Abstract

Boxwood, a low-maintenance landscape plant, has been plagued by diseases in recent years, and fungicide protection is now indispensable for its healthcare. The objective of present study was to determine how fungicide chemistry and repeated application may affect phyllosphere mycobiome. Three fungicides—Daconil (chlorothalonil, contact chemistry), Banner Maxx (propiconazole, systemic chemistry), and Concert II (a combination of both chemistries)—were first applied on April 12 then repeated at 2- and 3-week intervals, product dependent. Shoots from Buxus sempervirens ‘Vardar Valley’ were sampled immediately before, 1, 7 and 14 days after fungicide application on May 26 and August 25. As determined by amplicon sequencing, fungal community composition differed between shoot surface and internal tissue, with the former being dominated by Cladosporium and the latter by Shiraia species. Fungicide applications strongly affected epiphytic fungal community diversity, structure, and many functional groups. Daconil and Concert II suppressed greater numbers of epiphytes than Banner Maxx. Many epiphytic genera became less sensitive to Daconil treatment in August. This study provided the first mycobiome evidence supporting boxwood as a low-maintenance plant and demonstrating fungicide resistance to a multisite chemistry due to repeated applications. It also helped understand boxwood rising health issues associated with increasing fungicide use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fungi, one of the largest members in plant phyllosphere microbial communities1 are integral to plant growth and health2. They may reside on plant surfaces as epiphytes or in tissues as endophytes3. Some epiphytes and endophytes confer beneficial traits such as promoting plant growth4 and enhancing plant resistance to diseases5 herbivores6 and environmental stressors7 while others are plant pathogens. It is the balance of these coexisting fungi that sustains both plant fitness and health8. This intricate balance, however, may be interrupted by some crop management practices such as use of agrochemicals in modern agriculture9,10,11, leading to the decline of plant fitness and making plants more vulnerable to diseases8,12.

Among the most impactful agrochemicals are fungicides, which are commonly used to protect crops from infection by different fungal pathogens in agriculture and horticulture. Depending on their mobility, fungicides can be broadly classified as contact or systemic. Contact fungicides act primarily on plant surface while systemic fungicides can penetrate through the plant’s cuticle barriers to act against pathogens inside the plant tissues41. Depending on their modes of action, fungicides are formulated to interfere with one or more physiological processes (single-site vs. multiple-site) of the target pathogens, therefore achieving their pathogen-controlling effects. However, as many of these processes are shared among fungi, fungicide treatments have been reported to have unintended consequences on non-target fungi, including many beneficial groups. For example, copper and azoxystrobin both reduced culturable epiphytic and endophytic fungi in common beans13. Likewise, several fungicides altered the phyllosphere fungal compositions while increasing the population of the brown spot pathogen Septoria glycines in soybeans14.

As new research continues to emerge, there have been increasingly contradictory research reports on off-target impacts of fungicide treatments. For instance, epoxiconazole, a demethylation inhibitor (DMI), suppressed epiphytic fungi on winter wheat15 but penconazole, another DMI fungicide, had minimal impact on the fungal population on grapevine leaves16. Variations in fungicide impacts on non-target fungi in the phyllosphere were also documented in other crops, including wheat17,18,19 soybean9,14 corn9 barley20 and tea21.

Comparatively, research on how repeated fungicide applications may affect the phyllosphere fungal communities has been rather limited, with inconsistent results. With a culture-based approach, Doherty et al.22 showed that repeated applications of a multi-site contact fungicide chemistry - chlorothalonil reduced the total fungal population of the creeping bentgrass phyllosphere in the second year but not in the first year when compared with the nontreated controls. With high-throughput sequencing, Perazzoli et al.16 observed minimal changes in the fungal community on grapevines with 3-weekly treatments of DMI fungicide penconazole. These studies raised some important questions. How, or if, repeated applications of different fungicide chemistries – contact vs. systemic and single- vs. multi-site – differentially impact fungal communities? How broad in scope may multi-site contact fungicide chemistries like chlorothalonil impact fungal communities? Specifically, how may they influence different functional groups in the fungal communities, including plant pathogens and plant and environmentally beneficial microbes? What are the threshold numbers at which repeated applications will result in reduced sensitivity to the same multi-site contact fungicide chemistries? Unlike many single-site systemic fungicides, multi-site contact fungicides are generally considered low risk for resistance development, and their product labels often lack a clear recommendation on the number of applications per season. Mycobiome-based investigations into the above questions will generate data essential to reevaluate current practices in the fungicide labeling, chemical protection and fungicide resistance management programming. Such studies may also provide important leads for understanding the underlying mechanisms by which the reduced sensitivity emerged in the fungal communities as some fungal species have been reported to be responsible for accelerated biodegradation of fungicides after several applications23,24.

Boxwood (Buxus spp. L.) has been long regarded as a low-maintenance crop25 with rising health issues in recent years. Specifically, boxwood blight caused by Calonectria pseudonaviculata was first observed and confirmed in the U.S. in 201126. This new disease has since spread to 30 U.S. states, wiping out many crops at production and historic plantings27,28 and triggering periodic fungicide applications at 2- to 3-week intervals29,30,31. Boxwood dieback caused by Colletotrichum theobromicola first emerged in Louisiana in 201532, and by 2021 it has spread to many other U.S. states33. Likewise, several previously minor diseases such as Volutella blight34,35, Macrophoma leaf spot36, and Phytophthora root and crown rot37,38 have recently emerged and become major health issues, which require fungicide protection depending upon locale39. Among the most commonly-used fungicide chemistries are a multi-site contact chemistry, chlorothalonil, and single-site systemic fungicides in FRAC group 3 represented by propiconazole40. How these fungicides may affect pathogen populations and non-target microorganisms was largely unknown.

In this study, we hypothesized that: (1) Multi-site contact and single-site systemic fungicides differentially perturb phyllosphere epiphytic and endophytic fungal communities; (2) Repeated fungicide applications alter the fungal community composition and functions. To test these hypotheses, we used boxwood as a model plant. We also selected three commonly used fungicides in boxwood nurseries and gardens and evaluated their impacts on boxwood epi- and endophytic fungal communities. The selected fungicides were Daconil Weather Stik (54% chlorothalonil), Banner Maxx (14.3% propiconazole), and Concert II – a combo with 38.5% chlorothalonil and 2.9% propiconazole. Boxwood shoot samples were collected immediately before (0 days) and after (1, 7, and 14 days) fungicide treatments in the spring and summer to examine the short-term and repeated effects of the selected fungicides. Shoot epiphytic and endophytic fungal communities were characterized using Nanopore MinION sequencing on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) amplicons.

Results

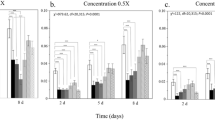

Community α-diversity under different fungicide treatments

Fungicide treatment, season, and their interaction all had significant impact on the community α-diversity (Table 1) and these effects were more pronounced on epiphytes than endophytes. For example, the Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) richness of the epiphytic community was higher in boxwood shoot samples treated with Banner Maxx than in the nontreated control or those treated with Daconil in the spring (Fig. 1). Likewise, the Shannon index of epiphytic community was higher in the samples treated with Daconil and Concert II than those nontreated controls (Figure S2). But in the summer, the OTU richness of the epiphytic community was lower in samples treated with Daconil than the nontreated controls (Fig. 1). Comparatively, fungicide impact on endophytic community was only observed in the summer samples. Specifically, the Shannon index was higher in the samples treated with Banner Maxx than the nontreated controls, and the OTU richness was lower in the samples treated with Daconil than those with Banner Maxx. Sampling time only affected the OTU richness of the endophytic fungal community.

Community structure under different fungicide treatments

Fungicide treatment, season, and their interaction all had significant impact on the epiphytic than endophytic fungal community structure (Table S1), with fungicide treatment being the strongest driver and having more pronounced effect. Specifically, fungicide treatments explained 27.1% and 23.1% of the total variations in epiphyte community structure in spring and summer, respectively (Table 2). PCoA plots demonstrated clearer separations in the epiphytic fungal community among fungicide treatments (Fig. 2). In particular, Daconil- and Concert II-treated samples tended to cluster together while being separated from the nontreated controls and those treated with Banner Maxx. Comparatively, significant fungicide effect on endophytic community structure was only observed in summer, accounting for 17.4% of the total variations (Table 2), without a clear separation among fungicide treatments as observed for epiphytic community (Fig. 2).

Unconstrained principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of the Jaccard dissimilarity in boxwood epiphytic (A and C) and endophytic fungal communities (B and D) at different times of 2021 among four treatments: NT = Nontreated control, DL = Daconil, BM = Banner Maxx, C2 = Concert II. Dashed circles represent 95% confidence ellipse.

Sampling time also affected the fungal community structures in the summer samples. Specifically, it accounted for 11.3% of the total variations in epiphyte community structure, a 2.9% increase from spring (R2 = 0.084). The day 7 and 14 samples formed a cluster which was distant from the day 1 samples in summer (Figure S3), but the separation in the spring was not as clear among the four sampling times. Likewise, sampling time also affected endophytic fungal community structure, accounting for 8.9% of the total variations in summer. Specifically, the day 14 samples were separated from all other samples. However, this sampling time effect was not observed in the spring samples.

Fungal community composition and predominant fungal genera

Greater fungal diversity was observed on the shoot surface than internal tissue. A total of 656 OTUs belonging to 427 genera, 243 families, 106 orders, 35 classes, and 8 phyla were identified in the epiphytic fungal community. Comparatively, only 214 OTUs belonging to 152 genera, 101 families, 49 orders, 18 classes, and 3 phyla were detected in the endophytic fungal community. Among these identified taxa, 129 OTUs belonging to 146 genera, 98 families, 49 orders, 18 classes, and 3 phyla were shared between the epiphytic and endophytic communities. Overall, both epiphytic and endophytic fungal communities were largely represented by Ascomycota (> 80%), followed by Basidiomycota (Figure S4) at the phylum level. Notably, the relative abundance of Basidiomycota increased by 6.7–8.6% in summer across both communities.

Predominant fungal composition differed between epiphytic and endophytic communities at the genus level. Cladosporium, Alternaria, Alternariaster, Shiraia, Meira, Pseudopithomyces, Ramularia, and Aureobasidium dominated the shoot surface (Fig. 3A), while Shiraia, Alternariaster, Alternaria, Pseudolasiobolus, Leptosphaeria, and Cladosporium dominated the internal tissue (Fig. 3B).

Bar plots showing the predominant epiphytic (A) and endophytic (B) fungal composition as affected by fungicide treatments in spring and summer and the tables (right) showing the relative abundance of individual genera and the significance level of their differences among four treatments: NT = Nontreated control, DL = Daconil, BM = Banner Maxx, C2 = Concert II. A prefix of p__ and o__ indicates a higher taxonomic ranking was used for the unidentified or unknown genus, with “p__” standing for Phylum, and “o__” for Order. KW = significance level of differences in each genus or group among the four treatments per Kruskal Wallis test with *=0.05, **=0.01, and ***<0.0001. The highest relative abundance is highlighted in orange for genera or groups if their abundance differed among the four treatments.

Broader impacts of fungicide treatment on the predominant genera were observed in the epiphytic than endophytic communities in the spring while the opposite was seen in the summer. Of the ten predominant epiphytic fungal genera, nine had significant differential abundance in spring and five in summer (Fig. 3). Of the ten predominant endophytic fungal genera, four had significant differential abundance in summer and none were significant in spring. For the epiphytic community, the relative abundance of Meira was the highest in the Daconil-treated samples, while that of the Ramularia, Aureobasidium, and Leptosphaeria was the highest in the nontreated, Banner Maxx, and Concert II-treated samples, respectively (Fig. 3A). For the endophytic community, the relative abundance of Pseudolasiobolus, Leptosphaeria, and an unknown genus from phylum Ascomycota was the highest in the Banner Maxx-treated samples in the summer (Fig. 3B). Notably, the relative abundance of Alternaria was the highest in the Concert II-treated samples across the two communities and seasons.

Fungal compositional responses to fungicide treatments

According to MaAslin2 analyses, fungicides affected more epiphytic than endophytic fungal genera (54 vs. 5) as measured by their abundance between boxwood samples collected before and after treatments, and this impact varied with fungicide chemistry and season (Fig. 4). Specifically, Banner Maxx had a rather limited impact in scope with three epiphytes – Proliferodiscus, Fomitopsis and o_Polyporales in the spring and all being promoted while only one – Jamesdicksonia which was suppressed in the summer (Fig. 5). Comparatively, Daconil and Concert II impacted many more epiphytes with the vast majority of them being suppressed across all three post-treatment sampling times in the spring. Of these two fungicides, Daconil suppressed more epiphytes than Concert II (34 vs. 14) as shown in Fig. 5. However, similar impacts were not observed in the summer. For endophytes, only one genus was promoted in the spring while four genera were enhanced in the summer (data not shown).

Daconil and Concert II had differential impacts on epiphytic community in terms of the membership affected, and the nature, time and duration of effect detected in both seasons (Fig. 5). In the spring, Daconil consistently suppressed more fungal genera than Concert II (23 vs. 3) through all three post-treatment sampling times starting at day 1 and ending at day 14. Only two genera – Amphosoma and Allophylaria were consistently suppressed by both Daconil and Concert II. Among the important genera consistently suppressed by Daconil but not by Concert II post treatment were two plant pathogenic genera, Colletotrichum and Glomerella, and two of the top 10 abundant genera, Ramularia and Vishniacozyma. Four other top 10 genera were also affected by Daconil but not Concert II, with Meira showing reduced abundance at day 1 through 7 post-treatment, and Aureobasidium and Leptosphaeria at day 7 through 14, while Pseudopithomyces only at day 1. Only one epiphyte, Physciella, was consistently suppressed by Concert II but not by Daconil. Comparatively, only one epiphyte, Proliferodiscus, was consistently promoted by both Daconil and Concert II and that promotional impact was observed at day 7 through 14 poster treatment. In the summer, only two epiphytes, Proliferodiscus and Hyphodermmella, were consistently suppressed by Concert II through all three post-treatment sampling times, but this number of affected genera increased to ten by day 14. Comparatively, no epiphyte was suppressed by Daconil at day 1 post-treatment, only three at day 7 and one by day 14. On the other hand, eleven genera were promoted by Daconil whereas only one by Concert II on the same day. Among those promoted genera by Daconil were Colletotrichum and Glomerella, with the former including an emerging boxwood dieback pathogen belongs.

Heatmap of the fungicide impacts on boxwood epiphytic fungal genera 1, 7 and 14 days after fungicide treatment when compared to the pretreatment by season. The color gradient of the heatmap indicates the association or degree of impact, as defined by formula: -log(qval) x sign (coefficient). Cells with promoting effect are coded in red while those with suppressing effect are coded in purple. The top 10 predominant genera are written in red. DL = Daconil Weather Stik, BM = Banner Maxx, C2 = Concert II.

Predicted functional groups and their responses to fungicide treatments

Both epiphytic and endophytic fungal communities were dominated by the functional group ‘Plant Pathogen’, but they differed in other functional groups. On the shoot surface, the relative abundance of the ‘Plant Pathogen’ guild was over 65%, followed by ‘Endophyte-Lichen Parasite-Plant Pathogen-Undefined Saprotroph’ at 7.4%, ‘Plant Pathogen-Undefined Saprotroph’ at 6.3%, ‘Undefined saprotroph’ at 3.0%, ‘Wood Saprotroph’ at 2.5%, and ‘Plant pathogen-Wood saprotroph’ at 2.1% (Fig. 6A). Inside the shoot tissue, the relative abundance of the ‘Plant Pathogen’ guild was over 90%, followed by ‘Ectomycorrhizal-Fungal Parasite’ at 7.3%, and ‘Undefined Saprotroph’ at 0.6%. Notably, the ‘Ectomycorrhizal-Fungal Parasite’ group was represented by mushroom-producing fungi, including two genera Tricholoma and Boletus from the families of Tricholomataceae and Boletaceae, respectively. Similarly, the ‘Ectomycorrhizal-Undefined Saprotroph’ group was represented by mushrooms, including the genus Amanita of the family Amanitaceae and an unknown genus of the family Thelephoraceae (data not shown).

(A) Bar plots showing the most abundant functional groups within the boxwood epiphytic and endophytic fungal communities in spring and summer. Differetially abundant functional groups in epiphytic and endophytic communities were indicated by an arrow on the left and right, respectively, with increase in abundance from sping to summer being marked with green arrow pointed up and decrease in abundance being marked with a red arrow pointed down. For groups with multiple functions, those functions are seperated by ‘-’. (B) Heatmap of fungicide impacts on the relative abundance of the epiphtic functional groups 1, 7, and 14 days after treatment as compared to the pretreatment in sping and summer. The most abundant functional groups are written in red. The color gradient of the heatmap indicates the association or degree of change, as defined by formula: -log(qval) x sign (coefficient). The cells with a promoting effect are coded in red while those with a suppressing effect are coded in purple. DL = Daconil, BM = Banner Maxx, C2 = Concert II.

Both Daconil and Concert II had more inhibitory impacts on the epiphytic functional groups in spring than in summer. In the spring, Daconil suppressed seven guilds at all three post-treatment sampling times when compared to the pretreatment (Fig. 6B). These guilds included highly abundant ‘Plant Pathogen-Undefined Saprotroph’ and ‘Wood Saprotroph’, and some less abundant guilds, such as ‘Endophyte-Plant Pathogen’ and ‘Animal Pathogen-Plant Pathogen-Undefined Saprotroph’. Similarly, Concert II suppressed two guilds at all three post-treatment sampling times when compared to the pretreatment, including ‘Orchid Mycorrhizal’ and ‘Lichenized’. In the summer, Concert II suppressed two guilds at all three post-treatment sampling times when compared to the pretreatment. These included highly abundant ‘Plant Saprotroph’ and ‘Plant Pathogen-Wood Saprotroph’. Comparatively, Daconil was rather promotive at 14 days after treatment. Notably, the most abundant ‘Plant Pathogen’ guild was promoted by Daconil but suppressed by Banner Maxx seven days after treatment in spring. However, in the summer, this guild was suppressed by Daconil one day after treatment but promoted by Concert II seven days after treatment, and no effect of Banner Maxx was observed over time.

Effects of season and repeated fungicide application on the fungal community

Seasonal changes without fungicide perturbations

There were significant seasonal changes in the epiphytic fungal community from spring to summer when comparing the nontreated boxwood samples taken on August 25 to those on May 26. Specifically, 41 genera had increased relative abundance and four genera had reduced relative abundance in the summer when compared to the spring, while 21 genera remained unchanged in their relative abundance between the two seasons (Fig. 7). Among the genera with increased abundance were seven of the ten most abundant genera – Pseudopithomyces, o_Helotiales, Ramularia, Meira, Peniophora, Leptosphaeria and p__Ascomycota, and some important plant pathogens – Volutella and Colletotrichum/Glomerella (Fig. 8A). Two of the ten most abundant genera – Shiraia and Aureobasidium had reduced abundance in the summer when compared to the spring.

There were also significant seasonal changes in the functional groups of the epiphytic fungal community when comparing the nontreated boxwood samples taken on August 25 to those on May 26. In summary, 14 functional groups increased and only two reduced in relative abundance in the summer when compared to the spring, while eight functional groups remained unchanged in relative abundance between the two seasons (Fig. 7). Among the functional groups with increased relative abundance were six of the ten most abundant functional groups – ‘Endophyte-Lichen Parasite-Plant Pathogen-Undefined Saprotroph’, ‘Plant Saprotroph’, ‘Undefined Saprotroph’, ‘Soil Saprotroph’, ‘Epiphyte’, and ‘Plant Pathogen-Wood Saprotroph’ (Fig. 8B). Two of the ten most abundant functional groups – ‘Plant Pathogen’ and ‘Fungal Parasite-Litter Saprotroph’ had reduced abundance in the summer when compared to the spring.

Heatmaps showing the epiphytic fungal genera (A) and function groups (B) with /without significant changes in relative abundance (RA) when comparing pretreatment boxwood samples taken on August 25 (summer) to those on May 26 (spring). The color gradient of the heatmap indicates the association or degree of impact, as defined by formula: -log(qval) x sign (coefficient). Red cells indicate increased RA in summer compared to spring while those with purple cells indicate the opposite. The top 10 predominant genera or functions are written in red. NT = Nontreated, DL = Daconil Weather Stik, BM = Banner Maxx, C2 = Concert II.

Two functional groups in the endophytic fungal community changed significantly when comparing the nontreated boxwood samples taken on August 25 to those on May 26. The relative abundance of the group ‘Plant Pathogen’ was reduced while the group ‘Ectomycorrhizal-Fungal Parasite’ was increased in summer compared to spring (Figure S5).

Repeated fungicide applications impacted community composition and functional groups

Significant changes were observed in the epiphytic fungal composition from spring to summer following repeated fungicide applications starting on April 12 with Daconil at 2-week intervals while Banner Maxx and Concert II at 3-week intervals. More fungal genera were suppressed by at least one fungicide (Fig. 7). Specifically, two genera, Vishniacozyma and Irpex, were suppressed by all three fungicides (Fig. 8A). Four genera, including Orbilia, Amphosoma, Schizophyllum, and an unknown Ascomycota genus, were suppressed by both Daconil and Concert II. Fifteen genera, including Acidomyces, Kockovaella, Colletotrichum/Glomerella, were suppressed by Daconil alone. Likewise, two genera, Parmotrema and Physciella, were suppressed by Concert II alone while three genera, including Tremella, Holtermannia, and Sporobolomyces were suppressed by Banner Maxx alone. Comparatively, fewer fungal genera were promoted by fungicides (Fig. 7). For instance, two genera, Jamesdicksonia and Uwebraunia, were enhanced by Banner Maxx and one, Hyphodermella, by Concert II while none were promoted by Daconil (Fig. 8A). Additionally, one genus, Libertella, was promoted by both Daconil and Concert II while another, Phyllozyma, was enhanced by all three fungicides. In contrast, the composition of the endophytic fungi was not affected by repeated fungicide applications from spring to summer (data not shown).

Similar changes were observed in functional groups of the epiphytic fungal community as affected by repeated fungicide applications from spring to summer. More functional groups were suppressed by at least one fungicide (Fig. 7). Particularly, ‘Wood Saprotroph’ and ‘Lichenized’ fungi were suppressed by all three fungicides (Fig. 8B). Two functional groups, ‘Plant Pathogen-Wood Saprotroph’ and ‘Endophyte-Plant Pathogen-Undefined Saprotroph’, were suppressed by both Daconil and Concert II. Nine functional groups, including the two most abundant ‘Epiphyte’ and ‘Plant Pathogen-Undefined Saprotroph’ were suppressed by Daconil alone. Similarly, three function groups, ‘Dung Saprotroph-Nematophagous’, ‘Ectomycorrhizal-Undefined Saprotroph’, and Orchid Mycorrhizal’, were suppressed by Concert II alone. Comparatively, fewer functional groups were promoted by fungicides (Fig. 7), with only ‘Ectomycorrhizal-Fungal Parasite’ being promoted by Banner Maxx (Fig. 8B).

Comparatively, lesser impact was seen in functional group of the endophytic fungal community by repeated fungicide applications. Specifically, ‘Undefined Saprotroph’ was promoted by both Banner Maxx and Concert II (Figure S5). The abundance changes of ‘Ectomycorrhizal-Fungal Parasite’ and ‘Plant Pathogen’ was the same for Daconil-treated and the nontreated samples.

Changes in fungal community co-occurrence network from spring to summer

Per analyses of all nontreated boxwood samples taken four times over a 14-day period in the spring and summer, slight changes were observed in both epiphytic and endophytic fungal communities. Specifically, a higher number of positive associations were observed in the summer than in the spring (Table 3). The connectivity of the most central nodes (i.e., genera), indicated by the node degree and betweenness, was also increased in the summer when compared to the spring.

Comparatively, all three fungicides affected the co-occurrence networks of the fungal community with the most extensive effects on those of endophytic fungal community by Daconil. Particularly, network connectivity and modularity indicators, including the size of the large connect components, network modularity, edge density, natural connectivity, vertex connectivity, and edge connectivity were all higher in the summer than in the spring with Daconil treatment and these properties did not change in the nontreated samples (Table 3).

More hub genera were identified in the summer than spring in both epiphytic (3 vs. 2) and endophytic fungal networks (2 vs. 4) (Table 4 and Figures S6 and S7). However, these genera were rather distinct to each season and fungicide treatment.

Discussion

This study produced several major findings. First, fungal communities were much more diverse on the surface than in the internal tissue of boxwood shoots, with Shiraia as one of the most abundant genera in both endophytic and epiphytic communities. Second, plant pathogen was by far the largest functional group predicted in both epiphytic and endophytic fungal communities. Third, the three fungicides assessed in this study did not have strong effect on the plant pathogen group, but they did impact other functional groups in the epiphytic fungal community. Fourth, fungicide treatments affected fungal community α- and β- diversity and composition, with broader and more profound effects on the epiphytes than the endophytes. Fifth, Daconil and Concert II, two primarily contact fungicides containing chlorothalonil as their sole or major active ingredient (AI), had more extensive and marked impact on the epiphytic community than Banner Maxx, a systemic fungicide with propiconazole as its AI. Sixth, the chemical impact on the epiphytic community generally increased with increasing chlorothalonil concentration in the product. Seventh, repeated fungicide applications not only altered the composition and function of epiphytic fungal community but also reduced the community sensitivity to the same fungicide chemistry late in the season. These findings significantly advanced boxwood biology and the understanding of fungicide resistance development with important practical implications.

The present study generated the first mycobiome evidence supporting boxwood as a long regarded low maintenance iconic landscape plant. Boxwood has a distinct endophytic fungal community with Shiraia being the most abundant. Shiraia was also among the most abundant in the epiphytic community. This genus has so far been isolated only from bamboos (Bambusoideae) and firmoss (Huperzia serrata) in east Asia42,43,44. Shiraia produces a range of secondary metabolites (e.g., hypocrellins A and huperzine A) with antimicrobial, anticancer, and anticholinesterase activities44,45. Because of its high abundance in both endophytic and epiphytic communities and metabolic potentials, Shiraia may play a critical role in enabling its host boxwood to endure biological and environmental stresses while tolerating frequent pruning and training25. It is worth noting that Shiraia was not reported in a recent study documenting isolation and evaluation of several boxwood endophytes for their biological control and plant growth promoting potential46. There were several major differences between the previous and present studies. First, 5-year-old field-grown boxwood cultivar ‘Vardar Valley’ was used in this study while liners of English boxwood (B. sempervirens ‘Suffruticosa’) grown in small plastic containers with soil-less potting mix was used in the previous study46. Second, this study used a culture-independent method while the previous study was culture based. Whether boxwood cultivar, plant age, method used, and/or any other factors that may have contributed to this discrepancy in detecting Shiraia between the two studies is unknown. Considering Shiraia’s abundance in ‘Vardar Valley’ boxwood and its ability to produce metabolites of significant health benefits, further investigations are warranted to (1) determine the presence of Shiraia in other boxwood cultivars; (2) obtain isolates and their secondary metabolites of this genus; and (3) assess their potential for improving boxwood and human health.

This study provided important new insights into the increasing health issues with boxwood, while adding fresh evidence on fungicides’ off-target effects. First, Alternariaster is another abundant endophytic and epiphytic fungus identified in the present study. This genus contains many leaf spot-causing pathogens47. Comparatively, boxwood has a less distinct epiphytic fungal community when compared to that of other plants15,48 with Cladosporium and Alternaria being the two other most abundant genera. These two Ascomycota fungi have many species that are pathogens and saprotrophs49 but they are not known to cause boxwood disease. However, both Shin et al.36 and Kurzawińska et al.50 showed that these two fungal genera are frequently isolated from the diseased boxwood leaves and stems, especially Alternaria. FUNGuild analysis showed that plant pathogens were by far the largest functional groups on the boxwood shoot surface and the internal tissue. Their presence may have overloaded the host’s innate immunity and increased the energy cost of boxwood defense reactions15,51 predisposing boxwood to disease invasion. Second, three fungicides, in particular of Daconil and Concert II, suppressed many saprotroph groups, but they only had weak effect on that of the plant pathogens at most. Fungal saprotrophs have been previously shown to be sensitive to fungicides17 and they may have antagonistic property against pathogens52. Some of the repressed epiphytic genera, including yeasts, may possess properties in mitigating environmental stresses for plants. For example, Aureobasidium pullulans produces extracellular polysaccharides and melanin53 and has been shown to alleviate plants from drought stress54 and UV damage55. The absence of these fungi may also result in a biological vacuum wherein plant pathogens can recolonize the vacant niche rapidly56. Third, fungicide treatments altered the epiphytic and endophytic community diversity, structure, and co-occurrence networks, breaking the balance in microbial composition and association in the boxwood phyllosphere, termed as dysbiosis57. Microbial dysbiosis is linked to plant stress or disease58. Runge et al.59 found that dysbiotic leaves harbored more plant pathogens while healthy leaves contained more plant beneficial microbes in wild tomato species. As expected, fungicide treatment had broader and more marked impacts on the epiphytes than endophytes because the former come into direct contact with the fungicidal compounds on the shoot surface while the latter are sheltered by the plant cuticles and other structures. Though, it is worthwhile noting that both Daconil and Concert II, along with Banner Maxx, also affected the endophytic fungal community composition and association, including the connectivity and modularity of the endophytic fungal networks, and the effects were more marked in the summer than in the spring samples, indicating that the endophytic fungal community changed over time upon fungicide applications. Yet, the impact of contact fungicide on the endophytic fungal community was not unexpected because a fraction of commercially formulated chlorothalonil can penetrate into the cuticular wax and internal tissue 24 h after application60. Similar observations were previously made with other contact fungicides. Specifically, Prior et al.13 reported that copper- and sulfur-based contact fungicides affected the culturable endophytic fungi in common bean. Previously studies have also reported other contact and systemic fungicides reshape the phyllosphere fungal community composition and structure in soybean9,14, maize9, common and broad beans13, wheat17, grapevine61, and tomato62. However, changes in the epiphytic community may impact the assembly of endophytic fungal community, as many endophytes originate from the plant surface63 to not only establish intimate relationship with the host plant but also promote host plant growth and health64.

The selection of three fungicides with two active ingredients provided a unique window for examining how their modes of action and concentrations may impact the phyllosphere mycobiome. Multi-site contact fungicide Daconil with 54% chlorothalonil as its sole AI had broader and more pronounced inhibitory effects on the epiphytes than the other fungicide products assessed in this study. Doherty et al.22 also reported that chlorothalonil reduced the total culturable fungal population in the phyllosphere of creeping bentgrass. Comparatively, single-site systemic Banner Maxx with 14.3% propiconazole as its sole AI had limited but rather promoting effect on boxwood epiphytic and endophytic fungal communities, particularly on the epiphytic fungal community richness in spring and endophytic fungal community diversity in summer. This may be a result of propiconazole’s single-site mode of action being limited in targeting a diverse fungal population and that the boxwood phyllosphere may naturally harbor propiconazole-tolerant fungal species as reported in grass65, such as those from Cladosporium. Nevertheless, the result is in agreement with many previous studies evaluating the effect of propiconazole or other DMI fungicides on wheat17,18, grape16, and barley crop microbiome20. Interestingly, Concert II, containing 38.5% chlorothalonil (or 71% of that in Daconil) and 2.9% propiconazole (or 20% of that in Banner Maxx) impacted the epiphytes to a lesser degree than Daconil but significantly more than Banner Maxx. This observation suggests that chlorothalonil concentration was another key factor affecting fungicide effect on the phyllosphere mycobiome, consistent with previous studies on wheat18 and soil66. These results suggest that when chemical protection is deemed necessary, single-site systemic fungicides should be considered first to fully leverage and utilize the natural mycobiome in crop health management. Likewise, where multi-site contact fungicides must be used, their concentrations should be carefully considered with preference given to a low rate by using mixed chemistry like Concert II instead of sole chemistry of Daconil. Towards these goals, all other fungicides as well as other agrochemicals should be evaluated for their impacts on mycobiome and other microbial communities, and this information should be included in the product labels to help farmers and gardeners to make informed decisions in selecting agrochemicals for crop production and gardening. This information is equally useful for chemical companies to make informed decisions in formulating and marketing of the existing and new chemistries to better position their products in increasingly microbiome-based agricultural and horticultural industries. Agrochemical companies may follow suit of Syngenta to work with research institutions, as was done in this study, or conduct evaluations in their own research labs where applicable.

This study produced the first microbiome-based evidence that demonstrates that repeated chlorothalonil treatments structurally and functionally altered the epiphytic fungal community with many genera becoming less sensitive to the same chemistry late in the season. With Daconil as an example, 23 genera remained unchanged or even increased in their relative abundance 1, 7, or 14 days after the eighth application. These observations sharply contrasted with what was observed 1, 7 and 14 days after the fourth application on May 26 – their abundance all being consistently reduced (Fig. 5). It is worth pointing out the lasting effect of the first seven Daconil treatments as the epiphytic fungal community did not bounce back after a 50-day treatment gap from July 6 to August 24. This shift is indicative of reduced sensitivity of these fungal genera to chlorothalonil after eight applications from April 12 to August 25. Among these 23 genera were some important plant pathogens, including Ramularia, Colletotrichum and its sexual stage Glomerella. Specifically, Colletotrichum theobromicola32 has recently been identified as the causal agent of boxwood dieback, a new and emerging destructive disease. Similarly, leaf spot caused by Ramularia species is becoming a major issue in barley67 and sugar beet68, although not yet on boxwood. Katsoula et al.23 reported accelerated degradation of a single-site contact fungicide iprodione in the phyllosphere of pepper plants after four applications at 30-day intervals and they correlated with the chemical degradation by Alternaria. This is the first report of reduced sensitivity of diverse fungi to a multi-site contact fungicide that has long been regarded as low risk in resistance development. We observed that Alternaria became more abundant in Daconil-treated boxwood than those nontreated controls in both spring and summer in this study (Fig. 3A). A similar increase in Alternaria abundance was also seen in boxwood treated with Concert II that contains 38.5% of chlorothalonil, plus 2.9% of propiconazole. Whether similar chemical degradation by Alternaria occurred from chlorothalonil application late in the season is not known at this time. Nevertheless, these observations together challenge a long-time assumption that multi-site contact fungicide is low risk for resistance development. Further investigations to test this hypothesis are urgently needed, considering the potentially broad impacts on managing fungicide resistance, and developing crop health and production programs. Likewise, investigations into whether the emergence of boxwood dieback is caused by increased use of Daconil for control of another important disease, boxwood blight, are warranted. These studies are essential to developing a systems approach to boxwood health and production.

The results of the present study also provide understanding for the potential negative impacts of repeated fungicide applications on environmental health from several perspectives. For example, many saprotrophs that were negatively impacted by repeated fungicide treatments, especially by Daconil, are key regulators of nutrient cycling69 in addition to antagonizing against pathogens described above. Likewise, those lichenized fungi affected by fungicides are symbionts with plants and algae, which are keystone species in ecosystem70. Thus, repeated fungicide applications may impact ecosystem health, as microorganisms and their roles are closely connected to the wellbeing of all other living organisms—a perspective emphasized by the One Health concept71.

Conclusions

This study uncovered diverse fungal communities in boxwood shoots, providing the first mycobiome evidence supporting the low-maintenance nature of this iconic landscape plant. It also demonstrated that repeated applications of multi-site fungicide chemistries like chlorothalonil affect epiphytic fungal community with many genera becoming less sensitive to the same chemistry late in the season. This discovery challenges a long-time notion that multi-site fungicides are low risk in resistance development while providing important insights into boxwood’s rising health issues in recent years.

Methods

Study site, Boxwood crop, key cultural practices and weather parameters

This study was added to an existing field trial that started on April 12, 2021, with 5-year-old field-grown Buxus sempervirens ‘Vardar Valley’ in western North Carolina. Individual boxwood plants were approximately 60 cm in height and 40–50 cm in width at the beginning of the trial. This boxwood cultivar grows at a rate of 2.5 to 7.6 cm per year72. Fertilizer was applied in early April and two herbicides, Roundup® (Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany) and Goal® (Nutrichem Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), were applied in late May. The average daily temperature was 21.5 °C and 23.3 °C, and the total precipitation was 46.2 mm and 38.1 mm during the two 14-day sampling periods in the spring and summer, respectively (see supplemental materials for details on weather data source).

Fungicide treatments, Boxwood sampling and sample processing

Three fungicides - Banner Maxx®, Daconil Weather Stik®, hereafter referred as Daconil, and Concert II® were used in this study (Table 5). These three fungicides, plus a nontreated control, were arranged in a randomized complete block design and applied to four replicate plants per treatment. The first application of all three fungicides was performed on April 12, 2021 with subsequent applications of Daconil at 2-week intervals, and Banner Maxx and Concert II at 3-week intervals. As a result, three subsequent coinciding applications of three fungicides were May 26, July 5, and August 25. To mimic the commercial production no fungicide was applied from July 6 to August 24 when disease pressure was generally low due to hot weather conditions that are suppressive for the prevailing disease – boxwood blight73,74,75.

The first batches of boxwood shoot samples were collected immediately before the second coinciding fungicide application on May 26, and 1, 7, and 14 days after (Fig. 9); hereafter these samples are referred to as the spring samples with those taken on May 26 as day 0 while others as day 1, 7 or 14 correspondingly. The day 0 spring samples received 3 applications of Daconil and 2 applications of Banner Maxx or Concert II. All day 1, 7 and 14 spring samples received one more application of the same fungicides – four applications for Daconil and three applications for Banner Maxx and Concert II. Nontreated boxwood shoot samples were also collected at each of the four sampling times. Each replicate sample included fifteen 7-cm long boxwood shoots taken from each plant, and all samples were processed as detailed previously76.

The second batches of samples were collected immediately before and after the fourth coinciding application of all three fungicides on August 25; hereafter these samples are referred to as the summer samples. Due to skipping fungicide applications from July 6 to August 24, the day 0 summer samples received seven applications of Daconil, or five applications of Banner Maxx or Concert II. Likewise, the summer day 1, 7 and 14 samples received eight applications of Daconil or six applications of Banner Maxx or Concert II correspondingly. Again, nontreated controls never received any fungicide treatment during this study. All summer samples were collected and processed as described above.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Five healthy boxwood shoots were arbitrarily selected from each replicate sample and processed for DNA extraction from the surface washings and surface-sterilized shoot tissues to differentiate epiphytic and endophytic microbial communities, respectively, following the previous protocol76.

The NSA3 and NLC2 primer pair77 (see Table S2) was used to amplify the full-length internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions including ITS1, 5.8 S, and ITS2, plus partial SSU and LSU rDNA for fungal identification. PCR ingredients and thermal condition are described in the supplemental materials.

Nanopore library preparation, and sequencing

Nanopore sequencing library barcoding and preparation followed our previous study76. Equimolar portions of sixteen ITS amplicon barcoded samples were pooled. For each sequencing run, an aliquot of 40 fmol (34.6 ng of 1400 bp) of the DNA library was loaded to a MinION R9.4 flow cell following Nanopore’s priming and loading protocols.

Bioinformatics

Live base-calling used the software MinKNOW (ONT, core version 4.4.3) and was coupled with Guppy (GPU version 5.0.11). Read quality was filtered to Q9 and read length was kept between 1000 bp and 2000 bp. The FASTQ read outputs were then subjected to a customized python package NanoPrep78 (version 0.19.1) for further quality checking, barcode trimming, and sample grouping as described in our previous study76. Chimera removal and alignment-based fungal taxonomy assignment followed the steps in Cuscó et al.79 using the “UNITE + INSD” database (version 8.3 for fungi)80 and the Minimap2 aligner81 (See supplemental materials for details). In this study, we adopted the term “Operational Taxonomic Unit” (OTU) to describe those taxonomy-assigned amplicon sequences, which was annotated by the best alignment after Minimap2; this is different from the conventional “cluster by a threshold” definition82.

Statistical analyses

Epiphyte and endophyte OTU tables were further pruned to exclude potential sequencing artifacts, with samples containing more than 5,000 reads and OTU with more than 5 reads across all samples were retained. Unidentified fungi and ambiguous annotations (see supplemental materials) were re-classified to the lowest possible rank using the format_to_besthit function from the microbiome package (version 1.16.0)83. The significance level was set at 0.05 for all statistical analyses unless otherwise stated.

Fungal community α-diversity

OTU richness and Shannon index were used to assess fungal community α-diversity. Both the OTU tables for epiphytic and endophytic fungal communities were rarefied to 10,000 sequences, retaining 118 and 112 samples, respectively. This rarefaction depth recovered most of the α-diversity information without discarding many samples. Three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the effect of fungicide treatment, sampling time, season, and their interactions on the α-diversity. The residuals of ANOVA were normally distributed. Differences among the post fungicide treatments were compared using Dunn’s Multiple Comparisons84 for the epiphytic and endophytic in spring and summer, respectively. Using the same method, the effect of the four sampling times on microbial α-diversity of fungicide treated samples was also analyzed. P values were adjusted using the Holm-Bonferroni method. The microeco package85 was employed during the analysis and plotting.

Fungal community structure analyses

The Jaccard dissimilarity index was used to measure fungal community structure86. The OTU tables were first transformed to relative abundance by the Hellinger transformation87 which is often used for multivariate analyses of compositional data88. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was used to ordinate the dissimilarity matrix and help visualize clustering among fungicide treatments and sampling times in both seasons using the plot_ordination function of the phyloseq package (version 1.38.0)89. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed on the Jaccard dissimilarity matrix to evaluate effects of fungicide, sampling time, and their interactions using the adonis function with 10,000 permutations90. Bray-Curtis similarity index91 was also used to examine fungal community structure and its results were similar (Table S3).

Fungal community composition analyses

Differential abundance was analyzed at the genus level using the Microbiome Multivariable Association with Linear Models (MaAsLin2) package92 (version 1.8.0) in R. The OTU table was first normalized to relative abundance, the minimal abundance was set to 0.1%, and the minimal prevalence was set at 0. The data was then transformed using a variance-stabilizing arcsin square root transformation (AST) method. Fungicide treatment was fit to the default linear model as fix effect for each of the three sampling time points for spring and summer. Nontreated treatment was set as the baseline. P-values were corrected using the false discovery rate (FDR)93 at the default setting of 0.2594. Fungal genera with significant association or abundance differences were visualized in a heatmap using the package ComplexHeatmap95. To evaluate how repeated fungicide application may affect fungal composition, pretreatment samples collected in spring and summer were compared using MaAsLin2 for each treatment. The dynamics were also visualized with a heatmap.

Fungal community function prediction and analysis

The FUNGuild database (version 1.1)49 was used to predict the functional groups (or guilds) in the fungal communities. This database included 13,000 fungal taxa and contained annotations of fungal ecological guilds compiled from literature. Guilds with confidence ranking “Probable” and “Highly Probable” were kept. A Kruskal Wallis test was used for epiphytic and endophytic communities in spring and in summer, respectively. The P values were adjusted using the Benjamini Hochberg method. MaAslin2 was again implemented with the same parameters to compare the relative abundance of functional groups at each post treatment time to the pretreatment time for each treatment in each of the two seasons. To evaluate whether fungicides may also have lasting effect on the community functions, the relative abundance of the functional groups between spring and summer at pretreatment time was compared using MaAsLin2 for each treatment. The dynamics were visualized with a heatmap.

Co-occurrence network analyses

The NetComi package (version 1.0.3)96 was used to construct networks at the genus level implementing the Semi-Parametric Rank-based approach for INference in Graphical model (SPRING)97 algorithm with “nlamba” being set to 100, “rep.num” to 100, and “Rmethod” to “approx”. The top 80 most abundant fungal genera were included. Hub taxa were determined by 95% quantile of the nodes with highest degree, betweenness, and closeness centrality measures. A fast greedy modularity-based algorithm (cluster_fast_greedy)98 was used for node clustering. The centrality measurements of degree, betweenness, closeness, and eigenvector were normalized and network pairwise comparison was performed using 1,000 permutations. Similarity of the most central nodes was measured using the Jaccard index99 taking values from 1 (two equal sets of the most central nodes) to 0 (two different sets of the most central nodes). Similarity of clustering between two compared networks was measured using the adjusted rand index (ARI)100 taking values from − 1 (less similar cluster partitions) and 1 (similar cluster partitions). The null hypothesis of ARI testing assumes ARI equals to zero. P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure101.

Data availability

The FASTQ reads used for data analysis are stored in the European Nucleotide Archive under project accession: PRJEB57951.

References

Leach, J. E., Triplett, L. R., Argueso, C. T. & Trivedi, P. Communication in the phytobiome. Cell 169, 587–596 (2017).

Stone, B. W. G., Weingarten, E. A. & Jackson, C. R. The role of the phyllosphere microbiome in plant health and function. in Annual Plant Reviews Online 533–556 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119312994.apr0614 (2018).

Rodriguez, R. J. & Redman, R. S. Fungal life-styles and ecosystem dynamics: biological aspects of plant pathogens, plant endophytes and saprophytes. in Advances in Botanical Research (eds Andrews, J. H., Tommerup, I. C. & Callow, J. A.) vol. 24 169–193 (Academic, (1997).

Baron, N. C. & Rigobelo, E. C. Endophytic fungi: a tool for plant growth promotion and sustainable agriculture. Mycology 13, 39–55 (2022).

Di Francesco, A. et al. Biocontrol activity and plant growth promotion exerted by Aureobasidium pullulans strains. J. Plant. Growth Regul. 40, 1233–1244 (2021).

Albrectsen, B. R. et al. Endophytic fungi in European Aspen (Populus tremula) leaves—diversity, detection, and a suggested correlation with herbivory resistance. Fungal Divers. 41, 17–28 (2010).

Cambon, M. C. et al. Drought tolerance traits in Neotropical trees correlate with the composition of phyllosphere fungal communities. Phytobiomes J. 7:2, 244-258 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1094/PBIOMES-04-22-0023-R

Bettenfeld, P., Fontaine, F., Trouvelot, S., Fernandez, O. & Courty, P. E. Woody plant declines. What’s wrong with the microbiome? Trends Plant. Sci. 25, 381–394 (2020).

Noel, Z. A. et al. Non-target impacts of fungicide disturbance on phyllosphere yeasts in conventional and no-till management. ISME Commun. 2, 19 (2022).

Castañeda, L. E., Miura, T., Sánchez, R. & Barbosa, O. Effects of agricultural management on phyllosphere fungal diversity in vineyards and the association with adjacent native forests. PeerJ 6, e5715 (2018).

Varanda, C. M. R. et al. Fungal endophytic communities associated to the phyllosphere of grapevine cultivars under different types of management. Fungal Biol. 120, 1525–1536 (2016).

Paasch, B. C. & He, S. Y. Toward Understanding microbiota homeostasis in the plant Kingdom. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009472 (2021).

Prior, R., Mittelbach, M. & Begerow, D. Impact of three different fungicides on fungal epi- and endophytic communities of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and broad bean (Vicia faba). J. Environ. Sci. Health B. 52, 376–386 (2017).

Lin, H. A. & Mideros, S. X. The effect of Septoria Glycines and fungicide application on the soybean phyllosphere mycobiome. Phytobiomes J. 7:2, 220-232 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1094/PBIOMES-12-21-0075-R

Bertelsen, J. R., De Neergaard, E. & Smedegaard-Petersen, V. Fungicidal effects of azoxystrobin and Epoxiconazole on phyllosphere fungi, senescence and yield of winter wheat. Plant. Pathol. 50, 190–205 (2001).

Perazzolli, M. et al. Resilience of the natural phyllosphere microbiota of the grapevine to chemical and biological pesticides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 3585–3596 (2014).

Karlsson, I., Friberg, H., Steinberg, C. & Persson, P. Fungicide effects on fungal community composition in the wheat phyllosphere. PLoS ONE. 9, e111786 (2014).

Knorr, K., Jørgensen, L. N. & Nicolaisen, M. Fungicides have complex effects on the wheat phyllosphere mycobiome. PLOS ONE. 14, e0213176 (2019).

Sapkota, R., Knorr, K., Jørgensen, L. N., O’Hanlon, K. A. & Nicolaisen, M. Host genotype is an important determinant of the cereal phyllosphere mycobiome. New. Phytol. 207, 1134–1144 (2015).

Milazzo, C. et al. High-throughput metabarcoding characterizes fungal endophyte diversity in the phyllosphere of a barley crop. Phytobiomes J. 5, 316–325 (2021).

Win, P. M., Matsumura, E. & Fukuda, K. Effects of pesticides on the diversity of endophytic fungi in tea plants. Microb. Ecol. 82, 62–72 (2021).

Doherty, J. R., Botti-Marino, M., Kerns, J. P., Ritchie, D. F. & Roberts, J. A. Response of microbial populations on the creeping bentgrass phyllosphere to periodic fungicide applications. Plant. Health Prog. 18, 44–49 (2017).

Katsoula, A., Vasileiadis, S., Sapountzi, M. & Karpouzas, D. G. The response of soil and phyllosphere microbial communities to repeated application of the fungicide iprodione: accelerated biodegradation or toxicity? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 96, fiaa056 (2020).

Baumann, A. J. et al. High tolerance and degradation of fungicides by fungal strains isolated from contaminated soils. Mycologia 114, 813–824 (2022).

Batdorf, L. R. Boxwood Handbook: A Practical Guide To Knowing and Growing Boxwood (American Boxwood Society, 1995).

Ivors, K. L. et al. First report of Boxwood blight caused by Cylindrocladium pseudonaviculatum in the united States. Plant. Dis. 96, 1070–1070 (2012).

Daughtrey, M. L. Boxwood blight: threat to ornamentals. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 57, 189–209 (2019).

Hong, C. Fighting plant pathogens together. Science 365, 229–229 (2019).

LaMondia, J. A. Management of Calonectria pseudonaviculata in Boxwood with fungicides and less susceptible host species and varieties. Plant. Dis. 99, 363–369 (2015).

LaMondia, J. A. Fungicide efficacy against Calonectria pseudonaviculata, causal agent of Boxwood blight. Plant. Dis. 98, 99–102 (2014).

LaMondia, J. A. Curative fungicide activity against Calonectria pseudonaviculata, the Boxwood blight pathogen. J. Environ. Hortic. 38, 44–49 (2020).

Singh, R. & Doyle, V. P. Boxwood dieback caused by Colletotrichum theobromicola: A diagnostic guide. Plant. Health Prog. 18, 174–180 (2017).

Kaur, H., Singh, R., Doyle, V. & Valverde, R. A diagnostic TaqMan real-time PCR assay for in planta detection and quantification of Colletotrichum theobromicola, causal agent of Boxwood dieback. Plant. Dis. 105, 2395–2401 (2021).

Yang, X. et al. A diagnostic guide for volutella blight affecting Buxaceae. Plant. Health Prog. 22, 578–590 (2021).

Baysal-Gurel, F., Bika, R., Avin, F. A., Jennings, C. & Simmons, T. Occurrence of volutella blight caused by Pseudonectria foliicola on Boxwood in Tennessee. Plant. Dis. 105, 2014 (2021).

Shin, S., Kim, J. E. & Son, H. Identification and characterization of fungal pathogens associated with Boxwood diseases in the Republic of Korea. Plant. Pathol. J. 38, 304–312 (2022).

Akıllı Şimşek, S., Katırcıoğlu, Y. Z., Çakar, D., Rigling, D. & Maden, S. Impact of fungal diseases on common box (Buxus sempervirens L.) vegetation in Turkey. Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 153, 1203–1220 (2019).

Vettraino, A. M., Franceschini, S. & Vannini, A. First report of Buxus rotundifolia root and collar rot caused by Phytophthora Citrophthora in Italy. Plant. Dis. 94, 272–272 (2010).

Parajuli, M., Neupane, S., Liyanapathiranage, P. & Baysal-Gurel, F. Comparative performance of fungicides in management of Phytophthora root rot on Boxwood. (2023). https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI17227-23

Boxwood blight task force. (2024). https://www.ext.vt.edu/content/ext_vt_edu/en/agriculture/commercial-horticulture/boxwood-blight.html. Accessed July 1.

Edgington, L. V. Systemic fungicides: A perspective after 10 years. Plant. Dis. 64, 19 (1980).

Morakotkarn, D. et al. Taxonomic characterization of Shiraia-like fungi isolated from bamboos in Japan. Mycoscience 49, 258–265 (2008).

Cheng, T. F., Jia, X. M., Ma, X. H., Lin, H. & Zhao, Y. H. Phylogenetic study on Shiraia bambusicola by rDNA sequence analyses. J. Basic. Microbiol. 44, 339–350 (2004).

Zhu, D., Wang, J., Zeng, Q., Zhang, Z. & Yan, R. A novel endophytic huperzine A–producing fungus, Shiraia sp. Slf14, isolated from Huperzia serrata. J. Appl. Microbiol. 109, 1469–1478 (2010).

Lin, X. et al. Transferrin-modified nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy enhance the antitumor efficacy of hypocrellin A. Front Pharmacol 8:815 (2017).

Kong, P., Sharifi, M., Bordas, A. & Hong, C. Differential tolerance to Calonectria pseudonaviculata of english Boxwood plants associated with the complexity of culturable fungal and bacterial endophyte communities. Plants 10, 2244 (2021).

Alves, J. L., Woudenberg, J. H. C., Duarte, L. L., Crous, P. W. & Barreto, R. W. Reappraisal of the genus Alternariaster (Dothideomycetes). Persoonia 31, 77–85 (2013).

LeBlanc, N. & Crouch, J. A. Prokaryotic taxa play keystone roles in the soil Microbiome associated with Woody perennial plants in the genus Buxus. Ecol. Evol. 9, 11102–11111 (2019).

Nguyen, N. H. et al. FUNGuild: an open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 20, 241–248 (2016).

Kurzawińska, H., Mazur, S. & Nawrocki, J. Microorganisms colonizing the leaves, shoots and roots of Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens L). Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus. 18, 149–154 (2019).

Smedegaard-Petersen, V. Increased demand for respiratory energy of barley leaves reacting hypersensitively against Erysiphe graminis, Pyrenophora Teres and Pyrenophora Graminea. J. Phytopathol. 99, 54–62 (1980).

Boddy, L. & Hiscox, J. Fungal ecology: principles and mechanisms of colonization and competition by saprotrophic fungi. Microbiol Spectr 4:10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0019-2016 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0019-2016

Liu, F. et al. Correlation between the synthesis of Pullulan and melanin in Aureobasidium Pullulans. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 177, 252–260 (2021).

Mannaa, M. et al. Aureobasidium pullulans treatment mitigates drought stress in Abies Koreana via rhizosphere Microbiome modulation. Plants 12, 3653 (2023).

van Nieuwenhuijzen, E. J. & Aureobasidium Academic Press, Oxford,. in Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology (Second Edition) (eds. Batt, C. A. & Tortorello, M. L.) 105–109 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384730-0.00017-3

Wang, M. & Cernava, T. Overhauling the assessment of agrochemical-driven interferences with microbial communities for improved global ecosystem integrity. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 4, 100061 (2020).

Arnault, G., Mony, C. & Vandenkoornhuyse, P. Plant microbiota dysbiosis and the Anna karenina principle. Trends Plant. Sci. 28, 18–30 (2022).

Berg, G. et al. Plant microbial diversity is suggested as the key to future biocontrol and health trends. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol 93:5, fix050 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fix050

Runge, P., Ventura, F., Kemen, E. & Stam, R. Distinct phyllosphere Microbiome of wild tomato species in central Peru upon dysbiosis. Microb. Ecol. 85, 168–183 (2023).

Lichiheb, N. et al. Measuring leaf penetration and volatilization of Chlorothalonil and Epoxiconazole applied on wheat leaves in a laboratory-scale experiment. J. Environ. Qual. 44, 1782–1790 (2015).

Pinto, C. et al. Unravelling the diversity of grapevine Microbiome. PLOS ONE. 9, e85622 (2014).

Sumbula, V., Kurian, P. S., Girija, D. & Cherian, K. A. Impact of foliar application of fungicides on tomato leaf fungal community structure revealed by metagenomic analysis. Folia Microbiol. 67, 103–108 (2022).

Sieber, T. N. Chapter 6 - The phyllosphere mycobiome of woody plants. in Forest Microbiology (eds. Asiegbu, F. O. & Kovalchuk, A.) 111–132Academic Press, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822542-4.00003-6

Santra, H. K. & Banerjee, D. Fungal endophytes: A source for biological control agents. in Agriculturally Important Fungi for Sustainable Agriculture: Volume 2: Functional Annotation for Crop Protection (eds Yadav, A. N., Mishra, S., Kour, D., Yadav, N. & Kumar, A.) 181–216 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48474-3_6. (2020).

McNab, E. & Hsiang, T. Naturally occurring propiconazole-tolerant fungal isolates in the phyllosphere of Agrostis stolonifera. J. Plant. Dis. Prot. 131, 1195–1201 (2024).

Baćmaga, M., Wyszkowska, J. & Kucharski, J. The influence of Chlorothalonil on the activity of soil microorganisms and enzymes. Ecotoxicology 27, 1188–1202 (2018).

Sjokvist, E. et al. Dissection of Ramularia leaf spot disease by integrated analysis of barley and Ramularia collo-cygni transcriptome responses. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 32, 176–193 (2019).

Thach, T., Munk, L., Hansen, A. L. & Jørgensen, L. N. Disease variation and chemical control of Ramularia leaf spot in sugar beet. Crop Prot. 51, 68–76 (2013).

Cairney, J. W. G. Basidiomycete mycelia in forest soils: dimensions, dynamics and roles in nutrient distribution. Mycol. Res. 109, 7–20 (2005).

Tripathi, M. & Joshi, Y. What are lichenized fungi? in Endolichenic Fungi: Present and Future Trends (eds Tripathi, M. & Joshi, Y.) 1–26 (Springer, Singapore, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7268-1_1. (2019).

Yan, Z., Xiong, C., Liu, H. & Singh, B. K. Sustainable agricultural practices contribute significantly to one health. J. Sustain. Agr Environ. 1, 165–176 (2022).

Saunders, R., Saunders, T., Saunders, B. & Saunders, J. Boxwood Guide (Saunders Brothers, 2018).

Avenot, H. F., King, C., Edwards, T. P., Baudoin, A. & Hong, C. X. Effects of inoculum dose, temperature, cultivar, and interrupted leaf wetness period on infection of Boxwood by Calonectria pseudonaviculata. Plant. Dis. 101, 866–873 (2017).

Avenot, H. F., Baudoin, A. & Hong, C. Conidial production and viability of Calonectria pseudonaviculata on infected Boxwood leaves as affected by temperature, wetness, and dryness periods. Plant. Pathol. 71, 696–701 (2022).

Gehesquière, B. Cylindrocladium buxicola nom. cons. prop. (syn. Calonectria pseudonaviculata) on Buxus: molecular characterization, epidemiology, host resistance and fungicide controlGhent University, Belgium,. (2014).

Li, X. et al. Characterization of Boxwood shoot bacterial communities and potential impact from fungicide treatments. Microbiol. Spectr. 0, e04163–e04122 (2023).

Martin, K. J. & Rygiewicz, P. T. Fungal-specific PCR primers developed for analysis of the ITS region of environmental DNA extracts. BMC Microbiol. 5, 28 (2005).

Li, X. NanoPrep. https://github.com/xpli2020/NanoPrep. Accessed July 1. (2024).

Cuscó, A., Catozzi, C., Viñes, J., Sanchez, A. & Francino, O. Microbiota profiling with long amplicons using Nanopore sequencing: full-length 16S rRNA gene and the 16S-ITS-23S of the rrn operon. F1000Rsearch vol. 7 1755 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.16817.2 (2019).

Abarenkov, K. et al. Full UNITE + INSD dataset for Fungi. UNITE Community. https://doi.org/10.15156/BIO/1281531 (2021).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. P. Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis. ISME J. 11, 2639–2643 (2017).

Lahti, L. & Shetty, S. Tools for Microbiome analysis in R. (2017). http://microbiome.github.com/microbiome

Dunn, O. J. Multiple comparisons among means. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 56, 52–64 (1961).

Liu, C., Cui, Y., Li, X. & Yao, M. Microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 97, fiaa255 (2021).

Jaccard, P. The distribution of the flora in the alpine zone. New. Phytol. 11, 37–50 (1912).

Legendre, P. & Gallagher, E. D. Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia 129, 271–280 (2001).

Legendre, P. & Borcard, D. Box–Cox-chord transformations for community composition data prior to beta diversity analysis. Ecography 41, 1820–1824 (2018).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of Microbiome census data. PLOS ONE. 8, e61217 (2013).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community ecology package. https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan (2019).

Bray, J. R. & Curtis, J. T. An ordination of the upland forest communities of Southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 27, 325–349 (1957).

Mallick, H. et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLOS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009442 (2021).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodoll). 57, 289–300 (1995).

Martin, V. M. et al. Longitudinal disease-associated gut Microbiome differences in infants with food protein-induced allergic Proctocolitis. Microbiome 10, 154 (2022).

Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32, 2847–2849 (2016).

Peschel, S., Müller, C. L., von Mutius, E., Boulesteix, A. L. & Depner, M. NetCoMi: network construction and comparison for Microbiome data in R. Brief. Bioinform. 22, bbaa290 (2021).

Yoon, G., Gaynanova, I. & Müller, C. L. Microbial networks in SPRING - Semi-parametric Rank-Based correlation and partial correlation Estimation for quantitative Microbiome data. Front Genet 10:516 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.00516

Csardi, G. & Tamas nepusz. The Igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal, Complex Systems, 1695 (2006).

Jaccard, P. Nouvelles recherches Sur La distribution Florale. (1908). https://doi.org/10.5169/SEALS-268384

Hubert, L. & Arabie, P. Comparing partitions. J. Classif. 2, 193–218 (1985).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. On the adaptive control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing with independent statistics. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 25, 60–83 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI), project award no. 2020-51181-32135, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy. The authors would like to thank the grower for providing the study field and boxwood plants and Syngenta for supplying the three fungicides used in this study. We appreciated Robert Holtz of Virginia Tech for the field assistance and Dr. Margery L. Daughtrey, Claire Carter, and Clay Yokom for reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA-NIFA), under award number 2020-51181-32135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XL, PK, and CH conceptualization this study. OO, XL, PK and FG designed the experiments and examined the methodology. CT scouted and selected the research site. XL, OO, GH, HT, and AT collected the samples. XL performed the investigation and conducted formal bioinformatics and statistical analyses as well as data curation and drafted the manuscript. XL, PK, and CH conducted data visualization, validation, and interpretation. CH secured the funding, supervised the project, and provided resources. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscripts, as well as approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Hemmings, G., Omolehin, O. et al. Mycobiome of low maintenance iconic landscape plant boxwood under repeated treatments of contact and systemic fungicides. Sci Rep 15, 30150 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07593-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07593-3