Abstract

To investigate the mechanical properties of concrete-foamed cement composite specimens (C-FCCS), uniaxial compression tests were conducted on composite specimens with varying proportions and strengths of foamed cement. The analysis focused on the peak compressive strength, peak strain, macroscopic failure morphology, and acoustic emission (AE) characteristics of C-FCCS. The experimental results indicate that the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS exhibits a negative correlation with the proportion of foamed cement and a positive correlation with the proportion of concrete. At foamed cement proportions of 10% and 20%, the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS is predominantly governed by concrete, with AE energy concentrated primarily during the initial loading phase and near the peak stress. In contrast, at foamed cement proportions ranging from 30 to 50%, the peak compressive strength is dominated by foamed cement, with AE energy concentrated around the peak stress. The peak strain of C-FCCS shows a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing with the increase in height ratio (Height ratio = Foamed cement height/C-FCCS height). Under different height ratios, the peak strain of C-FCCS is approximately 175.61–558.13% of that of pure concrete specimens. Furthermore, variations in the strength of foamed cement have a minimal impact on the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS but significantly affect the peak strain. The peak compressive strength of C-FCCS is about 77.67–83.87% of that of pure concrete specimens, while the peak strain ranges from 128.46 to 361.38%. Lastly, the macroscopic failure of C-FCCS is primarily characterized by tensile failure, with shear failure commonly observed at the edges and corner interfaces of C-FCCS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of gob-side entry retaining as a coal pillarless mining technique offers unparalleled advantages in enhancing coal resource recovery rates and reducing the volume of roadway excavation, positioning it as a significant development direction for green mining in China’s coal industry1,2. The side backfilling body, serving as the primary structure for supporting the roadway roof and isolating goaf, plays a crucial role in determining the success or failure of gob-side entry retaining3. Currently, the side backfilling body in gob-side entry retaining is primarily categorized into rigid material filling and flexible material filling4,5. The former exhibits poor compressibility and is prone to shear failure of the roadway roof under high-stress conditions6,7. Conversely, the latter struggles to control the lateral displacement of the roadway under high stress8, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The composite backfilling technology for gob-side entry retaining is key to addressing these issues. This technology constructs a composite backfilling body that forms a "rigid-flexible" coexistence structure to meet the stress and deformation requirements of the side backfilling body (Fig. 1). The mechanical properties of the composite backfilling body are one of the critical factors influencing the success of gob-side entry retaining and hold significant implications for the safe production of coal mines. Therefore, conducting experimental studies on the mechanical properties of concrete-foamed cement composite specimens under uniaxial compression is vital for engineering applications.

Current research on the mechanical properties of "rigid-flexible" composite specimens primarily focuses on rock composite specimens9, coal-rock composite specimens10,11, and rock-filling composite specimens12. Sun et al.9 conducted uniaxial compression tests on composite specimens of mudstone/siltstone, mudstone/fine sandstone, fine sandstone/siltstone, and siltstone/mudstone/fine sandstone. The test results indicate that as the proportion of soft rock in the composite structure increases, the primary failure modes of the specimens are tensile failure and single-plane shear failure. Ma et al.13 demonstrate that the mechanical properties of coal-rock composites gradually decrease with increasing coal height ratio, and the experimental results reveal a significant loading rate effect on the mechanical properties of coal-rock composites about their acoustic emission characteristics14,15. Chen et al.16 assert that the strength of coal-rock composites primarily depends on the strength of the coal, which is the relatively weaker material within the composite specimens. Failure in coal-rock composite specimens initially occurs through coal failure (which has relatively lower strength), ultimately leading to overall specimen failure. The presence of rock (which has relatively higher strength) enhances the overall deformation resistance of the composite specimens17. In the failure modes of coal-rock composites, the coal primarily exhibits splitting or shear failure, while the rock mass experiences tensile failure or failure due to crack propagation within the coal. Cheng et al.8 found that the uniaxial compressive strength and elastic modulus of coal-rock composites gradually decrease with an increasing proportion of coal in the composite structure. The weight of influencing factors on the mechanical properties of coal-rock composites is ranked as follows: height proportion > coal strength > rock strength > coal-rock interface angle. Furthermore, numerous studies indicate that the interlayer position of soft layers within the composite18,19, the inclination angle of the interface20,21, and confining pressure also affect the mechanical properties and failure modes of the composite specimens22,23. The aforementioned research on composites primarily focuses on rock and coal, with limited attention given to backfilling materials.

Zhang et al.12 conducted uniaxial compression experiments on water–sand backfilling bodies and red sandstone under various ratios, concluding that the strength of the backfilling body influences the overall load-bearing capacity of the composite specimens, a finding corroborated by Zhao et al.24. Gao et al.25 investigated the mechanical properties of granite-concrete composite specimens under different interface roughness and height ratios. The experimental results indicated that under uniaxial loading, the compressive strength of the composite specimens comes closer to that of the lower-strength concrete, and that interface roughness enhances the compressive strength of the composite specimens. Zhang et al.26 considered the mechanical properties of low-strength mortar-granite composite specimens, exploring the effects of interface angle and mortar strength on the failure modes of the composite specimens. The results demonstrated that mortar strength is a primary factor affecting the strength and failure modes of the composite specimens. The greater the strength ratio between the two materials in the composite, the more pronounced the effect of the interface angle. Other scholars have similarly validated these findings27,28. Additionally, Koupouli et al.29 investigated the shear strength of cement slurry composite specimens. However, the aforementioned studies primarily focused on rock-filling composites, with limited research on filling-filling composites. Notably, the impact of height ratio on the overall mechanical performance of composite specimens has received scant attention. This study is intended to conduct relevant experiments to enhance and supplement this area of research.

In summary, while there is a wealth of research on the mechanical behavior of composite specimens, most of it centers on rock-rock composites, rock-coal composites, and rock-filling composites, with fewer reports on the mechanical properties and acoustic emission characteristics of "rigid-flexible" composite specimens. To explore the mechanical properties of "rigid-flexible" composite backfilling, this paper presents uniaxial compression experiments and acoustic emission tests on concrete-foamed cement composite specimens. The test focuses on the mechanical behavior and structural stability of the ' rigid-flexible ' composite specimen and discusses the variation law and failure mode of the mechanical properties of the concrete-foamed cement composite specimen. The research results can provide a reference for the application of composite backfilling technology in gob-side entry retaining.

Experimental materials and methods

Experimental materials and preparation

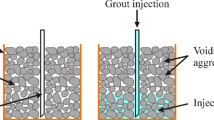

The influence of height ratio and the strength of flexible materials on the mechanical properties of composite specimens surpasses that of other factors18. This experiment primarily investigates the effects of these two factors on the mechanical behavior of composite specimens. Rigid and flexible materials for the composite specimens are selected as concrete5 and foamed cement30, respectively. The concrete specimens, foamed cement specimens, and concrete-foamed cement composite specimens are prepared as 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm cubes in accordance with the national standard GB/T 50,081–2019 (Standard for Testing Methods of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Concrete)26, with the preparation process illustrated in Fig. 2. The composition and proportions of the concrete and foamed cement specimens are detailed in Table 1.

Figure 3 outlines the preparation process for the concrete-foamed cement composite specimens: ① First, the components of the concrete are weighed sequentially according to the designed mix ratio, and the mixture is thoroughly stirred with water before being poured into the mold to the specified height; ② After allowing the concrete mixture to rest for 30 min, the components of the foamed cement are weighed sequentially according to the designed mix ratio, mixed with water, and filled into the mold to a height of 100 mm; ③ The specimens are placed in a curing chamber maintained at a temperature of (20 ± 5)℃ and relative humidity of (95 ± 5)%31, cured for 3 days before demoting, and then continue curing until 28 days32.

Experimental equipment and experimental scheme

Before conducting uniaxial compression tests on C-FCCS, uniaxial compression experiments were performed on pure concrete and foamed cement specimens (100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm) to obtain their mechanical properties. The uniaxial compression tests for C-FCCS were designed with nine experimental scenarios, with each experimental scheme repeated three times, as detailed in Table 2. The testing system comprises a loading system, a photographic system, and an acoustic emission system (Fig. 4). The uniaxial compression tests were executed using a 1000 kN MTS testing machine, with a loading rate of 0.5 MPa/min. The acoustic emission system was equipped with two RS-54A acoustic emission sensors, each with a resonance frequency of 300 kHz, symmetrically positioned at the center of both sides of the specimen. A preamplifier was set to 40 dB, with a threshold value also at 40 dB21,33,34. The definitions for signal peak time (PDT), impact definition time (HDT), and impact lock time (HLT) were established at 50 μs, 100 μs, and 500 μs, respectively35,36. Additionally, a hot melt adhesive gun was utilized as a coupling agent to affix the acoustic emission sensors to the surfaces of the specimens, facilitating the collection of acoustic emission data during specimen failure under load. The acoustic emission data logger was synchronized with the MTS testing machine to ensure the accuracy of the data collected.

Experimental results

Mechanical properties of pure concrete and foamed cement specimens

Figure 5 illustrates the stress–strain curves for pure concrete and foamed cement specimens, with the mechanical properties detailed in Table 3. This study selects the linear slope corresponding to 40–60% of the peak compressive stress as the elastic modulus of the specimens16,36,37,38. As indicated in Table 3, the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of the pure concrete specimens is 38.62 MPa, which is approximately 3.68 times (FC-1), 4.57 times (FC-2), 7.54 times (FC-3), 14.3 times (FC-4), and 24.76 times (FC-5) that of the pure foamed cement specimens. The elastic modulus of the pure concrete specimens is 3.09 GPa, roughly 2.13 times (FC-1), 2.94 times (FC-2), 3.86 times (FC-3), 10.66 times (FC-4), and 15.45 times (FC-5) that of the pure foamed cement specimens. Under uniaxial loading, the peak compressive strength and elastic modulus of the pure concrete specimens significantly exceed those of the foamed cement specimens, with a rapid decline in the post-peak phase of the stress–strain curve, exhibiting pronounced brittle characteristics. In contrast, the stress–strain curves of the foamed cement specimens display distinct plastic characteristics, particularly when the foaming agent content is high (FC-4 and FC-5), where the elastic phase of the curve nearly disappears.

Characteristics of the stress–strain characteristic curve of composite specimens

Figure 6 illustrates the stress–strain curves of C-FCCS, with the typical characteristic curve depicted in Fig. 7. As shown in Fig. 6a–f, the stress–strain characteristic curves of the PC-9-5 ~ PC-8-5 composite specimens can be categorized into seven distinct stages: compaction stage i, elastic stage i, plastic stage i, compaction stage ii, elastic stage ii, plastic stage ii, and post-peaking stage, which are classified as type I characteristic curves.

-

(1)

In compaction stage i, the curve exhibits a concave shape, with a slow increase and a relatively short duration. The internal bubbles of the foamed cement gradually rupture, and the structural inhomogeneity at the layered interfaces contributes to this behavior. These microstructural features gradually close during the initial loading phase, resulting in a slow increase in specimen strength.

-

(2)

During elastic stage i, the curve shows linear growth, albeit still slow. The strength and elastic modulus of the foamed cement are significantly lower than those of the concrete. As the external load increases, the foamed cement transitions into the elastic stage while the concrete remains in the compaction stage, leading to a stress–strain curve that approaches linearity during this phase.

-

(3)

In plastic stage i, under sustained loading, the foamed cement enters the plastic phase. Initially, the curve presents a convex shape, with a significant number of internal cracks developing within the foamed cement. Due to the higher proportion and strength of the concrete compared to the foamed cement, crack propagation during this stage is hindered by interface effects, preventing overall structural instability or failure of the composite specimen.

-

(4)

Compaction stage ii is characterized by a concave curve that increases slowly but persists for a longer duration. Following the failure of the foamed cement, it is gradually compacted, while The pores and microscopic pores inside the concrete are completely closed, resulting in a prolonged secondary compaction phase for the composite specimen.

-

(5)

In the elastic stage ii, the curve exhibits a rapid linear increase. As the internal cracks of the foamed cement and concrete gradually densify post-failure, the composite specimen transitions into linear elastic deformation, resulting in the emergence of a secondary elastic stage in the stress–strain curve. During this phase, the pre-existing internal cracks of the composite specimen gradually close, with no new cracks forming temporarily.

-

(6)

In the plastic stage ii, the duration of this phase is relatively short. With the increase in stress, internal crack initiation and nonlinear propagation in concrete. The curve displays a secondary convex characteristic, although this is not prominently pronounced overall.

-

(7)

In the post-peak stage, internal cracks in the concrete rapidly propagate and extend to the surface of the specimen. The strength of the composite specimen experiences a decline, and the stress–strain characteristic curve exhibits a rapid decrease. This behavior is fundamentally consistent with the post-peak curve characteristics of pure concrete specimens, although the rate of decline diminishes as the proportion of foamed cement increases.

As illustrated in Fig. 6g–i, the stress–strain characteristic curves of the composite specimens PC-7-5 ~ PC-5-5 can be categorized into four stages: compaction stage, elastic stage, plastic stage, and post-peak stage, corresponding to Class II characteristic curves. At this height ratio, the stress–strain curve characteristics of the composite specimens are essentially similar to those of pure foamed cement specimens with the same foaming agent dosage. The curves do not exhibit secondary compaction, elastic, or plastic stages, and the elastic stage is nearly absent, demonstrating significant plastic deformation characteristics. This indicates that the height ratio has a substantial impact on the mechanical behavior of the concrete-foamed cement composite specimens.

As shown in Fig. 6a–e, the stress–strain curves of the composite specimens PC-9-1 ~ PC-9-5 closely align with Class I characteristic curves, suggesting that the strength of the foamed cement has a relatively minor influence on the stress–strain curves of the composite specimens. With the increase of the strength of foamed cement, the change characteristics of the curve ' concave-convex-concave-convex ' are less obvious. Especially when the foaming agent content is 1%, the curve as a whole shows a ' concave-convex ' change.

Analysis of mechanical properties of C-FCCS

Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the variations in peak compressive strength and peak strain of the composite specimens, with the coefficient of variation presented in Table 4, thereby validating the reliability of the experimental data39,40. From the figures and table, it can be observed that the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS exhibits a decreasing trend with an increase in height ratio. Compared to pure concrete specimens, the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS decreased by 18.64% (PC-9-5), 48.50% (PC-8-5), 94.25% (PC-7-5), 95.93% (PC-6-5), and 96.84% (PC-5-5), while the peak strain increased by 253.25% (PC-9-5), 458.13% (PC-8-5), 75.61% (PC-7-5), 149.59% (PC-6-5), and 102.44% (PC-5-5). The peak compressive strength of the PC-9-5 and PC-8-5 composite specimens is closer to that of the pure concrete specimens, whereas the PC-7-5 ~ PC-5-5 composite specimens are more akin to pure foamed cement specimens. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that when the height ratio is relatively small, the concrete in the composite specimens effectively bears the load during application, and the presence of foamed cement significantly increases the peak strain of the composite specimens. Conversely, when the height ratio is larger, the overall load-bearing structure of the composite specimens fails after the foamed cement is damaged, preventing the concrete from fully utilizing its load-bearing capacity.

With the change of peak compressive strength of foamed cement (1.56–10.49 MPa), the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS ranges from 77.67 to 83.87% of that of the pure concrete specimens, while the peak strain ranges from 128.46 to 361.38%. The experimental results indicate that variations in the strength of the foamed cement have a minimal impact on the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS, but a significant effect on the peak strain. The unique pore structure within the foamed cement provides ample compressive space during loading, resulting in a peak strain for C-FCCS that far exceeds that of the pure concrete specimens.

As shown in Table 4, the coefficient of variation for the peak strain of the PC-7-5 composite specimens (38.28%) exceeds the national standard (15%)26. As illustrated in the curve of Fig. 6g1#, the specimens with a height ratio of 30% exhibit secondary compaction characteristics, leading to greater variability in the peak strain of the composite specimens.

AE characteristics in the failure process of C-FCCS

The acoustic emission (AE) activity can predict the crack initiation threshold (CI) and the crack damage threshold (CD)41,42,43,44. Eberhardt45 noted that “cumulative AE property vs. normalized axial stress”curves can be established to characterize the crack evolution characteristics of the specimen at different stages. The crack initiation and damage thresholds can be determined by identifying the inflection points in the cumulative value curve of the acoustic emission parameters. Here, normalized axial stress refers to the ratio of the stress at any moment before the peak to the peak stress46. To simplify the analysis, this paper focuses solely on the energy parameter of acoustic emission, selecting the PC-9-1 and PC-9-5 ~ PC-5-5 composite specimens as the subjects of study. Figure 10 illustrates the relationship curves between the acoustic emission energy and their cumulative values with normalized axial stress for specimens. The cumulative energy relationship curve of the composite specimens can be roughly divided into three stages: the acoustic emission quiet period, the low-amplitude growth period, and the high-amplitude growth period47.

As shown in Fig. 10a–c, the cumulative value curves of acoustic emission energy for the PC-9-1 and PC-9-5 ~ PC-8-5 composite specimens exhibit multiple inflection points. In the early loading phase of C-FCCS, the cumulative value curve of AE energy shows both low-amplitude and high-amplitude growth periods. This is attributed to the initial failure of the foamed cement during the early loading of C-FCCS, resulting in a significant number of AE events and highly active AE signals. Some cracks in the foamed cement extend to the layering interface, where they are impeded by the concrete, leading to a reduction in large AE events and a slight decrease in AE signal intensity. As the composite specimens enter the compaction stage ii and elastic stages ii, the damaged foamed cement is gradually compacted. During this phase, the activity level of the acoustic emission signals decreases, releasing minimal energy, as depicted in Fig. 10c. The cumulative value curve of AE energy enters a secondary quiet period or low-amplitude growth period until the external load exceeds the crack initiation and damage thresholds of the concrete, at which point the acoustic emission events increase significantly once again.

As illustrated in Fig. 10d,e, the cumulative AE energy curves for the PC-7-5 ~ PC-5-5 composite specimens do not exhibit a secondary quiet period or a low-amplitude growth phase. The characteristics of these curves are akin to those of the AE characteristic parameter curves for single structural specimens21,44,46,48. A significant reduction in the cumulative AE energy of C-FCCS is observed. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the concrete did not contribute to the damage failure of C-FCCS, resulting in a substantial decrease in AE signal intensity. Furthermore, when the external load reaches the crack damage threshold of C-FCCS, the internal cracks transition into an unstable propagation phase. At this juncture, the slope of the cumulative energy curve exhibits a pronounced inflection point and begins to increase steadily, while the AE ring count and energy experience a sharp escalation, indicating a highly active phase of acoustic emission events38.

Macroscopic failure morphology of C-FCCS

Figure 11 illustrates the macroscopic failure morphology of C-FCCS, with selected pure concrete and foamed cement specimens serving as controls, as shown in Fig. 11j–l. The yellow boxes in the figure denote foamed cement, while the red curves represent macroscopic cracks. "T" indicates tensile cracks, and "S" denotes shear cracks.

As depicted in Fig. 11a–f, both the concrete and foamed cement in the PC-9-1 ~ PC-8-5 composite specimens failed. The primary mode of failure in C-FCCS was tensile, with most failures manifesting as through cracks. These through cracks initially appeared in the foamed cement and subsequently extended into the concrete as external loading continued. The initiation points of concrete failure in different specimens were predominantly located at the layered interface, which can be determined by the shape of the tensile cracks. This indicates that the tearing of foamed cemen overflow movement is responsible for the crack initiation of concrete. Singh and Gupta49,50 indicate that the failure of concrete is contingent upon the loading path, with the particle interfaces within the concrete representing a critical weakness in its strength. Compared to pure concrete specimens, the frictional forces at layered interfaces alter the stress distribution in composite concrete specimens, resulting in a reduced stress threshold required for crack initiation at the particle interfaces. Shear cracks were relatively infrequent in the composite specimens, with both their length and opening being smaller than those of the tensile cracks. Shear cracks were primarily observed at the edges of C-FCCS and at the corners of the layered interfaces, whereas tensile cracks were more concentrated towards the central region of the specimens. As shown in Fig. 11a–e, for the same height ratio, a decrease in the strength of the foamed cement resulted in cracks after concrete failure being closer to the center of the specimens. Conversely, higher strength foamed cement led to larger openings of through cracks in the regions on either side of the concrete after failure.

As illustrated in Fig. 11g–i, the failure of the PC-7-5 ~ PC-5-5 composite specimens is primarily concentrated in the foamed cement, with no significant damage observed in the concrete. Tensile cracks penetrate the foamed cement, while the integrity of the concrete remains relatively intact. This indicates that when the proportion of foamed cement is no less than 30%, the failure of the foamed cement will lead to the overall structural failure of C-FCCS. Within this range of high ratio, the mechanical behavior of C-FCCS is predominantly governed by the foamed cement. Furthermore, Fig. 11g (PC-7-5) reveals shear cracks at the edge of the layered interface in the concrete, suggesting that at this height ratio, the concrete contributes a certain degree of load-bearing capacity. In conjunction with previous research findings, the peak compressive strength of the PC-7-5 composite specimen exceeds that of the foamed cement at the same ratio by 42.3%, and the curve in Fig. 6g1# exhibits secondary compaction characteristics that lead to an increase in peak strain, as shown in Table 4. This suggests that a foamed cement proportion of 30% may represent a critical threshold influencing the mechanical behavior of C-FCCS. Specifically, below 30%, the mechanical properties of the composite specimens are dominated by the concrete, while above 30%, they are dominated by the foamed cement.

Theoretical analysis of mechanical properties of C-FCCS

The results of the aforementioned study indicate that the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS decreases progressively with an increase in the proportion of foamed cement. Zhang et al.26 noted that a smaller aspect ratio of the specimens correlates with a higher peak compressive strength. However, in this study, the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS diminishes as the proportion of concrete decreases (the aspect ratio decreases). Analyzing the failure morphology in Section "Macroscopic failure morphology of C-FCCS", it is observed that the initiation points of the through-cracks in C-FCCS predominantly occur at the layered interfaces, with the overflow effect of foamed cement being the primary cause of crack initiation in the concrete. Furthermore, the contact surfaces between sand, gravel, and cement within the concrete represent a weak link in terms of mechanical strength, as they are more prone to failure than the particles themselves. Under pure uniaxial compression conditions, the inferior contact surfaces experience failure, serving as the initiation points for through-cracks36. In pure concrete specimens, the stress required for the failure of the contact surfaces is entirely provided indirectly by the compressive stress, often necessitating a substantial compressive load to meet the failure criteria. In composite specimens, the presence of interlayer frictional forces facilitates the propagation of tensile cracks. The specimens can initiate and propagate new internal cracks under relatively low axial stress, resulting in a decrease in peak compressive strength.

Figure 12 illustrates the mechanical model for crack initiation in C-FCCS. In the Fig. 12, σ represents the axial stress of C-FCCS, τ denotes the frictional constraint stress at the layered interface, l indicates the length of C-FCCS, lfc is the length of the foamed cement in C-FCCS, lc is the length of the concrete, T represents the frictional force at the layered interface, and F is the axial force at the crack initiation point in the concrete at the layered interface.

The relationship between the friction constraint stress τ of the layered interface and the friction force T of the layered interface is:

where f is the friction coefficient of interface. The relationship between T and τ is:

The conditions for the formation of through tensile cracks in concrete under the tearing effect of foamed cement are as follows21:

In the formula, σt is the tensile strength of concrete. According to formula (1) ~ (3), available formula (4) :

From Eq. (4), it can be inferred that under conditions where the properties of concrete are similar, the axial stress required for tensile cracking of concrete is primarily related to lc and f. The axial stress necessary for tensile cracking increases with lc. Consequently, as the proportion of foamed cement increases, the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS exhibits a gradual decreasing trend. At a constant height ratio, the variation in strength of the foamed cement significantly influences the peak compressive strength of the composite specimens, primarily depending on the friction resistance coefficient f. When the proportion of foamed cement ranges from 30 to 50%, the mechanical properties of C-FCCS are predominantly governed by the foamed cement. As the aspect ratio of the foamed cement increases with the height ratio, the peak compressive strength of the composite specimens gradually diminishes26.

Figure 13 is the peak strain mechanical model of C-FCCS, and l'fc and l'c are the length of foamed cement and concrete when the composite specimen reaches the peak compressive strength. The relationship between the peak strain εc and l'fc and l'c is:

After the destruction of the foamed cement, it underwent secondary compression. Based on the morphological analysis of the failure shown in Fig. 11, it is evident that all internal bubbles of the foamed cement had dissipated by the time the composite specimen reached its peak compressive strength. Assuming the foamed cement is homogeneous and isotropic, with an internal bubble volume of V, and the volume of particles lost during the compression failure of the foamed cement being V', the following relationship can be established:

The length l'fc of the damaged foamed cement is:

Substituting Eq. (7) into Eq. (5) yields:

From Eq. (8), it can be inferred that when the mechanical properties of C-FCCS are dominated by concrete, the peak strain εc of C-FCCS is primarily related to parameters such as lfc、V and V'. The peak strain εc of C-FCCS increases with the rise in V and V'. Under the same height ratio, as the strength of the foamed cement increases, the volume of bubbles V decreases, and the volume of particles lost V' after failure of the foamed cement also diminishes, as illustrated in Fig. 11a–e. Consequently, the peak strain εc of C-FCCS exhibits a gradual increase trend with the reduction in foamed cement strength. Notably, the peak strains of PC-9-4 and PC-9-5 are approximately the same. Given the minimal differences in V and V' between the two (Fig. 11), the peak strain εc of C-FCCS is primarily influenced by the concrete strain l'c. Furthermore, the peak strain εc of C-FCCS decreases with an increase in the initial length lfc of the foamed cement; however, the peak strain of the composite specimen PC-8-5 is higher than that of PC-9-5. Analyzing in conjunction with Eq. (8), the effects of V and V' on the peak strain for PC-8-5 surpass those of lfc.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that the height ratio significantly influences the mechanical behavior of C-FCCS. The peak compressive strength of C-FCCS decreases progressively with an increase in the height ratio, while the peak strain exhibits a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing. Taking the PC-9-5 and PC-8-5 composite specimens as examples (with foamed cement proportions of 10% and 20%, respectively), it is observed that due to the substantial difference in strength between concrete and foamed cement, the foamed cement experiences cracking first during the initial loading phase. As the foamed cement undergoes compaction and overflow, its lateral deformation is constrained by the concrete to maintain consistency in the lateral deformation of C-FCCS16,51,52. Once cracks penetrate the foamed cement, the concrete fractures under the tearing action of the lateral deformation of the foamed cement. The length and number of cracks in the concrete increase with the applied external load, ultimately resulting in the formation of macroscopic cracks that traverse the concrete, as illustrated in Fig. 11a–f. This suggests that the tearing action of the foamed cement and tensile failure are the primary causes of the ultimate failure of C-FCCS. Liu’s research on composite specimens corroborates this finding21. When the foamed cement proportion is between 30 and 50%, the overall structure of C-FCCS gradually fails after the foamed cement is damaged, and the concrete layers do not fully utilize their load-bearing capacity. Integrating the results from Sections "Characteristics of the stress–strain characteristic curve of composite specimens" and "Analysis of mechanical properties of C-FCCS", it can be concluded that when the foamed cement proportion is less than 30%, the mechanical properties of C-FCCS are dominated by the concrete; conversely, when the foamed cement proportion is 30% or greater, the mechanical properties are dominated by the foamed cement. Zhao et al.24 and Gao et al.25 have noted that the peak compressive strength of composite specimens is negatively correlated with the height of weak layers and positively correlated with the height of strong layers. Cheng’s research indicates that the most significant factor affecting the composite specimens is the height ratio18, which is consistent with the findings of this study.

As the strength of foamed cement decreases (with an increase in the amount of foaming agent), the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS shows minimal variation, while the peak strain gradually increases. The internal pore structure of foamed cement can effectively absorb external loads18. The lower the strength of the foamed cement, the greater its load absorption capacity, which in turn increases the peak strain of the composite specimens. Furthermore, the strength range of the foamed cement in the experimental grouping of this study is between 1.56 MPa and 10.49 MPa (as shown in Table 3). As illustrated in Fig. 5a, pure concrete specimens within this strength range remain in the compaction phase. Depending on the findings in Section "Theoretical analysis of mechanical properties of C-FCCS", the tensile failure of C-FCCS is primarily attributed to the tearing action of the foamed cement. The axial stress required for concrete cracking is closely related to the height ratio of the concrete. Therefore, under the same height ratio, altering the strength of the foamed cement has a minimal impact on the peak compressive strength of the composite specimens. Additionally, the strength of the foamed cement influences the failure morphology of C-FCCS. As depicted in Fig. 11a–e, higher strengths of foamed cement result in larger openings of through cracks during concrete failure, with a relatively severe degree of concrete surface delamination. Chen et al.16 posits that low-strength materials in composite specimens can enhance the lateral deformation of high-strength materials, a phenomenon referred to as the “interface effect” in composite specimens52,53,54. Liu et al.19 identifies interlayer friction as one of the key factors affecting crack propagation in high-strength materials of composite specimens, which is in agreement with the findings of this study.

The findings of this study can serve as a reference for the application of composite backfilling technology in gob-side entry retaining. The design of parameters for the composite backfilling body should primarily consider the impact of height ratio on the mechanical properties of the backfilling material, while implementing measures to restrict lateral deformation of rigid layers (such as concrete). The strength of the foamed cement in this research is approximately 4.04–27.16% of the strength of concrete. There is a significant disparity in the peak compressive strength between the two materials, suggesting that subsequent experiments could broaden the strength ratio of the materials for further investigation. It is important to emphasize that the aforementioned experimental results are limited to the mechanical behavior of C-FCCS under uniaxial compression. When the layered materials and loading methods of the composite specimens are altered, it will be necessary to revise the research outcomes accordingly.

Conclusion

This study aims to investigate the mechanical properties of "rigid-flexible" structural composite specimens under uniaxial loading. The main research conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

When the foamed cement content is between 10 and 20%, the stress–strain characteristic curve of C-FCCS exhibits secondary compaction, elasticity, and plasticity stages. At a foamed cement content of 30–50%, the stress–strain curve is fundamentally similar to traditional stress–strain curves.

-

(2)

The peak compressive strength of C-FCCS shows a negative correlation with the foamed cement content and a positive correlation with the concrete content. When the foamed cement content is less than 30%, the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS is dominated by concrete; when the foamed cement content is 30% or greater, the peak compressive strength is dominated by foamed cement. The peak strain of C-FCCS at various height ratios is approximately 175.61–558.13% of that of pure concrete specimens.

-

(3)

The variation in the strength of foamed cement at the same height ratio has a minimal effect on the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS, but it significantly influences the peak strain. Under different strength of foamed cement (1.56–10.49 MPa), the peak compressive strength of C-FCCS is approximately 77.67–83.87% of that of pure concrete specimens, with peak strains ranging from 128.46 to 361.38%.

-

(4)

The macroscopic failure of C-FCCS is primarily tensile, with shear failure commonly observed at the edges and corner interfaces of the composite specimens. The height ratio is the primary factor affecting the mechanical properties and macroscopic failure morphology of C-FCCS, while the strength of the foamed cement is a secondary factor.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zha, W., Shi, H., Liu, S. & Kang, C. Surrounding rock control of gob-side entry driving with narrow coal pillar and roadway side sealing technology in Yangliu Coal Mine. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 27, 819–823 (2017).

Wang, M. et al. Stability control of overburden and coal pillars in the gob-side entry under dynamic pressure. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 170, 105490 (2023).

Han, C., Zhang, N., Ran, Z., Gao, R. & Yang, H. Superposed disturbance mechanism of sequential overlying strata collapse for gob-side entry retaining and corresponding control strategies. J. Cent. South Univ. 25, 2258–2271 (2018).

Li, X. & Liu, C. Mechanical properties and damage constitutive model of high water material at different loading rates. Adv. Eng. Mater. 20, 1701098 (2018).

Chen, D. et al. Study on stability mechanism and control techniques of surrounding rock in gob-side entry retaining with flexible formwork concrete wall. J. Cent. South Univ. 30, 2966–2982 (2023).

Kong, D., Pu, S., Cheng, Z., Wu, G. & Liu, Y. Coordinated deformation mechanism of the top coal and filling body of gob-side entry retaining in a fully mechanized caving face. Int. J. Geomech. 21, 04021030 (2021).

Guo, P., Yuan, Y., Ye, K. & Sun, D. Fracturing mechanisms and deformation characteristics of rock surrounding the gate during gob-side entry retention through roof pre-fracturing. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 148, 104927 (2021).

Cheng, Z., Li, L.-H. & Zhang, Y.-N. Laboratory investigation of the mechanical properties of coal-rock combined body. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 1947–1958 (2020).

Sun, Q., Zhao, R., Li, X. & Yuan, H. Experimental study on uniaxial compression failure characteristics and mechanical properties of composite aquiclude rock. Geofluids 2024, 6100598 (2024).

Karacan, C. Ö. Analysis of gob gas venthole production performances for strata gas control in longwall mining. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 79, 9–18 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Mechanism of rock burst occurrence in specially thick coal seam with rock parting. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49, 1953–1965 (2016).

Zhang, W. et al. Experimental and analytical investigation into the synergistic mechanism and failure characteristics of the backfill-red sandstone combination. Minerals 12, 202 (2022).

Ma, Q., Tan, Y., Liu, X., Zhao, Z. & Fan, D. Mechanical and energy characteristics of coal–rock composite sample with different height ratios: A numerical study based on particle flow code. Environ. Earth Sci 80, 309 (2021).

Yin, D., Chen, S., Jiang, N. & Sun, X. Strength characteristics of roof rock-coal composite samples with different height ratios under uniaxial loading. Arch. Min. Sci. 64(2), 307–319 (2019).

Ma, Q. et al. Experimental and numerical simulation of loading rate effects on failure and strain energy characteristics of coal-rock composite samples. J. Cent. South Univ. 28, 3207–3222 (2021).

Chen, S., Yin, D., Jiang, N., Wang, F. & Zhao, Z. Mechanical properties of oil shale-coal composite samples. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 123, 104120 (2019).

He, Y. et al. Mechanical properties and energy dissipation characteristics of Coal–Rock-Like composite materials subjected to different rock-coal strength ratios. Nat. Resour. Res. 30, 2179–2193 (2021).

Lei, S., Hao, D. & Cao, S. Study on uniaxial compression deformation and fracture development characteristics of weak interlayer coal-rock combination. Fract. Fract. 7, 731 (2023).

Liu, H., Liu, C., Yue, X. & Wang, J. Study on mechanical properties and acoustic emission characteristics of mudstone-clay composites under uniaxial compression. Eng. Geol. 332, 107478 (2024).

Pan, B., Yu, W. & Shen, W. Experimental study on energy evolution and failure characteristics of Rock–Coal–Rock combination with different height ratios. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 39, 425–435 (2021).

Gu, X. et al. Effect of interfacial angle on the mechanical behaviour and acoustic emission characteristics of coal–rock composite specimens. J. Market. Res. 21, 1933–1943 (2022).

Lu, J. et al. Mechanical properties of layered composite coal-rock subjected to true triaxial stress. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 53, 4117–4138 (2020).

Yu, Y. et al. Failure energy evolution of coal–rock combination with different inclinations. Sci. Rep. 12, 19455 (2022).

Zhao, K. et al. Synergistic deformation in a combination of cemented paste backfill and rocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 317, 125943 (2022).

Gao, H. et al. Compression failure conditions of concrete-granite combined body with different roughness interface. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33, 297–307 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Experimental study on mechanical properties of low-strength mortar-granite composite specimens. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57, 11083–11098 (2024).

Selçuk, L. & Aşma, D. Experimental investigation of the rock-concrete bi materials influence of inclined interface on strength and failure behavior. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 123, 104119 (2019).

Wang, Y., Lu, H. & Wu, J. Experimental investigation on strength and failure characteristics of cemented paste backfill-rock composite under uniaxial compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 304, 124629 (2021).

Koupouli, N., Tikou, B. & Effenguet, H. Direct shear tests on cemented paste backfill-rock wall and cemented paste backfill-backfill interfaces. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 8, 472–479 (2016).

Lu, S., Xu, J.-Y., Bai, E.-L. & Luo, X. Effect of particles with different mechanical properties on the energy dissipation properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 144, 502–515 (2017).

Zhu, W., Xu, J., Xu, J., Chen, D. & Shi, J. Pier-column backfill mining technology for controlling surface subsidence. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 96, 58–65 (2017).

Wang, X., Xie, J., Xu, J., Zhu, W. & Wang, L. Effects of coal mining height and width on overburden subsidence in longwall pier-column backfilling. Appl. Sci. 11, 3105 (2021).

Zhao, X. G., Cai, M., Wang, J. & Ma, L. K. Damage stress and acoustic emission characteristics of the Beishan granite. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 64, 258–269 (2013).

Zhao, X. G., Cai, M., Wang, J., Li, P. F. & Ma, L. K. Objective determination of crack initiation stress of brittle rocks under compression using AE measurement. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 48, 2473–2484 (2015).

Kim, J.-S., Lee, K.-S., Cho, W.-J., Choi, H.-J. & Cho, G.-C. A Comparative evaluation of stress-strain and acoustic emission methods for quantitative damage assessments of brittle rock. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 48, 495–508 (2015).

Cao, Y., Zhang, X., Sun, L., Zheng, Y. & Li, C. Mechanical properties and macro–micro failure mechanisms of granite under thermal treatment and inclination. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-energ. Geo-Resour. 11, 8 (2025).

Liu, S. & Xu, J. Effect of strain rate on the dynamic compressive mechanical behaviors of rock material subjected to high temperatures. Mech. Mater. 82, 28–38 (2015).

Chen, L., Mao, X. & Wu, P. Effect of high temperature and inclination angle on mechanical properties and fracture behavior of granite at low strain rate. Sustainability 12, 1255 (2020).

Rohde, J. & Feng, H. Analysis of the variability of unconfined compression tests of rock. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 23, 231–236 (1990).

Kahraman, S. Evaluation of simple methods for assessing the uniaxial compressive strength of rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 38, 981–994 (2001).

Li, L. et al. Progressive cracking of granite plate under uniaxial compression. Yanshilixue Yu Gongcheng Xuebao/Chinese J. Rock Mech. Eng. 21, 940–947 (2002).

Yang, S.-Q., Tian, W.-L. & Huang, Y.-H. Failure mechanical behavior of pre-holed granite specimens after elevated temperature treatment by particle flow code. Geothermics 72, 124–137 (2018).

Gautam, P. K., Verma, A. K., Jha, M. K., Sharma, P. & Singh, T. N. Effect of high temperature on physical and mechanical properties of Jalore granite. J. Appl. Geophys. 159, 460–474 (2018).

Yang, S.-Q., Huang, Y.-H., Tian, W.-L., Yin, P.-F. & Jing, H.-W. Effect of high temperature on deformation failure behavior of granite specimen containing a single fissure under uniaxial compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52, 2087–2107 (2019).

Eberhardt, E., Stead, D. & Stimpson, B. Quantifying progressive pre-peak brittle fracture damage in rock during uniaxial compression. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 36, 361–380 (1999).

Cao, Y., Xu, J., Chen, L., Wu, P. & Shaikh, F. Experimental study on granite acoustic emission and micro-fracture behavior with combined compression and shear loading: Phenomenon and mechanism. Sci. Rep. 10, 22051 (2020).

Chen, L., Wu, P., Chen, Y. & Zhang, W. Experimental study on physical-mechanical properties and fracture behaviors of saturated yellow sandstone considering coupling effect of freeze-thaw and specimen inclination. Sustainability 12, 1029 (2020).

Wu, P. et al. Experimental study on mechanical properties and microcrack fracture of coal specimens under the coupling of loading rate and compression-shear loads. Int. J. Geomech. 22, 04022028 (2022).

Chandrabhan, S. & Kumar, G. P. Biaxial behaviour of concrete and its failure mechanics under quasi-static and dynamic loading: A numerical study. Eng. Fract. Mech. 300, 109931 (2024).

Singh, C. & Gupta, P. K. Numerical analysis of failure mechanics of concrete under true dynamic triaxial loading using a four-phase meso-model. Constr. Build. Mater. 450, 138661 (2024).

Liu, J., Wang, E., Song, D., Wang, S. & Niu, Y. Effect of rock strength on failure mode and mechanical behavior of composite samples. Arab. J. Geosci. 8, 4527–4539 (2015).

Yin, D., Chen, S. J., Chen, B., Liu, X. & Ma, H. F. Strength and failure characteristics of the rock-coal combined body with single joint in coal. Geomech. Eng. 15, 1113–1124 (2018).

Zhao, Z., Wang, W., Dai, C. & Yan, J. Failure characteristics of three-body model composed of rock and coal with different strength and stiffness. Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China 24, 1538–1546 (2014).

Zhao, Z., Wang, W., Wang, L. & Dai, C. Compression–shear strength criterion of coal–rock combination model considering interface effect. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 47, 193–199 (2015).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.52404147, No.52374140, No.52304102), Youth Science and Technology Fund of China University of Mining and Technology (No.2024QN11079), Xuzhou Key Research and Development Plan (Social Development) (No.KC23314).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yue Cao: Writing and editing; Zheng Kong: Methodology; Zhijun Xu: Methodology; Yadong Zheng: Investigation; Peng Wu: Data curation; Lianhai Tai: Formal analysis; Chong Li: review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

The authors agree to the publication of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, Y., Kong, Z., Zheng, Y. et al. Experimental study on mechanical properties of composite materials of concrete and foamed cement under uniaxial compression. Sci Rep 15, 22975 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07304-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07304-y