Abstract

This study proposes a novel “B” coefficient to quantitatively assess the uniformity of airflow fields in coal mine heading faces equipped with the long-pressure and short-suction dust control system. The research systematically investigates the relationship between the radial-to-axial airflow ratio, the proposed uniformity coefficient, and dust suppression efficiency. The results demonstrate that increasing the radial-to-axial airflow ratio from 0.5 to 1.5 leads to a gradual reduction in airflow field uniformity while significantly enhancing dust removal performance. Specifically, the dust removal efficiency improves by 37.7% at the driver’s operating position and by 27.7% at a location 5 m behind the driver. The study reveals a distinct nonlinear relationship between the “B” coefficient and dust control effectiveness, highlighting the critical role of airflow field optimization in dust suppression. These findings validate the practical applicability of the “B” coefficient as an evaluation metric for airflow regulation in long-pressure and short-suction systems. The proposed method offers a scientifically grounded approach for assessing and improving dust control strategies in coal mining operations, addressing a longstanding gap in quantitative airflow field analysis for heading face ventilation systems. The research outcomes provide valuable theoretical guidance and technical references for optimizing dust control parameters in similar mining environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

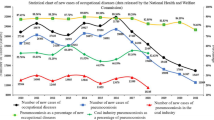

Coal mining remains a vital global industry, providing significant support to the world’s energy supply. However, the high concentration of dust in coal mines poses a serious threat to miners’ health. The fully mechanized heading face is one of the most dust-polluted areas in underground coal mines, and prolonged exposure to this environment can lead to severe respiratory diseases, with coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP) being one of the most prevalent and devastating conditions1. With the “Healthy China” strategy elevated to a national priority, the health impacts of coal mine dust exposure have garnered increasing attention2. As of 2023, the cumulative number of occupational pneumoconiosis cases in China has exceeded 930,000, with coal workers’ pneumoconiosis and silicosis being the most common, primarily concentrated in industries such as coal mining, metal mining, and building materials production3. Pneumoconiosis not only severely affects patients’ quality of life but also places a heavy economic burden on healthcare systems and mining companies4,5.

To mitigate the risks associated with high dust concentrations, various dust suppression technologies have been applied in fully mechanized heading faces, including spray dust suppression, foam dust suppression, and long-pressure and short-suction ventilation dust removal. Among these, the long-pressure and short-suction ventilation dust removal technology has been widely adopted due to its high efficiency6,7. By controlling airflow, capturing, and removing dust particles from the working environment, this technology reduces overall dust concentrations and minimizes miners’ exposure to dust. Despite the positive outcomes of these measures, challenges remain in achieving optimal dust control. Factors such as dust particle size, the dynamic nature of tunneling operations, and variations in environmental conditions can all influence the overall effectiveness of dust removal systems8,9,10. In light of these challenges, this study aims to explore and evaluate the effectiveness of current dust prevention technologies, particularly the application of the long-pressure and short-suction technique. By analyzing the operational parameters, environmental conditions, and health impacts of these technologies, the study seeks to provide a scientific basis for developing more efficient and reliable dust control strategies. Ultimately, the research aligns with the overarching goals of the “Healthy China” initiative, aiming to safeguard miners’ health and safety and reduce the incidence of occupational respiratory diseases.

Engineering experience has shown that the efficiency of the long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system is primarily influenced by factors such as dust source characteristics, the matching of airflow rates for pressurization, extraction, and airflow control, and the distance between the dust extraction port and the dust source. Zheng et al.11 used numerical simulations and field measurements to obtain the dust distribution characteristics under long-pressure and short-suction ventilation in fully mechanized heading faces, finding that dust concentrations decrease continuously along the tunnel and stabilize after 20 m from the working face. Jiang et al.12 conducted similar simulation experiments on a long-pressure and short-suction ventilation dust removal platform, testing the impact of different dust source movement paths on dust distribution. The results showed that under lateral dust movement paths, the hazards to driver and pedestrians were reduced. Xu et al.13 designed a dual air curtain device based on the traditional long-pressure and short-suction ventilation system, which transforms the pressurized airflow into two air curtains using a wind box and deflector plates, improving the dust removal rate in the breathing zone. Nie et al.14 used FLUENT software to simulate the effects of different dust extraction positions and extraction airflow rates on dust diffusion. The results indicated that the minimum dust pollution occurred when the dust extraction port was located on the opposite side of the pressurized air duct and the minimum extraction airflow rate was 330 m³/min. Zhang et al.15 found through numerical simulations and similar experiments that the dust removal efficiency was highest when the dust extraction port was 1 m from the working face. Wang et al.16 used numerical simulations to study the effect of the pressurization-to-extraction airflow ratio on the dust suppression efficiency of air curtains, finding that when the ratio was 0.8, the dust concentration at the tunneling driver’s position was reduced by approximately 50%. Gong et al.17,18 established an airflow control model using a BP neural network algorithm, with gas concentration, dust concentration, and wind speed as input layers, optimizing airflow distribution by adjusting the angle of the pressurized air duct outlet to reduce gas and dust concentrations. Kurnia et al.19 studied dust diffusion behavior under six ventilation methods, including blowing fan, exhaust fan, brattice, and combinations thereof, finding that using a brattice provided better dust control. Wang et al.20 investigated the impact of ventilation parameters on dust particles in the respiratory risk zone of tunnels through experiments and numerical simulations, establishing a random forest prediction model where the importance of influencing factors was ranked as follows: distance from the pressurized air outlet to the dust source, airflow velocity, pressurization-to-extraction airflow ratio, and dust emission time. J. Toraño et al.21 used one-way coupling simulations and field measurements to study the effects of different heights of the dust extraction duct on tunnel airflow behavior while keeping the pressurized air duct position constant. Cai et al.22 set the pressurization airflow rate in a hybrid ventilation system to 500 m³/min and achieved optimal working conditions by varying the dust extraction airflow rate, studying the impact of the pressurized air duct height on dust suppression performance. The results showed that a dust extraction airflow rate of 550 m³/min and a duct height of 2 m provided the best dust suppression combination. Li et al.23 studied the effect of different axial-to-radial airflow ratios in wall-mounted air ducts on dust control efficiency, finding that a ratio of 2:8 resulted in a dust concentration of 57 mg/m³ at the driver’s position.

Currently, the effectiveness of the long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system is typically evaluated based on dust migration and distribution24,25,26. Dust concentrations at different locations, such as the driver’s position, 5 m behind the operator, and behind the dust removal fan, are measured to reflect the extent of dust pollution in the fully mechanized heading face, thereby determining the optimal airflow control parameters. In the long-pressure and short-suction system, airflow control devices such as wall-mounted air ducts27,28,29 play a crucial role in altering the airflow distribution in the working face space, preventing dust diffusion and improving the dust collection efficiency of the dust removal system. The axial-to-radial airflow ratio and outlet distance30, as well as structural parameters31 of the wall-mounted air duct, significantly affect the airflow field. However, the distribution state of the airflow field has not received much attention, and the relationship between the airflow field and airflow control effectiveness has not been reported. The traditional dust concentration evaluation method only reflects the dust concentration at a limited number of points or local spaces, which is easily affected by location selection deviation and cannot intervene in dust diffusion in advance.

Therefore, this study aims to establish an evaluation index for the airflow control effectiveness of the long-pressure and short-suction system, quantitatively assessing the airflow distribution characteristics in the fully mechanized heading face space. This index will be used to evaluate the effectiveness of different airflow control parameters, filling the gap in airflow field evaluation methods for dust control in fully mechanized heading faces and guiding the application of long-pressure and short-suction airflow control and dust removal systems.

Construction of airflow control effectiveness evaluation method

Mechanism of airflow control and dust suppression in the long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system

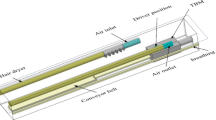

The “long-pressure” component of the long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system typically consists of an auxiliary fan, a positive pressure air supply duct, and an airflow control device installed at the end of the positive pressure air supply duct. The “short-suction” component usually includes a dust collector, a negative pressure dust extraction duct, and a dust collection hood. A typical layout of the long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system is shown in Fig. 1.

The mechanism of airflow control and dust reduction in the long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system is as follows: the airflow control device converts part of the axial airflow into a uniform air curtain that advances along the entire tunnel cross-section toward the working face, creating an air screen in front of the driver to prevent dust generated during tunneling from diffusing backward. The dust-laden airflow is then captured by the dust collection hood and purified by the dust collector. The rationality of the airflow field regulation in the air supply system is a key factor influencing the dust reduction efficiency of the long-pressure and short-suction system. Without airflow control measures, the air supply duct blows directly toward the working face, and the dust generated during coal cutting to rapidly diffuse under the disturbance of the high-speed airflow, making it difficult for the dust collection hood to capture the dust. By adding an airflow control device such as a wall-mounted air duct at the end of the “long-pressure” air supply duct, part of the axial airflow blowing directly toward the working face is diverted radially, confining the dust-laden airflow to a certain area near the working face and preventing uncontrolled dust diffusion. This provides the necessary time and space for the dust collector to capture and purify the dust. The working principle is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Hypothesis of optimal dust control airflow field and airflow field uniformity coefficient

Based on the analysis of the airflow control and dust reduction mechanism in the long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system, the primary function of airflow control is to convert part of the axial airflow blowing directly toward the working face into a uniform air curtain advancing along the entire tunnel cross-section. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the more uniform the airflow field in the tunnel, the less likely it is to form turbulent flow, which is more conducive to forming a forward-pushing air curtain. Conversely, an uneven airflow field, especially one that forms a distinct pressurized airflow jet impacting the dust-producing area of the working face, is more likely to cause dust escape and diffusion, making it less favorable for dust capture and purification. To evaluate the uniformity of the airflow field in the tunnel, this study introduces the airflow field uniformity coefficient as a quantitative measure. Compared to traditional dust concentration evaluation methods, the advantage of using flow field uniformity evaluation is that firstly, while traditional methods measure dust concentration at specific points, flow field uniformity evaluates the spatial uniformity of the entire airflow field, which proactively prevents dust diffusion rather than just measuring its result. Secondly, flow field uniformity directly links airflow distribution characteristics to dust control performance, whereas concentration metrics only reflect the outcome. Thirdly, the uniformity of the flow field can be changed by adjusting the air control parameters before dust escape.

Based on the above analysis, the airflow field uniformity coefficient ε for the tunnel cross-section is proposed. The calculation method for ε is as follows: the tunnel cross-section is evenly divided into j small sections, with a measurement point placed at the center of each section, as shown in Fig. 3. The standard deviation of the air velocity at the j measurement points is taken as the airflow field uniformity coefficient ε for that cross-section. To more accurately reflect the variation pattern of the airflow field in the tunnel, j is set to 16. The selection of 16 measurement points per cross-section balances accuracy and practicality. A higher number of points captures spatial variations in airflow more reliably. Preliminary tests indicate that fewer points can lead to inaccurate test results. While more points (e.g., 25) might marginally improve precision, the marginal gain diminishes beyond 16 points, and field measurements become impractical due to time constraints. Selecting 16 measurement points can basically reflect the flow field characteristics of the cross-section.

The air velocity at each measurement point should consider both the magnitude and the direction of the airflow. A coordinate system is established with the tunnel cross-section as the xy plane, the tunneling direction as the z-axis (positive in the tunneling direction and negative in the opposite direction), and the air velocity at each measurement point is converted based on the airflow direction, as shown in Fig. 4. The angle between vj and the z-axis is α.

The calculation method for the airflow field uniformity coefficient ε is as follows:

where ε is the airflow field uniformity coefficient; j is the jth measurement point; vj is the air velocity at the jth measurement point; α is the angle between vj and the z-axis; and \(\overline v\) is the average air velocity.

The calculation method for \(\overline v\) is as follows: the air velocities at the j measurement points are projected onto the z-axis direction, yielding the velocity of each point in the z-axis direction, vjcosα. The sum of all vjcosα values is divided by the number of measurement points j to obtain the average velocity \(\overline v\) :

Numerical simulation experiment design for airflow field uniformity coefficient in long-pressure and short-suction system

The calculation method for the airflow field uniformity coefficient in the tunnel has been proposed and constructed, but the rationality of the selected cross-section position and the evaluation method for the airflow field uniformity coefficient have not yet been verified. Therefore, numerical simulations were used to analyze the airflow field uniformity coefficient.

Geometric model setup

Based on the actual working conditions of the 2302 return airway heading face in Xiaoyun Coal Mine, Shandong Province, a numerical simulation experiment model was designed. The tunnel width is 4.2 m, the height is 3.6 m, the air supply flow rate at the working face is 400 m³/min, and the actual suction flow rate of the dust collector is approximately 350 m³/min. The distance between the dust extraction port and the working face is 4 m. A wall-mounted air duct is used for dust control, with a distance of 20 m from the air duct to the working face. Based on these parameters and the dimensions of the fully mechanized heading face equipment, a 1:1 geometric model of the long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system was established, as shown in Fig. 5. The geometric model was meshed using hexahedral and tetrahedral elements. For the small surface area of the radial outlet of the wall-mounted air duct, the mesh was divided into 5 cm units to ensure precision. For other entities and airflow field spaces, the mesh was divided into 40 cm, 20 cm, and 10 cm units, resulting in the mesh model shown in Fig. 6. A mesh independence test was conducted, and the calculated air velocities were consistent with relative errors 4.1% under 20 cm and 10 cm mesh conditions, so the 20 cm mesh unit was selected.

Boundary conditions and dust characteristics setup

The simulations were performed using ANSYS Fluent 17.0. The standard k-ε model was chosen. A pressure based solver using SIMPLE algorithm and second-order discretization of momentum and turbulence equations. For the boundary condition setup, the inlet of the air supply duct was set as a velocity inlet, and the inlet air velocity was calculated based on the air supply flow rate. Calculated by pressing the air volume of 400m3/min, the inlet velocity is 13.3 m/s, and the turbulence intensity is 2.3%. The radial outlet of the wall-mounted air duct was set as a fan, and the ratio of radial to axial airflow was adjusted by the negative pressure. The inlet of the dust collector was set as a fan, and the dust extraction flow rate was adjusted by the negative pressure. The ends of the air ducts and the outlet of the dust collector were set as internal boundaries, serving as the contact surfaces between two airflow field regions. The working face, roof, floor, and sidewalls of the tunnel were set as walls, and the tunnel outlet was set as a free outlet. The surfaces of entities within the airflow field were also set as walls.

The working face cross-section was set as the dust emission source. Based on the measured dust concentration at the working face and the particle size analysis of dust samples, the dust emission intensity was set to 5 g/s, with a minimum particle size of 1 μm, a maximum particle size of 100 μm, a median particle size of 20 μm, and a dispersion coefficient of 1.5. After setting the parameters, the simulation was solved using a pressure-based solver and the standard k-ε turbulence model.

Radial-to-axial airflow ratio setup

The airflow rate blowing directly toward the working face from the air supply duct is denoted as Q1, and the airflow rate from the radial outlet of the wall-mounted air duct is denoted as Q2. The ratio of the radial airflow rate to the axial airflow rate (Q2/Q1) is denoted as η, referred to as the “radial-to-axial airflow ratio.” Laboratory tests and on-site engineering applications have shown that when the ratio is less than 0.5, the strength of the dust control air curtain is insufficient and the dust control effect is not good. When the ratio is greater than 1.5, the effect of dust control improvement is not significant. Numerical simulations of the airflow field and dust migration patterns in the tunnel were conducted for η values of 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, and 1.5.

Analysis of airflow field experiment results

Distribution characteristics of airflow field in different regions

The airflow field distribution in the tunnel was obtained through numerical simulations for five different η values. Although the airflow field at the working face varied with different η values, the overall characteristics were consistent. The airflow field along the tunnel can be divided into three regions: the horizontal vortex region near the working face, the radial vortex region in the dust control section, and the backflow region behind the dust collector. The distribution of these three regions is shown in Fig. 7.

(1) Horizontal Vortex Region Near the Working Face.

The horizontal vortex region near the working face is generally located within 5–10 m of the working face, as shown in Fig. 8. In this region, the airflow from the air supply duct blowing directly toward the working face (Q1) and the airflow from the wall-mounted air duct (Q2) form a horizontal vortex. The distribution characteristics of the horizontal vortex are significantly influenced by Q1. The higher the Q1, the higher the outlet wind speed, resulting in a higher vortex velocity and a more chaotic vortex flow field. Based on the vortex distribution range, when η is 0.5, the vortex is mainly concentrated within 5 m of the working face. As η increases, the vortex range gradually expands, reaching 10 m when η is 1.5.

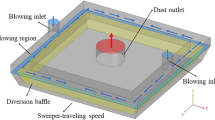

(2) Radial Vortex Region in the Dust Control Section.

The radial vortex region in the dust control section is located at the position of the wall-mounted air duct, as shown in Fig. 9. After the radial airflow exits the wall-mounted air duct, part of it forms a vortex air curtain along the radial direction, while the other part is deflected horizontally by the tunnel walls, flowing toward the working face and the tunnel exit. The intensity of the radial vortex region increases with η. When η is 0.5, the average wind speed at the radial outlet is approximately 7 m/s, while when η is 1.5, the average wind speed increases to approximately 15 m/s. The increase in wind speed also leads to more significant deflection and splitting of the airflow after being blocked by the tunnel walls, resulting in a stronger airflow circulation. This intensified airflow circulation helps further dilute and remove dust from the tunnel, thereby enhancing dust control effectiveness.

(3) Backflow Region Behind the Dust Collector.

The backflow region behind the dust collector is located behind the dust collector installation position and extends to the tunnel exit, as shown in Fig. 10. The airflow characteristics in this region are primarily influenced by the negative pressure effect generated by the dust collector’s suction inlet, creating a relatively stable backflow zone behind the dust collector. The intensity of the backflow region is closely related to the dust collector’s suction flow rate and the tunnel cross-section. With a suction flow rate of 350 m³/min and a tunnel cross-sectional area of 15.1 m², the high air velocity at the dust collector outlet mainly affects the area within 10 m behind the outlet, resulting in an uneven airflow distribution with high air velocity in the center and low air velocity at the periphery.

Selection of tunnel cross-section for airflow field evaluation and calculation method for airflow field uniformity coefficient

Based on the analysis of the airflow field distribution characteristics in different regions along the tunnel, it is evident that the airflow field varies significantly with distance from the working face. Therefore, evaluating the airflow control effectiveness based on the airflow field uniformity coefficient at a single cross-section may lead to uncertainty. To more accurately evaluate the uniformity of the airflow field at the working face, the airflow field uniformity coefficients at multiple cross-sections are weighted and averaged to offset the random errors of individual cross-sections. The mean square error was selected for the uniformity coefficient B because it effectively quantifies the dispersion of airflow velocity deviations across the tunnel cross-section, penalizing larger deviations more heavily than smaller ones such as mean absolute error.

Since the goal of airflow control is to confine dust to the area in front of the driver, the driver’s position is selected as the starting point. The dust collector is typically installed 25–40 m behind the operator, so the farthest cross-section is selected at 45 m behind the driver. Based on the stability of the airflow field, seven cross-sections are selected to calculate the overall airflow field uniformity coefficient B: at the driver’s position, 5 m behind the driver, 10 m behind the driver, 15 m behind the driver, 25 m behind the driver, 35 m behind the driver, and 45 m behind the driver. Since higher air velocities have a greater impact on the uniformity of the airflow field, the weight for each cross-section is determined by the ratio of the average air velocity at that cross-section to the total average air velocity across all cross-sections. The calculation method for the overall airflow field uniformity coefficient B is shown in Eq. (3).

where B is the overall airflow field uniformity coefficient; i is the cross-section number, i = 1–7; εi is the airflow field uniformity coefficient at the ith cross-section; and \(\overline v_{i}\) is the average air velocity at the ith cross-section.

Verification of airflow field evaluation results

To verify the feasibility of using the airflow field uniformity coefficient B to evaluate airflow control effectiveness, a comparison was made with the dust concentration at the working face. Since dust measurement points at the tunneling face are typically located at the driver’s position and 5 m behind the driver, the dust concentrations at these positions were used for comparison. By adjusting the axial and radial outlet sizes of the air control device to change the air volume, the air volume is monitored by air volume sensors at both ends. The relationship between the total dust removal efficiency E and the airflow field uniformity coefficient B under different η values is shown in Fig. 11.

As shown in Fig. 11, as the radial-to-axial airflow ratio η increases, the dust removal efficiency E at the driver’s position and 5 m behind the driver improves to varying degrees. The dust removal efficiency at 5 m behind the driver is consistently slightly better than that at the driver’s position. When η increases from 0.5 to 1.5, the dust removal efficiency at the driver’s position improves by 37.7%, and the efficiency at 5 m behind the driver improves by 27.7%. The airflow field uniformity coefficient B gradually decreases as η increases, showing an opposite trend to the dust removal efficiency curve. The decrease in B is more pronounced when η increases from 0.5 to 1.0, and the rate of decrease slows when η increases from 1.0 to 1.5. A logistic function was established between the average dust removal efficiency E and the airflow field uniformity coefficient B with correlation coefficient 98.2%, as shown in Fig. 12, confirming the feasibility of using the airflow field uniformity coefficient to evaluate airflow control and dust removal effectiveness.

Conclusions

(1) Based on the analysis of the airflow control and dust reduction mechanism in the long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system, the hypothesis of an optimal dust control airflow field was proposed, and the airflow field uniformity coefficient B was introduced to evaluate the uniformity of the airflow field in the tunnel. Numerical simulation results show that the overall airflow field uniformity coefficient B can effectively reflect the uniformity of the airflow field in the tunnel and exhibits a strong negative correlation with dust concentration at the working face. As the radial-to-axial airflow ratio η increases, the airflow field uniformity coefficient B gradually decreases, while the dust concentration at the working face significantly decreases, demonstrating the feasibility and effectiveness of this coefficient in evaluating the airflow control effectiveness of the long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system.

(2) By comparing the airflow field and dust concentration at the working face under different radial-to-axial airflow ratios, the rationality of the airflow field uniformity coefficient B was verified. The results show that the radial-to-axial airflow ratio η has a significant impact on airflow field uniformity and dust control effectiveness, and the airflow field uniformity coefficient B can effectively reflect the airflow control effectiveness. This method provides a scientific basis for evaluating the effectiveness of the long-pressure and short-suction ventilation and dust removal system in tunneling faces.

(3) This study focused on the impact of the radial-to-axial airflow ratio on airflow field uniformity and dust control effectiveness. However, in practical engineering, dust removal effectiveness is also influenced by the coupling effects of other factors, such as the structural parameters of the wall-mounted air duct, the physical and chemical properties of dust, and the shape and size of the tunnel. Future research could consider multiple factors to establish a more comprehensive airflow control evaluation method, enabling more accurate prediction and optimization of dust removal effectiveness.

Data availability

Data is provided within the supplementary information files.

References

Devnath, L. et al. Computer-aided diagnosis of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis in chest X-ray radiographs using machine learning: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (11), 6439 (2022).

Xinyue, C. H. A. N. G. et al. Pneumoconiosis mortality and its trends among urban and rural residents, 2002–2021. Mod. Prev. Med. 51 (14), 2541–2547 (2024).

Yanbing, W. A. N. G. & Lezhen, F. E. N. G. Current situation and prevention countermeasures of pneumoconiosis in Chinese coal enterprises. Clean. Coal Technol. 31 (S2), 412–416 (2024).

Occupational Lung Disease Group of Labor Hygiene and Occupational Diseases Branch of Chinese Preventive Medicine Association. Consensus of Chinese experts on pneumoconiosis treatment (2024). J. Environ. Occup. Med. 41 (1), 1–21 (2024).

Akbar, K. A. & Kallawicha, K. Black lung disease among coal miners in Asia: A systematic review. Saf. Health Work 151(2), 123–128 (2024).

Li, G., Hu, J. & Chen, S. A review of dust control/removal methods in metal mines in China. Powder Technol. 430, 119035 (2023).

Feng zhang, Y. et al. Study on air curtain cooperative spray dust removal in heading face based on swirl theory. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10 (6), 108892 (2022).

Shuda, H. et al. Study on the wet dust collection mechanism of metal-based filter screens and the effect of its inclination angle on dust removal performance. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 176, 430–437 (2023).

Dziubak, S. & Dziubak, T. Experimental study of an axial flow cyclone with ongoing dust removal from a settling tank. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process. Intensif. 209, 110167 (2025).

Yang Xiao, X. E. et al. Diffusion Characteristics of Coal Dust Associated with Different Ventilation Methods in Underground Excavation tunnel. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 184, 1177–1191 (2024).

Jianguo, Z. H. E. N. G. et al. Numerical simulation of dust distribution regularities in fully mechanized rock tunneling face with far-pressing-near-absorption ventilation system. Coal Eng. 49 (2), 93–96 (2017).

Bingyou, J. I. A. N. G. et al. Relationship between long pressure short extraction dust removal performance and dust source movement path in comprehensive heading face of coal mines. J. China Coal Soc. 49 (7), 2973–2985 (2024).

Wenjun, X. U. et al. Dust control and dust removal performance of double air curtain ventilation system in fully-mechanized excavation face. Coal Eng. 55 (3), 122–138 (2023).

Wen, N. I. E. et al. Study on the influence of dust extraction parameters on the diffusion law of dust pollution in the fully mechanized excavation face of rock roadways. Met. Mine 53(5), 110–117 (2024).

Yanjiao, Z. H. A. N. G. et al. Influence of dust source location in fully-mechanized excavation face on location of negative pressure Suction opening. China Saf. Sci. J. 31 (4), 147–155 (2021).

Hao, W. A. N. G. et al. Effect of the forced-suction airflow volume ratio on the dust suppression of swirling air curtain in fully mechanized excavation face. Min. Saf. Environ. Prot. 49, 117–121 (2022).

Xiaoyan, G. O. N. G. et al. Study on airflow intelligent control model of fully mechanized heading face based on BP neural network. Saf. Environ. Eng. 30 (6), 138–145 (2023).

Xiaoyan, G. O. N. G., Tianshu, W. A. N. G. & Long, C. et a1. Research on dust settlement under mixed air flow control in fully mechanized excavation face. J. Mine Autom. 50(2), 106–115 (2024).

Kurnia, J. C., Sasmito, A. P. & Mujumdar, A. S. Dust dispersion and management in underground mining faces. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 24, 39–44 (2014).

Haoyu Wang, B. et al. Analysis of dust pollution characteristics in the respiratory risk zone of the roadway under multiple factors. Energy 305, 132298 (2024).

Toraño, J., Torno, S., Menéndez, M. & Gent, M. Auxiliary ventilation in mining roadways driven with roadheaders: validated CFD modelling of dust behaviour. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 26, 201–210 (2011).

Xiaojiao Cai, W. et al. An assessment of the dust suppression performance of a hybrid ventilation system during the tunnel excavation process: Numerical simulation. Proc. Saf. Environ. Prot. 152, 304–317 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Determination of the optimal axial-to-radial flow ratio of the wall-mounted swirling ventilation in fully mechanized excavation face. Powder Technol. 360, 890–910 (2020).

Jinlin, Q. I. A. O. et al. Simulation study on influence of different factors change on dust migration in long pressure and short Suction dedusting system. Coal Mine Mach. 42 (9), 187–191 (2021).

Zheng, Z. H. A. O. & Guiling, L. I. N. Research on spatiotemporal field function of respirable dust concentration in fully mechanized excavation working face. Min. Saf. Environ. Prot. 51(1), 19–26 (2024).

Hengyuan, F. E. N. G. et al. Study on dust migration law and enrichment characteristics of fully-mechanized heading face in high gas mines. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 19 (10), 59–65 (2023).

Lu Xinxiao, H. & Yujia, H. Research on dust control with wall attachment fan drum in the underground heading face. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 5 (4), 401–408 (2020).

LI Jun. Research progress of dust removal technology based on wall-mounted duct in fully-mechanized driving face. Coal Sci. Technol. 48 (11), 52–59 (2020).

Shengdong, X. U. et al. Research on distribution of radial and axial flow field in vortex dust control system. China Energy Environ. Prot. 46 (8), 55–60 (2024).

YANG Junlei. Influence of ratio of axial and radial air and distance of axial and radial wind on dust control effect. J. Heilongjiang Univ. Sci. Technol. 32 (2), 180–184 (2022).

Jianguo, W. A. N. G. & Yaoyao, L. I. Influence of outlet parameters of wall attached air duct on dust control effect in heading face. Saf. Coal Mines. 54 (10), 50–55 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Chongqing Natural Science Foundation Doctoral “Direct Train” Project (CSTB2023NSCQ-BSX0013), Key Project of Science and Technology Innovation and Entrepreneurship Fund of China Coal Science and Industry Group Co., Ltd (2022-2-TD-ZD011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lei Zheng: conceptualization, methodology. Shengdong Xu: formal Analysis, original draft writing. Zhiquan Ding: investigation, validation. Yangming Xu: Investigation, visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, L., Xu, S., Ding, Z. et al. Research on evaluation method for airflow control effect of long-pressure and short-suction dust removal system in heading faces. Sci Rep 15, 22619 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07216-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07216-x