Abstract

Enhancing oil recovery in clay-rich sandstone reservoirs remains a critical challenge, particularly for heavy oil extraction. Although low salinity water flooding has been widely investigated, the synergistic potential of combining cationic surfactants, such as cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), with low salinity water to improve emulsion stability and, consequently, oil recovery in such reservoirs has received limited attention. This study pioneers a novel experimental approach to investigate the simultaneous impact of CTAB and smart water flooding on heavy oil recovery in clay-rich systems. By exploring the interplay between ion-tuned water and CTAB, we uncover new insights into their combined influence on emulsion behavior, interfacial properties, and oil mobilization. In this regard, the interfacial tension (IFT) and zeta potential values for sulfate-enriched seawater containing CTAB were approximately 15.2 mN/m and 6.4 mV, respectively, lower than those of magnesium-enriched seawater. This indicates enhanced interfacial activity and clay surface modification. Emulsion stability tests revealed that reduced ion concentrations, especially in sulfate-enriched aqueous solutions, significantly enhanced emulsion stability. This was illustrated by an extended emulsion separation time of approximately 70 min under these conditions. Moreover, fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis of the separated oil phases from the emulsion revealed a notable reduction in polar components in oil exposed to cation-rich water, while non-polar components were more prevalent in oil contacted with sulfate-enriched water. The contact angle measurements indicated that sulfate-enriched seawater (SW2d.2SO4) exhibited the lowest contact angle (31°) among all brine solutions. These findings provide insights into the mechanisms of emulsion stabilization and the role of oil components, offering a transformative perspective on optimizing smart water flooding with cationic surfactants for improved heavy oil recovery in clay-rich reservoirs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, smart water flooding (also referred to as ion-tuned water or low-salinity water injection) has gained significant attention as an environmentally and economically viable enhanced oil recovery (EOR) technique for sandstone reservoirs1,2,3. This method involves injecting brine solutions with optimized ionic compositions, often including sulfate (SO42−), calcium (Ca2+), and magnesium (Mg2+), to modify the wettability of reservoir rocks and enhance oil displacement efficiency4. The interaction of these ions with the mineral surfaces in sandstone reservoirs can promote the desorption of oil components, thereby improving recovery rates5. However, the success of smart water flooding is highly influenced by several factors, including the reservoir’s mineralogical composition, particularly the presence of clay particles, the type of ions and their concentration in smart water, and polar components of oil, which can significantly affect fluid flow and heavy oil recovery dynamics6,7.

Despite its potential benefits, smart water flooding may have unintended consequences in sandstone reservoirs, particularly emulsification. Emulsification plays a dual role in oil recovery processes. While it can enhance oil displacement in the reservoirs by improving sweep efficiency8, it may introduce operational challenges that vary significantly depending on emulsion type (oil-in-water or water-in-oil)9,10,11. Specifically, emulsification can adversely affect production by increasing the viscosity of the produced fluids12, complicating phase separation, and causing operational challenges such as pipeline blockages and reduced oil quality. These effects impose significant economic and environmental burdens, particularly in surface facilities where costly oil-water separation is required13,14. Therefore, developing strategies to control water-in-oil emulsion formation and stabilize production processes represents a critical need for sandstone reservoirs undergoing smart water flooding.

One significant issue is the exacerbation of emulsion formation due to the interaction of injected brine with clay particles and heavy oil components. Clay minerals, such as kaolinite, illite, and montmorillonite, are commonly found in sandstone reservoirs and play a crucial role in interactions with heavy oil15. These particles can adsorb polar components of crude oil, such as asphaltene molecules, forming stable emulsions16,17.

Asphaltene molecules are fundamental to creating and stabilizing emulsions, especially in systems involving oil and water18,19. Asphaltenes, characterized by their high molecular weight and complex polycyclic aromatic structures, contain polar and non-polar functional groups that allow them to function as natural surfactants9,20. These molecules can accumulate at the interface between oil and water, lowering the interfacial tension21. Literature surveys have demonstrated that a significant fraction of asphaltenes adsorb at the interface, forming a rigid film through an irreversible mechanism.

In this regard, Tajikmansori et al. demonstrated that the interfacial behavior of crude oil is significantly influenced by the molecular structure of asphaltenes and their electrostatic properties22,23. In addition, Liang et al. suggested that the concentration of asphaltenes and the NSO concentration can influence the properties of the oil-water interface24. Hence, investigating the influence of oil components on emulsion properties is of critical importance.

Moreover, numerous studies have been conducted to explore the effects of ion-tuned water and clay particles on the properties of the emulsion phase. Mahdavi et al. examined the simultaneous influence of clay particles and ion-tuned water on emulsion stability. They demonstrated that the interaction between high-salinity water or ion-tuned water and crude oil, particularly in the presence of clay particles, can result in the generation of highly stable emulsions6,25. In another work, Demir et al. emphasized that the synergistic presence of clay particles and ions can reduce interactions between the aqueous phase and asphaltenes, resulting in the formation of significant aggregates composed of asphaltene-clay mixtures26. Consequently, evaluating the interaction of asphaltene, ions, and clay is essential in controlling the production of water-in-oil emulsions.

The injection of surfactants, such as cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), has demonstrated significant potential for enhancing oil recovery through three key mechanisms: (1) addressing emulsion-related challenges in oil recovery, (2) inducing wettability alteration (water-wet) in reservoir rocks27, and (3) effectively reducing oil-water interfacial tension28,29,30. CTAB’s unique amphiphilic structure, consisting of a positively charged head group and a long hydrophobic tail, allows it to interact with both polar, such as asphaltene molecules, and non-polar components in the reservoir2. CTAB molecules may tend to migrate toward the oil-water interface. They can disrupt existing emulsions and prevent new emulsion formation23,31. It should be noted that their effectiveness is highly dependent on system characteristics, including oil polarity, ionic strength, pH, and the presence of competing surface-active components27,32,33. The impact of CTAB molecules on emulsion formation and stability has been extensively investigated in various studies.

Researchers conducted a variety of experimental techniques to explore the interactions between surfactants and crude oil components, including Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy34, emulsion stability and interfacial tension (IFT) measurements35, zeta potential, and contact angle analysis36, among others. For example, Seng et al. explored the interactions between heavy oil and different surfactants by employing a combination of core flooding experiments, zeta potential measurements, and optical tests. They concluded that the presence of saturates in crude oil significantly contributed to the formation of smaller, more uniformly dispersed emulsion droplets29.

In a related study, Koreh et al. examined the interfacial performance of different surfactant types and their interactions with crude oil properties. They demonstrated that the type of surfactant has a considerable impact on emulsion formation and stability37. Additionally, Javadi et al. investigated the synergistic effects of CTAB molecules and low-salinity water through a series of experimental tests. Their study demonstrated that CTAB molecules adsorb at the oil/brine interface by embedding their hydrophobic tails into the oil phase. They emphasized that the efficiency of this mechanism depends on both the surfactant concentration and the ionic strength of the brine38. Zallaghi et al. evaluated the synergistic effects of combining surfactants with smart water. Their results indicated that the injection of ion-tuned water-surfactant aqueous phase significantly enhanced recovery factors39.

It is also well-established that surfactant sorption is strongly influenced by factors such as the simultaneous impact of ions and rock mineralogy during smart water flooding in sandstone reservoirs40. Hou et al. demonstrated that surfactant adsorption on sandstone surfaces reduced the asphaltene molecules’ size, thereby increasing the rock’s water-wet characteristics41. In another work, they asserted that synthesized gemini surfactants can enhance oil recovery through significant reduction of oil-water interfacial tension and generation of favorable emulsions42. According to the experimental study by Liu et al., the presence of CaCl2 in solutions significantly influenced the adsorption of surfactants on clay surfaces43.

Besides, investigations by Khezerloo-ye Aghdam et al. clarified that when CTAB is introduced to low-salinity waterflooding systems in clay-rich sandstones, the resulting solution: (i) intensifies electrostatic attraction at fluid-rock interfaces, while (ii) simultaneously modifying wettability characteristics through distinct adsorption mechanisms - binding to rock matrices and interacting with acidic components in the crude oil32. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation is crucial to elucidate the interactions between CTAB, oil components, ions in ion-tuned water, and clay in the emulsion phase. Such understanding could lead to the development of effective strategies to address the challenges posed by water-in-heavy oil emulsions.

In this study, the synergistic interactions between clay particles, ions in smart water, CTAB surfactant, and heavy component of crude oil components was conducted from a new approach. A novel experimental methodology was developed to precisely evaluate the individual and combined roles of these components, including the molecular structure of oil componets, ion-tuned water chemistry, CTAB, and clay. A comprehensive suite of tests—including contact angle measurements, zeta potential analysis, interfacial tension (IFT) determination, and emulsion stability assessment—was employed to explore: (1) the combined effects of divalent cations, anions, and CTAB on IFT; (2) the synergistic interactions between CTAB cationic surfactant and ion-tuned water solutions on zeta potential and wettability alteration; and (3) the influence of ion and CTAB concentration variations, in the presence of clay particles, on emulsion stability. Furthermore, FTIR analysis was utilized to study the contributions of polar and non-polar crude oil components to the phenomena at the oil-water interface.

Materials and methods

Materials

Oil sample

The crude oil sample used in this experimental study was sourced from an Iranian oil field. Its characteristics and SARA (Saturates, Aromatics, Resins, and Asphaltenes) analysis are detailed in Table 1. It is particularly noteworthy that the physicochemical properties of this crude oil align closely with characteristic heavy oil reported in prior studies44,45,46. To assess the stability of heavy oil, the Colloidal Instability Index (CII) was calculated using Eq. 1. Notably, a CII value greater than 0.9 or less than 0.7 indicates the presence of unstable asphaltenes in the crude oil47.

Aqueous phase

This enabled the study of the simultaneous effects of the interactions among clay particles, CTAB, and ion-modified water. Persian Gulf seawater was utilized as the base fluid to prepare the smart water. To avoid salt precipitation during the subsequent increase in ion concentrations, the seawater was first diluted to 50% by the gradual addition of deionized water48,49. Subsequently, the concentrations of magnesium, calcium, and sulfate ions were increased to two and four times their original salinity in seawater. Aqueous solutions, including seawater (SW), two-times diluted seawater (SW2d), and ions-rich seawater, were mixed with the cationic surfactant cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB). CTAB, a cationic surfactant with a critical micelle concentration (CMC) of approximately 0.386 g/L and a molecular weight (MW) of 348.47 g/mol, was utilized. The compositions of all aqueous solutions are provided in Table 2. The salts and surfactants used in this experimental study were procured from Merck Company, Germany, with a purity of > 99. It is important to note that the concentration of CTAB and clay particles remained constant, while the total dissolved solids (TDS) represent the ion concentration in the aqueous phases.

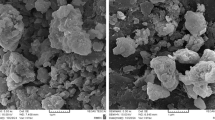

Clay particle

It has been suggested that clay minerals with high Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC), such as kaolinite, play a significant role in smart water flooding processes7,50,51. Kaolinite is widely recognized as a non-swelling alumina-silicate clay, with the approximate chemical formula Al2Si2O₅(OH)452. For this experimental study, kaolinite was selected to examine the interactions among clay particles, CTAB, ions, and crude oil components. The experiments were conducted using kaolinite powder with an average particle size of 1.1 μm. The mineralogical composition of the kaolinite was analyzed using X-ray fluorescence (XRF), and the detailed results are summarized in Table 3.

Method

Sample Preparation

Initially, mixtures of oil and aqueous phase samples (based on Table 2) were prepared in 50 mL volumes at a 60:40 ratio (water: oil) for the tests of the bottle6,53,54,55. Subsequently, an ultrasonic probe was used to disperse the oil in the water phase, facilitating the mixing of the bulk oil in seawater, CTAB, and clay particles. Following the sonication step, the emulsification of the oil and brine was carried out using a magnetic heat stirrer at 1000 rpm for 6 h at 25 °C, resulting in the formation of a homogenized emulsion phase. This emulsion mixture was placed in an oven at 90 °C for 20 days to simulate reservoir conditions. After collecting the emulsion samples, they were transferred to graduated plastic centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for varying durations, with measurements taken at 5-minute intervals. The solutions were monitored every 5 min until complete phase separation was achieved, driven by the centrifugal force. Subsequently, the separated oil phases, water phases, and solid fractions were placed in a dark room at 25 °C for 24 h. The stability of an emulsion under centrifugation was evaluated by measuring the percentage of free oil and solid fractions56.

The oil samples were carefully collected from the top of the bottle for subsequent experiments conducted at 25 °C. To ensure purity, the collected oil was centrifuged twice to eliminate residual water droplets, clay particles, and dissolved gases6,9,12. After the centrifugation step, the oil samples were selected from the tops of the centrifuge vials and named “aged oil-SW”. It is important to note that all experimental tests were repeated at least three times to ensure reproducibility. The sample preparation procedure is illustrated in Fig. 1.

IFT (interfacial tension) measurement

To comprehend interfacial phenomena, it is essential to focus on variations in interfacial tension (IFT). The equilibrium IFT value was examined between crude oil and various aqueous phases using the Pendant Drop method for a more thorough analysis of fluid-fluid interactions25,57. In this method, oil samples are injected through a needle into a cell filled with the target aqueous solution. After allowing the oil-water system to equilibrate, the interfacial tension is calculated by analyzing droplet images with specialized software. The image and schematic of interfacial tension measurement are illustrated in Fig. 2. It should be noted that IFT measurements were performed 3 times, with the mean value reported as the final result.

Zeta potential measurement

The zeta potential of kaolinite particles was identified under controlled experimental conditions, with a temperature of 25 °C and a pressure of 14.7 psi. The pH of the system was maintained at 7 throughout the measurements50,59. A MICROTAC Wave-particle size analyzer was employed to assess the electrophoretic mobility of the kaolinite particles dispersed in various aqueous phases. The electrophoretic mobility values were then converted into zeta potential.

To prepare the samples, a 5% weight% ratio was used, dispersing 5 g of clay in 100 mL of aqueous phase. The mixture was subjected to sonication using an ultrasonic probe to ensure uniform dispersion. Following sonication, the suspension was immediately placed on a magnetic stirrer to maintain homogeneity50,59. The pH of the suspension was carefully adjusted to 7 by adding either 1 M NaOH or 0.1 M HCl, depending on the requirement.

For each sample, the zeta potential was measured five times. The reported zeta potential values represent the average of these five measurements. The measurement error was estimated to be approximately ± 2–3 mV, based on the standard deviation of the five measurements conducted for each sample6,50.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to analyze alteration in the concentration of functional groups of crude and aged oil samples, specifically those separated from the emulsion phase60,61. In this regard, the oil samples were placed on KBr pellets under high pressure for FTIR transmission measurements6,62. The analysis was conducted using a PerkinElmer FTIR spectrometer, which recorded spectra across a wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm− 1. To ensure consistency and comparability, normalization of the FTIR spectra was performed using the peak heights at 2920 cm− 1, corresponding to the C-H stretching vibrations in CH2 structures22. This normalization process allowed for more accurate identification and comparison of functional group alterations in the aged oil samples.

Contact angle measurement

The clay powder was dried in an oven at 80 °C for 24 h to eliminate residual moisture. Subsequently, the dried clay powder was immersed in distilled water for 2 days to ensure complete hydration, a critical step for clay minerals due to their high affinity for water and the need to achieve equilibrium with the aqueous phase63,64,65. The hydrated clay powder was then mixed with crude oil at a mass ratio of 1:2 (clay: oil) to ensure uniform saturation. The mixture was placed in an oven at 80 °C for 5 days to allow the oil to adsorb onto the clay particles. After oil saturation, the clay powder was placed on a paper filter, and a vacuum was applied to remove excess oil, ensuring that only adsorbed oil remained on the clay particles to simulate reservoir conditions. Then, the oil-saturated clay powder was washed with distilled water to eliminate any loosely bound oil.

The samples were dried at 80 °C for 24 h before further analysis. As a result, the dried clay powder was compressed into pellets using a hydraulic press, applying a pressure of 200 kPa.cm⁻² to form pellets with a diameter of 2 cm57,66,67,68. No binding material was used during compression to avoid altering the natural wettability of the clay. The contact angle was measured using the sessile drop method (Fig. 2). A high-resolution camera equipped with a macro lens, a light source, a fluid chamber, and a syringe injection pump were utilized for this purpose. The clay pellets were placed in a chamber filled with distilled water, and a droplet of crude oil was injected onto the pellet surface. This was named as initial contact angle.

The oil-saturated clay powder was divided into several portions and immersed in different aqueous solutions. These samples were placed in an oven at 80 °C for 30 days to simulate long-term exposure to reservoir conditions57,63,64. A portion of the clay powder was investigated every 3 days to monitor changes in wettability, providing secondary contact angle measurements. Images were captured for 1 h to monitor the contact angle over time. Measurements continued until the difference between the last two contact angles was less than 2°, indicating that equilibrium had been reached.

Results

Interfacial tension (IFT)

Interfacial tension is a critical parameter in understanding the behavior of oil-water systems, as it quantifies the force per unit length at the interface between two immiscible fluids and fluid-fluid interaction58,69,70. The IFT is influenced by factors such as the ionic composition of the aqueous phase, the presence of natural surfactants (including asphaltene and resin molecules), and the addition of surfactants like CTAB37,71. In enhanced oil recovery and emulsion stabilization, reducing IFT is desirable as it promotes the formation of smaller droplets and improves oil displacement efficiency57. CTAB plays a significant role in modifying IFT based on previous studies, thereby altering the interfacial properties. In this regard, we measured the IFT of crude oil in various aqueous phases enriched with divalent ions, CTAB molecules and clay particles. The results are presented in Fig. 3.

As can be seen in Fig. 3, the IFT between crude oil and different aqueous phases, including smart water and CTAB solutions, reduced notably. This variation in IFT is strongly influenced by the ionic composition and CTAB concentration of the aqueous solutions, highlighting the critical role of CTAB and electrolyte interactions in modulating interfacial behavior. For instance, the IFT value for the oil-(SW2d.4Mg) system was recorded at approximately 20.5 mN/m, while the IFT for oil-(SW2d.2SO4) was significantly lower at around 5.3 mN/m.

Furthermore, as the concentration of divalent ions decreased, the IFT approached the value observed for SW2d. This trend underscores the significant influence of divalent ions (Mg2+ and sulfate ions (SO42−) concentration on IFT value. Specifically, higher concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ were found to elevate IFT, whereas the presence of SO42− ions contributed to a reduction in IFT.

The variation in IFT values can be attributed to the chemical composition of the aqueous phase and its interaction with crude oil components. Specifically, the irreversible migration of amphiphilic hydrocarbons (including asphaltene molecules) from the oil bulk to the interface is influenced by the surrounding aqueous phase9. Divalent ions such as Ca2+, Mg2+, and SO42− play a more significant role in altering IFT compared to monovalent ions (such as Na+ and Cl⁻), as they enhance asphaltene aggregation and interfacial film rigidity21,57,72. The addition of CTAB further modifies IFT by disrupting the interfacial network formed by natural surfactants and clay particles. Below, the main mechanisms are discussed in detail:

First, the presence of divalent ions (Mg2+, Ca2+, and SO42−) in smart water leads to the change in thickness of the electrical double layer (EDL) at the interface25. This process highlights how the expansion or compression of the EDL can be altered by the specific ions present in ion-modified water. Consequently, the EDL can create an environment that facilitates interactions between ions, surfactant molecules, clay particles, and the polar constituents of crude oil.

Second, divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) form complexes with polar components of crude oil, such as asphaltene molecules, at the oil-water interface. These complexes enhance the rigidity of the interfacial film, leading to a change in IFT values. The reactions lead to the formation of complexes are described by the following Eqs.6,73. The subscripts (o) and (aq) demonstrate the oil phase and aqueous phase, respectively.

As detailed in Eqs. 2–7, divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) in the brine solution react with carboxyl groups (-RCOOH) in asphaltenes through a complexation mechanism. This interaction results in surface-active complexes (-COOCa+ and -COOMg+) forming via ionic bonding, which subsequently adsorb at the oil-water interface74,75.

Third, the injection brine in heavy oil reservoir in the presence of clay initiates interactions between polar compounds in the oil and clay surfaces, driven by adhesion mechanisms such as cation bridging14,76. A significant aspect of this process is the role of silanol (Si-OH) groups on silica surfaces, which remain negatively charged across a wide spectrum of ionic strengths. This property enhances the tendency of asphaltene molecules to migrate toward the oil-water interface20,76. Therefore, cations can form a bridge between clay particles and a polar fraction of crude oil. The following equations represent the fundamental reactions in this cation-mediated bridging process:

As described in Eqs. (8)–(12), cation-clay interactions lead to the formation of bridging complexes (AlOCa+ and SiOCa+) at clay particle surfaces6. These modified clay surfaces can subsequently cause asphaltene’ interaction with clay particles at the interface6,20,76.

Another contributing mechanism involves the synergistic effect of CTAB and clay particles. In this process, CTA+ cations from CTAB interact electrostatically with SiO2 moieties on the clay surface, forming a monolayer of CTA+ cations around the clay particles, as indicated in Eq. 13. This leads to the formation of CTA+-clay hemi micelles77. As a result, the surface charge of the clay particles is neutralized, reducing their ability to adsorb oil components at the interface.

As can be seen in Fig. 3, the IFT of oil in SW2d is lower than in SW, and increasing the concentration of divalent cations (Mg2+ and Ca2+) in seawater elevates the IFT compared to the SW and SW2d samples. This trend can be attributed to the dilution of seawater, which increases the CTAB’s accumulation at the interface. According to the previous studies, reduced interfacial salinity promoted expansion of the electrical double layer9,50,75. This expansion led to the enhancement of the interfacial participation of CTAB molecules at the interface phenomena.

Moreover, clay particles could migrate more extensively at the oil-SW2d interface than at the oil-SW interface. According to equations of 8 to 12, the creation of cationic bridges via ions between clay and polar oil components (such as asphaltene molecules), combined with CTA+-clay interactions, could increase the involvement of polar oil components and surfactant of CTAB at the interface. The increased presence of CTAB molecules, as a highly active surfactant, alongside asphaltene molecules, led to a reduction in the IFT value.

As demonstrated in Fig. 3, the presence of divalent ions substantially increases IFT value due to reduced interfacial activity of CTAB molecules at the oil-water interface. Consistent with established literature, increasing divalent ion concentration enhanced competitive participation with CTAB molecules within the constrained EDL thickness23,28,57. This competition progressively diminished CTAB’s interfacial activity and consequently reduced its effectiveness in lowering IFT. Insufficient EDL thickness could lessen the formation of CTA+-clay micelles, which could also diminish the accumulation of clay and CTAB molecules at the interface.

Interestingly, the presence of active divalent cations increased the migration of polar oil components to the interface2,9. Asphaltenes moved to the interface via cationic bridging and complexation mechanisms76. Although these polar components contributed to a reduction in interfacial tension, the extent of this reduction is relatively modest. Consequently, the dominant mechanism at the oil-water interface shifted to the formation of asphaltene-ion complexes, which cannot considerably alter the IFT compared to SW and SW2d.

It is noteworthy that when interfacial tension was measured in calcium-enriched seawater (SW2d.4Ca), the IFT was observed approximately 18.8 mN/m lower than that of oil in (SW2d.4Mg) (IFT = 20.5 mN/m). The greater reduction in interfacial tension by calcium cations, compared to magnesium, was related to their lower charge density. This could facilitate the accumulation of CTAB molecules at the interface of oil-(SW2d.4Ca).

Moreover, reducing the concentration of magnesium ions from (SW2d.4Mg) to (SW2d.2Mg) caused the interfacial tension to approach that of SW2d. This shift can be related to the relative increase in the EDL thickness, enhanced involvement of CTAB molecules, and the formation of multiple oil-CTA+-clay and asphaltene-ion-clay complexes driven by the activation of the cation bridge mechanism76. A similar trend was observed for calcium ions, where (SW2d.4Ca) exhibited higher IFT (approximately 18.8 mN/m) than (SW2d.2Ca) (IFT = 15.4 mN/m), as can be seen in Fig. 3.

Conversely, when the sulfate-enriched seawater was used, the IFT value was observed at 5.3 mN/m (SW2d.2SO4) and 7.1 mN/m (SW2d.4SO4), respectively. This reduction was more pronounced for the (SW2d.2SO4) sample compared to (SW2d.4SO4). This phenomenon was related to the decreased concentration of divalent cations at the interface, which could enhance CTAB accumulation at the interface23,57. However, as the sulfate concentration increased, the EDL space could contract compared to the (SW2d.2SO4) sample, causing a lower number of CTAB molecules to participate at the interface and forming oil-CTA+-clay complexes.

Furthermore, electrostatic repulsion between negatively charged sulfate ions and the anionic polar components of crude oil (particularly asphaltenes) can significantly hinder their interfacial interactions. It can be concluded that the effectiveness of this mechanism can be reduced25,63. The negative charge of sulfate ions can also hinder the formation of asphaltene-ion-clay complexes. The repulsion between sulfate ions, the negatively charged clay, and the asphaltene molecules noticeably reduced cationic bridge interactions, particularly in the (SW2d.2SO4) solution. As a result, the dominant mechanisms in sulfate-enriched seawater were EDL expansion and the contribution of CTAB molecules, leading to a decrease in IFT value compared SW2d sample.

It is important to note that the clay surface can contribute to the formation of stable emulsions and alter interfacial properties6. However, the results from the IFT analysis did not provide sufficient insight into the influence of charged sites on clay and CTAB, nor their interactions in the aqueous phase. Therefore, zeta potential measurements could serve as a valuable tool to assess the effects of clay, CTAB, and ions on oil property changes, particularly through mechanisms involving clay particles.

Zeta (ζ) potential

Zeta potential is a critical parameter used to evaluate the surface charge and stability of colloidal particles, such as clay, in liquid suspensions78. It provides insights into the electrostatic interactions between particles and their surrounding medium, which are influenced by factors like pH, ionic strength, and the presence of surfactants or specific ions33,57. In this study, the zeta potential of clay particles was measured in solutions containing smart water and CTAB at the same time. By analyzing the zeta potential in these environments, we aim to understand how the surface charge of clay particles is affected by the unique chemical properties of smart water and the adsorption of CTAB molecules. Figure 4 depicts the zeta potential measurements of clay particles in brine and CTAB solutions.

As shown in Fig. 4, the zeta potential of clay particles in different aqueous phases enriched with divalent cations and anions ranged from 31.2 to 46.5 mV. Specifically, the zeta potential values for SW, SW2d, (SW2d.4Mg), (SW2d.4Ca), and (SW2d.4SO4) were observed at 40.4, 46.5, 34.8, 36.1, and 31.2 mV, respectively. This indicates that the highest zeta potential was achieved when the concentration of divalent ions in seawater remained unchanged and the overall seawater concentration was reduced. Additionally, the zeta potential for smart water enriched with (SW2d.2Mg), (SW2d.2Ca), and (SW.2SO4) followed the order: 38.9 mV (SW2d.2Ca) > 37.6 mV (SW2d.2Mg) > 32.7 mV (SW2d.2SO4). When the concentration of cations and divalent anions in the smart water was reduced, the zeta potential was greater compared to samples where their concentration was quadrupled relative to seawater.

As discussed in “Interfacial tension (IFT)”, diluting SW to the SW2d concentration caused a reduction in the concentration of active cations in the aqueous solution. The decrease in cation concentration can weaken the competitive interactions between cations and CTAB molecules in the enlarged EDL, leading to an increased affinity of CTAB for the negatively charged clay surface. It can be concluded that a significant proportion of CTAB molecules can remain adsorbed onto the clay surface, rather than being dispersed in the solution. This phenomenon explains the elevated zeta potential observed in the SW2d solution. Due to electrostatic interactions, CTAB can adsorb onto negatively charged surfaces, such as clay particles. This adsorption can increase the surface charge density of the particles, leading to increases in zeta potential79,80.

When the zeta potential of clay was measured in (SW2d.4Mg) and (SW2d.4Ca) solutions, the increased concentration of divalent cations in the aqueous solution intensified the competition between CTAB molecules and cations at the water-rock interface. Additionally, the EDL was significantly compressed in these solutions. As a result, CTAB molecules were unable to effectively adsorb onto the negatively charged clay surface, leading to a reduction in the zeta potential (magnitude), as represented in Fig. 4. It is important to note that the decrease in zeta potential was more pronounced in the (SW2d.4Mg) solution compared to the (SW2d.4Ca) solution. This difference could be attributed to the higher charge density and smaller ionic radius of magnesium ions compared to calcium ions81, which enables magnesium to more effectively occupy the space within the EDL, further limiting the adsorption of CTAB molecules25,82.

Figure 4 depicts that in (SW2d.2Mg) and (SW2d.2Ca) solutions, the ζ clay exhibited a more positive shift, with values of 37.6 mV and 38.9 mV, respectively. They approached the zeta potential value observed in the SW sample, compared to the values measured in (SW2d.4Mg) and (SW2d.4Ca) solutions. This shift can be attributed to the increased adsorption of CTAB molecules onto the clay surface under these conditions. As the Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions concentration decreases, the EDL can develop, and the competitive interactions between ions and CTAB molecules are reduced. In the (SW2d.2Ca) solution, competitive interactions are reduced relative to the (SW2d.2Mg) solution. This facilitated the formation of more extensive CTA+-clay hemi-micelles, resulting in a more positive zeta potential for clay in this system77.

In contrast to the zeta potential observed in solutions containing divalent cations, the zeta potential of clay in sulfate-enriched solutions exhibited a significant reduction compared to that in seawater, as can be seen in Fig. 4. This observation can be attributed to the reduced interaction between CTAB and clay surface83. More specifically, while the reduction of sulfate concentration can provide sufficient space for the expansion of the electrical double layer, the negatively charged sulfate ions likely compete with the clay surface for interaction with the positively charged CTAB cations84. This competition effectively limited the accumulation of CTAB onto the clay surface, thereby reducing the overall interaction between CTAB and the clay particles. This interaction limited the availability of CTAB molecules to adsorb onto the negatively charged clay surface85,86. It is worth mentioning that CTAB adsorption on clay particles would neutralize some of the negative charges, potentially increasing the net negative charge on the particles86,87. Since both the clay particles and sulfate ions carry a negative charge, there was minimal electrostatic interaction between them. This effect was more pronounced in the (SW2d.4SO4) (ζ = 31.2 mV) solution than in the (SW2d.2SO4) (ζ = 32.7 mV) solution, leading to a greater reduction in the zeta potential of clay in the (SW2d.4SO4) sample.

Emulsion analysis

The presence of CTAB, clay particles, and ions plays a critical role in modifying the properties of the liquid-liquid interface, particularly in emulsion systems. As highlighted in prior studies, the combined influence of ions and clay particles can lead to the formation of highly stable emulsions, which pose significant challenges in the petroleum industry78,88. It is well-established that the electrostatic fields generated by divalent ions or the surface charges of clay particles promote the aggregation and deposition of asphaltene molecules at the interface6. However, the introduction of CTAB can alter the stability of such emulsions89. To explore this effect, the stability of emulsions was systematically evaluated in this study. Emulsion stability was assessed by quantifying the percentage of separated water, oil, and solids in centrifuge tubes, as well as by analyzing the phase separation time of the emulsions. These results are illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6, providing a comprehensive view of the emulsion stability under varying conditions.

Figure 5 illustrates that the emulsions underwent phase separation within a range of 25 to 70 min. The emulsion formed with (SW2d.2SO4) exhibited the longest phase separation time (70 min), while the emulsion generated by (SW2d.4Mg) highlighted the shortest phase separation time (25 min) for oil-water and solid separation. Also, Fig. 6 depicts that the highest amount of solids and oil was separated from the emulsion formed with SW2d and (SW2d.2SO4), respectively. When seawater was enriched with divalent cations and sulfate, the weight% of solids and oil exhibited notable changes.

As discussed in Sects. “Interfacial tension (IFT)” and “Zeta (ζ) potential”, diluting seawater to the SW2d concentration expands the EDL, allowing CTAB molecules to participate more effectively in emulsion formation. This promotes significant migration of oil components to the interface compared to untreated seawater. Additionally, the presence of divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) in SW2d activates the cation bridging mechanism, as described in Eqs. 8–12. This mechanism is well-documented in the literature, where divalent cations form complexes with asphaltenes and clay particles, enhancing their interfacial activity6,20,76. It can be deduced that more asphaltene-ion and asphaltene-ion-clay complexes are formed within the expanded EDL of SW2d than SW sample. These mechanisms drive the migration of clay and asphaltene particles to the interface, resulting in a substantial increase in the solid percentage in the SW2d sample. The increased interactions of oil components at the interface, driven by these mechanisms, lead to a greater concentration of oil involved in interfacial phenomena compared to SW, (SW2d.4Ca), and (SW2d.4Mg). This creates electrostatic repulsion between the asphaltene-ion-clay, asphaltene-ion, and oil-CTA+-clay complexes on the surface. Thus, these interactions could result in the formation of more stable emulsions, consistent with previous research findings6,25,76,90.

Based on Fig. 5, the phase separation times for emulsions formed by SW, SW2d, (SW2d.4Ca), and (SW2d.4Mg) were 50 min, 55 min, 30 min, and 25 min, respectively. SW2d exhibited the longest separation time, demonstrating its ability to form a more stable emulsion owing to the higher presence of CTAB molecules in the emulsion phase.

In the emulsion formed with SW, however, the diminished thickness of the EDL restricted the presence of CTAB molecules relative to SW2d, reducing electrostatic repulsion at the interface. As a result, the emulsion stability in SW was lower than in SW2d, aligning with the results shown in Fig. 5. As elaborated in the zeta potential section, the heightened competition between cations and CTAB molecules in SW hindered CTAB’s interaction with the clay surface. This limited the involvement of clay particles in the emulsion phase, resulting in a lower solid content, as evidenced in Fig. 6.

In the emulsion-(SW2d.4Mg) and emulsion-(SW2d.4Ca), as depicted in Fig. 6, the oil percentages are approximately 32.43% and 33.69%, while the solid percentages are around 7.68% and 7.54%, respectively. This was attributed to the charge density of cations. Regarding the higher charge density of magnesium compared to calcium, a greater concentration of magnesium ions can be incorporated into the emulsion phase. This enhanced the affinity of polar oil components for the interface through the complexation mechanism and clay particles through the cation bridge interaction, resulting in a higher separation of solids in the (SW2d.4Mg) system25. However, CTAB molecules negligibly participated in the emulsion phase formed by (SW2d.4Mg) compared to (SW2d.4Ca), as Mg2+ molecules exhibit stronger competition than Ca2+ molecules for interfacial sites, as discussed in Sect. 3.1 and 3.2. The increased CTAB concentration enhanced the migration of oil components toward the calcium-rich seawater interface. This interfacial accumulation of oil, combined with calcium’s bridging and complexing effects, promoted the formation of more stable emulsions. This is consistent with established literature demonstrating that higher oil content in the emulsion phase correlates with enhanced emulsion stability56. On the other hand, the emulsion-(SW2d.4Mg) represented the lowest stability among the tested formulations, as evidenced by its rapid phase separation time of 25 min (Fig. 5).

Additionally, reducing the concentration of calcium and magnesium cations in the smart water resulted in a higher amount of separated oil compared to the (SW2d.4Mg) and (SW2d.4Ca) samples. This can be attributed to the expansion of the EDL caused by the decrease in salinity. Lower salinity could result in the presence of CTAB molecules at the interface and, in turn, promote stronger interactions with the oil phase components considerably23,28,57. This effect was more pronounced for calcium owing to its lower charge density compared to magnesium. Moreover, clay particles contribute to interfacial interactions, facilitating the formation of more asphaltene-ion-clay complexes. Hence, the emulsion formed with (SW2d.2Ca) exhibited greater stability than that formed with (SW2d.2Mg).

In contrast to seawater enriched with magnesium and calcium, sulfate-rich seawater formed the most stable emulsion. This stability was further exacerbated when the sulfate concentration weakened from (SW2d.4SO4) to (SW2d.2SO4). The higher sulfate concentration significantly compressed the EDL, reducing the presence of CTAB molecules at the interface.

More interestingly, sulfate ions, asphaltenes, and clay particles all carry negative charges, the cationic bridging mechanism was considerably less effective in (SW2d.4SO4) compared to (SW2d.2SO4). Nevertheless, the interaction between CTAB with clay particles can form oil-CTA+-clay complexes. These interactions were more pronounced in the emulsion formed with (SW2d.4SO4), causing the enhanced accumulation of oil components at the interface. It can be concluded that the percentage of solids and oil separated from the (SW2d.2SO4) emulsion was higher than that from (SW2d.4SO4), the electrostatic repulsion between the droplets prevented coalescence, and a more stable emulsion was generated9,75,91. The emulsion separation time corroborates these findings, which are also in agreement with the IFT and zeta potential results.

It is worth mentioning that the emulsification of trapped oil following smart water flooding plays a crucial role in enhancing oil recovery by lowering the IFT value and mobilizing trapped oil92,93. The results indicate that (SW2d.2SO4) generates a highly stable emulsion with reduced solid content compared to other samples, making it effective for improving residual oil recovery.

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR)

Various polar components of crude oil, including asphaltenes, can migrate toward the interface, influencing emulsion behavior. In addition, non-polar compounds may interact with CTAB molecules at the interface, leading to changes in their concentration within the oil phase. Distinguishing these functional groups is crucial for understanding the interfacial mechanisms governing emulsion formation during smart water flooding, particularly in the presence of clay particles and CTAB molecules. The FTIR spectroscopy technique precisely identifies polar and non-polar functional groups61,94. In this study, FTIR spectroscopy was employed to analyze crude and aged oil samples. The results are shown in Fig. 7.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, the FTIR transmission spectra of crude and aged oils were compared. The FTIR spectra revealed five main peaks, which are the same in all samples and their transmission just changed, and no new peak appeared or was removed. Peaks 1 and 2, observed at 2725–2735 cm− 1 and 2950–2970 cm− 1, were attributed to HC = O (carboxylic acid) and C-H axial stretching, respectively60,95. Peak 3, located at 1450–1480 cm− 1, relates to the stretching vibrations of CH3 groups. Peak 4, at 1350–1380 cm− 1, was associated with the asymmetric stretching of methyl groups. Peak 5, appearing at approximately 710–870 cm− 1, is indicative of aromatic ring vibration, the peak at 3060 cm− 1 is characteristic of aromatic C-H stretching22,60.

A detailed analysis of the results revealed that the peaks at 3000–3100 cm− 1 and 1580–1630 cm− 1 correspond to C-H stretching and C = C stretching in aromatic ring structures, respectively6. The peaks observed at 2935 ± 5 cm− 1 and 2965 ± 5 cm− 1 correspond to the symmetric stretching of CH3 bonds and the asymmetric stretching of CH3 bonds, respectively, both characteristic of alkane groups60. The presence of these peaks confirms the existence of aliphatic chains in the crude oil. Figure 7 illustrates the FTIR spectra of all oil samples within the 2800–2970 cm− 1 range, showing these peaks with relatively low intensity. The characteristic peaks, along with their associated functional groups and potential bonds, are summarized in Table 4.

The findings reported in Fig. 7 can be accurately assessed using the indices outlined in Sect. 2.7. These quantitative indices are essential for facilitating comparisons of FTIR spectra across different aged oil samples and crude oil. Various indices, as described in Eq. 14 through 17, correspond to a range of functional groups and can be utilized for this analytical process6,22,60. “A” corresponds to the peak area of the bonds in the FTIR spectra.

According to Table 5, the change in the LC index was relatively constant in oil contacted with seawater enriched with divalent ions. However, the LC index values for aged oil-SW2d, aged oil-(SW2d.2SO4), and aged oil-(SW2d.4SO4) were 0.284, 0.233, and 0.260, respectively, showing significant variations compared to other oils. As defined by Eq. 14 and Table 5, this index reflects the presence of non-polar components in the oil. Thus, its decrease suggests a reduction in non-polar components in the aged oils. Regarding the results acquired in “Emulsion analysis”, the higher concentration of CTAB molecules in sulfate-containing emulsions facilitated the participation of non-polar oil components and CTAB in interfacial reactions, as observed in these samples. Consistent with previous research23,57,96, an increase in CTAB molecules enhances the affinity of non-polar components for accumulation at the interface, as evidenced in the emulsion formed with (SW2d.2SO4). This phenomenon also lead to a reduction in the adsorption of polar asphaltenes molecules on the clay surfaces97.

The PA index represents polar aromatic groups, and the ARO index corresponds to aromatic rings in components of the oil phase, such as asphaltene molecules60. These molecular characteristics - polarity and aromaticity - collectively govern asphaltene stability, with their relative proportions determining aggregation propensity in emulsion phase98. Therefore, a reduction in peak area indicates a lower concentration of polar and unstable poly-aromatic compounds, including asphaltene, in the aged oil bulk.

The ARO index, measured at 0.565 in crude oil, declined to between 0.308 and 0.410 in aged oils exposed to cation-rich seawaters. Table 5. represents that the PA and ARO indices were lower for aged oil-(SW2d.2Mg), aged oil-(SW2d.2Ca), aged oil-(SW2d.4Mg), and aged oil-(SW2d.4Ca) compared to sulfate-rich seawater and aged oil-SW2d samples. The largest decrease in the ARO and PA indices occurred in aged oil-(SW2d.4Mg), driven by the activation of cationic bridging and asphaltene-ion complexes mechanisms. This indicates that highly polar asphaltene molecules migrated to the emulsion phase, reducing their concentration in the oil phase.

It is important to note that the concentration of polar components in aged oil-SW2d (PA = 0.585, aged oil-(SW2d.2SO4) (PA = 0.682), and aged oil-(SW2d.4SO4) (PA = 0.627) also showed a slight decline, as reported in Table 5. This was related to the inability of polar and heavy components of oil, such as asphaltene molecules, which carry negative charges, to interact with clays or sulfates at the fluid-fluid interface, causing them to remain in the oil phase. Meanwhile, non-polar components were more likely to react with the non-polar chains of CTAB at the interface, as indicated by the LC index.

The ALI is associated with aliphatic compounds in oil, and alteration in this index indicates a reduction in aliphatic components. Significantly aliphatic groups are attributed to alkane chains, with their carbon numbers determined by the long-chain index. Nonetheless, sulfoxides, which are highly polar sulfur compounds found in crude oil, are attached to aliphatic branches, polarizing certain aliphatic groups, including those in asphaltene60. Therefore, a decrease in both the AS=O and ALI indices can be attributed to the adsorption of asphaltene molecules with higher aliphatic groups at the interface, which are mainly polarized by the S = O stretch.

The ALI index and AS=O values for aged oils range from 0.196 to 0.332 and 0.483 to 0.670, respectively. For oils contacted with seawater enriched with 4Mg, 4Ca, and 4SO4, the ALI index and S = O stretching peak area decrease as follows: aged oil-(SW2d.4SO4) (ALI = 0.309, AS=O = 0.656) > aged oil-(SW2d.4Ca) (ALI = 0.222, AS=O = 0.514) > aged oil-(SW2d.4Mg) (ALI = 0.186, AS=O = 0.483), as given in Table 5. A similar trend was observed when the concentrations of Mg2+, Ca2+, and SO42− were reduced. These changes are primarily as a consequence of the migration of polar and heavy asphaltene compounds from the oil phase toward the interface, while non-polar components remained in the oil bulk. This phenomenon was more pronounced in seawater enriched with magnesium, owing to complexation and cationic bridging mechanisms.

Based on the results from Sect. 3.3, among all ion-enriched solutions, magnesium-enriched water produced the highest solid content, indicating significant clay participation in interfacial phenomena. Additionally, as shown in Sect. 3.1, the highest interfacial tension was observed in (SW2d.4Mg), demonstarting a reduced presence of CTAB molecules in the emulsion phase. Hence, magnesium enhanced the contribution of clay and asphaltene at the interface through cationic bridging and complexation mechanisms, increasing the affinity of sulfoxide-polarized asphaltene molecules for the interface while leaving less-polar components in the oil bulk. These findings are consistent with the calculated PA, ARO, and LC indices.

Contact angle

The contact angle of the rock was measured in various solutions to better understand the synergistic effect of ion-tuned water and CTAB molecules on the rock surface and their impact on wettability alteration. Each experiment was repeated three times to ensure reproducibility. Figure 8 presents time-lapse images documenting the wettability alteration process, and Fig. 9 displays the corresponding averaged quantitative results.

As shown in Fig. 9, the changes in contact angle for seawater enriched with active cations followed this order: (SW2d.4Mg) > (SW2d.4Ca) > (SW2d.2Mg) > (SW2d.2Ca). Moreover, when sulfate was used and seawater was diluted (SW2d), the contact angles reached 31°, 34°, and 35.5° for (SW2d.2SO4), (SW2d.4SO4), and SW2d, respectively.

As discussed in the previous sections, when the sulfate concentration in seawater was altered, CTAB molecules exhibited a greater tendency to accumulate at the interface. These molecules could approach the rock surface, detaching adherent oil and dissolving it in the aqueous phase57,99. This phenomenon became more pronounced when the sulfate concentration was reduced to (SW2d.2SO4), as the participation of CTAB molecules increases. The results of the LC index indicate the most significant decrease in less polar components of the aged oil in the (SW2d.2SO4) solution, confirming enhanced interactions between CTAB molecules and oil at the interface32. This demonstrates the optimal performance of CTAB in wettability alteration.

According to the PA, ARO, and ALI indices, polar asphaltenes have a stronger tendency to accumulate at the interface, where they interact with magnesium and calcium cations through complexation mechanisms. This cause substantial competition for CTAB molecules at the interface, reducing their ability to adsorb and transport oil to the aqueous phase and diminishing their impact on wettability alteration. Figure 9 demonstrates that the contact angle for (SW2d.4Mg) is the highest. Magnesium’s higher charge density allowed its components to occupy more interfacial space, significantly restricting the aggregation of CTAB molecules.

Another point to be noted is that SW and SW2d were more effective in reducing the contact angle than magnesium- and calcium-enriched seawaters. In the SW solution, the sulfate concentration was higher than in (SW2d.4Mg) and (SW2d.4Ca), which enhanced the migration of CTAB molecules to the interface. On the other hand, diluting seawater to SW2d reduced the contact angle, attributed to the lower cation concentration and the increased space available for CTAB molecules at the interface. These findings are consistent with the results obtained in previous sections.

Conclusions

The goal of this experimental research was to examine the combined effects of ion-tuned water, CTAB, and clay on emulsions and oil behavior. Increasing emulsion stability can facilitate the recovery of trapped oil and enhance overall oil recovery. A variety of experimental tests were performed to analyze oil behavior in the presence of synergistic interactions among brine, CTAB, and clay particles. Furthermore, the emulsion and aged oil were studied to understand the synergistic impact of ion-tuned water, CTAB, and clay on the emulsion phase. The experimental results led to the following conclusions:

-

1.

According to the IFT test results, it was observed that regardless of active ion concentration in the smart water phases, seawater containing divalent sulfate anions considerably reduced IFT, while smart water created by divalent magnesium and calcium cations increased interfacial tension. This behavior is attributed to the reduced presence of CTAB molecules at the oil-water interface in magnesium- and calcium-enriched solutions and the increased presence of CTAB molecules at the oil-water interface in sulfate-enriched solutions.

-

2.

In sulfate-tuned waters, the zeta potential of clay particles was less positive than in other aqueous phases as a consequence of the decrease in the concentration of cations in the aqueous phase. Conversely, in cation-rich seawater, SW, and SW2d solutions, the competition between CTAB and cations for interaction with the clay surface led to a more positive zeta potential, especially in the SW2d solution.

-

3.

The stability of the emulsions increased when sulfate-rich seawater was used, as evidenced by the emulsion separation time and the mass of oil in the emulsion phase. Due to the reduction in asphaltene-ion and asphaltene-ion-clay complexes in sulfate-containing emulsions, the amount of solids was significantly lower compared to other emulsions.

-

4.

As indicated by the FTIR indices, polar asphaltenes demonstrate stronger interactions with cations, whereas non-polar components interact with CTAB molecules in the emulsion phase. The inclusion of sulfate ions in brine solutions intensifies the interaction between CTAB and non-polar oil compounds, especially (SW2d.2SO4).

-

5.

The (SW2d.2SO4) solution exhibited the lowest contact angle, reflecting a higher concentration of CTAB molecules at the fluid-rock interface and substantial improvements in wettability alteration.

-

6.

The synergistic interaction of CTAB molecules, clay particles, and sulfate-enriched seawater achieved maximum emulsion stability and minimal solids in the emulsion phase, the IFT, and contact angle. These outcomes are crucial for enhancing trapped oil recovery and provide substantial advantages to the oil industry.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

References

Al-Shalabi, E. W. & Sepehrnoori, K. A comprehensive review of low salinity/engineered water injections and their applications in sandstone and carbonate rocks. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 139, 137–161 (2016).

Salehi, N., Dehaghani, A. S. & Haghighi, M. Investigation of fluid-fluid interaction between surfactant-ion-tuned water and crude oil: A new insight into asphaltene behavior in the emulsion interface. J. Mol. Liq. 376, 121311 (2023).

Fang, T. et al. Multi-scale mechanics of submerged particle impact drilling. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 285, 109838 (2025).

Agyei, A. I. Evaluation of Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) Efficiency of Smart Water, Ionic Liquid Blends Using Spontaneous Imbibition Tests (UIS, 2024).

Maghsoudian, A. et al. Utilizing deterministic smart tools to predict recovery factor performance of smart water injection in carbonate reservoirs. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 537 (2025).

Mahdavi, M. S. et al. The synergic effect of Brine salinity and dispersed clay particles on Water-in-Heavy oil emulsion: insight into asphaltene structure and emulsion stability. SPE J. 1–17. (2024).

Austad, T., RezaeiDoust, A. & Puntervold, T. Chemical mechanism of low salinity water flooding in sandstone reservoirs. In SPE improved oil recovery symposium. OnePetro. (2010).

Gbadamosi, A. et al. Recent advances on the application of low salinity waterflooding and chemical enhanced oil recovery. Energy Rep. 8, 9969–9996 (2022).

Balavi, A., Ayatollahi, S. & Mahani, H. The Simultaneous Effect of Brine Salinity and Dispersed Carbonate Particles on Asphaltene and Emulsion Stability37p. 5827–5840 (Energy & Fuels, 2023). 8.

Zolfaghari, R. et al. Demulsification techniques of water-in-oil and oil-in-water emulsions in petroleum industry. Sep. Purif. Technol. 170, 377–407 (2016).

Sousa, A. M., Matos, H. A. & Pereira, M. J. Properties of crude oil-in-water and water-in-crude oil emulsions: a critical review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 61 (1), 1–20 (2021).

Pei, H. et al. Potential of alkaline flooding to enhance heavy oil recovery through water-in-oil emulsification. Fuel 104, 284–293 (2013).

Ellingsen, H., Jaouhar, H. & Hannisdal, A. Elimination of Tight Emulsions. In Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference. SPE. (2021).

Joonaki, E. et al. Water versus asphaltenes; liquid–liquid and solid–liquid molecular interactions unravel the mechanisms behind an improved oil recovery methodology. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 11369 (2019).

Makeen, Y. M. et al. Reservoir quality and its controlling diagenetic factors in the Bentiu formation, Northeastern Muglad basin, Sudan. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 18442 (2021).

Yue, L. et al. Insights into mechanism of low salinity water flooding in sandstone reservoir from interfacial features of oil/brine/rock via intermolecular forces. J. Mol. Liq. 313, 113435 (2020).

Matocha, C. J. Clay: Charge Properties (Encyclopedia of Soil Science, Taylor & Francis, 2006).

Ng, A. et al. Asphaltenes Contribution In Emulsion Formation during Solvent-Steam Processes. In SPE Western Regional Meeting (SPE, 2018).

Liu, J. et al. Study on the kinetics of formation process of emulsion of heavy oil and its functional group components. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 8916 (2024).

Demir, A. B., Bilgesu, H. I. & Hascakir, B. The Effect of Clay and Salinity on Asphaltene Stability. In SPE Western Regional Meeting (SPE, 2016).

Lashkarbolooki, M. et al. Synergy effects of ions, resin, and asphaltene on interfacial tension of acidic crude oil and low–high salinity Brines. Fuel 165, 75–85 (2016).

Tajikmansori, A. et al. New insights into effect of the electrostatic properties on the interfacial behavior of asphaltene and resin: an experimental study of molecular structure. J. Mol. Liq. 377, 121526 (2023).

Tajikmansori, A., Dehaghani, A. H. S. & Haghighi, M. Improving chemical composition of smart water by investigating performance of active cations for injection in carbonate reservoirs: A mechanistic study. J. Mol. Liq. 348, 118043 (2022).

Liang, C. et al. Dissipative particle Dynamics-Based simulation of the effect of asphaltene structure on Oil–Water interface properties. ACS Omega. 8 (36), 33083–33097 (2023).

Mahdavi, M. S. & Dehaghani, A. H. S. Experimental study on the simultaneous effect of smart water and clay particles on the stability of asphaltene molecule and emulsion phase. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 3393 (2025).

Demir, A. B., Bilgesu, H. I. & Hascakir, B. Interaction of n-pentane and n-heptane insoluble asphaltenes in Brine with clay and sand. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 209, 109870 (2022).

Aghdam, S. K., Kazemi & Ahmadi, M. Studying the effect of various surfactants on the possibility and intensity of fine migration during low-salinity water flooding in clay-rich sandstones. Results Eng. 18, 101149 (2023).

Dehaghani, A. H. S. et al. A mechanistic investigation of the effect of ion-tuned water injection in the presence of cationic surfactant in carbonate rocks: an experimental study. J. Mol. Liq. 304, 112781 (2020).

Seng, L. Y., Al-Shaikh, M. & Hascakir, B. Intermolecular interaction between heavy crude oils and surfactants during surfactant-steam flooding process. ACS Omega. 5 (42), 27383–27392 (2020).

Hou, B. et al. Mechanism of synergistically changing wettability of an oil-wet sandstone surface by a novel nanoactive fluid. Energy Fuels. 34 (6), 6871–6878 (2020).

Maurya, N. K. & Mandal, A. Investigation of synergistic effect of nanoparticle and surfactant in macro emulsion based EOR application in oil reservoirs. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 132, 370–384 (2018).

Aghdam, S. K., Kazemi & Ahmadi, M. Studying the effect of surfactant assisted low-salinity water flooding on clay-rich sandstones. Petroleum 10 (2), 306–318 (2024).

Taheri-Shakib, J. et al. A comprehensive study of asphaltene fractionation based on adsorption onto calcite, dolomite and sandstone. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 171, 863–878 (2018).

Jia, H. et al. Mechanism studies on the application of the mixed cationic/anionic surfactant systems to enhance oil recovery. Fuel 258, 116156 (2019).

Kamal, M. S., Hussein, I. A. & Sultan, A. S. Review on surfactant flooding: phase behavior, retention, IFT, and field applications. Energy Fuels. 31 (8), 7701–7720 (2017).

Nourani, M. et al. Desorption of crude oil components from silica and aluminosilicate surfaces upon exposure to aqueous low salinity and surfactant solutions. Fuel 180, 1–8 (2016).

Koreh, P. et al. Interfacial performance of cationic, anionic and non-ionic surfactants; effect of different characteristics of crude oil. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 218, 110960 (2022).

Javadi, A. H. & Fatemi, M. Impact of salinity on fluid/fluid and rock/fluid interactions in enhanced oil recovery by hybrid low salinity water and surfactant flooding from fractured porous media. Fuel 329, 125426 (2022).

Zallaghi, M. & Khaz’ali, A. R. Experimental and modeling study of enhanced oil recovery from carbonate reservoirs with smart water and surfactant injection. Fuel 304, 121516 (2021).

Liu, Q. et al. Improved oil recovery by adsorption–desorption in chemical flooding. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 43 (1–2), 75–86 (2004).

Hou, B. et al. Mechanisms of spontaneous imbibition and wettability reversal of sandstone cores by a novel imbibition agent. Energy Fuels. 36 (3), 1316–1325 (2022).

Hou, B. et al. A novel high temperature tolerant and high salinity resistant gemini surfactant for enhanced oil recovery. J. Mol. Liq. 296, 112114 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Understanding the cation-dependent surfactant adsorption on clay minerals in oil recovery. Energy Fuels. 33 (12), 12319–12329 (2019).

Mostafa, E. M. et al. In-situ upgrading of Egyptian heavy crude oil using matrix polymer carboxyl Methyl cellulose/silicate graphene oxide nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 20985 (2024).

Soliman, A. A. et al. Optimizing in-situ upgrading of heavy crude oil via catalytic aquathermolysis using a novel graphene oxide-copper zinc ferrite nanocomposite as a catalyst. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 25845 (2024).

Li, N. et al. Unified nonlinear elasto-visco‐plastic rheology for bituminous rocks at variable pressure and temperature. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth, 130(3). e2024JB029295 (2025).

Leon, O. et al. Asphaltenes: structural characterization, self-association, and stability behavior. Energy Fuels. 14 (1), 6–10 (2000).

Alotaibi, M. B., Nasr-El-Din, H. A. & Fletcher, J. J. Electrokinetics of limestone and dolomite rock particles. SPE Reservoir Eval. Eng. 14 (05), 594–603 (2011).

Fathi, S. J., Austad, T. & Strand, S. Smart water as a wettability modifier in chalk: the effect of salinity and ionic composition. Energy Fuels. 24 (4), 2514–2519 (2010).

Mehraban, M. F. et al. Fluid-fluid interactions inducing additional oil recovery during low salinity water injection in inefficacious presence of clay minerals. Fuel 308, 121922 (2022).

Gan, B. et al. Phase transitions of CH4 hydrates in mud-bearing sediments with oceanic laminar distribution: mechanical response and stabilization-type evolution. Fuel 380, 133185 (2025).

Vasconcelos, I. F., Bunker, B. A. & Cygan, R. T. Molecular dynamics modeling of ion adsorption to the basal surfaces of kaolinite. J. Phys. Chem. C. 111 (18), 6753–6762 (2007).

Raya, S. A. B. Analysis of Synergistic Effect of Silica Nanoparticles and Surfactants on Oil-In-Water Emulsion Resolution. (2022).

Mahmoudi Alemi, F. & Mohammadi, S. Experimental Study on Water-in-Oil Emulsion Stability Induced by Asphaltene Colloids in Heavy Oil (ACS omega, 2025).

Kumar, S. & Mahto, V. Emulsification of Indian heavy crude oil in water for its efficient transportation through offshore pipelines. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 115, 34–43 (2016).

Yang, F. et al. Pickering emulsions stabilized solely by layered double hydroxides particles: the effect of salt on emulsion formation and stability. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 302 (1), 159–169 (2006).

Tajikmansori, A., Hosseini, M. & Dehaghani, A. H. S. Mechanistic study to investigate the injection of surfactant assisted smart water in carbonate rocks for enhanced oil recovery: an experimental approach. J. Mol. Liq. 325, 114648 (2021).

Noorizadeh Bajgirani, S. S., Saeedi, A. H. & Dehaghani Experimental investigation of wettability alteration, IFT reduction, and injection schemes during surfactant/smart water flooding for EOR application. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 11362 (2023).

Gupta, V. et al. Particle interactions in kaolinite suspensions and corresponding aggregate structures. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 359 (1), 95–103 (2011).

Zojaji, I., Esfandiarian, A. & Taheri-Shakib, J. Toward molecular characterization of asphaltene from different origins under different conditions by means of FT-IR spectroscopy. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 289, 102314 (2021).

Karami, S., Dehaghani, A. S. & Haghighi, M. Analytical investigation of asphaltene cracking due to microwave and ultrasonic radiations: A molecular insight into asphaltene characterization and rheology. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 233, 212481 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Axial compressive behavior of circular hollow steel tube-reinforced UHTCC column. in Structures. Elsevier. (2025).

Kazemi, A., Khezerloo-ye, S., Aghdam & Ahmadi, M. Theoretical and experimental investigation of the impact of oil functional groups on the performance of smart water in clay-rich sandstones. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 20172 (2024).

Zhang, P., Tweheyo, M. T. & Austad, T. Wettability alteration and improved oil recovery by spontaneous imbibition of seawater into chalk: impact of the potential determining ions Ca2+, Mg2+, and SO42–. Colloids Surf., A. 301 (1–3), 199–208 (2007).

Su, Y. et al. Soil-water retention behaviour of fine/coarse soil mixture with varying coarse grain contents and fine soil dry densities. Can. Geotech. J. 59 (2), 291–299 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Axial compression mechanical properties of UHTCC–hollow steel tube square composited short columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 228, 109424 (2025).

Ren, Q. X., Zhou, K. & Li, W. Experimental study of clay concrete filled steel tubular stub columns under axial compression. in Structures. Elsevier. (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Study of bond-slip push-out test of circular Hollow steel tube and UHTCC. J. Constr. Steel Res. 223, 109043 (2024).

Mansouri Zadeh, M. et al. Synthesis of colloidal silica nanofluid and assessment of its impact on interfacial tension (IFT) and wettability for enhanced oil recovery (EOR). Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 325 (2024).

Yin, B. et al. An experimental and numerical study of gas-liquid two-phase flow moving upward vertically in larger annulus. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 19 (1), 2476605 (2025).

Ramezani, M., Lashkarbolooki, M. & Abedini, R. Experimental investigation of different characteristics of crude oil on the interfacial activity of anionic, cationic and nonionic surfactants mixtures. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 214, 110485 (2022).

Lashkarbolooki, M. et al. Low salinity injection into asphaltenic-carbonate oil reservoir, mechanistical study. J. Mol. Liq. 216, 377–386 (2016).

Mokhtari, R., Ayatollahi, S. & Fatemi, M. Experimental investigation of the influence of fluid-fluid interactions on oil recovery during low salinity water flooding. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 182, 106194 (2019).

Mokhtari, R. et al. Asphaltene destabilization in the presence of an aqueous phase: the effects of salinity, ion type, and contact time. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109757 (2022).

Taherian, Z. et al. The mechanistic investigation on the effect of the crude oil/brine interaction on the interface properties: A study on asphaltene structure. J. Mol. Liq. 360, 119495 (2022).

da Costa, A. A. et al. An experimental evaluation of low salinity water mechanisms in a typical Brazilian sandstone and light crude oil with low acid/basic number. Fuel 273, 117694 (2020).

Fouconnier, B., Román-Guerrero, A. & Vernon-Carter, E. J. Effect of [CTAB]–[SiO2] ratio on the formation and stability of hexadecane/water emulsions in the presence of NaCl. Colloids Surf., A. 400, 10–17 (2012).

Yekeen, N. et al. Synergistic influence of nanoparticles and surfactants on interfacial tension reduction, wettability alteration and stabilization of oil-in-water emulsion. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 186, 106779 (2020).

Rosen, M. Surfactants and Interfacial Phenomena, 3rd Edn. NewYork: JohnWiley and Sons (Inc, 2004).

Atkin, R. et al. Mechanism of cationic surfactant adsorption at the solid–aqueous interface. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 103 (3), 219–304 (2003).

Alroudhan, A., Vinogradov, J. & Jackson, M. Zeta potential of intact natural limestone: impact of potential-determining ions ca, Mg and SO4. Colloids Surf., A. 493, 83–98 (2016).

Bonto, M., Eftekhari, A. A. & Nick, H. M. An overview of the oil-brine interfacial behavior and a new surface complexation model. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 6072 (2019).

Li, T. et al. Capillary of engineered cementitious composites using steel slag aggregate. J. Building Eng. 98, 111504 (2024).

Zhang, R. & Somasundaran, P. Advances in adsorption of surfactants and their mixtures at solid/solution interfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 123, 213–229 (2006).

Bergaya, F. & Lagaly, G. Handbook of Clay ScienceVol. 5 (Newnes, 2013).

Gürses, A. et al. Monomer and micellar adsorptions of CTAB onto the clay/water interface. Desalination 264 (1–2), 165–172 (2010).

Moslemizadeh, A. et al. Assessment of swelling inhibitive effect of CTAB adsorption on montmorillonite in aqueous phase. Appl. Clay Sci. 127, 111–122 (2016).

Kazemzadeh, Y. et al. Experimental investigation of stability of water in oil emulsions at reservoir conditions: effect of ion type, ion concentration, and system pressure. Fuel 243, 15–27 (2019).

Xin, X. et al. Influence of CTAB and SDS on the properties of oil-in-water nano-emulsion with paraffin and span 20/tween 20. Colloids Surf., A. 418, 60–67 (2013).

Sztukowski, D. M. & Yarranton, H. W. Oilfield solids and water-in-oil emulsion stability. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 285 (2), 821–833 (2005).

Abbasi, A., Malayeri, M. R. & Shirazi, M. M. Stability of spent HCl acid-crude oil emulsion. J. Mol. Liq. 383, 122116 (2023).

Chakraborty, R. et al. Synergistic Effects of Nonionic Surfactant and Organic Alkali for Enhanced Oil Recovery: Optimizing Interfacial Tension Reduction, Emulsion Stability, and Corrosion Control Under Optimal Salinity Conditions (Energy & Fuels, 2025).

Deng, R., Dong, J. & Dang, L. Numerical simulation and evaluation of residual oil saturation in waterflooded reservoirs. Fuel 384, 134018 (2025).

Karami, S., Dehaghani, A. H. S. & Mousavi, S. A. H. S. Condensate blockage removal using microwave and ultrasonic waves: discussion on rock mechanical and electrical properties. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 193, 107309 (2020).

Karami, S. & Dehaghani, A. H. S. A molecular insight into cracking of the asphaltene hydrocarbons by using microwave radiation in the presence of the nanoparticles acting as catalyst. J. Mol. Liq. 364, 120026 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Effect of dispersants on the stability of calcite in non-polar solutions. Colloids Surf., A. 672, 131730 (2023).

Hou, B. et al. Mechanism of wettability alteration of an oil-wet sandstone surface by a novel cationic gemini surfactant. Energy Fuels. 33 (5), 4062–4069 (2019).

Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. et al. Toward mechanistic Understanding of asphaltene aggregation behavior in toluene: the roles of asphaltene structure, aging time, temperature, and ultrasonic radiation. J. Mol. Liq. 264, 410–424 (2018).

Maiki, E. P. et al. Experimental and molecular dynamics simulation to investigate oil adsorption and detachment from sandstone/quartz surface by Low-Salinity surfactant Brines. ACS Omega. 9 (18), 20277–20292 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.M: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Review& editing, Writing. A.T.M: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Formal analysis, Resources, Review& editing, Writing. A.H.S.D: Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Review& editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahdavi, M.S., Mansouri, A.T. & Dehaghani, A.H.S. Experimental investigation of CTAB modified clay on oil recovery and emulsion behavior in low salinity water flooding. Sci Rep 15, 21471 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07591-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07591-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Experimental investigation of divalent ions and CTAB effects on heavy oil emulsion stability in carbonate reservoirs

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Synergistic effects of CTAB and low salinity brines on asphaltene behavior and emulsion stability in clay rich sandstone reservoirs

Scientific Reports (2025)