Abstract

The presence of pharmaceutical pollutants, such as clonazepam (CZP), in aquatic environments poses significant risks to ecosystems and human health. This study introduces a novel solid-phase extraction (SPE) method utilizing a urea-modified metal-organic framework (MIL-101(Fe)-Urea) for the selective preconcentration and quantification of CZP in environmental water samples, then analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography analysis. The MIL-101(Fe)-Urea adsorbent was synthesized through a post-synthetic modification approach and characterized using FTIR, PXRD, SEM, BET, and EDX techniques. Key extraction parameters, including pH, adsorbent dosage, extraction/desorption times, and sample volume, were optimized to achieve maximum adsorption efficiency. Under optimal conditions, the method demonstrated excellent linearity (R2 = 0.997) within a concentration range of 20–1500 µg L−1, with a low detection limit (LOD = 0.030 µg L−1), high recovery rates (94.9–99.0%), and a relative standard deviation of 1.4%. The developed method was successfully applied to real environmental water samples, confirming its practicality for environmental monitoring. This study highlights the potential of MIL-101(Fe)-Urea as an advanced adsorbent for the analysis of pharmaceutical contaminants, contributing to the development of efficient and environmentally friendly analytical techniques for water quality assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the past decades, pharmaceuticals have been found in aquatic environments, such as rivers, lakes, and sewage treatment plants, at trace concentrations ranging from ng L−1 to µg L−11,2,3. To date, the widespread use of psychotropic drugs and their frequent discovery in various settings have brought significant attention to the effects these substances may have on the environment4. The presence of pharmaceutical residues in aquatic environments can have adverse effects on both human health and aquatic life5.

Benzodiazepines are a class of medications widely used as sedatives, muscle relaxants, hypnotics, and anxiolytics6,7. Clonazepam (5-(2-chlorophenyl)-1, 3-dihydro-7-nitro-2 H-1, 4-benzodiazepin-2-one, CZP) is a common benzodiazepine prescribed for the treatment of epilepsy, seizures, panic disorders, and sleep disturbances in both adults and children8,9,10. The extensive use of psychiatric medications, including clonazepam, has led to their release into the environment through various sources, such as households, hospitals, and wastewater treatment plants11,12. Hospitals, in particular, generate significant amounts of medical waste, including psychiatric drugs and their transformation products, which are discharged through patients’ urine and feces, as well as the improper disposal of expired medications13. This ultimately contributes to the bioaccumulation of these pharmaceuticals in aquatic ecosystems, posing potential risks to environmental and human health.

Headaches and kidney problems are among the adverse effects that humans who drink water contaminated with CZP may experience14,15,16. Furthermore, there is evidence that CZP can have detrimental effects on human health, including degenerative and inflammatory disorders17. Furthermore, other studies indicate that the bioaccumulation of these psychiatric drugs may adversely affect living creatures, leading to endocrine abnormalities and impairing the reproduction, growth, and survival of aquatic microorganisms and animals18. This pharmaceutical chemical and its metabolites have been detected in several water sources, including drinking water, wastewater, surface water, and sewage treatment facilities, at varying amounts (ng/L to µg/L)19.

Trace levels of pharmaceuticals in aquatic habitats pose dangers to ecosystems and human health due to their biological activity and persistence4,20. Regular water treatments cannot effectively remove CZP from drinking water, leading to potential public health concerns. As a result, it is necessary to monitor trace levels of CZP to protect drinking water supplies from contamination and to protect aquatic life from the harmful effects of this drug. Therefore, the development of sensitive and efficient methods for the detection of CZP is crucial. However, due to the complex sample matrix and low concentrations of the analyte in real samples, direct determination is almost impossible. Thus, an extraction / preconcentration step before its instrumental analysis is necessary21.

Solid-phase extraction (SPE) has emerged as a popular technique to preconcentrate and purify analytes from complex matrices. It offers a number of benefits, such as ease of use, quick operation, automation potential, high efficiency and selectivity, and minimal eluent volume usage22,23,24. SPE has been the most frequently used technique to extract several psychotropic drugs from water samples, and it was thoroughly investigated in various settings25,26,27.

Various analytical techniques, including electroanalytical methods28,29UV/Vis spectrophotometry30,31gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy32,33 and high-performance liquid chromatography34,35 have been developed for the quantification of CZP in different matrices. Some employed techniques exhibit disadvantages, including time consumption, high costs, intricate extraction procedures and low sensitivity or restricted linear range. In contrast, the high performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection (HPLC/DAD) procedures are preferred due to their simplicity, cost-effectiveness and reliability, rendering them the optimal alternative for the quantitative analysis and separation of BZDs36,37,38. Some of these previous methodological advancements included unique, expensive columns.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are a class of crystalline hybrid materials composed of metal ions or clusters connected by organic bridging ligands through coordination bonds39,40,41. These materials are renowned for their versatility, tunable porosity, and high surface area42. Due to these properties, MOFs have been extensively studied for various applications, such as separation43chemical sensors44gas storage45catalysis46,47and drug delivery48,49. Among these, iron-based MOFs (Fe-MOFs) are particularly advantageous because of their cost-effectiveness, large surface areas, porous structures, and environmentally friendly characteristics. The performance of MOFs can be further enhanced through various modification strategies50. One particularly effective approach is post-synthetic modification (PSM), which involves the functionalization of MOFs with organic molecules containing specific functional groups that exhibit a higher affinity for target molecules, such as drugs51. By incorporating these functional groups, researchers can precisely tailor the interactions between the MOF and the target drug, enabling optimization of the drug delivery process52. This refined control over drug release mechanisms not only enhances the efficiency of MOFs but also improves the precision and therapeutic potential of drug delivery systems.

Amino-functionalized MOFs, such as MIL-101(Fe)-NH2, have demonstrated significant effectiveness in the adsorption and removal of pharmaceutical pollutants from environmental samples. Notably, the potential of MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 in environmental remediation has been further underscored by its successful application in the adsorption and elimination of tetracycline, a widely used antibiotic, from aqueous solutions53. In another study, Sorafenib was extracted from human plasma and wastewater using the synthesized metal–organic frameworks in a dispersive micro-solid phase, which was subsequently followed by high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet determination54. In another study, the removal of fluoxetine hydrochloride from pharmaceutical wastewater was investigated using nanofiltration membranes loaded with MIL-101(Fe) and MIL-101(Fe)-NH2. Improved filtration performance and contaminant rejection efficiency are demonstrated by the membranes55.

In this study, we synthesized and functionalized porous MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 with 1,4-phenylene diisocyanate to develop a urea-modified MOF (MIL-101(Fe)-Urea) as an effective adsorbent for the SPE of CZP. The urea functionality (-NHCONH-) was covalently introduced into the MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 through the reaction between the NCO groups of 1,4-phenylene diisocyanate and the amino groups in the MOF. The introduction of urea functionalities can not only modify the structural properties of the MOF but also significantly enhance its adsorption performance, rendering it highly effective for the targeted removal of pollutants56. This study represents the first report of using MIL-101(Fe)-Urea as an adsorbent for SPE in the analytical quantification of CZP in environmental water samples. The developed adsorbent showed notable improvements in selectivity, extraction efficiency and sensitivity compared to previously adsorbents.

Experimental

Reagents

HPLC grade methanol and acetonitrile were obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Analytical grade reagents iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3.6H2O), 2-aminoterephthalic acid (H2BDC-NH2), acetone, ethanol, 1,4-phenylene diisocyanate (C8H4N2O2), N, N′-dimethylformamide (DMF), sodium hydroxide, and hydrochloric acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used without further purification. Deionized water was prepared using a Milli-Q purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). A stock standard solution of Clonazepam (1000 mg L−1) was prepared in deionized water. All necessary standard solutions were prepared by appropriate dilution of this stock solution.

Apparatus

The FTIR spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer Spectrum-FT-IR (PerkinElmer, Germany) using KBr pellets. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) were conducted using a MIRA3 Field Emission SEM (TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic) used to examine the morphology and chemical composition of the samples. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were obtained using Cu Kα1 radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) using a Netherlands-made Philips X’Pert XRD diffractometer (Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands). An HPLC system (Knauer, Berlin, Germany) was utilized for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The eluent and mobile phase were passed through the column using a Masterflex Peristaltic Pump (Model No. 7534-04, L/S, Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL, USA). The isocratic mobile phase contained two parts: acetonitrile (70:30 v/v) and phosphate buffer (0.05 mM, pH 3.0) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1. The wavelength of 220 nm57 was set for the UV detector and used to detect CZP. The peak area measurement was used to quantify the CZP, and an external calibration curve was used for quantitative analysis.

Synthesis of MIL-101(Fe)-NH2

MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 MOF was prepared following previously reported procedures58. Typically, 0.675 g (2.497 mmol) of FeCl3.6H2O was dissolved in 7.5 mL of DMF and added to a solution of 0.225 g (1.242 mmol) of H2BDC-NH2 in 7.5 mL of DMF. After thermal treatment in an autoclave for 24 h at 110 °C, the resulting product was recovered by filtration and washed several times with DMF and methanol. Then the obtained solid was finally dried overnight at 60 °C in an oven.

Synthesis of functionalized MIL-101(Fe)-Urea

The MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 (activated, 100 mg, 0.396 mmol NH2) was magnetically agitated in 2.5 mL dry DMF for five minutes at room temperature in an N2 atmosphere. 1,4-Phenylene diisocyanate (176 mg, 1.1 mmol) was dissolved in 5 mL dry DMF while being added drop-wise to the previous suspension before being stirred at 40 °C under an N2 atmosphere for 48 h59. After cooling down to room temperature, acetone was added to the reaction mixture, which was then stirred for 1 h. Then, the solid was separated using centrifugation and repeatedly washed with acetone and ethanol. The collected precipitate was soaked in acetone for 24 h and then separated and dried under reduced pressure following the set-up (at room temperature for 4 h, then at 80 °C for 12 h, and finally at 130 °C for 4 h) to give the desired adsorbent. A schematic illustration of the mechanism and formation of MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 functionalized with 1,4-phenylene diisocyanate is shown in Fig. 1.

SPE procedure

After adding 25.0 mL of the sample solution to a 50 mL vial, the pH of the solution was adjusted to 6.5 using either 0.1 mol L−1 NaOH or 0.1 mol L−1 HCl. Then 10 mg of MIL-101(Fe)-Urea was added and the analyte was extracted onto the sorbent by sonicating for 10 min. To separate the adsorbent from the liquid, the suspension was centrifuged. After discarding the supernatant, 1.0 mL of methanol was added as the elution solvent, and the mixture was sonicated for 5 min. The supernatant was collected by filtering following centrifugation. The methanol was collected, and 60 µL was injected into the HPLC for analysis.

Equation (1) was used to determine the extraction recovery (ER):

Where C0 and Cf are the initial and final concentrations of the CZP, respectively.

Method validation

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) recommendations guided the validation of the analytical approach. Evaluated were parameters including linearity, accuracy, precision, and limit of detection (LOD). Based on preliminary tests, environmental relevance, and HPLC detection capacity, the concentration range (20–1500 µg L−1) was chosen to guarantee consistent detection over expected real-world CZP concentrations. The method’s precision was evaluated by examining standard CZP drug solutions on the same days (intra-day RSD%) and five successive days (inter-day RSD%). Precision and accuracy were evaluated at three concentrations (50, 100, and 200 µg L−1), each measured in triplicate. The method’s limit of detection (LOD) was determined by using the LOD = 3Sb/m formula (Sb represents the standard deviation of signals from 20 consecutive blank measurements, and m denotes the calibration curve’s slope).

Results and discussion

Characterizations of MIL-101(Fe)-Urea

The MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 was synthesized and further functionalized with 1,4-phenylene diisocyanate to create MIL-101(Fe)-Urea. This novel modification involved the formation of urea linkages between the NCO groups of 1,4-phenylene diisocyanate and the NH2 groups in MIL-101(Fe)-NH2, resulting in a crosslinked structure. The powder X-ray diffraction patterns (PXRD) of both before and after the MOF functionalization process are shown in Fig. 2. The patterns demonstrated the recognizable diffraction peaks of 2θ = ~ 9.1°, 10.3°, 16.5°, 18.7 ° and 21.7°, showing a strong correlation with the earlier research60,61. The peak intensities of the MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 and MIL-101(Fe)-Urea are approximately the same, revealing that the MOF kept its crystallinity after modification.

The chemical structure changes of MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 and MIL-101(Fe)-Urea, as revealed by IR spectroscopy, are shown in Fig. 3. The symmetrical and asymmetrical vibrations of the -NH2 group and O-H stretching modes are identified as the absorption band at approximately 3300 cm−162. The distinctive absorption bands at 1576 and 1382 cm−1 are ascribed to the carboxylate groups58,63,64,65,66. The band at 1254 cm−1 linked to the vibration of C-N stretching. The band at 769 cm−1 associated to the C-H bending vibration of the benzene ring of the linker. The FTIR spectrum of the functionalized MOF exhibited a new peak at ~ 1636 cm−1, corresponding to amide (C = O) groups from the urea functionality. Additionally, the amino group peak of the pristine MOF disappeared, while a new band appeared around 3200 cm−1, attributed to the -NH stretching of the urea group. The band at 1216 cm−1 linked to the stretching of C-N in modified MOF. Furthermore, slight shifts in vibration modes were observed, with some moving to higher or lower wavenumbers compared to the pristine MOF. These changes confirm the successful integration of urea with the MOF framework.

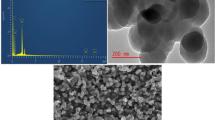

The morphological structures of the studied samples were examined using FESEM analysis. As shown in Fig. 4a and b, MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 presented octahedral crystalline structures with diameters ranging from 220 to 700 nm and an average size of ∼430 nm. In comparison, the functionalized MOF showed a slight alteration in both particle size and morphology compared to the pristine MOF (Fig. 4c,d).

Energy dispersive X-ray elemental analysis (EDX) was also used to examine the elemental composition of MIL-101(Fe)-Urea, revealing the presence of C, O, N, and Fe elements, providing additional evidence of the modified MOF ‘s successful synthesis (Fig. 5). Elemental mapping analysis showed that each element is evenly distributed throughout the entire structure (Fig. 6).

Drug adsorption mechanism

Understanding the adsorption mechanism between the analyte and the adsorbent is crucial for elucidating the interactions responsible for CZP adsorption on the Fe-MOF. To explore this mechanism, we analyzed the surface charge of the adsorbent over a wide pH range, alongside the interactions between CZP and the sorbent. The isoelectric point (pI) of the adsorbent was determined to be 7.2. Below this pH, the protonation of urea groups imparts a positive charge to the sorbent’s surface. This positively charged surface facilitates favorable electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged functional groups of the clonazepam molecule, thereby enhancing adsorption. Conversely, when the pH exceeds the pI, the sorbent’s surface acquires a negative charge, leading to potential repulsion between the similarly charged MOF surface and CZP, thus diminishing adsorption. The adsorption efficiency of MOFs in aqueous solutions is influenced by factors such as pore structure, electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, π-π interactions, and acid-base interactions48,67.

In the case of CZP adsorption onto MIL-101(Fe)-Urea, hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions are the primary mechanisms, as illustrated in Fig. 759. Hydrogen bonds form between the nitro groups of CZP and the urea functionalities in the MOF, while electrostatic interactions occur between the polar regions of CZP and the MOF68,69,70. Another contributing factor is the interaction between the heteroatoms of CZP and the Fe(III) sites in the MOF. It has been proved that urea functionalization improves the stability, selectivity, and capacity factor of the process71,72. The large pore volume and high surface area of MIL-101(Fe)-Urea facilitate these interactions, enabling efficient CZP adsorption. Additionally, π-π interactions between the aromatic rings of CZP and the terephthalic acid linkers in the MOF framework, along with van der Waals forces, further enhances adsorption.

Urea-modified MOFs exhibited significant utility owing to their strong hydrogen bonding capabilities, which enhance their effectiveness in anion recognition and separation73. Furthermore, urea-modified MOFs revealed potential as solid-state, shape-selective organocatalysts74.

Furthermore, it has been shown56,75 that the stability of MIL-101(Fe)-Urea in an aqueous medium can be improve compared to MIL-101(Fe)-NH2. This increasing hydrophobicity can be ascribed to the phenethyl on MIL-101(Fe)-Urea surface after PSM, which reduced its surface energy and resulted in a higher hydrophobicity.

Optimization of the SPE procedure

Parameters that might potentially affect this process, such as the sample solution’s pH value, the amount of MOF adsorbent, the type and volume of the eluent, the extraction and desorption times and the sample volume were examined and optimized in order to obtain the highest SPE extraction efficiency. The one-parameter-at-a-time approach, commonly used in SPE-based extractions using a MOF was used to optimize the impact of these parameters on the extraction recovery. This approach assumes no interaction between the process factors. (i.e., the presence of interaction between the factors of the process was not considered). Optimizations were performed using 25.0 mL of a 1.0 mg L−1 of CZP drug standard solution.

Effect of pH

The pH of the sample solution is one of the most crucial factors influencing SPE; in addition to its other effects, it directly affects the adsorbent’s surface charge. The standard solution’s pH was adjusted within the range of 2.0 to 8.0 in this investigation (Fig. 8). The drug’s maximum sorption capacity occurred at pH = 6.5. The presence of extra H+ ions competing with the drug’s cation groups for the adsorption site is likely the cause of lower adsorption at more acidic pH levels. Reduced adsorption capacity results from further pH increases, which may be caused by a weakening of the electrostatic force of attraction between the oppositely charged adsorbate and adsorbent.

Effect of the amount of adsorbent

To investigate the effect of the MOF sorbent amount on target analyte absorption, the amount of adsorbent was varied between 1.0 and 20.0 mg while all other extraction parameters remained constant. The maximum extraction recovery was achieved at 10.0 mg of adsorbent. Further addition of adsorbent did not significantly increase the extraction recovery (Fig. 9). This suggests that all available active sites on the MIL-101(Fe)-Urea were occupied at 10.0 mg, leading to a constant absorption signal. Consequently, 10.0 mg of adsorbent was chosen for subsequent experiments.

Effect of eluent type and volume of the eluent on CZP recovery

The impact of both eluent type and volume on CZP recovery from the adsorbent was investigated. To efficiently elute analytes from the sorbent, it is crucial to select an eluting solvent capable of completely removing the analyte while minimizing solvent consumption. The effect of eluent type on recovery was explored using 1.0 mL of ethanol, methanol, and acetonitrile. Based on the results (Fig. 10), methanol demonstrated superior extraction efficiency and was selected for further analysis. The influence of eluent volume (0.5 to 2.0 mL) using methanol was subsequently examined. As illustrated in Fig. 11, maximum CZP recovery was attained at 1.0 mL. Increasing the volume beyond this point led to decreased recovery, likely attributed to analyte dilution76. The mobile phase (acetonitrile: phosphate buffer, 70:30 v/v) was considered as a potential eluent; preliminary tests demonstrated that methanol provided higher desorption efficiency for CZP. The use of methanol resulted in greater recovery and reduced matrix interferences, whereas the phosphate buffer in the mobile phase posed a risk of interacting with the MIL-101(Fe)-Urea structure, potentially affecting adsorbent stability.

Effect of extraction time

A range of 5.0 to 20.0 min was used to study the impact of extraction time on extraction recovery. The amount of the adsorbed drug onto Fe-MOF increases with time as CZP molecules interact more with the MOF surface and then penetrate the adsorbent pores until saturation is reached. As shown in Fig. 12, the extraction recovery was increased to 10.0 min and then became constant. Thus, it was determined that the optimum extraction time was 10.0 min.

Effect of desorption time

Desorption time is an important parameter influencing extraction recovery. Complete analyte desorption from the solid phase to the eluent depends on sufficient desorption time. Insufficient time may lead to reduced recovery due to incomplete elution. This study examined desorption times ranging from 1.0 to 20.0 min (Fig. 13). Optimal extraction recovery was achieved at 5 min, indicating near-complete elution of the CZP drug. Therefore, a 5-min desorption time was selected for subsequent analyses.

Effect of sample volume

Another crucial parameter affecting the preconcentration factor in SPE is the sample solution volume. To investigate this, sample volumes ranging from 25.0 to 500.0 mL, each containing 10 mg of analyte were tested. Extraction recovery increased up to 250.0 mL before plateauing (Fig. 14). As can be seen, more analyte can adsorb on the Fe-MOF by increasing the sample solution’s volume; but after a certain volume, equilibrium sets in and extraction recovery decreased. Although there was no significant difference in recovery between 100 and 500 mL, 250.0 mL was chosen as the optimal sample volume to select a reasonable volume of the sample.

Reusability of the adsorbent

To assess the reusability of the MIL-101(Fe)-Urea adsorbent, it was employed for eight consecutive cycles of CZP extraction. After each cycle, the analytes were extracted, and the adsorbent was washed with an eluent solvent. As illustrated in Fig. 15, the recovery percentage (R%) of the analytes showed no significant decline, indicating the excellent reusability of the adsorbent. The stability and functionality of the adsorbent were confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy. The FTIR spectra (Fig. 3) revealed that the MOF retained its structural integrity and functional groups after adsorption, demonstrating its stability and suitability for repeated use.

Method validation results

The developed method’s linearity, detection limit, and precision under optimum conditions were determined and are enumerated in Table 1. The calibration curve was linear between 20 and 1500 µg L−1 and had a determination coefficient (R2) of 0.997 (Fig. 16). The precision of the method was evaluated via intra-day and inter-day relative standard deviations and was found to be 1.4% and 3.1% respectively, which indicate very good repeatability and reproducibility. The LOD determined for this method is 0.03 µg L−1, which further emphasizes the very high sensitivity and accuracy for identification of CZP at trace levels in environmental samples. The robustness of the new process was deliberately evaluated by the critical parameters (variations of ± 5%), including pH, the adsorbent amount, the eluent volume, and the duration of the extraction. The approach demonstrated constant CZP recoveries greater than 90% and precision with a RSD below 5% in these conditions, thus affirming its robustness and reliability for the CZP extraction in significantly modified circumstances. Preventive HPLC chromatograms that illustrate the successful detection and quantification of CZP are presented in Fig. 17.

Real sample analysis

The proposed protocol was employed to assess its reliability and applicability for CZP determination in tap water (Zabol), a well water (Zabol) and wastewater samples. Water samples were analyzed without pre-treatment, while wastewater samples (collected from the urban sewage of Zabol) was filtered through filter paper prior to extraction to eliminate suspended particles. No analyte was identified in the samples; consequently, to examine the influence of the sample matrix on the extraction, samples were spiked at three concentration levels (50, 100, and 200 µg L−1) to evaluate the influence of the sample matrix on analyte extraction. Determination of CZP from real water samples was performed under optimal conditions. The results, presented in Table 2, demonstrate good recoveries (94.9–99.0%) for analyte determination in real water samples. The reproducibility of the method, expressed as RSD% was within 3.1–6.30%. Consequently, this method highlights the adsorbent’s exceptional selectivity and capacity for CZP at trace levels in real-world water samples.

Comparison of proposed method with other methods

A comparison between the developed protocol and other reported methods for the extraction and determination of CZP is presented in Table 3. The comparison factors include the type of extraction and detection system, linearity, LOD, recovery, and RSD. The proposed method demonstrated a wider linear range for the determination of CZP compared to most other reported methods. Additionally, the LOD achieved by this method is lower than those of previously reported techniques. Furthermore, the recoveries and reproducibility of the proposed method for CZP determination are superior to those of other methods, highlighting its effectiveness and reliability.

Conclusion

In this study, a novel urea-modified MOF, MIL-101(Fe)-Urea, was successfully synthesized and proven to be an efficient adsorbent for the SPE of CZP drug in environmental water samples. The modification of MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 with 1,4-phenylene diisocyanate introduced urea functionalities, significantly enhancing the adsorption capability of the MOF and making it a highly selective and sensitive material for CZP extraction. The optimization of key experimental parameters such as pH, adsorbent dosage, eluent type and volume, extraction and desorption times, and sample volume, enabling the development of an efficient analytical method. The proposed method exhibited exceptional analytical performance, including a low limit of detection (LOD, 0.03 µg L−1), excellent linearity (20–1500 µg L−1, R2 = 0.997), high selectivity, and good reproducibility (RSD < 3.1%). Recovery studies validated the technique validation and reliability, complying with ICH guidelines, and confirmed its suitability for practical environmental analysis. The findings highlight the importance of advanced environmental monitoring techniques to protect human health and ecosystems from pharmaceutical contaminants while demonstrating the potential of MOFs in environmental analytical chemistry. In addition to its high analytical performance, the developed method was evaluated based on green analytical chemistry principles. The solid-phase extraction approach notably decreased solvent consumption, as only 1.0 mL of methanol was needed for desorption. The consumption of MIL-101(Fe)-Urea adsorbent was very low and it was reusable, keeping its efficiency even after multiple extraction cycles, thus reducing material waste. The extraction time of this method was short and takes ten minutes. It revealed simple operation and reduces energy consumption. These features make this method more sustainable and make it a suitable option for monitoring pharmaceutical contaminants in water samples that have high environmentally friendly features.

Data availability

“The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.”

References

López-García, E. et al. Drugs of abuse and their metabolites in river sediments: analysis, occurrence in four Spanish river basins and environmental risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 401, 123312 (2021).

Ramírez-Morales, D. et al. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals, hazard assessment and ecotoxicological evaluation of wastewater treatment plants in Costa Rica. Sci. Total Environ. 746, 141200 (2020).

Hu, P. et al. Occurrence, distribution and risk assessment of abused drugs and their metabolites in a typical urban river in North China. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 13, 1–11 (2019).

Pivetta, R. C., Rodrigues-Silva, C., Ribeiro, A. R. & Rath, S. Tracking the occurrence of psychotropic pharmaceuticals in Brazilian wastewater treatment plants and surface water, with assessment of environmental risks. Sci. Total Environ. 727, 138661 (2020).

Aryal, N. et al. Fate of environmental pollutants: A review. Water Environ. Res. 92, 1587–1594 (2020).

Al-Kuraishy, H. M., Al-Gareeb, A. I., Saad, H. M. & Batiha, G. E.-S. Benzodiazepines in alzheimer’s disease: beneficial or detrimental effects. Inflammopharmacology 31, 221–230 (2023).

Al-Otaibi, F. Safety and efficacy of clonazepam in the treatment of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: A meta-analysis. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 14, 126–131 (2022).

Dokkedal-Silva, V., Berro, L. F., Galduróz, J. C. F., Tufik, S. & Andersen, M. L. Clonazepam: indications, side effects, and potential for nonmedical use. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 27, 279–289 (2019).

Ozone, M., Shimazaki, H., Ichikawa, H. & Shigeta, M. Efficacy of Yokukansan compared with clonazepam for rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder: A preliminary retrospective study. Psychogeriatrics 20, 681–690 (2020).

de Araujo, F. G., Bauerfeldt, G. F., Marques, M. & Martins, E. M. Development and validation of an analytical method for the detection and quantification of bromazepam, clonazepam and diazepam by UPLC-MS/MS in surface water. Bull. Environ Contam. Toxicol. 103, 362–366 (2019).

Nason, S., Lin, E., Eitzer, B. D., Koelmel, J. P. & Peccia, J. Traffic, drugs, mental health, and disinfectants: changes in sewage sludge chemical signatures during a COVID-19 community lockdown. (2021).

Soylak, M. & Jagirani, M. S. Vol. 27, 450–452 (Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, 2021).

Pacheco, C. R., Hilares, R. T., Andrade, G. C., Mogrovejo-Valdivia, A. & Tanaka, D. A. P. Emerging contaminants, SARS-COV-2 and wastewater treatment plants, new challenges to confront: a short review. Bioresource Technol. Rep. 15, 100731 (2021).

Cunha, D. L., de Araujo, F. G. & Marques, M. Psychoactive drugs: occurrence in aquatic environment, analytical methods, and ecotoxicity—a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 24076–24091 (2017).

Khoshroo, A., Hosseinzadeh, L., Sobhani-Nasab, A., Rahimi-Nasrabadi, M. & Ahmadi, F. Silver nanofibers/ionic liquid nanocomposite based electrochemical sensor for detection of clonazepam via electrochemically amplified detection. Microchem. J. 145, 1185–1190 (2019).

Guina, J. & Merrill, B. Benzodiazepines I: upping the care on downers: the evidence of risks, benefits and alternatives. J. Clin. Med. 7, 17 (2018).

Raggi, A., Mogavero, M. P., DelRosso, L. M. & Ferri, R. Clonazepam for the management of sleep disorders. Neurol. Sci. 44, 115–128 (2023).

Argaluza, J. et al. Environmental pollution with psychiatric drugs. World J. Psychiatry. 11, 791 (2021).

Laouameur, K. et al. Clorazepate removal from aqueous solution by adsorption onto maghnite: experimental and theoretical analysis. J. Mol. Liq. 328, 115430 (2021).

Ghalkhani, M., Majidi, R. & Sohouli, E. Experimental and theoretical evaluation of the clonazepam adsorption onto carbon nanotubes. Chem. Phys. 558, 111505 (2022).

Jagirani, M. S. & Soylak, M. A review: recent advances in solid phase Microextraction of toxic pollutants using nanotechnology scenario. Microchem. J. 159, 105436 (2020).

Sharifi-Rad, M., Kaykhaii, M., Khajeh, M. & Oveisi, A. Synthesis, characterization and application of a zirconium-based MOF-808 functionalized with Isonicotinic acid for fast and efficient solid phase extraction of uranium (VI) from wastewater prior to its spectrophotometric determination. BMC Chem. 16, 27 (2022).

Nazri, S. et al. Thiol-functionalized PCN-222 MOF for fast and selective extraction of gold ions from aqueous media. Sep. Purif. Technol. 259, 118197 (2021).

Soylak, M., Ozalp, O. & Uzcan, F. Magnetic nanomaterials for the removal, separation and preconcentration of organic and inorganic pollutants at trace levels and their practical applications: A review. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 29, e00109 (2021).

Lei, H. J. et al. Occurrence, fate and mass loading of benzodiazepines and their transformation products in eleven wastewater treatment plants in Guangdong province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 755, 142648 (2021).

Liang, J. et al. Simultaneous occurrence of psychotropic pharmaceuticals in surface water of the megacity Shanghai and implication for their ecotoxicological risks. ACS ES&T Water. 1, 825–836 (2021).

Davey, C. J., Kraak, M. H., Praetorius, A., Ter Laak, T. L. & van Wezel, A. P. Occurrence, hazard, and risk of psychopharmaceuticals and illicit drugs in European surface waters. Water Res. 222, 118878 (2022).

Hasani, S., Arvand, M. & Habibi, M. F. Efficient on–off photoelectrochemical sensing platform with layer-by-layer assembly of titanium dioxide nanotube arrays and silver@ zinc sulfide nanoparticles for unbiased and accurate monitoring of clonazepam. Microchem. J. 185, 108253 (2023).

Lotfi, S. & Veisi, H. Electrochemical determination of clonazepam drug based on glassy carbon electrode modified with Fe3O4/R-SH/Pd nanocomposite. Mater. Sci. Engineering: C. 103, 109754 (2019).

Gadge, S. S., Game, M. D. & Salode, V. L. Simultaneous spectrophotometric Estimation of Paroxetine hydrochlorides and clonazepam in bulk and tablet dosage form. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 14, 2497–2501 (2021).

Hashemnia, S., Zarei, H., Mokhtari, Z. & Mokhtari, M. H. An investigation of the effect of PVP-coated silver nanoparticles on the interaction between clonazepam and bovine serum albumin based on molecular dynamics simulations and molecular Docking. J. Mol. Liq. 323, 114915 (2021).

Fang, S. et al. A preliminary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolomics study of rats ingested diazepam or clonazepam. J. Forensic Sci. Med. 6, 117–125 (2020).

Álvarez-Freire, I. et al. Determination of benzodiazepines in pericardial fluid by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 159, 45–52 (2018).

Foudah, A. I. et al. Simultaneous Estimation of Escitalopram and clonazepam in tablet dosage forms using HPLC-DAD method and optimization of chromatographic conditions by box-behnken design. Molecules 27, 4209 (2022).

Buratti, E. et al. Validation of an HPLC–HR-MS method for the determination and quantification of six drugs (morphine, codeine, methadone, alprazolam, clonazepam and quetiapine) in nails. J. Anal. Toxicol. 47, 488–493 (2023).

Uddin, M. N., Samanidou, V. F. & Papadoyannis, I. N. Development and validation of an HPLC method for the determination of six 1, 4-benzodiazepines in pharmaceuticals and human biological fluids. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 31, 1258–1282 (2008).

El Mahjoub, A. & Staub, C. Simultaneous determination of benzodiazepines in whole blood or serum by HPLC/DAD with a semi-micro column. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 23, 447–458 (2000).

Bugey, A. & Staub, C. Rapid analysis of benzodiazepines in whole blood by high-performance liquid chromatography: use of a monolithic column. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 35, 555–562 (2004).

Potka-Wasylka, J. et al. Metal–Organic Frameworks in Green Analytical Chemistry. (2023).

Daliran, S. et al. Defect-enabling zirconium-based metal–organic frameworks for energy and environmental remediation applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. (2024).

Kaykhaii, M., Hashemi, S. H. & Gębicki, J. Applications of metal organic framework adsorbents for pipette-tip micro solid-phase extraction. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 117877 (2024).

Keshavarzi, M., Ghorbani, M., Pakseresht, M., Mohammadi, P. & Shams, A. Development of a dispersive micro solid phase extraction-HPLC method for the simultaneous quantification of antiepileptic drugs in various matrices. Microchem. J. 200, 110455 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Porous Zn (II)-based metal–organic frameworks decorated with carboxylate groups exhibiting high gas adsorption and separation of organic dyes. Cryst. Growth. Des. 18, 7114–7121 (2018).

Zhou, S. et al. Series of highly stable cd (ii)-based MOFs as sensitive and selective sensors for detection of Nitrofuran antibiotic. CrystEngComm 23, 8043–8052 (2021).

Li, Y., Wang, Y., Fan, W. & Sun, D. Flexible metal–organic frameworks for gas storage and separation. Dalton Trans. 51, 4608–4618 (2022).

Daliran, S., Khajeh, M., Oveisi, A. R., García, H. & Luque, R. Porphyrin catecholate iron-based metal–organic framework for efficient visible light-promoted one-pot tandem C–C couplings. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 5315–5322 (2022).

Daliran, S., Khajeh, M., Oveisi, A. R., Albero, J. & García, H. CsCu2I3 nanoparticles incorporated within a mesoporous metal–organic porphyrin framework as a catalyst for one-pot click cycloaddition and oxidation/knoevenagel tandem reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 14, 36515–36526 (2022).

Almáši, M., Zeleňák, V., Palotai, P., Beňová, E. & Zeleňáková, A. Metal-organic framework MIL-101 (Fe)-NH2 functionalized with different long-chain polyamines as drug delivery system. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 93, 115–120 (2018).

Wu, M. X. & Yang, Y. W. Metal–organic framework (MOF)-based drug/cargo delivery and cancer therapy. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606134 (2017).

Hu, T. et al. Novel functionalized metal-organic framework MIL-101 adsorbent for capturing Oxytetracycline. J. Alloys Compd. 727, 114–122 (2017).

Chen, T. & Zhao, D. Post-synthetic modification of metal-organic framework-based membranes for enhanced molecular separations. Coord. Chem. Rev. 491, 215259 (2023).

Kundu, S., Swaroop, A. K. & Selvaraj, J. Metal-organic framework in pharmaceutical drug delivery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 23, 1155–1170 (2023).

Luo, Y. & Su, R. Preparation of NH2-MIL-101 (Fe) metal organic framework and its performance in adsorbing and removing Tetracycline. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 9855 (2024).

Takhvar, A. et al. Metal–Organic frameworks MIL-101 (Fe) and MIL-53 (Al) as efficient adsorbents for dispersive Micro-Solid-Phase extraction of Sorafenib in plasma and wastewater, coupled with HPLC-UV analysis. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 63, bmaf003 (2025).

Rad, L. R., Anbia, M. & Vatanpour, V. MIL-101 (Fe)-and MIL-101 (Fe)-NH2-Loaded thin film nanofiltration membranes for the removal of fluoxetine hydrochloride from pharmaceutical wastewater. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. (2025).

Fu, J., Wang, L., Chen, Y., Yan, D. & Ou, H. Enhancement of aqueous stability of NH 2-MIL-101 (Fe) by hydrophobic grafting post-synthetic modification. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 68560–68571 (2021).

Alhmaunde, A., Masrournia, M. & Javid, A. Facile synthesis of new magnetic sorbent based on MOF-on-MOF for simultaneous extraction and determination of three benzodiazepines in various environmental water samples using dispersive micro solid-phase extraction and HPLC. Microchem. J. 181, 107802 (2022).

Bauer, S. et al. High-throughput assisted rationalization of the formation of metal organic frameworks in the iron (III) aminoterephthalate solvothermal system. Inorg. Chem. 47, 7568–7576 (2008).

Akbarian, M., Sanchooli, E., Oveisi, A. R. & Daliran, S. Choline chloride-coated UiO-66-Urea MOF: A novel multifunctional heterogeneous catalyst for efficient one-pot three-component synthesis of 2-amino-4H-chromenes. J. Mol. Liq. 325, 115228 (2021).

Li, X., Pi, Y., Xia, Q., Li, Z. & Xiao, J. TiO2 encapsulated in Salicylaldehyde-NH2-MIL-101 (Cr) for enhanced visible light-driven photodegradation of MB. Appl. Catal. B. 191, 192–201 (2016).

Wang, J., Huang, X., Gao, H., Li, A. & Wang, C. Construction of CNT@ Cr-MIL-101-NH2 hybrid composite for shape-stabilized phase change materials with enhanced thermal conductivity. Chem. Eng. J. 350, 164–172 (2018).

Guo, H., Niu, B., Wu, X., Zhang, Y. & Ying, S. Effective removal of 2, 4, 6-trinitrophenol over hexagonal metal–organic framework NH2‐MIL‐88B (Fe). Appl. Organomet. Chem. 33, e4580 (2019).

Taha, A. A., Huang, L., Ramakrishna, S. & Liu, Y. MOF [NH2-MIL-101 (Fe)] as a powerful and reusable Fenton-like catalyst. J. Water Process. Eng. 33, 101004 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of Methyl Violet using two new 3D MOFs directed by different carboxylate spacers. CrystEngComm 23, 741–747 (2021).

Tang, J. & Wang, J. Iron-copper bimetallic metal-organic frameworks for efficient Fenton-like degradation of sulfamethoxazole under mild conditions. Chemosphere 241, 125002 (2020).

Kirchon, A., Feng, L., Drake, H. F., Joseph, E. A. & Zhou, H. C. From fundamentals to applications: a toolbox for robust and multifunctional MOF materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 8611–8638 (2018).

Xiong, W. et al. Multi-walled carbon nanotube/amino-functionalized MIL-53 (Fe) composites: remarkable adsorptive removal of antibiotics from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 210, 1061–1069 (2018).

Roberts, J. M. et al. Urea metal–organic frameworks as effective and size-selective hydrogen-bond catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3334–3337 (2012).

Hall, E. A., Redfern, L. R., Wang, M. H. & Scheidt, K. A. Lewis acid activation of a hydrogen bond donor metal–organic framework for catalysis. ACS Catal. 6, 3248–3252 (2016).

Dam, G. K., Let, S., Jaiswal, V. & Ghosh, S. K. Urea-Tethered porous organic polymer (POP) as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for hydrogen bond donating organocatalysis and continuous flow reaction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 3000–3011 (2024).

Zhou, Q. & Liu, G. Urea-functionalized MIL-101 (Cr)@ AC as a new adsorbent to remove Sulfacetamide in wastewater treatment. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 12056–12064 (2020).

Miri, M. G., Khajeh, M., Oveisi, A. R. & Bohlooli, M. Urea-based porous organic polymer/graphene oxide hybrid as a new sorbent for highly efficient extraction of bovine serum albumin prior to its spectrophotometric determination. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 205, 200–206 (2018).

Custelcean, R. & Moyer, B. A. Anion separation with metal–organic frameworks. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 1321–1340 (2007).

Doyle, A. G. & Jacobsen, E. N. Small-molecule H-bond donors in asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Rev. 107, 5713–5743 (2007).

Jayaramulu, K. et al. Hydrophobic metal–organic frameworks. Adv. Mater. 31, 1900820 (2019).

Moghaddam, Z. S., Kaykhaii, M., Khajeh, M. & Oveisi, A. R. Synthesis of UiO-66-OH zirconium metal-organic framework and its application for selective extraction and trace determination of thorium in water samples by spectrophotometry. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 194, 76–82 (2018).

Esmaeili-Shahri, E. Es’ haghi, Z. Superparamagnetic Fe3O4@ SiO2 core–shell composite nanoparticles for the mixed hemimicelle solid‐phase extraction of benzodiazepines from hair and wastewater samples before high‐performance liquid chromatography analysis. J. Sep. Sci. 38, 4095–4104 (2015).

Miri, L. & Jalali, F. Dispersive liquid-liquid micro-extraction as a sample Preparation method for clonazepam analysis in water samples and pharmaceutical Preparations. J. Rep. Pharm. Sci. 2, 103–110 (2013).

Rezaei, F., Yamini, Y., Moradi, M. & Daraei, B. Supramolecular solvent-based Hollow fiber liquid phase Microextraction of benzodiazepines. Anal. Chim. Acta. 804, 135–142 (2013).

Sobczak, Ł., Kołodziej, D. & Goryński, K. Modifying current thin-film Microextraction (TFME) solutions for analyzing prohibited substances: evaluating new coatings using liquid chromatography. J. Pharm. Anal. 12, 470–480 (2022).

Shiri, S., Alizadeh, K. & Abbasi, N. A novel technique for simultaneous determination of drugs using magnetic nanoparticles based dispersive micro-solid-phase extraction in biological fluids and wastewaters. MethodsX 7, 100952 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Research council of the University of Sistan and Baluchestan and the University of Zabol (Grant number: IR-UOZ-GR-9381).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Marzieh Sharifi-Rad: Investigation; Validation; Writing original; Writing review.Asma Khoobi: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.Mostafa Khajeh: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.Massoud Kaykhaii: Supervision; Writing original; Writing review.Ali Reza Oveisi: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharifi-Rad, M., Khoobi, A., Khajeh, M. et al. Highly selective solid phase extraction of clonazepam from water using a urea modified MOF prior to HPLC analysis. Sci Rep 15, 24241 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07127-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07127-x