Abstract

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is the most diagnosed cancer among young adults between the ages of 15 to 19 years. This study aims to update the HL incidence trends by age, sex, and race/ethnicity among children and adolescents in the United States (US) from 2000 to 2020. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 22 data were utilized to estimate counts, age-adjusted incidence rates, and trends. HL patients were identified using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology version 3. The annual percent change (APC) and average APC (AAPC) were computed using joinpoint regression. Between 2000 and 2019, the US documented a cumulative total of 10,007 of pediatric HL spanning various age categories. Classical HL comprised the majority (92.98%) of cases, predominantly affecting non-Hispanic Whites (53.28%) and individuals aged 15–19 years (66.35%). Trends in AAPCs showed no notable alterations. However, both incident cases and rates demonstrated a consistent rise with increasing age. While no significant changes were observed in the overall incidence trend of pediatric HL from 2000 to 2019, discrepancies persist among the results of different studies. Additional research is warranted to explore potential underlying factors that may influence these observed trends.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a lymphoid neoplasm that is responsible for around 3 and 11% of all childhood (from birth to age 14 years) and adolescent (age 15 to 19 years) cancers in the United States (US), respectively1. It has been convincingly identified that Epstein-Barr virus infection2, immunosuppression and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection/ acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)3, autoimmune disorders4, certain genetic features5, and environmental factors such as obesity6 and high birthweight7 are associated with increased risks for HL. The incidence of HL among children and adolescents varies depending on age, with being the most typically diagnosed cancer among individuals aged 15 to 19 years and being rare in infants8. In 2019, the age-standardized incidence, prevalence, death, and disability-adjusted life-year rates for childhood HL globally were 0.24, 1.35, 0.09, and 7.11 cases per 100,000 individuals, respectively9.In economically prosperous countries like the US, HL has two distinct periods of occurrence. These periods are characterized by a high number of cases, with one surge occurring in young adults and another in individuals over 50 years. It is worth noting that the majority of patients are young adults8,10. In economically challenged locations, this bimodal age distribution has been observed in males: Boys experience a first surge during youth, followed by lower rates inyoung adults, and finally, a second surge in older adults11. The incidence of HL among children and adolescents in the US is higher in males compared to females, with a male-to-female incidence rate ratio of 1.1012. Among different race/ethnicity groups, White individuals were diagnosed with HL at a higher rate than Blacks and Hispanics. However, the incidence rates were higher in Hispanic children between the ages of 0 to 4 years and 5 to 9 years13.

Studies on different epidemiological aspects of HL exist in other countries14,15,16. Despite these insights, prior US studies have not focused exclusively on pediatric HL incidence trends by histologic subtype, age, sex, and race/ethnicity over a 20-year span nor assessed the early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent analysis of pediatric cancer trends (2003–2019) included HL among many cancers but lacked HL-specific, subtype-level detail and did not cover 202012. We therefore aimed to investigate recent HL incidence trends by age, sex, and race/ethnicity among children and adolescents in the US from 2000 to 2020, thereby encompassing the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the potential for diagnostic delays, this study cannot assess cases that may have been deferred into 2021.

Methods

Sources of data

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) version 22 covers about 48% of the population in the US and offers information regarding the survival rates of patients and the stage of cancer at the time of diagnosis17. The SEER program gathers data regarding the patient’s demographic characteristics, initial tumor location, morphology, stage of diagnosis, initial treatment administered, and subsequent monitoring of vital status17. This investigation utilized the SEER 22 database, which was accessible in April 2023 and included data reported in November 2022. The objective was to estimate the incidence rates and annual percent changes (APCs) of pediatric HL from 2000 to 202018,19. The SEER 22 database was utilized in accordance with the SEER Research Data Agreement for 1975–2020 Data20, and statistics were subsequently published accordingly21.

Definitions

The presentation of cases of cancer involves the use of frequencies and percentages, whereas the incidence rate is expressed as the numbers per 100,000 individuals. The APCs of HL within a specific period show fluctuations at a consistent ratio of the rate reported in the previous year. The average APCs (AAPCs) denote the average value of several APCs during a specific time frame. The patients were in three groups for race/ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White (NHW), Non-Hispanic Black (NHB), and Hispanic. However, because there were only a small number of cases of American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and Asian/Pacific Islander, they were only used to calculate the variables for all races/ethnicities22. The identification of HL patients was conducted using Lymphoid Neoplasm Recode 2021 Revision23, which is the preferred classification system according to SEER 2224: 1(a). classical Hodgkin lymphoma (ICD-O-3 histologic codes 9650–9655, 9661–9667), 1(a)1. lymphocyte-rich/mixed cell/lymphocyte depleted (ICD-O-3 histologic codes 9651–9655), 1(a)2. nodular sclerosis (ICD-O-3 histologic codes 9663–9667), 1(a)3. classical Hodgkin lymphoma, NOS (ICD-O-3 histologic codes 9650, 9661–9662), and 1(b). nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (ICD-O-3 histologic code 9659).

Statistical analysis

The study employed the SEER 22 Research Limited-Field Data with Delay-Adjustment database from 2000 to 202019, which was acquired from SEER*Stat, version 8.4.1.225. They were used for the computation of the age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) with delay adjustment. The aim of modeling reporting delay is to incorporate anticipated future data modifications26. The revised counts, along with the corresponding delay model, can be utilized to identify present cancer patterns accurately26. Only patients with cancer with documented age at diagnosis were included. Afterward, the delay model was utilized, including correction factors for variables such as cancer site, registry, age, race/ethnicity, and the year of diagnosis27,28. The ASIR of HL subtypes was determined using the SEER 22 Research Limited-Field Data database for the years 2000 to 202019. The data was collected using SEER*Stat, version 8.4.1.225. The Tiwari method was employed to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the ASIRs. The US 2000 standard population was used. The corresponding 95% CI29 was also determined using the mentioned software25.

The estimation of APCs and AAPCs30 was conducted using the Joinpoint Regression Program, version 5.0.231. This involved applying joinpoint regression modeling, as well as parallelism and comparability tests32 to ASIRs33. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2020 incidence data could be subject to under-ascertainment and diagnostic delay bias resulting from healthcare access disruptions. Therefore, 2020 was excluded from the joinpoint trend models and displayed separately in the figures. The APCs were calculated using the most accurate least-squares regression lines that were fitted to the natural logarithm of the ASIR, using the year of diagnosis as an independent variable. The minimum number of observations required for a joinpoint is two, and the minimum number of observations required from the joinpoint to either end of the data is also two. The selection of models was conducted using the weighted Bayesian Information Criteria technique34. The 95% CIs of AAPCs was calculated using the empirical quantile approach35. The parallelism test was utilized to conduct a pairwise comparison in order to assess whether the trends of the two groups exhibited similarity within a period of time32. A pairwise comparison was conducted to ascertain whether the rates of the two groups remained the same throughout time.

Results

Hodgkin lymphoma

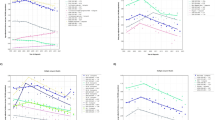

Between 2000 and 2019, there were a total of 10,007 cases of HL in the US among individuals aged 0–19 years. CHL was the most commonly reported subtype (92.98%). Most of these cases were identified among NHW (53.28%), with the highest incidence among individuals aged 15–19 (66.35%). None of the sexes showed significant changes in AAPCs (Table 1; Fig. 1A, B and C, and 1D).

In the more recent period from 2015 to 2019, there were 2,528 cases of HL in pediatrics. Similarly, most cases were observed among NHWs (55.06%) and individuals aged 15 to 19 years (64.88%). During this period, the ASIR per 100,000 population was 1.31 (1.24, 1.38) for males and 1.21 (1.14, 1.28) for females. NHW males reported the highest ASIR among all races and ethnicities at 1.55 (1.44, 1.67) (Table S1). Information regarding the identical coincidence and parallel tests can be found in Table S2 and Table S3, respectively. The results for males and females are provided in the Appendix.

Across pediatric age groups from 0 to 4 through 15–19 years, incidence rates of HL increased with age for both males and females, peaking in the 15–19 cohort (Fig. 2). Temporal trends over 2000–2019, however, showed no significant changes in AAPCs for either sex.

There were no significant changes in the ASIR of pediatric HL across all races/ethnicities in both sexes within all age groups (percent change (PC): -3.11% [-15.33, 9.11]) and for males (PC: 0.05% [-17.02, 17.12]) and females (PC: -6.79% [-24.24, 10.67]) from 2019 to November 2020 (Table 2).

Classical HL (CHL)

From 2000 to 2019, there were 9,305 CHL cases in all age groups in the US. The majority of cases were males (51.78%), NHWs (57.30%), and between 15 and 19 years (66.35%). The ASIR per 100,000 population was 1.16 (1.13, 1.19) for males and 1.13 (1.10, 1.16) for females. The AAPCs for males and females were − 0.59% (− 1.34, 0.15) and − 0.13% (− 0.81, 0.54), respectively (Table 3, Figure S1, Figure S2, and Figure S3).

There was an increasing trajectory in overall incident cases and delay-adjusted incidence rates of CHL in males and females from ages < 4 to 15–19. Females had a lower incidence rate under 14 years; however, in the 15–19 age group, females exhibited a higher incidence rate compared to male (Figure S4).

Lymphocyte-rich/mixed cell/lymphocyte-depleted hodgkin lymphoma (LR/MC/LD HL)

Over 2000–2019, there were a total of 1,040 cases of LR/MC/LD HL in the US across all age groups. The majority of cases were observed in males (68.56%), NHWs (45.38%), and individuals aged 15 to 19 years (48.95%). The ASIR per 100,000 population was 0.17 (0.16, 0.19) for males and 0.08 (0.07, 0.09) for females. Hispanic males had the highest ASIR (0.21 [0.19, 0.24]). The AAPC for males and females were − 1.03% (− 2.73, 0.62) and 1.00% (− 2.18, 4.42), respectively. NHW males experienced the only significant decline in ASIRs from 2000 to 2019 (AAPC: − 1.93% [− 3.99, − 0.06]) (Table 4, Figure S5, Figure S6, and Figure S7).

There was a rise in the incident cases and rates of LR/MC/LD HL in both sexes. Males had a higher incidence rate compared to females (Figure S8).

Nodular sclerosis hodgkin lymphoma (NSHL)

Between 2000 and 2019, there were 6,631 cases of NSHL in among individuals aged 0–19 years in the US. The majority of the cases were females (52.06%), NHWs (60.71%), and between 15 and 19 years old (69.25%). The ASIR per 100,000 population was 0.76 (0.74, 0.79) for males and 0.87 (0.84, 0.90) for females. Both sexes experienced a significant decline in ASIRs over 2000–2019 (AAPC: − 1.75% [− 2.84, − 0.73] for males and AAPC: − 1.37 [− 2.17, − 0.59] for females). NHW females had the highest ASIR (1.10 [1.05, 1.15]). Hispanic males exhibited the greatest decline in ASIRs between 2000 and 2019 (− 2.43% [− 4.44, − 0.46]) (Table 5, Figure S9, Figure S10, and Figure S11).

Both sexes showed a consistent and substantial incline in incident cases and rates from < 4 to 15–19 years. Notably, unlike those < 9 years old, females displayed a higher incidence rates compared to males in the 10–14 and 15–19 age groups (Figure S12).

Classical hodgkin lymphoma not otherwise specified (CHL-NOS)

From 2000 to 2019, there were 1,634 CHL-NOS cases in all age groups in the US. The majority of cases were males (56.67%), NHWs (51.04%), and aged 15–19 years (65.67%). The ASIR per 100,000 population was 0.22 (0.21, 0.24) for males and 0.18 (0.17, 0.19) for females. Hispanic males had the highest reported ASIR (0.23 [0.20, 0.26]). Both sexes experienced an increase in ASIRs between 2000 and 2019 (AAPC: 3.93% [2.78, 5.31] for males and AAPC: 5.68% [4.65, 6.91] for females) (Table 6, Figure S13, Figure S14, and Figure S15).

The incident cases and rates of CHL-NOS increased with advancing age in both males and females (Figure S16).

Nodular lymphocyte prominent hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL)

Over 2000–2019, there were 702 cases of NLPHL in the US across all age groups. The majority of cases were observed in males (80.91%), NHWs (59.26%), and cases between 15 and 19 years (44.73%). The ASIR per 100,000 population was 0.14 (0.13, 0.15) for males and 0.03 (0.03, 0.04) for females. NHW males had the highest ASIR (0.17 [0.15, 0.19]). Both sexes experienced a significant increase in ASIRs over 2000–2019 (AAPC: 6.01% [4.71, 7.61] for males and AAPC: 7.19% [4.85, 10.79] for females) (Table 7, Figure S17, Figure S18, and Figure S19).

Both sexes exhibited increases in incident cases and rates with ageing and males had higher values than females for NLPHL (Figure S20).

Discussion

Summary of major findings

Utilizing the SEER database, this analysis provides a thorough, up-to-date, and population-based assessment of pediatric HL incidence trends in the US from 2000 to 2020. Overall, no significant fluctuations were observed in the incidence of pediatric HL throughout the period spanning from 2000 to 2019. The predominant subtype of HL reported was CHL, accounting for 92.98% of cases. The incidence rates consistently increased across both sexes, peaking within the 15–19 age group, with a notably higher incidence rate observed in females compared to males within this age bracket. This pattern was observed in the overall and CHL subtype populations. Overall, NHW individuals had higher incidence rates of pediatric HL and demonstrated a higher rate in both sexes of NHW ethnicity. NHBs demonstrated a significant increase in incidence rates of all subtypes in the period of 2000–2008. Subtype-specific analyses revealed distinct trends: nodular sclerosis subtype demonstrated a decline, while NLPHL subtype showed the highest AAPC. All groups displayed increased incidence rates for classic HL, NOS.

Overall trends

The incidence trend of HL in children in the US has shown variations in recent years. HL represents approximately 4% of childhood malignancies and 15% of adolescent malignancies, with bimodal incidence peaks in adolescent and adult age ranges36. Our results suggest that no significant changes were seen in the overall incidence trend of pediatric HL over 2000–2019. This stability has also been reflected in previous studies on global data36,37,38. Some global studies, however, indicated a rise in HL incidence, with the most notable increase observed among females, individuals of Asian descent, and younger age groups14. Another investigation using the same dataset, targeting the burden and trends of cancers among children under five years old worldwide, regionally, and nationally, found that China exhibited the highest number of incident cases for HL. Moreover, the study noted a 31.8% decrease in overall HL incidence from 1990 to 2019, leading to a subsequent decline in the burden of this cancer39. The discrepancy in the observed trends highlights the need for further investigation into potential contributing factors.

Age and sex patterns

Overall, incidence rates rose with advancing age, reaching their highest levels in the 15–19-year age group for both sexes. Despite these age-related gradients, calendar-time AAPCs remained stable, indicating no significant changes in overall pediatric HL rates from 2000 to 2019. Notably, females within this age bracket demonstrated a higher incidence rate than males. CHL exhibited the same patterns, with both sexes displaying a consistent increase in incidence rates, peaking in the 15–19 age group, and females exhibiting a lower incidence rate in the under-14 age group. A previous study on the SEER data by Percy et al. has also established that boys under the age of 15 years exhibited a higher incidence of HL, with boys under five years old experiencing up to five times higher incidence rates than girls of the same age group40. There is limited literature exploring the factors contributing to the sex difference in pediatric HL, with existing studies primarily attributing this phenomenon to the higher prevalence of the Epstein-Barr virus in boys under age 15 years41. One factor contributing to the higher incidence in the 15–19 age group for both sexes can be geography and specific socioeconomic factors. Congruent with our results, a previous study on the SEER database stated that in economically advantaged countries such as the US and Europe, HL primarily affects older adolescents and young adults, with a secondary peak observed in older adults42. Moreover, a recent study in 2019 by Siegel et al. reported that lymphomas are the most prevalent cancer types among adolescents, accounting for around 21% of new cancer diagnoses in individuals aged 15 to 19 years in these regions. Notably, HL constitutes approximately two-thirds of these adolescent lymphoma cases43. Another study conducted by Huang et al. utilizing global data reported that the more pronounced rise in HL incidence among female subjects could potentially be attributed to variations in the increasing trend of obesity and metabolic diseases in the female population14.

COVID-19 and pediatric HL

Our analysis only assessed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric HL incidence during the early part of the pandemic. Due to the availability of data only through November 2020—representing less than one full year of the pandemic—we can only describe trends in the early pandemic period and cannot draw firm conclusions about longer-term effects. In this interval, our analysis revealed no significant change in ASIR across all races/ethnicities and both sexes in any pediatric age group. A study conducted by Pelland-Marcotte et al. investigating the incidence of childhood cancer in Canada amidst the COVID-19 pandemic found no statistically significant alteration in the incidence of childhood cancers. Similarly, there were no notable changes observed in the proportion of children participating in clinical trials, those presenting with metastatic disease, or those experiencing early mortality during the initial nine months of the pandemic44. Another study conducted by Howlader et al. based on the SEER 22 examining the influence of COVID-19 on cancer incidence rates revealed that for individuals aged 0–19, the combined incidence rate for all cancers was 21.2 in April 2019, contrasting with a rate of 14.0 in April 2020. However, the study did not report HL incidence separately45.

Histological subtypes

Our results demonstrated that the prevailing subtype of HL in the US was CHL. A single-institution series from one region, comprised predominantly of adult patients and not derived from a population-based registry have also indicated that CHL constitutes approximately 90% of cases, with NLPHL representing most of the remaining cases46. However, it is essential to acknowledge that the distribution of histologic subtypes of CHL may vary depending on geographic location, socioeconomic factors, race/ethnicity, and age. This study did not assess geographic location or socioeconomic status. Nevertheless, notable findings emerged regarding the disparity in incidence rates among different subtypes across diverse age groups and ethnicities, such as classic and NLPHL subtypes, both having the highest ASIR among NHW males. The nodular sclerosis subtype displayed a declining incidence rate, while the NLPHL subtype exhibited the highest AAPC. This decline may, in part, reflect changes in diagnostic and coding practices over time. As immunohistochemical panels and World Health Organization classification updates were adopted, some cases previously assigned to nodular sclerosis may have been reclassified into other subtypes or NOS categories. Enhanced histopathologic review and registry coding specificity could therefore artifactually lower recorded NSHL incidence. A study by Glaser et al. on the SEER data from 1992 to 2011 reported that after 2007, nodular sclerosis rates experienced an annual decline of 5.9%, with differences observed among sexes, age groups, and races/ethnicities36. This study suggests that the decline in the predominant nodular sclerosis category may be attributed to environmental shifts promoting early-life social isolation. Such isolation has been recognized as a factor influencing the risk of HL in young adults47.

NLPHL constitutes around 5% of diagnosed HL cases48. Prior research indicates that NLPHL incidencehas remained steady at roughly eight to nine cases per 10,000,000 individuals annually in the US and Europe, although there might be an increasing trend in children, congruent with the results of our study49,50. A regional, retrospective study of 80 adult patients (> 20 years) in south-east Netherlands stated that the incidence of NLPHL increased from six new patients from 1990 to 1995 to 38 patients in 2006–2010. However, this small, non-national cohort did not review cases coded as other or unspecified lymphomas, some of which may have represented undiagnosed NLPHL51. Advancements in immunohistochemistry technology and its increased accessibility may have played a role in the observed rise in incidence in the Netherlands51.

Previous literature stated that in the US, NLPHL exhibited a higher prevalence among Black Americans compared to White Americans, setting it apart from classic HL49. However, our results showed that NHW males exhibited the highest incidence rate among both subtypes during the last two decades. Black patients with NLPHL tend to be younger, more often female and have different primary disease sites compared to white patients52. Additionally, black patients exhibited unfavorable socioeconomic characteristics, delayed time to therapy initiation, and a higher rate of no treatment for early-stage disease53. These differences in clinical presentation suggest a complex interplay of race-specific and sex-specific susceptibility factors for NLPHL.

A significant increase in classic HL-NOS incidence rates was observed over the study period. Specific studies addressing this trend in the literature still need to be included. The previously mentioned study by Glaser et al. reported that a notable rise in NOS rates across various patient groups was observed36. Age-specific rates of NOS during 2007–2011 closely mirrored mixed cellularity rates from 1992 to 1996 rather than those from 2007 to 2011, indicating a concerning trend in misclassification of subtypes as NOS. Among reviewed pathology reports, some addressed classification choice, with explanations provided, insufficient biopsy material cited, or specific subtype information missing. This paper suggested that the observed long-term increases in NOS likely signify shifts in diagnostic and/or classification methodologies36. The findings highlight the need for implementation of programs to improve the cancer registries and pathology reports in next years.

Race/ethnicity

Our findings indicated that, in general, NHW children exhibited higher incidence rates of pediatric HL. A SEER study conducted by Evans et al., analyzing data from 1992 to 2007 among individuals aged 10 to 79 years, indicated that Whites demonstrated a bimodal age-specific incidence pattern similar to that of Asian/Pacific Islanders. In contrast, Blacks and Hispanics did not exhibit this bimodal pattern. In the mentioned study, in the 10–19 age group, NHW individuals exhibited the highest initial age-specific incidence rate, approximately 2.5 per 100,000 persons54. It has been suggested that socioeconomic status may play a role in influencing incidence rates, as individuals residing in higher socioeconomic status environments have been observed to have a greater risk of HL54. Studies also suggested that NHW children in the US had higher rates of HL, possibly due to associations with maternal birthplace, birth weight, and parental age55.

Limitations and strengths

There are some limitations to this study: (1) The analysis did not include significant risk factors for HL, such as the prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus infection, HIV/AIDS, and autoimmune diseases; (2) Misclassifying cases or histological subtypes within the database could lead to inaccuracies in the reported incidence rates; and (3) Findings from the SEER database may not apply to other populations or healthcare settings, limiting the study’s external validity.

The present study’s strengths lie in its utilization of a robust, nationally representative database, offering high-quality data to examine ASIRs, APCs, and AAPCs of pediatric HL histotypes across diverse racial and ethnic groups in the US over a twenty-year period. Furthermore, the study adhered to widely recognized and precise histologic definitions to accurately classify different histologic types of this cancer.

Conclusions

The overall age-standardized incidence of pediatric HL in the US remained stable between 2000 and 2019, with no significant fluctuations observed in the general pediatric population. However, distinct patterns emerged in subgroup and subtype analyses, including rising rates in certain age and racial/ethnic groups. These findings underscore the need for further research into the underlying factors driving these specific trends.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available at https://seer.cancer.gov/data-software/.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73(1), 17–48 (2023).

Hsu, J. L. & Glaser, S. L. Epstein-barr virus-associated malignancies: Epidemiologic patterns and etiologic implications. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 34(1), 27–53 (2000).

Clifford, G. M. et al. Cancer risk in the Swiss HIV cohort study: Associations with immunodeficiency, smoking, and highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 97(6), 425–432 (2005).

Fallah, M. et al. Hodgkin lymphoma after autoimmune diseases by age at diagnosis and histological subtype. Ann. Oncol. 25(7), 1397–1404 (2014).

Sud, A., Hemminki, K. & Houlston, R. S. Candidate gene association studies and risk of hodgkin lymphoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hematol. Oncol. 35(1), 34–50 (2017).

Strongman, H., Brown, A., Smeeth, L. & Bhaskaran, K. Body mass index and hodgkin’s lymphoma: UK population-based cohort study of 5.8 million individuals. Br. J. Cancer. 120(7), 768–770 (2019).

Triebwasser, C. et al. Birth weight and risk of paediatric hodgkin lymphoma: Findings from a population-based record linkage study in California. Eur. J. Cancer. 69, 19–27 (2016).

Ward, E., DeSantis, C., Robbins, A., Kohler, B. & Jemal, A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J. Clin. 64(2), 83–103 (2014).

Wu, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national childhood cancer burden, 1990–2019: an analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2019. J. Adv. Res. 40, 233–247 (2022).

Ries, L. A. K. C. et al. SEER cancer statistics review: 1973–1994. NIH publ no. 97-2789. (Bethesd, 1997).

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figs. 2020 2021. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2020.html.

Siegel, D. A. et al. Counts, incidence rates, and trends of pediatric cancer in the United states, 2003–2019. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 115 (11), 1337–1354 (2023).

Marcotte, E. L., Domingues, A. M., Sample, J. M., Richardson, M. R. & Spector, L. G. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric cancer incidence among children and young adults in the United States by single year of age. Cancer 127(19), 3651–3663 (2021).

Huang, J. et al. Incidence, mortality, risk factors, and trends for hodgkin lymphoma: a global data analysis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 15(1), 57 (2022).

Landgren, O. et al. Autoimmunity and susceptibility to hodgkin lymphoma: a population-based case-control study in Scandinavia. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 98(18), 1321–1330 (2006).

Taj, T. et al. Long-term residential exposure to air pollution and hodgkin lymphoma risk among adults in denmark: A population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 32(9), 935–942 (2021).

Surveillance EaERS. About the SEER Program - SEER. Retrieved Jun 11. from (2023). https://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html. 2023.

databse TNCIsS. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and & Results, E. (SEER) Program (http://www.seer.cancer.gov/) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER Research Limited-Field Data with Delay-Adjustment, 22 Registries, Malignant Only, Nov 2022 Sub (2000–2020) - Linked To County Attributes - Time Dependent (1990–2021) Income/Rurality, 1969–2021 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released April 2023, based on the November 2022 submission.

databse TNCIsS. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (http://www.seer.cancer.gov/) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER Research Limited-Field Data, 22 Registries, Nov 2022 Sub (2000–2020) - Linked To County Attributes - Time Dependent (1990–2021) Income/Rurality, 1969–2021 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released April 2023, based on the November 2022 submission.

SEER. SEER Research Data Agreement. (n.d.). SEER & Retrieved Jun 11, from (2023). https://seer.cancer.gov/data-software/documentation/seerstat/nov2022/seer-dua-nov2022.html.

The National Cancer Institute. Impact of COVID on 2020 SEER Cancer Incidence Data. (2023).

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER). Race and Hispanic Ethnicity Changes 2024. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/variables/seer/race_ethnicity/.

National Cancer Institue. Lymphoid Neoplasm Recode 2021 Revision 2024. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/lymphomarecode/lymphoma-2021.html; https://seer.cancer.gov/lymphomarecode/lymphoma-2021revision.xlsx

National Cancer Institue. Lymphoma Subtype Recodes 2024. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/lymphomarecode/

SEER. Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software (seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) version 8.4.1.2.

Clegg, L. X., Feuer, E. J., Midthune, D. N., Fay, M. P. & Hankey, B. F. Impact of reporting delay and reporting error on cancer incidence rates and trends. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 94(20), 1537–1545 (2002).

Technical Notes - Reporting Delay. In (eds Altekruse, S. et al.) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2007, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website 12–16. (2010).

The National Cancer Institute. Development of the Delay Model 2023. Available from: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/delay/model.html

Tiwari, R. C., Clegg, L. X. & Zou, Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 15(6), 547–569 (2006).

Clegg, L. X., Hankey, B. F., Tiwari, R., Feuer, E. J. & Edwards, B. K. Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat. Med. 28(29), 3670–3682 (2009).

Institute, N. C. Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 5.0.2 Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute (2023).

Kim, H. J., Fay, M. P., Yu, B., Barrett, M. J. & Feuer, E. J. Comparability of segmented line regression models. Biometrics 60(4), 1005–1014 (2004).

Kim, H. J., Chen, H. S., Byrne, J., Wheeler, B. & Feuer, E. J. Twenty years since joinpoint 1.0: Two major enhancements, their justification, and impact. Stat. Med. 41(16), 3102–3130 (2022).

The National Cancer Institute. Weighted BIC (WBIC). (2023). Available from: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/help/joinpoint/setting-parameters/method-and-parameters-tab/model-selection-method/weighted-bic-wbic.

Kim, H. J. et al. Improved confidence interval for average annual percent change in trend analysis. Stat. Med. 36(19), 3059–3074 (2017).

Glaser, S. L., Clarke, C. A., Keegan, T. H., Chang, E. T. & Weisenburger, D. D. Time trends in rates of hodgkin lymphoma histologic subtypes: True incidence changes or evolving diagnostic practice?? Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 24 (10), 1474–1488 (2015).

Zhou, L. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of hodgkin lymphoma from 1990 to 2017: Estimates from the 2017 global burden of disease study. J. Hematol. Oncol. 12 (1), 107 (2019).

Rico, J. & Tebbi C. Hodgkin lymphoma in children: A review. Austin J. Pediatr. 1(3), 7 (2014).

Ren, H. M. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of Cancer in children younger than 5 years, 1990–2019: analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. Front. Public. Health 10, 910641 (2022).

Percy, C. L. S. M. & Linet, M. Lymphomas and reticuloendothelial neoplasms. In (eds Ries, L. A. S. M., Gurney, J. G. et al.) Cancer Incidence and Survival among Children and Adolescents: United States SEER Program, 1975–1995 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, 1999).

Maggioncalda, A. et al. Clinical, molecular, and environmental risk factors for hodgkin lymphoma. Adv. Hematol. 2011, 736261 (2011).

Ries, L. A. K. C. et al. (eds) SEER cancer Statistics Review: 1973–1994. NIH Publ No. 97-2789 Ed (National Cancer Institute, 1997).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 69 (1), 7–34 (2019).

Pelland-Marcotte, M. C. et al. Incidence of childhood cancer in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cmaj 193(47), E1798–e806 (2021).

Howlader, N. et al. Cancer and COVID-19: US cancer incidence rates during the first year of the pandemic. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 116(2), 208–215 (2024).

Laurent, C. et al. Prevalence of common non-Hodgkin lymphomas and subtypes of hodgkin lymphoma by nodal site of involvement: A systematic retrospective review of 938 cases. Med. (Baltim). 94(25), e987 (2015).

Chang, E. T. et al. Childhood social environment and hodgkin’s lymphoma: New findings from a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 13(8), 1361–1370 (2004).

Swerdlow, S. H. C. E. et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues 4th edn. (International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC, Lyon, 2017).

Morton, L. M. et al. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the united states, 1992–2001. Blood 107(1), 265–276 (2006).

Sant, M. et al. Incidence of hematologic malignancies in Europe by morphologic subtype: Results of the HAEMACARE project. Blood 116(19), 3724–3734 (2010).

Strobbe, L. et al. A 20-year population-based study on the epidemiology, clinical features, treatment, and outcome of nodular lymphocyte predominant hodgkin lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 95(3), 417–423 (2016).

Olszewski, A. J., Shrestha, R. & Cook, N. M. Race-specific features and outcomes of nodular lymphocyte-predominant hodgkin lymphoma: analysis of the national cancer data base. Cancer 121(19), 3472–3480 (2015).

Park, E. R., Japuntich, S. J., Traeger, L., Cannon, S. & Pajolek, H. Disparities between Blacks and Whites in tobacco and lung cancer treatment. Oncologist 16(10), 1428–1434 (2011).

Evens, A. M., Antillón, M., Aschebrook-Kilfoy, B. & Chiu, B. C. Racial disparities in hodgkin’s lymphoma: A comprehensive population-based analysis. Ann. Oncol. 23(8), 2128–2137 (2012).

Graham, C. et al. Hispanic ethnicity differences in birth characteristics, maternal birthplace, and risk of early-onset hodgkin lymphoma: A population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 31(9), 1788–1795 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the National Institute of Cancer staff and its collaborators of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) who prepared the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SEM and SAN designed the study. SEM analyzed the data and performed the statistical analyses. S.E.M., H.G., M.N., A.A., Z.Y., and S.A.N. drafted the initial manuscript. S.E.M., H.G., M.N., A.A., Z.Y., and S.A.N. critically edited and revised the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the drafted manuscript for critical content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mousavi, S.E., Najafi, M., Aslani, A. et al. Population based analysis of twenty year incidence trends of pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States. Sci Rep 15, 22634 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07472-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07472-x