups, with futsal participants generally demonstrating higher scores18.

Interestingly, a longitudinal study found that initial levels of motor competence were associated with continued sports participation after two years, suggesting that motor competence may serve as a catalyst for engaging in sports21. This finding is supported by another longitudinal study which revealed that children with high motor competence performed better on physical fitness tests and participated in sports more frequently. Given that physical fitness levels changed similarly over time between groups, children with low motor competence may be at risk of lower physical fitness throughout their lives16.

While participation in sports is widely encouraged, our understanding of how specific types of sports differentially influence the various domains of motor competence (stability, locomotor, and manipulative) remains limited. Existing research has primarily focused on older children (ages 8–12)20 overlooking the critical and rapid motor development that occurs in the early years when children are first introduced to organized sports. This gap is particularly significant, as early sport experiences may have a profound and lasting impact on motor skill acquisition patterns, and findings from older age groups may not accurately reflect these foundational processes.

To address this gap, this study categorizes sports into four distinct types—target games, striking/fielding games, net/wall games, and invasion games—based on their rules and dynamics22. It is expected that participation in different game categories will elicit specific adaptations in motor competence. For example, the precision and control required in target games are expected to particularly enhance manipulative motor competence, while the dynamic movement and spatial awareness demanded in invasion games are anticipated to foster greater development in locomotor skills. However, longitudinal evidence examining these differential effects from the early stages of sport participation is still lacking.

This study aims to contribute to the field by providing a longitudinal analysis of how specific sport categories impact the development of motor competence domains in early childhood. Unlike prior research that has largely overlooked this critical developmental period, our study will offer crucial insights into the foundational influence of different sport types on motor skill trajectories from the initial stages of engagement. By analyzing sports categorization based on their core elements, this research will provide an understanding of the specific adaptations within the stability, locomotor, and manipulative domains fostered by each category. Thus, purpose of this study was to analyze the longitudinal effects of participation in different categories of sports on the stability, locomotor, and manipulative motor competence domains of children.

Methods

The current study followed the reporting recommendations of The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)23.

Study design

This study is an observational prospective cohort design in which all children were evaluated initially and then tracked for their motor competence development over a period of 6 months based on their adherence to specific sports. Assessments were conducted at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months. Initially, none of the children had prior experience with regular sports; participation began only after this initial evaluation.

Setting

The initial evaluation (baseline) was conducted at the start of formal schooling (Grade 1). Participants were then monitored over a 6-month period, with assessments being conducted at 3 and 6 months following the initial evaluation. The recruitment process began with schools being invited to participate for convenience. Information was then promoted to legal guardians through the schools, who were invited to allow their children to participate. After the initial recruitment, volunteers who had demonstrated interest were screened against the inclusion criteria. Those who met the criteria were evaluated using the Motor Competence Assessment (MCA) tool24. During the 3- and 6- month follow-ups, participant motor competence was analyzed, adherence to structured sports among participants was tracked, and the characteristics of the sport practices was documented.

Participants

The inclusion criteria established for the study were as follows: (i) not currently enrolled in a structured sport at the time of the first evaluation; (ii) being six years old in the year of the study; and (iii) participating exclusively in the sports game categories defined for the study or not enrolled in any structured sport practice. The exclusion criteria were: (i) missing any evaluation sessions (baseline, 3-month, or 6-month); and (ii) experiencing illness or injury during the 6-month observation period that prevented participation in 10% or more of the expected sessions.

Out of an initial pool of 171 potential participants who volunteered for this study, 135 were deemed eligible, while the remaining 36 were unavailable to participate in the assessment sessions and complete the necessary forms and questionnaires over the 6-month period. During the 6-month cohort period, 6 out of the 135 participants missed the second evaluation at 3 months, and an additional 5 missed the third evaluation at 6 months. Consequently, the total number of participants who met all inclusion criteria was reduced to 124.

Of the 124 participants, 68 were boys and 56 were girls and all were 6 years old. The boys had an average height of 120.4 ± 4.7 cm and body mass of 22.8 ± 1.8 kg, while girls measured an average height of 118.8 ± 2.8 cm and body mass of 21.9 ± 1.8 kg. After categorizing them by type of sports, the distribution was as follows: 20 in target games (boys, n = 12; girls, n = 8), 18 in striking/fielding sports (boys, n = 12; girls, n = 6), 28 in net/wall games (boys, n = 11; girls, n = 17), 30 in invasion games (boys, n = 19; girls, n = 11), and 28 in the control group (not enrolled in any sports) (boys, n = 14; girls, n = 14).

The study was approved by Yibin Third People’s Hospital under the code YBSDSRMYY-2024-01. Prior to participation, the study design, risks, and benefits were explained to both participants and their legal guardians. Upon their consent, legal guardians signed a free informed consent form that explicitly detailed the option to withdraw from the study without penalty. The study followed the ethical standards defined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Variables

The study examined the independent variable of participants’ chosen sport types over time. It is important to note that no intervention was carried out by the researchers. The study merely involved monitoring participants’ voluntary participation and adherence to sports. These practices, based on individual decisions, were tracked and assessed through questionnaires. For clarity in data aggregation, sports were categorized into four groups, following the classification of games described by Almond in 198625: target games, striking/fielding games, net/wall games, and invasion games. Target games involve sending an object towards a stationary target to score with fewer attempts than opponents (e.g., archery, bowls, golf). Striking/fielding games focus on placing the ball away from fielders to score runs (e.g., baseball, cricket, softball). Net/wall games entail returning a ball so opponents cannot respond or make errors (e.g., badminton, table tennis, volleyball). Invasion games involve penetrating the opponent’s defensive area to score while defending one’s own goal (e.g., soccer, basketball). To be classified as a practitioner in a specific sport, participants were required to attend at least two training sessions per week dedicated exclusively to that sport, maintaining this practice for over 90% of the observation period (i.e., 6 months). Participants who did not adhere to a structured sport were classified as the control group.

As a cohort study, we recorded participants’ involvement in sports, with their practices occurring at different clubs and in various contexts based on their location and family preferences. In the questionnaires completed by their parents, information was collected regarding the sport, frequency per week, and weekly practice duration, ensuring that participants engaged in a similar amount of practice within the same sport. No changes in the participants’ sports were observed throughout the study. The following list outlines the sports observed within each category: Target games (archery, n = 20); Striking/fielding games (baseball, n = 10; softball, n = 8); Net/wall games (badminton, n = 18; table tennis, n = 6; volleyball, n = 4); and Invasion games (soccer, n = 21; basketball, n = 9).

The study’s dependent variables included outcomes from the MCA24specifically percentiles achieved on six tests: jumping sideways, shifting platforms, shuttle run change of direction, standing long jump, throwing ball velocity, and kicking ball velocity. Additionally, scores were calculated for participants across various motor competence domains: stability (including scores from the sideways jumping and shifting platform tests), locomotor skills (including the shuttle run, change of direction, and standing long jump tests), and manipulative skills (including tests for ball throwing velocity and kicking velocity).

Data sources/measurement

Data assessments were conducted in the morning at the same time each week for all three evaluations. This approach ensured consistency in the evaluation context. The assessments took place in an indoor facility. A group of nine evaluators, all with backgrounds in physical education and sports sciences, were trained to administer the MCA tests. A pilot test involving 10 children (not included in this study) was conducted to assess the reliability of observers (both within and between observers), with repeated measures taken at two time points, one week apart. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of observer reliability averaged across the measurements were good (> 0.87 ICC). Students were evaluated in groups, following the same sequence of assessments: (i) demographic information; (ii) anthropometrics; (iii) standardized warm-up protocol (consisting of 5 min of jogging, 3 min of upper limb dynamic stretching, and 3 min of lower limb dynamic stretching); (iv) jumping sideways; (v) shifting platforms; (vi) ball velocity when thrown; (vii) ball velocity when kicked; (viii) standing long jump; and (ix) shuttle run change of direction test.

The MCA, introduced and validated in 201624, served as the instrument for measuring motor competence. This assessment comprises six quantitative motor tasks organized into three interconnected factors. The robustness of the model was confirmed across different samples, showing excellent structural and measurement reliability. Subsequently, the research group provided normative values, enabling the calculation of percentiles based on age and sex15. In 2022, the research team further refined the scoring and classification method for MCA sub-scales and the total score26. An independent research group also verified the reliability of the MCA tests, determining that, except for the jumping sideways task, the tests are reliable and only need to be performed twice instead of three times27.

Supplementary Material 1 provides detailed information on each of the tests administered, while Table 1 summarizes the tests and measures used in the study.

Quantitative variables

The calculation of MCA sub-scales and total scores involved transforming participants’ results in each MCA test into age- and sex-specific normative values (percentiles), as detailed in a previous study28. Following the original article28we organized the six tests into three domains: locomotor (which includes the standing long jump and shuttle run change of direction test), stability (shifting and jumping sideways), and manipulative (ball throwing and kicking).

Additionally, a more recent study26 highlighted that averaging the normative values across age and sex categories for each test enables the computation of MCA sub-scales and total scores. The formula26 applied to calculate each sub-scale (e.g., locomotor, stability, manipulative) was ((LC test 1 / (LC test 1 + LC test 2)) * P test 1) + ((LC test 2 / (LC test 1 + LC test 2)) * P test 2), where LC means loading coefficient and P means percentile value.

Statistical methods

Based on a previous study18 (partial eta squared = 0.07), a power analysis (G*Power, version 3.1.9.6, Universität Düsseldorf, Psychologie – HHU, Düsseldorf, Germany) for a 5-group, 3-measurement repeated measures ANOVA with within-between interaction (effect size f = 0.45, power = 0.95) indicated a required sample size of 25 participants.

The descriptive statistics are presented in terms of mean and standard deviation. Preliminary examination for outliers was completed, followed by tests for normality and homogeneity using Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene’s tests, respectively, both of which confirmed normality (p > 0.05) and homogeneity (p > 0.05) within the sample. A mixed ANOVA was then conducted, incorporating time (baseline, 3-months, and 6-months) and groups (target games, striking/fielding sports, net/wall games, invasion games, and a control group) to explore potential significant interactions. Effect size was assessed using partial eta squared (\(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)). Post-hoc analysis was performed using the Bonferroni test. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.), with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

By monitoring participants’ attendance and adherence to their sports practices, we were able to determine adherence rates over the intervention period for each game category. The observed adherence rates were as follows: Target games (91.3 ± 0.3%, equivalent to approximately 43.8 ± 0.14 sessions attended out of 48), Striking/Fielding games (94.1 ± 1.8%, approximately 45.2 ± 0.86 sessions), Net/Wall games (96.2 ± 2.3%, approximately 46.2 ± 1.10 sessions), and Invasion games (92.6 ± 0.9%, approximately 44.4 ± 0.43 sessions). These values represent both the proportion and the absolute number of sessions attended out of the total scheduled sessions (48 sessions, based on participants attending two sessions per week) for each type of game.

The Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation) of the absolute scores obtained by participants in the five groups across the three evaluation periods. Significant interactions between groups and time were observed in standing long jump (F = 28.265; p < 0.001; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.487), shuttle run (F=13.343; p<0.001; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.310), throwing ball velocity (F=22.611; p<0.001; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.432), and kicking ball velocity (F = 22.146; p < 0.001; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.427), although no significant interactions were observed in jumping sideways (F=0.008; p>0.999; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)>0.999), shifting platforms (F=0.269; p=0.909; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.009).

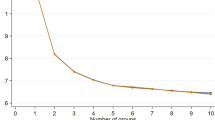

Figure 1 shows motor competence percentiles across different domains during three evaluation periods. Significant interactions between time and groups were observed in the locomotor domain (F = 22.855; p < 0.001; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.434), manipulative domain (F=25.377; p<0.001; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.460), and overall motor competence score (F=19.257; p<0.001; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.393). However, no significant interactions were found in the stability domain (F=0.541; p=0.724; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.018).

Although no significant differences were observed between groups in the locomotor domain at the baseline (F = 0.238; p = 0.917; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.008), significant differences were found after 3-months (F=2.512; p=0.045; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.078), and after 6-months (F=5.636; p<0.001; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.159). In particular, after 6-months, the invasion games were significantly better than the control (p=0.009), net/wall (p=0.010), striking (p<0.001), and target (p = 0.007).

In the manipulative domain, no significant differences between groups were observed at baseline (F = 0.242; p = 0.914; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.008), although significant differences were found after 3-months (F=2.514; p=0.045; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.078), and after 6-months (F=7.848; p<0.001; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.209). Specifically, the invasion games were significantly better than control (p=0.022), net/wall games (p=0.001), and target games (p=0.029), while striking was also significantly better than control (p = 0.006), net/wall games (p<0.001), and target games (p = 0.007).

No significant differences were observed between groups in the stability domain at baseline (F = 0.344; p = 0.848; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.011), after 3-months (F=0.271; p=0.896; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.009), or after 6-months (F=0.177; p=0.950; \(\:{\eta\:}_{p}^{2}\)=0.006).

Discussion

The current prospective cohort study investigated how adherence to structured sports game practices influences the development patterns of motor competence. While no significant differences were found between groups in terms of stability variables during the evaluation periods, children who adhered to striking/fielding and invasion games showed significant differentiation from other groups in manipulative variables after six months. Additionally, children who adhered to invasion games significantly differentiated from other groups in locomotor variables after six months. Participants who adhered to target games and net/wall games maintained motor competence scores similar to those of the control group throughout the observation period.

During the observation period, it was observed that children who participated in soccer significantly improved their locomotor competences compared to their peers in tests such as shuttle run, change of direction, and standing long jump. While the studies reviewed did not analyze developmental trajectories, a previous cross-sectional study found that children involved in futsal generally achieved higher scores than those participating in volleyball or ballet18. Our results can be partly explained by the fact that invasion games (e.g., soccer, basketball) frequently involve rapid changes in direction29quick accelerations and decelerations, and spatial awareness30. These activities demand a coordinated movement and timing31possibly promoting the development of fundamental movement skills such as agility and speed, both crucial for assessments like shuttle run tests that measure change of direction32. Moreover, the dynamic nature of invasion games requires rapid decision-making and spatial orientation skills33contributing to improvements in motor planning and execution. Furthermore, the speed actions and high accelerations or decelerations required in these games enhance lower limb coordination and explosive muscle power34. These attributes can be transferable to performance in tests like the standing long jump, which assess muscular power35,36.

Our findings also indicated that children who participated in both invasion games (e.g., soccer, basketball) and striking/fielding games (e.g., baseball, cricket) demonstrated improved manipulative motor competence over the observation period, especially in tasks involving ball speed during kicking and throwing, compared to those who were involved in target sports, net/wall games, or the control group. This enhancement could be attributed to the specific motor skills demanded by these game types. Invasion games involve frequent ball interactions37requiring players to manipulate it with their feet (e.g., soccer) or hands (e.g., basketball) to achieve specific objectives. This requires proprioception, timing, and accuracy in ball manipulation38possibly contributing to increased ball speed in kicking and throwing tasks. Similarly, striking/fielding games emphasized hand-eye coordination, timing, and force generation for hitting and throwing balls39thereby enhancing manipulative motor skills related to ball speed.

Our results revealed that children who participate in various sports games do not show significant enhancement in stability motor competences when compared to a control group of children who do not adhere to a specific sport. While invasion games and striking/fielding games require dynamic movements and quick adaptations to game situations, they may not necessarily prioritize the static stability and balance in youth stages40 which are required for tests like shifting platforms or jumping sideways. Target sports and net/wall games, on the other hand, often focus on precise movements and accuracy rather than the continuous adjustments to external perturbations that promote stability motor competences. Consequently, children engaged in these sports may not consistently develop the specific balance and stability skills assessed in these motor competence tests. This highlights the specificity of motor skill development in relation to the demands of different sports categories and highlights the importance of targeted training protocols to enhance stability motor competences in children.

While our study provides interesting findings on the influence of adherence to structured sports game practices on motor competence development, several limitations should be acknowledged. One limitation is the six-month observation period, which may restrict our ability to capture long-term effects of sports participation on motor competence trajectories or identify potential plateaus. Future research should incorporate longer follow-up periods to gain a deeper understanding of how these effects evolve over time, especially during critical developmental stages. Moreover, although we observed significant improvements in manipulative and locomotor skills among children engaged in invasion games and striking/fielding games, our study did not investigate potential mediating factors such as socioeconomic status, parental involvement, or school environment, which could impact motor skill acquisition. Moreover, as a convenience sample, we encountered discrepancies in the sex of participants and their enrollment in preferred sports activities. Future investigations should include these variables to clarify their role in shaping motor competence outcomes. Additionally, integrating objective measures of physical activity levels and skill proficiency assessments could strengthen future studies exploring the relationship between sports participation and motor competence.

This study’s prospective cohort design, rather than an experimental setup, limits the ability to directly manipulate variables or establish causal relationships. The cohort design allows for observation of naturally occurring patterns of sport participation and motor competence development, but it also means that other influencing factors, such as personal motivation, psychological engagement, and social aspects of sports participation, were not controlled. These psychological and engagement factors can significantly influence children’s adherence to sports, potentially affecting the development of motor skills. For instance, children’s intrinsic motivation, enjoyment, and perceived competence in a particular sport could impact their level of involvement and effort, thereby influencing their motor skill outcomes. As such, psychological aspects of sport participation, including confidence, self-esteem, and interest in the activity, could mediate how effectively children develop competencies in different domains. Given that the study was observational, future research could benefit from considering these psychological and motivational factors in relation to motor competence development across different sports contexts.

Despite its limitations, our study suggests that adherence to specific sports and environmental conditions can influence various aspects of motor competence. Therefore, it is plausible to hypothesize that exposing children to a variety of sports experiences is beneficial for enhancing their physical literacy and promoting diverse motor skill development. Public policies, schools, and parents may prioritize offering children multiple sports opportunities to expand their skill sets. This approach has the potential to sustain improvements in motor competence over time, encouraging lifelong engagement in physical activity and enhancing overall well-being.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our prospective cohort study investigated the impact of adherence to structured sports game practices on the development patterns of motor competence in children. While no significant differences were observed in stability variables between groups over the six-month evaluation periods, children participating in striking/fielding and invasion games showed significant improvements in manipulative and locomotor skills compared to their peers. Specifically, participants engaged in invasion games demonstrated enhanced locomotor abilities. Similarly, children involved in striking/fielding games exhibited improvements in manipulative skills, underscoring the specificity of motor skill development inherent to these sports. Our findings may suggest that exposing children to diverse sports experiences can foster motor skill development, thereby promoting physical literacy and long-term engagement in physical activity. Future research should explore additional mediating factors and incorporate longer follow-up periods to elucidate the enduring effects of sports participation on motor competence trajectories across different developmental stages.

Data availability

All data is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- MCA:

-

Motor Competence Assessment

- STROBE:

-

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

References

Khodaverdi, Z. et al. Motor competence performances among girls aged 7–10 years: different dimensions of the motor competence construct using common assessment batteries. J. Mot Learn. Dev. 9, 185–209 (2021).

Robinson, L. E. et al. Motor competence and its effect on positive developmental trajectories of health. Sports Med. 45, 1273–1284 (2015).

Lundvall, S. Physical literacy in the field of physical education – A challenge and a possibility. J. Sport Health Sci. 4, 113–118 (2015).

Lopes, L. et al. A narrative review of motor competence in children and adolescents: what we know and what we need to find out. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 18 (2020).

Cattuzzo, M. T. et al. Motor competence and health related physical fitness in youth: A systematic review. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 19, 123–129 (2016).

Haga, M. The relationship between physical fitness and motor competence in children. Child. Care Health Dev. 34, 329–334 (2008).

Hands, B. Changes in motor skill and fitness measures among children with high and low motor competence: A five-year longitudinal study. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 11, 155–162 (2008).

Barnett, L. M., van Beurden, E., Morgan, P. J., Brooks, L. O. & Beard, J. R. Childhood motor skill proficiency as a predictor of adolescent physical activity. J. Adolesc. Health. 44, 252–259 (2009).

Cadoret, G. et al. The mediating role of cognitive ability on the relationship between motor proficiency and early academic achievement in children. Hum. Mov. Sci. 57, 149–157 (2018).

Schmidt, M., Blum, M., Valkanover, S. & Conzelmann, A. Motor ability and self-esteem: the mediating role of physical self-concept and perceived social acceptance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 17, 15–23 (2015).

Abusleme-Allimant, R. et al. Effects of structured and unstructured physical activity on gross motor skills in preschool students to promote sustainability in the physical education classroom. Sustainability 15, 10167 (2023).

Pombo, A. et al. Effect of motor competence and Health-Related fitness in the prevention of metabolic syndrome risk factors. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 95, 110–117 (2024).

Ballin, M. & Nordström, P. Does exercise prevent major non-communicable diseases and premature mortality? A critical review based on results from randomized controlled trials. J. Intern. Med. 290, 1112–1129 (2021).

Katzmarzyk, P. T., Friedenreich, C., Shiroma, E. J. & Lee, I. M. Physical inactivity and non-communicable disease burden in low-income, middle-income and high-income countries. Br. J. Sports Med. 56, 101–106 (2022).

Rodrigues, L. P. et al. Normative values of the motor competence assessment (MCA) from 3 to 23 years of age. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 22, 1038–1043 (2019).

Fransen, J. et al. Changes in physical fitness and sports participation among children with different levels of motor competence: A 2-Year longitudinal study. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 26, 11–21 (2014).

Chagas, D. V., Ozmun, J. & Batista, L. A. The relationships between gross motor coordination and sport-specific skills in adolescent non-athletes. Hum. Mov. 18, 17–22 (2018).

Saraiva Flôres, F., Soares, P., Willig, D., Reyes, R. M., Silva, A. F. & A. C. & Mastering movement: A Cross-sectional investigation of motor competence in children and adolescents engaged in sports. PLoS One. 19, e0304524 (2024).

Queiroz, D. R., Ré, A. H. N., Henrique, R. S., de Moura, M., Cattuzzo, M. T. & S. & Participation in sports practice and motor competence in preschoolers. Motriz: Revista De Educação Física. 20, 26–32 (2014).

Spanou, M., Stavrou, N., Dania, A. & Venetsanou, F. Children’s involvement in different sport types differentiates their motor competence but not their executive functions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 5646 (2022).

Henrique, R. S. et al. Association between sports participation, motor competence and weight status: A longitudinal study. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 19, 825–829 (2016).

Butler, J. How would Socrates teach games?? A constructivist approach. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat Dance. 68, 42–47 (1997).

Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 13, 31 (2019).

Luz, C., Rodrigues, L. P., Almeida, G. & Cordovil, R. Development and validation of a model of motor competence in children and adolescents. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 19, 568–572 (2016).

Almond, L. Reflecting on themes: A games classification. in Rethinking games teaching (eds. Thorpe, R. D., Bunker, D. J. & Almond, L.) 71–72 (Loughborough, UK, 1986).

Rodrigues, L. P., Luz, C., Cordovil, R., Pombo, A. & Lopes, V. P. Motor competence assessment (MCA) scoring method. Children 9, 1769 (2022).

Silva, A. F. et al. Reliability levels of motor competence in youth athletes. BMC Pediatr. 22, 430 (2022).

Rodrigues, L. P., Cordovil, R., Luz, C. & Lopes, V. P. Model invariance of the motor competence assessment (MCA) from early childhood to young adulthood. J. Sports Sci. 39, 2353–2360 (2021).

McBurnie, A. J. & Dos’Santos, T. Multidirectional speed in youth soccer players: theoretical underpinnings. Strength. Cond J. 44, 15–33 (2022).

Phillips, D., Hannon, J. C. & Molina, S. Teaching Spatial awareness is Small–Sided games. Strategies 28, 11–16 (2015).

Čoh, M. et al. Are Change-of-Direction speed and reactive agility independent skills even when using the same movement pattern? J. Strength. Cond Res. 32, 1929–1936 (2018).

Jakovljevic, S. T., Karalejic, M. S., Pajic, Z. B., Macura, M. M. & Erculj, F. F. Speed and agility of 12- and 14-Year-Old elite male basketball players. J. Strength. Cond Res. 26, 2453–2459 (2012).

Rösch, D., Schultz, F. & Höner, O. Decision-Making skills in youth basketball players: diagnostic and external validation of a Video-Based assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 2331 (2021).

Cortis, C. et al. Inter-Limb coordination, strength, jump, and sprint performances following a youth men’s basketball game. J. Strength. Cond Res. 25, 135–142 (2011).

Pandy, M. G. & Zajac, F. E. Optimal muscular coordination strategies for jumping. J. Biomech. 24, 1–10 (1991).

Young, W. B. Transfer of strength and power training to sports performance. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 1, 74–83 (2006).

Grehaigne, J. F., Caty, D. & Godbout, P. Modelling ball circulation in invasion team sports: a way to promote learning games through Understanding. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy. 15, 257–270 (2010).

Boraczyński, M. T., Sozański, H. A. & Boraczyński, T. W. Effects of a 12-Month complex Proprioceptive-Coordinative training program on soccer performance in prepubertal boys aged 10–11 years. J. Strength. Cond Res. 33, 1380–1393 (2019).

Laby, D. M., Kirschen, D. G., Govindarajulu, U. & DeLand, P. The Hand-eye coordination of professional baseball players: the relationship to batting. Optom. Vis. Sci. 95, 557–567 (2018).

Jadczak, Ł., Grygorowicz, M., Dzudziński, W. & Śliwowski, R. Comparison of static and dynamic balance at different levels of sport competition in professional and junior elite soccer players. J. Strength. Cond Res. 33, 3384–3391 (2019).

Funding

The authors have no funding to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XG conceived and designed the analysis, collected the data, performed the analysis, and wrote the paper. CL and JZ, WY and QX collected the data and wrote the paper. AK wrote the paper. FMC conceived and designed the analysis, supervised the study, and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by Yibin Third People’s Hospital under the code YBSDSRMYY-2024-01.

Informed consent

Prior to participation, the study design, risks, and benefits were explained to both participants and their legal guardians. Upon their consent, legal guardians signed a free informed consent form that explicitly detailed the option to withdraw from the study without penalty.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, X., Li, C., Zhao, J. et al. Adherence to different types of sports shapes motor competence development in preschool children. Sci Rep 15, 26130 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07109-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07109-z