Abstract

Channel modeling plays a pivotal role in the field of communications, particularly in the optical communication networks of backbone communication systems. Recent studies on optical channel modeling have utilized real-valued neural network (RVNN) to extract channel characteristics, an approach that does not fully account for the properties of complex-valued signals. To address this limitation, we propose a complex-valued conditional generative adversarial network (C-CGAN) in this paper to comprehensively learn channel features. We describe the architecture and parameters of the C-CGAN and employ complex-valued windowed construction for input data. Subsequently, we evaluate the model’s accuracy and generalization capabilities using the normalized mean square error (NMSE) and benchmark it against the real-valued conditional generative adversarial network (R-CGAN). The results indicate that the C-CGAN achieves better generalization across various scenarios, including different dataset sizes, noise levels, and input feature complexities, while also exhibiting a more stable training process. The NMSE achieved by the C-CGAN remains below \(2\times 10^{-2}\) and outperforms the R-CGAN. Additionally, analysis from the perspective of floating-point operations (FLOPs) reveals that the computational complexity of the C-CGAN is relatively low. To further validate scalability, we introduce a self-loop cascading mechanism that, under constrained training datasets, improves NMSE performance by 22.48% compared to the R-CGAN.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optical communication serves as the primary medium for information transmission in modern society, playing a crucial role in supporting the rapid growth of internet data1. As the foundation for achieving efficient and reliable data transmission, optical communication channels cover a wide range of applications, from home broadband access to global internet backbones, and are particularly indispensable in the interconnection of large data centers2. Deepening the research on optical fiber modeling can help reduce the costs of actual engineering projects and enhance the scientific community’s understanding of factors such as fiber dispersion, fiber nonlinearity, and optical amplifier noise3. Therefore, in the design of optical communication systems, optical channel modeling has garnered increasing attention and has become an essential task. Researchers have developed various traditional methods, which can generally be categorized into two types. One type utilizes numerical solution methods, such as the split-step Fourier method, which divides the entire fiber into multiple small segments and performs multiple iterations within each segment for channel modeling. This method achieves excellent accuracy but at the cost of significant computational overhead4. The other type simplifies equations through mathematical approximations, such as first-order perturbation theory5 and the Gaussian noise (GN) model6. While these approximation methods improve computational efficiency, they sacrifice accuracy and often fail to provide the detailed information required in optical networks, thereby limiting their applicability. Therefore, achieving fast and accurate optical channel modeling while providing relevant signal waveform information remains a significant research challenge.

Artificial intelligence (AI), since its introduction in the twentieth century, has permeated various aspects of society over nearly a century. In the field of optical communication, methods derived from neural networks have played a significant role in optical device design7, optical imaging8, optical sensing9, and particularly in optical channel modeling. These methods have found increasingly widespread application as data science continues to advance. Compared to traditional methods, neural networks are data-driven, do not require precise mathematical formulations or modular modeling techniques, and do not need prior knowledge of the system. Even when analytical solutions for the channel are unattainable and it is challenging to analyze and model the composition and related information of individual components, neural networks can still effectively simulate optical channels10. When designing optical communication systems, neural networks, with their inherent gradient information, can address the issue of missing gradients in numerical solutions, enabling end-to-end optimization of the optical network11. In most methods that use neural networks for optical channel modeling, the common practice is to decompose complex-valued optical signals into discrete real-valued time-varying sequences, followed by the design of appropriate networks for modeling. Different networks with specific architectures are suited to different problems and excel in handling different types of data. For time-correlated sequences of optical signals, a prominent approach is to utilize recurrent neural network (RNN) type networks. In12, a bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) network was employed on a dataset of 213 on-off keying (OOK) and pulse amplitude modulation (PAM4) signals, achieving acceptable results. Reference13 used a simplified Transformer network, which enabled long-distance and highly robust optical channel modeling. In optical communication, the ability to respond quickly and generate diverse data is also a critical requirement. However, directly using neural networks to process time-correlated sequences often results in high computational complexity. To address this, a fast and versatile data generation method based on conditional generative adversarial network (CGAN) has been applied to optical channel modeling14. This method, through the design of conditional vectors, achieves high-precision, low-complexity modeling under long-distance, multi-span, and various random noise scenarios, and can be generalized to different transmission powers and modulation formats. However, these existing methods are based on real-valued neural networks, and the treatment of inherently complex-valued optical signals through simple decomposition inevitably reduces efficiency.

Complex-valued neural network (CVNN) have been proven to be more efficient than real-valued neural network (RVNN) across multiple domains. In the field of optical communication, CVNN have demonstrated superior performance in nonlinear equalization15 and channel prediction16 compared to RVNN. CVNN are the optimal models for processing signal-related information because they can directly handle the phase of the signal, which represents temporal progression or positional differences, as well as the amplitude, which corresponds to the energy or power of the signal17. This capability allows CVNN to more comprehensively extract signal information and reduce the degrees of freedom within the neural network. As a result, CVNN converge faster during training, exhibit better generalization, and demonstrate greater robustness to noise18,19.

To address the limitations of existing modeling methods, this paper introduces a C-CGAN for optical fiber channel modeling. The C-CGAN is capable of simulating various impairments in single-carrier transmission, including self-phase modulation (SPM), group velocity dispersion (GVD), higher-order dispersion, amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) noise, and additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN). The paper describes the architecture of the constructed CVNN, which consists of a complex-valued generator network (C-GNet) and a complex-valued discriminator network (C-DNet). A condition vector is designed according to the characteristics of the signal to guide the data generation process of the C-GNet. Appropriate network parameters are chosen to ensure the efficiency and performance of the CVNN. During training, sufficient data are used to avoid overfitting and mode collapse. The modeling quality of the C-CGAN is evaluated using the normalized mean squared error (NMSE) metric and compared with R-CGAN. To assess the accuracy and generalization capability of the C-CGAN, tests are conducted under various conditions, including different transmission powers, modulation formats, transmission rates, and distances. The paper also demonstrates that, compared to R-CGAN, the C-CGAN has lower computational complexity in terms of required computing resources. Additionally, a self-cascading method is validated, showing that the C-CGAN can extend from short-range to long-distance transmission modeling with limited training data. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of CVNN to optical channel modeling. In the field of neural network modeling, model complexity represents a critical consideration. While sophisticated models like Transformer can achieve excellent modeling performance, this study proposes a lightweight C-CGAN model to optimally balance complexity and modeling accuracy. The proposed model can adequately meet the precision requirements for optical communication system modeling while maintaining low complexity.

The organization of this article is as follows. Section II introduces the fiber simulation system and the modeling principle of the C-CGAN , briefly reviews the modeling principle of the SSFM, presents the structure and parameters of the C-CGAN, and constructs the training and testing datasets for neural network training. Section III introduces the training results of the network, sets different conditions to verify the generalization ability of the network, and discusses in detail the complexity of the network and the effect of the self-cascade method. Section IV summarizes the full text.

Principles

In this chapter, we primarily reviewed the Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation (NLSE), introduced the optical communication simulation system we constructed, and discussed the structure, parameters, and data used for the C-CGAN.

Fiber channel model

The propagation of optical pulses in single-mode fibers is governed by the NLSE20:

where U(z, t) represents the slowly varying envelope of the optical signal in the fiber, L represents the transmission distance, t represents the transmission time, \(\alpha\) represents the attenuation factor of the fiber channel, \(\beta _2\) represents the group velocity dispersion parameter, \(\beta _3\) represents the third-order dispersion parameter, and \(\gamma\) represents the nonlinear coefficient, respectively.

Since an analytical solution for the NLSE has not been found so far, the most widely used method is the SSFM to obtain numerical solutions for the equation21. The numerical solution of the equation can be expressed as:

where l is the simulation step length taken by the SSFM(split-step Fourier method), linear operator \(\hat{L} = -{\alpha }/{2} -j{\beta _2\partial ^2}/{2\partial z^2} + {\beta _3\partial ^3}/{6\partial z^3}\), nonlinear operator \(\hat{N}\left[ U(z,t)\right] = j\gamma |U(z,t)|^2\). Theoretically, the smaller the simulation step size, the more accurately the simulation can replicate the propagation of optical signals in the fiber. However, this can also lead to increased computational complexity. Due to the attenuation of optical signals in the fiber, each fiber segment requires compensation using an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (EDFA). While compensating for the signal attenuation, the EDFA introduces ASE noise, which degrades the quality of the optical signal.

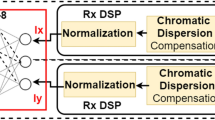

We have constructed a classical optical fiber communication system. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the transmitter section of this typical optical communication system comprises generating bit stream sequences, symbol mapping, quadruple up-sampling, root-raised cosine (RRC) filtering, setting transmission power, and defining the optical signal-to-noise ratio (OSNR). After modulation by continuous-wave (CW) lasers, the signal enters the optical fiber. At the receiver, the optical signal is converted into electrical signals via photodetection, and then undergoes digital back propagation (DBP) or dispersion compensation, RRC filtering, down-sampling, and demodulation to ultimately recover the transmitted data. We collect the transmitted data before the optical signal enters the fiber and the outgoing data after EDFA compensation at the fiber’s exit. This collected data is used as a training and testing dataset for the neural network. Some parameters of the optical fiber system depicted in Fig. 1 are listed in Table 1. We extracted the data required for the C-CGAN from the output of the transmitter and the input of the receiver in the system described in Fig. 1a. As shown in Fig. 1b, the collected data were normalized according to Eq. (3) and then used to construct the dataset.

where \(\hat{D_i}\) represents the normalized symbols, \(L_D\) is the symbol length, and \(D_i\) denotes the unnormalized symbols. This normalization not only reduces the risk of overfitting and accelerates the training of the neural network but also helps to decouple the correlation between power information22. For the C-CGAN model, normalization enables it to learn more generalized and transferable features, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization capability. It also reduces redundancy in the model parameters, making the C-CGAN more efficient and concise.

The pulse broadening caused by dispersive effects leads to ISI, which is exacerbated due to its coupling with nonlinear effects, thus degrading the quality of the data set. To alleviate these issues, the complex-valued conditioning vector must include temporally correlated symbols, ensuring that the neural network can learn relevant patterns. Due to the inherent stochasticity of C-CGAN, unstructured training can lead to a waste of computational resources. Therefore, constructing a carefully designed complex-valued conditioning vector to guide the C-CGAN in generating samples that closely match the target data distribution is essential. To effectively guide the generation process of the C-CGAN, we constructed a complex-valued conditional vector with temporal correlation. In this work, we utilized a fixed-length time-sliding window to create the dataset. To balance network complexity and the impact of intersymbol interference, we linked additional symbols to the left and right of each symbol. Specifically, we set the total number of connected symbols within each span \(m_1\) to 9, with 4 symbols on either side of the target symbol. Considering the 4-times upsampling at the transmitter, the complex-valued conditional vector encompassed 32 connected symbols, resulting in a vector dimension of 36. Unless otherwise stated, the default parameters listed in Table 1 were used throughout this paper.

Principles of C-CGAN

As shown in Fig. 2a,b, a basic complex-valued neuron is implemented using two real-valued neurons, with complex weights and biases. In forward propagation, unlike real-valued neurons, the input and output of complex-valued neurons are both complex data. In the complex domain, considering the mapping from one complex data point \(Z^{In}=(X^{In}_{R}, X^{In}_{I})\) to another complex data point \(Z^{Out}=(X^{Out}_{R}, X^{Out}_{I})\), we assume that the bias value is 0:

where \(W_{R1}= |W|\cos {\theta }\), \(W_{I1}= -|W|\sin {\theta }\), \(W_{R2}= |W|\sin {\theta }\), \(W_{I2}= |W|\cos {\theta }\), \(W= |W|\exp (j\theta )\) is the weight of the complex-valued neuron.

The learning process of neural networks is inherently uncertain, yielding various possible mappings. To better illustrate this process, as shown in Fig. 2c, we consider a very simple case. The green solid line in the figure represents the correct mapping relationship. For R-CGAN, due to the decomposition of complex numbers into two real numbers and the neglect of phase information, there can be a large number of invalid mappings, as indicated by the red dashed line in Fig. 2c. Training C-CGAN with complex data effectively utilizes phase information and amplitude variations, reducing many invalid mappings in practical applications and accelerating network convergence compared to R-CGAN, as shown by the purple dashed line in Fig. 2c.

As shown in Fig. 3, the C-CGAN architecture proposed in this work consists of a C-GNet and a C-DNet. The C-GNet, as depicted in Fig. 3a, is composed of 3 hidden layers and 1 output layer. The hidden layers contain 144, 128, and 32 complex-valued neurons, respectively, and the output layer has 4 complex-valued neurons. The C-DNet, shown in Fig. 3b, also has 3 hidden layers and 1 output layer. The hidden layers consist of 128, 128, and 32 complex-valued neurons, respectively, and the output layer has a single complex-valued neuron.

The design of activation and loss functions is critical to the performance of C-CGAN. Analogous to R-CGAN, in the C-CGAN architecture illustrated in Fig. 3, nonlinear transformations are realized through nonlinear activation functions. However, unlike the R-CGAN , the inputs and outputs of the C-CGAN are complex-valued, which necessitates the use of complex-valued activation functions for nonlinear transformations. Several complex-valued activation functions have been proposed in the literature, such as modReLU, \(\mathbb {C}\)ReLU, and zReLU23. Considering factors like gradient vanishing/explosion and convergence speed, we adopted the \(\mathbb {C}\)ReLU activation function for the complex-valued neurons within the C-CGAN network, as shown in Eq. (5). The \(\mathbb {C}\)ReLU activation function has demonstrated good performance in research areas such as channel estimation24 and channel equalization25, this is the first time it has been applied to channel modeling.

The choice of the loss function can significantly impact the training effect of the network. To mitigate the influence of speckle noise and outliers, this paper proposes using the mean squared error function separately on the real and imaginary parts of the complex numbers, constructing the complex mean squared error (CMSE) as the loss function for the neural network. The expression for CMSE is as follows:

where y is the real data, \(\hat{y}\) is the data generated by C-GNet, the N is the length of the data.

In the C-CGAN, the output after passing through the i-th hidden layer is expressed as shown in Eq. (7).

where \(N_{i}\) is the number of neurons in the i-th layer, \(W^{i}_{{j_{i-1}}{k_i}}\) represents the weights of the i-th layer, \(Z^{In}\) denotes the input complex-valued data.

As depicted in Fig. 3b, the output of the C-DNet represents the probability of a sample, corresponding to a binary classification task with values ranging from 0 to 1. To accommodate the complex-valued operations within the C-DNet, we employ a modified sigmoid function for calculating its output.

where \(|Z^{In} |\) is the absolute value of complex signal. To provide a comprehensive and clear illustration of the proposed C-CGAN model architecture, Table 2 details the key structural parameters of the network, including: input layer dimensions, number of neurons and dimensions in hidden layers, output layer dimensions, learning rate settings, activation function types, and optimizer selection. This explicit parameter description facilitates readers’ in-depth understanding of the model construction details.

In the complex-domain parameter optimization strategy of C-CGAN, the backpropagation algorithm adheres to mathematical principles analogous to those in real space, extended through holomorphic functions. The network employs gradient descent-based optimization algorithms to iteratively refine parameters after computing composite loss functions via forward propagation. This process propagates error signals backward through computational graphs to hidden layer neurons, calculating complex Jacobian matrices using chain differentiation rules. The weight matrix \(W^{l}\) and bias vector \(b^{l}\) are updated according to the following incremental rule:

where l denotes network depth and \(\eta\) represents the dynamic learning rate. Under an end-to-end supervised learning framework, C-CGAN achieves progressive optimization in complex parameter space by minimizing the Hilbert-Schmidt distance between model outputs and annotated data, ensuring precise alignment between spectral characteristics of generated samples and statistical distributions of target labels.

The performance of the C-CGAN is closely tied to the use of batch normalization, which is a critical component for optimizing neural networks. Although the batch normalization technique used in R-CGAN can be directly applied to the C-CGAN, it does not guarantee that the real and imaginary parts of the normalized complex-valued data have the same variance. To address this issue, we have adopted a complex-valued batch normalization (\(\mathbb {C}\)BN) method26 specifically designed to handle complex-valued data. When applying \(\mathbb {C}\)BN to the C-CGAN, it ensures that both the real and imaginary parts of the complex-valued data have the same variance after the normalization process. This helps the C-CGAN to better handle the complex-valued nature of the data. Additionally, the initialization of the network parameters plays a crucial role in optimizing the C-CGAN. Proper parameter initialization can help maintain a reasonable distribution and scale of the activation values during forward propagation and the gradients during backward propagation, accelerating the training process and reducing instability issues. Due to the unique characteristics of complex-valued weights, which contain both phase and magnitude information, and the use of the \(\mathbb {C}\)ReLU activation function in the C-CGAN, we have adopted a specialized initialization method known as Kaiming initialization27. This method is applied separately to the real and imaginary parts of the complex-valued weights, further enhancing the convergence of the C-CGAN. The biases in the C-CGAN are initialized to 0. To ensure the correct generation of symbols and effectively capture the input-output mapping relationship, the dimension of the noise vector must be greater than the dimension of the mapped output. In this work, we have set the noise vector dimension to 5. The batch size used in the training of the C-CGAN is set to 1000. For the learning rate selection in C-CGAN, compared with real-valued networks, the simultaneous optimization of both magnitude and phase in the complex domain makes the learning rate setting more challenging. Recent studies have shown that an excessively high learning rate may cause oscillatory or divergent behavior in the complex plane during optimization, particularly when the phase variation of complex gradients is significant, which amplifies the inconsistency in parameter update directions. Conversely, an overly low learning rate substantially slows down convergence and increases the risk of being trapped in local minima28. Through systematic simulations, this work identifies \(1\times 10^{-3}\) as the optimal learning rate for C-CGAN. Regarding the optimizer selection, SGD, RMSprop, and Adam are three commonly used optimization algorithms. Specifically, SGD tends to exhibit oscillations or divergence when dealing with abrupt phase variations in complex-valued gradients, making it ineffective in addressing local optima in the complex plane. Although RMSprop improves stability through adaptive learning rate adjustment, its decay factor requires careful tuning for phase-sensitive tasks, resulting in a complicated hyperparameter optimization process. In contrast, the Adam optimizer combines momentum mechanisms with adaptive learning rate strategies, enabling dynamic adjustment of the distribution characteristics for both real and imaginary parts of complex gradients29. Therefore, Adam is selected as the optimizer for C-CGAN in this work to achieve more stable and efficient training.

C-CGAN channel model

C-GNet receives two inputs: a complex-valued condition vector constructed from optical fiber data, and a noise vector that follows a Gaussian random distribution. C-GNet utilizes these inputs to generate data with characteristics of a genuine signal. The generated data, along with the real data and the complex-valued condition vector, are concatenated and fed into C-DNet. C-DNet is trained to distinguish between the generated data and real data, effectively evaluating the authenticity of the data. Through this training process, the C-GNet learns to capture the underlying transmission characteristics of the optical fiber channel, generating data that the C-DNet cannot reliably distinguish from real data. This completes the training of the entire C-CGAN model. Once the C-CGAN is trained, the resulting neural network model can be employed to replace the optical fiber and amplifier components shown in Fig. 1a, thereby effectively simulating the propagation of optical signals in the fiber channel.

This paper selects NMSE as the measurement standard, and the expression of NMSE is30:

where \(\Vert \cdot \Vert _2\) represents the L2 norm. When the NMSE value of the neural network is less than \(2\times 10^{-2}\), we consider the accuracy of the neural network modeling to be acceptable. The smaller the NMSE value, the better the modeling results.

Results and discussion

To avoid mode collapse in the C-CGAN, the training data used for transmission distances ranging from 1 Span to 8 Spans is on the order of \(8\times 10^5\) data points. For transmission distances exceeding 9 Spans, the training data used is on the order of \(3\times 10^6\) data points. To minimize randomness, the C-CGAN channel model method and other methods employ identical algorithms at both the transmitting and receiving terminals.

C-CGAN modeling capability

To demonstrate the learning capability of the C-CGAN , we first conducted comparisons with the SSFM under multiple metrics and identical conditions. Using a transmission power of 10 dBm and a transmission distance of 1 span to simulate channel conditions, we applied both the SSFM and C-CGAN methods. Under these conditions, the resulting modeling NMSE value was \(6.01\times 10^{-4}\), which is far below the acceptable threshold of \(2\times 10^{-2}\). Figure 4a,b display the signal constellation diagrams of the SSFM and C-CGAN methods, respectively, after compensation by an EDFA. Figure 4c,d show the constellation diagrams of the SSFM and C-CGAN methods, respectively, following dispersion compensation (CDC). From these figures, it can be observed that the optical signals are affected by nonlinear effects, leading to phase rotation after CDC, with stronger nonlinear effects experienced by signals of greater amplitude. Figure 4e,f display the constellation diagrams of the SSFM and C-CGAN methods, respectively, after compensation by digital back propagation (DBP). It can be observed that DBP is capable of compensating for the nonlinear effects experienced by the signals. Figure 4a–f visually demonstrate that the C-CGAN network has learned the distribution pattern in the single-carrier optical fiber channel, successfully fitting the dispersion effect, nonlinear effect, and noise caused by EDFA in the optical fiber, and achieving results comparable to those obtained using the SSFM method.

The SSFM method and the C-CGAN method were used to produce the fiber optic constellation diagram, the CDC constellation diagram and the DBP compensation constellation diagram. (a) SSFM after optical fiber, (b) C-CGAN after optical fiber, (c) SSFM after CDC, (d) C-CGAN after CDC, (e) SSFM after DBP, (f) C-CGAN after DBP.

Comparison of SSFM and C-CGAN methods in time and frequency domains. (a) Time-domain signal of SSFM, (b) zoomed-in comparison of time-domain signals, (c) time-domain signal of C-CGAN, (d) frequency-domain signal of SSFM, (e) zoomed-in comparison of frequency-domain signals, (f) frequency-domain signal of C-CGAN.

In addition to the intuitive comparison through constellation diagrams, we also compared signals in the time-frequency domain to further validate the model’s accuracy from different perspectives. Figure 5a–f show the time-frequency domain modeling results of the optical channel with a transmission power of 0 dBm and a transmission distance of 4 spans. Under these conditions, the NMSE of the C-CGAN model is \(7.65\times 10^{-4}\), which is far below the acceptable threshold of \(2\times 10^{-2}\). In the time domain, as shown in Fig. 5a–c, we obtained time-domain plots using both the SSFM and the C-CGAN methods, over a time range of 0–18,000 ps. To further highlight the differences between these two approaches, we narrowed the time range to 9800–10,000 ps and plotted the results on the same graph, as depicted in Fig. 5b. The red curve represents the SSFM method, while the purple dashed line represents the C-CGAN method. Figure 5a–c demonstrate that the C-CGAN modeling achieves comparable precision to the SSFM method within the time domain. We also utilized the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to convert the signal from the time domain to the frequency domain, with the results presented in Fig. 5d–f. Figure 5d,f show the frequency-domain plots obtained using the SSFM method and the C-CGAN method, respectively. Similarly, we performed a zoom-in within the frequency domain and plotted the results on the same graph, as shown in Fig. 5e. The C-CGAN method achieved modeling results in the frequency domain that are nearly identical to those of the SSFM method. Overall, the results in Fig. 5 demonstrate that the proposed C-CGAN method achieves high accuracy in both the time and frequency domains compared to the SSFM method.

Similarly, the C-CGAN approach has achieved excellent results under various transmission distances and launch power conditions. In this work, the NMSE is used to evaluate the modeling performance of the C-CGAN. As shown in Fig. 6, the NMSE values are presented for different transmission distances under launch power conditions of \(-2\) dBm, 0 dBm, and 2 dBm. In the case of short-distance transmission over 1 span, the NMSE values were \(3.58\times 10^{-4}\) at \(-2\) dBm, \(3.41\times 10^{-4}\) at 0 dBm, and \(3.90\times 10^{-4}\) at 2 dBm. For long-distance transmission over 15 spans, the NMSE values were \(9.97\times 10^{-3}\) at \(-2\) dBm, \(9.83\times 10^{-3}\) at 0 dBm, and \(1.04\times 10^{-2}\) at 2 dBm. Theoretically, when the transmission distance is fixed, an increase in signal power leads to enhanced nonlinear effects. Additionally, the coupling of dispersion and nonlinearity makes the distribution of optical signal propagation more challenging to learn. An increase in power also results in greater ASE noise generated by the EDFA, further degrading signal quality. When the power is fixed, an increase in transmission distance exacerbates various impairments to the signal, making it more difficult to model. Despite these challenges, Fig. 6 shows that even over 15 spans, the C-CGAN achieves NMSE values well below the acceptable threshold of \(2\times 10^{-2}\). These results indicate that the C-CGAN method possesses robust modeling capabilities, effectively capturing complex nonlinear and dispersive effects under different power and distance conditions.

Generally speaking, CVNN achieve better results than RVNN because they can fully utilize the phase and magnitude information of complex-valued data. In this work, we set up an R-CGAN with the same number of neuron nodes as the complex-valued neural network and trained it using the same data. The learning rate, optimizer, and batch size for the real-valued neural network were kept consistent with those of the complex-valued neural network. The loss function was chosen to be MSE, and the nonlinear activation function was selected to be ReLU. The construction of the real-valued neural network data was based on the complex-valued neural network, where each complex-valued data point was sequentially split into two real-valued data points. Unlike the C-CGAN, the dimension of the environment vector in the R-CGAN was set to 11, corresponding to the total number of encoded symbols m2. The results are shown in Fig. 7.

Under transmission power conditions of 0 dBm, the C-CGAN demonstrated faster convergence speed and higher stability during training compared to the R-CGAN, at both 1 span and 15 spans of transmission distance. In the R-CGAN, significant fluctuations in NMSE values were observed throughout the training process, and the achieved NMSE values were higher than those of the C-CGAN, which aligns with theoretical expectations. As shown in Fig. 7, both the C-CGAN and R-CGAN converge after approximately 40 training epochs. Under 1 span condition, the R-CGAN achieved an NMSE of \(3.70\times 10^{-4}\) at convergence, whereas the C-CGAN’s NMSE was 7.9% lower than that of the R-CGAN. For the transmission distance of 15 spans, the R-CGAN achieved an NMSE of \(1.03\times 10^{-2}\) at convergence, while the C-CGAN’s NMSE was approximately 5.3% lower than that of the R-CGAN. The superior performance of the C-CGAN can be attributed to its ability to utilize both the amplitude and phase information of complex-valued data, whereas the R-CGAN can only make use of amplitude information, allowing the C-CGAN to achieve better modeling performance.

Research on network generalization ability

The generalization capability of a neural network is a crucial measure of its practical value. To evaluate the generalization capability of the neural network, we tested the trained model using data that was not utilized during the training process. Performance was still assessed using the NMSE metric.

During the training phase of the neural network, the training dataset has a fixed power level. To study the network model’s generalization capability with respect to signal power, neural network models trained under conditions of transmit powers of \(-2\) dBm, 0 dBm, and 2 dBm were used, and the generalization ability was verified by changing the input signal power. Specifically, for the trained network models, the input signal power was varied in steps of 0.5 dBm, covering a total range of \(\pm 2\) dBm around the training power conditions. The generalization capabilities of these three different models for a single-span transmission scenario were evaluated, and the results are presented in Fig. 8.

As shown in Fig. 8, when using the C-CGAN model in 1 span, both increasing and decreasing the input signal power lead to an increase in the NMSE value. Although the signals are normalized, which theoretically should mitigate the impact of signal power on model performance, the presence of nonlinearities, dispersion, and ASE noise introduces power-related stochastic disturbances into the dataset, resulting in reduced accuracy when the model is applied at power levels different from those during training. Comparing the R-CGAN with the C-CGAN, it can be observed that the C-CGAN model exhibits stronger generalization capabilities against variations in input signal power across different power conditions. Moreover, as the power range increases, the error accumulation of the C-CGAN remains lower than that of the R-CGAN. Specifically, when using the model trained at 2 dBm, at a high power of 4 dBm, the NMSE of the C-CGAN is 81.45% of the R-CGAN’s value, and when using the model trained at \(-2\) dBm, at a low power of \(-4\) dBm, the NMSE of the C-CGAN is 87.02% of the R-CGAN’s value. Overall, the C-CGAN model demonstrates better generalization capability with respect to variations in input signal power compared to the R-CGAN model. Despite their sensitivity to power changes, the NMSE values obtained by both models remain well below the acceptable threshold of \(2\times 10^{-2}\), indicating their effectiveness in simulating fiber-optic transmission characteristics.

In this study, the training signals we selected were all in 16 quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) format. However, in actual communication systems, signals are typically transmitted using various modulation formats such as quadrature phase shift keying (QPSK), 32QAM, and 64QAM. To evaluate the generalization capability of the C-CGAN model for these different modulation formats, we chose QPSK, 32QAM, and 64QAM modulated signals with a launch power of 10 dBm under single-span conditions. We utilized the 16QAM model trained under 10 dBm launch power and single-span conditions.

The data from the output of the fiber was compensated using the DBP algorithm. Fig. 9a,c,e show the constellation diagrams obtained using the SSFM after DBP compensation, while Fig. 9b,d,f show the constellation diagrams obtained using the C-CGAN method after DBP compensation. At the launch power of 10 dBm, the NMSE for the QPSK, 32QAM, and 64QAM modulation formats using the C-CGAN method were \(1.20\times 10^{-3}\), \(9.66\times 10^{-4}\), and \(9.45\times 10^{-4}\), respectively, which are all significantly lower than the acceptable threshold of \(2\times 10^{-2}\). In comparison, the NMSE for the R-CGAN method were \(1.36\times 10^{-3}\), \(1.05\times 10^{-3}\), and \(9.86\times 10^{-4}\), respectively. These results demonstrate the superior generalization capability of the C-CGAN model to different modulation formats, as its performance is better than the R-CGAN model across the various modulation schemes evaluated.

In all the network training conducted so far, the symbol rate of the optical fiber transmission system was set to 30 Gbaud. To study the impact of different symbol rates on the generalization capability of the C-CGAN, this work investigates the performance at symbol rates of 20 Gbaud, 40 Gbaud, 50 Gbaud, and 60 Gbaud. For this purpose, we utilize the model that was trained using the 16QAM, 30 Gbaud signal data as the optical fiber channel.

At a transmission distance of 1 span, the NMSE values obtained by the C-CGAN were \(8.28\times 10^{-4}\) at 20 GBaud, \(1.67\times 10^{-3}\) at 40 GBaud, \(7.23\times 10^{-3}\) at 50 GBaud, and \(1.88\times 10^{-2}\) at 60 GBaud. For the R-CGAN model, the NMSE values were \(9.23\times 10^{-4}\) at 20 GBaud, \(1.84\times 10^{-3}\) at 40 GBaud, \(7.79\times 10^{-3}\) at 50 GBaud, and \(2.1\times 10^{-2}\) at 60 GBaud. At the lower symbol rate of 20 GBaud, the NMSE of the C-CGAN was 10.24% lower than the R-CGAN model. At the higher symbol rate of 60 GBaud, the NMSE of the C-CGAN was 10.31% lower than the R-CGAN model. As shown in Fig. 10, the NMSE values increased as the symbol rate was increased. Particularly at the higher symbol rates, the impact of dispersion broadening made the situation more complex, causing the NMSE to increase significantly. Indeed, the NMSE of the R-CGAN model exceeded the acceptable threshold of \(2\times 10^{-2}\) at 60 GBaud. However, even at the increased symbol rates, the NMSE obtained with the proposed C-CGAN model remained below the acceptable threshold of \(2\times 10^{-2}\) and were lower than the R-CGAN model.

Within a single span, intervals of 1 km were used, and the data employed had never appeared in the neural network’s training. This work selected launch powers of \(-2\) dBm, 0 dBm, and 2 dBm as examples. Fig. 11 displays the NMSE at different distance offsets. The x-axis values are calculated using the formula \(\triangle {L}=L_{Span}-L_{Span}^{\prime }\), where \(L_{Span}\) represents the distance of one span at 75 km, and \(L_{Span}^{\prime }\) denotes the signal transmission distance at the data collection point. The y-axis shows the NMSE values.

As can be seen, altering the transmission distance over one Span significantly impacts the model’s accuracy. Theoretically, varying transmission distances lead to changes in the extent of dispersion and nonlinear effects experienced by the signal, thus degrading the performance of a model trained for a specific distance. Under the high-power condition of 2 dBm, when the transmission distance over one Span is 80 km, the NMSE of the C-CGAN model is \(1.80\times 10^{-2}\), while the NMSE of the R-CGAN model is \(1.98\times 10^{-2}\), representing a 9.09% reduction for the C-CGAN model compared to the R-CGAN model. Under the low-power condition of \(-2\) dBm, when the transmission distance over one Span is 70 km, the NMSE of the C-CGAN model is \(1.42\times 10^{-2}\), while the NMSE of the R-CGAN model is \(1.64\times 10^{-2}\), indicating a 13.05% reduction for the C-CGAN model compared to the R-CGAN model. For distance differences within the range of -5 km to 5 km, the NMSE of the proposed C-CGAN model remains below the maximum acceptable threshold of \(2\times 10^{-2}\) and is consistently lower than that of the R-CGAN model, demonstrating the robustness of the proposed model to distance variations.

In this study, we employed simulation data generated by solving the NLSE using the SSFM to model optical fiber signal transmission. To validate the effectiveness of the C-CGAN approach, we established an experimental platform and collected measured data, with the detailed system architecture shown in Fig. 12. At the transmitter, an external cavity laser (ECL) operating at 1550 nm with a linewidth of 100 kHz was utilized as the optical source. A 12 GBaud baseband signal was generated by an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG) at 25 GSa/s and modulated via an IQ modulator. The modulated signal was then processed by a polarization multiplexing module, which consisted of a polarization-maintaining optical coupler (PM-OC), a polarization controller (PC), and a polarization beam combiner (PBC). The optical signal was subsequently amplified by an EDFA, with its launch power precisely controlled using a variable optical attenuator (VOA).

Actual optical fiber communication system. AWG: arbitrary waveform generator. ECL: external cavity laser. PDM: polarization division multiplex. PM-OC: polarization-maintaining optical coupler. PC: polarization controller. PBC: polarization beam combiner. EDFA: erbium-doped fiber amplifier. VOA: variable optical attenuator. SSMF: standard single-mode fiber. LO: local oscillator. PBS: polarization beam splitter. BPD: balanced photonic detector. DPO: digital phosphor oscilloscope. OBPF: optical bandpass filter.

The transmission link comprised 15 spans of 75 km standard single-mode fiber. At the receiver, a homodyne coherent detection scheme was employed, incorporating a local oscillator (LO), polarization beam splitter (PBS), and balanced photodetectors (BPDs) to decompose the received optical signal into four orthogonal components. These signals were captured and digitized by a digital phosphor oscilloscope (DPO) operating at 100 GSa/s, followed by signal recovery and demodulation through digital signal processing (DSP).

Following the data processing methodology described in Section Principles, we preprocessed the acquired experimental signal data before feeding it into the network for training. Specifically, we completed model training using the dataset obtained at 0 dBm power condition. Subsequently, a systematic evaluation was conducted to assess the generalization capabilities of both C-CGAN and R-CGAN models, with experimental results illustrated in Fig. 13.

The experimental results demonstrate that under 15-span transmission conditions with an input power of \(-1\) dBm, the C-CGAN model maintains modeling accuracy at the order of \(1\times 10^{-2}\) in terms of the minimum NMSE, while the R-CGAN model only achieves \(1.80\times 10^{-2}\) under identical conditions. Whether in low-power or high-power operating regimes, the modeling performance of R-CGAN is significantly inferior to that of C-CGAN. These comprehensive experimental results conclusively validate the effectiveness and superiority of the C-CGAN method in practical optical fiber communication systems.

Computational complexity

To evaluate the computational complexity, we opt to use FLOPs as our metric. In the ensuing complexity analysis, we will disregard the contributions from addition operations and focus solely on the FLOPs generated by multiplications. For the R-CGAN model, without accounting for the FLOPs associated with the fully connected layers including biases, the FLOPs can be calculated as follows:

where N denotes the length of the data used, \(RNeu_{1}\) represents the input data dimension, which satisfies \(RNeu_{1}=80 \times span_N + RZ_{size} + 8\), where \(span_N\) is the number of Span crossings, and \(RZ_{size}\) is the dimension of the noise data. \(RNeu_{2}\) to \(RNeu_{5}\) represent the number of neurons from the first hidden layer to the output layer.

Since one complex number multiplication operation involves four real number multiplications, the FLOPs for the C-CGAN model can be calculated as:

where \(CNeu_{1}\) is the input data dimension satisfying \(CNeu_{1}=32 \times span_N + CZ_{size} + 4\), \(CZ_{size}\) is the noise data dimension. From \(CNeu_{2}\) to \(CNeu_{5}\) are the number of neurons from the first layer to the output layer.

From the expression of FLOPs, it can be observed that when using the C-CGAN for fiber channel modeling, the computational complexity is independent of the signal transmit power and fiber parameters, and depends solely on the volume of data and the transmission distance.

Figure 14a illustrates the changes in complexity and NMSE with respect to the transmission distance. When the transmission distance is 1 Span, the FLOPs required for the C-CGAN model are \(7.48\times 10^9\), whereas for the R-CGAN model, they are \(7.79\times 10^9\), representing a 3.88% reduction for C-CGAN compared to R-CGAN. When the transmission distance is 15 Spans, the FLOPs required for C-CGAN are \(2.44\times 10^{10}\), whereas for R-CGAN, they are \(2.89\times 10^{10}\), indicating a 15.66% reduction for C-CGAN compared to R-CGAN. From Fig. 14a, it can be observed that as the transmission distance increases, the complexity advantage of C-CGAN over R-CGAN becomes more pronounced. Additionally, in terms of NMSE values, C-CGAN outperforms R-CGAN at all distances. Under the simulation condition of 15-span and \(2^{18}\) data magnitude, a rigorous training efficiency comparison was conducted on identical hardware (CPU: 13th Gen Intel® \(\text {Core}^{\textrm{TM}}\) i9-13900KF, GPU: NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 Ti). The experimental results demonstrate that the C-CGAN model achieves a training time of only 28.87 s, representing a statistically significant 21.3% reduction compared to the R-CGAN model’s 36.68 s. This quantitative evidence not only visually confirms the low-complexity characteristic of the C-CGAN approach but also substantiates its practical value in optical fiber channel modeling from a computational efficiency perspective.

Figure 14b shows the comparison of data volume against FLOPs. We selected 15 different data volumes for the 15 Span transmission distance. When the data volume is \(2^{25}\), the FLOPs required for the C-CGAN model are 3.12\(\times 10^{12}\), while for the R-CGAN model, they are \(3.70 \times 10^{12}\), representing a 15.67% reduction for C-CGAN compared to R-CGAN. As the data volume increases, the advantage of C-CGAN over R-CGAN becomes increasingly pronounced.

Self circulating cascade

Typically, the approach for neural network modeling involves collecting data and training the model under a specific transmission distance condition. However, due to practical constraints, there may be situations where the available data is limited. For instance, sometimes only data for a 1-Span transmission distance is available, yet simulations are required for 2 Spans or higher transmission distances. To address this issue, this work proposes a recursive cascading method. The self-cascading method employs an iterative prediction approach using a single-span trained model. Specifically, the initial data is fed into the model to obtain the output, which is then reconstructed as the input for the next iteration. This process repeats cyclically until the target number of spans is achieved. This approach eliminates the need to train multiple cascaded models, enabling multi-span modeling with just a single-span trained neural network, thereby substantially reducing the training time. The authors utilize the model trained under the 1-Span condition and apply a multi-level recursive cascading approach to simulate fiber channel transmission for 2 Spans and higher transmission distances. This enables them to obtain NMSE values for these different transmission conditions. The NMSE values derived from this recursive cascading approach are then compared with the NMSE values predicted by models trained directly on the corresponding transmission distance data.

Using the recursive cascading method, the C-CGAN model achieved a NMSE of \(9.83\times 10^{-3}\) when directly trained on data with a transmission distance of 15 Spans and a launch power of 0 dBm. When using the 1-Span model and applying the recursive cascading approach, the NMSE was \(1.62\times 10^{-2}\). For the R-CGAN model, direct training on 15-Span, 0 dBm data resulted in an NMSE of \(1.03\times 10^{-2}\). However, using the 1-Span model and the recursive cascading method, the NMSE increased to \(2.09\times 10^{-2}\), exceeding the acceptable threshold of \(2\times 10^{-2}\). Compared to the R-CGAN model, the C-CGAN model showed a 22.48% improvement in NMSE for the 15-Span transmission condition. Additionally, as observed in Fig. 15, the error accumulation increases with higher cascading transmission distances, but the C-CGAN model using the recursive cascading approach maintains lower errors than the R-CGAN model. Compared to modeling and prediction under specific transmission distances, the recursive cascading modeling approach reduces the dependence on data and makes fiber channel modeling more accessible. This method effectively addresses the limitations posed by limited data availability, particularly when attempting to simulate higher transmission distances using data collected from shorter distances. By leveraging the capabilities of the C-CGAN network, the recursive cascading approach can accurately model fiber channels at different transmission distances, even in the face of data constraints. This flexibility and adaptability make it a valuable tool for practical fiber modeling scenarios.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a modeling approach based on a complex-valued neural network, utilizing the C-CGAN to fit the fiber channel. We investigated the NMSE performance of C-CGAN under multiple Span conditions and achieved results significantly lower than the acceptable threshold of \(2\times 10^{-2}\). Compared to the R-CGAN under the same conditions, the C-CGAN achieved lower NMSE and faster convergence speed. We also conducted comprehensive comparisons in terms of constellation diagrams and time-domain waveforms, which yielded consistent results.

Generalization capability is one of the key metrics for the C-CGAN network. We studied the NMSE impact of C-CGAN and R-CGAN under different optical signal powers, modulation formats, symbol rates, and transmission distances, and all results were below \(2\times 10^{-2}\), demonstrating the effectiveness of C-CGAN and achieving satisfactory performance. The comparison of complexity with R-CGAN also proved the advantage in terms of computational time.

Furthermore, the recursive cascading method enables the C-CGAN to outperform the R-CGAN even with limited training data, further demonstrating the practical value of C-CGAN. This study represents a preliminary exploration of modeling methods for optical communication systems, but several limitations remain to be addressed. Firstly, the current approach has deficiencies in model optimization. We have not performed fine-tuning of critical neural network parameters and network architecture, which limits the model’s precise modeling capability with small datasets. Secondly, regarding computational efficiency, we have not thoroughly investigated how to enhance the model’s computational performance through edge computing or distributed computing techniques. Finally, there is a lack of in-depth discussion on practical application scenarios for the proposed method. To address these issues, we plan to conduct follow-up research in the following aspects: Develop a hybrid modeling framework combining physical models with data-driven approaches, integrating the physical principles of optical systems to reduce reliance on large-scale training data and improve model generalizability. Explore the application of transfer learning and domain adaptation techniques to further reduce data requirements. Collaborate with industry partners to extend the model to complete optical fiber transmission systems or optical networks, validating the method’s effectiveness through practical deployment. Investigate the deep integration of deep learning algorithms with optical simulation technologies to build more accurate and efficient system simulation models. Extend this data-driven approach to broader optical communication systems to improve system performance and reduce design optimization costs.

Data availability

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from authors upon reasonable request by contacting Haifeng Yang at hifeng@bupt.edu.cn.

References

Zang, Y. et al. Multi-span long-haul fiber transmission model based on cascaded neural networks with multi-head attention mechanism. J. Lightw. Technol. 40, 6347–6358 (2022).

Agrawal, G. P. Nonlinear Fiber Optics (Academic Press, 2013).

Tao, Z. et al. Analytical intrachannel nonlinear models to predict the nonlinear noise waveform. J. Lightw. Technol. 33, 2111–2119 (2015).

Lasagni, C., Serena, P., Bononi, A. & Antona, J.-C. Generalized raman scattering model and its application to closed-form gn model expressions beyond the C+L band. In 2022 European Conference on Optical Communication (ECOC), 1–4 (2022).

Ye, G. et al. Impact of the input osnr on data-driven optical fiber channel modeling. J. Optical Commun. Network. 15, 78–86 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Convolutional neural network-aided dp-64 qam coherent optical communication systems. J. Lightw. Technol. 40, 2880–2889 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Deep learning based end-to-end visible light communication with an in-band channel modeling strategy. Opt. Express 30, 28905–28921 (2022).

Ye, H., Li, G. Y., Juang, B.-H. F. & Sivanesan, K. Channel agnostic end-to-end learning based communication systems with conditional GAN. In 2018 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), 1–5 (Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2018).

Wang, D. et al. Data-driven optical fiber channel modeling: A deep learning approach. J. Lightw. Technol. 38, 4730–4743 (2020).

You, X. et al. Low-complexity characterized-long-short-term-memory-aided channel modeling for optical fiber communications. Appl. Opt. 62, 8543–8551 (2023).

Yang, H. et al. Fast and accurate optical fiber channel modeling using generative adversarial network. J. Lightw. Technol. 39, 1322–1333 (2021).

Chu, J. et al. Fast and accurate optical fiber channel modeling using generative adversarial network. J. Lightw. Technol. 40, 1055–1063 (2022).

Wang, L., Gao, M., Zhang, Y., Cao, F. & Huang, H. Optical phase conjugation with complex-valued deep neural network for wdm 64-qam coherent optical systems. IEEE Photon. J. 13, 1–8 (2021).

Freire, P. J. et al. Complex-valued neural network design for mitigation of signal distortions in optical links. J. Lightw. Technol. 39, 1696–1705 (2021).

Ding, T. & Hirose, A. Online regularization of complex-valued neural networks for structure optimization in wireless-communication channel prediction. IEEE Access 8, 143706–143722 (2020).

Guberman, N. On complex valued convolutional neural networks (2016). arXiv:1602.09046.

Zhang, H. et al. An optical neural chip for implementing complex-valued neural network. Nat. Commun. 12 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Lei, Z., Zhou, M., Hasegawa, H. & Gao, S. Complex-valued convolutional gated recurrent neural network for ultrasound beamforming. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learning Syst. 36, 5668–5679 (2025).

Di Palo, E., Olm, J. M., D ria-Cerezo, A. & Bernardo, M. d. Sliding mode control-based synchronization of complex-valued neural networks. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 11, 1251–1261 (2024).

Derevyanko, S. The \((n+1)/2\) rule for dealiasing in the split-step fourier methods for \(n\)-wave interactions. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 20, 1929–1931 (2008).

Sinkin, O., Holzlohner, R., Zweck, J. & Menyuk, C. Optimization of the split-step fourier method in modeling optical-fiber communications systems. J. Lightw. Technol. 21, 61–68 (2003).

Srivastava, N., Hinton, G., Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Machine Learn. Res. 15, 1929–1958 (2014).

Trabelsi, C. et al. Deep complex networks (2017). arXiv:1705.09792.

Cui, B., Zhang, S., Su, J. & Cui, H. Fault diagnosis for inverter-fed motor drives using one dimensional complex-valued convolutional neural network. IEEE Access 12, 117678–117690 (2024).

Jin, J. et al. A complex-valued variant-parameter robust zeroing neural network model and its applications. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Topics Comput. Intell. 8, 1303–1321 (2024).

Lei, Z. et al. Fully complex-valued gated recurrent neural network for ultrasound imaging. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 35, 14918–14931 (2024).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 1026–1034 (Santiago, Chile, 2015).

Daneshfar, F. & Kabudian, S. J. Speech emotion recognition using a new hybrid quaternion-based echo state network-bilinear filter. In 2021 7th International Conference on Signal Processing and Intelligent Systems (ICSPIS), 1–5 (2021).

Daneshfar, F. & Kabudian, S. J. Speech emotion recognition system by quaternion nonlinear echo state network (2021). arXiv:2111.07234.

Smith, A. & Downey, J. A communication channel density estimating generative adversarial network. In 2019 IEEE Cognitive Communications for Aerospace Applications Workshop (CCAAW), 1–7 (Cleveland, OH, USA, 2019).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFB2900703) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62075014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haifeng Yang, Chao Li, Lu Han, Yongjun Wang, Qi Zhang, Xiangjun Xin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation. Haifeng Yang, Chao Li, Lu Han: Data validation, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing. Yongjun Wang, Qi Zhang, Xiangjun Xin: Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. Haifeng Yang analysed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, H., Wang, Y., Li, C. et al. A fiber channel modeling method based on complex neural networks. Sci Rep 15, 21552 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07595-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07595-1