Abstract

Ice velocity is a critical parameter in river ice monitoring, playing a vital role in analyzing ice blockages, the freeze-up process, and ice jam locations. It provides essential references for freeze-up forecasting. This study utilized UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) remote sensing imagery from December 2023, during the ice run period, combined with the Pyramidal Lucas-Kanade Optical Flow Algorithm to quantify ice velocity distribution across multiple bends during the Yellow River’s ice run period. The study identified low ice velocity cross-sections at bend apexes, where velocity decreased sharply, leading to ice floe accumulation and an increased probability of ice jams. Significant spatial variations in ice velocity within bends were observed. Curvature and constriction ratios were identified as key factors influencing ice velocity distribution. Bends with high curvature and significant constriction should be prioritized for monitoring and early warning. The study also revealed a correlation between the low ice velocity cross-section at the apex of Shisifenzi Bend and the location of the initial ice jam during the ice run period, suggesting its potential as a scientific guide for ice jam risk forecasting. These findings provide valuable insights for freeze-up forecasting and flood prevention in the Yellow River.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than half of the world’s rivers are covered by ice each winter1. River ice is a key component of hydrological systems in cold regions and has significant impacts on extreme floods, winter low flows, river transportation, hydropower generation, and ecosystems2,3. Sudden thawing during the ice flood season or freezing periods often causes river ice to block channels, resulting in flooding. Ice jam floods, common at middle to high latitude regions such as the United States, Canada, and China, pose significant threats to infrastructure and local livelihoods4,5,6. The intensification of global warming and the rise in extreme weather events have increased the uncertainty in river ice dynamics7. Consequently, efficient and adaptable real-time river ice monitoring is increasingly critical. Ice velocity, a key parameter in river ice monitoring, provides crucial insights into ice jams, freeze-up and break-up processes, and their potential locations.

The Ningxia-Inner Mongolia section of the Yellow River displays a distinct hydrodynamic pattern due to its reverse “U” shape, leading to a freeze-up and break-up sequence unlike other rivers. During freeze-up, ice forms and advances from downstream to upstream, while during break-up, it moves in the opposite direction, from upstream to downstream. This reversal increases the risk of ice-jam flooding8,9,10,11. The narrow and curved channel in Inner Mongolia makes this area prone to ice jam during freeze-up and break-up. This vulnerability is most pronounced in narrow sections and sharp bends12, where drifting ice often accumulates, causing jams and severe flood risks. Studies on river ice in Yellow River bends have primarily concentrated on numerical simulations, physical models, and mathematical models9,13. Significant progress has been made in modeling ice processes, analyzing freeze-up and break-up dynamics, understanding ice-jam formation, and characterizing ice jams14,15,16,17. These studies provide a solid theoretical foundation for understanding ice dynamics in river bends. However, effectively representing ice movement and behavior in natural bends remains challenging due to the inherent complexity of river bends, modeling limitations, and insufficient channel data. Increasing extreme weather events, large-scale freeze-ups, and channel narrowing have intensified the risks of ice-jam disasters12,18,19. Strengthening river ice monitoring, especially in bends, is therefore essential. Monitoring ice velocity is crucial for identifying ice jam risk zones and enhancing disaster prevention and control. These efforts are vital for managing ice-jam risks and advancing knowledge of complex river hydrodynamics.

Ice velocity monitoring methods have distinct advantages and limitations depending on the application scenario. In situ methods, including visual tracking, GPS monitoring, and Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers (ADCP), have unique characteristics. GPS tracking provides high accuracy by attaching sensors to ice floes for real-time velocity data collection20. However, it only measures individual ice floes and is constrained by sensor placement and retrieval, making comprehensive ice velocity field monitoring challenging. Visual tracking and manual methods are simple but rely heavily on observer expertise, leading to subjectivity, high labor costs, and limited applicability. ADCP and particle image velocimetry enhance monitoring accuracy in localized sections but are hindered by high equipment costs, operational complexity, and lengthy data processing times21,22. Satellite remote sensing, especially synthetic aperture radar (SAR), is widely used for monitoring polar ice shelves and large-scale ice flows23,24,25. However, resolution and satellite revisit time limitations make it difficult for satellite remote sensing to capture dynamic ice conditions in narrow river sections. Furthermore, orbital coverage and weather constraints reduce spatial and temporal flexibility, particularly during rapid ice movement or in complex terrain26,27. Ground-based cameras offer continuous real-time monitoring but are constrained by installation location, monitoring range, and camera height and angle, limiting their ability to comprehensively capture river system dynamics28.

In recent years, low-altitude remote sensing technology with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has gained significant attention in ice monitoring29,30. UAV-based low-altitude remote sensing offers high flexibility and adaptability for precise monitoring in complex environments. It captures high-resolution imagery for detailed river ice analysis and features low operational costs with short deployment cycles, enabling monitoring across multiple locations and time periods31. These features present a novel solution for ice velocity monitoring. Advances in computer vision techniques now enable quantitative analysis of low-altitude remote sensing imagery. Current methods have made significant strides in extracting ice-related parameters, including river ice semantic segmentation, ice type detection, ice morphology, and ice velocity, yielding promising results25,30,31,32. Combining UAV monitoring with computer vision algorithms offers a new method for dynamically visualizing ice velocity in typical Yellow River sections, especially in curved and constricted segments. This integration has great potential to enhance ice monitoring and deepen understanding of river ice dynamics.

This study employed UAV imagery with the pyramidal optical flow algorithm and Shi-Tomasi corner detection to measure ice velocities in several river segments of the Yellow River in Inner Mongolia during the drifting ice period. It quantitatively analyzed ice velocity distribution in curve sections, identifying the lowest velocity cross-sections at bend apices. The pyramidal optical flow algorithm estimated motion vectors by constructing an image pyramid, reducing resolution progressively from coarse to fine33. This method excelled in handling large-scale motion and noise, making it ideal for complex river sections with variable flow velocities. For river ice dynamics in bends, the algorithm enhanced noise resistance and efficiently processed high-resolution data, meeting the real-time and accuracy needs of UAV monitoring. Shi-Tomasi corner detection was used to identify prominent feature points, improving motion estimation accuracy and ice velocity interpretation34. Combining Shi-Tomasi corner detection with the pyramidal optical flow algorithm provided a novel method for analyzing river ice dynamics in complex systems. It offers essential data and theoretical support for studying ice transport, identifying ice-jam locations, and understanding ice movement patterns in the Yellow River. These findings aid in predicting and preventing river ice-related disasters. The study’s results can be applied to similar rivers, providing valuable insights for ice condition research and basin management.

Data and methods

Study site and data

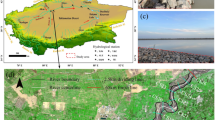

The Tuoketuo County section of the Yellow River is a critical area for addressing ice-jam disasters. The river enters this region at Baliwan Village, Tumote Right Banner, Baotou City (Fig. 1). Winters in this region are long and severe, with the river freezing in late November under intense cold air and staying frozen until early March. This section features dense river bends and multiple hydraulic structures, which limit ice transport in narrow areas and exacerbate ice jams and blockages. Large discharge freeze-up events have occurred more frequently in recent years, with a record freeze-up flow of 861 m3/s in 2021, greatly increasing ice-jam risks. The unique hydrological and climatic conditions, along with the complex channel morphology, make this area ideal for studying ice transport and ice-jam formation.

Schematic diagram of typical sections and UAV monitoring in the Tuoketuo county section of the Yellow River. The figure is taken from QGIS3.22.16 (http://qgis.org/en/site/). The four images below the overview map are captured by the DJI Mavic 3 T drone during the ice run period.

Four monitoring points were selected to study ice velocity: Minjibu Bend, Shisifenzi Bend, Guanniujie Bend, Haojiayao Bend. Among these, we monitored the bend apex downstream, the bend apex, and the bend apex upstream (Fig. 1). Monitoring points were selected to capture ice transport in complex river sections prone to drifting ice and ice jams. The Shisifenzi Bend, with its distinctive curvature and constriction ratios, exerted the strongest geometric influence on ice velocity dynamics. The Minjibu Bend featured a significant curvature ratio and moderate constriction ratio. The Guanniuju Bend, characterized by a lower curvature ratio but substantial constriction, emphasized the pivotal role of constriction in ice transport. The Haojiayao Bend, with minimal curvature and constriction ratios, served as a reference under weak geometric constraints. These monitoring locations were carefully chosen to represent diverse river morphologies and ice transport dynamics in this critical region. Monitoring was conducted from December 1 to 3, 2023, which coincided with the ice run period, a time of rapid temperature drops and frequent drifting ice events (Fig. 2). This period was optimal for capturing ice transport dynamics and ice-jam processes, ensuring reliable observations.

High-resolution videos and supplementary photographs were collected in areas with moderate ice floe density to ensure both data representativeness and measurement accuracy in measuring ice transport velocities. A DJI Mavic 3 T UAV equipped with a 4 K resolution camera (3840 × 2160) and multiple frame rate options (24/25/30/48/50/60 fps) was used to capture ice movement during intense drifting periods. The UAV operated at an altitude of 300–400 m, with test flights and adjustments ensuring image clarity and reducing weather or operational errors. To maintain flight stability, UAV operations were conducted under wind speeds not exceeding 5 m/s, ensuring stable image acquisition. Video data served as the primary source for velocity analysis, with motion trajectories calculated using feature point extraction and tracking. This approach accurately measured ice transport velocities and provided dynamic insights into ice movement and jam formation.

Methods

This study employed UAV-based low-altitude remote sensing integrated with the Pyramidal Lucas-Kanade Optical Flow Algorithm and Shi-Tomasi corner detection to measure river ice velocities during the drifting ice period in the Tuoketuo County section of the Yellow River. The integration of these algorithms offered notable advantages: Shi-Tomasi corner detection effectively extracted high-quality, rationally distributed feature points, ensuring reliable initial positions for optical flow calculations. The Pyramidal Lucas-Kanade Optical Flow Algorithm used multi-scale optimization to accurately track large displacements and complex dynamic features, offering robust technical support for analyzing river ice velocity patterns. The following section provides a detailed explanation of the calculation method.

Shi-Tomasi corner detection

Shi-Tomasi Corner Detection was used to extract reliable and trackable feature points from video frames. This method constructed a structure tensor matrix and computed its eigenvalues to quantify local gradient variations in the image (Eq. 1). The minimum eigenvalue served as the scoring criterion for corner detection (Eq. 2). The corner extraction method was validated for effectiveness and reliability through repeatability and accuracy tests in various river ice motion scenarios. The key parameters were set as follows: the maximum number of corners (maxCorners) at 100, the quality threshold (quality Level) at 0.3, and the minimum distance between corners (minDistance) at 7. These configurations ensured sparse and high-quality corner distributions, providing reliable initial points for optical flow calculations.

where: \(Z\) is the structure tensor matrix. \({I}_{x}\) and \({I}_{y}\) are the image gradients in the x and y directions, respectively. \(R\) is the corner scoring value. \(\lambda_{1} ,\lambda_{2}\) are the eigenvalues of the structure tensor matrix \(Z\).

Pyramidal Lucas-Kanade optical flow algorithm

The Pyramidal Lucas-Kanade Optical Flow Algorithm enhanced optical flow estimation through multi-scale downsampling of images (Eq. 3) to handle large pixel displacements and complex dynamic features. At the lowest resolution, optical flow was initially estimated by minimizing a residual function (Eq. 4). The estimation was refined progressively layer by layer, with the initial flow for each higher-resolution layer propagated from the results of the lower layer using Eq. 5. Finally, optical flow was computed at the original resolution, integrating multi-scale information to produce detailed and accurate flow velocity distributions (Eq. 6). To meet the requirements of feature point distribution in river ice video analysis and align UAV image resolution with the river ice motion scale, the local window size was set to winSize = (200, 200) pixels. The number of pyramid layers was chosen to align the UAV image resolution with the scale of river ice motion. Each layer’s optical flow calculation employed an iterative refinement method, terminating when the flow change was below 0.03 pixels or after 10 iterations (Eq. 7). After multiple parameter adjustments, the current configuration effectively balanced computational efficiency and feature point quality.

where: \({I}^{L}\left(x,y\right)\) is the pixel value at coordinates \(\left(x,y\right)\) in the layer at level \(L\) of the pyramid image. \({I}^{L-1}\left(x,y\right)\) is the pixel value at coordinate \(\left(x,y\right)\) in the layer at level \(L-1\) of the pyramid image (previous layer). \(x,y\) are the pixel coordinates. \(\Delta x,\Delta y\) are the offsets of neighboring pixels.

where: \(\varepsilon \left(d\right)\) is the residual (matching error). \(I\left(x,y\right)\) is the pixel value at position \(\left(x,y\right)\) in image \(I\). \(J(x+{d}_{x},y+{d}_{y})\) is the pixel value at position \((x+{d}_{x},y+{d}_{y})\) in image \(J\). \(d={(d}_{x},{d}_{y})\) is the optical flow vector (pixel displacement). \({\mu }_{x},{\mu }_{y}\) are the coordinates of the reference point. \({\omega }_{x},{\omega }_{y}\) are half the window size.

where: \({g}^{L-1}\) is the initial optical flow in the layer at level \(L-1\). \({g}^{L}\) is the initial optical flow in the layer at level \(L\). \({d}^{L}\) is the optical flow vector calculated in the layer at level \(L\).

where: \(d\) is the final optical flow vector. \({g}^{0}\) is the initial optical flow in layer 0 (the highest resolution layer). \({d}^{0}\) is the estimated optical flow in layer 0.

where: \({\eta }^{K}\) is the residual at iteration. \(k\) is the number of iterations. 0.03 is the precision threshold for optical flow changes.

Ice velocity calculation

Markers with known dimensions were imaged at various UAV flight altitudes to determine the actual pixel size. A relationship between UAV flight altitude and the actual distance corresponding to pixel points was derived (Fig. 3). The scale for various flight altitudes was computed using the derived Equation, yielding a fitting accuracy of \({R}^{2}=0.999\) confirming the reliability of the results. River ice velocity was determined based on the pixel displacement of feature points and the computed scale (Eq. 8). Velocity direction and magnitude were depicted using vector arrows and dynamically overlaid on the river background, providing an intuitive visualization of drifting ice velocity and illustrating river ice movement patterns.

where: \(\upsilon\) is the ice velocity, \(m/s\). \(\Delta x\) is the horizontal displacement in pixels (\(pixel\)). \(\Delta y\) is the vertical displacement in pixels (\(pixel\)). \(y\) is the scale factor in meters per pixel (\(m/pixel\)).

Results

Ice velocity verification

Based on the calibration of the actual distance represented by each pixel in UAV images at different flight altitudes, stable feature points with distinct characteristics were manually selected for tracking. The displacement of these points between two image frames was measured, and the ice velocity was calculated using the time interval between the frames. The ice velocity of the manually selected feature points was then compared with the velocity of the points detected automatically by the pyramidal optical flow algorithm and Shi-Tomasi corner detection for validation. The study selected 160 validation points at three flight altitudes: 300, 350, and 400 m. The results showed a mean relative error of less than 3%, confirming that UAV imagery with the Pyramidal Optical Flow algorithm achieves high-precision velocity interpretation. Linear regression analysis confirmed a strong linear correlation between interpreted and actual velocities, with \({R}^{2}=0.992\) and a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.996 (Fig. 4). Most validation points fell within the 95% confidence and prediction intervals, verifying the interpretation model’s reliability. The proposed UAV imagery-based interpretation method, combined with the Pyramidal Lucas-Kanade Optical Flow algorithm, demonstrates excellent accuracy and generalizability across various flight altitudes. It offers reliable data for analyzing river ice transport processes and has significant potential for ice flood management and ice jam risk forecasting.

Ice velocity distribution in bends

The cumulative probability density plot and statistical analysis reveal significant differences and consistent patterns in the ice velocity distribution across the four bends (Shisifenzi Bend, Minjibu Bend, Haojiayao Bend and Guanniuju Bend). The steepness of cumulative probability curves and the corresponding ice velocities indicate that the bend apex generally exhibits the most concentrated velocity distribution. Steeper curves reflect narrower velocity ranges and lower velocities, and these low-velocity concentration zones are often closely associated with the formation of initial ice jams (Fig. 5). At the Shisifenzi bend apex, ice velocities were concentrated between 0.8 and 1.0 m/s, with the 50% cumulative probability at approximately 0.9 m/s. Similarly, at the Minjibu bend apex, ice velocities ranged from 0.8 to 1.1 m/s, with the 50% cumulative probability near 1.0 m/s. In contrast, upstream of the bend apex, velocity distributions were wider, and curves were gentler, indicating greater variability and higher overall velocities. For instance, upstream of the Guanniuju bend apex, the 50% cumulative probability corresponded to 2.3 m/s, with velocities mostly between 2.2 and 2.5 m/s. The recovery of ice velocity downstream of the bend apex varies across different bends. This variation reflects the adjustment of the flow field after the bend and significantly influences the movement of ice floes and potential accumulation zones. Faster velocity recovery may facilitate the smooth movement of ice, whereas areas with slower recovery or greater velocity variations could become potential sites for ice jam formation. Therefore, analyzing the ice velocity recovery patterns in different bends is critical for predicting development of ice jams. Among these bends, downstream of the Shisifenzi apex exhibited the fastest recovery, with velocities concentrated between 1.3 and 1.5 m/s. In comparison, downstream of the Minjibu and Guanniuju bends showed slower recovery, with broader velocity distributions. Notably, at the Haojiayao Bend, ice velocities were higher and more concentrated both upstream and at the bend apex. However, downstream of the apex, velocities decreased significantly and became more dispersed, sharply contrasting with other bends. Overall, the ice velocity patterns show a clear trend: higher and more scattered velocities upstream of the bend apex, lower and more concentrated velocities at the apex, and partial recovery downstream with varying concentration levels. The following section provides a detailed analysis of the ice velocity distribution patterns across the bends.

Ice velocity distribution in the Shisifenzi Bend

The results highlighted the spatial characteristics and variation patterns of ice velocity in various sections of the Shisifenzi Bend. Upstream of the bend apex, ice velocity exhibited clear spatial distribution patterns, with faster-moving ice gradually shifting toward the concave bank (Fig. 6a). Four cross-sections, designated as I, II, III, and IV (Fig. 6b), were analyzed along the river’s flow direction. The average ice velocity measured at these cross-sections was 1.01, 1.16, 1.21, and 1.24 m/s, respectively (Fig. 6c). It was observed that all the peak points was biased towards the concave bank side (Fig. 6c). These results indicated a gradual increase in ice velocity as the ice nears the bend apex. Ice velocity was lower on both sides of the bend, especially near the banks. The ice flow showed a pattern of “lower velocity near the banks and higher velocity near the river center, closer to the concave bank” (Fig. 6c). The ice was evenly distributed across the river channel, with no significant accumulation. These results indicated a low risk of ice jamming, as there is no apparent accumulation of ice or ice blockage, and the overall flow velocity was relatively high, reducing the likelihood of ice stagnation and accumulation.

Ice velocity distribution at the Shisifenzi Bend. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex upstream. Subfigures (d), (e), and (f) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex. Subfigures (g), (h), and (i) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex downstream. The original images in panels (a), (d), (g) are captured by the DJI Mavic 3 T drone during the ice run period.

In the bend apex (Fig. 6d), ice flows showed a distinct tendency to accumulate near the concave bank. This tendency was especially pronounced in the reflow zone on the concave side of the bend apex, where large numbers of ice floes were retained. A pronounced narrowing upstream of the reflow zone further intensified ice floe aggregation and collisions. Cross-section I, within the reflow zone of the bend, was selected for ice velocity analysis (Fig. 6e). The data revealed a notable reduction in ice velocity within the reflow zone. At cross-section a, the average ice velocity was 0.81 m/s, ranging from 0.65 to 0.92 m/s (Fig. 6f). In contrast, the maximum ice velocity reached 1.44 m/s upon entering the bend apex and rose to 1.21 m/s after exiting. Unlike the upstream of the bend apex, ice accumulation was significantly observed at the bend apex, where the flow velocity also decreased significantly. This indicated that the bend apex was the most likely location for ice jamming in the four-quadrant bend.

In the bend apex downstream region (Fig. 6g), the river channel gradually widened as ice continues to flow. Ice floes accumulated in the narrowed region upstream of the bend apex were released downstream. Here, ice velocity progressively increased, causing the ice floes to disperse and be carried away effectively. As a result, the likelihood of ice jams decreased. During the recovery of ice velocity, ice floes primarily concentrated along the concave bank. Four cross-sections (I, II, III, IV) were analyzed along the river flow direction (Fig. 6h). The average ice velocity at these cross-sections was 1.19, 1.26, 1.33, and 1.37 m/s, respectively (Fig. 6i). It was observed that all the peak points were biased towards the center of the river channel (Fig. 6i). These results showed that ice velocity gradually increased as it exited the bend and moved downstream. Regions with higher ice velocity gradually shifted toward the river channel center (Fig. 6h). Overall, compared to the bend apex, ice velocity increased significantly in the bend apex downstream, with less ice accumulation and a reduced risk of ice jamming.

Ice velocity distribution in the Minjibu Bend

The results highlighted the characteristics and variation patterns of ice velocity across the Minjibu Bend. Upstream of the bend apex, ice velocity exhibited a distinct spatial distribution. The data indicated that regions with higher ice velocity gradually shifted toward the concave bank of the bend (Fig. 7a). Four cross-sections (I, II, III, and IV) were analyzed along the river’s flow direction (Fig. 7b). The average ice velocity at these cross-sections was 1.67, 1.58, 1.56, and 1.38 m/s, respectively (Fig. 7c). It was observed that all the peak points were biased towards the concave bank side (Fig. 7c). The data showed that ice velocity increased as it approached the bend apex. On both sides of the bend, particularly near the convex bank, ice velocity decreased. The distribution indicated lower ice velocity near the banks and higher velocity toward the river center and the concave bank (Fig. 7c). Ice was distributed uniformly across the river channel without significant accumulation.

Ice velocity distribution at the Minjibu Bend. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex upstream. Subfigures (d), (e), and (f) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex. Subfigures (g), (h), and (i) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex downstream. The original images in panels (a), (d), (g) are captured by the DJI Mavic 3 T drone during the ice run period.

At the bend apex (Fig. 7d), ice floes showed a distinct tendency to accumulate along the concave bank, becoming denser near the apex. Ice velocity dropped to its lowest point near the apex. Data from cross-section I at the bend apex (Fig. 7e) showed that this section had the lowest ice velocity. The average ice velocity was 0.84 m/s, ranging from 0.73 to 0.93 m/s (Fig. 7f). Ice velocity was higher upon entering the bend apex but dropped significantly in the narrow section, where dense ice floes increased the risk of ice jams. As ice moved away from the apex, velocity gradually recovered, and floes dispersed across the river channel.

In the bend apex downstream region, as ice flowed downstream, the river channel widened (Fig. 7g). Ice floes accumulated in the narrow section were released downstream, where unrestricted flow allowed them to disperse effectively across the river channel (Fig. 7h). Four cross-sections (I, II, III, and IV) were analyzed, revealing average ice velocities of 1.09, 1.19, 1.05, and 1.01 m/s, respectively (Fig. 7i).

Overall, the ice velocity in the Minjibu Bend was predominantly directed toward the concave bank. Downstream of the bend apex, the flow direction gradually shifted toward the center of the channel. At the apex, ice continuously accumulated on the concave bank. The flow velocity reached its lowest point in the constricted section at the bend apex, dropping to 0.84 m/s. Compared to the upstream and downstream areas, the ice jam risk remained highest at the bend apex. This distribution was similar to the one observed at the Shisifenzi Bend, though ice accumulation was more intense there, with even lower ice velocities at the narrowest sections. This reflected the influence of ice velocity on the degree of ice accumulation.

Ice velocity distribution in the Guanniuju Bend

The results highlighted the characteristics and variation patterns of ice velocity across the Guanniuju Bend. Upstream of the bend apex, ice velocity showed distinct spatial patterns. The data indicated that higher ice velocity regions were concentrated along the concave bank (Fig. 8a), with an average velocity of 2.39 m/s. In contrast, the convex bank had a lower average velocity of 2.14 m/s. Three cross-sections (I, II, and III) were analyzed along the river’s flow direction (Fig. 8b). Average velocities near the concave bank were 2.29, 2.21, and 2.36 m/s, respectively (Fig. 8c), while the convex bank had lower averages of 2.19, 2.10, and 2.10 m/s. It was observed that the peak velocity near the left bank of the river was much lower than that near the right bank, with higher ice velocity regions located closer to the left bank of the river (Fig. 8c). Significant acceleration was observed near the concave bank as the flow approached the bend apex, a pattern absent near the convex bank. The mid-channel bar created new boundaries, leading to significantly lower velocities near the bar and along both banks (Fig. 8a). Ice was evenly distributed across the river channel, with no signs of floe accumulation. Overall, ice velocity was higher along the concave bank and significantly lower near the mid-channel bar.

Ice velocity distribution at the Guanniuju Bend. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex upstream. Subfigures (d), (e), and (f) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex. Subfigures (g), (h), and (i) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex downstream. The original images in panels (a), (d), (g) are captured by the DJI Mavic 3 T drone during the ice run period.

At the bend apex (Fig. 8d), ice floes accumulated along the concave bank. Four cross-sections (I, II, III, and IV) showed average velocities near the concave bank of 1.66, 1.60, 1.68, and 1.78 m/s, respectively (Fig. 8e). Ice velocity decreased gradually as the flow entered the narrow section at the bend apex, reaching a low of 1.60 m/s. Upon exiting the narrow section, velocity increased to 1.78 m/s as floes dispersed with the expanding flow space (Fig. 8f).

In the bend apex downstream region (Fig. 8g), the river channel widened significantly as ice flowed downstream. Floes from the narrow section were released, causing a gradual increase in velocity. The flow became unconstrained, with higher velocity concentrated near the concave bank and the floes dispersed across the channel (Fig. 8h). Four cross-sections (I, II, and III); showed average velocities of 1.80, 1.74, and 1.78 m/s (Fig. 8i). Velocity remained stable at approximately 1.77 m/s. It was observed that due to the narrowing of the river channel, the degree of ice accumulation significantly increased, the ice velocity decreased, and the risk of ice jams rose.

Throughout the Guanniuju Bend, ice velocity consistently shifted toward the concave bank, with significant accumulation upstream and near the bend apex. Downstream of the apex, floes were more dispersed. Velocity patterns indicated higher speeds upstream of the bend apex. Upon entering the narrow section at the apex, velocity dropped to 1.60 m/s, increasing the risk of ice jams. In the downstream region, expanding flow space increased velocity and dispersed floes, reducing the risk of jams. These results revealed dynamic changes in ice velocity across the Guanniuju Bend.

Ice velocity distribution in the Haojiayao Bend

The results highlighted the characteristics and variation patterns of ice velocity in the Haojiayao Bend. Upstream of the bend apex, ice velocity showed distinct spatial variations. Data indicated that high-velocity regions shifted from the convex bank to the concave bank (Fig. 9a). Four cross-sections (I, II, III, and IV) were examined along the river’s flow direction (Fig. 9b), with average velocities of 1.89, 1.78, 1.76, and 1.68 m/s, respectively (Fig. 9c). As the flow approached the bend apex, velocity decreased, and floes became denser, concentrating near the concave bank. Ice velocity showed lower speeds near both banks, with high-velocity regions shifted from the convex bank to the concave bank.

Ice velocity distribution at the Haojiayao Bend. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex upstream. Subfigures (d), (e), and (f) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex. Subfigures (g), (h), and (i) respectively show the spatial distribution of ice velocity, scatter plots of ice velocity in the pixel coordinate system, and the variation of ice velocity along vertical cross-sections of the bend-apex downstream. The original images in panels (a), (d), (g) are captured by the DJI Mavic 3 T drone during the ice run period.

At the bend apex (Fig. 9d), floes accumulated along the concave bank and became denser near the apex, where velocity reached its lowest point. Data from cross-section I (Fig. 9e) indicated the lowest velocity, with an average of 1.66 m/s, a maximum of 1.73 m/s, and a minimum of 1.27 m/s (Fig. 9f). Ice velocity was higher upon entering the bend apex, peaking at 2.33 m/s. Near the apex, velocity decreased to 1.73 m/s as floes became densely distributed.

Downstream of the apex, velocity gradually decreased to 0.89 m/s. The reduction in velocity was especially pronounced upon entering the constricted section immediately downstream of the bend apex. Further downstream, as ice flowed, the river channel widened. Floes released from the narrow section led to a gradual decrease in velocity (Fig. 9g). Unconstrained flow allowed floes to disperse across the channel, shifting toward the convex bank (Fig. 9h). Four cross-sections (I, II, III, and IV) showed average velocities of 1.27, 1.22, 1.22, and 1.16 m/s (Fig. 9i). As the flow exited the bend, velocity gradually decreased, but dispersed floes reduced the risk of jams.

Across the Haojiayao Bend, ice velocity consistently shifted toward the concave bank upstream of the apex. Floes accumulated along the concave bank upstream, while downstream they shifted toward the convex bank and became more dispersed. Velocity decreased near the apex, reaching a low of 1.66 m/s, but remained relatively high upstream and at the apex and reduced the risk of jams. In the downstream region, velocity decreased further, and floes dispersed more widely. These results revealed dynamic variations in ice velocity across the Haojiayao Bend.

Overall, ice flow velocity in the Haojiayao Bend was directed towards the concave bank from upstream to the apex of the bend, with ice continuously accumulating along the concave bank. Downstream of the apex, the flow direction shifted toward the convex bank, and the ice became more dispersed. The velocity distribution showed a clear reduction near the bend apex, where the velocity dropped to a minimum of 1.66 m/s. As the flow entered the downstream narrow section, the channel narrowed further, causing a further decrease in velocity and an increased risk of ice jams.

Discussion

Relationship between ice velocity and channel condition

The analysis of four representative river bends (Shisifenzi, Minjibu, Haojiayao, and Guanniuju) shows that curvature, constriction ratios, channel width, and boundary conditions significantly impact ice velocity distribution, with clear differences between the bends (Fig. 10 and Table 1). In this study, curvature refers to the maximum curvature value along the fitted river centerline within each bend. High curvature causes flow to deviate toward the concave bank, particularly in the Shisifenzi Bend, where a curvature of 0.0015 reduces ice velocity to as low as 0.81 m/s, resulting in ice accumulation in the low-velocity cross-section. In comparison, the Minjibu Bend, with a curvature of 0.0012, also shows flow deviation but forms a smaller low-velocity zone, where the lowest ice velocity is approximately 0.84 m/s. The Haojiayao and Guanniuju Bends, with much lower curvatures of 0.0004 and 0.0002, respectively, exhibit stable flow and uniform ice velocity, with no significant low-velocity zone. Constriction ratios further influence ice velocity. In this study, the constriction ratio is defined as the ratio of the maximum to minimum channel width along the flow direction, indicating the degree of channel narrowing. In the Guanniuju Bend, a constriction ratio of 2.5 reduces velocity to 1.60 m/s despite its low curvature, forming a concentrated low-velocity zone. Similarly, in the Shisifenzi Bend, a constriction ratio of 1.87, combined with high curvature, further reduces flow velocity at the bend apex. In contrast, the Haojiayao Bend, without obvious constriction, maintains higher ice velocities, lowering the risk of ice blockage. The narrowest channel width intensifies constriction effects. In the Shisifenzi Bend, where the channel narrows to 77 m, the combination of high curvature and constriction produces a prominent low-velocity zone. In the Guanniuju Bend, a channel width of 81 m and extreme constriction also significantly reduce ice velocity. Conversely, the Haojiayao Bend, with a wider channel width of 136 m, experiences fewer flow constraints and maintains the most uniform ice velocity distribution. Boundary conditions, such as mid-channel bars and shore ice growth, further affect ice velocity distribution. For instance, the sandbar in the Guanniuju Bend creates a hydrodynamic boundary, reducing local velocities and expanding the low-velocity zone. Similarly, the continued growth of shore ice constrains water flow, increasing channel constriction and the risk of ice accumulation. Overall, ice velocity is influenced by flow deviation due to curvature, velocity reduction caused by constriction ratios and narrowing channels, and further constraints from mid-channel bars and shore ice growth. These effects are most evident in the Shisifenzi Bend, where high curvature and significant constriction produce notable low-velocity cross-section. In contrast, the Haojiayao Bend, with low curvature and no constriction, maintains uniform ice velocity and the lowest risk of ice blockage. This analysis offers valuable insights for river channel management and ice jam risk assessment.

Relationship between ice velocity and initial ice jam location

At the Shisifenzi Bend, the combined effects of high curvature and significant constriction ratios result in a notable reduction in ice velocity at the bend apex, reaching as low as 0.81 m/s, which creates a distinct low-velocity cross-section. Monitoring shows that this low-velocity cross-section closely aligns with the initial ice jam location: drifting ice accumulates and stagnates at the bend apex, gradually forming an initial ice jam that may evolve into a blockage point (Fig. 11). This indicates that hydrodynamic disturbances caused by channel constriction and high curvature are the main factors behind reduced ice velocity and ice accumulation, with the low ice velocity cross-section serving as a key indicator for identifying initial ice jam location. However, the formation of such locations is influenced by additional factors, including flow discharge, water temperature, and ice floe density, meaning that the spatial distribution of low-velocity cross-section cannot fully predict the precise trigger points of ice blockage3,4,35,36. In practical applications, further validation of the relationship between low-velocity zones and initial ice jam locations is necessary, integrating field monitoring data and numerical simulations. Moreover, hydrodynamic and thermodynamic conditions must be considered to enhance the accuracy of early warning systems for ice jam risks. This study highlights that low-velocity zones not only reflect hydrodynamic disturbances but also provide a valuable reference for identifying initial ice jam locations. These findings have practical implications for ice jam risk warnings, particularly in river segments with high curvature and significant constriction, which should be prioritized as key areas for monitoring and early warning systems.

Research limitations analysis

This study used UAV monitoring technology combined with the Pyramidal Optical Flow algorithm to interpret ice velocity in several bends of the Yellow River, revealing spatial patterns of ice transport and high-risk ice jam locations. However, the data collection was primarily focused on specific drifting ice periods and pre-freeze stages, which limits a comprehensive understanding of long-term river ice changes across the entire winter or multiple years. Additionally, the spatial coverage of UAV monitoring is restricted, leaving some river segments inadequately observed and potentially omitting larger-scale ice transport patterns. The study also did not fully account for the influence of underwater topography and sub-ice water flow on ice motion, factors that could play a significant role in ice transport and ice jam formation. These limitations may affect the broader applicability of the results. Future research should expand temporal and spatial scales to include longer monitoring periods and larger study areas while integrating hydrological, topographical, and meteorological parameters to improve comprehensiveness and reliability. Although the Pyramidal Optical Flow algorithm combined with Shi-Tomasi corner detection has shown high accuracy and adaptability in this study, its performance may be influenced under complex river conditions, particularly when dealing with complex and nonlinear motions. When ice floes exhibit strong rotational motion or irregular shapes, the algorithm may fail to capture the overall motion trend, leading to errors in flow velocity estimates and a decline in interpretation accuracy. However, in this study, considering that the impact of such errors on river velocity distribution patterns is minimal, and in order to simplify the algorithm, we have not taken into account the effect of irregular motion of ice floes on the algorithm.

Conclusion

This study used UAV remote sensing imagery from December 2023, ice run period. Combined with the Pyramidal Lucas-Kanade Optical Flow Algorithm and Shi-Tomasi corner detection, it analyzed ice velocity distribution across river bends.

-

(1)

Ice velocity varied significantly across bend regions. At the bend apex upstream, velocities were relatively high, and ice floes shifted toward the concave bank. At the apex, velocity dropped sharply, forming a low ice velocity cross-section with a narrow range and concentrated distribution, causing ice floe accumulation. At the bend apex downstream, as the channel widened, ice floes dispersed, and ice jam risks decreased. These results highlight the critical role of bend geometry in ice transport, especially the significant velocity reduction at the apex.

-

(2)

Curvature and Constriction Ratios had a significant impact on ice velocity distribution. Bends with high curvature and strong constriction require priority monitoring and early warning. For example, the Shisifenzi Bend, with the high curvature (0.0015) and a notable constriction ratio (1.87), displayed a marked low ice velocity cross-section at the apex, where velocity fell to 0.81 m/s, making it the area with the greatest ice jam risk. In contrast, the Haojiayao Bend, with the lowest curvature (0.0004) and no obvious constriction, had uniform velocity distribution without a significant low ice velocity cross-section, resulting in minimal ice jam risk. Similarly, the Guanniuju Bend, despite its low curvature (0.0002), showed strong constriction (2.5), creating a notable low ice velocity cross-section at the apex with a minimum velocity of 1.60 m/s.

Monitoring results showed that during the ice run period, the low ice velocity cross-section at the apex of Shisifenzi Bend corresponds to the initial ice jam location, providing a scientific basis for ice jam risk forecasting. However, this study did not account for hydrodynamic and thermodynamic factors. Further research is needed to explore these factors and validate the findings in other cold-region rivers, particularly those with narrow and curved sections prone to ice accumulation.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article. The data can be provided by the author Zhongshu Xue upon request (zhongshuxue@emails.imau.edu.cn).

References

Yang, X., Pavelsky, T. M. & Allen, G. H. The past and future of global river ice. Nature 577, 69–73 (2020).

Brooks, R. N., Prowse, T. D. & O’Connell, I. J. Quantifying Northern Hemisphere freshwater ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1128–1131 (2013).

Beltaos, S. & Prowse, T. River-ice hydrology in a shrinking cryosphere. Hydrol. Process. 23, 122–144 (2009).

De Munck, S., Gauthier, Y., Bernier, M., Chokmani, K. & Légaré, S. River predisposition to ice jams: a simplified geospatial model. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 1033–1045 (2017).

Goldberg, M. D. et al. Mapping, monitoring, and prediction of floods due to ice jam and snowmelt with operational weather satellites. Remote Sens. 12, 1865 (2020).

Liu, M. et al. Hazard assessment and prediction of ice-jam flooding for a river regulated by reservoirs using an integrated probabilistic modelling approach. J. Hydrol. 615, 128611 (2022).

Fallah, B. & Rostami, M. Exploring the impact of the recent global warming on extreme weather events in Central Asia using the counterfactual climate data ATTRICI v1.1. Clim. Change 177, 80 (2024).

Fu, C., Popescu, I., Wang, C., Mynett, A. E. & Zhang, F. Challenges in modelling river flow and ice regime on the Ningxia-Inner Mongolia reach of the Yellow River, China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 1225–1237 (2014).

Li, C., Ji, X. F., Zhao, S. X. & Shen, H. T. Numerical simulation of ice transport and accumulation process in Toudaoguai reach of the Yellow River. J. Hydraul. Eng. 54, 474–485 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. Simulation of ice processes in the Inner Mongolia reach of the yellow river1. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4110454 (2022).

Wang, W., Zhang, Y. & Tang, Q. Impact assessment of climate change and human activities on streamflow signatures in the Yellow River Basin using the Budyko hypothesis and derived differential equation. J. Hydrol. 591, 125460 (2020).

Zhao, S.-X. et al. Freeze-up ice jam formation in the river bend, a case study on the Inner Mongolia reach of yellow river. Crystals 11, 631 (2021).

Sui, J., Karney, B. W., Sun, Z. & Wang, D. Field investigation of frazil jam evolution: A case study. J. Hydraul. Eng. 128, 781–787 (2002).

Gao, G. M., Deng, Y., Tian, Z. Z., Li, S. X. & Zhang, B. S. Brief introduction and prospect of recent ice research in the yellow river. Yellow River 41, 77–81+108 (2019).

Guo, X. L. et al. Progress and trend in the study of river ice. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. 53, 655–671 (2021).

Yang, K. L. Advances of ice hydraulics, ice regime observation and forecasting in rivers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 49, 81–91 (2018).

Luo, H. et al. An analytical study for predicting incipient motion velocity of sediments under ice cover. Sci. Rep. 15, 1912 (2025).

Chen, D. L., Lu, L. & Yan, Y. Q. Advantages and disadvantages of freeze-up with large discharge in the Inner Mongolia reach of Yellow River. J. China Hydrol. 41, 7–12 (2021).

Yang, Z., Mou, X., Ji, H., Liang, Z. & Zhang, J. Effects of freeze–thaw on bank soil mechanical properties and bank stability. Sci. Rep. 14, 9808 (2024).

Song, C. S., Zhu, X. Y., Han, H. W., Lin, L. B. & Yao, Z. The influence of riverway characteristics on the generation and dissipation of ice dam in the upper reaches of Heilongjiang River. J. Hydraul. Eng. 51, 1256–1266 (2020).

Chave, R. A. J., Lemon, D. D., Fissel, D. B., Dupuis, L. & Dumont, S. Real-time measurements of ice draft and velocity in the St. Lawrence River. In: Oceans ’04 MTS/IEEE Techno-Ocean ’04 (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37600) 3 1629–1633 (IEEE, Kobe, Japan, 2004).

Daigle, A., Bérubé, F., Bergeron, N. & Matte, P. A methodology based on particle image velocimetry for river ice velocity measurement. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 89, 36–47 (2013).

Jawak, S. D. et al. Seasonal comparison of velocity of the Eastern tributary glaciers, Amery ice shelf, Antarctica, using SAR offset tracking. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 5, 595–600 (2019).

Lee, H., Seo, H., Han, H., Ju, H. & Lee, J. Velocity anomaly of Campbell Glacier, East Antarctica, observed by double-differential interferometric SAR and ice penetrating radar. Remote Sens. 13, 2691 (2021).

Lee, S., Kim, S., An, H. & Han, H. Ice velocity variations of the cook ice shelf, East Antarctica, from 2017 to 2022 from Sentinel-1 SAR time-series offset tracking. Remote Sens. 15, 3079 (2023).

Kääb, A. & Prowse, T. Cold-regions river flow observed from space: cold-regions river flow from space. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, 8 (2011).

Kääb, A., Altena, B. & Mascaro, J. River-ice and water velocities using the Planet optical cubesat constellation. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 4233–4247 (2019).

Li, C. et al. A survey method for drift ice characteristics of the yellow river based on shore-based oblique images. Water 15, 2923 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. ICENET: A semantic segmentation deep network for river ice by fusing positional and channel-wise attentive features. Remote Sens. 12, 221 (2020).

Ansari, S., Rennie, C. D., Clark, S. P. & Seidou, O. IceMaskNet: River ice detection and characterization using deep learning algorithms applied to aerial photography. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 189, 103324 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. ICENETv2: A fine-grained river ice semantic segmentation network based on UAV images. Remote Sens. 13, 633 (2021).

Błotnicki, J., Jarzembowski, P., Gruszczyński, M. & Popczyk, M. The use of UAV for measuring the morphology of ice cover on the surface of a river: A case study of the low head dam and fishway inlet area in the Odra river. Water 15, 3972 (2023).

Bouguet, J.-Y. Pyramidal Implementation of the Lucas Kanade Feature Tracker Description of the algorithm. (2001).

Jianbo Shi & Tomasi. Good features to track. In: Proceedings of IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition CVPR-94 593–600 (IEEE Comput. Soc. Press, Seattle, WA, USA). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.1994.323794. (1994).

Shen, H. T. & Liu, L. Shokotsu River ice jam formation. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 37, 35–49 (2003).

Beltaos, S. & Prowse, T. D. Climate impacts on extreme ice-jam events in Canadian rivers. Hydrol. Sci. J. 46, 157–181 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Joint Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52379014), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U23A2012), Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Science and Technology Leading Talent Team (2022LJRC0007), Inner Mongolia Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023QN05026), and the Excellent Doctoral Talent Program of Inner Mongolia Agricultural University (NDYB2022-28).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.S.X: Writing, Investigation, Validation, Conceptualization; H.L.J: Writing-review & editing, Supervision; H.C.L & B.L: Writing, Investigation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, Z., Ji, H., Luo, H. et al. Ice velocity in the Yellow River bends using unmanned aerial vehicle imagery. Sci Rep 15, 22956 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07321-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07321-x