Abstract

Human eye blinks are considered a significant contaminant or artifact in electroencephalogram (EEG), which impacts EEG-based medical or scientific applications. However, eye blink detection can instead be transformed into a potential application of brain–computer interfaces (BCI). This study introduces a novel real-time EEG-based framework for classifying three blink states: no blink, single blink, and two consecutive blinks in one model. EEG data were collected from ten healthy participants using an 8-channel wearable headset under controlled blinking conditions. The data were preprocessed and analyzed using four feature extraction techniques: basic statistical, time-domain, amplitude-driven, and frequency-domain methods. The most significant features were selected to develop three machine learning models: XGBoost, support vector machine (SVM), and neural network (NN). We achieved the highest accuracy of 89.0% for classifying multiple-eye blink detection. To further enhance the model’s capacity and suitability for real-life BCI applications, we trained and employed the You Only Look Once (YOLO) model, achieving a recall of 98.67%, a precision of 95.39%, and mAP50 of 99.5%, demonstrating its superior accuracy and robustness in classifying two consecutive eye blinks. In conclusion, this study will be the first groundwork and open a new dimension in EEG-based BCI research by classifying multiple-eye blink detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Brain–computer interface (BCI) is a non-invasive communication model between the human brain and a computerized system1. Electroencephalographic (EEG) signals2,3 are among the most popular methods in BCI applications. Eye blink detection using EEG signals can be useful for many BCI applications. In the literature, the detection of eye blinks is used as an artifact and removal from BCI applications; however, detecting eye blinks can play a vital role in this area. However, some of the research work has been done in this area, but they are only limited to the detection of single eye blinks; no such work has been found to detect multiple eye blinks (no eye blink, single eye blink, and two consecutive eye blinks). In this work, we have designed and developed a deep learning-based model from our collected datasets to detect multiple eye blinks with a recall of 98.67%, a precision of 95.39%, and an mAP50 of 99.5%. This shows the robustness and readiness for deployment of this model in real-life BCI applications. At the end of this study, we also demonstrated a proposal BCI architecture, where we can apply our developed and validated model.

Introduction

Brain–computer interface (BCI) is a real-time and non-invasive human brain-controlled model that communicates with a computerized system by acquiring, analyzing, and translating brain activity1. At first, a computer scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Jacques Vidal, devised the term “BCI” in the 1970s when he demonstrated that the human brain could control a cursor through a virtual maze4. Since that time, BCI has been popular in both computer technology and neuroscience areas. Several BCI systems have been invented in this area, such as electroencephalographic (EEG) signals2,3, magnetoencephalography (MEG)5, electrocorticography (ECoG)6, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)7, functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIR)8, and so on. The human eye blink is usually considered an artifact in the EEG signal, and several techniques have been discovered to detect the eye blink9,10. However, human eye blinks can be a potential candidate in EEG-based BCI11 to enhance communication for individuals with a verbal disability or severe motor impairments12. Besides that, on the raw EEG signal, the eye blinks are clearly shown and addressed.

The development of this system is inspired by a compelling real-life case of a patient with traumatic brain injury in an intensive care unit (ICU). Although the patient was unable to speak or move, her cognitive functions remained intact. In a final interaction, her child asked her to blink if she could recognize him—an act she performed before passing away. This moment underscored the untapped communicative potential of eye blinks. Our proposed framework aims to transform such moments into actionable communication channels, offering both a practical solution for individuals with disabilities and a new direction for multi-blink EEG-based BCI design.

Several research works have been accomplished in this area to classify eye blinks. However, most of them are for detecting and removing the eye blink events, considering them as an artifact. Few of the works classify eye blinks for BCI application, but all of them focus on only a single eye blink. Extensive scientific literature has demonstrated that neural signals can reliably infer intentionality in the absence of observable communicative behaviors13. Among them, some of the studies classified eye blinks as intentional or unintentional11,14,15,16.

In this work, at first, we did a Scopus review of the previous work and identified the research gaps to classify no blink (0b), single blink (1b), and consecutive two blinks (2b) from EEG signals for developing a real-time BCI application. Moreover, we analyzed our collected EEG signal using four renowned feature extraction techniques (i. Basic Statistical Features, ii. Time-Domain Features, iii. Amplitude-Driven Features, and iv. Frequency Domain Features) to identify the most prominent features for classifying the multiple eyeblinks. We built three machine-learning models (XGBoost17,18, Support Vector Machine (SVM)19, and Neural Network (NN)20) using the selected features and got the highest accuracy of 89.0% for classifying multiple-eye blink detection. From our experiment, we observed that the traditional machine learning models suffer from classifying eye blink (0b, 1b, or 2b) when multiple occurrences of any blink appear within a single timeframe. This is an important requirement for real-time EEG-based BCI applications. To overcome these challenges, we trained and built the YoLo model21,22, which effectively classifies multiple eye blinks (0b, 1b, or 2b) even when they occur repeatedly within a single timeframe. In summary, our work makes the following contributions:

-

A scopus review of previously published work (n = 29) in this area and identification of research gaps.

-

Collection of EEG signals for eye blink (0b, 1b, or 2b) data from 10 healthy individuals using the Ultracortex “Mark IV”23 8-channel EEG headset under the Institutional Review Board approval (Protocol #HR-4640).

-

Analyzing the raw EEG signal and selecting the most important features for building machine learning models.

-

Training four machine learning models [XGBoost, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Neural Network (NN)] to classify multiple eye blinks and find the limitations.

-

Designing and developing a novel approach by using the YOLO model to build a robust EEG-based BCI application for accurate multiple-eye blink classification.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. “Related works” reviews the previous works, providing context for this study. “Method” describes the methodology employed to design and implement the proposed system. “Discussion” describes the results and highlights the findings. “Impact and challenges” illustrates the potential applications of the system and challenges encountered during the study. Finally, “Conclusion” concludes the paper.

Related works

Research has been done to remove Eye Blink Artifacts (EBAs) to provide cleaner data for analysis of EEG signals for various purposes, ranging from driver fatigue detection to biometric authentication24,25. Several studies have devised frameworks for detecting the eye blink events related to the delta area of the human brain, with some exclusively focusing on real-time detection26,27,28,29.

Interestingly, few researchers performed binary classification of the eye blink events into intentional and unintentional eye blink11,14,15,16. This was based on the fact that intentional and unintentional eye blinks have been characterized by distinct waveforms of the electrooculogram (EOG) and the electromyogram (EMG), with the intentional blinking exhibiting a significantly greater amplitude as compared to the spontaneous eye blinks30,31,32 as intentional and spontaneous blinking are preceded by different brain activities. One study advanced the detection event by undertaking the task of distinguishing cases of eye blinking and open eyes33. We summarize the related work into the following subcategories:

Eye blink artifacts (EBAs) removal

Summarization on multi-channel EEG

Tibdewal et al. emphasized capturing 16-channel EEG data to diagnose brain disorders, including epilepsy, sleep disorders, coma, and brain death34. They used a combination of Artificial Neural Network (ANN) for binary classification of artifactual and non-artifactual signals, and Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) for contaminated zone detection. By employing DWT, they were able to decompose the EEG signal into different frequency components, allowing for the identification of peaks and drops that correspond to eye blinks. Without DWT, there is a risk that artifact removal might eliminate important cerebral activity. The ANN achieved an accuracy of 95.83%, with 98.21% Sensitivity, and 87.50% Specificity.

Suguru et al. captured 14-channel EEG signals and vertical EOG signals and employed Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to separate the recorded EEG signals into estimated artifact signals and intrinsic EEG signals35. They relied on Positive Semidefinite Tensor Factorization (PSDTF) to extract features of eye-blink artifacts by analyzing the similarities in their waveforms, creating templates for accurate artifact removal. They reported a high signal-to-noise ratio (15.03 dB) and a low mean square error (25.76).

Ranjan et al. extracted only intentional eye blinks after tracking an eye blink of a person from EEG signal sequences16. The EEG data were recorded using a three-electrode setup (SS2L), resulting in two channels of information. Two electrodes captured signals from distinct brain locations (FP1–F3 or FP2–F4), while the third served as a reference point at the ear. By integrating a band-pass filter to limit frequencies between 0.5 and 15 Hz, followed by a comparator to detect eye blinks by comparing the amplified signal against a reference voltage, they found a high output signal whenever an eye blink occurs.

Kleifges et al. proposed BLINKER, an automated pipeline that uses EEG data, EOG channels, and independent components for blink detection36. They have analyzed a large corpus of EEG data comprising more than 2000 datasets acquired at eight different laboratories, and another dataset (BCI-2000) with a 64-channel headset. By applying band-pass filtering and thresholding, their study identifies and groups blinks, removes outliers, and calculates ocular indices, facilitating large-scale analysis of blink variability related to fatigue and attention.

Tran et al. performed amplitude thresholding of EEG signals37. This method uses six ocular features from bilateral channels to identify various eye blinks and movements with high speed and 88% average accuracy. However, it requires individual calibration and shows lower accuracy for eye movement detection.

Kong et al. formulated an adaptive filtering for eye blink artifact removal without losing critical neural information38. Sixty-two channels of EEG data from 35 subjects, including diverse experimental conditions with 80% signal contamination by blinks, were collected. They developed an adaptive filtering technique, reducing artifacts by 90% while retaining 95% of the original signal information. Ensuring the method’s adaptability across varied electrode setups and subject-specific signal profiles remains challenging for this study.

Rao et al. address the significant issue of ocular artifacts (OAs) corrupting EEG signals, hindering clinical analysis39. They proposed an energy detection method to identify blink regions and apply wavelet thresholding to these areas, aiming to preserve neural data in non-blink segments. The study compares various Wavelet Transform (WT) techniques and threshold functions using metrics like Artifact Rejection Ratio (ARR) and Correlation Coefficient (CC). The Stationary Wavelet Transform (SWT) demonstrates a notable advantage over the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) in artifact removal, exhibiting an approximate 18% improvement in the ARR, indicating a greater ability to eliminate artifacts. Furthermore, SWT achieves about a 21% reduction in the CC, suggesting a better separation from the original noisy signal after processing.

Moreover, Wahab et al. collected 40 EEG recordings of 1 subject for a Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) system that interprets user intent by analyzing EEG signals over four channels29. Their methodology involves strategically placing electrodes (Fp1/Fp2 for actual, C3/C4 for imagined blinks) to capture relevant brain activity using the wireless OpenBCI EEG recording system. Signal processing algorithms are crucial: averaging enhances signal amplitude, a high-pass filter (0.5 Hz cutoff) removes baseline drift, and a FIR band-pass filter (0.5–2 Hz) isolates blink information while eliminating noise. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is then applied to analyze the frequency content of both actual and imagined blink EEG signals, revealing similar frequencies but distinct amplitude ranges. This algorithmic approach allows the BCI to differentiate between these intentional and unintentional signals for potential control applications.

Summarization on single-channel EEG

Sammaiah et al. emphasized the detection and determination of eye blinks from Electro-oculography (EOG) signals to be utilized for wheelchair control, cursor control, and home automation40. They paired signal-conditioned EOG signals with a wavelet-based method to utilize multi-resolution analysis through wavelet decomposition into four levels to effectively denoise EOG signals. They reported 100% Sensitivity, while 95.23% Specificity.

Shahbakhti et al. utilize a single prefrontal EEG channel (Fp1) data for the identification of eye blink intervals using a moving standard deviation algorithm, and filtering of EEG signals with DWT24. Their method demonstrates high reliability, achieving sensitivity of 90.2%, specificity of 87.7%, and accuracy of 88.4% when tested with different databases using the AdaBoost classifier for driver fatigue detection.

A five-sample window-mean thresholding technique was engineered by Jefri et al. to identify potential eye blink regions within the EEG signal, and the eye blink components were extracted from the identified regions using an energy threshold41. Finally, a Recursive Least-Mean Square (RLS) adaptive filter was utilized to effectively remove the extracted eye blink component from the EEG signal, minimizing alterations to the original brain activity data. The method achieved a good Root Mean-Square Error (RMSE) of 0.3211 ± 0.2738 for the cleaned EEG signal, along with a high Correlation Coefficient (CC) of 0.9430 ± 0.0839 between the cleaned EEG signal and the original signal.

Researchers have formulated a hardware-based configurable algorithm for eye blink detection to demonstrate how their field-programmable gate array (FPGA) implementation outperformed the proprietary Neurosky software15. A single-channel EEG data from the NeuroSky headset, visualized with and without blinks, reveals a distinct, low-frequency, high-amplitude waveform during blinks. Detecting this artifact, distinguishable from brain activity by its amplitude and frequency, necessitates a differentiator and a low-pass filter. The strength of the study lay in the fact that their algorithm effectively identified intentional and unintentional blinks, coupled with the ability to handle varying blink strengths without data loss.

Summarization on machine learning

The usage of Support Vector Machine (SVM) is prevalent in research focused on eye blink detection from EEG signals42,43.

Gupta et al. detected eye movements and blinks from EEG signals recorded from the brain’s frontal region42. They extracted features using the Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) and adopted SVM to map them to corresponding eye movements and blinks with 97% accuracy.

Ghosh et al. introduce a novel automated method for detecting and correcting eye blink artifacts in EEG signals, overcoming limitations of traditional ANC and DWT techniques that often require manual intervention43. The proposed approach employs a sliding window and a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier to automatically identify artifactual segments. Subsequently, an autoencoder is used to correct these identified artifacts. A classifier was trained on a balanced dataset of 2000 EEG segments, with 1000 containing eye blink artifacts and 1000 being clean. Its performance was then evaluated using a separate test set comprising 100 segments from each of the two classes. The method demonstrates superior performance (98.4% accuracy, 99.1% sensitivity, and 97.2% specificity) in both identifying and removing artifacts compared to existing wavelet and ANC-based methods. Notably, it eliminates the need for ICA preprocessing and can be applied to multiple channels concurrently.

Ferrari et al.44 classified clean EEG signals and those contaminated by eye blink artifacts by training their model with eye movement data from voluntary blinking, watching videos, and reading articles. They presented a reliable, user-independent algorithm using a CNN to detect and remove these artifacts, overcoming the limitations of traditional methods that often require complex equipment and many electrodes. The CNN model, trained and validated on three public EEG datasets involving these tasks, effectively distinguishes clean signals from artifact-contaminated ones without overfitting.

Real-time BCI applications for assistive communication

For individuals with motor disabilities, including those with ALS (as mentioned in a previous turn), intentional eye blinks can be a reliable and controllable physiological signal. Leveraging these blinks for authentication can provide a hands-free and potentially less cognitively demanding method of secure access to assistive communication technologies. The removal of eye blink noise from EEG signals was performed by Matiko et al.45 and Renato et al.27 using single-channel EEG data. Additionally, real-time eye blink classification methods were introduced for detecting eye blinks from single-channel EEG signals by Zhang et al. in their RT-Blink method26 and Wahab et al.29. We describe such research work under this subsection of the paper.

Summarization on signal processing and filtering techniques

Renato et al.27 discussed the real-time detection of eye blink patterns in single-channel EEG signals using wavelet transform. This algorithm analyzed EEG data within a moving 256-sample window to identify eye blink artifacts, characterized by a positive maximum and negative minimum, regardless of their scale or frequency. Wavelet transform enables multi-resolution analysis, critical for detecting variable blink patterns. In this research, real-time EEG data were obtained from a single channel, concentrating on the FP1 and FP2 polar frontal regions of the scalp. The EEG signals were captured at a sampling rate of 512 Hz using a dry electrode from Neurosky’s Mindset device. The authors aim to translate voluntary eye blinks into commands for assistive technologies, enhancing brain-computer interface applications by providing robust real-time detection of these specific EEG artifacts.

Matiko et al. resorted to Morphological Component Analysis (MCA), suitable for resource-constrained environments, and tested on over 60 frames of single-channel EEG data45. With the help of MCA, the EEG signal was decomposed into components to separate eye blink noise from the underlying brain activity. Short Time Fourier Transform (STFT) aided sparse representation of EEG and eye blink signals, leading to fast computation and reduced memory requirements. Renato et al. collected EEG data from a single channel, specifically focusing on the polar frontal areas FP1 and FP2, at a sampling frequency of 512 samples per second. The system processes EEG signals through a moving analysis window, identifying artifacts based on their unique shape and amplitude characteristics.

Nguyen et al. devised a mean threshold algorithm in which they proposed a threshold method to determine which value can be used to distinguish eye blinking and open-eye cases33. To minimize noise and artifacts, they applied a band-pass filter to the data, targeting the delta frequency range (0.5 to 3.5 Hz) at the Fp2 electrode position—an area associated with eye-related brain activity. With a sample size of 2,500, they first calculate the average signal value for the opened eye condition and the standard deviation of the signal in the opened eye state. This threshold plays a vital role in distinguishing eye blinks from normal eye-open states based on amplitude fluctuations in the delta signal. Moreover, it has utility in controlling external devices and systems in BCI applications by mapping blink events to specific commands and facilitating studies on eye-blink dynamics in cognitive neuroscience and BCIs.

A three-part learning system for feasible EEG data annotation, segmentation, and discriminative eye blink detection through automatic scoring, multi-score clustering was proposed by Dehzangi et al.46. This study aimed at detecting blink noise in continuous trials during long and complex tasks from 7 EEG channels and without any EOG recording. Here, unlabeled EEG data is annotated using Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) to align it with blink pattern templates, generating initial labels. Afterward, K-means clustering is applied to the DTW multi-score space to categorize segments as blink or non-blink. An SVM is then trained to create a discriminative detection hyperplane. Experiments on EEG data from multiple channels showed that frontal channels, particularly Fz, yielded the highest accuracy of 96.42%.

Summarization on machine learning

Liu et al. developed a hybrid BCI system based on eye blinks to facilitate seamless control of assistive devices through eye movements for people with motor impairments12. Electrooculogram (EOG) signals integrated with EEG recordings were utilized for analysis by combining machine learning and thresholding techniques to classify eye blinks and voluntary actions with improved precision. Although synchronizing multiple signal modalities while maintaining low latency and high reliability poses an insurmountable challenge for the study.

Researchers have employed CNN for eye blink detection under various conditions. When discriminating the blinks performed by the subjects (voluntary vs. involuntary), one model showed an average accuracy of 97.92%28.

The potential of eye blink artifacts as a robust and practical biometric trait for EEG-based authentication systems was demonstrated by Thamang et al.25. In their study with 10 subjects (five adult females and males aged 20–35 years), brain waves were recorded by maneuvering the NeuroSky Mindwave Mobile 2 headset, and eye blink features were extracted from single-channel EEG data through NeuroSky’s blink detection algorithm. Consequently, a pattern-matching-based authentication algorithm was developed considering the blink strength, time, and frequency inputs. The proposed method demonstrated high performance with an accuracy (ACC) of 97%.

Farago et al. explored extracting ocular data (blink and saccade rates) from forehead EEG recordings to assess cognitive state, contrasting with the traditional view of ocular artifacts as noise47. They developed regression models and validated against simultaneously recorded EOG during Multi-Attribute Task Battery simulations at varying workload levels47. Blinks were detected in 45 EEG segments per participant with 81% precision and 79% recall, showing consistent rates and workload-related patterns. The predicted EOG signals showed strong correlations (0.72–0.94) with actual EOG. Blink rates derived from EEG mirrored EOG-based rates across workloads, while saccade rate analysis showed more inter-subject variability. The study suggests that linear regression can effectively extract useful ocular information from forehead EEG, potentially offering a less cumbersome method for cognitive state monitoring compared to traditional EOG.

RT-Blink employs a short, windowed approach for efficient processing, incorporating a random forest classifier with multiple features and a potential blink boundary detection26. They experimented by varying the time window sizes, starting from 4 to 40, and found out that Smaller window sizes enable quicker blink detection with less delay due to finer granularity, but require more computation. Furthermore, it achieved high performance with an average sensitivity of 96.54% and precision of 91.25% in blink detection. The method demonstrated an average processing time of 5.07 ms per 60 ms time window.

To detect intentional eye blink signals from EEG signals, Rihana et al. focused on the frontal lobes where these signals are primarily detected and acquired EEG signals from six subjects using a BioRadio portable device14. Their work addressed the communication challenges encountered by individuals with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). The BCI framework was pivotal to their concept, as they investigated the use of intentional eye blinks as a control signal to activate a graphical user interface, thereby facilitating communication through the usage of a Radial Basis Function (RBF) classifier.

Building upon the need for BCI-based control via eye movements, Giudice et al. introduced a deep learning system11 to automatically detect and translate intentional eye blinks. A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) was developed to classify natural, forced, and no blinks, achieving 99.4% accuracy. The study’s focus was to use Explainable Artificial Intelligence (xAI) techniques like Grad-CAM and LIME to understand which EEG segments are most relevant for distinguishing voluntary from involuntary blinks. The xAI analysis visually highlighted key EEG areas for each blink type. For natural blinks, the critical period was from eye closure to reopening, while the opposite was true for voluntary blinks. Baseline activity showed low activation.

As previously noted, all the studies are limited by the lack of provisions for detecting two consecutive blinks simultaneously. We demonstrate our literature review in Fig. 1, in the form of a taxonomy tree. In the taxonomy tree, we divided the survey studies into four major fields (Background, ML algorithm, Application, and Electrode number) and their subfields. The leaf nodes of the tree represent a single research work.

Comparative summarization of related work

Based on our survey, we summarized the previous studies into the following Table 1 by their methodology, results, and findings.

Method

Our proposed methodology is divided into two parts: (i) Classical machine learning and (ii) Deep learning for detecting eye blinks (0b, 1b, 2b).

Classical machine learning models for eye blink detection

The overall workflow for detecting eye blinks from EEG signals by the classical machine learning models is shown in Fig. 2.

Step 1: Data collection: We have collected EEG data from 10 healthy participants (Male: 5 and Female: 5) aged between 20 and 35 years (average age: 27.5 Years) with their consent under a controlled environment in Ubicomp Lab48, Marquette University, USA. The data was collected by using an Ultracortex “Mark IV” 8-channel EEG headset23 and different questionnaires with no blink, single blink, and two consecutive blinks to level the EEG signal for eye blinks. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Marquette University (Protocol #HR-4640).

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. We have conducted three different sessions (30 min duration for each session) for each participant. For a single session, we collected 29,520 EEG data points, so in total, from all sessions (n = 3) and participants (10), we have a total of 885,600 EEG data points in our dataset for eye blink detection. Figure 3 shows the data collection setup and prototype for this study.

Step 2: Preprocessing: In this step, we examined our collected EEG data for missing data points and any outliers. After a thorough analysis, we confirmed the absence of missing values or outliers in the collected dataset. According to research, the human frontal lobe, particularly the prefrontal cortex, plays an important role in controlling eye blinking49,50, as shown in Fig. 4a. We can obtain frontal brain activity through the Frontal pole left (Fp1) and Frontal pole right (Fp2), which are sensitive to detecting eye blinks. Figure 4b illustrates the EEG Electrode placement for the Ultracortex “Mark IV” 8-channel EEG headset23.

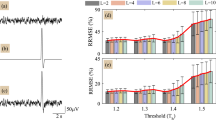

According to the theoretical and research findings, we examined channel one (in Fig. 5a) and channel two in Fig. 5b raw EEG data and identified significant patterns corresponding to no eye blinks (marked by black boxes), one eye blink (marked by red boxes) and two consecutive eye blinks (marked by blue boxes) on both channel one and channel two’s raw EEG data points. The height between one eye blink (1b) and two consecutive eye blinks (2b) EEG signals is noticeably higher than that of no blink (0b) for both channels. That means the amplitude of the 1b and 2b is higher than 0b. Additionally, a significant finding of the pattern between one eye blink (1b) and two consecutive eye blinks (2b) is the width of the raw EEG signal between them. For both channels, we observed that the 2b EEG signal’s width (marked by a green line) is larger than 1b. This is the main significant ground-level finding for classifying 1b and 2b. Figure 5 illustrates the raw EEG signal for the same participant from channels 1 and 2.

Step 3: Feature extraction: Feature extraction is the pivotal step in this study to analyze the EEG signal for detecting eye blinks (0b, 1b, and 2b) using the classical machine learning algorithms. According to step 2’s findings, we only considered channel one and channel two’s data for feature extraction. We have used all 10 participants’ channel 1 and channel 2 EEG data for this feature extraction analysis. We have used four different types of signal analysis algorithms to extract the signal’s features for classifying the eye blinks.

Basic statistical features

In this analysis, we determine three types of signal parameters for both channels51. An overview of the box plot for no blink, one eye blink, and two eye blinks is demonstrated in Fig. 6. Here are the following three parameters:

Standard Deviation (Std): It measures the variability or dispersion of the EEG signal. This parameter’s data is important for sudden changes in EEG data caused by eye blinks. Channel one and two’s standard box plots are shown in Fig. 6a,b, respectively.

Maximum (Max) and Minimum (Min): This parameter represents the peak and trough points of the EEG signal for no blink, one eye blink, and two eye blinks. These parameters are useful for obtaining the amplitude of the blink events. Figure 6c–f illustrates the Max and Mix box plot for different eye blinks for both channels.

Time-domain features

In this step, we examined any specific characteristics or patterns (also called transient events) of the EEG signal in the time domain that occur with the eye blinking52. We analyzed the following parameters:

-

(a)

Kurtosis: This parameter assesses the sharpness of the EEG signal peaks due to the eye blinks. The box plot of the Kurtosis of eye blinks for both channels is shown in Fig. 7a,b. Eye blinks can generate sharp spikes on the EEG signal, and Kurtosis is the transient spikes in the EEG signal over the time domain.

-

(b)

Skewness: Eye blinks can be represented in positive or negative deflections in the time domain EEG signal. Skewness can measure these asymmetry characteristics for different eye blinks, which is shown in Fig. 7c,d.

-

(c)

Zero-Crossing Rate (ZCR): ZCR counts the frequency of the EEG signal crossing the zero-amplitude line within a time window. In the time domain, the eye blink signal repeatedly oscillates the zero amplitude, which may be an important parameter for detecting eye blinks. Figure 7e,f illustrate the Zero-Crossing Rate (ZCR) box plot for different eye blinks for both channels.

Amplitude-driven features

In this context, we focused on the signal’s magnitude and amplitude on different eye blinks for both channels 1 and 253. We analyzed the following parameters:

-

(a)

Peak-to-peak amplitude: This feature measures the maximum (peak) and minimum (trough) amplitudes of the EEG signal for different eye blinks. Different eye blinks (0b, 1b, 2b) generate different levels of amplitudes (shown in Fig. 5). For this reason, these features will be vital for classifying eye blink detection. Figure 8a,b show the box plot for Peak-to-Peak Amplitude for different eye blinks.

-

(b)

Mean absolute amplitude: This feature computes the average of the absolute values of the signal amplitudes over a time window. This will help to determine the overall magnitude of the signal for a specific eye blink. Figure 8c,d show the box plot for the Mean Absolute Amplitude for different eye blinks.

Frequency-domain features

In this step, we analyzed the power of EEG signals in specific frequency bands for different eye blinks, both channels one and two54. We evaluated the data across the subsequent band powers:

-

(a)

Delta band power: Eye blinks often produce low-frequency signals, and in this step, we analyze the EEG signal within the delta frequency range (0.5–4 Hz). Figure 9a,b illustrate the box plot for the Delta Band Power for different eye blinks.

-

(b)

Theta Band Power: Similar to Delta Band Power, in this step, we analyze the EEG signal within the theta frequency range (4–8 Hz). Figure 9c,d illustrate the box plot for the Theta Band Power for different eye blinks.

Step 4: Best feature selection: The box plots (Figs. 6, 7, 8 and 9) of the feature extraction steps show that any eye blink (1b or 2b) can easily be separated from no-eye blink EEG data. However, some of the box plots overlap for one and consecutive two-eye blinks. We need to select the most significant features from the Feature Extraction steps to train the classical machine learning model for accurately detecting eye blinks (0b, 1b, 2b). Based on the box plots and values of the extracted features, we selected the most important features for channel 1, channel 2, and channel 1&2 (Combined), which are shown in Table 2. This feature list will be used to train the classical machine learning algorithms in the next step.

Step 5: Train machine learning models: After selecting the important features, we implemented and ran three classical machine learning algorithms, including XGBoost, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Neural Network (NN) in Google Colab to detect eye blinks (0b, 1b, 2b) using the feature list. We have trained and evaluated the following machine learning algorithms separately for channel 1, channel 2, and channel 1&2 (combined). For every machine learning algorithm, we used 70% of the participants’ data for training, and 30% was used for testing. We trained the following machine-learning model:

-

(a)

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting): The XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) algorithm is a powerful and efficient machine learning technique based on decision tree ensembles17,18. We configured the model with multi-class logarithmic loss (mlogloss) as the evaluation metric and trained using gradient boosting to optimize classification performance. The model achieved an accuracy of 88.89% for classifying eye blinks using channel 1 and channel 2 data separately; however, its accuracy dropped by 56.0% when we used both channel 1 & 2 (combined data) for training. The detailed results of this algorithm are shown in Table 3.

-

(b)

Support Vector Machine (SVM): We also implemented the Support Vector Machine (SVM) model19 with the radial basis function (RBF) kernel to classify eye blinks into no blink (0b), single blink (1b), and two consecutive blinks (2b). The SVM architecture was configured with C = 1.0 for regularization and gamma=’scale’ to automatically compute the kernel coefficient. Missing data in the feature set was handled using mean imputation to ensure consistency across training and testing datasets. The model got the highest accuracy of 89.0% for channel 2 data, whereas its accuracy dropped by 78.0% and 56.0% for channel 1 and channel 1&2 (combined data), respectively.

-

(c)

Neural Network (NN): Lastly, we implemented a Neural Network (NN)20 to classify the eye blinks using a channel feature set. The NN architecture was designed with three layers: an input layer with dimensions matching the number of features, two hidden layers with 128 and 64 neurons, respectively, using the ReLU activation function, and an output layer with softmax activation to handle multi-class classification. The NN was trained by deploying the Adam optimizer and categorical cross-entropy loss for 20 epochs with a batch size of 32. Similar to the SVM model, we got the same accuracy for channel-wise, as shown in Table 3.

Step 6: Result analysis: The comparison results among the three machine learning models are summarized in Table 3. From Table 3, we can see that XGBoost, SVM, and Neural Network perform well on Channel 1, where XGBoost and Neural Network achieved the highest accuracy of 89%. However, the Neural Network’s performance dropped by 56.0% for channel 2. From these three classifiers, we observed that all performed badly on the combined channel 1&2 EEG data, and the accuracy was 56.0% for all three. This decline in accuracy highlights their inability to robustly handle overlapping or complex signals. Moreover, these models face challenges in differentiating between one blink (1b) and two consecutive blinks (2b) occurring within the same timeframe (as shown in Fig. 5), as evidenced by lower recall and F1 scores for 2b. These findings indicate that classical machine learning models fail to classify multiple blinks in real-time scenarios accurately. This underscores the necessity for deploying deep learning approaches like YOLO, which can capture temporal dependencies and complex patterns, where we need robust solutions for multiple eye blink detection by EEG-based BCI applications.

Deep learning models for eye blink detection

The Fig. 10 flowchart illustrates the stepwise methodology for classifying multiple eye blinks (0b, 1b, 2b) in one timeframe by deploying the YOLOv8 deep learning model. A detailed explanation of the steps is provided in the following:

Step 1: Data collection: We will use the same dataset (described in the “Eye blink artifacts (EBAs) removal”) that we used before for training classical machine learning.

Step 2: Preprocessing: We deploy a similar data cleaning approach as we did in the “Eye blink artifacts (EBAs) removal”. The only change we made was to obtain only the channel 1 EEG data for classifying the eye blinks, as channel 1’s EEG data showed better accuracy than classical machine learning. Additionally, we prepare channel 1’s EEG timeframe in such a way that more than one eye blinking event (0b, 1b, 2b) will exist in a single timeframe, like in Fig. 5.

Step 3: Convert EEG Data into segmented images: In this step, we converted each channel 1’s EEG raw data into image format; one of the images is shown in Fig. 11. These segmented images are essential as they serve as the input for the YOLOv8 model21,22, allowing it to detect the blink patterns by the visual representation. This step bridges the gap between time-series EEG data and image-based object detection, allowing the deep learning model to classify blink events with high accuracy and reliability.

Step 4: Annotate each image using bounding boxes: We make the following Algorithm 1, shown in Fig. 12, to annotate each image using bounding boxes and generate the bounding box values for an input image. Using Algorithm 1, we can get the following bounding box values for Fig. 11.

0 | 0.426042 | 0.485226 | 0.044611 | 0.661701 |

1 | 0.788868 | 0.500104 | 0.101111 | 0.706319 |

Step 5: Split images into training and validation sets: In this step, we split our images into training and validation sets to effectively train and test the model. Similar to “Eye blink artifacts (EBAs) removal”, we use 70% of the images to train the model, and the remaining 30% are used for validation. This split ensures that the model’s performance is tested on unseen data, accurately assessing its generalizability and robustness to new inputs.

Step 6: Train YOLOv8 model using ultralytics package: We used the Ultralytics package to train and fine-tune the YOLOv8 model to detect and classify the human eye blinks (0b, 1b, 2b) from the EEG-based annotated images. We ensure all of our training images have more than one eye.

blink (1b, 2b) so that the YOLOv8 model can train robustly and can leverage its state-of-the-art object detection architecture to learn the significant patterns and features associated with different blink events (0b, 1b, 2b). The training model showed strong performance metrics: a Box Precision (P) of 95.4%, a Box Recall (R) of 98.6%, mAP@50 of 99.5%, and mAP@50–95 of 65.3%, which the model’s high accuracy in detecting and classifying eye blinks, particularly at lower IoU thresholds (mAP@50), reflecting its capability to differentiate between blink events in the imaged segmented EEG data effectively. Figure 13 illustrates training and validation metrics for the trained YOLOv8 object detection model over 100 epochs.

Step 7: Test the final model: After training and validating the YOLOv8 model, in this step, we tested the trained model with unseen and unknown eye blink data to measure the model’s performance. In all five test cases (illustrated in Fig. 14a–e), the trained model successfully identified every eye blink, highlighting its reliability and exceptional accuracy for real-time integration into BCI applications.

Discussion

From the EEG signal analysis and result section, we can find the following findings:

-

Finding 1: The consecutive two-eye blinks EEG raw signals are different from single or no-eye blinks (shown in Fig. 5). This differentiation can be significant to build a novel BCI application through eye blink detection.

-

Finding 2: Previous research has already established that the human brain’s frontal lobe, particularly the prefrontal cortex, controls the eye blinks. For this reason, the Fp1 (channel 1) and Fp2 (channel 2) of the Ultracortex “Mark IV” 8-channel EEG headset23 can detect the brain activity that is responsible for eye blink detection.

-

Finding 3: The Fp1-channel 1 and Fp2-channel 2 can be used for EEG feature extraction and deploying the selected features for eye blink classification. Among these two channels, channel 1’s features are more significant in building a machine-learning model with higher accuracy, as shown in Table 3. However, the combined channel 1 and channel 2 EEG data show poorer performance by the machine learning models.

-

Finding 4: Classical machine learning (XGBoost, Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Neural Network (NN)) can classify the eye blinks (0b, 1b, 2b), but they are not suitable to apply for real-time BCI application, where more than one eye blinks (0b, 1b, 2b) will appear in a single frame.

-

Finding 5: Deep learning algorithms such as the YOLOv8 model are a potential candidate to detect more than one eye blink in a single time frame, shown in Fig. 13, which is essential for any real-time BCI application.

Impact and challenges

Our pre-trained YOLOv8 can be applied to build any BCI application, which classifies eye blinks from EEG-annotated images. A system architecture has been demonstrated in Fig. 15. We can deploy the proposed architecture for different potential use cases:

-

Assistive technologies for people with disabilities—where individuals with motor impairments can communicate by eye blinking based on the context. The blink patterns (0b, 1b, 2b) can be translated into actions or text on a screen.

-

Augmented and virtual reality interfaces—where eye blinks can be used for input in VR/AR environments to select menu options or navigate interfaces through blink patterns.

-

Human–computer interaction (HCI)—where any type of hand/speech-free communication can be enabled through the proposed architecture (shown in Fig. 14).

-

Neuroscience research and cognitive monitoring—where research can correlate blink patterns and cognitive states such as attention, concentration, or emotional state during experiments.

Challenges

Data acquisition was the biggest challenge we faced in the study. We need a noise-free environment to collect the EEG data. In this study, our expert team utilized a noise-controlled, facilitated environment that helped us collect noise-free and error-free EEG data. In the future, we plan to integrate a noise-canceling filter into the model, specifically tailored for eye blink detection, which can make the YOLOv8 model more robust for a wide range of applications.

Applications

While EEG-based eye blink detection is traditionally used to remove artefacts, our proposed and developed methodology will reposition them as intentional control signals for real-time brain–computer interface (BCI) applications. Specifically, this work can process and detect multiple eye blinks (no blink, single blink, and double blink), which can be a potential application in assistive technologies for individuals with motor impairments, allowing hands-free communication through blink-based commands. This study can be useful for integration into VR/AR environments, human-computer interaction (HCI) systems, and cognitive monitoring in neuroscience research.

Conclusion

In this study, we have successfully addressed a novel problem to classify human eye blinks (0b, 1b, 2b) from EEG signals. To solve this problem, we collected the EEG data (885,600 EEG data points) from 10 healthy participants under the approval IRB (Protocol #HR-4640) from XXX University, USA. We implemented both classical and deep machine learning approaches, evaluating their respective results, strengths, and limitations. After building all the machine-learning algorithms, we can conclude that the YOLOv8 model demonstrates robust model performance from EEG-annotated images, achieving high precision (95.4%), recall (98.6%), and mAP@50 (99.5%), indicating the model’s ability to detect and classify blink events accurately. We have also proposed an eye-blink-based BCI application by integrating our trained YOLOv8’s state-of-the-art object detection architecture with EEG data for real-time, non-invasive monitoring of human behavior. This novel approach can also pave the way for advanced applications in neuroscience, cognitive monitoring, and human-computer interaction.

Data availability

The datasets used in the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dennis, J., McFarland & Wolpaw, J. R. EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 4(December 2017), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COBME.2017.11.004 (2017).

Jonathan, R. et al. Brain–computer interfaces for communication and control. Clin. Neurophysiol. 113(6), 767–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1388-2457(02)00057-3 (2002).

2021. What is EEG (Electroencephalography) and How Does it Work?—iMotions. Retrieved January 5. https://imotions.com/blog/learning/research-fundamentals/what-is-eeg/#:~:text=EEG%20Frequency%20ranges%20/%20Frequency%20Bands%20*,Gamma%20Waves%20(%3E30%20Hz%2C%20typically%2040%20Hz) (2025).

Jacques, J. & Vidal Toward direct brain–computer communication. 2(1), 157–180. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.BB.02.060173.001105 (1973).

Andreas, A. & Ioannides and Fahmeed Hyder. Magnetoencephalography (MEG). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59745-543-5_8 (Humana Press, 2009).

Daniel, L., Keene, S., Whiting, Enrique, C. G. & Ventureyra Electrocorticography. (2000). https://doi.org/10.1684/j.1950-6945.2000.tb00352.x

Edgar, A. D., et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI) of the human brain. J. Neurosci. Methods. 54(2), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0270(94)90191-0 (1994).

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy. IEEE J. Mag. 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1109/MEMB.2006.1657788 (2006).

Won-Du Chang, H. S., Cha, K., Kim & Chang-Hwan Im Detection of eye blink artifacts from single prefrontal channel electroencephalogram. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 124, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CMPB.2015.10.011 (2016).

Ajay Kumar Maddirala and & Veluvolu, K. C. Eye-blink artifact removal from single channel EEG with k-means and SSA. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 11043. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-021-90437-7 (2021).

Giudice, M. L. et al. Visual explanations of deep convolutional neural network for eye blinks detection in eeg-based bci applications. In 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 01–08. https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN55064.2022.9892567 (IEEE, 2022).

Liu, J., Wu, X., Zhang, L. & Zhou, B. A hybrid brain–computer interface system based on motor imageries and Eye-blinking. In Advances in Brain Inspired Cognitive Systems: 9th International Conference, BICS 2018, Xi’an, China, July 7–8, 2018, Proceedings, vol. 9, 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00563-4_20 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

Derchi, C. C. et al. Distinguishing intentional from nonintentional actions through Eeg and kinematic markers. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 8496. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34604-y (2023).

Rihana, S., Damien, P. & Moujaess, T. Efficient eye blink detection system using RBF classifier. In 2012 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), 360–363. https://doi.org/10.1109/BioCAS.2012.6418422/ (IEEE, 2012).

de López, R., Jiménez Naharro, R. & Gómez Bravo, F. A Hardware-based configurable algorithm for eye Blink signal detection using a single-channel BCI headset. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23115339/.

Ranjan, R. et al. Real time eye blink extraction circuit design from EEG signal for ALS patients. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 38, 933–942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-017-0357-7 (2018).

Tiwari, A. & Chaturvedi, A. A multi-class EEG signal classification model using spatial feature extraction and XGBoost algorithm. In 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 4169–4175. https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS40897.2019.8967868 (IEEE, 2019).

XGBoost for Gradient Boosted Trees. Retrieved January 5. (2025). https://docs.coiled.io/user_guide/xgboost.html

Agrawal, R. & Bajaj, P. EEG based brain state classification technique using support vector machine-a design approach. In 2020 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Sustainable Systems (ICISS), 895–900. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICISS49785.2020.9316073 (IEEE, 2020).

Hazrati, M. K. & Erfanian, A. An online EEG-based brain–computer interface for controlling hand Grasp using an adaptive probabilistic neural network. Med. Eng. Phys. 32 (7), 730–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2010.04.016 (2010).

Xu, D., et al. A brain-computer interface based semi-autonomous robotic system. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), 1083–1086. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROBIO54168.2021.9739367 (IEEE, 2021).

Ultralytics, Y. O. L. O. & Retrieved January 5. https://docs.ultralytics.com/ (2025).

Ultracortex. Mark IV EEG Headset. Retrieved March 17. https://shop.openbci.com/products/ultracortex-mark-iv (2024).

Shahbakhti, M. et al. Fusion of EEG and eye Blink analysis for detection of driver fatigue. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 31, 2037–2046. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2023.3267114 (2023).

Madile, T. T., Hlomani, H. B. & Zlotnikova, I. Electroencephalography biometric authentication using eye Blink artifacts. Indonesian J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 36(2). https://doi.org/10.11591/ijeecs.v36.i2.pp872-881

Zhang, Y., Zheng, X., Xu, W. & Liu, H. Rt-blink: A method toward real-time blink detection from single frontal Eeg signal. IEEE Sens. J. 23 (3), 2794–2802. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2022.3232176 (2023).

Salinas, R., Schachter, E. & Miranda, M. Recognition and real-time detection of blinking eyes on electroencephalographic signals using wavelet transform. In Progress in Pattern Recognition, Image Analysis, Computer Vision, and Applications: 17th Iberoamerican Congress, CIARP 2012, Buenos Aires, Argentina, September 3–6, 2012. Proceedings, vol. 17, 682–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-33275-3_84/ (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012).

Giudice, M. L. et al. 1D Convolutional neural network approach to classify voluntary eye blinks in EEG signals for BCI applications. In 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN48605.2020.9207195 (IEEE, 2020).

Wahab, M. A. & Mansor, W. Analysis of EEG signal obtained during actual and imagined eye blinking. In 2018 IEEE-EMBS Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Sciences (IECBES), 270–273. https://doi.org/10.1109/IECBES.2018.8626641/ (IEEE, 2018).

Kaneko, K. & Sakamoto, K. Evaluation of three types of blinks with the use of electro-oculogram and electromyogram. Percept. Mot. Skills. 88 (3), 1037–1052. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1999.88.3.1037 (1999).

Agostino, R. et al. Voluntary, spontaneous, and reflex blinking in parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 23 (5), 669–675. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21887 (2008).

Kaneko, K., Mito, K., Makabe, H., Takanokura, M. & Sakamoto, K. Cortical potentials associated with voluntary, reflex, and spontaneous blinks as bilateral simultaneous eyelid movement. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 44 (8), 455–462 (2004).

Nguyen, T., Nguyen, T. H., Truong, K. Q. D. & Van Vo, T. A mean threshold algorithm for human eye blinking detection using EEG. In 4th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering in Vietnam, 275–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-32183-2_69 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013).

Tibdewal, M. N., Fate, R. R., Mahadevappa, M. & Ray, A. Detection and classification of eye blink artifact in electroencephalogram through discrete wavelet transform and neural network. In 2015 International Conference on Pervasive Computing (ICPC), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/PERVASIVE.2015.7087077 (IEEE, 2015).

Kanoga, S. & Mitsukura, Y. ICA-based positive semidefinite matrix templates for eye-blink artifact removal from EEG signal with single-electrode. In 2015 10th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ASCC.2015.7244386 (IEEE, 2015).

Kleifges, K., Bigdely-Shamlo, N., Kerick, S. E. & Robbins, K. A. BLINKER: automated extraction of ocular indices from EEG enabling large-scale analysis. Front. NeuroSci. 11, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2017.00012 (2017).

Tran, D. K., Nguyen, T. H. & Ngo, B. V. Amplitude Thresholding of EEG Signals For Eye Blink and Saccade Detection. In 2021 International Conference on System Science and Engineering (ICSSE), 268–273. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSSE52999.2021.9538428 (IEEE, 2021).

Kong, W. et al. Automatic and direct identification of Blink components from scalp EEG. Sensors. 13 (8), 10783–10801. https://doi.org/10.3390/s130810783 (2013).

Rao, G. B. N., Anumala, V. S., Pani, P. P. & Sidhireddy, A. Automatic detection and correction of Blink artifacts in single channel EEG signals. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.14569/ijacsa.2020.0110144 (2020).

Sammaiah, A., Narsimha, B., Suresh, E. & Reddy, M. S. On the performance of wavelet transform improving Eye blink detections for BCI. In 2011 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Electrical and Computer Technology, 800–804. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICETECT.2011.5760228 (IEEE, 2011).

Jefri, L. A. M., Rahman, F. A., Malik, N. A. & Isa, F. N. M. Eye Blink identification and removal from single-channel EEG using EMD with energy threshold and adaptive filter. IIUM Eng. J. 24 (2), 141–158. https://doi.org/10.31436/iiumej.v24i2.2814 (2023).

Gupta, S. S. et al. Detecting eye movements in EEG for controlling devices. In 2012 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Cybernetics (CyberneticsCom), 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1109/CyberneticsCom.2012.6381619 (IEEE, 2012).

Ghosh, R., Sinha, N. & Biswas, S. Automated eye Blink artifact removal from EEG using support vector machine and autoencoder. IET Signal. Process. 13, 1–7 (2019).

Ferrari Iaquinta, A., de Sousa Silva, A. C., Ferraz, A. Júnior, de Toledo, J. M. & Voltani von Atzingen, G. EEG multipurpose eye Blink detector using convolutional neural network. ArXiv e-prints. arXiv-2107. https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v10i15.22712 (2021).

Matiko, J. W., Beeby, S. & Tudor, J. Real time eye blink noise removal from EEG signals using morphological component analysis. In 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2013.6609425 (IEEE, 2013).

Dehzangi, O., Melville, A. & Taherisadr, M. Automatic eeg blink detection using dynamic time warping score clustering. In Advances in Body Area Networks I: Post-Conference Proceedings of BodyNets 2017, 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02819-0_5 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Farago, E., Law, A. J., Hajra, S. G. & Chan, A. D. Blink and saccade detection from forehead EEG. In 2022 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/I2MTC48687.2022.9806494 (IEEE, 2022).

UBICOMP Research Lab. https://ubicomp.cs.mu.edu/index.html (accessed 09 Apr 2025).

Abi-Jaoude, E., Segura, B., Cho, S. S., Crawley, A. & Sandor, P. The neural correlates of self-regulatory fatigability during inhibitory control of eye blinking. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 30 (4), 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17070140 (2018).

Pouget, P. The cortex is in overall control of ‘voluntary’eye movement. Eye. 29 (2), 241–245. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2014.284 (2015).

Acharya, U. R., Sree, S. V., Swapna, G., Martis, R. J. & Suri, J. S. Automated EEG analysis of epilepsy: a review. Knowl. Based Syst. 45, 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2013.02.014 (2013).

Hjorth, B. EEG analysis based on time domain properties. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 29 (3), 306–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(70)90143-4 (1970).

Subasi, A. & Ercelebi, E. Classification of EEG signals using neural network and logistic regression. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 78 (2), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2004.10.009 (2005).

Dressler, O., Schneider, G., Stockmanns, G. & Kochs, E. F. Awareness and the EEG power spectrum: analysis of frequencies. Br. J. Anaesth. 93 (6), 806–809. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeh270 (2004).

Acknowledgements

Grants from the Ubicomp Lab, Department of Computer Science, Marquette University partially support this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R. developed the algorithm, designed the hardware system, collected the data, and performed data analysis. N.U.S.S. surveyed the literature, generated figures and tables, reviewed and proofread the article. I.I. and A.P. helped in data collection. R.A.K. and F.A. provided the medical science expertise, and validated the data. S.M.M. co-designed the hardware system and reviewed the article. S.I.A. came up with the idea and led the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rabbani, M., Sabith, N.U.S., Parida, A. et al. EEG based real time classification of consecutive two eye blinks for brain computer interface applications. Sci Rep 15, 21007 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07205-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07205-0