Abstract

This study successfully developed Cu-Mn supported catalysts on fly ash geopolymer for the oxidative removal of toluene. The surface characteristics and catalytic performance of catalysts were systematically investigated in this paper. It was found that the Cu/Mn ratio plays a crucial role in determining the catalysts’ performance, with the Geo-3 catalyst showing the highest toluene conversion rate of 90% at 296 ℃. The catalyst also exhibited the lowest activation energy of 123.0 kJ/mol, indicating its superior catalytic efficiency. The findings not only contribute to the development of cost-effective and efficient catalysts for VOCs degradation but also provide valuable insights into the influence of the Cu/Mn ratio on the catalytic properties of geopolymer-supported Cu-Mn catalysts. This research offers a promising approach for the abatement of VOCs in industrial emissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the continuous development of industrialization and urbanization worldwide, the excessive emission of organic volatile compounds (VOCs) has become one of the important problems on the road to green and sustainable development today1,2. It has been reported that alkanes and aromatics have become the two main types of harmful high-concentration volatile organic compounds in urban atmosphere3. As a representative aromatic substance, toluene is one of the important components of VOCs, widely used in solvents and gasoline additives. In a short period, toluene can induce dizziness, nausea, skin and mucous membrane damage, chronic poisoning, and a series of diseases4,5. Therefore, how to degrade or transform this pollutant has become an unavoidable problem for people6,7,8.

Traditional VOCs removal technologies include adsorption, condensation, membrane separation, and high-temperature incineration9,10,11. However, catalytic oxidation VOCs have attracted wide attention due to their advantages such as low cost, high efficiency, and non-toxic products1. In fact, the is a gas-solid phase reaction occurring on the surface of the catalyst12. The reaction process can be carried out at a lower temperature and is finally completely decomposed into water and carbon dioxide without any by-products13. In past studies, a series of catalysts have been applied to the catalytic oxidation of VOCs, such as precious metal catalysts, transition metal oxide catalysts, metal-organic framework (MOFs) catalysts, and composite metal oxide catalysts. Among them, the precious metal catalyst shows better catalytic activity, but it is easy to be poisoned and deactivated. In addition, their higher cost and lower reserve capacity make them less attractive14. Therefore, researchers have turned their attention to catalysts with high efficiency, low cost, and good repeatability15.

Transition metal oxide catalysts, such as CuO, have slightly lower catalytic activity than precious metals but offer advantages like lower cost and high stability. CuMn catalysts, particularly those with high Cu-O-Mn activity, show promise in VOC degradation. Wang et al. Found that the Cu-O-Mn site in CuMnOx catalyst has a high activity, providing new insights into the active site on CuMnOx catalyst16. It is believed that Cu-BTC@biochar has excellent adsorption performance for toluene at medium and high temperatures of 60 °C and 150 °C and shows good temperature resistance2. Yang, et al.17 reported that a CuOx composite with good dispersion and excellent reducibility at low temperatures was synthesized by maintaining the original form of Cu-1,3,5-phenyl tricarboxylate (Cu-BTC), which was a MOF compound composed of copper ions and 1,3,5-phenyltrimeric acid (BTC) ligands. Moreover, geopolymer is an inorganic polymer formed by mineral condensation reaction of silicon aluminum inorganic raw materials, with a three-dimensional network structure18. Among them, porous geopolymer spheres have many advantages19such as good adsorption performance, stable chemical properties, etc. Therefore, they have wide applications in adsorption purification, catalytic degradation, catalyst support, and other fields20.

Fly ash is a kind of powder waste collected from the flue gas after coal combustion, containing a large amount of SiO2 as well as metal oxides such as Fe2O3 and Al2O3. If not properly handled, it can cause significant environmental damage to the atmosphere and water, thereby affecting human health. Currently, fly ash is mainly used as admixture for concrete, which is a promising treatment method. However, due to its content of SiO2, which can be activated with alkali to form geopolymer and used as a fine catalyst support, and the metal substances can act as catalyst particles. Therefore, many research focused on the preparation of cost-effective catalysts from fly ash in recent years. However, the preparation conditions and catalyst loading methods can greatly affect the catalytic performance of, fly ash based geopolymer catalyst .

Thus, this paper mainly investigated the preparation of fly ash porous geopolymer based catalyst by a new process and the optimum preparation conditions were investigated. The effect of preparation method on the surface characteristics and catalytic activity of catalysts were thoroughly investigated by characterization and experimental observations. This paper aims to provide more pathways for the preparation of high-efficiency and low-cost transition metal oxide catalysts, and expand their applications in the catalytic degradation of VOCs.

This paper aims to provide more pathways for the preparation of high-efficiency and low-cost transition metal oxide catalysts and expand their applications in the catalytic degradation of VOCs. Specifically, the proposed approach includes: (1) the use of industrial waste fly ash as a sustainable aluminosilicate source for geopolymer formation, reducing raw material cost; (2) the development of a one-step hydrothermal–calcination process to in-situ load Cu and Mn oxides on porous geopolymer microspheres, ensuring uniform dispersion and strong metal–support interaction; and (3) the systematic investigation of the effect of Cu/Mn molar ratios on structural, textural, and redox properties of the catalysts to optimize catalytic performance. These strategies collectively represent a scalable and economical route toward the design of VOC catalysts with tunable activity and structure–property correlation.

The use of porous spherical geopolymer (Geo) as a catalyst support offers several advantages for the oxidative removal of toluene. First, the spherical morphology provides a high packing density and uniform flow distribution in fixed-bed reactors, which enhances contact efficiency between the gas-phase reactants and active sites. Second, the hierarchical pore structure facilitates rapid mass transfer of toluene molecules and reaction intermediates, thereby reducing diffusion limitations and improving catalytic turnover. Third, the geopolymer matrix, rich in SiO2 and Al2O3 from fly ash, exhibits strong thermal stability and excellent mechanical integrity under reaction conditions. Additionally, the porous surface allows effective dispersion and anchoring of metal oxides (e.g., Cu, Mn), promoting strong metal–support interaction and enhanced redox activity. These structural and compositional features make Geo a highly suitable support material for VOC catalytic oxidation.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

The fly ash (FA) used in this study was obtained from the Kanas Power Plant inXinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. The FA consisted of SiO2 (45.9wt%), Al2O3 (19.03wt%), CaO (16.39wt%), SO3 (6.01wt%), Fe2O3 (5.65wt%), K2O (2.07wt%), MgO (2.02wt%), and Na2O (0.954wt%). C6H3(CO2H)3 was obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Cu(NO3)2·3H2O was obtained from Shanghai Kechang Fine Chemical Products Company. Mn(NO3)2 was obtained from Tianjin Zhiyuan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.

Preparation methods

Preparation of porous spherical geopolymers (Geo)

The synthesis of porous spherical geopolymers was based on the research of Li, et al.21Novais, et al.22and Xu and Van Deventer23with some modifications. Firstly, 10.00 g fly ash and 2.00 g liquid sodium silicate were mixed for 2 h and completion of mixing, the mixture was dropped into a 75 °C water bath using a syringe, obtaining micro-spheres of the same size. Then, micro-spheres were washed with anhydrous ethanol. After calcination at 300 °C for 1 h, the sample was washed 3 times with distilled water. Then it was dried at 85 °C for 12 h, obtaining the porous spherical geopolymer, which was marked as Geo. The final drying step could ensure that the product is free of moisture, which would negatively impact the stability and mechanical properties of the geopolymer.The liquid sodium silicate used in this experiment had a SiO2/Na2O modulus of 3.3 and a solid content of approximately 35 wt%. This composition was selected to ensure sufficient silicate availability for geopolymer network formation and to maintain suitable viscosity for uniform mixing with fly ash.

To address the concern regarding the potential impact of skipping the drying step prior to calcination, it should be clarified that an intermediate pre-drying process was performed before calcination. After microsphere formation in the 75 °C water bath, the samples were initially rinsed with anhydrous ethanol and then air-dried at room temperature (~ 25 °C) for approximately 6 h to remove surface and pore water. This step ensured the removal of residual moisture and minimized structural cracking during subsequent thermal treatment. Following this, the samples were subjected to calcination at 300 °C for 1 h to enhance the mechanical stability and pore structure of the geopolymer framework.

This pre-drying step was essential to prevent the disruption of the geopolymerization process and to ensure that the microspheres maintained their integrity during calcination. Skipping this step could indeed hinder polycondensation and lead to pore collapse or uncontrolled shrinkage due to rapid water evaporation. The revised preparation route thus includes:

The synthesis of Geo based catalysts were based on the report of Odularu24 and Cotin, et al.25with some modifications.In the experiment, three groups of hydrothermal precursors were configured according to Table 1, with copper to manganese molar ratios of 5:1, 5:2, and 5:3, respectively. The precursor solution was prepared by mixing copper nitrate and manganese nitrate solutions in these specified molar ratios, as shown in Table 1. The precursor solution was prepared by mixing copper nitrate and manganese nitrate solution with different ratios as shown in Table 1, adding 0.86 g solution as an adjuvant, and stirring evenly. Then, the Geo of equal mass were added into the three groups of precursor liquid in the reaction kettle respectively and were placed in the oven at 120 ℃ for 10 h. Then, the products were extracted and washed three times with distilled water and anhydrous ethanol respectively, and then dried in an oven at 80 ℃ for 12 h. After drying, the Geo were roasted in a Muffle furnace at 500 ℃ for 1 h. The obtained catalysts were labeled as Geo-1, Geo-2 and Geo-3, respectively. The schematic diagram of the preparation of Geo based catalysts and its VOCs degradation path were shown in Fig. 1.The addition of polyphthalic acid solution served as a complexing and dispersing agent during the hydrothermal synthesis process. Its role was twofold: first, to improve the dispersion of metal ions in the precursor solution by forming coordination complexes with Cu2+ and Mn2+, which prevents premature precipitation and ensures uniform loading onto the geopolymer surface; second, to enhance the affinity between the metal precursors and the porous geopolymer framework, thereby promoting the anchoring and in-situ formation of active metal oxide phases during the subsequent thermal treatment. This ultimately contributes to a more homogeneous distribution of Cu-Mn species and improved catalytic performance of the resulting materials.

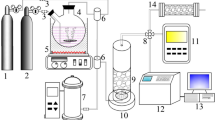

The surface area of the catalysts was measured using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. Meanwhile, the pore volume and pore size distribution were determined using the non-local density functional theory (NLDFT) approach. All measurements were conducted with an automatic physical adsorption instrument (Micromeritics ASAP 2460) based on nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms at 77 K. The gas chromatograph used to analyze the residual toluene concentration during the catalytic performance tests was a GC9790-II (Zhejiang Fuli Analytical Instruments Co., China), and the gas mixing was performed using a GX-300 A nitrogen-hydrogen-air all-in-one machine (Beijing Zhongxing Huili Technology Development Co., China).

Catalytic degradation performance test methods

Catalyst performance test method

The inner diameter of the quartz reaction tube used for the catalytic performance test was 10 mm. The catalyst was crushed and sieved, and 0.30 g of a 40–60 mesh sample was taken for the catalytic test. The required quartz sand was weighed according to the mass ratio of catalyst to quartz sand of 1:4, and the two were mixed thoroughly and transferred to the fixed bed of the quartz reaction tube. A K-type thermocouple was inserted into the reaction tube to measure the actual temperature of the bed during the reaction, and the temperature of the reaction tube was controlled by a programmable thermostat. The reaction gas was prepared using nitrogen bubbling method, with a toluene concentration of 800 ppm. The dry nitrogen gas was introduced at a rate of 5.0 mL/min, and the dry air was introduced at a rate of 50.3 mL/min. The residual toluene concentration in the catalytic gas was measured online every 3 min.The residual toluene concentration was analyzed using a gas chromatograph (GC9790-II, Zhejiang Fuli Analytical Instruments Co., China) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and a capillary column (HP-5, 30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 μm). The injector and detector temperatures were maintained at 200 °C and 250 °C, respectively. The oven temperature was initially set at 40 °C, held for 2 min, and then increased to 150 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas with a constant flow rate of 30 mL/min. A 1 µL gas sample was injected using a gas-tight microsyringe in split mode (split ratio 20:1). Under these conditions, toluene was well-resolved and quantified based on its retention time and peak area using external standard calibration.

Reaction activation energy analysis method for catalysts

There are many index parameters to evaluate the performance of catalysts, among which the reaction activation energy (Ea), as an index to judge the ease of carrying out catalytic reactions, is an important performance parameter of catalysts and can be calculated according to the Arrhenius Eq. (1). The accuracy of the obtained Ea values is enhanced by repeating the experiments for 3 times under identical conditions.

Transformation of Eq. (1)

where k is calculated using Eq. (3)

The meanings and units of the physical quantities in the formula are as follows: K is the reaction rate constant; A is the finger front factor; η is the toluene conversion rate; Ea is the reaction activation energy, J/mol; R is the fixed constant 8.314, J/(mol k); T is the Kelvin temperature, K; ν is the toluene carrier gas flow rate, mL/min; m is the mass of the catalyst, g; C0 is the initial concentration of toluene, ppm26.

Results and discussion

Texture and structures

The surface morphology and structure of Geo-3 catalyst was shown in Fig. 2. It can be observed from Fig. 2a,b that the geopolymer carrier is relatively regular spherical, with many pore structures of different sizes visible on the surface. In Fig. 2c,d, it is observed that there are many spherical particles of different sizes on the surface of the carrier. According to the literature27it is inferred that these particles are incomplete fly ash particles during the polymerization of the carrier. In addition, the difference of light and dark in different areas of the catalyst surface in Fig. 2a can be obviously observed. Combined with the CuMn mixture loaded on the surface of Geo-3 catalyst before calcination, it is speculated that the uneven light and dark in different areas is caused by the uneven distribution of CuMn particles on the surface of the geopolymer sphere during the preparation process and the different content of CuO on the surface of each area after calcination. Further magnification of the surface of the carrier showed many pores with diameters ranging from 0.5 to 2 microns, and many small catalyst particles of different sizes were also visible on the surface and in the pores. Figure 2e,f show the SEM characterization of Cu-Mn composite manganese catalyst. In the locally enlarged (e) and (f) figures, the irregular shape of crystals may be caused by the disorder of step growth during the crystallization process, resulting in crystal defects.

different measuring points in order to avoid accidental errors. The characterization results are shown in Table 2. There is a significant difference in Cu content between sampling point 1 and sampling points 2 and 3. These results confirmed the previous guesses on the distribution of the product microstructure.

Crystal phase composition and metallic state

Figure 3 shows the XRD pattern of Geo-3 catalyst. According to the comparison of JCPDS standard card data, it can be seen from the figure that quartz SiO2 is the main component of Geo-3 catalyst. Due to the low content of Cu, Mn and Fe on the geopolymer carrier, the corresponding oxides of the above three elements have weak peak intensity in the spectrum26. The spectral peaks at 30.3°, 43.5°, 47.4°, 50.1° and 57.5° correspond to (220), (400), (331), (422) and (511) crystal planes of CuMn2O4 cubic tip (JCPDS card number 34-1400), respectively. The peaks of 30.4°, 35.9°, 37.3°, 43.4°, 47.4° and 54.0° correspond to (220), (311), (222), (400), (311) and (422) crystal planes of Fe2O3 (JCPDS card No.75-0449), respectively. It is speculated that the corresponding oxides of Cu, Mn and Fe are CuMn2O4 and Fe2O3 respectively14. Combined with the EDS and XRD data of Geo-3 catalyst, it is confirmed that the purpose of loading Cu and Mn oxides onto the geopolymer composite spheres by in-situ synthesis method has been realized. In addition, it can be preliminarily determined that the active components of the Geo-3 catalyst are CuMn2O4 and Fe2O3.

In addition to the crystalline phases attributed to CuMn2O₄, Fe2O3, and quartz (SiO2), no distinct diffraction peaks corresponding to sodium aluminosilicate crystalline phases were observed in the XRD patterns of the Geo-3 catalyst. This absence of sharp peaks typically associated with sodium aluminosilicate phases, such as zeolites or sodalite, may be attributed to the predominantly amorphous nature of the geopolymer matrix. Previous studies have shown that geopolymers synthesized from fly ash often form a three-dimensional aluminosilicate gel network with low crystallinity, resulting in a broad hump in the 2θ range of 20°–35°, rather than sharp diffraction peaks. In the present study, a similar broad hump was observed in this region, suggesting the presence of an amorphous aluminosilicate gel structure, which is consistent with the typical characteristics of fly ash-based geopolymer materials.

In order to further validate the conclusion of XRD test on the catalytic active components in the catalyst, the Geo-3 catalyst was characterized by XPS. Figure 4a shows the full XPS spectrum of Geo-3 catalyst, and the main elements Si, O, Cu, Mn and Fe all have peaks in the catalyst.

Figure 4b shows the XPS spectrum of the Cu2p orbital of the Geo-3 in which there is an obvious output peak of the split spin-orbital, and the output peaks of 934.8 eV and 954.6 eV correspond to the Cu2p1 and Cu2p3 orbits respectively. Since the peak displacement and peak width of Cu2p1 and Cu2p3 in Cu2+ oxide are larger than those of Cu0 and Cu+ oxide, and there is no accompanying satellite peak when Cu0 and Cu+ oxide appear in XPS spectrum, it can be determined that Cu2p1 and Cu2p3 in Fig. 4b are Cu2+ oxide peaks. It is proved that the copper element in Geo-3 catalyst exists in the form of Cu2+.

Figure 4c is the orbital XPS spectrum of Mn2p in Geo-3. The orbital peak of Mn2p in manganese oxide shows an obvious split-orbital characteristic peak. Since only MnO has a satellite peak feature (647 eV) in the spectra of MnO, Mn2O3 and MnO2, and no satellite peak can be seen in the figure, it is concluded that Mn2+ does not exist in the Geo-3 catalyst. The Mn2p3 peak of Mn2O3 is around 641.4 eV, while the peak width and peak do not have an obvious recognizable shape as MnO2, indicating that the manganese in the Geo-3 mainly exists in the form of Mn2O3. Figure 4d is the XPS spectrum of the Fe2p orbital of the Geo-3, where the peak of Fe2p3 at 711.5 eV is closest to the standard peak of Fe2O3 (710.8 eV), and the peak of Fe2O3 shifts towards a higher binding energy, which proves that iron exists in the form of Fe3+ in the Geo-3 catalyst. It can be seen from the above analysis that the XPS characterization proves that Cu, Mn and Fe exist in the form of Cu2+, Mn3+ and Fe3+, respectively, and verifies the correctness of the assumption that CuMn2O4 and Fe2O3 are the active components in Geo-3 catalyst analyzed by XRD. The successful loading of Cu-Mn catalyst synthesized in situ was further verified.

The presence of CuMn2O₄ in the XRD pattern of Geo-3 can be explained by the thermal decomposition and solid-state reaction between copper and manganese precursors during the calcination process. At a calcination temperature of 500 °C, copper nitrate and manganese nitrate undergo decomposition to form CuO and Mn2O3, which then react to form CuMn2O₄ spinel-type oxides. This temperature is sufficient to initiate the crystallization of spinel CuMn2O₄, as has been reported in previous studies on Cu–Mn oxide catalysts calcined in the range of 450–550 °C. However, to further confirm the existence of the CuMn2O₄ phase and exclude the formation of isolated CuO or MnOx species, additional techniques such as Raman spectroscopy or high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) will be considered in future work.

Despite the relatively low Fe2O3 content (5.65 wt%) in the fly ash, its diffraction peaks were still detectable in the XRD pattern. This can be attributed to the high crystallinity and distinct diffraction characteristics of Fe2O3, particularly the α-Fe2O3 (hematite) phase, which exhibits strong and sharp peaks even at low concentrations. Additionally, Fe2O3 in fly ash is known to exist as well-formed crystalline domains that are readily detectable by XRD due to its high scattering factor and low background interference.

BET analysis

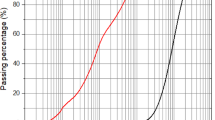

The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and pore size distribution of Geo based catalysts with different Cu/Mn ratios were measured using a fully automated surface area and porosity analyzer, as shown in Table 3. The average pore size of three catalysts is concentrated between 2 and 50 nm, belonging to mesoporous materials. When the Cu/Mn molar ratio of the sample is 5:3, the specific surface area reaches the maximum value of 74.08 m2/g, and its average pore size and total pore volume are 16.25 nm and 0.32 cm3/g, respectively. Within the relative pressure range of 0.5 ~ 1.0 (P/P0), the sample exhibits irreversible IV type N2 adsorption isotherms and H3 type hysteresis loops (Fig. 5), further confirming the existence of mesoporous structures. As the proportion of Mn in the catalyst increases, its specific surface area increases, possibly due to the higher Mn content promoting the formation of mesopores. In addition, according to Fig. 5; Table 3, the average pore size is the largest at 20.73 nm when the Cu/Mn ratio is 5:2. When the Cu/Mn ratio is 5:1, the average pore size is the smallest, at 13.76 nm. This indicates that different metal molar ratios significantly affect pore size, which may be related to the influence of different metal oxides on pore formation mechanisms during the synthesis process. Moreover, the micropore volume of the catalyst increases with the increase of Mn ratio, indicating that the increase of Mn content may be beneficial for the formation of microporous structure. Meanwhile, the mesopore volume remains relatively stable for all three catalysts, indicating that different Cu/Mn ratios have a relatively small impact on the formation of mesoporous structures.Interestingly, the BET analysis revealed that the specific surface area of the Geo-3 catalyst increased compared to the pristine geopolymer support. This enhancement can be attributed to the highly dispersed Cu and Mn oxide nanoparticles on the geopolymer surface, which prevent pore blockage and may introduce additional mesoporosity. Similar observations have been reported in previous studies, where the incorporation of metal nanoparticles led to an increase in surface area due to the creation of new porous structures and prevention of support agglomeration. Therefore, the observed increase in surface area in Geo-3 is consistent with these findings and suggests that the metal loading process was effective in enhancing the textural properties of the catalyst.“Although TPD characterization was not conducted in this study, future work should focus on quantifying the surface acidity and basicity of the catalysts to further elucidate their impact on catalytic efficiency.

Catalytic degradation performance

Due to the complexity of catalytic oxidation process, the reaction mechanism to explain the process is different. According to Mars and Van Krevelen, the process of gas-solid catalysis is mainly divided into the following two steps: (1) The reactants adsorb on the catalyst surface to form chemisorption species, and the species reacts with the lattice oxygen at the adsorption site. (2) The adjacent lattice oxygen is transferred to the reaction site, and the molecular oxygen is converted to the oxygen consumed by the lattice oxygen replenishment reaction on the catalyst. According to this mechanism, there are two kinds of adsorption sites and catalytic sites in the catalyst, and the number of sites is directly related to the catalytic performance of the catalyst.

The catalytic test results of Geo and Geo based catalysts were shown in Fig. 6. In the catalytic test experiment, the data taken in the figure are the average values of three parallel experiments at corresponding temperatures, and the influence of adsorption on toluene catalysis has been excluded. As can be seen from the figure, the catalytic effect of Geo-3 catalyst is the best, followed by Geo-2, Geo-1 and Geo. It is worth noting that Geo without Cu-Mn catalyst particles loaded still has 29.58% conversion efficiency, which may caused by the presence of Fe2O3 in Geo. Besides, it can be seen from the figure that the reaction temperature of Geo-3 catalyst is about 220 ℃, and the conversion rate of toluene can reach 97% when the temperature is about 300 ℃, which is lower than that of Geo-1 and Geo-2. The above results materials, which was more conducive to practical application.According to the Mars–van Krevelen (MvK) mechanism, the catalytic oxidation of toluene involves two main steps: (1) the adsorption and activation of toluene molecules on the catalyst surface, where they react with lattice oxygen to form intermediates and oxidized products; (2) the replenishment of consumed lattice oxygen by gaseous molecular oxygen, thereby regenerating the catalyst surface for the next cycle. This redox-based mechanism is widely accepted for transition metal oxide catalysts, particularly those involving Cu and Mn oxides, due to their ability to undergo reversible oxidation state changes, which facilitates efficient oxygen transfer during VOC oxidation.

The activation energies of Geo, Geo-1, Geo-2 and Geo-3 catalysts and T10, T50 and T90 are shown in Table 4. In origin, 1/T is taken as the horizontal coordinate and Ink as the vertical coordinate to draw a graph and carry out linear fitting, as shown in Fig. 7. Then the activation energy of the catalyst can be calculated according to the fitting slope. Geo-3 has the lowest activation energy of 123.0 kJ/mol when catalyzing the oxidation of toluene. Moreover, the obtained values of Ea were compared to literature values for similar catalysts, as shown in Table 4. From Table 4, the material prepared in this work has the uniqueness, especially Geo-3. In addition to the activation energy of the reaction, T10, T50 and T90 represent the temperature required for the catalytic reaction conversion rate to reach 10%, 50% and 90%, which is also an important parameter to measure the performance of the catalyst. It is further clear from the data in the table that when the conversion rate reaches 90%, the required temperature is Geo-1 > Geo-2 > Geo-3. In addition, the lower the activation energy in the catalytic process, the lower the required energy barrier and the easier the catalysis, etc., it can be concluded that Geo-3 has the best catalytic degradation ability of toluene, which is consistent with the results in Fig. 6. In addition, it can be seen from the obtained data that the fly ash geopolymer ball itself has the catalytic degradation ability of toluene, because the geopolymer contains certain Fe2O3, and it has a certain catalytic oxidation ability of toluene, which is consistent with previous literature reports28,29.

The Arrhenius plots and activation energy (Ea) values provided further insights into the differences in catalytic behavior among the four catalysts. As shown in Fig. 7; Table 4, the Ea values followed the order: Geo-3 (123.0 kJ/mol) < Geo-2 (147.2 kJ/mol) < Geo-1 (151.3 kJ/mol), indicating that Geo-3 required the lowest energy to initiate the toluene oxidation reaction. The lower Ea of Geo-3 can be attributed to its optimized Cu/Mn ratio (5:3), which enhances redox synergy between Cu2+ and Mn3+ active centers and promotes the formation of oxygen vacancies and mobile lattice oxygen species, thus facilitating the Mars–van Krevelen mechanism.

In contrast, Geo-1 with a Cu/Mn ratio of 5:1 showed the highest Ea, suggesting less efficient oxygen activation and weaker interaction between the metal oxides. This is consistent with the BET and XPS results, where Geo-1 exhibited lower specific surface area and potentially lower surface oxygen mobility. Geo-2 showed an intermediate Ea, indicating a partially enhanced redox property but still inferior to Geo-3.

The pristine geopolymer (Geo), although lacking Cu/Mn loading, still exhibited limited activity, likely due to the presence of Fe2O3 in the fly ash matrix, which provided minimal oxidation capacity. However, the absence of highly active Cu–Mn redox centers led to much higher reaction temperatures and non-observable kinetic linearity within the tested range.

These results collectively demonstrate that the variation in Cu/Mn ratio has a profound impact on the catalyst’s intrinsic kinetic parameters, affecting both the activation energy and the overall reaction temperature window for effective toluene oxidation.

Conclusion

The CuMn catalyst was successfully loaded onto the surface of spherical geopolymer by in-situ synthesis method. The results showed that the molar ratio of Cu/Mn content directly affected the surface characteristics and catalytic performance of Geo based catalyst. When the Cu/Mn ratio was 1:3, the specific surface area of the catalyst obtained was divided into CuMn2O4 and Fe2O3. Geo-3 catalyst showed highest catalytic oxidation capacity and lowest activation energy of 123.0 kJ/mol at the required temperatures of 222 ℃, 257 ℃ and 296 ℃ when the conversion rate of toluene was 10%, 50% and 90%, respectively. These findings not only provided a new way to prepare Geo based catalyst for toluene conversion, but also revealed the influence of different surface properties on the catalytic degradation ability.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

References

Guo, Y., Wen, M., Li, G. & An, T. Recent advances in VOC elimination by catalytic oxidation technology onto various nanoparticles catalysts: a critical review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 281, 119447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119447 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Microwave biochars produced with activated carbon catalyst: characterization and sorption of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Sci. Total Environ. 827, 153996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153996 (2022).

Wang, Y., Miao, Y., Li, S., Gao, L. & Xiao, G. Metal-organic frameworks derived bimetallic Cu-Co catalyst for efficient and selective hydrogenation of biomass-derived furfural to Furfuryl alcohol. Mol. Catal. 436, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcat.2017.04.018 (2017).

Boycheva, S. et al. Studies on non-modified and copper-modified coal Ash zeolites as heterogeneous catalysts for VOCs oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 361, 374–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.07.020 (2019).

Lou, B. et al. Catalytic oxidation of volatile organic compounds by non-noble metal catalyst: current advancement and future prospectives. J. Clean. Prod. 363, 132523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132523 (2022).

Hu, J., Li, W. B. & Liu, R. F. Highly efficient copper-doped manganese oxide Nanorod catalysts derived from CuMnO hierarchical nanowire for catalytic combustion of VOCs. Catal. Today. 314, 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2018.02.009 (2018).

Ye, Z. et al. Influence of the Preparation method on the activity of copper-manganese oxides for toluene total oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 223, 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.06.072 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Effect of the A-site cation over spinel AMn2O4 (A = Cu2+, Ni2+, Zn2+) for toluene combustion: enhancement of the synergy and the oxygen activation ability. Fuel 288, 119700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119700 (2021).

Kamal, M. S., Razzak, S. A. & Hossain, M. M. Catalytic oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) – A review. Atmos. Environ. 140, 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.05.031 (2016).

Kujawa, J., Cerneaux, S. & Kujawski, W. Removal of hazardous volatile organic compounds from water by vacuum pervaporation with hydrophobic ceramic membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 474, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2014.08.054 (2015).

Shah, R. K., Thonon, B. & Benforado, D. M. Opportunities for heat exchanger applications in environmental systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 20, 631–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-4311(99)00045-9 (2000).

Genuino, H. C., Dharmarathna, S., Njagi, E. C., Mei, M. C. & Suib, S. L. Gas-Phase total oxidation of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes using Shape-Selective manganese oxide and copper manganese oxide catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 12066–12078. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp301342f (2012).

Liu, B. et al. Catalytic ozonation of VOCs at low temperature: A comprehensive review. J. Hazard. Mater. 422, 126847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126847 (2022).

Behar, S., Gonzalez, P., Agulhon, P., Quignard, F. & Świerczyński, D. New synthesis of nanosized Cu–Mn spinels as efficient oxidation catalysts. Catal. Today. 189, 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2012.04.004 (2012).

Su, D. S., Perathoner, S. & Centi, G. Nanocarbons for the development of advanced catalysts. Chem. Rev. 113, 5782–5816. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr300367d (2013).

Wang, J. et al. On the CuO-Mn2O3 oxide-pair in CuMnOx multi-oxide complexes: structural and catalytic studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 575, 151733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.151733 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. A facile synthesis for porous CuO/Cu2O composites derived from MOFs and their superior catalytic performance for CO oxidation. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 86, 74–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2017.09.027 (2017).

Novais, R. M., Seabra, M. P. & Labrincha, J. A. Porous geopolymer spheres as novel pH buffering materials. J. Clean. Prod. 143, 1114–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.008 (2017).

Lu, M. et al. Potentiality of the porous geopolymer sphere in adsorption of Pb (II) from aqueous solutions: behaviors and mechanisms. Ceram. Int. 49, 698–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.09.040 (2023).

Tan, T. H., Mo, K. H., Lai, S. H. & Ling, T. C. Synthesis of porous geopolymer sphere for Ni(II) removal. Ceram. Int. 47, 29055–29063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.06.268 (2021).

Li, J. R., Wang, F. K., He, C., Huang, C. & Xiao, H. Catalytic total oxidation of toluene over carbon-supported CuCo oxide catalysts derived from Cu-based metal organic framework. Powder Technol. 363, 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2019.12.060 (2020).

Novais, R. M. et al. Synthesis of porous biomass fly ash-based geopolymer spheres for efficient removal of methylene blue from wastewaters. J. Clean. Prod. 207, 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.265 (2019).

Xu, H. & Van Deventer, J. S. J. The geopolymerisation of alumino-silicate minerals. Int. J. Min. Process. 59, 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-7516(99)00074-5 (2000).

Odularu, A. T. & Metal Nanoparticles Thermal Decomposition, Biomedicinal Applications to Cancer Treatment, and Future Perspectives. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 9354708, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9354708 (2018).

Cotin, G. et al. Unravelling the thermal decomposition parameters for the synthesis of anisotropic Iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 8 https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8110881 (2018).

Aguilera, D. A., Perez, A., Molina, R. & Moreno, S. Cu–Mn and Co–Mn catalysts synthesized from hydrotalcites and their use in the oxidation of VOCs. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 104, 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.02.019 (2011).

Chen, X. et al. Catalytic combustion of toluene over mesoporous Cr2O3-supported platinum catalysts prepared by in situ pyrolysis of MOFs. Chem. Eng. J. 334, 768–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.10.091 (2018).

Niu, H., Liu, S., Cai, Y., Wu, F. & Zhao, X. MOF derived porous carbon supported Cu/Cu2O composite as high performance non-noble catalyst. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 219, 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.07.027 (2016).

Peng, B., Feng, C., Liu, S. & Zhang, R. Synthesis of CuO catalyst derived from HKUST-1 temple for the low-temperature NH3-SCR process. Catal. Today. 314, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2017.10.044 (2018).

Sihaib, Z. et al. Manganese oxide-based catalysts for toluene oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 209, 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.03.042 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by the Provincial Natural Science Foundations of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2022D01C28); Research and development of major common key technologies of zero loss of slag slurry are gratefully acknowledged (2022A01006-3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“D.C. and J.F. primarily conceptualized the research project and drafted the manuscript, sharing equal contribution. Q.G. and M.Z. contributed to the experimental design and data analysis, with M.Z. also serving as the corresponding author. H.Y. was involved in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. X.L. coordinated the research collaboration and was responsible for funding acquisition. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.”

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Author Xiaoyang Liang was employed by Xinjiang Greens Energy Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors (Dejun Chen, Jiawei Feng, Qingqing Guan, Mengqi Zhao, Hao Yuan) declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Feng, J., Guan, Q. et al. Catalytic activity of supported Cu-Mn/fly ash geopolymer for the oxidative removal of toluene. Sci Rep 15, 42567 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07359-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07359-x