Abstract

The purpose of this study was to elucidate the effect of second polar body (Pb2) extrusion time on dynamic cleavage parameters and embryonic developmental potential. Data on a total of 398 cycles from patients who underwent intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) treatment between September 2021 and May 2023 were retrospectively analysed. Our results revealed that the average Pb2 extrusion time after ICSI was 3.13 ± 1.63 h and was negatively correlated with Day3 high-quality embryos (odds ratio [OR] = 0.857, CI: 0.810–0.907, P < 0.001) and the blastocyst formation (OR = 0.806, CI: 0.752–0.864, P < 0.001) and high-quality blastocyst formation (OR = 0.755, CI: 0.669–0.851, P < 0.001) but was positively associated with direct cleavage (DC) (OR = 1.081, CI: 1.026–1.139, P = 0.004) and chaotic cleavage (CC) (OR = 1.148, CI: 1.081–1.220, P < 0.001). The Day3 high-quality embryo rate and blastocyst formation rate and high-quality blastocyst formation rate of the > 5 h group were significantly lower than those of the 0–3 h, > 3–4 h and > 4–5 h groups (P < 0.05), while the percentages of DC and CC in the > 5 h group were significantly greater than those in the 0–3 h group (P < 0.05). As the Pb2 extrusion time increased, other embryonic development parameters also significantly increased, including time to pronuclear appearance (r = 0.697, P < 0.001), time to pronuclear fading (r = 0.291, P < 0.001), time to the two cells (r = 0.306, P < 0.001), time to the four cells (r = 0.203, P < 0.001), time to the eight cells (r = 0.138, P < 0.001), time to full blastocyst formation (r = 0.128, P < 0.001), and duration of the time period from three cells to four cells (r = 0.076, P < 0.001). The results of fresh embryo transfer revealed that the clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) and implantation rate (IR) were significantly lower in the Pb2 extrusion delay group than in the Pb2 extrusion normal group (P < 0.05). Overall, delayed Pb2 extrusion was significantly associated with reduced embryonic developmental efficiency, which may be due to a slower speed of development and a significant increase in the incidence of abnormal cleavage. Moreover, transfer of embryos with delayed Pb2 extrusion may impair pregnancy outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infertility is a major reproductive health problem that affects 15% of couples of childbearing age worldwide1. Currently, assisted reproductive technology (ART) is the most effective treatment method for infertile couples seeking to conceive. To date, more than 10 million babies have been conceived via ART2. However, although ART has continued to undergo development in recent years, its rate of success has not significantly improved. Indeed, today, more than half of ART cycles fail to result in pregnancy3. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the mechanisms underlying early embryonic development is crucial.

In recent years, time-lapse imaging has been widely used in the field of assisted reproduction as a noninvasive method for assessing embryo quality. Uninterrupted recording of various physiological events during embryonic development can be achieved by combining a culture system with imaging technology4. Numerous morphokinetic parameters have been introduced for assessing embryonic development and predicting implantation success to improve embryo selection5,6. In addition to accurately monitoring related dynamic parameters, time-lapse imaging can reveal specific dysmorphisms in embryonic development, such as abnormal cleavage and multinucleation (MN)7, thus providing more valuable predictive indicators for in vitro embryonic development.

Research on early embryonic development has been receiving increased attention in recent years. Many studies have shown that early embryonic morphokinetic events play a more critical role in embryonic development than late morphogenetic events5,8,9. Among these, second polar body (Pb2) extrusion is a hallmark morphological event observed after sperm activate oocyte, thereby marking the completion of the second meiotic division of the oocyte. However, previous studies related to Pb2 have been overlooked. Our previous study revealed that Pb2 extrusion during intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles can accurately predict fertilization outcomes10. Additionally, Jin et al. demonstrated that the Pb2 is involved in the regulation of embryonic fate11. Moreover, the morphology of the Pb2 and the relative position between the first polar body and the Pb2 are closely related to embryonic development12,13. However, these observations contradict the viewpoints that the Pb2 is a tiny cell that is unnecessary for embryonic development14. Therefore, further exploration of the clinical applicability of the Pb2 extrusion time in predicting embryonic development efficiency and clinical outcomes is warranted.

This study involved a retrospective analysis of the data of couples who underwent ICSI treatment cycles. Pb2 extrusion and embryonic development were dynamically monitored via time-lapse imaging, and embryonic development indicators and clinical pregnancy outcomes were evaluated. The purpose of this study was to explore the effects of Pb2 extrusion time on dynamic cleavage parameters and the developmental potential of the embryo.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

This was a retrospective study of the data of couples who underwent ICSI treatments between September 2021 and May 2023 at the People’s Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) ICSI cycles monitored via time-lapse imaging, and (2) at least 2 MII oocytes available for ICSI. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) oocyte thawing cycle; (2) artificial oocyte activation cycle; or (3) cycles that occurred without observation of a surviving oocyte after injection. We divided the oocytes into four groups according to the average Pb2 extrusion time observed after ICSI: the 0–3 h group, the > 3–4 h group, the > 4–5 h group and the > 5 h group. In addition, to explore the relationship between the Pb2 extrusion time and clinical pregnancy outcomes, we defined a Pb2 extrusion time > 3 h as delayed Pb2 extrusion; this time was chosen as the average Pb2 extrusion time in this study was 3.13 ± 1.63 h.

Patients who underwent fresh embryo transfer were divided into three groups: (1) the Pb2 extrusion normal group, in which all of the transferred embryos had a Pb2 extrusion time ≤ 3 h; (2) the Mix group, in which one transferred embryo had a Pb2 extrusion time ≤ 3 h and the other embryo had a Pb2 extrusion time > 3 h; and (3) the Pb2 extrusion delay group, in which all of the transferred embryos had a Pb2 extrusion time > 3 h.

Oocyte retrieval, ICSI fertilization and time-lapse monitoring

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation was performed using one of several protocols, including those involving gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, GnRH antagonists, progestin-primed ovarian stimulation, or mini-stimulation. Oocytes were retrieved via transvaginal aspiration under ultrasound guidance 36 h after the injection of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). After the retrieved oocytes were precultured in G-IVF PLUS™ (10136, Vitrolife) for 3 h, the cumulus cells surrounding the oocytes were removed with 80 IU/ml hyaluronidase, then the ICSI was performed. The MII oocytes were then transferred into G-1 PLUS™ (10128, Vitrolife) in a Primo Vision dish (9-well or 16-well, Vitrolife) covered with mineral oil (Vitrolife) and subsequently cultured in a Primo Vision incubator (Vitrolife, Budapest, Hungary) at 37 °C, 6% CO2, and 5% O2. Primo Vision time-lapse system was installed in the incubator and connected to the Analyzer image analysis software (Version: 4.4.1.01.010). The shooting interval was set to 10 min, and the scanning interval of 7 equidistant focal planes was set to 60 min. We defined t0 as the mid-time point from when injection began and ended for that patient’s cohort of oocytes15 and used a time-lapse method to record and analyse the time points of the following events: time to Pb2 extrusion (tPb2); time to pronuclear appearance (tPNa) ; time to pronuclear fading (tPNf) ; time to the two cells(t2), time to the four cells (t4) and time to the eight cells (t8); time to full blastocyst formation (tB); time to the end of the expansion phase and initiation of the hatching process of the blastocyst (tHN); duration from pronuclear fading to the five cells (t5-tPNf); duration from Pb2 extrusion to the two cells (CC1); duration from the three cells to the four cells (S2); and duration from the five cells to the eight cells (S3). The time points of all the above dynamic developmental parameters were double-checked and confirmed by two experienced embryologists.

Embryo quality assessment and transfer

Fertilization status was evaluated at 16–18 h after ICSI; during this period, the observation of two pronuclei and two polar bodies was defined as normal fertilization16. On the third day, factors such as the number of blastomeres, blastomere symmetry, and fragmentation rate were used as the basis for evaluating the quality of the cleavage-stage embryos. Day3 embryos with more than 7 cells derived from normal fertilized oocytes and an embryo grade of 1–2 were defined as high-quality embryos. On the fifth/sixth days, the quality of the blastocysts was evaluated according to the Gardner scoring standard; specifically, blastocysts with scores of 4BB and above were defined as high-quality blastocysts, whereas those with scores better than 3BC or 3CB were defined as available blastocysts.

The definitions of abnormal cleavage patterns were as follows7,17. Direct cleavage (DC) was defined as the direct cleavage of an embryo from 1 cell to > 2 cells. Reverse cleavage (RC) was defined as the recombination of two completely separate cells into one cell. Chaotic cleavage (CC) was defined as disordered cleavage behaviour, resulting in unevenly sized blastomeres and numerous fragments. MN was defined as the appearance of multiple pronuclei in any cell at the 2-cell or 4-cell stage. An embryo with multiple abnormal cleavage patterns corresponding to at least two of DC, RC, CC and MN was defined as a mixed abnormal cleavage (Mix) embryo.

One or two embryos were transferred into the uterine cavity on the day of transfer. All cleavage-stage embryos were transferred on the third day, and all blastocyst-stage embryos were transferred on the fifth day. Clinical pregnancy was defined as the presence of one or more gestational sacs in the uterus and confirmation of a foetal heartbeat via ultrasound examination on the 4th week after embryo transfer. Early miscarriage was defined as miscarriage before 12 weeks. Live birth was defined as any birth event in which at least one baby was born alive and survived for more than 1 month.

Statistical analysis

All of the statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, SPSS Statistics). Quantitative data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (\(\overline{x}\)±s), and categorical data are presented as percentages (%). Spearman correlation analysis and binary logistic regression analysis were performed with Pb2 extrusion time as the independent variable and embryo development efficiency indicators, time parameters and cleavage pattern as the dependent variables to determine the association between the Pb2 extrusion time and embryonic developmental potential. The Mann‒Whitney U test was used to compare all data between the groups except for rates, which were compared between the groups with the chi-square test. A P value < 0.05 indicated that the corresponding difference was statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. All enrolled patients signed an informed consent form. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region People’s Hospital (Approval No: LL-KY-SY-2021-16).

Results

In total, 398 ICSI cycles were included in this study. The average age of the females was 32.27 ± 4.64 years, and the average age of the males was 35.15 ± 6.13 years. In total, 4913 oocytes were collected, among which 3931 MII oocytes underwent ICSI, with a fertilization rate of 79.85% (3139/3931) (Table 1). In total, 3118 MII oocytes demonstrated Pb2 extrusion. The 2PN fertilization rate of these oocytes was 94.71% (2953/3118), whereas that of oocytes without Pb2 extrusion was 2.46% (20/813). The average Pb2 extrusion time after ICSI was 3.13 ± 1.63 h. The distributions of the Pb2 extrusion times were as follows: 0–3 h (54.94%), > 3–4 h (29.41%), > 4–5 h (9.62%) and > 5 h (6.03%) (Fig. 1).

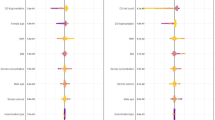

Figure 2 shows the binary logistic regression results between Pb2 extrusion time and embryonic developmental outcomes and abnormal cleavage patterns. Our results revealed that Pb2 extrusion time was significantly associated with various embryonic development parameters and abnormal cleavage patterns. Specifically, the Pb2 extrusion time was negatively associated with the embryonic 2PN fertilization (odds ratio [OR] = 0.987, 95% CI: 0.850–0.946, P < 0.001), 2PN cleavage (OR = 0.867, 95% CI: 0.760–0.989, P = 0.034), Day3 high-quality embryos (OR = 0.857, 95% CI: 0.810–0.907, P < 0.001), blastocyst formation (OR = 0.806, 95% CI: 0.752–0.864, P < 0.001), high-quality blastocyst formation (OR = 0.755, 95% CI: 0.669–0.851, P < 0.001) and available blastocyst formation (OR = 0.800, 95% CI: 0.739–0.866, P < 0.001) but was positively associated with abnormal embryo cleavage (OR = 1.088, 95% CI: 1.037–1.142, P = 0.001), DC (OR = 1.081, 95% CI: 1.026–1.139, P = 0.004) and CC (OR = 1.148, 95% CI: 1.081–1.220, P < 0.001).

Binary logistic regression results of the effects of Pb2 extrusion time on embryonic developmental outcomes and abnormal cleavage patterns. DC direct cleavage, RC reverse cleavage, CC chaotic cleavage, MN Multinucleation, Mix mixed abnormal cleavage. A P value < 0.05 indicates that the difference is statistically significant.

Figure 3 shows the results of Spearman correlation analysis between the Pb2 extrusion time and embryonic development and time parameters. Our results revealed that as the Pb2 extrusion time increased, the number of Day3 blastomeres significantly decreased (r=-0.136, P < 0.001), and the Day3 embryo grade increased (r = 0.069, P < 0.001). In addition, the Pb2 extrusion time was also correlated with various temporal embryonic developmental parameters. Specifically, as the Pb2 extrusion time increased, the tPNa (r = 0.697, P < 0.001), tPNf (r = 0.291, P < 0.001), t2 (r = 0.306, P < 0.001), t4 (r = 0.203, P < 0.001), t8 (r = 0.138, P < 0.001), tB (r = 0.128, P < 0.001), and S2 (r = 0.076, P < 0.001) significantly increased.

Results of Spearman correlation analysis between Pb2 extrusion time and embryonic development and time parameters. tPNa time to pronuclear appearance, tPNf time to pronuclear fading, t2 time to the two cells, t4 time to the four cells, t8 time to the eight cell, tB time to full blastocyst formation, tHN time to the end of the expansion phase and initiation of the hatching process of the blastocyst, CC1 = t2-tPb2; S2 = t4-t3; S3 = t8-t5. A P value < 0.05 indicates that the difference is statistically significant.

Table 2 shows the results of the comparison of embryonic developmental outcomes and abnormal cleavage patterns among the four groups. The 2PN fertilization rate in the > 5 h group was significantly lower than that in the 0–3 h group, > 3–4 h group and > 4–5 h group (85.11% vs. 94.86%, P < 0.001; 85.11% vs. 96.29%, P < 0.001; 85.11% vs. 95.00%, P < 0.001; respectively). The Day3 high-quality embryo rates in the > 3–4 h group and > 5 h group were significantly lower than those in the 0–3 h group (51.94% vs. 58.36%, P = 0.002; 40.76% vs. 58.36%, P < 0.001; respectively). Additionally, the Day3 high-quality embryo rate in the > 5 h group was significantly lower than that in the > 3–4 h group and > 4–5 h group (40.76% vs. 51.94%, P < 0.001; 40.76% vs. 52.82%, P < 0.001, respectively). The blastocyst formation rates of the > 3–4 h group, > 4–5 h group and > 5 h group were lower than those of the 0–3 h group (57.95% vs. 65.86%, P = 0.001; 52.36% vs. 65.86%, P < 0.001; 39.34% vs. 65.86%, P < 0.001; respectively). Moreover, the blastocyst formation rate of the > 5 h group was significantly lower than that of the > 3–4 h group and > 4–5 h group (39.34% vs. 57.95%, P < 0.001; 39.34% vs. 52.36%, P = 0.025, respectively). The high-quality blastocyst formation rates of the > 3–4 h group, > 4–5 h group and > 5 h group were lower than those of the 0–3 h group (12.01% vs. 19.25%, P < 0.001; 10.99% vs. 19.25%, P = 0.006; 4.10% vs. 19.25%, P < 0.001, respectively). In addition, the high-quality blastocyst formation rate of the > 5 h group was significantly lower than that of the > 3–4 h group and > 4–5 h group (4.10% vs. 12.01%, P < 0.010; 4.10% vs. 10.99%, P = 0.031, respectively). The abnormal cleavage rates of the > 3–4 h group and > 5 h group were significantly greater than those of the 0–3 h group (39.98% vs. 34.79%, P = 0.010; 43.95% vs. 34.79%, P = 0.022; respectively). The percentage of DC in the > 5 h group was significantly greater than that in the 0–3 h group and > 3–4 h group (21.66% vs. 12.46%, P = 0.001; 21.66% vs. 12.87%, P = 0.004, respectively). Furthermore, the percentages of CC in the > 3–4 h group and > 5 h group were significantly greater than those in the 0–3 h group (5.81% vs. 3.82%, P = 0.023; 8.92% vs. 3.82%, P = 0.003, respectively).

Table 3 shows the results of the comparisons of embryonic development and time parameters among the four groups. The average number of blastomeres on Day3 in the > 3–4 h group, > 4–5 h group and > 5 h group was significantly lower than that in the 0–3 h group (P < 0.001, P = 0.001, and P < 0.001, respectively). The average number of blastomeres on Day3 in the > 5 h group was significantly lower than that in the > 3–4 h group and > 4–5 h group (P < 0.001 and P = 0.002, respectively). The average Day3 embryo grades in the > 3–4 h group and > 5 h group were significantly greater than those in the 0–3 h group (P = 0.002 and P < 0.001, respectively). Moreover, the average Day3 embryo grade in the > 5 h group was significantly greater than that in the > 3–4 h group and the > 4–5 h group (P = 0.032 and P = 0.009, respectively). The values of the time parameters (tPb2, tPNa, tPNf, t2, t4, and t8) of the > 3–4 h group, > 4–5 h group and > 5 h group were significantly greater than those of the 0–3 h group (all P < 0.001). Moreover, the tB values in the > 3–4 h group, > 4–5 h group and > 5 h group were significantly greater than those in the 0–3 h group (P < 0.001, P = 0.005, and P = 0.005, respectively). The S2 values in the > 3–4 h group and > 5 h group were significantly greater than those in the 0–3 h group (P = 0.002 and P > 0.001, respectively). The differences in tHN, tPNf-t5, CC1 and S3 among the groups were not significant (P > 0.05).

In total, 261 fresh embryo transfer cycles were performed, and the differences in average age, body mass index (BMI), infertility duration, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) level, average number of retrieved oocytes and endometrial thickness on the day of hCG administration were not significant (P > 0.05) (Table 4). Additionally, the clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) of the Pb2 extrusion delay group was significantly lower than that of the Pb2 extrusion normal group (48.44% vs. 67.74%, respectively; P = 0.015). The implantation rates (IRs) of the Mix group and Pb2 extrusion delay group were significantly lower than those of the Pb2 extrusion normal group (36.06% vs. 47.65%, P = 0.023; 31.62% vs. 47.65%, P = 0.007; respectively). Furthermore, the differences in the early miscarriage rate (EMR) and live birth rate (LBR) among the three groups were not significant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between the Pb2 extrusion time, as monitored via time-lapse, and the dynamic patterns of embryonic cleavage and developmental potential. Our results revealed that Pb2 extrusion time was significantly associated with embryonic developmental efficiency, developmental speed and abnormal cleavage pattern. Delayed extrusion of Pb2 significantly reduced embryonic developmental efficiency, possibly due to the slower developmental speed and the significant increase in abnormal cleavage observed for the corresponding groups. In addition, delayed Pb2 extrusion may negatively affect clinical pregnancy outcomes following embryo transfer.

During fertilization, sperm enter the oocyte cytoplasm and induce Ca2+ oscillations to activate the oocyte, complete the second meiotic division, and cause Pb2 extrusion18. Therefore, Pb2 extrusion is a hallmark morphological event observed after sperm activate oocyte and may be closely related to fertilization and early embryonic development. The results of this study revealed that the normal fertilization rate of oocytes exhibiting Pb2 extrusion was as high as 94.71%, whereas the normal fertilization rate of oocytes that did not exhibit Pb2 extrusion was only 2.46%, which are consistent with the results of a previous study19. These findings confirmed that Pb2 extrusion is a valuable predictor for assessing fertilization early.

In our study, we observed a significant correlation between Pb2 extrusion time and both embryonic developmental speed and markers of embryonic developmental potential. An earlier Pb2 extrusion time corresponded to earlier points in time at which each physiological event in the embryonic developmental process can be monitored. In addition, the developmental efficiency of embryos exhibiting earlier Pb2 extrusion times was greater than that of embryos exhibiting later Pb2 extrusion times. Previous study has demonstrated that delayed oocyte activation can prolong the fertilization time and affect embryonic development20. Oocytes are activated earlier to complete the second stage of meiosis, and thus sperm-derived chromatin and oocyte-derived chromatin form male and female pronuclei, respectively, which is not only conducive to the timely initiation of mitosis but also prevents the negative effects of oocyte ageing in vitro. However, oocyte activation is a complex and regulated process, and it is generally believed that the Ca2+ oscillation is the key to successful oocyte activation21,22. Studies have shown that defects in sperm quality can lead to abnormal Ca2+ oscillation patterns in oocytes, thereby affecting the fertilization process23,24. During the ICSI cycles, the time at which the sperm entered the oocyte cytoplasm was essentially the same. Additionally, delayed extrusion of the Pb2 potentially indicated disordered sperm activation, thus leading to problems in the oocyte activation process. Moreover, sperm factors are also important for determining embryonic developmental potential. In human embryos, after maternal genome controls are transformed at the 8–16-cell stage, the paternal genome begins to be transcriptionally activated and participates in regulating the embryonic developmental process25. These findings may partially explain why the blastocyst formation rate in the group with the longest Pb2 extrusion times was significantly lower than that in the other groups in this study.

Interestingly, in this study, we observed a significant positive correlation between the Pb2 extrusion time and the risk of abnormal embryo cleavage, especially that of the DC or CC patterns. Moreover, previous studies have demonstrated that abnormal cleavage is an important factor leading to decreased embryonic developmental efficiency7,26. This may explain the significantly impaired embryonic developmental potential observed in this study. Regarding the underlying mechanism, we speculate that it may involve defects in oocyte and sperm quality. Delayed Pb2 extrusion may indicate underlying functional deficiencies in either the oocyte or sperm, leading to delayed activation of oocyte. In addition, study has shown that compromised oocyte quality contributes to the formation of abnormal spindles, resulting in abnormal cleavage27. Furthermore, sperm factors, such as centriole defects and high sperm DNA fragmentation levels, can also significantly increase the risk of abnormal cleavage28,29. Nevertheless, the exact mechanisms remains to be elucidated through further fundamental experimental investigations in future work.

It is worth noting that we also found that delayed Pb2 extrusion significantly impaired embryonic implantation potential. Although fewer embryos were transferred in the Pb2 extrusion normal group, the CPR and IR were obviously greater than in the Pb2 extrusion delay group. This was consistent with our previous observation that delayed Pb2 extrusion led to increased abnormal cleavage and decreased efficiency of blastocyst development. What’s remarkable is that some embryos exhibiting delayed Pb2 extrusion in this study still achieved pregnancy. This may be attributed to the embryo’s self-correction ability. Study has demonstrated that embryos with severe abnormal cleavage can result in live births once they form full blastocysts30. This suggests that culturing embryos with delayed Pb2 extrusion to the blastocyst stage for further screening before transfer may serve as a viable strategy to improve pregnancy outcomes.

Currently, many morphokinetic parameters have been incorporated algorithms and AI models, which have been proven to effectively improve embryo selection strategies31,32,33,34. Therefore, our findings provide more references for integrating Pb2 extrusion time into embryo selection algorithms and AI, which may improve ART success rates.

However, this study has several limitations. First, this study involved a retrospective analysis, and the included embryo transfer cycles were not strictly controlled to ensure single-embryo transfers. Therefore, further multicentre, prospective, randomized controlled trials should be conducted in the future to verify these findings. Second, this study included only infertile patients who underwent ICSI treatments because the cumulus‒oocyte complexes (COCs) were attached to the zona pellucida of oocytes fertilized via IVF; thus, Pb2 extrusion could be dynamically monitored only for preremoved COCs during the ICSI cycles.

Conclusion

The results of this retrospective, time-lapse study confirmed that the Pb2 extrusion time is a valuable indicator for predicting the dynamic pattern of embryonic cleavage and embryonic developmental potential. A slower developmental speed and increased risk of abnormal embryonic cleavage may be indicators of reduced developmental efficiency in embryos with delayed Pb2 extrusion. In addition, delayed Pb2 extrusion may negatively impact clinical pregnancy outcomes after embryo transfer. In general, Pb2 extrusion which represents the hallmark morphological indicator after sperm cells activate oocyte may be closely related to embryonic developmental potential, warrants further study.

Data availability

The original data supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Łakoma, K. et al. The influence of metabolic factors and diet on fertility. Nutrients 15 (5) (2023).

Pinborg, A. et al. Long-term outcomes for children conceived by assisted reproductive technology. Fertil. Steril. 120 (3 Pt 1), 449–456 (2023).

Smeenk, J. et al. ART in europe, 2019: results generated from European registries by ESHRE†. Hum. Reprod. 38 (12), 2321–2338 (2023).

Minasi, M. G. et al. The clinical use of time-lapse in human-assisted reproduction. Ther. Adv. Reprod. Health. 14, 2633494120976921 (2020).

Meseguer, M. et al. The use of morphokinetics as a predictor of embryo implantation. Hum. Reprod. 26 (10), 2658–2671 (2011).

Basile, N. et al. What does morphokinetics add to embryo selection and in-vitro fertilization outcomes? Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 27 (3), 193–200 (2015).

Desai, N. et al. Are cleavage anomalies, multinucleation, or specific cell cycle kinetics observed with time-lapse imaging predictive of embryo developmental capacity or ploidy? Fertil. Steril. 109 (4), 665–674 (2018).

Barberet, J. et al. Can novel early non-invasive biomarkers of embryo quality be identified with time-lapse imaging to predict live birth? Hum. Reprod. 34 (8), 1439–1449 (2019).

Mizobe, Y. et al. Effects of early cleavage patterns of human embryos on subsequent in vitro development and implantation. Fertil. Steril. 106 (2), 348–353 (2016).

Xue, L. et al. Early rescue oocyte activation at 5 h post-ICSI is a useful strategy for avoiding unexpected fertilization failure and low fertilization in ICSI cycles. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1301505 (2023).

Jin, H. et al. The second Polar body contributes to the fate asymmetry in the mouse embryo. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9 (7), nwac003 (2022).

Zhou, W. et al. Relationship of Polar bodies morphology to embryo quality and pregnancy outcome. Zygote 24 (3), 401–407 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. Optimal Polar bodies angle for higher subsequent embryo viability: a pilot study. Fertil. Steril. 105 (3), 670–675 (2016).

Schenk, M. et al. Impact of Polar body biopsy on embryo morphokinetics-back to the roots in preimplantation genetic testing? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 35 (8), 1521–1528 (2018).

Ciray, H. N. et al. Proposed guidelines on the nomenclature and annotation of dynamic human embryo monitoring by a time-lapse user group. Hum. Reprod. 29 (12), 2650–2660 (2014).

The Istanbul consensus workshop on embryo assessment: proceedings of an expert meeting. Hum. Reprod. 26 (6), 1270–1283 (2011).

Athayde Wirka, K. et al. Atypical embryo phenotypes identified by time-lapse microscopy: high prevalence and association with embryo development. Fertil. Steril. 101 (6), 1637–1648 (2014).

Saleh, A. et al. Essential role of sperm-specific PLC-zeta in egg activation and male factor infertility: an update. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 8, 28 (2020).

Jin, H. et al. The value of second Polar body detection 4 hours after insemination and early rescue ICSI in preventing complete fertilisation failure in patients with borderline semen. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 26 (2), 346–350 (2014).

Shiraiwa, Y. et al. Clinical outcomes of rescue intracytoplasmic sperm injection at different timings following in vitro fertilization. J. Reprod. Infertil. 22 (4), 251–257 (2021).

Bonte, D. et al. Assisted oocyte activation significantly increases fertilization and pregnancy outcome in patients with low and total failed fertilization after intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a 17-year retrospective study. Fertil. Steril. 112 (2), 266–274 (2019).

Sfontouris, I. A. et al. Artificial oocyte activation to improve reproductive outcomes in women with previous fertilization failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Hum. Reprod. 30 (8), 1831–1841 (2015).

Parrella, A. et al. Phospholipase C zeta in human spermatozoa: A systematic review on current development and clinical application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (2), 1 (2024).

Kashir, J. Increasing associations between defects in phospholipase C zeta and conditions of male infertility: not just ICSI failure? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 37 (6), 1273–1293 (2020).

Liao, C. et al. Ratio of the zygote cytoplasm to the paternal genome affects the reprogramming and developmental efficiency of androgenetic embryos. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 87 (4), 493–502 (2020).

Shavit, M. et al. Cleavage patterns of 9600 embryos: the importance of irregular cleavage. J. Clin. Med. 12 (17), 1 (2023).

Zheng, W. et al. New biallelic mutations in PADI6 cause recurrent preimplantation embryonic arrest characterized by direct cleavage. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 37 (1), 205–212 (2020).

Rubio, I. et al. Limited implantation success of direct-cleaved human zygotes: a time-lapse study. Fertil. Steril. 98 (6), 1458–1463 (2012).

Wang, S. et al. Sperm DNA fragmentation measured by sperm chromatin dispersion impacts morphokinetic parameters, fertilization rate and blastocyst quality in ICSI treatments. Zygote 30 (1), 72–79 (2022).

Lee, T. et al. Abnormal cleavage up to day 3 does not compromise live birth and neonatal outcomes of embryos that have achieved full blastulation: a retrospective cohort study. Hum. Reprod. 39 (5), 955–962 (2024).

Ezoe, K. et al. Association between a deep learning-based scoring system with morphokinetics and morphological alterations in human embryos. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 45 (6), 1124–1132 (2022).

Bamford, T. et al. A comparison of 12 machine learning models developed to predict ploidy, using a morphokinetic meta-dataset of 8147 embryos. Hum. Reprod. 38 (4), 569–581 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Time-lapse deselection model for human day 3 in vitro fertilization embryos: the combination of qualitative and quantitative measures of embryo growth. Fertil. Steril. 105 (3), 656–662 (2016).

Bori, L. et al. The higher the score, the better the clinical outcome: retrospective evaluation of automatic embryo grading as a support tool for embryo selection in IVF laboratories. Hum. Reprod. 37 (6), 1148–1160 (2022).

Funding

The Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of China (grant numbers 2024GXNSFDA010006 and 2023GXNSFAA026011) and the Research Programme of Guangxi health commission (grant number S2023016) supported this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. S.W. and Y.P. collected the time-lapse data and performed the statistical analysis. X.M., Z.L., X.Z., and P.W. performed the ICSI procedure, embryo assessment, and data recording. J.Q. and L.L. recruited patients and obtained consent for participation. L.C., Y.H., and W.S. collected and screened the clinical data. L.X. obtained funding and revised the manuscript. All of the authors contributed to this article and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Wang, S., Mao, X. et al. Delayed second polar body extrusion increases abnormal cleavage risk and impairs embryonic developmental potential: a retrospective time-lapse study. Sci Rep 15, 21786 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07247-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07247-4