Abstract

Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi form symbiotic relationships with plants, using their hyphae to enhance nutrient uptake and promote plant growth. Alternanthera philoxeroides, an invasive species, poses a significant threat to agriculture, forestry, and urban ecosystems in China. However, there is a lack of research on how AM fungi influence invasive plants under varying environmental conditions. This study explored the effects of two AM fungal strains and four substrate types on A. philoxeroides. The results showed that the mycorrhizal dependency of A. philoxeroides ranged from 6.09% and 37.21%. Plant height and root length of A. philoxeroides were primarily shaped by substrate quality. AM fungi significantly enhanced root and aboveground biomass, especially under nutrient-poor conditions. Leaf area increased in response to fungal inoculation, while leaf number was regulated by substrate nutrients. Overall, AM fungi promoted biomass accumulation, particularly when combined with nutrient-enriched substrates, underscoring their potential application in invasive plant management. Therefore, future management strategies should divide invaded areas into distinct control zones based on gradients of soil nutrient levels, with special attention given to key regions for targeted monitoring and prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological invasions not only cause significant losses in agriculture, forestry, and animal husbandry, but also lead to long-term ecological impacts. In China, the direct and indirect economic losses attributed to invasive alien species amount to approximately 119.876 billion yuan annually, accounting for 1.36% of the national gross domestic product1. The invasion of alien species disrupts ecosystem structure and function. A. philoxeroides, native to South America, has now spread to North America, Oceania, Southeast Asia, and China2. In China, it is predominantly distributed in low-altitude areas south of 44°N and east of 97°E, characterized by warm and humid climates. In 2003, A. philoxeroides was listed among the “First Batch of Invasive Alien Species in China” by the State Environmental Protection Administration. The success of plant invasions into new environments is often closely linked to the relationship between invasive plants and local AM fungi3.

Mycorrhizae are common and ecologically important symbiotic associations, with AM fungi forming mutualistic relationships with approximately 80% of terrestrial plant4. Through extra-root, AM fungi connect the roots of different plants, creating an extensive hyphal network. These networks facilitate the uptake and transfer of nutrients, water, and other resources from the surrounding environment to the host plants5,6, thereby enhancing drought tolerance and improving resistance to various plant pathogens7,8,9. Previous studies have demonstrated diverse effects of invasive plants on AM fungal communities. For example, the invasion of Solidago canadensis promoted the growth of Glomus mosseae but inhibited Glomus geosporum10. Similarly, exotic plants such as Bromus tectorum and Euphorbia esula have been reported to enhance AM fungal development11. In contrast, Eupatorium adenophorum invasion reduced the abundance of AM fungi like Glomus geosporum, while stimulating the growth of Glomus claroideum12.

Some evidence suggests that AM fungi do not enhance the growth of invasive plant, indicating a lack of effective symbiotic association between the fungi and alien plants13. In certain cases, a negative relationship between AM fungi and invasive plants has been observed14,15. For instance, the biomass of two weed species decreased significantly—by 59% and 66%, respectively—when inoculated with AM fungi, while four other weed species exhibited biomass reductions ranging from 20 to 37% under similar conditions14. Furthermore, AM fungi have been shown to exert antagonistic effects on species such as Luzula campestris, leading to reduced plant biomass16. Some researchers even argue that no significant interactions exist between AM fungi and exotic species17, with similar conclusions reported specifically for Luzula campestris18. A meta-analysis further supports the notion that AM fungal colonization is not consistently altered invasive plants19. Collectively, these findings suggest that the interactions between invasive plants and AM fungi can result in either positive20 or negative feedback10.

Mycorrhizal fungi are widely recognized for their role in enhancing nutrient acquisition in host plants. Soil nutrient availability is also considered a critical factor influencing the success of plant invasions21,22. Several studies have found that highly invasive alien species often respond more positively to increased nutrient availability compared to native species23. Conversely, elevated nutrient levels may interfere with the establishment of beneficial mycorrhizal associations, thereby diminishing the advantage conferred by AM fungi24. Research into how invasive plants respond to environmental nutrient gradients indicates that greater resource availability can facilitate their adaptation to local conditions23,25.

Despite growing interest in the ecological dynamics between invasive plants and AM fungi8,20,23,25, relatively little is known about the specific interactions between AM fungi and A. philoxeroides. Moreover, biomass allocation between aboveground and belowground organs reflects plant growth strategies and resource-use patterns under different substrate conditions. Plants typically prioritize the development of organs involved in acquiring the most limiting resource—either light (aboveground biomass) or soil nutrients and water (root biomass). This trade-off is central to plant adaptive responses and ecological success across variable environments26. Based on this background, the present study tests the following hypotheses: (1) A. philoxeroides exhibits a positive feedback relationship with AM fungi. (2) The mycorrhizal dependency of A. philoxeroides varies between two different AM fungal strains. (3) The biomass of A. philoxeroides increases with the increase of nutrients in the growing substrate.

Materials and methods

Materials

In this study, A. philoxeroides were collected from an abandoned farmland heavily invaded by the species in Zunyi, China (Longitude: 107.05°E, Latitude: 27.71°N). Stem segments with uniform growth status were selected from the middle portion of the plant. Each segment was approximately 6 cm in length and contained one node. Prior to transplantation, stem segments were surface-sterilized by immersing them in 70% ethanol for 5 s, then promptly removed and inserted into designated growth substrates. Moisture was maintained using water-retentive tissue, and deionized water was added regularly to ensure adequate hydration. The experiment was conducted under natural outdoor conditions, with daytime temperatures ranging from 23 °C to 27 °C.

Two AM fungal strains were employed in the experiment. AM fungus a was Rhizophagus intraradices (BGCBJ09), originally isolated from tomato roots, and AM fungus b was Funneliformis mosseae (BGCXZ02A), isolated from Incarvillea younghusbandii. Both fungal strains were provided by the Institute of Plant Nutrition and Resources, Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry (http://www.baafs.net.cn/index.aspx).

Four types of growth substrates were prepared, each comprising a 1:1:1:1 ratio of river sand, vermiculite, perlite, and one organic amendment: (1) Soil treatment: supplemented with loess; organic matter content 0.74%, total nitrogen 0.039%. (2) Cow manure treatment: supplemented with cow manure; organic matter 6.41%, total nitrogen 0.24%. (3) Vermicompost treatment: supplemented with vermicompost; organic matter 4.87%, total nitrogen 1.13%. (4) Mixed treatment: supplemented with cow manure and vermicompost; organic matter 11.27%, total nitrogen 0.52%.

Experimental design

A pot experiment was conducted using sterilized substrates. Each plastic pot (dimensions: 20.5 cm × 14.5 cm × 18.5 cm) was filled with 2 kg of substrate. The experimental design included two AM fungal strains and four substrate types. Each treatment was replicated three times, with three A. philoxeroides individuals planted per pot, resulting in a total of 36 pots.

The control group received no AM fungal inoculation. For the AM-inoculated groups, 15 g of inoculum containing spores of AM fungus a (3.2 spores/g) or AM fungus b (3.0 spores/g) was thoroughly mixed with each respective substrate. Substrate moisture was maintained at approximately 80%, and plants were cultivated outdoors under natural conditions (23–27 °C).

Data collection and analysis

Morphological and physiological measurements

Plant height was measured using a tape measure. After 45 days of growth, the number of leaves and total leaf area were recorded prior to harvest. Following harvest, aboveground and belowground biomass, root length, and chlorophyll content were determined.

Fresh A. philoxeroides roots were collected, cleaned with potassium hydroxide, and then stained with Trypan Blue according to the previous reported method27. The grid line intersection method was used for mycorrhizal root colonization28.

Calculation the infection rate of 100 root segments for each sample, and take the average as the AM fungi infection index for that sample.

Number of Colonized Root Segments: the number of root segments (out of the total segments) that show visible signs of AM fungi colonization (e.g., presence of hyphae, arbuscules, or vesicles).

Total Number of Root Segments Examined: the total 100 number of root segments into which the roots were divided.

Chlorophyll content determination

Fresh leaf samples from each treatment group were collected, coarse veins removed, and the tissue cut into small pieces. Approximately 0.5 g of leaf tissue was ground with quartz sand and calcium carbonate in a mortar. Pigments were extracted with an appropriate solvent, and absorbance was measured at 663 nm, 645 nm, and 470 nm using a UV spectrophotometer. Chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were calculated using the following formulas29,30:

Chl a:Chlorophyll a concentration; Chl b:Chlorophyll b concentration; Car: Carotenoid concentration.

The dependency on mycorrhizae is calculated according to the following formula.

MD: Mycorrhizal dependency; Binoc: above-biomass of A. philoxeroides inoculated AM fungi; Bnon: above-biomass biomass of A. philoxeroides non-inoculated AM fungi.

Statistical analysis

Preliminary data processing using Excel, perform statistical analysis on experimental data using SPSS 18 software General Linear Model (GLM), and perform multiple comparison tests on different processed data (p < 0.05).

Results

Infection rate of AM fungi

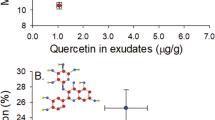

Compared with the control group, the infection rates of AM fungi a on A. philoxeroides were higher than that of AM fungi b (Fig. 1). Infections were at the marginal significant (F = 3.87, p = 0.05) between A. philoxeroides and AM fungi (a and b). Similarly, four types of growth substrates (soil treatment, cow manure, vermicompost, and mix manure) had obviously affected infection rate of AM fungi on A. philoxeroides (F = 15.44, p < 0.01). Four types of growth substrates didn’t change mycorrhizal dependency (F = 1.71, p = 0.17) in A. philoxeroides. And two types AM fungi (a and b) didn’t shift mycorrhizal dependency (F = 1.40, p = 0.24).

AM fungi and substrates on chlorophyll

No significant interaction effects between AM fungi and different growth substrates were observed for chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, or carotenoids in A. philoxeroides (Fig. 2). Chl a levels ranged from 0.77 to 1.01 mg/g, while Chl b levels ranged narrowly between 0.28 and 0.41 mg/g (Table S2). Across all four substrates, the contents of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b were higher in plants inoculated with AM fungus strain b than in those inoculated with strain a (Fig. 2). In particular, chlorophyll b content in plants grown in cow manure and vermicompost substrates was significantly higher when inoculated with AM fungus strain b than with strain a (Fig. 2).

AM fungi on growth of A. philoxeroides

As shown in Fig. 3, treatment with AM fungus strain a promoted an increase in plant height of A. philoxeroides in cow manure treatment, however, the difference in height between fungal treatments was not statistically significant (F = 0.91, p = 0.41). In contrast, the type of growth substrate had a significant effect on plant height (F = 6.81, p < 0.01).

Substrate type also significantly influenced root length (Fig. 4, F = 3.06, p < 0.05), whereas AM fungal strain did not. In the soil treatment group, inoculation with AM fungi strains a and b significantly increased the root length of A. philoxeroides (Fig. 4). As shown in Figure 4, the effect of AM fungi on the root length of A. philoxeroides appears to be modulated by the type of growth substrate.

AM fungal strain significantly affected root biomass (F = 5.88, p < 0.01, Fig. 4), whereas substrate type did not exert a significant effect (F = 0.59, p > 0.05, Fig. 4). In the absence of AM fungal inoculation, the root biomass of A. philoxeroides increased with improved substrate nutrient levels. Although AM fungal inoculation enhanced root biomass across all treatments, the effect was most pronounced under nutrient-poor soil conditions (Fig. 4). Importantly, the interaction between fungal strain and substrate treatment was not statistically significant (p > 0.05, Fig. 4), suggesting independent effects on root biomass.

AM fungi effect on growth of A. philoxeroides

The number of leaves per plant was significantly influenced by the type of growth substrate (F = 3.06, p < 0.05, Fig. 5) but not by AM fungal strain (F = 0.50, p > 0.05, Fig. 5), indicating that nutrient availability plays a crucial role in leaf development. Conversely, AM fungal strain had a significant effect on leaf area (F = 4.07, p < 0.05, Fig. 5), whereas substrate type did not (F = 0.82, p > 0.05, Fig. 5), suggesting differential responses of leaf number and area to the two factors.

Aboveground biomass was significantly affected by AM fungal strain (F = 4.68, p < 0.01, Fig. 6), while substrate treatment had no significant impact (F = 1.76, p > 0.05, Fig. 6). In the absence of AM fungal inoculation, the aboveground biomass of A. philoxeroides increased with increasing substrate nutrient levels. Similar trends were observed in AM fungi-inoculated groups, where biomass accumulation showed a positive correlation with nutrient enrichment.

Total biomass per plant was also significantly influenced by AM fungal strain (F = 5.17, p < 0.01, Fig. 6), but not by substrate treatment (F = 1.37, p > 0.05, Fig. 6). No significant interaction was observed between AM fungal strain and growth substrate for either aboveground or total biomass. In general, nutrient-rich substrates promoted biomass accumulation, particularly in AM fungi-inoculated groups.

Discussion

AM fungi colonization and mycorrhizal dependency

Mycorrhizal dependency is a key indicator for assessing the contribution of AM fungi to plant growth. It is influenced by the nutrient availability of the growth environment and the resource utilization strategies adopted by plants. In this study, the mycorrhizal dependency of A philoxeroides varied between 6.09% and 37.21% under inoculation with AM fungi strain a and b. Notably, AM fungi b—originating from a natural environment—showed stronger symbiotic performance with A. philoxeroides than AM fungi a, which was sourced from an agricultural field. The degree of symbiosis is determined by both the host plant and the AM fungal strain. A significant difference in colonization rates was observed between the two AM fungi (Fig. 1), supporting previous findings that various exotic invasive species can be colonized by AM fungi13,31. These outcomes are influenced by mycorrhizal strain, plant species, and environmental conditions32,33.

Compared to an average mycorrhizal dependency of 56% observed across 260 plant species in earlier studies34, the values in our study were lower. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that prior studies mainly examined native plants that had developed long-term symbiotic relationships through co-evolution. In contrast, A. philoxeroides is an alien herbaceous species, and its relatively low mycorrhizal dependency aligns with previous findings suggesting lower symbiosis under adverse conditions35.

Interestingly, our data revealed that the highest mycorrhizal dependency occurred in nutrient-poor soil treatments, while the lowest was found in nutrient-rich (cow manure) conditions. This finding is consistent with the notion that AM fungi play a greater role in nutrient acquisition in resource-poor environments36.

The establishment of mycorrhizal symbiosis is influenced by both the physiological status of the plant and the characteristics of AM fungi within a given soil environment37. Mycorrhizal colonization also affects nutrient uptake and root signaling38. As different AM fungi form specific functional groups with their plant partners, they differentially influence host growth.

Our 45-day growth experiment involving A. philoxeroides and two AM fungal stains (a and b) likely represents a relatively short period for robust symbiotic establishment. Nonetheless, the observed colonization rates, biomass enhancement, and mycorrhizal dependency support Hypotheses 1 and 2.

AM fungi promote growth by optimizing resource allocation

AM fungi assist host plants in nutrient acquisition and can partially replace root function, thus affecting plant biomass allocation patterns19,39,40,41. While roots play a central role in water and nutrient absorption, their construction consumes considerable carbon and energy. The presence of AM fungi can mitigate this trade-off by enhancing nutrient uptake efficiency, thereby allowing plants to invest more resources in above-ground structures like leaves.

Our findings demonstrated that both AM fungi treatments significantly increased the leaf area of A. philoxeroides, supporting the “functional substitution” hypothesis whereby AM fungi enable plants to reduce root investment and reallocate carbon to photosynthetic organs.

Moreover, AM fungal inoculation contributed to increase above-ground biomass (Fig. 6), underscoring the mutualistic relationship between AM fungi and invasive plants42. These results strongly support the "optimal resource allocation hypothesis," which suggests that plants allocate biomass to organs that facilitate access to the most limiting resources43,44.

In the absence of AM fungal inoculation, the above ground biomass of A. philoxeroides increased with increasing substrate nutrient (Fig. 6), and higher nitrogen content in the substrate correlated with larger leaf area (Fig. 5), suggesting that nutrient-rich environments promote invasion even without AM fungal symbiosis. This aligns with studies indicating that nitrogen enrichment enhances the competitive ability of invasive species such as Flaveria bidentis32. In the group without inoculation with AM fungi, biomass increased with increasing substrate nutrition, supporting hypothesis 3.

Given that both stems and roots are vital reproductive structures in A. philoxeroides, the promotion of total biomass by AM fungi across all substrate types—especially nutrient-poor substrate—implies that AM fungi may enhance the invasive potential of this species in low-nutrient environments.

Interactions between AM fungi and substrate nutrients influence plant growth

The symbiotic benefits conferred by AM fungi are influenced by both nutrient availability and fungal strain. Substrate nutrient levels that are either excessive or deficient can inhibit AM fungal spore germination, hyphal growth, and root colonization. For instance, high organic matter content has been shown to reduce AM fungal abundance45. Our findings on colonization rates and mycorrhizal dependency across different substrates support this pattern (Fig. 1). AM fungi are also known to modulate plant hormone levels in response to substrate conditions46. Overall, our results highlight an interaction between AM fungi and substrate nutrient status47,48, which ultimately affects plant biomass accumulation and the allocation of resources among different plant organs.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that both AM fungal strains and substrate types independently affect the colonization rate and physiological performance of A. philoxeroides. AM fungal strain a showed higher infection rates compared to strain b, while different growth substrates significantly influenced infection levels but did not affect mycorrhizal dependency. Plant height and root length were primarily shaped by substrate quality. Root biomass and aboveground biomass were significantly increased by AM fungi, especially under nutrient-poor conditions. Furthermore, leaf area responded positively to fungal inoculation. Overall, AM fungi improved biomass accumulation in A. philoxeroides, particularly when combined with nutrient-enriched substrates.

Implications

This study confirmed that the mycorrhizal dependency of A. philoxeroides is lower than values reported in previous literature. Some research suggests that plant functional group and soil environment are critical factors influencing AM fungi-mediated growth promotion18, while others argue that certain recently evolved AM fungal taxa more effectively enhance host biomass than ancient taxa6. These findings highlight the need for deeper investigation into plant-AM fungi interactions across diverse fungal strains.

Furthermore, the plasticity of invasive plant organs—reflected in changes in leaf number, leaf area, root length, and biomass under different substrates and AM fungi—contributes to their adaptability. This is consistent with findings from Erigeron canadensis, which alters reproductive strategies across habitats by adjusting organ size and number26.

Future research should investigate how above- and below-ground organ plasticity and reproductive strategies together shape invasion mechanisms in alien plants. A comprehensive understanding of these dynamics will be essential for managing biological invasions.

Data availability

Data is provided within the supplementary information files.

References

Wang, R. & Feng, Y. The effects of leaf phenology, construction cost and payback time on carbon accumulation in invasive plants. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2009(5), 2568–2577 (2009).

Julien, M. H., Skarratt, B. & Maywald, G. F. Potential geographical distribution of alligator weed and its biological control by Agasicles hygrophila. J. Aquat. Plant Manag. 33(4), 55–60 (1995).

Zhang, B., Wang, P. & Jin, X. Ornamental plants and biological invasion. North. Hortic. 5, 178–183 (2018).

Brundrett, M. & Tedersoo, L. Evolutionary history of mycorrhizal symbioses and global host plant diversity. New Phytol. 220(4), 1108–1115 (2018).

Bender, S., Wagg, C. & Van der Heijden, M. An underground revolution: biodiversity and soil ecological engineering for agricultural sustainability. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31(6), 440–452 (2016).

Säle, V. et al. Ancient lineages of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi provide little plant benefit. Mycorrhiza 31(5), 559–576 (2021).

Jia, Y., Van der Heijden, M., Wagg, C., Feng, G. & Walder, F. Symbiotic soil fungi enhance resistance and resilience of an experimental grassland to drought and nitrogen deposition. J. Ecol. 109, 1365–1390 (2020).

Zhou, L. et al. Global systematic review with meta-analysis shows that warming effects on terrestrial plant biomass allocation are influenced by precipitation and mycorrhizal association. Nat. Commun. 13, 4914 (2022).

Van der Heijden, M., Martin, F., Selosse, M. & Sanders, I. Mycorrhizal ecology and evolution: The past, the present and the future. New Phytol. 205, 1406–1423 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. Positive feedback between mycorrhizal fungi and plants influences plant invasion success and resistance to invasion. PLoS ONE 5(8), e12380 (2010).

Lekberg, Y., Gibbons, S., Rosendahl, S. & Ramsey, P. Severe plant invasions can increase mycorrhizal fungal abundance and diversity. ISME J. 7(7), 1424–1433 (2013).

Yu, W., Liu, W. & Gui, F. Invasion of exotic Ageratina adenophora Sprengel. alters soil physical and chemical characteristics and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus community. Acta Ecol. Sin. 32(22), 7027–7035 (2012).

Checinska Sielaff, A., Polley, H., Fuentes-Ramirez, A., Hofmockel, K. & Wilsey, B. Mycorrhizal colonization and its relationship with plant performance differs between exotic and native grassland plant species. Biol. Invasions 21(6), 1981–1989 (2019).

Rinaudo, V., Bàrberi, P., Giovannetti, M. & Van der Heijden, M. Mycorrhizal fungi suppress aggressive agricultural weeds. Plant Soil 333, 7–20 (2010).

Urcelay, C., Vaieretti, M., Pérez, M. & Diaz, S. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal colonisation on shoot and root decomposition of different plant species and species mixtures. Soil Biol. Biochem. 43, 466–468 (2011).

Veiga, R. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi reduce growth and infect roots of the non-host plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 223, 867–881 (2013).

Shah, M., Reshi, Z. & Khasa, D. Arbuscular mycorrhizas: Drivers or passengers of alien plant invasion. Bot. Rev. 75, 397–417 (2009).

Romero, F., Argüello, A., de Bruin, S. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. The plant–mycorrhizal fungi collaboration gradient depends on plant functional group. Funct. Ecol. 37(9), 2386–2398 (2023).

Bunn, R., Ramsey, P. & Lekberg, Y. Do native and invasive plants differ in their interactions with, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi? A meta-analysis. J. Ecol. 103, 1547–1556 (2015).

Han, X., Su, J., Yao, N. & Chen, B. Advances in root foraging behavior of exotic invasive plants. Biodivers. Sci. 28(6), 727–733 (2020).

Bradley, B., Blumenthal, D., Wilcove, D. & Ziska, L. Predicting plant invasions in an era of global change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 310–318 (2010).

Enders, M. et al. A conceptual map of invasion biology: Integrating hypotheses into a consensus network. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29(6), 978–991 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Do invasive alien plants benefit more from global environmental change than native plants?. Glob. Change Biol. 23(8), 3363–3370 (2017).

Hoeksema, J. et al. A meta-analysis of context-dependency in plant response to inoculation with mycorrhizal fungi. Ecol. Lett. 13(3), 394–407 (2010).

Dawson, W., Fischer, M. & van Kleunen, M. Common and rare plant species respond differently to fertilisation and competition, whether they are alien or native. Ecol. Lett. 15, 873–880 (2012).

Zhang, B., Sun, Q., Huang, X. & Zeng, G. Resource allocation characteristics of invasive small flying pods of different sizes. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 50(5), 107–113 (2022).

Phillips, J. M. & Hayman, D. S. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 55(1), 158–161 (1970).

Giovannetti, M. & Mosse, B. An evaluation of techniques for measuring vesicular arbuscular infection in roots. New Phytol. 84(3), 489–500 (1980).

Wang, X. & Huang, J. Principles and Techniques of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Experiments. Beijing. Higher Education Press (2015).

Zhang, B., Peng, Y., Zang, L. & Qin, K. Plasticity of Alernantlhera philoxeroites in response to three kast habitats. Guithaia 37(6), 702–706 (2017).

Kleunen, M., Weber, E. & Fischer, M. A meta-analysis of trait differences between invasive and non-invasive plant species. Ecol. Lett. 13(2), 235–245 (2010).

Zhang, F. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi facilitate growth and competitive ability of an exotic species Flaveria bidentis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 115(115), 275–284 (2017).

Yuan, Y. et al. an invasive plant promotes its arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses and competitiveness through its secondary metabolites: Indirect evidence from activated carbon. PLoS ONE 9(5), e9716 (2014).

Tawaraya, K. Arbuscular mycorrhizal dependency of different plant species and cultivars. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 49(5), 655–668 (2003).

Brundrett, M. Coevolution of roots and mycorrhizas of land plants. New Phytol. 154(2), 275–304 (2002).

Camuy-Velez, L. et al. Context-dependent contributions of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to host performance under global change factors. Soil Biol. Biochem. 204, 109707 (2025).

Willing, C., Wan, J., Yeam, J., Cessna, A. & Peay, K. G. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi equalize differences in plant fitness and facilitate plant species coexistence through niche differentiation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8(12), 2337–2337 (2024).

Tedersoo, L., Bahram, M. & Zobel, M. How mycorrhizal associations drive plant population and community biology. Science 367(6480), eaba1223 (2020).

Moora, M. et al. Alien plants associate with widespread generalist arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal taxa: Evidence from a continental-scale study using massively parallel 454 sequencing. J. Biogeogr. 38(7), 1305–1317 (2011).

Nuñez, M. & Dickie, I. Invasive belowground mutualists of woody plants. Biol. Invasions 16(3), 645–661 (2014).

Smith, S. & Read, D. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis 3rd edn. (Academic, 2008).

Johnson, N. Resource stoichiometry elucidates the structure and function of arbuscular mycorrhizas across scales. New Phytol. 185, 631–647 (2009).

Bloom, A., Chapin Iii, F. S. & Mooney, H. A. Resource limitation in plants—An economic analogy. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 16, 363–392 (1985).

Ren, Z., Sun, Y. & Huang, W. Responses of invasive alien plant Erigeron canadensis L. to nutrient availability and fluctuations. Plant Sci. 41(5), 626–635 (2023).

Chen, N. et al. Effects of culture substrates on development of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 23(9), 205–207 (2007).

Shi, J., Wang, X. & Wang, E. Mycorrhizal symbiosis in plant growth and stress adaptation: from genes to ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 74, 569–607 (2023).

Camuy-Velez, L. et al. Context-dependent contributions of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to host performance under global change factors. Soil Biol. Biochem. 204, 109707 (2025).

Wang, M. et al. Context-dependent plant responses to arbuscular mycorrhiza mainly reflect biotic experimental settings. New Phytol. 240(1), 13–16 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Zhijie Zhang for his help in language modification. Similarly, we would like to thank Minggui Gong for providing valuable revision suggestions, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the high-level talent project of Moutai Institute (mygccrc[2022]051 and mygccrc[2022]070).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Baocheng Zhang and Gang Zeng conceived and designed the experiments. Lingling Shen performed the experiments. Ziping Pan and Changbin Pan analyzed the data . All authors have reviewed and agreed with the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., Shen, L., Pan, Z. et al. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and soil substrate on invasive plant Alternanthera philoxeroides. Sci Rep 15, 21461 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07390-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07390-y