Abstract

Cubic stratification dramatically enhances thermal and mass transport in quadratic mixed convection, which is advantageous for electronics cooling, biomedical technology, and power plants. Nanofluids are essential to the development of next-generation cooling and environmental management solutions because of their exceptional thermal characteristics. Motivated by such impactful applications in thermal and engineering systems, this work uses the Buongiorno model to examine heat and mass transfer in Maxwell nanofluids over a vertically extended permeable surface under Darcy–Forchheimer porous flow situations. For a more accurate depiction, convective boundary conditions and suction-injection effects are also included in the current analysis. In order to represent complete heat and mass transport behavior, the model also takes into consideration radiative heat flux, viscous heating, chemical reaction, and cross-diffusion effects through the Soret and Dufour mechanisms. Similarity transformations are used to convert the controlling partial differential equations into a system of ordinary differential equations, which are then numerically solved using Mathematica’s NDSolve approach. The influence of important physical parameters on thermal profiles, fluid velocity fields, and concentration distribution is demonstrated in detail through a visual analysis. The skin friction coefficient and local Nusselt and Sherwood numbers are calculated and studied in detail to determine the rates of heat, mass, and surface drag. Important key findings shows that the Velocity filed upsurges with nonlinear thermal and convection parameters, whereas it declines with higher Darcy and Forchheimer resistance effects. Moreover, nanofluid temperature is increased by Dufour and Eckert numbers and decreased by thermal stratification parameter. Finally, Soret and solutal Biot numbers enhance nanoparticle concentration, whereas solutal stratification parameter diminishes it. The results exhibit outstanding consistency with previous research published in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current industrial procedures require extremely effective heat and mass transfer systems, from power conversion and electronics cooling to chemical manufacture and healthcare applications. Conventional working fluids frequently fail to achieve these performance standards. Nanofluids, first presented by Choi1 in 1995, have become a ground-breaking invention to get over these restrictions. Nanofluids greatly improve thermal conductivity, viscosity control, and general transport qualities by distributing nanoparticles into traditional base fluids. Efficiency and compactness of thermal systems could be significantly increased with the help of these cutting-edge fluids. Due to their distinct behavior, a great deal of study has been done to maximize performance in a variety of applications, including medicine delivery, renewable energy systems, and micro-channel heat sinks. In order to simulate their intricate behavior, Buongiorno2 presented a framework for non-homogeneous equilibrium that takes thermophoresis and Brownian motion into account. His investigation showed that temperature gradients and thermophoresis greatly increase the heat transfer coefficient in the boundary layer, underscoring their crucial function in the dynamics of nanofluids. The impacts of suspended nanoparticles in the flow field were incorporated into a computational model for multiphase fluid flow across a stretching sheet by Ahmmed et al.3. In the presence of Brownian diffusion and thermophoresis, Reza-E-Rabbi et al.4 used the finite difference technique to study the chemically reacting MHD movement of Casson fluid on a stretched sheet. The free circulation behavior of a nanofluid based on the Buongiorno model across a diminishing surface was studied analytically by Ratha et al.5. An electrically conducting nanofluid’s free convection flow across an expanding surface was examined by Baag et al.6, taking into account boundary conditions for convective heating and heat generation. Pattnaik et al.7 investigated the free convective flow of a gold-water nanofluid based on the Hamilton-Crosser model in a channel with permeable and moving walls. Yousif et al.8 investigated the behavior of the magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid on the stretched plate surface in terms of heat transport and momentum using computational analysis. There are a number of significant and influential works on this subject in9,10,11 and the references listed therein.

The study of buoyancy-driven flow has traditionally concentrated on linear changes in temperature, concentration, and density due to their major influence on fluid behavior. However, a deeper and more complex layer of convective dynamics is revealed by quadratic fluctuations in these parameters, providing fresh perspectives on nonlinear heat and mass transmission. The existence of both Darcy and non-Darcy porous media significantly shapes surface transport phenomena and improves flow management. Numerous industrial applications, including thermal management systems, combustion, geothermal energy extraction, oil recovery, electronics cooling, and medicinal procedures, find great use for this nonlinear convection architecture. Furthermore, the creation of thermo-resistant polymer sheets emphasizes how crucial it is to take non-linear thermal and solutal gradients into account in practice. Together, these intricate relationships highlight the necessity of sophisticated modeling to more accurately and effectively represent the essence of real-world engineering systems. The consequences of quadratic convection have been further investigated in recent research by Balamurugan and Kumar12,13, Khan et al.14,15,16 and Patil et al.17,18,19 which have provided important insights into its significance in complicated fluid flow systems.

The rate type fluid Maxwell non-Newtonian fluid flow model plays a crucial part in numerous engineering applications because it aids in elucidating how heat transfers over ingredients that have together liquid-like (viscous) and solid-like (elastic) properties. This model is highly useful for improving processes using materials like lubricants, polymeric fluids, and nanofluids where temperature management is crucial for both efficiency as well as security. For example, the medical industry uses the Maxwell model to improve knowledge of biological fluid performance and develop advanced cooling systems for biomedical devices. Because it can explain how these fluids respond to heat and mechanical forces, it can be used to improve energy systems, chemical processes, and many engineering solutions. Investigators such as Hayat et al.20 have beforehand inspected the influences of Hall currents on peristalsis motion in Maxwell fluid flow through porous materials. Far ahead, Khan et al.21 discussed the viscoelastic Maxwell model to take in further information about the dynamics of viscoelastic fluids. Noteworthy aids are also made by Nadeem et al.22, who considered the impacts of chemical processes on viscoelastic fluid flow. In a detached effort, Hayat et al.23 discovered how thermo-phoretic diffusion and Brownian motion control the behavior of magnetized Maxwell fluid flow on a stretching surface. Khan et al.24 observed thermal and solutal stratified flow behavior on the viscoelastic Maxwell fluid motion, precisely how flow is obstructed by variations in viscosity. This notion is protracted by Ahmad et al.25, who used the terminology of thermal as well as solutal stratified flow model to analyze heat and mass transmission in these fluids. A hybrid computational approach was developed by Pattnaik et al.26 to examine the impact of chemical reactions and heat radiation on the flow behavior of a viscoelastic nanofluid. Zhong et al.27 announced the idea of the most popular phenomenon thermo-capillary convection in viscoelastic Maxwell fluid flow, which amended the knowledge of intricate thermal phenomena. We now have a far better knowledge of fluid dynamics during heating processes, particularly inflows driven by surface tension, thanks to this groundbreaking study. In recent times, the properties of Hall currents and magnetic fields on the flowing of 2nd-grade radiative nanoliquids across a Riga surface with convective heat transference are considered by Gangadhar et al.28. Recently, Gangadhar et al.29 investigated the dynamics of auto-catalytic processes in Burgers’ fluid flow, specifically focusing on the interaction underlying magnetization and convective heat transport.

Solar radiation is essential to the movement of energy in high-temperature manufacturing processes, particularly in furnaces, combustion chambers, and solar energy collectors. The dynamics of heat transfer become much more complex when combined with viscous heating, which takes into consideration the internal conversion of kinetic energy into thermal energy as a result of fluid friction, especially in high-viscosity or high-speed flows. Convective heating conditions, in which convective heat transfer coefficients control heat exchange between the fluid’s surface and surrounding fluid, are used to make modeling scenarios like metal processing, polymer extrusion, and electronic equipment cooling more realistic. In sophisticated manufacturing, aircraft, nuclear reactors, and thermal management technologies, these combined effects are essential for improving thermal performance, maximizing design parameters, and guaranteeing energy efficiency. These phenomena make predictive models more reliable and useful for engineering systems in the actual world. Panda et al.30 used regression analysis for optimization and an artificial neural network to estimate how the concentration of nanoparticles affects dissipative heat transfer in a water-based hybrid nanofluid under slip conditions. Using a heat source and convective heating boundary conditions, Baag et al.6 examined the free convection flow of a conducting nanofluid past an expanding surface. With a focus on stability analysis for dual solutions, Tinker et al.31 examined the simulation of time-dependent radiative heat transfer in a hybrid nanofluid flow across a stretching/shrinking sheet. In order to investigate heat transfer in radiative Carreau tri-hybrid nanofluid flow with entropy production, Pattnaik et al.32 used response surface methods to construct a significant statistical model that has applications in solar-powered aircraft systems. Using the Gauss-Lobatto IIIA numerical scheme for precise analysis, Shamshuddin et al.33 investigated the various impacts of dissipative heat transfer in radiative micropolar hybrid nanofluid flow across a wedged surface. In order to demonstrate the effect of thermal radiation on system performance, Mishra et al.34 performed a statistical analysis on the improved heat transfer behavior of radiative hybrid nanofluid flow over a spinning vertical cone.

The term “stratification” describes the layering of various materials or fluids brought on by changes in composition, temperature, or density. Because it affects mass movement, heat transmission, and flow patterns in fluids, this phenomenon is important in both natural and artificial systems. Stratification poses a risk to industrial systems like heat exchangers, where temperature gradients can improve energy efficiency. Although stratification has various uses, its most significant application is in environmental management, where it aids in the regulation of the marine environment in ponds, streams, wetlands, and oceans. It is also important in solar ponds and power plant condensers35. Since exact control over fluid layers greatly improves treatment outcomes, a solid knowledge of stratification is essential in the medical industry for building drug delivery systems and optimizing thermal therapy. The dynamics of nanofluid flow close to stagnation points are investigated by Farooq et al.36, taking into account the effects of melting instances as well as thermal and solutal stratification. Their research emphasizes how complicated boundary interactions interact with heat and mass transmission mechanisms. Squeezing slip flow dynamics over lower deformable surfaces are explored by Ahmad et al.37, who emphasized the significance of dual stratified flowing. In their study of Maxwell nanofluid motion across inclined flexible surfaces, Ali et al.38 addressed heat source and sink effects in addition to dual stratification. Nonlinear stratified Eyring-Powell fluid flows are studied by Jabeen et al.39, who combined mixed convection phenomena with sophisticated diffusion processes. Falkner-Skan-type flow in Jeffrey fluids with nonlinear stratification is investigated by Malik et al.40. Their research examined mixed convection effects and emphasized the influence of stagnation points on flow dynamics. The heat transfer process in Falkner-Skan flow of a buoyancy-driven, dissipative hybrid nanofluid over a vertical permeable wedge was examined by Panda et al.41, taking into account the impacts of varying wall temperature. The behavior of convective motion-driven nonlinear stratified flow on stretchy inclined surfaces is assessed by Khan et al.42. Using artificial neural networks for data analysis, Shafiq et al.43 explored the influences of convective heating and nonlinear stratification in non-Darcian squeezing flows. dual stratified phenomenon in the flowing of magnetized non-Newtonian fluids exposed to deformation by inclined stretchable surfaces with reactive qualities is examined by Khalil et al.44. Refs45,46. emphasize the broad exploration of stratification in fluid flow and heat transmission in a number of recent works. These studies offer insightful information about the intricate impacts of temperature and solutal stratification, which emphasizes the necessity for more studies in this area.

In numerous cutting-edge industrial processes, precise regulation of heat and mass transfer is necessary to ensure material durability and optimal performance. Motivated by this pressing commercial requirement, thus the current work is to scrutinize Maxwell nanofluid flow in a Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium over a vertically stretchy permeable surface with quadratic mixed convection effects. One important novelty is the incorporation of cubic stratification with cross diffusion and convective heating conditions, which provides a more accurate and realistic representation of temperature and concentration gradients than traditional linear approximations, thus capturing intricate thermal and solutal fluctuations seen in real-world systems. To provide a comprehensive framework for examining transport phenomena, this work combines these effects in a unique way with Brownian diffusion, thermophoretic force, viscous heating, radiative thermal transfer, heat generation/absorption, chemical reactions, and suction/injection dynamics. The resulting model deepens our understanding of non-Newtonian Maxwell nanofluids in porous media and provides essential information for improving industrial processes like glassmaking, polymer extrusion, and controlled cooling of metallic components, where minimizing thermal stresses and avoiding material defects are critical. The study solves the modified nonlinear ODEs using the ND-Solve numerical methodology and uses in-depth graphical analysis to methodically investigate how important parameters affect the velocity, temperature, and concentration fields. This comprehensive method tackles real-world issues in material processing and thermal management in addition to enhancing theoretical fluid dynamics. The current research work is driven by pivotal questions:

-

What is the impact of cubic stratification on Maxwell-Buongiorno nanofluid thermal performance and nonlinear mixed convection?

-

What are the effects of Brownian motion, thermophoresis, and Darcy-Forchheimer drag on the flow, heat, and mass transfer characteristics?

-

What effects do heat generation/absorption, thermal radiation, and viscous dissipation have on the temperature distribution?

-

How do the Dufour and Soret effects alter thermal transport and concentration in chemically reactive flows?

-

How do suction/injection and convective boundary conditions impact the boundary layer behavior and transfer rates?

Problem description

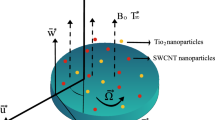

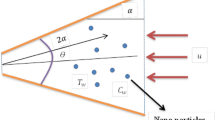

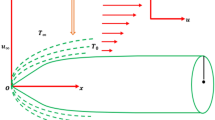

In this paper, the radiative, two-dimensional nonlinear mixed convective flow of a Maxwell fluid across a vertically extended permeable surface is investigated, with a focus on the role of injection and suction as mass transfer mechanisms. To better depict the behavior of heat transport, convective boundary conditions and cubic stratification are incorporated. It must be noted that mixed convection is affected by strong thermal and concentration gradients. Density variations necessitate the use of second-order terms when these gradients are considerable, providing a more thorough and precise understanding of the flow dynamics. The impacts of an external heat source, a non-Darcy porous media, viscous dissipation effects, and cross-diffusion phenomena are also included in this study. It is assumed that the flow takes place in a Cartesian coordinate system, as shown in Fig. 1, where the y-axis is perpendicular to the vertically stretched surface and the x-axis runs along it. The surface temperature and concentration are denoted by \(\:{T}_{s}\) and \(\:{C}_{f}\), respectively, while the ambient conditions are characterized by \(\:{T}_{\infty\:}\) and \(\:{C}_{\infty\:}\). The sheet is stretched with a velocity \(\:{u}_{w}\). To capture the intricate behavior of the nanofluid under these settings, Buongiorno’s model is employed, emphasizing the critical role of nanoparticle-induced diffusion mechanisms in nanoliquid dynamics.

The governing equations for the Maxwell fluid flow are formulated under standard boundary layer approximations47,48:

The associated boundary conditions are49:

Where

Here the symbol \(\:u\) and \(\:v\) are the velocity components in \(\:x\) and \(\:y\) directions respectively, \(\:\nu\:\) denotes kinematic viscosity, the symbol \(\:\lambda\:\) represent Deborah number, \(\:g\) symbolizes accelaration due to gravity, \(\:{\beta\:}_{T}\) denotes thermal expansion coefficient,\(\:T\) is temperature of fluid, \(\:{\beta\:}_{C}\) represents solutal expansion coefficient, \(\:C\) symbolizes concentration, \(\:{k}^{*}\) denotes permeability of porous medium, \(\:{C}_{b}\) Drag coefficient per unit length, \(\:\tau\:\) ratio of heat capacity of nanoparticles and base fluid, \(\:{T}_{0}\) and \(\:{C}_{0}\) represents the reference temperature and concentration respectively,\(\:{D}_{B}\) represents the Brownian diffusion coefficeint,\(\:{D}_{T}\) the thermophoreetic diffusion coefficient, \(\:k\) is the thermal conductivity \(\:D\) symbolizes diffusion coefficient, \(\:{K}_{T}\) the thermal diffusion ratio, \(\:{c}_{s}\) means Concentration susceptibility, \(\:cp\) denotes Specific heat capacity at constant pressure, \(\:{Q}_{2}\) denotes the coefficient of heat generation or absorption, \(\:\rho\:\) is the fluid density, \(\:{\sigma\:}^{*}\) denotes Stefan Boltzmann constant, \(\:{K}^{*}\) symbolizes Mean absorption coefficient, \(\:{T}_{m}\) denotes mean temperature, \(\:{K}_{r}\) denotes the reaction rate, however for the cases \(\:{k}_{r}<0\) and \(\:{k}_{r}>0\) represents generative and distructive reactions respectively, and \(\:{h}_{f}\) and \(\:{h}_{c}\) represents convective heat and mass transfer at the surface respectively, \(\:a,{D}_{1},{D}_{2},{E}_{1},{E}_{2}\) are depicts dimensional contants.

To modify Eqs. (1)–(5), the transformation50:

is employed, hence one obtains:

Here \(\:\beta\:\) denotes time relaxation ratio, \(\:Da\) represents Darcy number, \(\:{F}_{r}\) is Forchheimer parameter, \(\:{C}_{b}^{*}\) means Drag coefficient per unit length, \(\:\lambda\:\) is Mixed convection parameter, \(\:{\lambda\:}_{T}\) denotes Nonlinear thermal convection parameter, \(\:{\lambda\:}_{C}\) represents Nonlinear solutal convection parameter, \(\:{Gr}_{t}\) Convection term for temperature, \(\:{Gr}_{C}\) Nonlinear solutal convection term, \(\:{Re}_{x}\) is Local Reynolds number, \(\:Pr\) for Prandtl number, \(\:{R}_{d}\) characterizes thermal radiation parameter, \(\:{H}_{g}\) the Heat generation parameter, \(\:{D}_{e}\) represents Dufour number, \(\:{S}_{e}\) means Soret parameter, \(\:\gamma\:\) is Chemical reaction parameter, \(\:{S}_{1}\) and \(\:{S}_{2}\) represents thermal and Solutal stratification parameter respectively, \(\:Le\) the Lewis parameter, the symbol \(\:Ec\) denotes Eckert number, \(\:{N}_{b}\) represents Brownian motion parameter, \(\:{N}_{t}\) Thermophoresis parameter, \(\:{B}_{t}\) characterizes Thermal Biot number, \(\:{B}_{s}\) symbolizes Solutal Biot number. Mathematically,

The wall shear stress is defined by

The surface heat transfer is expressed as

The surface mass transfer is expressed as,

In this work, the effective thermophysical properties of nanoparticles are not taken into account when analyzing the concentration equation for nanofluids. Similarly, when the governing boundary layer equations are being formulated, these features are not included. Additionally, the formulations for the local Sherwood and Nusselt numbers, which measure mass and heat transport rates, respectively, do not account for the influence of nanoparticles.

Description of the computational approach

To solve the coupled nonlinear ordinary differential equation system Eqs. (8)-(12), Mathematica’s ND Solve function is employed. This method discretely evaluates the dependent variables \(\:{F}_{1},{F}_{2},{F}_{3}\dots\:{F}_{n}\) over the similarity domain \(\:\eta\:\in\:\left[{\eta\:}_{min},{\eta\:}_{max}\right]\) using the form:

Due to the nonlinearity and strong coupling between variables, analytical solutions are impractical. Hence, ND Solve, based on an adaptive 4th-order Runge-Kutta method, provides a reliable and efficient numerical solution. This method effectively handles boundary value problems and is well-suited for complex fluid flow simulations.

Verification of the mathematical outcomes

To confirm the correctness of our outcomes, a comparative examination is presented in Table 1, display a robust agreement with previous studies51,52. The vital benefits of the technique applied here are:

-

It delivers highly accurate results.

-

It requires less CPU time, improving efficiency.

-

It is more robust and reliable for well-posed, real-world problems.

Results and discussion

In this section, numerical solutions for Eqs. (8)–(11) are obtained using the numerical ND-Solve (Built-in) technique. The resulting temperature, velocity, and concentration fields are shown graphically to show how different influencing factors affect the results. Furthermore, Tables 3 and 4 present numerical estimates for surface heat flow, surface shear stress, and surface mass flux, respectively, providing a thorough understanding of these crucial surface characteristics.

By investigating the outcomes of the analysis, one may determine how different physical characteristics affect the velocity field are shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. Figure 2 shows that the nanofluid velocity drops as the Deborah number \(\:\left(\beta\:\right)\) rises. Physically, a fluid that has a higher Deborah number resists deformation and slows down due to stronger elastic effects. This illustrates the memory effect of viscoelastic fluids, in which present flow is influenced by previous stresses. Such behavior is important for industrial applications, such as polymer manufacturing, where regulating flow rates is essential to the quality of the final product. It is easier to augment processes involving non-Newtonian nanofluids in Darcy porous and elastic media when this relationship is understood. The fluid velocity increases in tandem with the nonlinear convection parameter \(\:\left({\lambda\:}_{t}\right)\), as illustrated in Fig. 3. This happens because the upward flow motion is enhanced by higher buoyant forces from nonlinear thermal gradients. The nonlinear term accelerates fluid flow close to the surface by intensifying heat driving. In energy devices and cooling systems, where improved convection boosts thermal performance, this exceptional behavior is essential. Additionally, it facilitates the development of effective heat exchangers in nonlinear thermal conditions by employing nanofluids. Figure 4 shows that nanofluid velocity increases as the nonlinear solutal convection parameter \(\:\left({\lambda\:}_{c}\right)\) increases. This is because nonlinear concentration gradients produce stronger flow motion through increased solutal buoyancy forces. By increasing mass transfer, the nonlinear solutal effect speeds up fluid flow. This feature is important in bioengineering and chemical processing, where accurate control over solute transport is essential. It facilitates the effective design of systems that use mixing and separation techniques with nanofluids. As can be seen in Fig. 5, the fluid velocity is much increased when the thermal Grashof number rises. The reason for this is that a higher Grashof number indicates stronger buoyant forces caused by temperature variations, which outweigh viscous resistance and quicken the flow. Vigorous convection is encouraged by the increased thermal buoyancy, particularly in areas with sharp thermal gradients. In cooling technologies, solar collectors, and thermal management systems, where natural convection is essential, this phenomena is vital. By comprehending this impact, energy-efficient designs utilizing nanofluids in heat-sensitive manufacturing procedures can be optimized. Figure 6 shows that the nanofluid velocity increases in proportion to the solutal Grashof number. This is due to the fact that a larger solutal Grashof number indicates stronger buoyant forces produced by concentration, which improve flow dynamics. By lessening the impact of viscoelastic drag, these forces encourage quicker fluid motion. In environments where solute-induced convection predominates, such behavior is especially crucial in chemical reactors, desalination systems, and pharmaceutical transportation. The construction of sophisticated nanofluid systems with enhanced transmission of mass efficiency in solutal-gradient situations is supported by this realization. As can be seen in Fig. 7, fluid velocity decreases as the Darcy parameter rises. In a physical sense, a higher Darcy number means more flow resistance because the porous medium’s decreased permeability inhibits fluid motion. There is a slower flow as a result of this dampening effect overriding buoyant forces. Such behavior is essential for regulating flow via porous structures in thermal insulation, groundwater hydrology, and filtration systems. This knowledge facilitates the design of porous materials for applications involving nanofluids that require optimal flow control. Figure 8 illustrates how fluid velocity decreases when the Darcy–Forchheimer parameter rises. This component adds nonlinear drag to the flow and takes into consideration inertial resistance in porous media, which becomes substantial at higher velocities. Beyond the linear Darcy resistance, fluid motion is further suppressed by the increasing inertial effects. This phenomena is important because inertial losses impact the efficiency of industrialized packed-bed reactors, high-speed filtration, and oil recovery. Comprehending this facilitates the development of effective porous systems that manage particles with irregular drag forces. Figure 9 shows that nanofluid velocity decreases as the suction–injection parameter increases. By physically removing fluid, wall suction reduces flow thickness and suppresses velocity close to the surface, stabilizing the boundary layer. This control system improves flow regularity while decreasing buoyancy-induced motion. Boundary layer control, electronic component cooling, and aeronautical applications all heavily rely on this characteristic. For improved thermal control and process efficiency, accurate control of nanofluid flow is made possible by properly adjusting the suction parameters.

The Deborah number \(\:\beta\:\), radiation parameter \(\:{R}_{d}\), Dufour effect \(\:{D}_{e}\), Prandtl number \(\:Pr\), thermal stratification parameter \(\:{S}_{1}\), Brownian movement variable \(\:{N}_{b}\), Eckert parameter \(\:Ec\)thermophoretic variable \(\:{N}_{t}\), Biot number \(\:{B}_{t}\), and heat generation \(\:{H}_{g}\) are some of the parameters that are depicted in Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19. Together, all these factors influence the model’s dynamic behavior. Figure 10 illustrates that the fluid temperature rises in tandem with the Deborah number. This happens because fluids with higher Deborah numbers exhibit larger elastic effects, which lower the efficiency of convective heat transport and lead to the accumulation of heat. Elevated temperature profiles result from the fluid’s memory effect, which postpones thermal diffusion. Monitoring heat transfer under viscoelastic conditions is crucial in sophisticated cooling systems and polymeric fluid processing, where this understanding is crucial. Comprehending this correlation facilitates the enhancement of temperature control tactics for viscoelastic nanofluids. In addition, the nanofluid temperature rises as the thermal radiation parameter increases, as seen in Fig. 11. The system gains energy via enhanced thermal radiation, which intensifies radiative heat flow heat transmission. By raising the thermal boundary layer temperature, this extra heat source lessens the cooling effect of convection. Thermal insulation design, solar energy systems, and high-temperature industrial operations all depend on this characteristic. In applications using nanofluid-based thermal management, an understanding of this effect aids in optimizing radiative heat transfer control. Figure 12 illustrates how the fluid temperature drops as the Prandtl number rises. A thinner thermal boundary layer results from lower thermal diffusivity in relation to momentum diffusivity, which is indicated by a greater Prandtl number. This lowers the fluid temperature by improving dissipation of heat away from the surface. In cooling technologies and heat exchanger design, where effective thermal management is crucial, this effect is crucial. As the Dufour number rises, the fluid temperature rises as well, as shown in Fig. 13. The Dufour effect, which is a representation of heat flow brought on by concentration gradients, increases the system’s thermal energy and raises the temperature close to the surface. The fluid’s overall heat transfer is improved by this cross-diffusion process. Such behavior is crucial for applications involving the heat transfer of nanofluids, chemical reactors, and thermo-diffusion processes. The fluid temperature rises as the Brownian motion parameter increases, as seen in Fig. 14. The random movement of nanoparticles is intensified by enhanced Brownian motion, which increases the dispersion of thermal energy in the nanofluid. As a result, temperature profiles rise and thermal boundary layers get thicker. These effects are essential for microelectronic thermal management and cooling systems based on nanofluids. The fluid temperature rises as the thermophoresis parameter increases, as shown in Fig. 15. Nanoparticles are driven from hotter to cooler locations by thermophoresis, which causes particle buildup that modifies thermal conductivity and heat transmission rates. The fluid temperature rises as a result of this mechanism’s increased heat retention close to the heated surface. This is important for chemical reactors, colloidal processing, and controlling the temperature of nanofluids. Figure 16 illustrates how nanofluid temperature decreases as the thermal stratification parameter rises. By forming stable temperature layers that prevent vertical heat flow, thermal stratification lowers fluid thermal mixing. Lower temperatures close to the heated surface and a smaller thermal boundary layer are the results of this stabilization. In energy storage systems, building insulation, and environmental engineering, this kind of behavior is crucial. The fluid temperature rises noticeably as the Eckert number rises, as shown in Fig. 17. This is due to the fact that the Eckert number measures how kinetic energy is transformed into internal energy by viscous dissipation, which heats the fluid directly. The temperature field rises as more mechanical energy is converted to thermal energy by increasing viscous forces. In lubrication systems, high-speed flows, and microfluidic instruments where frictional heating affects performance, this phenomena is particularly important. The nanofluid temperature rises noticeably as the heat generation parameter increases, as seen in Fig. 18. By supplying thermal energy directly to the fluid medium, internal heat generation serves as a volumetric energy source. Temperature profiles rise as a result of the thermal boundary layer being strengthened by this more heat. In nuclear reactors, electronic cooling, and chemical processes, where controlling internal heat sources is crucial, these effects are crucial. Figure 19 illustrates how a higher thermal Biot number causes the nanofluid temperature to rise. Stronger convective heat transfer at the boundary, which lowers thermal resistance between the fluid and its surroundings, is indicated by a higher Biot number. This increases the fluid’s capacity to retain heat, raising the temperature close to the surface. Designing heat exchangers, thermal insulation, and material processing all depend on this behavior.

Furthermore, the concentration distribution of nanofluids across various physical parameters is depicted in Figs. 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and 26. The solute concentration falls as the Lewis number rises, as shown in Fig. 20. Mass diffusion is slower than heat transmission when thermal diffusivity predominates, as indicated by a greater Lewis number. As a result, there is less solute accumulation close to the surface and a thinner concentration boundary layer. Applications such as transport of mass control, chemical separation, and nanofluid mixing depend on this characteristic. Figure 21 illustrates how the solute concentration rises as the Soret parameter increases. Solute migration toward hotter locations is enhanced by the Soret effect, which produces mass flux driven by temperature gradients. Local solute buildup is increased by this thermally induced diffusion, which deepens the concentration boundary layer. Chemical engineering, thermo-diffusion processes, and nanofluid transport phenomena all benefit from this kind of behavior. The solute concentration decreases as the thermophoresis and Brownian motion parameters are increased, as seen in Figs. 22 and 23. Stronger nanoparticle agitation is encouraged by enhanced Brownian motion, which enhances mass diffusion and lessens the accumulation of local concentrations. Stronger thermophoresis also thins the concentration boundary layer by pushing particles away from hotter areas. Uniform mixing and effective dispersion of nanoparticles are made possible by these combined actions. In chemical reactors, drug delivery systems, and nanofluid stability, where regulated concentration gradients maximize efficiency, this characteristic is essential. As the stratification parameter is increased, the solute concentration decreases, as seen in Fig. 24. By stabilizing the fluid layers, stratification reduces solute collection close to the surface and inhibits vertical mass transport. Thinner concentration boundary layers are the outcome of this layered stability, which lessens mixing intensity. Oceanography, chemical separation processes, and environmental flows all depend on these effects. As seen in Fig. 25, the concentration of the solute decreases as the chemical reaction parameter increases. Solute species are consumed by enhanced chemical processes, which lowers their local concentration. Concentration profiles close to reactive surfaces are determined by the dynamic interaction between mass transport and reaction kinetics. These kinds of insights are essential for biological processes, waste treatment, and catalytic reactors. Optimizing solute removal and system efficiency is made possible by controlling reaction rates. The solute concentration rises as the solutal Biot parameter increases, as shown in Fig. 26. A greater Biot number indicates increased resistance to mass transfer at the border, which leads to solute buildup in the fluid. By thickening the concentration boundary layer, this effect improves solute retention close to the surface. Applications involving nanofluids, material processing, and mass transfer-limited systems all benefit from this phenomenon. Controlling surface mass exchange processes precisely is made possible by an understanding of Biot effects.

Tables 2, 3 and 4 show how different physical parameters affect the local Sherwood number \(\:{\varphi\:}^{{\prime\:}}\left(0\right)\), the skin friction parameter \(\:{f}^{{\prime\:}{\prime\:}}\left(0\right)\), and the local Nusselt number \(\:{\theta\:}^{{\prime\:}}\left(0\right)\).The study compares nanofluids using two different numerical techniques: a new iterative method and the integrated ND-Solve approach. The surface frictional force factor, Sherwood, and Nusselt numbers are assessed in this comparison. To estimate important parameters of surface frictional force, Sherwood, and Nusselt numbers in a nanofluid system that is still mostly unexplored, the efficacy and accuracy of the ND-Solve and iterative approaches will be evaluated and compared. To illustrate the benefits and drawbacks of each strategy, the study will look at how well each method can represent these parameters. This evaluation clarifies the precision and potential applications of these numerical techniques in the investigation of nanofluid dynamics.

A contrast of drag force coefficients for nanofluid flow with dissimilar parameter values is shown in Table 2. The outcomes confirm that as the Forchheimer parameter \(\:{F}_{r}\), nonlinear thermal mixed convection \(\:{\lambda\:}_{t}\) and nonlinear solutal convection variable \(\:{\lambda\:}_{s}\) rise, the drag force tends to rise. On the contrary, as the suction/injection variable \(\:S\) and the Deborah number \(\:\beta\:\) surge, the drag force coefficient displays a decreasing outline. This learning clasps true for both studied approaches, highlighting the complex impact of these parameters on the behavior of nanofluids.

Furthermore, a comparison of the heat transfer rate under diverse parameter values is given in Table 3. The findings determine that as the heat generating (absorbing) variable \(\:{H}_{g}\), the Brownian diffusion parameter \(\:{N}_{b}\), thermophoretic diffusion parameter \(\:{N}_{t}\), solar radiation parameter \(\:{R}_{d}\) and Biot number \(\:{B}_{s}\) raise, and so does the heat transference rates. On the other hand, the heat transference rates reduction when the Prandtl number \(\:Pr\), Eckert number \(\:Ec\) and thermal stratification parameter \(\:{S}_{1}\) increase. This outline is relentless for both approaches, highlighting how sensitive thermal behavior in nanofluids is to these features. Table 4 displays a comparison of the Sherwood number for nanofluids. The outcomes show that the Surface mass transfer rate upsurges with heightening levels of the solutal Biot number \(\:{B}_{s}\) and the thermophoretic diffusion parameter \(\:{N}_{t}\). On the contrary, in mutual approaches, the Sherwood number falls as the Brownian diffusion parameter \(\:{N}_{b}\), Lewis number \(\:Le\), chemical reaction parameter \(\:\gamma\:\) and solutal stratification parameter \(\:{S}_{2}\)increase. This reveals how complicatedly numerous parameters cooperate to affect the performance of mass transfer rate in nanofluids.

In proportion to the study’s outcomes, the new iterative approach is not as accurate, consistent, or precise as the integrated ND Solve method. This outcome shows how well the ND-Solve approach simulates the behavior of nanofluids and predicts crucial parameters such as the surface frictional force factor, Sherwood, and Nusselt numbers. Given its improved performance, the ND-Solve approach might prove to be a more reliable choice for future studies in this area. Consequently, researchers may consider prioritizing this approach when investigating complex fluid dynamics, including nanofluids.

Concluding remarks

In this work, the nonlinear mixed convective flow of a two-dimensional Maxwell nanofluid through a vertically stretchable surface is studied. Special attention is paid to the combined effects of solar thermal radiation, cross-diffusion mechanisms, and suction/injection-driven mass transfer.

Moreover, under convective boundary conditions, the effects of thermophoresis and Brownian motion on nanoparticles are taken into account. More significantly, to improve heat transfer investigation, cubic stratification is also incorporated. The ND Solve (built in function) approach in Mathematica is then used to numerically solve the governing equations.

Numerous important findings into the characteristics of cubic stratified nonlinear mixed convective flow with cross diffusion phenomenon in nanofluid systems are revealed by the current investigation. The following is a summary of the key findings: Due to augmented resistance and memory effects in the nanofluid flow, it is found that the nanofluid velocity falls as the Deborah number, Darcy number, non-Darcy number, and suction/injection parameter increase. On the other hand, buoyancy-driven acceleration is promoted by nonlinear convection, nonlinear solutal convection parameters, and increased thermal and solutal Grashof numbers, all of which increase velocity. It is found that increasing the Eckert number, heat generation parameter, thermal radiation, Biot number, Brownian motion, Dufour effect, and thermophoresis—all of which lead to increased thermal energy accumulation—significantly raises the nanofluid temperature. moreover, thermal stratification and a greater Prandtl number cause temperature to drop because of less thermal diffusion. Additionally, as Lewis number, Brownian motion, thermophoresis, stratification, and chemical reaction parameters increase, solute concentration decreases, suggesting either improved mass diffusion or species depletion. However, as the Soret and Biot numbers rise, the concentration rises as well, suggesting boundary resistance and thermally induced mass flux. These results offer useful recommendations for improving heat/mass transfer and nanofluid flow in manufacturing, chemical, and energy systems.

Practical implications

The outcomes demonstrate that cubic stratification greatly improves mass and heat transmission in chaotic mixed convection flows, highlighting its critical significance in cutting-edge thermal management applications like medicinal devices, renewable energy systems, and electronics cooling. The model is further enhanced by the incorporation of cross-diffusion processes, particularly the Soret and Dufour effects, which capture the coupled mass transfer and heat mechanisms common in nanofluid flows. Because of their extraordinary thermal characteristics, nanofluids are still essential for improving cooling systems and encouraging environmentally friendly practices. Additionally, adding stratification effects increases thermal energy storage systems’ efficiency, which results in significant energy savings and improved economic feasibility. All of these observations highlight the model’s usefulness in creating heat transfer systems that are more efficient and energy-efficient.

Future directions

In order to improve thermal performance, future research may investigate hybrid, tri-hybrid, and penta-hybrid nanofluids. More realistic modeling can be achieved by include a variety of boundary conditions, including melting heat transfer, Newtonian heating, and slip types. This approach will be more applicable if it is extended to Carreau, Oldroyd-B, or Williamson fluids non-Newtonian models and complex geometries (such curved, or wavy surfaces). Optimizing parameters and increasing forecasting accuracy are further benefits of incorporating machine learning techniques. Last but not least, experimental validation is necessary to validate numerical results and facilitate industrial application.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Choi, S. U. S. Nanofluid Technology: Current Status and Future Research (Argonne National Lab.(ANL), 1998). Argonne, IL (United States).

Buongiorno, J. Convective transport in nanofluids (2006).

Reza-E-Rabbi, S., Ahmmed, S. F., Arifuzzaman, S., Sarkar, T. & Khan, M. S. Computational modelling of multiphase fluid flow behaviour over a stretching sheet in the presence of nanoparticles. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 23 (3), 605–617 (2020).

Reza-E-Rabbi, S., Arifuzzaman, S., Sarkar, T., Khan, M. S. & Ahmmed, S. F. Explicit finite difference analysis of an unsteady MHD flow of a chemically reacting Casson fluid past a stretching sheet with brownian motion and thermophoresis effects. J. King Saud Univ. -Sci. 32 (1), 690–701 (2020).

Ratha, P. K., Mishra, S., Tripathy, R. & Pattnaik, P. K. Analytical approach on the free convection of Buongiorno model nanofluid over a shrinking surface, Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part N J. Nanomater. Nanoeng. Nanosyst.. 237(3–4), 83–95 (2023).

Baag, S., Panda, S., Pattnaik, P. & Mishra, S. Free convection of conducting nanofluid past an expanding surface with heat source with convective heating boundary conditions. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 44 (1), 880–891 (2023).

Pattnaik, P. K., Abbas, M. A., Mishra, S., Khan, S. U. & Bhatti, M. M. Free convective flow of hamilton-crosser model gold-water nanofluid through a channel with permeable moving walls. Comb. Chem. High. Throughput Screen. 25 (7), 1103–1114 (2022).

Yousif, M. A., Ismael, H. F., Abbas, T. & Ellahi, R. Numerical study of momentum and heat transfer of MHD Carreau nanofluid over an exponentially stretched plate with internal heat source/sink and radiation. Heat Transf. Res. 50, 7 (2019).

Shafique, Z., Mustafa, M. & Mushtaq, A. Boundary layer flow of Maxwell fluid in rotating frame with binary chemical reaction and activation energy. Results Phys. 6, 627–633 (2016).

Panda, S., Baithalu, R., Baag, S. & Mishra, S. Behaviour of effective heat transfer rate in radiating micropolar nanofluid over an expanding sheet with slip effects. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 11, 100851 (2024).

Panda, S., Ontela, S., Mishra, S. & Thumma, T. Effect of arrhenius activation energy on two-phase nanofluid flow and heat transport inside a circular segment with convective boundary conditions: Optimization and sensitivity analysis. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B. 38 (25), 2450342 (2024).

Uddin, I., Ullah, I., Ali, R., Khan, I. & Nisar, K. Numerical analysis of nonlinear mixed convective MHD chemically reacting flow of Prandtl–Eyring nanofluids in the presence of activation energy and joule heating. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 145, 495–505 (2021).

Balamurugan, R. & Vanav Kumar, A. Mixed convection of transient MHD stagnation point flow over a stretching sheet with quadratic convection and thermal radiation. Heat. Transf. 53 (2), 584–609 (2024).

Khan, M., Zhang, Z. & Lu, D. Numerical simulations and modeling of MHD boundary layer flow and heat transfer dynamics in Darcy-forchheimer media with distributed fractional-order derivatives. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 49, 103234 (2023).

Khan, M., Rasheed, A., Anwar, M. S. & Shah, S. T. H. Application of fractional derivatives in a Darcy medium natural convection flow of MHD nanofluid. Ain Shams Eng. J. 14 (9), 102093 (2023).

Khan, M., Lone, S. A., Rasheed, A. & Alam, M. N. Computational simulation of Scott-Blair model to fractional hybrid nanofluid with Darcy medium. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 130, 105784 (2022).

Patil, P. M., Shankar, H. F. & Sheremet, M. A. Quadratic mixed convective nanofluid flow past a moving yawed cylinder in the presence of thermal radiation and diffusive liquids. Heat Transf. 51 (5), 4306–4330 (2022).

Patil, P. & Goudar, B. Quadratic combined convective flow about yawed cylinder in presence of time variations and magnetic effects: entropy analysis. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 44 (1), 1047–1057 (2023).

Patil, P. & Goudar, B. Entropy generation analysis from the time-dependent quadratic combined convective flow with multiple diffusions and nonlinear thermal radiation. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 53, 46–55 (2023).

Hayat, T., Ali, N. & Asghar, S. Hall effects on peristaltic flow of a Maxwell fluid in a porous medium. Phys. Lett. A. 363, 5–6 (2007).

Khan, N. M., Chu, Y. M., Ijaz Khan, M., Kadry, S. & Qayyum, S. Modeling and dual solutions for magnetized mixed convective stagnation point flow of upper convected Maxwell fluid model with second-order velocity slip. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. (2020).

Khan, M. N., Nadeem, S., Ahmad, S. & Saleem, A. Mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in a Maxwell fluid, Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci.. 235(20), 4967–4976 (2021).

Muhammad, T., Alsaedi, A., Shehzad, S. A. & Hayat, T. A revised model for Darcy-Forchheimer flow of Maxwell nanofluid subject to convective boundary condition. Chin. J. Phys. 55 (3), 963–976 (2017).

Khan, M., Malik, M., Salahuddin, T., Saleem, S. & Hussain, A. Change in viscosity of Maxwell fluid flow due to thermal and solutal stratifications. J. Mol. Liq. 288, 110970 (2019).

Ahmad, S., Khan, M. N. & Nadeem, S. Mathematical analysis of heat and mass transfer in a Maxwell fluid with double stratification. Phys. Scr. 96 (2), 025202 (2020).

Pattnaik, P. K., Mishra, S. R., Panda, S., Syed, S. A. & Muduli, K. Hybrid methodology for the computational behaviour of thermal radiation and chemical reaction on viscoelastic nanofluid flow, Math. Probl. Eng. 2022(1), 2227811 (2022).

Ding, X., Zhang, F., Zhang, G., Yang, L. & Shao, J. Modeling of hydraulic fracturing in viscoelastic formations with the fractional Maxwell model. Comput. Geotech. 126, 103723 (2020).

Subbarao, K., Elangovan, K. & Gangadhar, K. Entropy analysis in a second-grade nanoliquid influenced by an exponential space-dependent heat source and arrhenius activation energy. Heat Transf. 51 (6), 5679–5699 (2022).

Gangadhar, K. et al. Heat transport magnetization for burgers fluid in a porous medium with convective heating and heterogeneous-homogeneous response. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 48, 103087 (2023).

Panda, S., Baag, A. P., Pattnaik, P., Baithalu, R. & Mishra, S. Artificial neural network approach to simulate the impact of concentration in optimizing heat transfer rate on water-based hybrid nanofluid under slip conditions: A regression analysis. Numer. Heat Transf. Part B Fundam. 1–23 (2024).

Tinker, S., Mishra, S., Pattnaik, P. & Sharma, R. P. Simulation of time-dependent radiative heat motion over a stretching/shrinking sheet of hybrid nanofluid: Stability analysis for dual solutions, Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part N J. Nanomater. Nanoeng. Nanosyst. 236(1–2), 19–30 (2022).

Pattnaik, P., Mishra, S., Shamshuddin, M., Panda, S. & Baithalu, R. Significant statistical model of heat transfer rate in radiative Carreau tri-hybrid nanofluid with entropy analysis using response surface methodology used in solar aircraft. Renew. Energy. 237, 121521 (2024).

Shamshuddin, M. et al. Diversified characteristics of the dissipative heat on the radiative micropolar hybrid nanofluid over a wedged surface: Gauss-Lobatto IIIA numerical approach. Alex. Eng. J. 106, 448–459 (2024).

Mishra, S., Panda, S. & Baithalu, R. Enhanced heat transfer rate on the flow of hybrid nanofluid through a rotating vertical cone: A statistical analysis. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 11, 100825 (2024).

Sekine, M., Tsukamoto, N., Masuhara, Y. & Furuya, M. Experimental study on thermal stratification in water pool with vertical heat source. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 207, 110681 (2024).

Muzammal, M., Farooq, M., Alotaibi, H. & others. Transportation of melting heat in stratified Jeffrey fluid flow with heat generation and magnetic field. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 58, 104465 (2024).

Ahmad, S., Hafeez, M. & Farooq, M. Investigation of variable thermal relaxation time in non-Fourier heat transfer flow with nonlinear thermal stratification, Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 238(2), 810–818 (2024).

Shi, Q. H., Khan, M. N., Abbas, N., Khan, M. I. & Alzahrani, F. Heat and mass transfer analysis in the MHD flow of radiative Maxwell nanofluid with non-uniform heat source/sink. Waves Random Complex. Media. 34 (4), 3450–3473 (2024).

Jabeen, I., Farooq, M., Rizwan, M., Ullah, R. & Ahmad, S. Analysis of nonlinear stratified convective flow of Powell-Eyring fluid: Application of modern diffusion. Adv. Mech. Eng. 12 (10), 1687814020959568 (2020).

Malik, H. T., Farooq, M. & Ahmad, S. Significance of nonlinear stratification in convective Falkner-Skan flow of Jeffrey fluid near the stagnation point. Int. Commun. Heat Mass. Transf. 120, 105032 (2021).

Panda, S., Ontela, S., Thumma, T., Mishra, S. & Pattnaik, P. Mechanism of heat transfer in Falkner–Skan flow of buoyancy-driven dissipative hybrid nanofluid over a vertical permeable wedge with varying wall temperature. Mod. Phys. Lett. B. 38 (01), 2350211 (2024).

Khan, Q., Farooq, M. & Ahmad, S. Convective features of squeezing flow in nonlinear stratified fluid with inclined rheology. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 120, 104958 (2021).

Shafiq, A., Çolak, A. B., Sindhu, T. N. & Muhammad, T. Optimization of Darcy-Forchheimer squeezing flow in nonlinear stratified fluid under convective conditions with artificial neural network. Heat Transf. Res. 53, 3, (2022).

Rehman, K. U. & Shatanawi, W. Thermal analysis on mutual interaction of temperature stratification and solutal stratification in the presence of non-linear thermal radiations. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 35, 102080 (2022).

Sreedevi, P. & Reddy, P. S. Unsteady boundary layer heat and mass transfer flow of nanofluid over porous stretching sheet with non-uniform heat generation/absorption and double stratification. J. Nanofluids. 12 (8), 2067–2077 (2023).

Santhi, M., Rao, K. S., Reddy, P. S. & Sreedevi, P. Heat and mass transfer analysis of steady and unsteady nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with double stratification. Nanosci. Technol. Int. J. 10, 3 (2019).

Alrihieli, H., Aldhabani, M. S., Alshaban, E. & Alatawi, A. Thermal-hydrodynamic analysis of a Maxwell fluid with controlled heat/mass transfer over a Riga plate: A numerical study with engineering applications. Results Eng. 26, 104801 (2025).

Afridi, M. I., Almohsen, B., Habib, S., Khan, Z. & Razzaq, R. Artificial neural network analysis of MHD Maxwell nanofluid flow over a porous medium in presence of joule heating and nonlinear radiation effects. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 192, 116072 (2025).

Konda, J. et al. Combined viscous dissipation and joule heating effects on chemically radiative MHD micropolar flow with heat source and convective boundary conditions. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects. 41, 101434 (2025).

Thumma, T., Mishra, S., Pattnaik, P. & Reddy, C. A. Exploring MHD radiative Maxwell nanofluid flow on an expanding surface for the impact of activation energy associated with velocity slip and convective boundary conditions. J Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1–21 (2025).

Syam, M. M., Morsi, F., Eida, A. A. & Syam, M. I. Investigating convective Darcy–Forchheimer flow in Maxwell nanofluids through a computational study. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 11, 100863 (2024).

Sangeetha, E., De, P. & Das, R. Hall and ion effects on bioconvective Maxwell nanofluid in non-darcy porous medium. Spec. Top. Rev. Porous Media Int. J. 14, 4 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through grant number: 25UQU4240148GSSR03.

Funding

This research work was funded by Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia under grant number: 25UQU4240148GSSR03.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions, Conceptualization: Abbas khan, Formal analysis: Hashim, Investigation: Muhammad Farooq, Methodology: Muhammad Amer Qureshi, Software: M. Prakash, Re-Graphical representation & Adding analysis of data: Bandar M. Fadhl, Writing - original draft: Kamel Guedri, Writing - review editing: Abdulrazak H. Almaliki, Numerical process breakdown: Bandar M. Fadhl, Re-modelling design: Hashim & Bandar M. Fadhl, Re-Validation: Mustafa Bayram & Bandar M. Fadhl.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

khan, A., Hashim, Farooq, M. et al. Quadratic mixed convection of Maxwell-Buongiorno nanofluid over cubic stratified surface incorporating cross diffusion effects and solar radiation. Sci Rep 15, 20092 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07140-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07140-0